Abstract

Purpose of Review

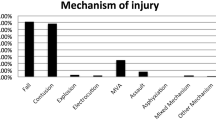

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant cause of morbidity and to a lesser extent mortality yearly. Dizziness remains a common complaint, presenting in up to 80% of patients post-head injury. This has obvious physical and psychological consequences not only to the individual but also a significant economic impact on society as a whole. Despite much being written in the field of TBI including concussion and sports-related head injury, the effects of trauma on the vestibular system have had relatively little study. Large-scale population studies addressing dizziness in the context of head injury do not exist in the literature. This article aims to provide an overview of dizziness post-TBI. The results from a large prospective database from the University Health Network (UHN) Workplace Insurance and Safety Board (WSIB) Neurotology are presented.

Recent Findings

The results of the UHN WSIB Neurotology database (n = 3438 head-injured workers) from the Canadian province of Ontario (1998–2014) either suggested or diagnosed BPPV in 23% post-head injured workers. One hundred and forty-nine workers (4.3%) were diagnosed with other distinct forms of peripheral vestibular dysfunction; the most common episodic type (35% of 149 workers) being a recurrent vestibulopathy (RV). The study did not find a causative link in the TBI patients studied to support a diagnosis for post-traumatic Meniere’s as the incidence of the disease in this cohort was equal to that in the general population.

Summary

This article is intended to provide an overview of post-traumatic dizziness following TBI, to discuss generally recognized inner ear disorders post-head injury, the results from the UHN WSIB Neurotology database and to address some of the controversies in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the 2016 US Veterans Administration/Department of Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Concussion-Mild Traumatic Brain Injury [2••], a TBI is defined as a traumatically induced structural injury and/or physiological disruption of brain function as a result of an external force and is indicated by new onset or worsening of at least one of the following clinical signs immediately following the event:

-

Any period of loss or a decreased level of consciousness

-

Any loss of memory for events immediately before or after the injury (post-traumatic amnesia)

-

Any alteration in mental state at the time of the injury (i.e. confusion, disorientation, slowed thinking, alteration of consciousness/mental state)

-

Neurological deficits (e.g. weakness, loss of balance, change in vision, praxis, paresis/plegia, sensory loss, aphasia) that may or may not be transient

-

Intracranial lesion

Numerous guidelines have been written on the inclusion criteria for diagnosis of a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Most concur that mTBI (while recognizing it as a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain) clinically is associated with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 13–15, resolution of post-traumatic amnesia within 24 h and a loss of consciousness for less than 30 min [3••].

-

Laboratory vestibular testing at UHN included ENG/VNG and combinations of vestibular evoked myogenic potential testing (both o and cVEMPs), vestibular head impulse testing (vHIT) and magnetic scleral search coil (MSSC) studies. Their incorporation in the formal test battery depended when the technology was available in our unit.

One should be careful when interchanging the word dizziness for vertigo and vice versa. By definition, all vertigo is considered dizziness but not all dizziness is considered vertigo—vertigo being largely confined to a feeling of hallucination/illusion of movement. In its episodic form, it would largely be considered to arise primarily from transient disruption of peripheral vestibular pathways and rarely from those central vestibular in origin.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •Of importance ••Of major importance

Editorial. The changing landscape of traumatic brain injury research. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(8):651.

•• Veterans Administration (VA)/Department of Defense (DoD) Clinical practice guideline for the management of concussion-mild traumatic brain injury. Version 2.0. 2016. The VA/DoD Guidelines present an excellent overview for the diagnosis, symptom presentation and management of individuals with concussions/mTBI’s.

•• Marshall S, Bayley M, McCullagh S, Velikonja D, et al. Updated clinical practice guidelines for concussion/mild traumatic brain injury and persistent symptoms. Brain Inj. 2015;29:688–700. The clinical practice guidelines for concussion/mTBI are extensive and recommendations have been made utilizing evidence medicine (EBM) levels where available.

Hoffer ME, Balough BJ, Gottshall KR. Post-traumatic balance disorders. Int Tinnitus J. 2007;13:69–72.

Maskell F, Chiarelli P, Isles R. Dizziness after traumatic brain injury: overview and measurement in the clinical setting. Brain Inj. 2006;20:293–305.

Schuknecht HF. Mechanism of inner ear injury from blows to the head. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1969;78:253–62.

Cho S-I, Gao SS, Xia A, Wang R, et al. Mechanisms of hearing loss after blast injury to the ear. PLoS One. 8:e67618.

•• Minor LB. Superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Am J Otol. 2000;21:9–19. The description of a new syndrome based on well-defined clinical and imaging findings represents a significant achievement in understanding the effects of a mobile third window involving the otic capsule.

Levenson MJ, Parisier S, Jacobs MD, et al. The large vestibular aqueduct syndrome in children. A review of 12 cases and the description of a new clinical entity. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:54–8.

Goodhill V, Ben H, Lecture S. Leaking labyrinth lesions, deafness, tinnitus and dizziness. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;2:99–106.

Cannon CR, Jahrsdoerfer RA. Temporal bone fractures. Review of 90 cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:285–8.

Ghorayeb BY, Yeakley JW. Temporal bone fractures: longitudinal or oblique? The case for oblique temporal bone fractures. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:129–34.

Diaz R, Brodie HA. Middle ear and temporal bone trauma. Cummings CW, Haughey BH, Thomas JR, Harker LA, Flint PW. Otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. 4th ed. Elsevier Mosby, 2005;4:2057–2079/139.

• Herdman SJ. Vestibular rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:96–101. This is an important article for understanding the concepts and treatment involved in vestibular rehabilitation therapy.

Johannsson M, Akerlund D, Larsen HC, Anderson G. Randomized controlled trial of vestibular rehabilitation combined with cognitive behavioural therapy for dizziness in older people. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:151–6.

