Abstract

Background

In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), the association between cancer and cardioembolic or bleeding risk during oral anticoagulant therapy still remains unclear.

Purpose

We aimed to assess the impact of cancer present at baseline (CB) or diagnosed during follow-up (CFU) on bleeding events in patients treated with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for non-valvular AF (NVAF) compared with patients without CB or CFU, respectively.

Methods

All consecutive patients with NVAF treated with DOACs for stroke prevention were enrolled between January 2017 and March 2019. Primary outcomes were bleeding events or cardiovascular death, non-fatal stroke and non-fatal myocardial infarction, and the composite endpoint between patients with and without CB and between patients with and without CB.

Results

The study population comprised 1170 patients who were followed for a mean time of 21.6 ± 9.5 months. Overall, 81 patients (6.9%) were affected by CB, while 81 (6.9%) were diagnosed with CFU. Patients with CFU were associated with a higher risk of bleeding events and major bleeding compared with patients without CFU. Such an association was not observed between the CB and no CB populations. In multivariate analysis adjusted for anemia, age, creatinine, CB and CFU, CFU but not CB remained an independent predictor of overall and major bleeding (hazard ratio [HR] 2.67, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.8–3.89, p < 0.001; HR 3.02, 95% CI 1.6–3.81, p = 0.001, respectively).

Conclusion

During follow-up, newly diagnosed primitive or metastatic cancer in patients with NVAF taking DOACs is a strong predictor of major bleeding regardless of baseline hemorrhagic risk assessment. In contrast, such an association is not observed with malignancy at baseline. Appropriate diagnosis and treatment could therefore reduce the risk of cancer-related bleeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In patients with atrial fibrillation, the relationship between cancer and cardioembolic or bleeding risk during oral anticoagulant therapy is still unclear. |

During follow-up, newly diagnosed primitive or metastatic cancer is a strong predictor of major bleeding regardless of baseline hemorrhagic risk assessment. In contrast, such association is not observed with malignancy at baseline. |

A proper diagnosis and treatment could therefore decrease cancer-related bleeding risk. |

1 Introduction

Recent studies have demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between atrial fibrillation (AF) and cancer [1, 2]. Indeed, AF occurs more frequently in oncological patients, whereas a latent tumor is often unmasked in patients affected by AF treated with oral anticoagulants (OACs) [3].

The mechanisms underlying this association are multiple. First, cancer and AF share several risk factors [4] and improved outcomes and survival thanks to better treatments have led to an elderly oncological population more prone to developing cardiovascular diseases such as AF [5]. Furthermore, cancer itself induces a proinflammatory state that can trigger arrhythmic episodes [6, 7]. In fact, AF is frequently the first manifestation of a cardiac tumor [8,9,10], requiring a proper diagnostic work-up with echocardiography and second- to third-level imaging techniques to demonstrate the malignant behavior of the mass [11,12,13,14,15].

In addition, AF is a well-documented adverse effect of oncological surgery and several cytotoxic agents used in neoplastic patients [16].

The management of patients with cancer and concomitant AF is complex. In fact, in recently published guidelines [17], the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) enlightens how challenging it is to balance ischemic and hemorrhagic risk in neoplastic patients with AF. More precisely, these patients are at higher risk of ischemic and bleeding events due to the prothrombotic state and frailty induced by the neoplastic process [18, 19]. Moreover, conventional scores widely used to assess ischemic and hemorrhagic risk in AF patients (such as CHA2DS2-Vasc or HAS2-BLED, respectively) have not been adequately validated or studied in cancer patients [18].

For these reasons, oral anticoagulation raises several issues in these patients. Historically, anti-vitamin K antagonists (VKA) were the first OAC used in oncological AF patients, but some studies enlightened that international normalized ratio (INR) control was poor due to numerous pharmacological interactions with increased bleeding and ischemic risk [5]. More recently, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have shown to be promising in overcoming some concerns with respect to VKAs for these patients [20], but solid validations of the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs are still lacking. Furthermore, warnings have been issued regarding some potential drug interactions between antiblastic treatments and DOACs that may alter anticoagulant treatment [21]. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach involving both cardiologists and oncologists is necessary to tailor the best management, as cancer is a heterogeneous disease that requires different therapeutic approaches [18].

