Abstract

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are, in general, the cornerstone of musculoskeletal pain management; however, systemic adverse events with oral formulations of NSAIDs are common. To address this problem and limit systemic exposure, topical formulations of some NSAIDs have been developed. The aim of this systematic review was to assess the available evidence on the efficacy and safety of the topical formulations of the NSAID etofenamate in patients with musculoskeletal disorders.

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed and Web of Science was conducted using the key words “topical etofenamate efficacy” OR “topical etofenamate safety” OR “topical etofenamate effectiveness” to identify studies of etofenamate published from inception to November 2018. Some published manuscripts of interest known by the authors but not identified in the PubMed search were also included to ensure the review article was as comprehensive as possible.

Results

Overall, 12 studies were identified. These studies demonstrate that topical etofenamate [administered either in gel (5 or 10%), cream (10%) or lotion (10%) formulations)] can improve pain and reduce inflammation in patients with musculoskeletal disorders, including blunt injuries and rheumatic diseases. Etofenamate was shown to have an overall efficacy that was superior to other topical NSAIDs, such as 1% indomethacin and 1% diclofenac, and to be as effective as topical formulations of 2.5% ketoprofen gel and 2% ketorolac gel (although ketorolac showed better elimination of pain at some time points). Also, clinical evidence indicates that etofenamate is generally well tolerated in these indications.

Conclusions

The clinical evidence currently available suggests that etofenamate is an effective therapeutic option for the management of musculoskeletal disorders, such as blunt traumas, lumbago or osteoarthrosis. However, larger and well-controlled clinical trials comparing the efficacy and safety of etofenamate with other newer topical NSAIDs are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Available clinical evidence suggests that etofenamate is an effective therapeutic option for the management of musculoskeletal disorders, such as blunt traumas, lumbago or osteoarthrosis. |

Etofenamate is indicated in painful conditions of the locomotor system when the symptomatology is localised, such as in arthropathies, myalgias, bursitis, tenosynovitis, fibrositis, neuralgias (cervical syndrome, low back pain, sciatica), contusions, sprains, and strains (associated, for example, with sports injuries). |

Etofenamate has an overall efficacy and tolerability that are superior to other topical NSAIDs such as 1% indomethacin and 1% diclofenac, while being as effective as topical formulations of 2.5% ketoprofen gel and 2% ketorolac gel. |

Larger and well-controlled clinical trials comparing the efficacy and safety of etofenamate with other newer topical NSAIDs are warranted. |

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders affect millions of people of all ages around the world [1]. In the 2016 Global Burden of Disease study, the second greatest contributor to global disability was musculoskeletal conditions, with the consistent leading cause of disability since 1990 being lower back pain. The prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions varies according to patient age and diagnosis; however, an estimated 20–33% of people worldwide have painful musculoskeletal disorders [2]. This umbrella term covers a wide range of diagnoses that affect the locomotor system (muscles, bones, joints, spine and associated tissues such as tendons and ligaments) [1, 3]. These diagnoses include joint diseases, such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, back and neck pain, soft tissue rheumatism (tendinitis, bursitis and myofascial pain) or injuries from sports. The pain brought on by musculoskeletal conditions can significantly impact quality of life, including the ability to work, sleep and perform physical and social activities [1].

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are, in general, a key aspect of musculoskeletal pain management; however, adverse events (AEs) associated with their use are becoming increasingly evident. This common association between systemic NSAIDs and AEs (e.g. gastrointestinal and renal complications) has led to the development of topical NSAIDs formulations to limit systemic exposure. As topical formulations are locally applied to the affected region, they can provide effective drug concentrations at the location of musculoskeletal pain without resulting in systemic drug concentrations that may cause systemic AEs [4]. Topical NSAIDs are locally applied to unbroken skin at the site of pain in the form of a gel, cream, spray or plaster [5]; consequently, they could theoretically provide therapeutic drug concentrations in the tissues near the site of application, while serum drug concentrations remain relatively low and safe. This mechanism of action would exclude first pass metabolism of NSAIDs, thereby preventing gastrointestinal AEs and reducing the risk of toxicity associated with the high serum drug concentrations that are often required for systemic dosage forms to be effective [4].

The efficacy of topical NSAIDs in osteoarthritis (OA) (in particular, knee OA) has been established in randomised clinical trials and meta-analyses [6]. Head-to-head studies have demonstrated that topical NSAIDs have similar efficacy as oral NSAIDs in patients with knee OA, while having a lower risk of gastrointestinal AEs, although the risk of mild skin reactions is increased [6]. The efficacy of topical NSAIDs is dependent on high levels of absorption through the skin and drug accumulation in the target tissues, as well as low serum concentrations, thereby improving tolerability through the prevention of systemic toxicities [6].

In England, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended topical therapies as first-line treatment in its guidelines for OA in 2008 [7], and in 2014 the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) also recommended topical therapies for individuals with knee-only OA (quality of evidence: good) [8]. In 2016, the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) considered topical NSAIDs therapy as the first step of the pharmacological treatment of symptomatic knee OA [6]. However, although many NSAIDs are available, only a few are used as topical therapeutics, primarily because the physicochemical properties of these substances, which were originally developed for oral administration, frequently do not guarantee a satisfactory pharmaceutical formulation with sufficient absorption [9].

