Abstract

Introduction

Patients are seeking greater involvement in their healthcare. It therefore may be beneficial to provide guidance on initial oral sumatriptan dose selection for the treatment of acute migraine in nontraditional settings, such as telehealth and other remote forms of medical care. We sought to determine whether clinical or demographic factors are predictive of oral sumatriptan dose preference.

Methods

This was a post hoc analysis of two clinical studies designed to determine preference for 25, 50, or 100 mg oral sumatriptan. Patients were aged 18–65 years with at least a 1 year history of migraine and experienced, on average, between one and six severe or moderately severe migraine attacks per month, with or without aura. Predictive factors were demographic measures, medical history, and migraine characteristics. Possibly predictive factors were identified using three analyses: classification and regression tree analysis, marginal significance (P < 0.1) within a full-model logistic regression, and/or selection within a forward-selection procedure in a logistic regression. A reduced model containing the variables identified in the preliminary analyses was developed. Due to differences in study design, data were not combined.

Results

A dose preference was expressed by 167 patients in Study 1 and 222 patients in Study 2. Gender and medical history of urologic and/or psychological conditions in Study 1 and duration of migraine history, height, and medical history of endocrine or neurologic disease and headache severity in Study 2 were identified as possibly predictive. The predictive model showed low positive predictive value (PPV; 23.8%) and low sensitivity (21.7%) for Study 1. For Study 2, the model showed moderate PPV (60.0%) but low sensitivity (10.9%).

Conclusions

No clinical or demographic characteristics alone or in combination were consistently or strongly associated with preference for oral sumatriptan dose level.

Trial Registration

The studies on which this paper is based were conducted before trial registration indexes were introduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although three different doses of oral sumatriptan for the treatment of acute migraine are available, there is no guidance regarding a particular starting dose. |

It may be beneficial to provide guidance on initial oral sumatriptan dose selection for the treatment of acute migraine in telehealth and other remote forms of medical care. |

The objective of this post hoc analysis was to determine whether clinical and demographic factors exist to guide initial dose selection of oral sumatriptan in the treatment of acute migraine. |

While most patients preferred an oral sumatriptan dose of 50 or 100 mg, this analysis did not identify predictors of oral sumatriptan dose preference. |

Guidance on oral sumatriptan dosing should be based on clinical trial data and previous treatment experience with antimigraine therapies. |

Introduction

Migraine is a common condition associated with moderate or severe headache that affects approximately 18% of women and 6% of men in the USA [1]. The burden of disease is reflected at not only the patient level, where symptoms can be debilitating [2], but also the societal level. A study using data from 2010 estimated that migraines lead to approximately 23 million outpatient and 908,000 emergency department visits each year in the USA, resulting in more than US$4 billion in healthcare costs [3]. Furthermore, an analysis of data from 2009 to 2017 showed that healthcare resource utilization by patients with migraine was 1.9 times higher than by patients without migraine [4].

There has been a trend in recent years for patients to seek greater involvement in their healthcare; as a result, they are looking for easier access to medical professionals and treatment [5]. The COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated the use of telehealth and similar remote healthcare services, which allows for rapid and convenient access to healthcare [6, 7]. Studies have shown that not only can healthcare professionals effectively deliver migraine treatment by telehealth, they are also comfortable doing so [8,9,10]. The recent emergence of on-demand digital health clinics (including those for migraine [11, 12]) has demonstrated this trend toward easier access to migraine treatment [13, 14]. In addition, self-care is available for a range of conditions via over-the-counter (OTC) medications, with a number of drugs having switched from prescription to OTC in the USA in recent decades, including diclofenac gel, fluticasone propionate, and omeprazole [15,16,17]. Triptans are available OTC in some European countries [18].