It should be noted that a higher bleeding risk should not prevent clinicians from starting anticoagulant therapy, as its benefits persist in these patients and modifiable hemorrhagic risk factors might be corrected [22]. For these reasons, it is currently unclear whether cancer diagnosed after initiation of the OAC carries the same hemorrhagic/prothrombotic risk compared with basal neoplasms, where the hemorrhagic risk may still be limited.

The aim of this study was to evaluate how malignant neoplasms influence ischemic and hemorrhagic events in patients with new-onset AF starting DOACs. In addition, we aimed to evaluate the potentially different bleeding risk of a basal malignancy and newly diagnosed malignancies during follow-up compared with patients without cancer present at baseline (CB) or diagnosed during follow-up (CFU), respectively.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design and Population

In this observational cohort study, we evaluated all consecutive patients who underwent clinical and instrumental evaluation for new-onset AF at the University Hospital Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy, between January 2017 and March 2019. Inclusion criteria were (1) patients with new-onset AF; and (2) patients treated with DOACs for stroke prevention in the setting of AF. Exclusion criteria were (1) patients receiving DOACs for indications other than AF; (2) patients receiving VKAs; (3) AF patients treated with VKAs for valvular AF; and (4) AF patients without an indication for anticoagulation according to ESC guidelines [22].

Data were collected as part of an approved protocol for the ‘PACE-AF’ observational prospective study. All patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [23] and provided informed consent for anonymous publication of scientific data. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

2.2 Data Collection, Risk Stratification and Outcomes

At baseline, home therapy, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities were assessed. For all patients, physical examination, electrocardiogram (EKG), laboratory tests, and a baseline cardiac ultrasound were performed. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anemia was defined as a hemoglobin (Hb) level < 12.0 g/dL in women and < 13.0 g/dL in men [24].

CHA2DS2-VASc, HAS-BLED, ATRIA, and ORBIT scores were used to assess ischemic and hemorrhagic risk at baseline. The choice of specific DOACs depended on the clinical judgment of the physician.

Cancer at baseline (CB) was defined as cancer occurring within 6 months prior to enrollment, any cancer treatment within the previous 6 months, or recurrent or metastatic cancer. Non-melanoma skin cancers were not included in this definition. Conversely, ‘previous cancer’ was defined as any other neoplastic medical history other than CB.

After enrollment, patients were followed up by outpatient visits or, if not possible, by telephone contacts. Cancer at follow-up (CFU) was defined as a newly diagnosed or recurrent malignant tumor or new metastases in patients with cancer at baseline during follow-up [25, 26]. Prespecified endpoints were bleeding events or cardiovascular death, non-fatal stroke and non-fatal myocardial infarction, and the composite endpoint (major adverse cardiovascular events [MACE]). Stroke was defined as an ischemic cerebral infarction caused by embolic or thrombotic occlusion of a major intracranial artery [27], while a diagnosis of myocardial infarction followed the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction [28].

Hemorrhagic events were classified according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) bleeding scale, i.e. major bleeding (MB) or minor bleeding [29]. MB was diagnosed if fatal or if causing a fall in Hb levels of 2 g/dL (1.24 mmol/L) or more, or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells. Minor bleedings were all non-MBs; these were further divided into clinically relevant and irrelevant. Clinically relevant bleeding did not meet the criteria for a major bleed but prompted a clinical response, in that it led to at least one of the following: a hospital admission for bleeding, physician-guided medical or surgical treatment for bleeding, or a change in antithrombotic therapy (including interruption or discontinuation of the study drug) [29].

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters and outcomes were compared between patients with and without CB or CFU. Continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean ± standard deviation (SD) according to values distribution evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test. To correlate continuous variables, the Mann–Whitney U test or Student’s t test were used where appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and compared between groups using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests when appropriate.