Etofenamate, 2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethyl-N-(α,α,α-trifluoro-m-tolyl)anthranilate, an NSAID developed for topical treatment, is a derivate of flufenamic acid and belongs to the group of NSAIDs referred to as anthranilic acid derivates [10]. The synthesis of etofenamate was specifically designed to enable the preparation of new substances that would meet the requirements for a topical anti-inflammatory treatment, such as adequate anti-inflammatory and analgesic efficacy, good local and systemic tolerability and good transcutaneous penetrating ability. Etofenamate owes its physicochemical properties to its typical alcohol–ether–ester structure, and it is this structure that gives this molecule its high lipophilicity. Compounds with a free carboxyl group demonstrate different lipophilic behaviour, which because of the dissociation at the carboxyl group, varies according to pH, thereby affecting the penetration, absorption and distribution of the compound in the organism [10]. Unlike a number of other NSAIDs which exclusively inhibit cyclooxygenase [11], etofenamate is not only capable of inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, but it is also a strong inhibitor of leukotriene synthesis since it inhibits both lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase [12, 13]. Etofenamate also acts in other inflammatory pathways, such as the inhibition of the release of histamine, antagonism of bradykinin and serotonin, inhibition of the activity of the complement system and inhibition of hyaluronidase [14,15,16].

Studies of etofenamate in humans have shown that following cutaneous application, etofenamate levels are much lower in the plasma than in tissues. In one study, etofenamate levels were 10- to 1000-fold higher in fasciae, muscles and the periosteum than in plasma [17]. Following local dermal administration of 300 mg etofenamate, the bioavailability of this NSAID was 21% (based on the renal elimination of the active ingredient), which is greater than that of diclofenac (6%), ibuprofen (5%), indomethacin (1%) and ketoprofen (1%) and more consistent than that of salicylic acid (range 1–23%) [11, 18]. Studies have also demonstrated the capacity to achieve the desired concentration of the anti-inflammatory etofenamate in inflamed tissues and that at the same time plasma levels were low and there was little systemic burden on the body [19].

Etofenamate is indicated in the treatment of painful disorders of the locomotor system since the symptomatology is localised, such as arteriopathies, myalgia, neuralgia, contusions, strains or sprains. The duration of treatment varies according to the clinical situation to be treated. In the case of rheumatic diseases, treatment for 3–4 weeks is usually sufficient in most cases. The duration of treatment for acute trauma (e.g. associated with sports) may be extended to 2 weeks [14,15,16].

The objective of this article was to review the efficacy and safety data on topical formulations of etofenamate in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Web of Science databases to identify all eligible articles for inclusion in this review. A search string that could efficiently identify all articles evaluating the safety and/or efficacy of etofenamate was developed and all the articles published from inception to November 2018 were selected. The search terms used were: “topical etofenamate efficacy” OR “topical etofenamate safety” OR “topical etofenamate effectiveness”. Other relevant articles known to the authors or listed in the bibliographies of identified articles were also included.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

There were no restrictions on trial duration or patient sex. Trials using topically administered preparations of etofenamate, of any dose (5 or 10%) or pharmaceutical presentation (gel, cream or lotion), were considered. Comparison interventions included placebo or an active substance (both topically applied). No date restrictions were applied to the search. Studies in patients who in addition to the test substances also required other analgesics/anti-inflammatories were excluded. Studies in animals were also excluded.

Outcomes

Each article identified was assessed and data regarding inflammation symptoms (spontaneous pain, pain on motion, tenderness) and the incidence of AEs were extracted.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Search Results

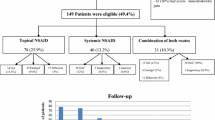

Our search strategy resulted in the identification of 13 articles (8 from Pubmed and 5 from Web of Science). In order to ensure the comprehensiveness of this systematic review article, 9 previous publications of interest that were known by the authors but not identified in the PubMed search were also added (Fig. 1). After assessing the eligibility of each article, 12 studies were included (Fig. 1).

Study Designs and Patients

Of the 12 studies included in this review, nine were randomised clinical trials, three were open-label multicentre trials, three were single-blind studies and six were double-blind studies (Table 1). The duration of these 12 studies ranged from 1 day to 6 weeks, with a mean study period of 3 weeks. A total of 14,780 patients were included in the 12 trials. Sample sizes ranged from 36 to 7477, with a median size of 143 patients. All studies recruited male and female patients.

Etofenamate Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability

Etofenamate Lotion

The efficacy and tolerability of a 10% etofenamate lotion was investigated in a multicentre, non-comparative study in 7477 patients with acute or chronic rheumatic diseases, including lumbago, bursitis, blunt injury, sciatica, myositis, periarthropathia humeroscapularis and tendovaginitis [9]. The treatment was administered up to 3–4 times per day until the onset of symptom freedom, or for no longer than 21 days (mean 16 ± 8 days; 41.5% of patients received treatment for < 2 weeks, 36.7% for ≤ 3 weeks, 20% for > 3 weeks). Outcomes included the severity of the symptoms of the diseases (spontaneous pain, pain on movement, tenderness, functional impairment, swelling or reddening) and were assessed at screening and after 7, 14 and 21 days of treatment.

At the time of last examination (which was performed at different times in different individuals), 58.8% of the patients who had had spontaneous pain before the treatment were free from this symptom, while the intensity of spontaneous pain was reduced in 37.0% of patients [9]. Therefore, 95.8% of patients were considered to have achieved a successful therapeutic outcome. Pain on movement disappeared completely in 37.2% of patients and decreased in 58.6% (therapeutic success rate 95.8%). Tenderness was eliminated in 46.7% of patients and alleviated in a further 48.0% (therapeutic success rate 94.7%). For functional impairment, the remission rate was 48.8% and the improvement rate 44.5% (therapeutic success rate 93.3%); for swelling, these rates were 76.3 and 18.7%, respectively (therapeutic success rate 95.0%). Reddening disappeared in 86.6% of the affected patients and decreased in the 10.6% (therapeutic success rate 97.2%). The remission rates with etofenamate lotion differed depending on the indication that was being treated. The treating physician’s final assessment of the outcome of the therapy was “very good” in 37.5% of patients, “good” in 40.2%, “satisfactory” in 13.9% and “unsatisfactory” in 6.7% (no data for 1.7%). In comparison, 37.8% of patients evaluated the treatment as “very good”, 38.5% as “good”, 13.8% as “satisfactory”, and 7.4% as “unsatisfactory” (no data for 2.5%). Unwanted local AEs were reported by 85 patients (1.1%) and necessitated a premature discontinuation of treatment in 39 patients (0.5%) [9].

