Summary

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in significant upheaval in psychiatric care. Despite survey data collected from psychiatric patients and broad samples of individuals in single countries, there is little quantitative or qualitative data on changes to psychiatric care from the perspective of mental health providers themselves across developing countries.

Methods

To address this gap, we surveyed 27 practicing psychiatrists from Central and Eastern Europe, as well as Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

Results

Respondents observed a marked increase in anxiety in their patients, with increased (though less prominent) symptoms of depression, somatization, and addiction. They reported largescale changes in the structure of psychiatric treatment, chiefly a decline in psychiatric admissions and closing/repurposing of psychiatric beds. Results supported strong “buy in” from clinicians regarding the use of telehealth, though some clinicians perceived a reduction in the ability to connect with, and build alliances with, their patients. Finally, clinicians described an improvement in the image and meaning of psychiatry in society, increased awareness of mental illness, and greater value placed on mental health in the general population.

Conclusions

These changes warrant further empirical study as to their potential long-term ramifications, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic persists and new waves of infection occur periodically throughout the world. The increased psychiatric burden on the population coupled with the apparent salience of mental health and well-being in the public consciousness represents a global opportunity for psychiatry to advocate for further treatment, research, and education.

Zusammenfassung

Grundlagen

Die COVID-19-Pandemie hat zu erheblichen Umwälzungen in der psychiatrischen Versorgung geführt. Trotz Umfragedaten, die bei Psychiatriepatienten und breiten Stichproben von Individuen in einzelnen Ländern erhoben wurden, gibt es nur wenige quantitative oder qualitative Daten über Veränderungen in der psychiatrischen Versorgung aus der Perspektive der Anbieter psychischer Gesundheitsleistungen in Entwicklungsländern.

Methodik

Um diese Lücke zu schließen, befragten wir 27 praktizierende Psychiater aus Mittel- und Osteuropa sowie aus Afrika, dem Nahen Osten und Lateinamerika.

Ergebnisse

Die Befragten beobachteten bei ihren Patienten eine deutliche Zunahme von Angstzuständen und einen Anstieg (wenn auch weniger ausgeprägter) Symptome von Depressionen, Somatisierung und Suchtverhalten. Sie berichteten von weitreichenden Veränderungen in der Struktur der psychiatrischen Behandlung, vor allem von einem Rückgang der psychiatrischen Einweisungen und der Abschaffung/Neunutzung von psychiatrischen Betten. Die Ergebnisse belegen, dass die Kliniker den Einsatz von Telemedizin sehr befürworten, auch wenn einige von ihnen den Patientenkontakt und die Patientenbindung als beeinträchtigt empfanden. Schließlich beschrieben die Kliniker eine Verbesserung des Images und der Bedeutung der Psychiatrie in der Gesellschaft, ein größeres Bewusstsein für psychische Erkrankungen und einen höheren Stellenwert der psychischen Gesundheit in der Allgemeinbevölkerung.

Schlussfolgerungen

Diese Veränderungen bedürfen weiterer empirischer Untersuchungen im Hinblick auf ihre potenziellen langfristigen Auswirkungen, insbesondere da die COVID-19-Pandemie anhält und weltweit regelmäßig neue Infektionswellen auftreten. Die zunehmende psychiatrische Belastung der Bevölkerung in Verbindung mit der offensichtlichen Bedeutung der psychischen Gesundheit und des Wohlbefindens im öffentlichen Bewusstsein stellt eine globale Chance für die Psychiatrie dar, sich für weitere Therapien, Forschung und Aufklärung einzusetzen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic has resulted in significant upheaval in psychiatric care. Patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders have been reported to experience a worsening of symptoms [1], while those with new-onset psychiatric disorders also exhibit significant symptoms and poor coping [2]. There are reports of high levels of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and stress from diverse regions around the world including South Asia, the Middle East, Central and Eastern Europe, South America, and the United States [3,4,5,6]. During surges of COVID-19, some countries have reported a reduction in psychiatric emergency department visits [7] and inpatient admissions [8]. Emerging research indicates a change in the frequency of certain etiologies to psychiatric emergency departments during COVID-19 surges, with mood and affective disorders less commonly represented and an increase in psychotic disorders [8, 9].

