Abstract

Introduction

Tapentadol has analgesic effects comparable to those of conventional opioids and is associated with fewer side effects, including gastrointestinal symptoms, drowsiness, and dizziness, than other opioids. However, the safety of tapentadol in the Japanese population remains unclear; the present multicentre study aimed to examine the safety of tapentadol and the characteristics of patients likely to discontinue this treatment owing to adverse events.

Methods

The safety of tapentadol was assessed retrospectively in patients with any type of cancer treated between August 18, 2014 and October 31, 2019 across nine institutions in Japan. Patients were examined at baseline and at the time of opioid discontinuation. Multivariate analysis was performed to identify factors associated with tapentadol discontinuation owing to adverse events.

Results

A total of 906 patients were included in this study, and 685 (75.6%) cases were followed up until tapentadol cessation for any reason. Among patients who discontinued treatment, 119 (17.4%) did so because of adverse events. Among adverse events associated with difficulty in taking medication, nausea was the most common cause of treatment discontinuation (4.7%), followed by drowsiness (1.8%). Multivariate analysis showed that those who were prescribed tapentadol by a palliative care physician (odds ratio [OR] 2.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.36–4.99, p = 0.004), patients switching to tapentadol due to side effects from previous opioids (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.05–4.56, p = 0.037), and patients who did not use naldemedine (OR 5.06, 95% CI 2.47–10.37, p < 0.0001) had an increased risk of treatment discontinuation owing to adverse events.

Conclusions

This study presents the safety profile of tapentadol and the characteristics of patients likely to discontinue this treatment owing to adverse events in the Japanese population. Prospective controlled trials are required to evaluate the safety of tapentadol and validate the present findings.

Trial Registration Number

UMIN 000044282 (University Hospital Medical Information Network).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Tapentadol has analgesic effects comparable to those of conventional opioids and is associated with fewer side effects than other opioids. |

The safety of tapentadol in the Japanese population and the characteristics of patients likely to discontinue this treatment owing to adverse events remain unclear. |

In particular, there have been no nationwide studies on the safety of tapentadol. |

What was learned from this study? |

This study showed that 17.4% of patients discontinued tapentadol owing to adverse events, the most common of which were nausea and drowsiness. |

Patients were most likely to discontinue tapentadol owing to adverse events when they were prescribed by a palliative care physician, switching to tapentadol due to side effects from previous opioids, and when they were not taking naldemedine. |

Concomitant use of naldemedine may reduce the risk of tapentadol discontinuation owing to side effects. |

Introduction

Cancer pain is associated with multiple factors and mechanisms. Pain is mainly classified into nociceptive and neuropathic pain. The prevalence of neuropathic pain has been estimated to be 19–39% among patients with cancer when mixed pain is included [1]. The mechanism of descending noradrenergic modulation may be an important component of neuropathic pain. Tapentadol (TAP) has a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitory effect in addition to a μ-receptor agonist effect and may be effective in neuropathic pain management. TAP is used for moderate to severe chronic pain management in some countries. However, in Japan, it is indicated for cancer pain. Previous randomized controlled trials have reported that the analgesic effect of TAP is comparable to that of oxycodone and morphine [2, 3].

Opioid treatment is associated with side effects that stem from the action of opioid and non-analgesic receptors. In clinical practice, the onset of intolerable side effects may lead to dose reduction, which may result in inadequate analgesic relief, triggering treatment discontinuation in approximately 30% of patients. Side effects of opioids include constipation, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, and sedation, of which constipation is the most common and persistent symptom [4, 5]. Controlling these symptoms is essential to the clinical application of opioids. Laxatives and antiemetics are often used along with opioids to control side effects. In clinical trials, naldemedine has been shown to improve opioid-induced constipation in patients without and with cancer [6]. It is a direct μ-receptor antagonist, known in basic research to improve intestinal hypoperistalsis [7].

TAP undergoes a predominantly glucuronic acid reaction rather than being metabolized by cytochrome P450, which makes it unlikely to trigger drug–drug interactions. TAP also has minimal serotonin effect, resulting in a relatively low risk of a serotonin syndrome [8]. Moreover, the combination of µ-opioid receptor activation and noradrenaline reuptake inhibition reduces the risk of adverse effects and improves TAP tolerability [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Previous studies have shown that TAP may cause fewer adverse events, such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, and drowsiness and dizziness, than other opioids [3, 15,16,17,18,19]. In fact, there is inadequate information on the side effects of TAP that could make its intake difficult for patients. The present study aimed to investigate the real-world safety of TAP treatment and the characteristics of patients likely to discontinue this treatment owing to adverse events.