Etofenamate Cream

A multicentre, randomised, controlled, single-blind study of 70 patients with acute lumbago compared the efficacy and tolerability of etofenamate cream (1 g of cream contained 100 mg of etofenamate) with an indomethacin ointment (1 g of ointment contained 50 mg of indomethacin and 50 mg of polidocanol) [20]. Treatment was applied 3 times a day, in a quantity equivalent a length of to 5–10 cm, until the symptoms resolved, or for no longer than 9 days (mean duration of treatment 8.5 days). Outcomes included spontaneous pain, pain on movement, pain under pressure, spine mobility (measured using the Schober’s test and finger–fibula distance).

In the etofenamate group, spontaneous pain decreased continuously in an approximately linear manner until the seventh day. In contrast, in the indomethacin group, there was practically no improvement observed after the fourth day of treatment [20]. After 7 days of treatment, those receiving etofenamate reported significantly reduced spontaneous pain compared with those receiving indomethacin (64 vs. ~ 25% reduction; p < 0.001). After 4 days of treatment, the pain on mobilization was significantly less intense in the etofenamate group than in the indomethacin group (p < 0.01), and after 7 days of treatment, there was a 56% decrease in pain on mobilization in the etofenamate group and a 31% decrease in the indomethacin group. Pain under pressure was also significantly decreased after 7 days on etofenamate versus indomethacin (56 vs. 24%; p < 0.01). Furthermore, significantly more patients receiving etofenamate had their pressure pain eliminated or improved compared with those receiving indomethacin (96 vs. 55%; p < 0.001). After 7 days of treatment, spine mobility was significantly improved in the etofenamate group, with an increase in Schober distance of 1.8 cm compared with an increase of 0.9 cm in the indomethacin group (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the improvement in lateral flexion was more pronounced in the etofenamate group than in the indomethacin group; after 7 days of treatment etofenamate was associated with numerically greater (but not statistically significant) reductions in finger–fibula distance compared with indomethacin [− 6.5 (right side) and − 7.0 cm (left side) vs. − 2.7 (right side) and − 2.8 cm (left side), respectively]. Etofenamate was generally well tolerated; cutaneous erythema (temporary and circumscribed in the area of application) was reported in two patients who do not require treatment interruption. No other AEs were reported [20].

A single-blind, randomised, controlled study in 40 patients with gonarthrosis investigated the efficacy and tolerability of 10% etofenamate cream compared with a preparation containing salicylic acid (100 g of ointment containing 12.5 g of (2-hydroxyethyl)-salicylate, 10,000 units of sodium heparin and camphor 1 g) [21]. Treatment was administered > 3 times a day or as needed for 21 days, and outcomes included tenderness, pain on movement and spontaneous pain. Outcomes were assessed by the investigators using a 6-step scale that ranged from “non-existent” to “very strong”.

At the end of the study (after 21 days), the difference between patients experiencing spontaneous pain was more favourable for those receiving etofenamate, with a statistically significant superiority [21]. Significantly greater improvements in pain during movement were observed with patients on etofenamate after 7 days, and at 21 days, 82.5% of etofenamate and 39.6% of salicylic acid patients showed an improvement in their pain during movement. Similar results were observed with the tenderness parameter, with significant differences between groups seen after 7 days of treatment and an improvement in tenderness seen in 78.3 and 32.0% of patients receiving etofenamate and salicylic acid, respectively, after 21 days. No significant differences in the change from baseline in mobility of the knee joints and circumference of the knee joints were observed between treatment groups, and both treatments were well tolerated [21].

In an open-label multicentre study in 4571 patients with various rheumatic diseases and blunt injuries, the effects of etofenamate 10% cream (administered until complete disappearance of symptoms, or up to a maximum of 21 days) on pain, impaired joint function and swelling, as well as tolerability, were investigated [12]. Patients had myalgia, periarthropathia humeroscapularis, lumbago, ischialgia, bursitis, tendinitis, tennis elbow, activated arthrosis, contusion, distortion, dislocation, sprain, spinal syndrome or other musculoskeletal conditions. Using a rating scale ranging from 0 to 10, changes in spontaneous pain, pain on movement and pain on pressure as well as impaired function, other signs and symptoms of inflammation and AEs were assessed. The mean duration of treatment was 14 ± 10 days. At the end of the scheduled treatment period, spontaneous pain disappeared completely in 53.7% of patients and was reduced in a further 41.7% of patients [12]. The pain on pressure was eliminated completely in 40.2% of patients, and its intensity was reduced in another 55.6%. Functional impairments disappeared completely in 48.4% of patients and partially in 46.1%. At the end of the treatment period, swelling and reddening were no longer detectable in 66.3% of the patients and had become less pronounced in 30.3%. The remission rate recorded for the pain on movement was 35.8%; however, 60.9% of the patients felt a reduction in the pain upon movement. Patients with a shorter duration of their complaint at the start of therapy showed a greater improvement with etofenamate. If the symptoms had existed for < 4 days at the start of treatment, the therapeutic success rate was 98.6% for spontaneous pain, 99.0% for pain on movement, 98.6% for pain on pressure, 98.4% for impaired function and 98.2% for the other signs and symptoms of inflammation. The lowest remission rates were obtained in the group of patients with activated arthrosis. Local AEs were reported by 294 (6.4%) patients, of which, in the opinion of the investigators, 113 AEs (2.5%) were definitely related to treatment, 91 AEs (2.0%) were possibly related and 63 AEs (1.4%) were probably related [12].