Oral sumatriptan (Imitrex; GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) for the treatment of acute migraine is available at three different dose levels in the USA (25, 50, and 100 mg) [19]. All three doses have been shown to be well tolerated and effective [20, 21], and level A evidence (medications recognized as effective based on clinical evidence) supports their use in the treatment of acute migraine [22]. Although three different doses are available, no guidance regarding a particular starting dose has been established. However, the US prescribing information advises that in patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment the maximum dose should be 50 mg [19]. The label states that a sumatriptan dose of 50 or 100 mg may provide greater efficacy than the 25 mg dose, but the 100 mg dose may not provide a greater effect than the 50 mg dose [19]. As a result, selection of the initial triptan dose for acute migraine is driven by prescribers based on their clinical experience and the individual experiences of the patient. Given the less personal nature of telehealth and digital health clinics, and the potential for OTC availability of triptans, determining whether there are characteristics that could aid in the selection of an initial dose could be of value.

One key aspect in the decision to select a specific treatment is patient preference, which may comprise multiple considerations. Efficacy, speed of response, formulation, tolerability, and cost are all key drivers of patient preference in treating migraine [23]. Most studies of patient preference to date, however, have focused on patients’ attitudes and wants, rather than specifics of drug treatment [23]. Therefore, it may be beneficial to provide guidance on initial oral sumatriptan dose selection for the treatment of acute migraine in nontraditional settings, such as telehealth and other remote forms of medical care, and to inform individuals who wish to participate in the decision-making process. The objective of this post hoc analysis of two clinical studies that addressed dose selection [24, 25] was to determine whether relevant clinical and demographic factors exist to guide initial dose selection of oral sumatriptan in the treatment of acute migraine.

Methods

Study Design

This was a post hoc analysis of two clinical studies of sumatriptan: these studies assessed patient preference for different doses of the drug [24, 25]. Patients in both studies were aged 18–65 years with at least a 1 year history of migraine and who were experiencing, on average, between one and six severe or moderately severe migraine attacks per month, with or without aura. The design and primary results of these studies have been published in detail previously and are summarized below. Both studies were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by relevant ethics and regulatory committees. The studies were conducted almost 30 years ago (i.e., 1994–1995) before clinical trial registries were initiated; therefore, trial registration numbers are not available. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study 1

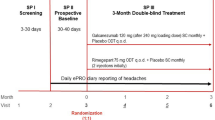

Study 1 was a multicenter, 6-month open-label study [24]. After receiving open-label oral sumatriptan 50 mg for their first three acute migraine headaches, patients were given the option of continuing the same dose, increasing the dose to 100 mg oral sumatriptan, or decreasing the dose to 25 mg oral sumatriptan (Fig. 1). After another three migraine headaches, patients could again change their dose by one dose interval. The primary endpoint for this study was patients’ acceptability of sumatriptan 50 mg, as indicated by their willingness to continue with that dose versus a desire to either increase the dose to 100 mg or decrease it to 25 mg.

Study 2

Study 2 was a multicenter, double-blind, 18-week randomized crossover study using a Latin square design [25]. Patients were provided blinded oral sumatriptan at a dose of 25, 50, or 100 mg in a random sequence for three consecutive migraine headaches (Fig. 2). The primary endpoint was the patients’ dose preference at the end of the study.

Statistics

For each study, data were evaluated separately using a newly defined binary outcome that reflected dose preference. In Study 1, the choice to decrease the oral sumatriptan dose to 25 mg during migraine attacks four through six was considered “lower,” and the choice to maintain the dose at 50 mg or increase it to 100 mg was considered “higher.” For the purpose of this analysis, patient choices in Study 1 are being used to describe patient preferences. Similarly, in Study 2, a preference for oral sumatriptan 25 mg was considered “lower,” and a preference for 50 or 100 mg was considered “higher.” The analysis did not attempt to distinguish between preference for oral sumatriptan 50 versus 100 mg.

