Abstract

Introduction

Migraine is a common disabling primary headache disorder characterized by attacks of severe pain, sometimes accompanied by symptoms including nausea and photo-/phono-phobia. Real-world data of patients with migraine who sufficiently (responders) and insufficiently (insufficient responders) respond to acute treatment (AT) are limited in China. This analysis explored whether responders to AT differ from insufficient responders in terms of clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and patient-reported outcomes in China.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme™, a point-in-time survey of internists/neurologists and their consulting patients with migraine, conducted in a real-world setting in China, January–June 2014. Responders and insufficient responders to prescribed AT were patients who typically achieved headache pain freedom within 2 h of AT in ≥ 4 and ≤ 3 of five migraine attacks, respectively. Responders were compared with insufficient responders; logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with insufficient response.

Results

Of 777 patients currently receiving AT, 44.0% were insufficient responders. Significantly fewer responders than insufficient responders had migraine with aura (13.1 vs. 23.8%; p = 0.0001). Responders reported a significantly lower mean Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) total score (5.5 vs. 6.6; p = 0.0325). Responders reported a lower mean impairment while working (50.0 vs. 63.9%; p < 0.0001), overall work impairment (52.6 vs. 66.0%; p < 0.0001), and activity impairment (48.9 vs. 59.0%; p < 0.0001). Statistically significant factors associated with insufficient response to AT included diabetes, unilateral pain, vomiting, sensitivity to smell, visual aura/sight disturbance, and an increase in MIDAS total score. However, there were no statistically significant differences in ATs received by responders and insufficient responders at any regimen of therapy.

Conclusions

Many patients with migraine in China are insufficient responders to AT, experiencing worse symptoms that lead to overall poorer quality of life than responders. This unmet need suggests that new effective treatment options are required for migraine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Migraine is estimated to be the fifth leading cause of years living with disability in China. |

Real-world data of patients with migraine who sufficiently (responders) and insufficiently (insufficient responders) respond to their acute treatment (AT) are limited in China, and cultural differences hinder the use of Western treatment patterns. |

This analysis explored whether responders to AT differ from insufficient responders in terms of clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and patient-reported outcomes in China. |

What was learned from the study? |

A considerable proportion of patients with migraine in China are insufficient responders to AT, experiencing worse symptoms that lead to overall poorer quality of life than their responding counterparts. |

Statistically significant factors associated with insufficient response to AT included diabetes, unilateral pain, vomiting, sensitivity to smell, visual aura/sight disturbance, and an increase in Migraine Disability Assessment total score. |

While there were clinical differences between responders and insufficient responders, there were no statistically significant differences in AT received by responders and insufficient responders at any therapy regimen, suggesting the need for new effective treatment options for migraine. |

Introduction

Migraine is a common and disabling primary headache disorder characterized by attacks of severe pain, which can be accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia [1].

In China, 482.7 million people were estimated to have headache disorders in 2017, and migraine is estimated to be the fifth leading cause of years living with disability [2]. With a population of over 1.3 billion people, China is considered to have the largest headache population worldwide; however, there are few epidemiological studies of headache burden, and those are limited by small sample sizes, are locality-specific, and have high rates of under-diagnosis and misdiagnosis [3].

Different from American and European guidelines, which recommend a stratified approach only, Chinese migraine treatment guidelines recommend a stratified and stepped approach to acute therapy (AT) [4, 5]. However, AT goals are similar in that they include pain freedom at 2 h post-dose [6] and alleviation of the patient’s most bothersome symptom [7]. Chinese guidelines for AT recommend non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), triptans, acetaminophen, and analgesics containing caffeine, while ergotamine derivatives, opioids, and barbiturates are not recommended for regular use [4, 5]. A retrospective analysis of data in the China Health Insurance Research Association (CHIRA) medical insurance claims database highlighted that NSAIDs were most frequently prescribed (68% of patients), with low use of migraine-specific triptans (3.3%) [5].

However, despite multiple AT choices, current therapies may be non-specific, ineffective, have cardiovascular contraindications, or be poorly tolerated [8]. This is evidenced in the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study where, of 2274 patients reporting at least one unmet need, 37.4% reported treatment dissatisfaction [9]. Further, the Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment survey reported that unmet needs related to the attack and inadequate treatment response were expressed by 89.5% and 74.1% of respondents, respectively [10]. Inadequate response to AT by patients was also reported by 34.3% of patients with migraine [11] in the US, and 42.2% of patients with migraine in Japan [12]. Additionally, inefficacy and poor tolerability can lead to compliance issues that can lead to medication delays and avoidance [13, 14]. Furthermore, poorly controlled headaches and regular misuse of acute antimigraine treatments can increase headache frequency and lead to chronic or medication overuse headaches (MOH) [15]. By acknowledging these limitations, there is a need for new treatments to control acute migraine.