Etofenamate Gel

A randomised, controlled, single-blind, parallel-group study compared the efficacy and tolerability of 10% etofenamate gel with 1% diclofenac gel in 60 patients with contusions, dislocations and sprains resulting from sports injuries [22]. Treatment with etofenamate (2–3 times per day) or diclofenac (3–4 times per day) was administered until the patient was free from pain, or for a maximum of 7 days. The pain associated with the injury (spontaneous pain, pain on movement, tenderness, impaired function, swelling, redness, and loss of mobility) was assessed using a scale of intensity ranging from 0 (not present) to 10 (extremely severe).

Upon completion of etofenamate treatment, the pain, restricted mobility and inflammation associated with the injuries had been eliminated or alleviated in all patients [22]. Spontaneous pain disappeared in 63.3% of patients receiving etofenamate (compared with 24.1% of patients receiving diclofenac) and was alleviated in a further 36.7%. Pain on movement was eliminated in 43.3% of patients (vs. 20.7% for diclofenac), and tenderness disappeared in 23.3% (vs. 3.5% for diclofenac); these symptoms were alleviated in 56.7 and 76.7% of patients, respectively. Restrictions of function disappeared completely in 46.7% (vs. 20.7% for diclofenac) and partially in 53.3% of patients, whereas swelling, redness and haematomas were no longer present in 43.3% of patients (vs. 13.8% for diclofenac) and were less pronounced in 56.7%. Loss of mobility was eliminated in 56.7% of patients (vs. 13.8% for diclofenac), and mobility was improved in the other 43.3%. After only 2 days of treatment, etofenamate was considered superior to diclofenac in terms of outcomes, with a higher percentage improvement in all the symptoms evaluated compared to diclofenac. The proportion of patients with unchanged symptoms was also larger in the patient group receiving diclofenac treatment. Upon completion of treatment, the physicians’ assessment of etofenamate was considered “very good” in 70.0% of patients, “good” in 26.7% and “satisfactory” in 3.3%. No physician classified the treatment with etofenamate as “not satisfactory”. Regarding diclofenac, physicians considered the treatment to be “very good” in 17.2% of patients, “good” in 27.6%, “satisfactory” in 41.4% and “not satisfactory” in 13.8%. The patients’ overall assessment of each treatment was similar, and the difference between treatments was significant for both the physicians’ and the patients’ assessments (p < 0.01). No AEs were observed in either treatment group [22].

An open-label multicentre trial in 1880 male and female outpatients with OA with acute periarticular soft tissue pain investigated the efficacy and tolerability of 5% etofenamate gel applied 3 times daily [23]. Treatment was administered until the patient was free of symptoms, which in most patients was 14–28 days. Clinical parameters, such as pain at rest, pain on movement, pain on pressure, impaired joint function and joint swelling, were assessed. At the end of treatment, elimination or improvement was observed in spontaneous pain in 87.4% of the patients, pain on movement in 90.9% and pain on pressure in 82.9%. In addition, swelling was eliminated or improved in 82.4% of patients and functional impairment in 73.1%. AEs were limited to local skin irritations, which occurred in 2.8% (n = 52) of patients [23].

A randomised, double-blind, controlled study compared the efficacy and tolerability of 5% etofenamate gel with 1% indomethacin gel in 242 patients with knee OA [24]. Treatment was applied 3–4 times a day for 4 weeks. Combined use of physical therapy was permitted if the patient was receiving physical therapy before the initiation of the study and it could not be discontinued, or where the physical therapy was considered not to influence the evaluation of efficacy in this study. Outcomes included changes in pain (spontaneous pain, tenderness, pain on movement), inflammation (swelling, retention of synovial fluid, local burning sensation) and limitation of movement (limitation of movement and impairment in acts of daily living). Compared with indomethacin, etofenamate significantly improved spontaneous pain at 2 and 4 weeks, swelling at 2 weeks and limitation of movement at 4 weeks (all p < 0.005). After 4 weeks of treatment, etofenamate also improved pain on movement compared with indomethacin, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant (p < 0.10). No significant changes in other outcomes between treatment groups were observed. AEs were reported by two (1.7%) patients receiving etofenamate and 11 (9.7%) patients receiving indomethacin (p < 0.05) [24].

Another randomised, double-blind, controlled clinical study compared the efficacy and safety of 5% etofenamate gel with Mobilat ointment (composed of a heparinoid substance, adrenal extracts and salicylic acid 20 mg/g) in 184 patients with OA in the knee [25]. Outcomes included spontaneous pain, pain on motion, tenderness, range of motion, swelling and walking difficulty, which were all rated on a 4-point scale (severe, moderate, slight, none). Compared with salicylic acid, patients considered etofenamate significantly (p < 0.05) superior at all time points assessed (at 1 and 2 weeks of treatment and at the final evaluation). In addition, physicians considered etofenamate to have significantly improved overall symptoms at the final evaluation compared with salicylic acid (p < 0.05). Finally, compared with salicylic acid, etofenamate significantly improved range of motion at 1 and 2 weeks of treatment and at the final evaluation, walking difficulty at the final evaluation and overall severity of symptoms at the final evaluation (all p < 0.05). Both treatments were generally well tolerated, with 83.0 and 81.8% of etofenamate and salicylic acid recipients rating their treatment as “quite safe”. AEs were reported by two (2.3%) patients receiving etofenamate and three (3.4%) patients receiving salicylic acid; no significant difference in AEs was found between the two groups. The severity of these AEs was considered moderate in two patients (one in the etofenamate group and one in the salicylic acid group) and slight in the remaining three patients [25].