Multivariable Cox regressions with stepwise selection were performed to explore predictors of bleeding or ischemic events during follow-up using cancer at baseline, cancer diagnosed during follow-up (CFU), anemia, creatinine, age, and prior bleeding before enrolment as covariates. The probability for entry and removal from the model was p = 0.05 and p = 0.10, respectively.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All p values were two-sided and values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

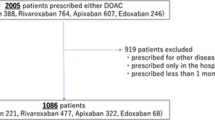

From January 2017 to March 2019, 1484 patients with new-onset non-valvular AF (NVAF) were enrolled in the PACE-AF Registry. As shown in Fig. 1 in the electronic supplementary material (ESM), patients already receiving OACs (78), those who had started VKAs (103), or those not treated with anticoagulation (133) were excluded. The final study population consisted of 1170 patients. During follow-up, 81 patients (6.9%) were diagnosed with cancer during follow-up (CFU cohort). The non-CFU cohort consisted of 1089 (93.1%) patients without a diagnosis of malignancy during the follow-up period. Gastrointestinal tumor was the most common malignancy in CFU patients (ESM Table 1 and ESM Fig. 2).

The description of the total population according to CB diagnosis and the characteristics of its subgroups are described in ESM Table 1 and ESM Table 2.

3.1 Patient Characteristics

The median age of the study population was 77 years and 51.8% were female. No significant differences regarding age, sex, risk factors, and AF pattern between the CFU and non-CFU cohorts were found (Table 1). Baseline ischemic and hemorrhagic risks as assessed using the CHA2DS2-VASc, and hemorrhagic risk scores (ATRIA, ORBIT, HAS-BLED and TIMI-AF) were similar between the two groups. The prevalence of other comorbidities was also similar between the two cohorts, whereas CFU patients more frequently showed active cancer at baseline (17% vs. 6.1%, p < 0.001).

Regarding the admission laboratory parameters, the CFU cohort had a higher white blood cell (WBC) count (9.9×10^9/L vs. 8.5×10^9/L, p = 0.029) [Table 1].

3.2 Bleeding and Ischemic Outcomes According to the Presence of Cancer

The mean follow-up time was 21.6 ± 9.5 months. The incidence of cardiovascular death, acute coronary syndrome, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), and the composite endpoint (MACE) was not different between the CFU and non-CFU cohorts (Table 2). Conversely, all bleeding events and MB occurred more frequently in CFU patients (p < 0.001 for both) [Table 2, Fig. 1]. As shown in ESM Table 3, the most common bleeding sites were the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract (32.3%), nose (24.2%), and urinary tract (15.1%).

Of the 39 bleeding events in the CFU population, 18 (46.2%) occurred in patients with upper and lower gastroenteric cancers and 6 (15.4%) in patients with urologic malignancies; the remaining bleeding events occurred in patients with breast cancer (7.6%), hematologic neoplasms (7.6%), gynecologic tumors (7.6%), brain tumors (7.6%), hepatocarcinoma (2.6%), melanoma (2.6%) or thyroid cancer (2.6%). Conversely, outcomes according to the presence of CB compared with patients without CB are described in ESM Table 4.

In a multivariable Cox regression model including CFU, CB, creatinine, anemia, age, and prior bleeding, CFU remained an independent predictor of overall bleeding (hazard ratio [HR] 2.67, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.8–3.89, p < 0.001) and MB (HR 3.02, 95% CI 1.6–3.81, p = 0.001), whereas CB was an independent predictor of overall bleeding (HR 2.02, 95% CI 1.21–3.39, p = 0.007), but not of MB (HR 1.73, 95% CI 0.73–4.41, p = 0.12) [Tables 3, 4]. Other independent predictors of MB were anemia at baseline (HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.343.81, p = 0.002), creatinine levels (HR 2.14, 95% CI 1.06–4.83, p = 0.03), and age (HR 1.03 95% CI 1.01–1.03, p = 0.033). Conversely, CB and CFU were not found to be predictors of ischemic events in contrast to the CHA2DS2-VASc score (ESM Table 5).

4 Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate ischemic and bleeding events in patients with new-onset AF treated with DOACs according to the presence of active cancer at baseline or a malignancy diagnosed during follow-up.