The considerable data describing prescribing treatment patterns for migraine in American and Europe cannot be generalized to China due to cultural differences in diagnostic and treatment practices, prescription medication availability, and traditional Chinese medicine use [5]. Moreover, we do not know of any study investigating the insufficient response to migraine treatment and patient characteristics associated with the response among patients in China. This analysis of data collected in China explored whether patients with migraine who respond sufficiently (responders) to AT differ from patients who insufficiently respond (insufficient responders) in terms of clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and patient-reported outcomes, and identified those characteristics associated with insufficient response to treatment. Although the data were collected in 2014, it is still relevant, considering that the treatment paradigm has not changed and no new migraine treatments have since been approved in China.

Methods

Survey Design

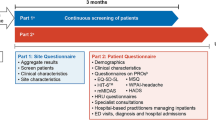

Data were drawn from the Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme (DSP)™, a multinational, point-in-time survey of internists and neurologists and their consulting patients with migraine, conducted in China, between January and June 2014. The DSP methodology has been previously published and validated [11, 16,17,18]. The survey comprised a physician survey, a physician-completed patient record form, and patient self-completion forms.

Participant Selection and Data Collection

Physicians were eligible to participate in the DSP survey if they had qualified between 1978 and 2008; were personally responsible for the management and treatment of patients with migraine, and had a clinical workload of at least 5 patients (for internists) or 10 patients (for neurologists) with migraine in a typical week. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of migraine.

Target physicians were identified using public lists of healthcare professionals, recruited by Adelphi local DSP fieldwork partners in China, and screened according to predefined selection criteria. A geographical sample of physicians involved in the management and treatment of patients with migraine, who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study, included the next 9 consecutively consulting patients with migraine meeting the patient eligibility criteria. For each patient who met the inclusion criteria, physicians completed a pen-and-paper patient record form with data extracted from patient medical records and, by using their judgement and diagnostic skills, as consistent with decisions made in routine clinical practice. The patient record form contained questions on patient demographics, clinical characteristics, treatment history, drivers of treatment choice, and general patient management.

Physicians then invited those patients for whom they completed a patient record form to complete a voluntary pen-and-paper patient self-completion form. The patient self-completion form collected data on demographics, symptoms, treatment, and level of disability using the Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) [19, 20] and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire [21].

Survey Measures

The MIDAS [19, 20] evaluates the level of disability due to headaches with higher values indicate greater migraine-related disability. Level of disability was determined numerically, where total scores (range 0–270) of 0–5 represent grade I: little/no disability; 6–10, grade II: mild disability; 11–20, grade III: moderate disability; 21–40, grade IV-A: severe disability; and ≥ 41, grade IV-B: very severe disability.

The WPAI [21] (disease-specific for headaches) measures headache-related time missed from work (absenteeism), impairment ineffectiveness at work (presenteeism), and overall work productivity loss (overall work impairment), and non-work-related activity impairment (total activity impairment). Higher values indicate more headache-related impairment, with WPAI component scores reported as percentage impairment.

Patients were asked, “On average, how many times out of 10 migraine attacks would you NOT use your acute treatment”, and of this answer how many of these instances are because they do not have their acute treatment with them i.e., total times not taken minus the number of times patients did not have medication with them.

Ethics and Consent

Using a checkbox, patients provided informed consent to take part in the survey. Data were collected in such a way that patients and physicians could not be identified directly. Data were aggregated before being shared with the subscriber and/or for publication.

Data collection was undertaken in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines [22] and as such did not require ethics committee approval. Each survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 [23], and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation [HIT] [24]. Fieldwork partners adhered to the national data collection regulations in China.

Data Analysis

Treatment response was determined based on a patient’s answer to the patient self-completion form question on AT: “In approximately how many migraine attacks would you say your prescription acute medicine stops the migraine pain entirely within 2 h of taking the medication?” Response options were 0 to 5 out of every five attacks. Based on their response, two patient groups were created: responders and insufficient responders (insufficient responders). Pain freedom at 2 h and consistency of response are recognized as important treatment goals in clinical guidelines [4]; thus, the definition of response to acute migraine treatment was based on pain freedom at 2 h and consistency of response above previously cited conservative estimates [11, 12, 25]. Responders were defined as patients with migraine who achieved pain freedom within 2 h of AT in ≥ 4 of five attacks and insufficient responders achieved pain freedom in ≤ 3 of five attacks [11, 12]. Patients who did not answer the question were excluded from the analysis.