A randomised, double-blind controlled trial compared etofenamate gel 5% (3 times per day) with placebo in 143 patients with strains and sprains of the ankle or knee joint and bruising of the knee joint [26]. The observation period was approximately 21 days or until the end of therapy. Outcomes included the circumference of the joint and the joint mobility, determined using the “neutral position method”, as well as spontaneous pain, tenderness and pain on movement, which were assessed according to a 6-point scale (0 = not present to 5 = very severe). Depending on the diagnosis, treatment with etofenamate was significantly superior to placebo for nearly all parameters. In patients with distension strain of the capsular ligament of the ankle joint, spontaneous pain, pain on movement and tenderness were significantly improved with etofenamate compared with placebo (p < 0.05). In patients with knee joint contusion, the improvements in pain on movement and tenderness were also significantly better with etofenamate (p < 0.01); the same applies with this indication for spontaneous pain (p < 0.001; Table 2). In patients with slight ligament injuries of the knee joint, no statistically significant differences were found between treatments. Comparing the mean duration of treatment to complete symptom relief, with the exception of pronation and supination in the ankle joint, markedly shorter treatment times were seen with etofenamate than with placebo (Table 3). The skin compatibility of treatments was almost equally good for all patients; allergic reactions and other AEs were not observed [26].

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 40 patients with sprained ankles due to sports injuries evaluated the efficacy of 5% etofenamate gel in combination with ultraphonophoresis [27]. Instead of the normally used contact gel, patients were treated with etofenamate or with placebo. The aim of the study was to clarify, under controlled conditions, whether the effectiveness of ultraphonophoresis in the treatment of ankle sprains can be increased by simultaneous application of etofenamate. Assessment was based on evaluation of the reduction of swelling in the affected ankle and restoration of mobility. With the exception of weekends, the ultrasound treatment was administered for 14 days, each for 15 min. Outcomes included spontaneous pain, pain on movement, tenderness, functional limitation and swelling/reddening. After 14 days of treatment, the remission rates for the symptoms evaluated were significantly higher in the etofenamate group than in the placebo group. The rate of symptom remission in the etofenamate group compared with the placebo group was 90 versus 40% of patients, respectively, for spontaneous symptoms, 85% versus 20% for mobility symptoms, 75% versus 15% for tenderness, 85% versus 15% for functionality and 75% versus 25% for swelling/redness. Etofenamate was well tolerated, and skin irritation was comparable between the two treatment groups (n = 5 vs. n = 2) [27].

A randomised, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study compared the efficacy and safety of 15 days of treatment with 5% etofenamate gel versus 2% ketorolac gel at reducing inflammation and pain due to an ankle sprain without occlusion [28]. Outcomes included pain at rest, on movement, and at night, all measured on visual analogue scales (VAS), ankle volume and verbal rating of pain. A total of 37 patients were included in the study, of whom 13 received ketorolac, 12 received placebo and 12 received etofenamate. Regarding ankle volume, the biggest decreases were seen with etofenamate and ketorolac compared with much smaller decreases seen with placebo (p = 0.002 for ketorolac vs. placebo; there was no significant difference for etofenamate vs. ketorolac). After 4 days of treatment, the median changes in pain at rest were − 18, − 25 and − 12 mm with etofenamate, ketorolac and placebo, respectively (p = 0.003 for ketorolac vs. placebo; p = 0.015 for ketorolac vs. etofenamate). Regarding pain on movement, there were statistically significant differences between ketorolac and etofenamate or placebo on days 4 and 8, but these differences showed marginal significance at day 2. Ketorolac was associated with a lower incidence of VAS pain at night than etofenamate or placebo, with the difference versus placebo being statistically significant. The verbal ratings of pain severity showed greater improvements with ketorolac than with placebo, the difference reaching statistical significance by day 4; this parameter did not significantly differ between the ketorolac and etofenamate groups. AEs were minor, with only two reported (one each in the ketorolac and etofenamate groups), and no clinically relevant changes in vital signs were observed [28].

The efficacy and safety of twice-daily topical application of 2.5% ketoprofen gel and 5% etofenamate gel were investigated in a 7-day, randomised, controlled, double-blind clinical trial of 36 patients with inflammation of tendons, sheaths and bursae [29]. Outcomes included pain scale, morning stiffness, pain on active and passive movement and functional capacity. After 7 days of treatment, both treatments effectively reduced pain on active movement (p < 0.05). Pain on passive movement was more improved with ketoprofen (p < 0.01 vs. baseline) than with etofenamate (p = not significant); however, functional capacity was significantly improved only with etofenamate (p < 0.05) after 7 days of treatment. Pain was also significantly reduced with both ketoprofen and etofenamate after 7 days of treatment (both p < 0.01 vs. baseline), with neither treatment providing significant improvements in morning stiffness. No AEs were reported in either group [29].

Finally, it is important to note that one study that compared the efficacy and tolerability of 10% etofenamate gel versus indomethacin was excluded from this review due to the lack of information on the concentration of the competitor used in the study [30].