Mental health providers working in the inpatient setting face changes to the nature and frequency of their workload, changes to inpatient care to mitigate infection risk [10], and increased fear of contracting COVID-19 [11]. In the outpatient setting, mental health providers have had to rapidly adopt and implement telehealth [12]. All these changes may affect mental health providers’ provision of care, stress, and coping. At the same time, there may be heightened appreciation for mental health providers and the importance of mental healthcare given the ubiquity of anxiety, uncertainty, and social isolation during the pandemic [13]. The impact of public health crises on medical providers has been documented in the previous coronavirus epidemics of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Those crises also resulted in significant psychological stress on providers, occupational changes to clinical practice including quarantine and other infection controls, and the use of novel technologies to facilitate safe communication [14,15,16]—though these effects were more regional compared to the global impact of COVID-19.

Despite many editorials on these topics as well as survey data collected from psychiatric patients and broad samples of individuals in specific countries, there is little quantitative or qualitative data on changes to psychiatric care from the perspective of mental health providers themselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most studies are from Western Europe and North America. An international perspective may help the field of psychiatry to understand common patterns and unique experiences, plan for future pandemics, develop programs to support mental health clinicians and their practices, and reimagine psychiatric care in a post-COVID-19 world. To address this gap in knowledge, we administered a survey to psychiatrists from Central and Eastern Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. Our goal was to explore mental health clinicians’ perspectives on COVID-19 changes to psychiatric care at the patient, treatment, provider, and societal levels.

Methods

Survey setting

The survey was administered to attendees at the Salzburg Weill Cornell Seminar in Psychiatry in Salzburg, Austria. The seminar is organized by a nonprofit organization, the Open Medical Institute, and is run in collaboration with Weill Cornell Medicine. The goal of the seminar is to provide medical education and mentoring to early career physicians from Central and Eastern Europe, as well as other non-Western countries around the world who typically do not have access to the same continuing education and clinical training opportunities available in Western, more developed nations.

Survey characteristics

The survey questions were developed by psychiatrists and psychologists and asked under four categories: (1) changes at the level of the patient (changes among outpatients and inpatients, and changes in anxiety, depression, somatization, addiction, and other symptoms); (2) changes at the structural level of treatment (change in treatment options); (3) changes at the level of the practitioner (challenges to colleagues, self-appraisal of coping, utility of telemedicine); and (4) changes at the societal level (change in image/meaning of psychiatry, change in awareness of mental health/illness, perceived societal readiness to adopt telemedicine). Respondents answered using 1–5 Likert-type scales. Open-ended questions were also asked related to which patients coped well vs. poorly, which changes to treatment were most and least effective, which group of staff members (e.g., nurses, physicians, psychologists) coped well and which poorly.

Survey respondents

Twenty-seven of the 29 attendees completed the survey (93% completion rate) prior to attending the seminar. Most respondents were attending physicians, many of whom held academic titles at university hospitals in their home country. The following countries were represented in the survey: Austria (2 fellows), Croatia (3 fellows), Belgium, Hungary, Czech Republic (2 fellows), Slovakia, Serbia, Latvia, Georgia, Lithuania, Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine (2 fellows), Moldova, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Qatar, Ethiopia, and Mexico (2 fellows). During the seminar week, and after submitting their individual surveys, fellows were cohorted into groups by geographic regions to discuss commonalities and differences in their experiences during the pandemic. These discussions were shared with the larger group in brief presentations.

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics (N [%]) and graphical inspection to explore quantitative responses to the survey. We extracted common narratives and themes that emerged from the open-ended responses to the survey. We also report narratives and themes that emerged from the group discussions. All data are reported in aggregate and are anonymized to protect the confidentiality of survey respondents. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

Changes at the level of the patient

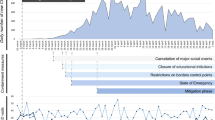

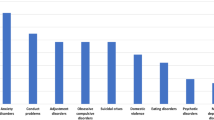

Most respondents reported a moderate to large change in psychiatric symptoms in both inpatients and outpatients, with a slightly larger percentage reporting changes in outpatients relative to inpatients (Fig. 1). Of the respondents, 58% reported that their patients experienced an increase in anxiety, most commonly a “significant” increase. Most respondents also reported that their patients experienced an increase in depression, though mild. Similarly, increases were reported in somatization, more often “mild”. Approximately half of survey respondents reported an increase in addiction symptoms. Among open-ended responses, respondents noted an exacerbation in symptoms in patients with pre-existing psychiatric illness, as well as an increase in patients presenting for psychiatric care for the first time. Also noted were relapses in patients with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, with some respondents commenting that the content of paranoid delusions was related to COVID-19. Several respondents noted increased suicidality in their patients. Patients with strong social support were noted to have coped well. In contrast, those patients who lacked social support, were elderly, or did not have a history of mental illness, coped poorly. Younger and more educated patients, as well as those with higher socioeconomic status, were reported to have fared better with telehealth.