Data were summarized using descriptive analyses. Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages were calculated for categorical variables.

This analysis compared patients who were insufficient responders with patients who were responders to current AT. The type of test used to compare the two groups (insufficient responders and responders) was dependent upon the type or distribution of the outcome variable. A t test was conducted for continuous variables, a Mann–Whitney U test was conducted for ordinal variables, and a chi-square/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. All statistical information was based on non-missing data.

Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds of a patient being a responder compared to being an insufficient responder. Covariates were initially chosen based on understanding of the disease (Supplementary Table S1). A logistic least absolute shrinkage operator (LASSO) regression [26] using cross-validation was then used on the selected covariates to identify those that were associated with responders and insufficient responders, indicated by a non-zero coefficient. Variables with a non-zero coefficient were then included as covariates in a logistic regression with the outcome responders vs. insufficient responders. An odds ratio of greater than 1 is associated with responders, and an odds ratio of less than 1 is associated with insufficient responders. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All analyses were generated using the statistical software package STATA® Version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 125 physicians (40 internists and 85 neurologists) provided data on 1125 patients. Of the 1125 patients, data were collected on 777 patients currently receiving AT for migraine of which 435 (56.0%) were responders and 342 (44.0%) were insufficient responders (Figs. 1 and 2). The majority of responders achieved pain freedom in four out of five migraine attacks (71.3%), while insufficient responders mostly achieved pain freedom in three out of five migraine attacks (78.4%).

Number of attacks that acute treatment provides pain freedom within 2 h (overall population with migraine). Responders were defined as patients with migraine who achieved pain freedom within 2 h of acute treatment in ≥ 4 of five attacks; insufficient responders (insufficient responders) achieved pain freedom in ≤ 3 of five attacks

Insufficient responders and responders had an overall mean age of 44.1 years and 54.2% were female. Most patients had never smoked (68.6%). Comorbidities were each reported by less than 10% of patients except hypertension (13.6%; responders 15.5 vs. insufficient responders 11.1%) and diabetes (9.0%; responders 6.7 vs. insufficient responders 12.0%). Significantly more responders lived with other family members (45.5 vs. 22.1%; p < 0.0001). More responders were in full-time employment than insufficient responders (responders 65.6 vs. insufficient responders 54.4%; p = 0.0019) (Table 1).

A diagnosis of migraine without aura was significantly more common for responders than insufficient responders (77.9 vs. 65.9%; p = 0.0002), while insufficient responders were more frequently diagnosed with migraine with aura (23.8 vs. 13.1%; p = 0.0001) (Table 1). There was no significant difference between responders and insufficient responders in the mean number of headache days per month over the last 6 months (3.4 vs. 3.2; p = 0.3044). MOH was statistically significantly less frequently among responders (1.1 vs. 7.3%; p = 0.0036) (Table 1).

The most prevalent symptom during a migraine attack was unilateral pain, reported for a significantly smaller proportion of responders vs. insufficient responders (72.9 vs. 79.8%; p = 0.028) (Table 2). Unilateral pain was also the most troublesome symptom for responders and insufficient responders (53.6 vs. 60.7%; p = 0.0481). Regarding symptoms during an attack, pain worsened by activity (responders 56.3 vs. insufficient responders 45.5%; p = 0.003) and light-headedness (41.6 vs. 29.3%; p = 0.0004) were more common among responders.

Of the 14 symptoms reported, there was a significant between-group difference in favor of responders in the severity (patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms) of unilateral pain, pain worsened by activity, nausea, and sensory aura (Supplementary Table S2). Overall, full control of symptoms was more likely to be achieved by responders. Responders (vs. insufficient responders) were over four times as likely to achieve full control of unilateral pain (responders 25.0 vs. insufficient responders 5.9%), over twice as likely to achieve full control of bilateral pain (31.0 vs. 13.8%) and pain worsened by activity (38.7 vs. 14.5%); and nearly twice as likely to achieve full control of sensory aura (43.0 vs. 23.4%), nausea (51.4 vs. 28.4%), and light headedness (52.0 vs. 29.4%) (Supplementary Table S2).