Our main findings were (1) CFU was associated with bleeding events during follow-up as compared with no CFU patients, but did not increase the ischemic risk; (2) basal active cancer was not strongly associated with an increased hemorrhagic burden as compared with CFU, as it did not result in an independent predictor of MB; and (3) DOACs seem to be effective in this troubled oncological population, as CFU and CB were not associated with a higher incidence of ischemic events.

4.1 Cancer and Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

Cancer is a well-recognized ischemic and bleeding risk modifier in the general population and shows a bi-univocal association with the onset of AF [30, 31]. Due to the paucity of data, there have been concerns regarding the use of the most common thromboembolic risk scores (CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc) in the initial assessment of patients with new-onset AF and concomitant malignancy. Moreover, data regarding the efficacy of oral anticoagulants in preventing embolic complications in this setting are scarce [18]. The ESC Guidelines for Cardio-Oncology [17] recommend the use of CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores (class IIa recommendation, level of evidence C) in cancer patients despite the lack of solid validation, prompting the tailoring of therapeutic decisions on the basis of the type of tumor, laboratory results (renal function, anemia) and clinical features. Some observational studies have confirmed the consistency of these scores in predicting ischemic events in patients with malignancy [32]. Our study corroborated these observations as the CHA2DS2-VASc score resulted in multivariate analysis, a strong, independent predictor of ischemic events during follow-up.

On the other hand, only a few studies, mainly retrospective or post hoc analyses of registry studies, have evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of DOACs in AF patients with cancer, with contrasting results [33,34,35]. More specifically, some registry studies demonstrated the substantial efficacy of DOACs in AF patients with cancer [33,34,35]. Accordingly, in our study cohort, neither CB nor CFU were associated with MACEs, acute coronary syndrome, and other ischemic events. However, clinicians are most concerned about bleeding complications in oncological patients taking oral anticoagulants: in the AMBER AF trial [36], it was observed that these patients were less likely to be treated with OACs for AF despite a significant ischemic risk, likely due to an often unwarranted evaluation of prohibitive bleeding burden. Furthermore, low-molecular-weight heparin was usually preferred over DOACs or warfarin in these patients [37].

Many studies have highlighted the additional bleeding risk associated with some malignancies in patients with cancer receiving anticoagulant therapy, whereas testicular cancer, non-melanoma skin cancer, and non-metastatic breast cancer were less likely to cause hemorrhages [38, 39]. Despite being a well-known modifier of hemorrhagic risk, cancer has only been included in the HEMORR2HAGES score among other bleeding risk scores [40]; however, it is not widely used in routine clinical practice due to the presence of features difficult to assess, such as genetic factors or the overall risk of falling.

A Spanish prospective study [36] demonstrated the efficacy of the commonly used hemorrhagic scores in predicting bleeding events in AF patients with breast cancer. Nevertheless, it must be noted that the overall bleeding burden associated with cancer might have been underrated in the cohort of this study due to the well-known low hemorrhagic risk associated with breast cancer without metastases.

Our study showed that patients with basal cancer are more frequently anemic, with an increased estimated bleeding risk assessed by HAS-BLED score compared with non-oncological patients.

However, despite resulting in an independent predictor of over-bleeding, the presence of active cancer before OAC initiation was not predictive of MB events during follow-up as compared with no CB patients. We assume that a prompt diagnosis, a more cadenced follow-up, and, obviously, proper treatment could potentially decrease the cancer-related hemorrhagic complications.

On the other hand, the development of new cancer at follow-up was associated with MB and non-MB despite similar hemorrhagic risks and Hb levels at baseline, resulting in an independent predictor of bleeding at multivariate analysis.

4.2 Types of Cancers and Bleeding Events

Our study outlined that different cancers carry different hemorrhagic burden, and pointed out that scores have only a modest predictive value in predicting bleeding events in these patients, especially when a new diagnosis of malignancy occurs during follow-up.

These previous observations have two important consequences. First, the presence of CB should not prevent clinicians from administering DOACs in cancer patients with AF despite higher HAS-BLED scores; however, since we observed that the CB population was, for obvious reasons, more prone to develop new cancer or metastases during follow-up, we strongly suggest that this population should be more strictly monitored during DOAC therapy, as their overall bleeding risk may change with the potential progression of the disease.