Candidate predictive factors were demographic measures, medical history (e.g., endocrine or neurologic disease), and migraine characteristics (e.g., headache severity, headache frequency, duration of migraine history), each at baseline. Patients with incomplete baseline characteristic information were excluded from the models. Variables with < 3 occurrences were dropped from the model. A predictive model was built as the collection of factors identified among three separate analyses: classification and regression tree analysis [26], marginal significance (P < 0.1) within a full logistic regression model, and selection based on reducing the Akaike information criterion within a forward-selection procedure in a logistic regression model [27]. Finally, a reduced model containing the list of variables from these three different analyses was developed. This reduced model was then used to create a confusion matrix to illustrate the predictive properties of the model and assess its sensitivity and accuracy. Due to differences in the two study designs, data were not combined.

Populations are described with descriptive statistics. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.1.

Results

Patients

At completion of the two studies, 167 patients in Study 1 and 258 patients in Study 2 treated three migraine attacks and expressed a dose preference (Supplementary Material). Baseline characteristic information was incomplete for some patients (n = 36) in Study 2, resulting in a final study population of 222 (Table 1). The mean age of patients in Study 1 was 44.2 years and in Study 2 was 41.2 years, and the majority of patients were female (87.4% and 82.9% in Studies 1 and 2, respectively).

Dose Preference

Most patients preferred a higher sumatriptan dose of 50 or 100 mg. In Study 1, 50.9% (n = 85) elected to increase their sumatriptan dose to 100 mg, 13.8% (n = 23) reduced it to 25 mg, and 35.3% (n = 59) stayed on the 50 mg dose. In Study 2, 39.6% (n = 88), 35.6% (n = 79), and 24.8% (n = 55) preferred the 100, 50, and 25 mg doses, respectively.

Predictive Factors

In individual univariate models, there were no predictive factors strongly associated with dose preference. The few factors showing larger odds ratios each were medical history events with few observations, and no consistency was observed between the two studies (Fig. 3; Table 2). In Study 1, sex, urologic history, and psychological history were identified as possibly predictive but did not reach statistical significance in the selected model. The final predictive model showed accuracy of 79.6% but a low positive predictive value (23.8%) and low sensitivity (21.7%), illustrating the model’s inability to identify those with a preference for “lower” doses (Table 3). In Study 2, duration of migraine history, headache severity, height, and medical history of endocrine or neurologic disease were identified as possibly predictive. In the selected model, only a history of endocrine disease reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). The predictive model showed accuracy of 76.1% with a moderate positive predictive value (60.0%) but low sensitivity (10.9%), illustrating a high misclassification rate (40.0%) for those predicted to have a preference for “lower” doses (Table 3).

Standardized univariate logistic regression coefficients indicating factors possibly predictive of dose preference. *Including allergies. †Count refers to the number of “medical history condition body systems” for a subject. Absolute values of logistic regression coefficients do not necessarily correspond to statistical significance

Discussion

This comprehensive analysis of migraine- and non-migraine-related clinical factors, as well as demographic characteristics, in two clinical studies failed to identify predictors of oral sumatriptan dose preference. Although sex, urologic history, and psychological history were identified in Study 1 as possibly predictive of dose preference, they did not reach statistical significance. While sex as a predictive factor is plausible, there is no rationale for urologic and psychological history impacting dose preference; thus, these findings are likely anomalous. In Study 2, duration of migraine history, headache severity, height, and medical history of endocrine or neurologic disease were identified as possibly predictive, with history of endocrine disease being statistically significant. A relationship between some of the factors identified in Study 2 and migraine is possible. However, the lack of overlap between factors identified as possibly predictive between the two studies suggests that none are clinically important.

Previous analyses have found that only features of migraine itself, including headache severity at baseline, nausea, and photophobia/phonophobia, are predictive of 2 h response to triptans; numerous demographic and clinical variables have been found to be nonpredictive [28, 29]. Here, migraine-related baseline characteristics were not strongly associated with dose preference. Only duration of migraine history and headache severity were identified as possibly predictive of dose preference, but only in Study 2, and neither reached statistical significance. Consistent with studies of response to triptans [28, 29], no other clinical or demographic characteristics seem to have any impact on oral sumatriptan dose preference.