Treatment Patterns

Physician-Reported Treatment Classes and Products

NSAIDs including in combinations, specifically ibuprofen and diclofenac, were the current ATs in 73.5% of all patients. Approximately one-quarter of patients received either ergotamines and derivatives (18.2%) or triptans (8.9%), and 4.6% received non-opioid analgesics including combinations.

There were no statistically significant differences in the ATs (treatment class or product) received by responders and insufficient responders, at any regimen of therapy (Table 3; Supplementary Table S3).

Over 90% (94.4 vs. 93.2%) of responders and insufficient responders had one regimen of acute therapy, 5.4 vs. 6.5% had two regimens, and the remainder had ≥ 3 regimens of acute therapy. Any single treatment class combination was used by < 3% of either patient group (data not shown). NSAIDs including NSAIDs in combinations (74.2 vs. 76.1%), ergotamine and derivatives (16.4 vs. 15.9%), and triptans (9.8 vs. 7.1%) were the main regimen 1 AT classes used by responders and insufficient responders, respectively (Table 3). Ibuprofen and diclofenac were usually the AT product of choice at regimen 1, followed by ergotamine tartrate (Supplementary Table S3).

In response to the question “on average, how many times out of ten migraine attacks would you NOT use your acute treatment”, over half of responders (53.1%) had always taken their treatment in the last ten attacks (insufficient responders 32.3%). Treatment had not been taken ≥ 5 times in the last ten attacks by 1.4 and 6.5% of responders and insufficient responders, respectively.

Patient-Reported Burden of Migraine and its Treatment

A significantly smaller proportion of responders vs. insufficient responders did not suffer side effects of AT (50.0 vs. 65.9%; p < 0.0001) (Table 4). Stomach problems (nausea/vomiting) (25.4 vs. 13.2%; p < 0.0001) and dizziness (18.7 vs. 9.4%; p = 0.0003) were significantly more common in responders than insufficient responders and were generally the most bothersome. Thirst (12.9 vs. 5.0%; p = 0.0002) and dry mouth (10.4 vs. 4.1%; p = 0.001) were also more common in responders. The impact of side effects on patients’ lives was mostly mild, although the between-group difference was significant (p = 0.0461), with a greater proportion of responders considering that side effects did not impact their life (22. 6 vs. 11.2%) and insufficient responders reporting a moderate and severe impact (36.9 vs. 42.2%) (Table 4).

Compared with responders, overall patient disability and quality of life (QoL) was significantly worse for insufficient responders (Table 5). The mean MIDAS score was significantly higher for insufficient responders (responders 5.5 vs. insufficient responders 6.6; p = 0.0325). A smaller proportion of responders than insufficient responders reported severe/very severe disability (2.1 vs. 7.7%). While the WPAI mean percent work time missed due to migraine was similar between responders and insufficient responders (7.1 vs. 6.9%), compared with responders, insufficient responders reported greater mean impairments while working due to migraine (50.0 vs. 63.9%; p < 0.0001), mean overall work impairment due to migraine (52.6 vs. 66.0%; p < 0.0001), and activity impairment due to migraine (48.9 vs. 59.0%; p < 0.0001).

Factors Associated with Insufficient Response to AT

A total of 49 potential covariates were considered for the LASSO regression analysis, of which 20 variables, including age, triptans, sensitivity to smell, unilateral pain, and MIDAS, were used in the LASSO regression analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). Logistic regression analysis showed that significant factors associated with insufficient response to AT included: diabetes as a concomitant condition (odds ratio [OR]: 0.45; p = 0.035); the following migraine symptoms: unilateral pain (OR: 0.50; p = 0.012), vomiting (OR: 0.42; p = 0.007), sensitivity to smell (OR: 0.43; p = 0.044), and visual aura/sight disturbance (OR: 0.32; p = 0.004); and an increase in MIDAS total score (OR: 0.94; p = 0.001) and the WPAI percent activity impairment due to problem (OR: 0.99; p = 0.049) (Supplementary Figure S1). Significant factors associated with being a responder to AT included lives with other family (OR: 3.47; p < 0.001) and symptom light-headedness (OR: 2.23; p = 0.002).

Discussion

We evaluated approaches to the AT of migraine by physicians, identifying clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and patient-reported outcomes in patients who were responders and insufficient responders to AT in China. We found that, compared with responders, insufficient responders had different clinical characteristics, and carried a greater disease burden, yet were treated similarly by their physicians.