Changes at the structural level of treatment

Many respondents noted a decrease in inpatient psychiatric beds and/or a reduction in admissions to hospitals (Fig. 2). Frequently reported was the repurposing of psychiatric beds and wards to COVID-19 treatment units. Several respondents noted a reduction or discontinuation of electroconvulsive therapy services. Most respondents described telehealth as one of the most effective changes to their practice; some noted that telemedicine was equivalent to face-to-face treatment, while others remarked that it was the “next best option” to in-person care. Respondents also remarked that both medication management and psychotherapy were effective via telehealth. Among changes to treatment that were less effective, survey respondents noted that the closing and repurposing of psychiatric beds/wards resulted in limited inpatient treatment options. Multiple respondents commented on the lack of group psychotherapy options. Despite the mostly positive comments regarding telehealth, respondents noted drawbacks as a lack of infrastructure and some patients who found telehealth to be less personal.

Challenges at the level of the practitioner

Most survey respondents endorsed “large challenges” for practitioners (Fig. 3). Challenges included an increase in demand for mental health services, a reduction in teamwork, practitioners’ own fears related to COVID-19, and redeployment. Many respondents noted that frontline workers and inpatient staff, particularly nurses, had difficulty coping with the challenges of the pandemic. Most respondents reported coping “adequately” to “very well” with the challenges of the pandemic; however, during the group discussions, survey respondents more openly acknowledged having challenges coping. Respondents described their own coping strategies as prioritizing work-life balance, engaging in hobbies, viewing new work assignments as opportunities to learn and grow, prioritizing credible and reliable scientific information, exercise, meditation, communicating with family/friends, and engaging in their own psychotherapy.

Changes at the societal level

Most survey respondents described a mild improvement in the image and meaning of psychiatry in society (Fig. 4). Many also noted a mild to large increase in awareness of mental health and mental illness in society. Respondents noted increased visibility of mental health professionals in the media, the ubiquity of anxiety/uncertainty in the general population, and the increase in new-onset psychiatric disorders as contributing to greater awareness and a reduction in stigma. Also noted was increased value placed on mental health and well-being among the general population. Survey respondents were more mixed on societal acceptance of telemedicine. A common concern was lack of access to a computer or cellphone, particularly in rural areas and among the elderly. Some remarked that telemedicine options may be better suited for outpatient services with established patients, as compared to acute settings. Reinforcement of avoidance in anxious patients was also a concern of using telemedicine. Some respondents noted concerns regarding regulations, legislation, and insurance coverage.

Discussion

We administered a survey to 27 practicing psychiatrists from Central and Eastern Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. The goal of the survey was to explore the perspectives of mental health providers on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected psychiatric care at the level of the patient, treatment setting, treatment, and society. The results demonstrated that this group of psychiatric providers reported significant changes to psychiatric care at each of these levels.

Clinicians observed a marked increase in anxiety in their patients, with increased (though less prominent) symptoms of depression, somatization, and addiction. This is consistent with epidemiologic findings that anxiety may be especially prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Survey respondents noted that those patients who had strong social support coped relatively well with their symptoms, while those without support, the elderly, and those with new-onset psychiatric symptoms coped poorly. These responses suggest that in times of global/public health upheaval, interventions and programs to enhance social support, particularly for the elderly, may be particularly fruitful. Responses also suggest that those with less “experience” in coping with mental health symptoms may fare worse when confronted with symptoms for the first time.

Concurrently, survey respondents reported largescale changes in the structure of psychiatric treatment, chiefly a decline in psychiatric admissions and closing/repurposing of psychiatric beds. The repurposing of inpatient psychiatric facilities reported across different countries—while perhaps unavoidable in times of surging infections—is concerning because of the potential for increased morbidity that may result for those with severe psychiatric illnesses who require inpatient care [18]. Patient hesitation to present to psychiatric facilities due to fear of infection may also be a factor in the decline in admissions [19]. Further research is warranted to determine the impact of such closing and repurposing to inform future decision-making, including how to best balance infection prevention/mitigation with continued inpatient care [20, 21]. This is critical given the significant demands on psychiatric emergency services during the pandemic [22].