Discussion

The efficacy of topical NSAIDs in patients with slight to mild OS has been established in randomised clinical trials and meta-analyses. Evidence from head-to-head studies show that topical NSAIDs can be as effective as oral NSAIDs, but with a lower risk for gastrointestinal AEs; consequently, they are considered to be an appropriate first-line therapy option in some guidelines [6, 8, 31, 32]. The efficacy and tolerability of one such topical NSAID, etofenamate, were demonstrated in a randomised study of 60 football players with sports injuries, with the results showing that 10% etofenamate cream has equal efficacy as oral naproxen, but with a better tolerability profile [33]. Based on the positive results of this study, the aim of this systematic review was to further examine all evidence of the efficacy and safety of topical etofenamate for the management of musculoskeletal disorders.

This systematic review included 12 studies that involved a total of 14,780 patients with musculoskeletal disorders. These 12 studies evaluated the efficacy and safety of etofenamate in a variety of disorders in the context of sports injuries, such as contusions, sprains and strains, as well as in patients with myositis and other rheumatic diseases, such as lumbago, gonarthrosis and bursitis, to name only a few. The most frequently assessed outcomes in these studies were spontaneous pain, pain on motion, tenderness, swelling and incidence of AEs.

In patients with sport injuries, the authors of one study observed that 10% etofenamate gel was superior to 1% diclofenac gel in all of the studied parameters, leading them to conclude that this difference may be due to the difference in the absorption characteristics of the treatments (~20% with etofenamate and 6% with diclofenac) [22]. The safety profile of both substances was positive since no AEs were observed either treatment group [22]. The authors of another study reported that, compared with placebo, 5% etofenamate gel significantly improved spontaneous pain, pain on movement and tenderness in patients with strains and sprains of the ankle or knee joint and bruising of the knee joint [26]. In the case of slight ligament injuries of the knee joint, this study found no statistically significant differences in the investigated parameters. Finally, comparing the mean duration of treatment to complete symptom relief, with the exception of pronation and supination in the ankle joint, markedly shorter times to symptom relief were observed in those patients receiving etofenamate, which may indicate that an overall shorter duration of therapy is required [26]. In one study etofenamate was given in combination with ultraphonophoresis to patients with sprained ankles due to sports accidents; the authors reported that the effectiveness of pain treatment with ultrasound was increased when a contact gel containing etofenamate was used instead of a gel without any active substance (i.e. placebo) [27]. In addition to etofenamate having a greater effect on reduction in spontaneous pain, reduction in pain on movement and reduction in pain on pressure in comparison with placebo, it also had an anti-inflammatory effect. Ankle swelling and signs of inflammation, such as reddening, were reduced more rapidly and to a greater extent with etofenamate than with placebo. Finally, in this study the remission rates at 14 days of treatment for the individual symptoms ranged from 75 to 90% with etofenamate [27], which are comparable with those attained in open therapeutic studies with the combination of ultrasound and etofenamate [34, 35].

Based on the results of these studies, we believe that etofenamate may be recommended for the treatment of mild, blunt sports injuries.

Analysis of the results of an open-label trial involving patients with rheumatic diseases led the authors to conclude that 10% etofenamate lotion could be a product that is suitable for the treatment of acute and chronic rheumatic diseases [9]. These results also indicate that the tolerability of 10% etofenamate lotion, with an incidence of AEs of 1.1%, could be regarded as very good [9]. These findings were supported by another study conducted by Rechziegler and Bernuth [12], which showed a therapeutic success rate with etofenamate of ~ 90%. These authors also reported that etofenamate was well tolerated in both younger (< 60 years) and older patients (> 60 years), which was the first time a study specifically examined the possibility of relevant differences between younger and older patients in their tolerability of a topical NSAID [9]. Another study demonstrated that both ketoprofen and etofenamate were able to induce remission of inflammatory symptoms in patients with soft tissue rheumatic pain [29]. Interestingly, there were no reports of local irritation or systemic AEs with both treatments. The authors concluded that both drugs had good effects on the soft tissue inflammation in their patients and, in particular, had good effects on patients with inflammation of the periarticular structures of the knee, namely, the anserine bursa [29].

In a study involving patients with acute lumbago, it was found that both 10% etofenamate cream and indomethacin ointment are effective treatment options [20]. However, etofenamate treatment was significantly superior to indomethacin at improving spontaneous pain, pain on movement, pain under pressure and mobility (assessed using the Shober’s test). Furthermore, an improvement in lateral flexion was more pronounced in patients receiving etofenamate, but the difference between groups did not reach significance. In this study, plasma etofenamate levels were not measured, so the authors could not determine if the superiority of etofenamate cream was due to a greater absorption or a superior concentration of this substance in the tissues.

In patients with gonarthrosis, 10% etofenamate cream was found to be significantly superior to a salicylic acid ointment in all assessed pain parameters after 21 days [21]. With the parameters “tenderness” and “pain on movement”, this superiority was observed as early as after 7 days of treatment. However, no significant difference between treatments was observed when the range of movement or circumference of the affected joint was assessed. Both treatments were also well tolerated. Matsuno and colleagues compared the usefulness of 5% etofenamate gel with that of 1% indomethacin gel in patients with knee OA and found that, in general, etofenamate was more effective than indomethacin [24]. Spontaneous pain, tenderness and limitation of movement were significantly improved with etofenamate versus indomethacin, while pain on movement tended to be improved with etofenamate. There were no significant differences in swelling, retention of synovial fluid, local burning sensation and impairment of activities in daily living between treatment groups. No significant AEs were reported with etofenamate treatment [24]. Nagaya and colleagues compared the use of 5% etofenamate gel with a salicylic acid ointment in patients with knee OS and found that etofenamate significantly improved range of motion, walking difficulty and overall severity compared with salicylic acid [25]. However, there were no significant differences in improvements in spontaneous pain, pain on motion, tenderness and swelling between groups. Overall safety was rated as “absolutely safe” by 83.0% of patients in the etofenamate group and 81.8% of patients in the salicylic acid group [25].