In this study, patient demographics were generally representative of the migraine population in China [5, 27]. Insufficient responders to AT comprised 44.0% of the study population, which is higher than the patient proportions (30–40%) reported in studies using a similar definition of insufficient response [11, 28]. Insufficient responders mainly had symptoms of moderate severity, and more commonly experienced migraine with aura, MOH, and unilateral pain than responders; responders had more mild symptoms, and more commonly experienced migraine without aura and bilateral pain. These characteristics differ from those in US patients with migraine, where migraine with aura is more common, particularly in responders, MOH is over twice as common, and bilateral pain is more often experienced by insufficient responders [11].

It is generally known that the migraine-related disability increases with headache frequency [29, 30]. The present data indicated that for responders and insufficient responders both the average number of headache days per month was very low (below 4) and that the reporting of disability by patients in terms of MIDAS grading was also low. The DSP methodology whereby physicians completed patient records forms for their next prospectively consulting patients, as well as the absence of quotas on patient type, means that the patient cohort is representative of the consulting population. Therefore, the majority of patients reporting little/no or mild disability in the MIDAS is in line with what would be expected from patients with a low frequency of migraine.

While the use of analgesics is justifiable for migraine, it is widely known that headache chronification occurs with their overuse [31]. In our study, MOH was significantly more likely to be reported by insufficient responders than responders. This may be due to treatment inefficacy, whereby insufficient responders do not receive pain relief on their current medication and therefore take their medication more frequently than recommended. Such medication overuse causes changes in pain processing networks, dependency networks and sensitization in patients with an underlying susceptibility for migraine progression [31].

Notably, more responders lived with another family member, which was found to be a significant indicator that a patient would respond to treatment. Better treatment effects could result from patients living with another family member who could provide social support and care. Indeed, patients with pain with supportive families reported significantly less pain intensity, greater activity levels, and tended to be working compared with patients with a non-supportive family [32].

This analysis found that migraine treatment patterns were overall similar between responders and insufficient responders, with NSAIDs, (mostly ibuprofen and diclofenac) most frequently prescribed currently. This similarity in treatment pattern may be because insufficient responders were not receiving an AT that could adequately manage their migraine attacks, indicating their unmet need. AT prescribing has also been reported to be similar between insufficient and sufficient responders to AT for migraine in Japan [12]. Current use of triptans did not significantly differ between the groups. Also reflecting their unmet treatment need, insufficient responders had poorer adherence to treatment during a migraine attack than responders.

Despite some consistency of the recommended treatments with American and European guidelines, treatment patterns in China generally differed from those in the US [11]. Data retrieved from the CHIRA outpatient database in 2016/2017 found that 26.4% of patients were prescribed acute medication. Similar to our findings, 68.8% of patients received non-aspirin NSAIDs (mostly ibuprofen), 7.1% opioids, 6.1% ergotamines, and 3.3% of patients received triptans [5]. The common prescribing of NSAIDs as acute medications may reflect their accessibility and relatively low cost. The notable low triptan use among Chinese patients contrasts with the high use in the US (> 80%) [11] and in Japan (> 75%) [12, 33]. The low rate of triptan use in China may be due to limited triptan availability in many hospitals and pharmacies resulting in barriers to access [5]. It may also be explained by their high price limiting their widespread use [5, 34]. Furthermore, compared with the seven types of triptans and their different forms in the US, the choice of triptans is small in China, with only three triptan types commercially available (sumatriptan, zolmitriptan, and rizatriptan) [5]. Triptan under-use may be through patient choice, with most patients unable to afford the high cost of each triptan tablet.

In contrast with the US [11, 35], the low opioid use in our study reflects the overall low opioid use in China due to government regulations [5]. While effective pain relief and guidelines may predominate in the physicians’ treatment decision, factors associated with patient choice and medication use, such as cost, availability of medicine and tradition (i.e., a culture’s customs, ideas and beliefs), are also important because these factors could influence the treatment decision.

Overall, the majority of patients in the US take their medicine at the first sign of a migraine attack [11] while patients in China wait until or even after the pain starts. Such behavior may suggest culture differences. A US study found that patients taking medication for a migraine attack when the pain starts were significantly (p < 0.001) more likely to be insufficient responders than those taking their medication at the first sign of a migraine attack (i.e., during the premonitory phase) [11]. This was not found in our Chinese study. The majority of patients in both groups waited for the pain to start before taking their medication. A possible reason for this difference may be the greater use of triptans in the US (82.8%) [11], which provide greater efficacy when taken while migraine pain is still mild [36].