In addition, hemorrhagic risk assessment is a never-ending challenge for clinicians. When patients taking DOACs develop a new cancer or a new metastasis from a CB, cardiologists should assume that the overall bleeding risk has changed and should organize a proper follow-up to prevent hemorrhages (Fig. 2, Central Figure).

Central Figure. Ischemic and hemorrhagic events during follow-up in patients with AF treated with DOACs affected by CB or CFU compared with patients without CB or CFU, respectively. CB cancer present at baseline, CFU cancer diagnosed during follow-up, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, AF atrial fibrillation, DOACs direct oral anticoagulants

4.3 Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be addressed. First, the population of cancer patients is relatively small due to the low incidence of this disease in our cohort. Moreover, it was not possible to assess the bleeding risk with HEMORR2HAGES score because information such as the risk of falling or genetic factors was not available. Second, it is still not known whether proper antineoplastic therapy is able to reduce the prothrombotic and bleeding burden of malignancy. In fact, cancer offers an extremely wide range of clinical scenarios, which challenges any inferences or generalizations of study results.

5 Conclusions

Bleeding risk assessment is an ongoing challenge in patients with NVAF taking DOACs, especially with cancer. During follow-up, newly diagnosed primitive or metastatic cancer is a strong predictor of bleeding, especially major bleeding, regardless of the baseline hemorrhagic risk assessment. In contrast, such an association is not observed with malignancy at baseline. We hypothesize that appropriate diagnosis and oncologic treatment could therefore decrease cancer-related bleeding risk. Further studies are needed to evaluate the proper hemorrhagic risk assessment in these troubled populations.

References

Cheng W-L, Kao Y-H, Chen S-A, Chen Y-J. Pathophysiology of cancer therapy-provoked atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2016;219:186–94.

O’Neal WT, Lakoski SG, Qureshi W, et al. Relation between cancer and atrial fibrillation (from the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study). Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1090–4.

Farmakis D, Parissis J, Filippatos G. Insights into onco-cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:945–53.

Guzzetti S, Costantino G, Fundarò C. Systemic inflammation, atrial fibrillation, and cancer. Circulation. 2002;106(9):e40.

Russo AM. Anticoagulation in cancer patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. JACC CardioOncol. 2020;2:755–7.

Erichsen R, Christiansen CF, Frøslev T, Jacobsen J, Sørensen HT. Intravenous bisphosphonate therapy and atrial fibrillation/flutter risk in cancer patients: a nationwide cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:881–3.

Lateef N, Kapoor V, Ahsan MJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation and cancer; understanding the mysterious relationship through a systematic review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:127–32.

Foà A, Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, et al. Clues and pitfalls in the diagnostic approach to cardiac masses: are pseudo-tumours truly benign? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29:e102–4.

Angeli F, Bergamaschi L, Rinaldi A, et al. Sex-related disparities in cardiac masses: clinical features and outcomes. J Clin Med. 2023;12:2958.

Angeli F, Fabrizio M, Paolisso P, et al. Cardiac masses: classification, clinical features and diagnostic approach [in Italian]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2022;23:620–30.

Paolisso P, Foà A, Magnani I, et al. Development and validation of a diagnostic echocardiographic mass score in the approach to cardiac masses. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(11):2010–2.

Paolisso P, Foà A, Bergamaschi L, et al. Echocardiographic markers in the diagnosis of cardiac masses. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2023;36(5):464-473.e2.

D’Angelo EC, Paolisso P, Vitale G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac computed tomography and 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in cardiac masses. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2400–11.

Bedetti G, Pasanisi EM, Pizzi C, Turchetti G, Loré C. Economic analysis including long-term risks and costs of alternative diagnostic strategies to evaluate patients with chest pain. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008;6:21.

Bedetti G, Pizzi C, Gavaruzzi G, Lugaresi F, Cicognani A, Picano E. Suboptimal awareness of radiologic dose among patients undergoing cardiac stress scintigraphy. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:126–31.