The adoption of telehealth services for psychiatric patients, particularly in the outpatient setting, was described ubiquitously by our survey respondents. This finding dovetails with the rapid implementation of telehealth psychiatric clinics reported in the literature [23,24,25]. The widespread use of telehealth represents a transformative opportunity for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals to provide evidence-based care in efficient, safe, and low cost ways. The clinicians surveyed here had mostly positive feedback regarding the implementation of telehealth, indicating strong “buy in” from providers regarding the use of telehealth. Telehealth was not without its reported drawbacks, however, as some perceived a reduction in the ability to connect with, and build alliances with, their patients. It is notable that while commenting on its usefulness, our survey respondents acknowledged that they (and at times their patients) still preferred face-to-face clinical encounters. This may signal an opportunity for increasing training on therapeutic alliance-building in telehealth and for research into which patients do and do not benefit most from virtual care, particularly if hybrid options continue to be available in the future. Among additional challenges to telehealth that were elucidated, respondents also commented on the concern that some patients, particularly in rural areas and among the elderly, lack access to relevant infrastructure to engage in telehealth [26].

Our survey highlighted the challenges faced by mental health providers themselves and their frontline colleagues. Depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout, and suicide risk is well-documented amongst medical providers including psychiatrists [27, 28]. Interestingly, our survey respondents tended to answer questions about their coping as “adequate” or “very good”, yet when prompted in group-based discussions, acknowledged more challenges to coping. This observation is in line with earlier findings indicating paradoxical reluctance of physicians to seek help for their mental health problems [29]. These findings underscore the importance of programs targeted at the mental health and wellbeing of healthcare workers around the world that are at risk of various presentations of adjustment disorders, including burnout [30].

Respondents noted an increase in the meaning and awareness of psychiatry. They attributed this to increased visibility of mental health professionals in the media, the ubiquity of anxiety/uncertainty in the general population, and the increase in new-onset psychiatric disorders. Thus, one silver lining of the global pandemic may be that the shared and common sense of isolation and uncertainty has increased society’s own sense of vulnerability to, and empathy for, mental health disorders. It is notable that our multinational sample of respondents described this change across a diverse range of countries, as mental health stigma is a significant challenge and barrier to care around the world [31]. Findings suggest that the ongoing pandemic remains an opportunity for psychiatry to continue to advocate for mental health services, including educational, preventative, and treatment programs [13] to ensure equity in access to care.

Among limitations of our survey, it was given to a relatively small and selective group of psychiatric providers attending the seminar and may not be representative of the global psychiatric community nor specific country-level practices. Our sample size was too small and spread across many different countries to analyze and interpret country- or region-specific differences in survey responses. Nonetheless, we were able to extract themes and trends that have broad, cross-country implications for psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic and future public health crises on a multinational level. Although the survey was given prior to respondents attending the seminar, there may be response biases due to demand characteristics that influenced responses, particularly those related to questions that assessed respondents’ own coping with challenges.

Conclusion

We show that from an international perspective of psychiatric providers, there has been significant changes to psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic. These changes warrant further empirical study as to their potential long-term ramifications. The increased psychiatric burden on the population coupled with the apparent salience of mental health and well-being in the public consciousness represents a global opportunity for psychiatry to advocate for treatment, research, and education.

References

Gobbi S, Płomecka MB, Ashraf Z, Radziński P, Neckels R, Lazzeri S, et al. Worsening of preexisting psychiatric conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581426.

Pan KY, Kok AAL, Eikelenboom M, Horsfall M, Jörg F, Luteijn RA, et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: a longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:121–9.

Al Banna MH, Sayeed A, Kundu S, Christopher E, Hasan MT, Begum MR, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the adult population in Bangladesh: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Health Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2020.1802409.

Alkhamees AA, Alrashed SA, Alzunaydi AA, Almohimeed AS, Aljohani MS. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Compr Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152192.

Shukla A. Psychological impact of COVID-19 lockdown: an online survey from India: few concerns. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:591–2.

McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324:93–4.

Hoyer C, Ebert A, Szabo K, Platten M, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kranaster L. Decreased utilization of mental health emergency service during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271:377–9.