While this analysis showed that a significantly greater proportion of insufficient responders vs. responders did not experience side effects of AT, the impact of side effects on insufficient responders’ lives was greater than that on responders. Generally, differentiating between treatment-related adverse events and migraine symptoms can be difficult, particularly when the event could be either, such as in the cases of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. Thus, a moderate and severe impact on insufficient responders’ lives could be due to migraine symptoms while the lack of impact on responders’ lives could be due to treatment efficacy. On the other hand, a high response rate generally indicates that the drug is effective and thus might cause side effects. Furthermore, it is reasonable to associate a lower rate of side effects with reduced effectiveness, since some migraine symptoms like vomiting might result in decreased drug absorption, which in turn may contribute to reduced efficacy and fewer side effects.

Several studies have shown that migraine negatively affects QoL [37]. Insufficient responders experienced more severe symptoms, greater disease burden, worse QoL, and greater impairments in work productivity and activities versus responders. Corresponding with our findings, more severe workplace problems has been associated with a higher disability level in patients with migraine [38], and people with migraine generally continue to work despite symptoms, with considerable productivity loss due to presenteeism [39]. In contrast to our analysis of Chinese patients, data from the US Adelphi Migraine DSP found that patients with migraine report worse disability (MIDAS; insufficient responders only), with proportionally more insufficient responders with moderate or severe disability but a lower impact of headache on work (WPAI; responders and insufficient responders) [11]. However, patients in China reported worse disability, with proportionally more with mild or moderate disability, and worse impairment while working, overall productivity, and activity, compared to patients in Japan [12]. These findings may also be due to cultural differences between Asian and Western societies in dealing with illness.

Based on bivariate analyses, among the multiple comparisons, Chinese patients who were insufficient responders achieved pain freedom within 2 h in ≤ 3 of five attacks, experienced migraine with aura, had unilateral pain as a symptom of an attack and as a most troublesome symptom, sensitivity to smell as a symptom of an attack, more moderate symptoms, gained partial symptom control, and reported greater side-effect impact. After consideration of the variables identified by LASSO, these multivariate analyses confirmed that Chinese patients who were insufficient responders were significantly more likely than responders to have diabetes, unilateral pain, vomiting, sensitivity to smell, visual aura/sight disturbance, and worse disability (increase in MIDAS total score).

Despite the association of migraine with several comorbidities and metabolic/endocrine disorders, including insulin-related factors, the relationship between migraine and type 2 diabetes mellitus remains unclear due to relatively few existing studies and conflicting results [40, 41]. Several mechanisms have been suggested for an inverse relationship between migraine and diabetes [41], including lifestyle, environmental, and genetic factors, since migraine can be triggered by such factors; the actions of biochemical biomarkers relevant to migraine pathophysiology (e.g., proinflammatory cytokines and neuropeptides); and the autonomic nervous system since it influences the metabolic changes that occur. However, the role of diabetes in the protection against migraine attacks remains uncertain [41].

The LASSO procedure is a regularization method that supports simple models with fewer parameters. It is useful in cases with limited evidence because it enables the testing of many potentially correlated factors and identifies those most important. The present outcomes reflect the relative strength of the factors in each model, but they do not suggest clinical meaningfulness, and they ignore nonsignificant variables that may otherwise be important.

The AMPP study identified a different set of significant predictors of inadequate treatment response to those in our analysis, [42], and subsequently found yet a different set of predictors [11]. A high MIDAS total score (severe disability) was the only predictor found to be similar among those identified in our analysis of Chinese patients. Factors identified in our analysis also differ from those found in the Japan Adelphi Migraine DSP population [12]. Such differences between real-world studies are likely due to varying patient characteristics, behaviors, and individual treatments, and time of data capture.

While outside the scope of this manuscript, future research in the differences in response patterns between patients with aura and those without in China and elsewhere would be valuable.

The point-in-time design of the DSP prevents any conclusions about causal relationships, although identification of statistically significant associations is possible. It therefore cannot be determined if the patient characteristics caused the insufficient response to AT or vice versa. Physicians were selected based on the number of patients with migraine seen; therefore, the physicians were experienced with treating migraine and their patient load and standard of care may not reflect those of more general practitioners. Generalization of the findings to all patients with migraine may also be limited as the analysis may represent the patient burden and outcomes of patients who visit their physicians and who may be more severely affected by migraine than patients who do not consult their physician as frequently. Despite such limitations, this collection of real-world data enabled evaluation of typical variations in AT prescribing patterns, migraine-related symptoms and burden, and satisfaction with AT.