The efficacy of 5% etofenamate gel was evaluated in an open trial of patients with OA and acute periarticular soft tissue pain. Clinical parameters, such as pain at rest, pain on motion, pain on pressure, impaired joint function and joint swelling, were assessed, based on which—depending on the patient’s illness—therapeutic success was declared after 23 days of treatment in 73–91% of those enrolled [23]. The physician’s overall assessment of the efficacy of etofenamate was “very good”, “good” or “moderate” in 94.8% of patients, and AEs were limited to local skin irritations.

Based on the results of these studies, we believe that etofenamate may be recommended for the treatment of rheumatic diseases.

Finally, one of the studies included in this review examined the efficacy of topically applied ketorolac in patients with pain due to ankle sprains and compared its effect with that of placebo and etofenamate (since the latter’s effects have been well studied and distinguished from those of placebo in a number of studies) [28]. The authors found that the greatest decreases in ankle volume were observed with etofenamate and ketorolac compared with placebo; however, there was no significant difference between the two active treatments. Regarding the ability to reduce swelling, ketorolac did not differ from etofenamate at the end of the study period; however, ketorolac significantly improved pain at rest and pain on movement compared with etofenamate. Furthermore, ketorolac and etofenamate both improved verbal ratings of pain severity, with no significant difference between the two active comparators. Both drugs were well tolerated.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this analysis. When conducting the literature searches for studies to include in this review, we found a lack of recent clinical data on topical etofenamate. Moreover, even though the search strategy was comprehensive, it is possible that pertinent unpublished reports or published studies were unintentionally missed. In order to have a more comprehensive view of all the studies conducted with topical etofenamate, some published manuscripts of interest known by the authors were included, which, however, are not indexed on Pubmed or Web of Science. The degree of rigour with which the studies were conducted was also not certain, essentially because of insufficient information on blinding procedures. Moreover, in some blinded studies, the evaluated drugs differed slightly in terms of appearance and odour due to differences in the pharmaceutical preparation process; consequently, blinding was not guaranteed. The studies included also had various methodologies (open label, single blind and double blind).

Conclusions

Etofenamate is a molecule that has been formulated to exert anti-inflammatory action through topical application. Its efficacy is likely related to its chemical structure (no carboxyl group and high degree of lipophilicity, residual hydrophilicity) and pharmacological (bioavailability of 21%; inhibition of not only cyclooxygenase but also lipoxygenase) characteristics. Etofenamate is indicated in painful conditions of the locomotor system when the symptomatology is localised, such as in arthropathies, myalgias, bursitis, tenosynovitis, fibrositis, neuralgias (cervical syndrome, low back pain, sciatica), contusions, sprains and strains (associated, for example, with sports injuries).

Multiple formulations of etofenamate are available, and gel (5 and 10%), cream (10%) and lotion (10%) formulations have been identified and studied. These relevant studies support the use of etofenamate to treat the indications mentioned above and have demonstrated that etofenamate has an overall efficacy and tolerability assessment that is superior to other topical NSAIDs, such as 1% indomethacin and 1% diclofenac, and that it is as effective as topical formulations of 2.5% ketoprofen gel and 2% ketorolac gel (although findings on ketorolac suggest a better elimination of pain at some time points). Studies of etofenamate versus placebo also demonstrate the efficacy and tolerability of this drug. However, larger and well-controlled studies to further establish and directly compare the efficacy and tolerability of etofenamate with other new topical NSAID formulations are warranted.

References

Atchison JW, Herndon CM, Rusie E. NSAIDs for musculoskeletal pain management: current perspectives and novel strategies to improve safety. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19:S3–19.

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59.

World Health Organization. Musculoskeletal conditions: fact sheet. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/musculoskeletal/en/. Accessed 21 Nov 2018.

Haroutiunian S, Drennan DA, Lipman AG. Topical NSAID therapy for musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2010;11:535–49.

Derry S, Conaghan P, Da Silva JA, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD007400.

Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:253–63.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis: care and management. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177. Accessed 21 Nov 2018.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22:363–88.

Pelster B, Bernard I. Local treatment of acute and chronic rheumatic diseases [Lokaltherapie akuter und chronischer rheumatischer erkrankungen]. ZFA. 1992;68:364–7.

Boltze KH, Kreisfeld H. On the chemistry of etofenamate, a novel anti-inflammatory agent from the series of N-arylanthranilic acid derivatives [Zur chemie von etofenamat, einem antiphlogistikum aus der klasse der N-arylanthranilsaurederivate]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1977;27:1300–12.

Rechziegler H. Percutaneous treatment with nonsteroid antiinflammatory agents [Perkutane therapie mit nicht-steroidalen antiphlogistika]. Therapiewoche. 1986;36:4674–83.

Rechziegler H, Bernuth VK. Local antiinflammatory treatment with etofenamate: a multicenter study [Lokale antiphlogistische therapie mit etofenamat: eine multizentrische prufung]. Therapiewoche. 1986;36:5347–51.

Fruchtmann R, Krupka U, Pelster B. Inhibition of lipoxygenase and cyclo-oxygenase pathway in the arachidonic acid metabolism by etofenamate [Hemmung des lipoxygenase- und cyclooxygenaseweges im arachidonsäure-metabolismus durch etofenamat]. Akt Rheumatol. 1984;9:165–73.