Methods

This clinical study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committees at nine institutions: Yokohama City University Hospital (B191200005 dated December 20, 2019), National Cancer Centre Hospital (2019-330 dated April 9, 2020), National Cancer Centre Hospital East (2019-330 dated April 9, 2020), Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (2019-1247 dated April 6, 2020), Tohoku University Hospital (2019-1-978 dated March 23, 2020), Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital (133 dated January 8, 2020), University of Yamanashi Hospital (2214 dated April 1, 2020), Yokohama Minami Kyousai Hospital (1-19-12-11 dated January 15, 2020), and Toranomon Hospital (2133 dated December 16, 2020). The study was registered as UMIN 000044282 (University Hospital Medical Information Network).

Participants

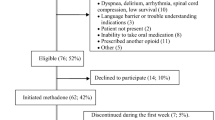

We enrolled patients with carcinoma who started taking TAP between August 18, 2014, the date of its launch in Japan, and October 31, 2019. Eligible patients were identified at nine institutions (Yokohama City University Hospital, National Cancer Centre Hospital, National Cancer Centre Hospital East, Cancer Institute Hospital of JFCR, Tohoku University Hospital, Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital, University of Yamanashi Hospital, Yokohama Minami Kyousai Hospital, and Toranomon Hospital). All patients who took TAP during the study period were included, but patients who met the exclusion criteria described below or who did not wish to participate in the study were excluded. The exclusion criteria included patients whose date of starting TAP was not recorded and those who were unsuitable for the study on the basis of the judgment of the investigators. Data were extracted from electronic medical records, and the date of the first TAP prescription was defined as the study index date. Patients with an unknown date of TAP initiation were excluded.

Patients were eligible for this study regardless of age, sex, prescribing physician, or treatment setting (outpatient or inpatient).

Measurement and Evaluation Items

Data on age, sex, tumour site, comorbid treatment, survival time, TAP treatment setting and duration, concomitant medication, treatment dosage, pre-induction opioid use, type of rescue medication, reason for starting/stopping TAP, and outcomes were collected. In addition, data on the use of laxatives (such as naldemedine), antiemetics, and analgesic aids as concomitant medication were collected.

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients discontinuing TAP owing to adverse events. The secondary endpoints included the rates of TAP discontinuation owing to adverse events within 28 days of initiation, change in concomitant medication use, reason for TAP treatment initiation, treatment setting, duration of prescription, and incidence of adverse events.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median ± interquartile range (IQR). Patients’ characteristics were compared between a group that discontinued TAP owing to adverse events and one that continued to take TAP; comparisons were made with a two-sided chi-square test for categorical variables; p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Variables with p < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model, examining factors associated with discontinuation of TAP due to adverse events. Variables with a significance level of p < 0.05 in the multivariable model were retained. Analyses were performed using JMP 14.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Data from a total of 906 (48.8% women; median age, 64 years) patients who met the inclusion criteria were analysed. The patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Tumour sites were the head and neck (n = 36, 4.0%); gastrointestinal tract (n = 167, 18.4%); lung (n = 191, 21.1%); breast (n = 93, 10.3%); liver, biliary tract, or pancreas (n = 119, 13.1%); urologic tract (n = 62, 6.8%); female reproductive system (n = 83, 9.2%); haematologic tissue (n = 21, 2.3%); skin (n = 19, 2.1%), soft tissue (n = 60, 6.6%), and thyroid (n = 6, 0.7%). In addition, 463 (51.1%), 101 (11.1%), 225 (24.8%), and 117 (12.9%) patients were treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, palliative care only, and other therapies, respectively.

Findings Before and After Tapentadol Use

At baseline, 277 (31.9%), 467 (53.9%), and 123 (14.2%) patients were opioid naïve, switched over from other opioids, and received TAP as an add-on treatment to other opioids, respectively. Among patients previously treated with opioids, the median oral morphine equivalent daily dose (OMEDD) before starting TAP was 40 mg/day. TAP was initiated in 259 (28.6%), 203 (22.4%), 33 (3.6%), and 411 (45.4%) palliative outpatients, general outpatients, inpatients in palliative beds, and inpatients in general beds, respectively. The median dose of TAP at initiation was 50 mg/day. TAP was prescribed to relieve nociceptive or neuropathic pain in 380 (42.0%) and 315 (34.8%) patients, respectively, and to manage side effects, such as nausea, constipation, drowsiness, and other side effects in 93 (10.3%), 21 (2.3%), 26 (2.9%), and 69 (7.6%) patients, respectively. Overall, 695 (83.2%) and 140 (16.8%) patients received TAP for pain and adverse event management, respectively (Table 2).