A strength of this study is that it uses real-world data collected from the Adelphi Migraine DSP that uses standardized methodology and is well validated. Nevertheless, our findings should be considered with regard to the limitations of the DSP survey. While the data were collected several years ago (2014), they are still relevant considering that the treatment paradigm has not changed and no new migraine treatments have since been approved in China. However, data were collected over a relatively short time period (6 months), which may have influenced the findings.

Conclusions

This study showed that a considerable proportion of patients with migraine in China have an insufficient response to their AT. Compared with responders, insufficient responders reported significantly greater disability and impairment in work productivity. Insufficient responders were less likely to achieve full symptom control, more likely to be non-adherent to treatment, and experience worse symptoms, which lead to an overall poorer QoL than their responding counterparts. Significant factors associated with insufficient response to AT included diabetes, unilateral pain, vomiting, sensitivity to smell, visual aura/sight disturbance, and an increase in MIDAS total score, while response to AT was associated with living with another family member and light-headedness. This study highlights the unmet needs of patients with migraine in China and, while these might partly be addressed by more effective use of current ATs, it demonstrates the requirement for new effective treatment options for migraine.

References

Eigenbrodt AK, Ashina H, Khan S, et al. Diagnosis and management of migraine in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(8):501–14.

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59.

Yao C, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. Burden of headache disorders in China, 1990–2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):102.

Chinese Medical Association Group. Guide to the prevention and treatment of migraine in China [Chinese]. Chin J Pain Med. 2016;22:721–7.

Yu S, Zhang Y, Yao Y, Cao H. Migraine treatment and healthcare costs: retrospective analysis of the China Health Insurance Research Association (CHIRA) database. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):53.

Diener HC, Tassorelli C, Dodick DW, et al. Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of acute treatment of migraine attacks in adults: fourth edition. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(6):687–710.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Migraine: Developing Drugs for Acute Treatment Guidance for Industry February 2018. Clinical/Medical. https://www.fda.gov/media/89829/download. Accessed 22 November 2022.

Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Targeted CGRP small molecule antagonists for acute migraine therapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(2):304–12.

Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53(8):1300–11.

Lipton RB, Munjal S, Buse DC, et al. Unmet acute treatment needs from the 2017 Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment study. Headache. 2019;59(8):1310–23.

Lombard L, Ye W, Nichols R, et al. A real-world analysis of patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and level of impairment in patients with migraine who are insufficient responders vs. responders to acute treatment. Headache. 2020;60(7):1325–39.

Hirata K, Ueda K, Ye W, et al. Factors associated with insufficient response to acute treatment of migraine in Japan: analysis of real-world data from the Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):274.

Tajti J, Majláth Z, Szok D, Csáti A, Vécsei L. Drug safety in acute migraine treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(6):891–909.

Gallagher RM, Kunkel R. Migraine medication attributes important for patient compliance: concerns about side effects may delay treatment. Headache. 2003;43(1):36–43.

Diener HC, Dodick D, Evers S, et al. Pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of medication overuse headache. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(9):891–902.

Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-specific programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–72.

Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, Milligan G, Piercy J. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the disease specific programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8): e010352.

Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371–80.

Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Sawyer J. Reliability of the migraine disability assessment score in a population-based sample of headache sufferers. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:107–14.

Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(Suppl. 1):S20–8.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65.

European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) Code of Conduct. Updated September 2021. https://www.ephmra.org/code-conduct-aer. Accessed 22 November 2022.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule; 2003. http://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf. Accessed 22 November 2022.

Health Information Technology. Health Information Technology Act. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf. Accessed 22 November 2022.

Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Dayno JM. What do patients with migraine want from acute migraine treatment? Headache. 2002;42(Suppl 1):3–9.

Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J Royal Statist Soc B. 1996;58(1):267–88.

Liu R, Yu S, He M, et al. Health-care utilization for primary headache disorders in China: a population-based door-to-door survey. J Headache Pain. 2013;14(1):47.

Viana M, Genazzani AA, Terrazzino S, Nappi G, Goadsby PJ. Triptan nonresponders: do they exist and who are they? Cephalalgia. 2013;33(11):891–6.

Irimia P, Garrido-Cumbrera M, Santos-Lasaosa S, et al. Impact of monthly headache days on anxiety, depression and disability in migraine patients: results from the Spanish Atlas. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8286.