Etofenamate gel (Reumon® gel): summary of product characteristics. https://app7.infarmed.pt/infomed/detalhes.php?med_id=7509&dci=&nome_comer=cmV1bW9u&dosagem=&cnpem=&chnm=&forma_farmac=&atc=&disp=&estado_aim=&pesquisa_titular=&cft=&grupo_produto=&pagina=1. Accessed 21 Nov 2018.

Etofenamate lotion (Reumon® oção): summary of product characteristics. https://app7.infarmed.pt/infomed/detalhes.php?med_id=7507&dci=&nome_comer=cmV1bW9u&dosagem=&cnpem=&chnm=&forma_farmac=&atc=&disp=&estado_aim=&pesquisa_titular=&cft=&grupo_produto=&pagina=1. Accessed 21 Nov 2018.

Etofenamate cream (Reumon® crème): summary of product characteristics. https://app7.infarmed.pt/infomed/detalhes.php?med_id=7508&dci=&nome_comer=cmV1bW9u&dosagem=&cnpem=&chnm=&forma_farmac=&atc=&disp=&estado_aim=&pesquisa_titular=&cft=&grupo_produto=&pagina=1. Accessed 21 Nov 2018.

Dell HD. Pharmacokinetics of percutaneous therapy [Pharmakokinetik der perkutanen therapie]. Swiss Med. 1989;11:12–20.

Rannou F, Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J. Efficacy and safety of topical NSAIDs in the management of osteoarthritis: evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:S18–21.

Walde HJ. Etofenamate concentrations in intra-articular and peri-articular tissue after percutaneous administration to humans [Konzentration von Etofenamat in intra- und periartikulären Geweben nach perkutaner Applikation beim Menschen]. In: 4th Int. Etofenamat Symposium, 18–21 June 1987, Stresa, pp s91–4.

Schneider H. Local treatment of acute lumbago with etofenamate cream: a comparative study [Lokaltherapie des akuten lumbalsyndroms mit etofenamatcreme: eine vergleichende untersuchung]. Therapiewoche. 1983;33:5809–18.

Miehlke RK, Dornhegge P. Etofenamate for local therapy of activated gonarthroses: results of a single blind test [Etofenamat in der lokaltherapie aktivierter gonarthrosen-ergebnisse einer einfachblindprüfung]. Med Welt. 1985;36:103–6.

Hallmeier B. Efficacy and tolerance of etofenamate and diclofenac in acute sports injuries [Wirksamkeit und verträglichkeit von etofenamat und diclofenac bei sportverletzungen]. Rheuma. 1988;8:183–6.

Rechziegler H. Multicenter trial of etofenamate in 1880 patients with osteoarthritis [Multizentrische prüfung von etofenamat an 1880 patienten mit arthrosis deformans]. Therapiewoche. 1983;33:703–7.

Matsuno S, Sasaki T. Evaluation on usefulness of etofenamate-gel for osteoarthritis of knees—multi-institutional double blind comparative study using indomethacin-gel as reference drug. J Med Pharm Sci. 1983;9:349–67.

Nagaya I, Niwa S. Randomized control clinical trial of etofenamate ointment in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Med Pharm. 1982;8:1549–82.

Ascher R, Schlemmer H, Blümel G, Lechner F. The efficacy of etofenamate in minor sports injuries to knee and ankle joints [Zur wirksamkeit von etofenamat bei leichten sportverletzungen an knie- und sprunggelen]. Fortschr Med. 1982;37:1729–34.

Billigmann P, Pelster B. Placebo-controlled double-blind study of etofenamate gel (Rheumon® gel) in combination with ultraphonophoresis in sports injuries [Plazebokontrollierte doppelblindstudie von etofenamat-gel (Rheumon® gel) in kombination mit ultraphonophorese bei sportverletzungen]. Praktische Traumatol Sportmed. 1992;2:72–7.

Diebschlag W, Nocker W, Bullingham R. A double-blind study of the efficacy of topical ketorolac tromethamine gel in the treatment of ankle sprain, in comparison to placebo and etofenamate. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:82–9.

Matucci-Cerinic M, Casini A. Ketoprofen vs etofenamate in a controlled double-blind study: evidence of topical effectiveness in soft tissue rheumatic pain. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1988;8:157–60.

Seissiger L, Wallner H. Traumon gel in blunt trauma: a comparative study with distorsions and contusions [Traumon® Gel bei stumpfen traumen: eine vergleichende studie bei distorsionen und kontusionen]. Therapiewoche. 1984;34:5045–59.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465–74.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoarthritis: care and management. Clinical guideline [CG177]. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177. Accessed 21 Nov 2018.

Vanderstraeten G, Schuermans P. Study on the effect of etofenamate 10% cream in comparison with an oral NSAID in strains and sprains due to sports injuries. Acta Belg Med Phys. 1990;13:139–41.

Albert G. Experience with etofenamate in combination with ultraphonophoresis [Erfahrungen mil etofenamat in kombination mil ultraphonophorese]. Kassenarzt. 1965;26:30–2.

Plum H. How effective is physical therapy? [Wie elfektiv isl die physikalische therapie?]. TW Sport Medizin. 1990;1:3–12.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Bial. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

We would like to thank Simone Tait of Springer Healthcare Communications who edited the manuscript before submission. This medical writing assistance was funded by Bial.

Disclosures

Daniela Marinho works for Bial, the company that commercialises Reumon Gel, Reumon Creme and Reumon Loção. Anabela Pereira has received speaker's fees from Bial.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12445385.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marinho, O.D.S., Pereira, A. Clinical Efficacy and Safety Profile of Topical Etofenamate in the Treatment of Patients with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Pain Ther 9, 393–410 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00177-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00177-1