Abbas MJ, Kronenberg G, McBride M, Chari D, Alam F, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, et al. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on acute care mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:242–6.

Gonçalves-Pinho M, Mota P, Ribeiro J, Macedo S, Freitas A. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on psychiatric emergency department visits—A descriptive study. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92:621–31.

Brody BD, Shi Z, Shaffer C, Eden D, Wyka K, Parish SJ, et al. Universal COVID-19 testing and a three-space triage protocol is associated with a nine-fold decrease in possible nosocomial infections in an inpatient psychiatric facility. Psychiatry Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114036.

Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, Gearin P, Olcott W, Shankar V, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069.

Kanellopoulos D, Bueno Castellano C, McGlynn L, Gerber S, Francois D, Rosenblum L, et al. Implementation of telehealth services for inpatient psychiatric Covid-19 positive patients: A blueprint for adapting the milieu. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;68:113–4.

Marazziti D, Stahl SM. The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:261–261.

Lee S‑H, Juang Y‑Y, Su Y‑J, Lee H‑L, Lin Y‑H, Chao C‑C. Facing SARS: psychological impacts on SARS team nurses and psychiatric services in a Taiwan general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:352–8.

Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245–51.

Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A‑R, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–7.

Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:130–40.

Ono Y, Ono N, Kakamu T, Ishida T, Inoue S, Kotani J, et al. Impact of closure of the in-house psychiatric care unit on prehospital and emergency ward length of stay and disposition locations in patients who attempted suicide: a retrospective before-and-after cohort study at a community hospital in Japan. Medicine. 2021;100:e26252.

Shobassy A, Nordsletten AE, Ali A, Bozada KA, Malas NM, Hong V. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in a psychiatric emergency service: utilization patterns and patient perceptions. Am J Emerg Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.082.

Paletta A, Yu D, Li D, Sareen J. COVID-19 pandemic inpatient bed allocation planning—A Canada-wide approach. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;69:126–8.

Barnett B, Esper F, Foster CB. Keeping the wolf at bay: Infection prevention and control measures for inpatient psychiatric facilities in the time of COVID-19. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:51–3.

Ferrando SJ, Klepacz L, Lynch S, Shahar S, Dornbush R, Smiley A, et al. Psychiatric emergencies during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the suburban New York City area. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:552–9.

Sharma A, Sasser T, Schoenfelder Gonzalez E, Vander Stoep A, Myers K. Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the COVID-19 crisis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2020;30:404–13.

Sasangohar F, Bradshaw MR, Carlson MM, Flack JN, Fowler JC, Freeland D, et al. Adapting an outpatient psychiatric clinic to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a practice perspective. J Med Internet Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2196/22523.

Childs AW, Unger A, Li L. Rapid design and deployment of intensive outpatient, group-based psychiatric care using telehealth during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1420–4.

Rivera V, Aldridge MD, Ornstein K, Moody KA, Chun A. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to telehealth. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:44–5.

Denning M, Goh ET, Tan B, Kanneganti A, Almonte M, Scott A, et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–18.

Alkhamees AA, Assiri H, Alharbi HY, Nasser A, Alkhamees MA. Burnout and depression among psychiatry residents during COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19:1–9.

Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: a systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:567–76.

Kanellopoulos D, Solomonov N, Ritholtz S, Wilkins V, Goldman R, Schier M, et al. The CopeNYP program: A model for brief treatment of psychological distress among healthcare workers and hospital staff. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;73:24–9.

Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, Long JS. The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:853–60.

Funding

The authors did not receive any specific funding for this survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Jaywant, W. Aulitzky, J. Avari, A. Buchheim, M. Dubin, M. Galffy, M.A.S. Khoodoruth, G. Maytal, M. Skelin, B. Sperner-Unterweger, J.W. Barnhill and W.W. Fleischhacker declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Authors contributed equally and are listed alphabetically: W. Aulitzky, J. Avari, A. Buchheim, M. Dubin, M. Galffy, M.A.S. Khoodoruth, G. Maytal, M. Skelin and B. Sperner-Unterweger

Co-senior authors: J.W. Barnhill and W.W. Fleischhacker

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaywant, A., Aulitzky, W., Avari, J. et al. Multinational perspectives on changes to psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of practicing psychiatrists. Neuropsychiatr 37, 115–121 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-022-00452-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-022-00452-x