Hajjar LA, Fonseca SMR, Machado TIV. Atrial fibrillation and cancer. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8: 590768.

Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS, et al. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4229–361.

Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, et al. 2016 ESC position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for practice guidelines: the task force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2768–801.

Fitzpatrick T, Carrier M, Le Gal G. Cancer, atrial fibrillation, and stroke. Thromb Res. 2017;155:101–5.

Russo V, Rago A, Papa A, et al. Use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients with malignancy: clinical practice experience in a single institution and literature review. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2018;44:370–6.

Steffel J, Collins R, Antz M, et al. 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. EP Eur. 2021;23:1612–76.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498.

Anon. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(2):2191–4.

McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:444.

Prins MH, Lensing AWA, Brighton TA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2014;1:e37–46.

Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:2187–91.

Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064–89.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J. 2019;40:237–69.

Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692–4.

Hu Y-F, Chen Y-J, Lin Y-J, Chen S-A. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:230–43.

Mery B, Guichard J-B, Guy J-B, et al. Atrial fibrillation in cancer patients: hindsight, insight and foresight. Int J Cardiol. 2017;240:196–202.

D’Souza M, Carlson N, Fosbøl E, et al. CHA2 DS2-VASc score and risk of thromboembolism and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation and recent cancer. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:651–8.

Laube ES, Yu A, Gupta D, et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and active cancer. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:213–7.

Fanola CL, Ruff CT, Murphy SA, et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban in patients with active malignancy and atrial fibrillation: analysis of the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7: e008987.

Melloni C, Dunning A, Granger CB, et al. Efficacy and safety of apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and a history of cancer: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Am J Med. 2017;130:1440-1448.e1.

Pardo Sanz A, Rincón LM, Guedes Ramallo P, et al. Current status of anticoagulation in patients with breast cancer and atrial fibrillation. Breast. 2019;46:163–9.

Pritchard ER, Murillo JR, Putney D, Hobaugh EC. Single-center, retrospective evaluation of safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular-weight heparin and vitamin K antagonist in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019;25:52–9.

Angelini DE, Radivoyevitch T, McCrae KR, Khorana AA. Bleeding incidence and risk factors among cancer patients treated with anticoagulation. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(7):780–5.

Johnstone C, Rich SE. Bleeding in cancer patients and its treatment: a review. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7:265–73.

Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J. 2006;151:713–9.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented at the 2021 Annual Scientific Sessions of the ESC and an abstract of this paper has been published in the European Heart Journal (Volume 42, Issue Supplement 1, October 2021, ehab724.0569, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.0569).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No external funding was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Francesco Angeli, Luca Bergamaschi, Matteo Armillotta, Angelo Sansonetti, Andrea Stefanizzi, Lisa Canton, Francesca Bodega, Nicole Suma, Sara Amicone, Damiano Fedele, Davide Bertolini, Andrea Impellizzeri, Francesco Pio Tattilo, Daniele Cavallo, Lorenzo Bartoli, Ornella Di Iuorio, Khrystyna Ryabenko, Marcello Casuso Alvarez, Virginia Marinelli, Claudio Asta, Mariachiara Ciarlantini, Giuseppe Pastore, Andrea Rinaldi, Daniela Paola Pomata, Ilaria Caldarera, and Carmine Pizzi declare they have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Authors' contributions

FA and LB contributed to the conception and design of this study. AR, LB, AS, MA, AS, SA, AI, NS, FB, DB, LC, DF, FPT, DC, KR, ODI, MC, MCA, CA, VM, GP and DPP organized the database and collected data. LB and FA performed the statistical analysis. FA and LB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IC and CP wrote sections of the manuscript. CP revised the article and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, and read and approved the submitted version.

Statement of guarantor

CP is the guarantor of this research and as such had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The study protocol received approval from the local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Indipendente dell’Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi). Data were collected as part of an approved observational study. The present study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All patients were informed about their participation in the registry and provided informed consent for the anonymous publication of scientific data.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Angeli, F., Bergamaschi, L., Armillotta, M. et al. Impact of Newly Diagnosed Cancer on Bleeding Events in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Treated with Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-024-00676-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-024-00676-y