At baseline, 291 (32.6%) patients were opioid naïve. Meanwhile, 603 (67.4%) patients had used opioids before the initiation of TAP; among them, oxycodone was most used (n = 335, 37.5%). At baseline, tramadol, fentanyl, morphine, hydromorphone, and other opioids were used in 148 (16.6%), 53 (5.9%), 34 (3.8%), 12 (1.3%), and 21 (2.3%) patients, respectively. After treatment initiation, the median duration of TAP treatment was 28.5 days, including 451 (49.9%) and 452 (50.1%) patients that were prescribed TAP for at most 28 days and less than 29 days, respectively. While taking TAP, 715 (79%) patients were not taking concomitant opioids; in contrast, 191 (21%) patients were taking concomitant opioids, including oxycodone (n = 100, 11.0%), fentanyl (n = 33, 3.6%), morphine (n = 19, 2.1%), tramadol (n = 14, 1.5%), hydromorphone (n = 9, 1.0%), and other opioids (n = 16, 1.8%). The median daily dose of TAP during the prescription period was 200 mg/day; moreover, 797 (91%) patients took a TAP dose of less than 400 mg/day.

Reasons for Treatment Discontinuation

TAP was discontinued in 685 (75.6%) cases overall and in 119 (17.4%) cases owing to adverse events (Table 3). Among the cases, 153 (21.9%), 83 (12.1%), 8 (1.2%), 141 (20.6%), 90 (13.1%), 3 (0.4%), 30 (4.4%), and 23 (3.4%) cases of discontinuation were because of insufficient effect, pain relief, difficulty breathing, difficulty taking medication, hospital transfer, discharge home, death, and patient wishes, respectively. Among patients who discontinued TAP owing to adverse events, nausea, drowsiness, constipation, diarrhoea, delirium, cardiovascular symptoms, and other/unknown symptoms were reported in 32 (4.7%), 12 (1.8%), 1 (0.1%), 4 (0.6%), 8 (1.2%), 8 (1.2%), and 54 (44%) cases, respectively. A total of 311 (34.3%) patients discontinued TAP within 28 days of administration.

Factors Associated with Treatment Discontinuation

Comparisons between the groups that did and did not discontinue treatment are presented in Table 4. The following variables were consistently associated with treatment discontinuation owing to adverse events: treatment with opioids at baseline (p = 0.038), use of TAP as a part of supportive care (p = 0.003), prescription received from a palliative care physician (p = 0.022), receiving at least two tablets per dose (p = 0.004), treatment with naldemedine (p < 0.0001), and side effects because of which TAP was prescribed (p = 0.04). Multivariate analysis showed that patients who were prescribed TAP by a palliative care physician (odds ratio [OR] 2.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.36–4.99, p = 0.004), those switching to TAP due to side effects from previous opioids (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.05–4.56, p = 0.037), and those who did not use naldemedine (OR 5.06, 95% CI 2.47–10.37, p < 0.0001) were more likely than their counterparts to discontinue treatment owing to adverse events (Table 5).

Discussion

In the present study, 17.4% of patients who were followed up until TAP cessation discontinued TAP owing to adverse events, of which the most common were nausea and drowsiness. There was only one case of discontinuation due to constipation, suggesting the safety of TAP for constipation.

In a retrospective, single-centre study of 84 patients, none of the patients had to discontinue TAP because of its side effects [20]. In another retrospective study on 38 patients, only one patient (2.6%) had an adverse event of grade 3 or higher [21]. Compared with previous reports, more patients discontinued medication because of side effects in the present study. It may be difficult to compare the present study with previous studies because of the differences in the institutions participating in this study, the study protocol, and the patients’ backgrounds.

Patients were most likely to discontinue TAP owing to adverse events when they were switching to TAP due to side effects from previous opioids, prescribed by a palliative care physician, and when they were not taking naldemedine. The switch to TAP due to side effects was found to be a risk factor for discontinuation of TAP. This may indicate that a certain number of patients are less tolerant not only to TAP but also to opioids in general.

In addition, palliative care physicians are effective at recognizing treatment-related adverse events and changing their approach to care, as required, which may have contributed to the rates of TAP discontinuation. Another factor is that patients who consult a palliative care physician may have more advanced cancer, poorer general health, and lower opioid tolerance despite having more severe pain.