Ishii R, Schwedt TJ, Dumkrieger G, et al. Chronic versus episodic migraine: the 15-day threshold does not adequately reflect substantial differences in disability across the full spectrum of headache frequency. Headache. 2021;61(7):992–1003.

Vandenbussche N, Laterza D, Lisicki M, et al. Medication-overuse headache: a widely recognized entity amidst ongoing debate. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):50.

Jamison RN, Virts KL. The influence of family support on chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(4):283–7.

Meyers JL, Davis KL, Lenz RA, Sakai F, Xue F. Treatment patterns and characteristics of patients with migraine in Japan: a retrospective analysis of health insurance claims data. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(12):1518–34.

Luo N, Qi W, Zhuang C, et al. A satisfaction survey of current medicines used for migraine therapy in China: is Chinese patent medicine effective compared with Western medicine for the acute treatment of migraine? Pain Med. 2014;15(2):320–8.

Lipton RB, Buse DC, Friedman BW, et al. Characterizing opioid use in a US population with migraine: results from the CaMEO study. Neurology. 2020;95(5):e457–68.

Goadsby PJ, Zanchin G, Geraud G, et al. Early vs. non-early intervention in acute migraine-’Act when Mild (AwM).’ A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of almotriptan. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(4):383–91.

Taşkapilioğlu Ö, Karli N. Assessment of quality of life in migraine. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2013;50(Suppl 1):S60–4.

D’Amico D, Grazzi L, Curone M, et al. Difficulties in work activities and the pervasive effect over disability in patients with episodic and chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(Suppl 1):9–11.

de Dhaem OB, Sakai F. Migraine in the workplace. eNeurologicalSci. 2022;27: 100408.

Fagherazzi G, El Fatouhi D, Fournier A, et al. Associations between migraine and type 2 diabetes in women: findings from the E3N Cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(3):257–63.

Rivera-Mancilla E, Al-Hassany L, Villalón CM, Van Den Maassen Brink A. Metabolic aspects of migraine: association with obesity and diabetes mellitus. Front Neurol. 2021;12:686398.

Lipton RB, Munjal S, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Bennett A, Reed ML. Predicting inadequate response to acute migraine medication: results from the American migraine prevalence and prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2016;56(10):1635–48.

Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, et al. Good publication practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):461–4.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Real World Migraine DSP. Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection. The analysis described here used data from the Adelphi Real World Migraine DSP. The DSP is a wholly owned Adelphi Real World product. Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis is one of multiple subscribers to the DSP. Publication of survey results was not contingent on the subscriber’s approval or censorship of the publication. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Sue Libretto, PhD, of Sue Libretto Publications Consultant Ltd, on behalf of Adelphi Real World in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines [43].

Author Contributions

Lei Zhang was responsible for clinical oversight and guidance as lead author. All authors were involved in (1) conception or design, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting and revising the article; (3) providing intellectual content of critical importance to the work described; and (4) final approval of the version to be published, and therefore meet the criteria for authorship in accordance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

This work has been previously presented as a poster at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Europe 2022 in Vienna, Austria, between the 6-9th November 2022.

Disclosures

Lei Zhang, Diego Novick, Shiying Zhong and Jinnan Li are employees of Eli Lilly and Company and have stocks/shares in Eli Lilly and Company. Chloe Walker, Lewis Harrison, James Jackson, Sophie Barlow, and Sarah Cotton are employees of Adelphi Real World.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Physicians and patients provided consent to participate before contributing to the survey. Responses were anonymized before aggregated reporting. A survey number was assigned to all participating physicians and patients to enable anonymous data collection, and data linkage during data collection and analysis, enabling physician–patient data matching.

Using a checkbox, patients provided informed consent to take part in the survey. Data were collected in such a way that patients and physicians could not be identified directly. Data were aggregated before being shared with the subscriber and/or for publication.

Data collection was undertaken in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines [22] and as such did not require ethics committee approval. Each survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 [23], and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation [HIT] [24]. Fieldwork partners adhered to the national data collection regulations in China.

Data Availability

All data, i.e., methodology, materials, data and data analysis, that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to James Jackson at james.jackson@adelphigroup.com. James Jackson is an employee of Adelphi Real World.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Novick, D., Zhong, S. et al. Real-World Analysis of Clinical Characteristics, Treatment Patterns, and Patient-Reported Outcomes of Insufficient Responders and Responders to Prescribed Acute Migraine Treatment in China. Pain Ther 12, 751–769 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00494-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00494-1