Overall, patients preferred a higher dose of oral sumatriptan of 50 or 100 mg rather than a lower 25 mg dose. In the original studies on which this analysis was based, better pain relief and faster pain relief were the primary reasons for preferring the higher doses, and poor tolerability was the main reason for decreasing the dose [24, 25]. In clinical trials, higher doses of sumatriptan have proven more effective than a lower 25 mg dose [30], but a 100 mg dose has not been shown to be more effective than the 50 mg dose [19]. However, sumatriptan 50 mg is associated with fewer adverse events than the 100 mg dose [30]. Altogether, these findings suggest that it would be difficult to offer specific guidance on initial sumatriptan dose selection. However, an initial trial of a moderate sumatriptan dose of 50 mg would be an appropriate starting point.

A strength of this analysis is that it was based on prospective, albeit historical, clinical studies designed to ascertain patient preference for sumatriptan dose [24, 25]. Because of the prospective nature of these studies, it was conceivable to test for a wide range of possible predictive factors using several statistical and machine-learning techniques. Importantly, the analysis has identified dose level as a potential key factor in treatment selection; this factor was omitted in previous analyses [23].

Several limitations of the study should be noted. Patients in Study 1 did not explicitly express a dose preference per se but, rather, elected to change or not change their dose to a lower or higher one. In addition, this was a post hoc analysis with limited statistical power. The sample size of patients who expressed a preference for the lower 25 mg dose of oral sumatriptan was small, limiting the ability to identify potential factors predictive of a preference for this lower dose. Populations in some patient groups, including male and non-White participants, were small, which could produce spurious findings. Furthermore, since the analysis was based on older studies, assessments of modern migraine metrics (e.g., Migraine Disability Assessment Test) were not captured. Although some of the predictive candidate factors derived from the original studies may have differed if the studies were conducted more recently, many of the factors remain relevant today (e.g., migraine characteristics and physical characteristics). Finally, the analysis did not differentiate between the 50 and 100 mg doses of oral sumatriptan, as their effectiveness may not be different [19, 30].

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to have attempted to predict factors associated with preference for different triptan doses. While most patients preferred a higher oral sumatriptan dose of 50 or 100 mg, no migraine-related clinical or demographic characteristics, alone or in combination, were consistently (across studies) or strongly (within studies) associated with preference for oral sumatriptan dose level. Guidance on sumatriptan dosing should be based on clinical trial data as well as previous treatment experience with antimigraine therapies.

References

Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia 1988;8(Suppl 7):1–96.

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1789–858.

Insinga RP, Ng-Mak DS, Hanson ME. Costs associated with outpatient, emergency room and inpatient care for migraine in the USA. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:1570–5.

Polson M, Williams TD, Speicher LC, Mwamburi M, Staats PS, Tenaglia AT. Concomitant medical conditions and total cost of care in patients with migraine: a real-world claims analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26:S3–7.

Calvillo J, Román I, Roa LM. How technology is empowering patients? A literature review. Health Expect. 2015;18:643–52.

Garfan S, Alamoodi AH, Zaidan BB, et al. Telehealth utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Comput Biol Med. 2021;138:104878.

Doraiswamy S, Abraham A, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e24087.

Szperka CL, Ailani J, Barmherzig R, et al. Migraine care in the era of COVID-19: clinical pearls and plea to insurers. Headache. 2020;60:833–42.

Minen MT, Szperka CL, Kaplan K, et al. Telehealth as a new care delivery model: the headache provider experience. Headache. 2021;61:1123–31.

Friedman DI, Rajan B, Seidmann A. A randomized trial of telemedicine for migraine management. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:1577–85.

Nurx. Headache and Migraine Treatment. Available at: https://www.nurx.com/headache-migraine-treatment/ (accessed January 17, 2023).

Cove. Diagnosis and treatment from the migraine experts. Available at: https://www.withcove.com/ (accessed January 17, 2023).

Jain T, Lu RJ, Mehrotra A. Prescriptions on demand: the growth of direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies. JAMA. 2019;322:925–6.