The use of naldemedine was significantly associated with adverse event-related TAP discontinuation; however, discontinuation due to constipation was observed only in one case. Naldemedine may relieve gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea. A previous study has shown that naldemedine may help prevent opioid-induced nausea and vomiting in patients treated with morphine or oxycodone [22]. Whether a similar effect is observed in different contexts requires further research.

The size of a TAP tablet is 17 mm in length in all standards. A previous study reported that the most desirable tablet size for a frail older adult was 7–8 mm, given their capacity for swallowing and handling [23]. TAP comes in large tablets, which may be difficult to swallow. In addition, tablet size may have accounted for 20.6% of discontinuation cases in the present study, which were related to swallowing difficulties.

This study has several strengths. First, this study included a large sample. Second, three-quarters of participants were followed up until the end of their treatment and the reasons for treatment termination were investigated. Finally, the present study was a multicentre study; thus, the present findings are more generalizable than those of single-centre studies.

Nevertheless, there are several limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective cross-sectional study, precluding meaningful conclusions regarding causality. Although we included a large sample of eligible patients, some bias may have remained. In addition, we could not evaluate pain management efficacy because of the lack of relevant data. Future prospective studies are required to fill this gap. Second, this was a single-arm study; thus, we did not compare the safety profile between groups; a study with treatment and control groups may help address this limitation. Third, this study may have been affected by selection bias, as the included patients were treated at several specialist medical institutions. Future studies should validate the present findings in general hospitals and among physicians that perform house calls. Fourth, the present findings may have been affected by rescue medication. Since the fast-release formulation of TAP is not available in Japan, other opioid types are used as the fast-release formulation. In this study, oxycodone accounted for 73% of the rescue drugs used, potentially affecting the present findings. Finally, the eligibility of the target population was not determined because this study was an all-cases survey. The general condition of patients may have influenced the results of this study.

Conclusions

The present findings provide preliminary insights into the safety profile of TAP use in the Japanese population and into the characteristics of patients likely to discontinue this treatment owing to adverse events. Concomitant use of naldemedine may reduce the risk of TAP discontinuation owing to side effects. Prospective controlled trials are required to evaluate the safety of TAP and validate the present findings.

References

Bennett MI, Rayment C, Hjermstad M, Aass N, Caraceni A, Kaasa S. Prevalence and aetiology of neuropathic pain in cancer patients: a systematic review. Pain. 2012;153:359–65.

Imanaka K, Tominaga Y, Etropolski M, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral tapentadol extended release in Japanese and Korean patients with moderate to severe, chronic malignant tumor-related pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1399–409.

Kress HG, Koch ED, Kosturski H, et al. Tapentadol prolonged release for managing moderate to severe, chronic malignant tumor-related pain. Pain Physician. 2014;17:329–43.

Coluzzi F, Berti M. Change pain: changing the approach to chronic pain. Minerva Med. 2011;102:289–307.

Mcnicol E, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, et al. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2003;4:231–56.

Katakami N, Harada T, Murata T, et al. Randomized phase III and extension studies of naldemedine in patients with opioid-induced constipation and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3859–66.

Kanemasa T, Koike K, Arai T, et al. Pharmacologic effects of naldemedine, a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, in in vitro and in vivo models of opioid-induced constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31: e13563.

Barbosa J, Faria J, Queiros O, Moreira R, Carvalho F, Dinis-Oliveira RJ. Comparative metabolism of tramadol and tapentadol: a toxicological perspective. Drug Metab Rev. 2016;48:577–92.

Giorgi M, Meizler A, Mills PC. Pharmacokinetics of the novel atypical opioid tapentadol following oral and intravenous administration in dogs. Vet J. 2012;194:309–13.

Hartrick CT, Rozek RJ. Tapentadol in pain management: a mu-opioid receptor agonist and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:359–70.

Meske DS, Xie JY, Oyarzo J, Badghisi H, Ossipov MH, Porreca F. Opioid and noradrenergic contributions of tapentadol in experimental neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2014;562:91–6.

Raffa RB, Buschmann H, Christoph T, et al. Mechanistic and functional differentiation of tapentadol and tramadol. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:1437–49.

Steigerwald I, Schenk M, Lahne U, Gebuhr P, Falke D, Hoggart B. Effectiveness and tolerability of tapentadol prolonged release compared with prior opioid therapy for the management of severe, chronic osteoarthritis pain. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33:607–19.