Davies RA, Luxon LM. Dizziness following head injury: a neurotological study. J Neurol. 1995;242:222–30.

Hughes CA, Proctor L. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:607–13.

Ahn SK, Jeon SY, Kim JP, et al. Clinical charactersitics and treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2011;70:442–6.

Liu H. Presentation and outcome of post-traumatic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:803–6.

Kisilevsky V, Bailie NA, Dutt SN, Rutka JA. Lessons learned from the surgical management of benign paroxsymal positional vertigo: the university health network experience with posterior canal occlusion surgery (1988-2006). J Otolaryngol. 2009;2:212–21.

• Aron M, Lea J, Nakku D, Westerberg B. Symptom resolution rates of posttraumatic versus nontraumatic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:721–30. This paper discusses the clinical distinction between post-traumatic and non-traumatic BPPV, which is important for the reader to appreciate when treating these patients.

Campbell C, Cucci RA, Prasad S, Green GE, Edeal JB, et al. Pendred syndrome, DFNB4, and PDS/SLC26A4 identification of eight novel mutations and possible genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Mutat. 2001;2001:403–11.

Zhou G, Gopen Q, Poe DS. Clinical and diagnostic characterization of canal dehiscence syndrome: a great otologic mimicker. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:920–6.

Brantberg K, Bergenius J, Tribukait A. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in patients with dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Acta Otolaryngol(Stockh). 1999;119:633–40.

Shea JJ, Ge X, Orchik DJ. Traumatic endolymphatic hydrops. Am J Otol. 1995;16:235–40.

Pulec JL. Meniere’s disease: results of a two and one half year study of etiology, natural history and results of treatment. Laryngoscope. 1972;15:1703–15.

• Paparella MM, Mancini F. Trauma and Meniere’s syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1004–12. This often quoted paper has been used to support the link between auditory and physical trauma to the development of Meniere’s syndrome.

Schuknecht HF. Delayed endolymphatic hydrops. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1978;87:743–8.

Wolfson RJ, Leiberman A. Unilateral deafness with subsequent vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1975;85:1762–6.

Kamei T. Delayed vertigo. In: Hood JD, editor. Vestibular mechanisms in health and disease. London: Academic; 1978. p. 369–74.

Kudo Y, Futaki T. Fluctuant hearing loss in contralateral delayed endolymphatic hydrops. Equilibrium Res. 1987;46:297–303.

•• Ilan O, Syed MI, Aziza E, Pothier DD, Rutka JA. Olfactory and cochleovestibular dysfunction after head injury in the workplace: an updated series. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015; doi:10.1111/coa.12572. This paper presents the results of the UHN WSIB database and demonstrates the olfactory and cochleovestibular disturbance that patients can present with following head injury in the workplace.

Wuestoff C, Ilan O, Rutka JA. Neurological findings after electrical injury at the workplace. Laryngoscope. 2017; doi:10.1002/lary.26453.

Ogawa T, Rutka JA. Olfactory dysfunction in head injured workers. Acta Otolaryngology (Stockh). 1999;(Suppl 540):50–7.

Rutka J, Barber HO. Recurrent vestibulopathy—third review. J Otolaryngol. 1986;15:105–7.

Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Therapy in Meniere’s Disease. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Foundation Inc. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;11:181–5.

Marzo SJ, Leonetti JP, Raffin MJ, Letarte P. Diagnosis and management of post-traumatic vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1720–3.

Ernst A, Basta D, Seidl RO, Todt I, Scherer H, Clarke A. Management of posttraumatic vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:554–8.

Wladislavosky-Waserman P, Facer GW, Mokri B, Kurland LT. Meniere’s disease: a 30-year epidemiologic and clinical study in Rochester, Mn, 1951-1980. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1098–102.

Harris JP, Alexander TH. Current day prevalence of Meniere’s syndrome. Audiol Neurotol. 2010;15:318–22.

Bailey BJ, Vrabec JT. Victor Goodhill, MD, and perilymphatic fistula: reflecting on the man and the controversy. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(5):580–4.

Glasscock ME III, Hart MJ, Rosdeutscher JD, Bhansali SA. Traumatic perilymphatic fistula: how long can symptoms persist? A follow up report. Am J Otol. 1992;13:333–8.

Garg R, Djalilian HR. Intratypanic injection of autologous blood for traumatic perilymphatic fistulas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(2):294–5.

Hoffer ME, Gottshall KR, Moore R, Balough BJ, Wester D. Characterising and treating dizziness after mild head injury. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:135–8.

Rutka JA. In: Blitzer A, Jahn AF, editors. Evaluation of vertigo in office based surgery in otolaryngology. New York: Thieme; 1998. p. 71–8.

• Fife TD, Giza C. Post-traumatic vertigo and dizziness. Semin Neurol. 2013;33:238–43. This paper presents an excellent overview of vestibular dysfunction following head injury. Controversies associating trauma with vestibular migraine are analyzed.

Fotuhi M, Glaun B, Quan SY, Sofare T. Vestibular migraine: a critical review of treatment trials. J Neurol. 2009;256(5):711–6.

Bisdorff AR. Management of vestibular migraine. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4(3):183–91.

•• Brandt T, Bronstein AM. Cervical vertigo. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:8–12. This well written review of cervical vertigo is of critical importance in appreciating the controversies inherent in this often made diagnosis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Simon Carr and Dr. John Rutka declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Disclaimers

The UHN Research Ethics Board (REB) approved the analysis of study data presented under the Co-ordinated Approval Process for Clinical Research (14–8093).

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Otology: Vestibular Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carr, S., Rutka, J. Post-Traumatic Dizziness. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 5, 142–151 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-017-0154-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-017-0154-4