Bollmeier SG, Stevenson E, Finnegan P, Griggs SK. Direct to consumer telemedicine: is healthcare from home best? Mo Med. 2020;117:303–9.

Chang J, Lizer A, Patel I, Bhatia D, Tan X, Balkrishnan R. Prescription to over-the-counter switches in the United States. J Res Pharm Pract. 2016;5:149–54.

US Food and Drug Administration. Prescription to Over-the-Counter (OTC) Switch List. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/prescription-over-counter-otc-switch-list (Accessed January 17, 2023).

Over-the-counter omeprazole (Prilosec OTC). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2003;45:61–2.

Millier A, Cohen J, Toumi M. Economic impact of a triptan Rx-to-OTC switch in six EU countries. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84088.

Imitrex [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline, 2020.

Cutler N, Mushet GR, Davis R, Clements B, Whitcher L. Oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine: evaluation of three dosage strengths. Neurology. 1995;45:S5-9.

Sargent J, Kirchner JR, Davis R, Kirkhart B. Oral sumatriptan is effective and well tolerated for the acute treatment of migraine: results of a multicenter study. Neurology. 1995;45:S10–4.

Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3–20.

Xu X, Ji Q, Shen M. Patient preferences and values in decision making for migraines: a systematic literature review. Pain Res Manag. 2021;2021:9919773.

Dowson AJ, Ashford EA, Prendergast S, et al. Patient-selected dosing in a six-month open-label study evaluating oral sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine. Sumatriptan Tablets S2CM10 Study Group. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 1999;105:25–33.

Salonen R, Ashford EA, Gibbs M, Hassani H. Patient preference for oral sumatriptan 25 mg, 50 mg, or 100 mg in the acute treatment of migraine: a double-blind, randomized, crossover study. Sumatriptan Tablets S2CM11 Study Group. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 1999;105:16–24.

Breiman L, Friedman J, Olshen R, Stone C. Classification and Regression Trees. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1984.

Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2001.

Christoph-Diener H, Ferrari M, Mansbach H. Predicting the response to sumatriptan: the Sumatriptan Naratriptan Aggregate Patient Database. Neurology. 2004;63:520–4.

Diener HC, Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Almas M, Parsons B. Identification of negative predictors of pain-free response to triptans: analysis of the eletriptan database. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:35–40.

Pfaffenrath V, Cunin G, Sjonell G, Prendergast S. Efficacy and safety of sumatriptan tablets (25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg) in the acute treatment of migraine: defining the optimum doses of oral sumatriptan. Headache. 1998;38:184–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the original studies upon which this analysis is based.

Funding

This study, and the Open Access fee, were funded by Haleon (formerly GSK Consumer Healthcare).

Medical Writing

Medical writing assistance was provided by James Street, PhD of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by Haleon.

Author Contributions

Study design: Matt Fisher. Data analysis/interpretation: Matt Fisher, Abhay Aher, Mako Araga, Billy Franks. Critical revision and review of the manuscript: All authors. Project/data management: Matt Fisher, Abhay Aher. Statistical analyses: Billy Franks, Mako Araga. Approval of final draft for submission: All authors.

Prior Presentation

These data have previously been reported at the American Headache Society 64th Annual Scientific Meeting, Aurora, CO, June 9–12, 2022.

Author Disclosures

Abhay Aher, Mako Araga, and Matt Fisher: Former employees and current shareholders of GSK; current employees of Haleon. Billy Franks: Employee and shareholder of GSK.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

These studies were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by relevant ethics and regulatory committees. The studies were conducted almost 30 years ago (i.e., 1994–1995), before clinical trial registries were initiated; therefore, trial registration numbers are not available. All patients provided written informed consent.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fisher, M., Aher, A., Araga, M. et al. Patient Factors in the Dose Selection of Oral Sumatriptan for Acute Migraine: A Post Hoc Analysis of Two Randomized Controlled Studies. Pain Ther 12, 853–861 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00511-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00511-3