Tzschentke TM, Christoph T, Kogel BY. The mu-opioid receptor agonist/noradrenaline reuptake inhibition (MOR-NRI) concept in analgesia: the case of tapentadol. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:319–29.

Riemsma R, Forbes C, Harker J, et al. Systematic review of tapentadol in chronic severe pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1907–30.

Coluzzi F, Ruggeri M. Clinical and economic evaluation of tapentadol extended release and oxycodone/naloxone extended release in comparison with controlled release oxycodone in musculoskeletal pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1139–51.

Lange B, Kuperwasser B, Okamoto A, et al. Efficacy and safety of tapentadol prolonged release for chronic osteoarthritis pain and low back pain. Adv Ther. 2010;27:381–99.

Imanaka K, Tominaga Y, Etropolski M, Ohashi H, Hirose K, Matsumura T. Ready conversion of patients with well-controlled, moderate to severe, chronic malignant tumor-related pain on other opioids to tapentadol extended release. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:501–11.

Buynak R, Shapiro DY, Okamoto A, et al. Efficacy and safety of tapentadol extended release for the management of chronic low back pain: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled phase III study. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1787–804.

Sazuka S, Koitabashi T. Tapentadol is effective in the management of moderate-to-severe cancer-related pain in opioid-naive and opioid-tolerant patients: a retrospective study. J Anesth. 2020;34:834–40.

Sugiyama Y, Kataoka T, Tasaki Y, et al. Efficacy of tapentadol for first-line opioid-resistant neuropathic pain in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:362–6.

Sato J, Tanaka R, Ishikawa H, Suzuki T, Shino M. A preliminary study of the effect of naldemedine tosylate on opioid-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:1083–8.

Miura H, Kariyasu M. Effect of size of tablets on easiness of swallowing and handling among the frail elderly. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2007;44:627–33.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Michihiro Iwaki, Takaomi Kessoku, Takeshi Hirohashi, Atsushi Nakajima, Yasushi Ichikawa, and Hiroto Ishiki contributed to the study design. Michihiro Iwaki, Takaomi Kessoku, Taro Kanamori, Kentaro Abe, Nobuhiro Takeno, Ryoko Kawahara, Taisuke Fujimoto, Takashi Igarashi, Yasutomo Kumakura, Suzuki Naoki, Kouhei Kamiya, Naoto Suzuki, Keita Tagami, Saeki Tomoya, Hironori Mawatari, Hiroki Sakurai, and Hiroto Ishiki were responsible for data collection. Michihiro Iwaki, Takaomi Kessoku, and Takahiro Higashibata were involved in data analysis. All authors contributed to review and writing of the manuscript. Michihiro Iwaki, Takaomi Kessoku, and Hiroto Ishiki were responsible for the preparation of the tables.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The assistance of Kyoko Kato, Hiroyuki Abe, and Machiko Hiraga is gratefully acknowledged. The administrative assistance of Naho Kobayashi, Ayako Ujiie, and Yoshiko Yamazaki is also gratefully acknowledged. No funding was recieved for this assistance.

Disclosures

Michihiro Iwaki, Takaomi Kessoku, Taro Kanamori, Kentaro Abe, Nobuhiro Takeno, Ryoko Kawahara, Taisuke Fujimoto, Takashi Igarashi, Yasutomo Kumakura, Suzuki Naoki, Kouhei Kamiya, Naoto Suzuki, Keita Tagami, Saeki Tomoya, Hironori Mawatari, Hiroki Sakurai, Takahiro Higashibata, Takeshi Hirohashi, Atsushi Nakajima, Yasushi Ichikawa, and Hiroto Ishiki declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This clinical study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committees at nine institutions: Yokohama City University Hospital (B191200005 dated December 20, 2019), National Cancer Centre Hospital (2019-330 dated April 9, 2020), National Cancer Centre Hospital East (2019-330 dated April 9, 2020), Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (2019-1247 dated April 6, 2020), Tohoku University Hospital (2019-1-978 dated March 23, 2020), Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital (133 dated January 8, 2020), University of Yamanashi Hospital (2214 dated April 1, 2020), Yokohama Minami Kyousai Hospital (1-19-12-11 dated January 15, 2020), and Toranomon Hospital (2133 dated December 16, 2020). The study was registered as UMIN 000044282 (University Hospital Medical Information Network).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwaki, M., Kessoku, T., Kanamori, T. et al. Tapentadol Safety and Patient Characteristics Associated with Treatment Discontinuation in Cancer Therapy: A Retrospective Multicentre Study in Japan. Pain Ther 10, 1635–1648 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00327-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00327-z