Abstract

Introduction

Advance directives (AD) play a central role in end-of-life treatments, intensive care, and palliative care. However, little is known about the experiences of healthcare professionals with ADs. This study reports on palliative care professionals’ views on advance directives (AD).

Methods

A questionnaire was handed out to attendants of a palliative care symposium.

Results

Complete answers were obtained from 126 physicians and 276 nurses. Almost all physicians and nurses had treated patients with an AD, and the majority more than 10 patients. The most frequent refusal by the patients was resuscitation (87.8%) followed by intensive care (79.1%), artificial ventilation, and nutrition. The most frequent wish was pain therapy (92.3%) followed by allowing the natural course of the illness (64.4%). The wish for hospice treatment (44.8%) or spiritual care (39.3%) was less frequent.

Discussion

The results hint at fears and deficits in the care of patients at the end of life. Often the quality of life and not the quantity of days remaining is in the center of a patient’s will and points to the growing importance of palliative care.

Conclusion

ADs are well established among palliative care professionals and regarded as helpful for patients at the end of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the light of an ageing society and medical advancement, patient self-determination at the end of life is of crucial importance. This is illustrated by numerous advanced care planning initiatives [1, 2] taking a comprehensive approach enabling patients to make sure their wishes at the end of life are respected and implemented. In Germany advanced care planning is still a rather new concept [3]. Since 2009 advance directives (ADs) have been regulated by law in the German Civil Code: This did not mean a change in the existing legal situation but was supposed to clarify and strengthen the position of ADs and affirm the existing jurisdiction [4]. While this legislation was welcomed because it provided legal certainty, it is also criticized because it might undermine the importance of the interpersonal relationship between physicians and patients and the significance of open verbal communication at the end of life, leaving the decision-making to the patient alone in a time long before the actual situation [5].

A recent representative study in Germany underlined that the majority of the respondents wanted to make use of an AD to define their will in case they could not speak for themselves [6]. Yet little is known about those specialists caring exclusively for patients at the end of live, palliative care specialists. Their experiences with and opinions about ADs may help to improve future templates and hint at the needs but have not been investigated. Thus a study among physicians and nurses interested in the field of palliative care was performed at a palliative care conference.

Methods

An anonymous questionnaire was handed out to all the participants of a palliative care conference in 2014. Attendants were physicians and nurses. It is the third in a series of surveys on attitudes concerning end-of-life care among professionals interested in the field of palliative care [7,8,9].

The first part of the questionnaire included personal data (gender, age, occupation, and special qualification in palliative care or pain medicine). The second part of the questionnaire consisted of nine questions regarding ADs. The questions were adapted from an established Austrian study and modified according to the legal situation in Germany [10]. The nurses and physicians were asked whether they had treated patients with ADs before and if so how many times. Additionally the questionnaire asked about how the professionals found out about the patient’s AD. In order to specify the content of the AD, the questionnaire asked which treatments the patients refused and which treatments they explicitly wished for. Furthermore it explored problems professionals had experienced in handling the AD and whether they found ADs helpful. Concerning the change in German law on ADs, one question pointed to a possible effect of the law on the professionals’ opinion. Finally the professionals were asked whether they had prepared an AD themselves. Possible answers were “yes”, “no”, and “I don’t know”.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The significance level was set to p ≤ 0.05. Chi square and exact Fisher tests were used to analyze bivariate relationships.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee of ethics of the Ruhr University Bochum (Reg. no. 4502-12) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), as revised in 2013. All respondents were informed about the study and the approval. They gave their consent by answering the questionnaire. Written consent was not possible, because then the anonymity of the respondents would have been violated.

Results

A total of 402 eligible questionnaires were returned, 126 by physicians and 276 by nurses (see Table 1). The total response rate was 56%.

Almost all physicians (96.8%) had treated a patient with an AD; among the nurses the proportion was 94.6% (Table 2). The majority of the respondents had treated more than 10 patients with an AD (83.3% of the physicians and 70.6% of the nurses).

The majority of physicians and nurses actively asked patients and relatives about ADs (80.2% among the physicians and 72.8% of the nurses) and 61.2% of the respondents said patients reported their AD spontaneously. In 62.2% of the cases relatives told the professional about the patient’s AD.

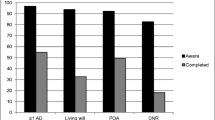

The majority of patients refused intensive care, resuscitation, artificial ventilation, and nutrition. Only 34.6% of the patients refused the provision of fluids.

Nearly all patients wished for pain therapy (92.3%) and allowing the natural course of the disease (64.4%). Hospice care as a wish was mentioned less often in ADs (44.8%). The same holds true for disclosure of prognosis (42.5%). Nondisclosure of negative aspects was requested only rarely (7.3%). Spiritual support was requested in 39.3% of the ADs.

Only few physicians (6.3%) reported having had problems in implementing the AD because of a conflict with their own values; this was true for 4.0% of the nurses. Conflicts in the team occurred in 15.9% among the physicians and 14.1% among the nurses. Furthermore 39.7% of the physicians mentioned conflicts with the relatives of the patient; among the nurses this proportion was 33.7%. The majority of physicians and nurses found ADs helpful (81.7% among the physicians, 83.0% among the nurses).

Physicians and nurses indicated having filled out an AD themselves in 50.8% and 50.0% of the cases, respectively.

The change in the law regarding ADs affected the attitude of 22.2% of the physicians and 22.8% of the nurses; 3.2% of the physicians and 16.7% of the nurses chose “I don’t know”, p ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

Our results suggest that ADs are well established in a palliative care setting with over 90% of the respondents having treated patients with an AD before; in the majority of cases, this was more than ten patients with an AD. These figures are higher than those reported by Schaden et al. from intensive care physicians [10] and meet with expectations of the patients [11].

In line with previous studies, the broad majority of the professionals asked found ADs helpful in knowing their patient’s will and ensuring the patients receive the care they really want [12, 13]. However, the enactment of the law did not have an effect on the physicians’ and nurses’ opinion, which could be seen as in accordance with the clarifying character of the legislation.

ADs are accepted as a meaningful measure to safeguard patients’ wishes. This is in line with recent findings among the German population regarding ADs [14]: 94% of the people asked were aware of the possibility to write an AD. But only 58% of the respondents aged 45–59 years planned to write an AD in the future, while merely 27% had already done so [14]. Not surprisingly, the acceptance of ADs in health professionals is markedly greater with more than half of them having an AD. This is four times greater than recent figures reporting that only 11% of the residents of a nursing home indicated having an AD [15]. This is particularly remarkable since the mean age of the respondents was 86 years, an age when death is statistically quite near [15]. However, there are barriers against completing an AD resulting in a limited distribution among patients and the population as indicated by a recent study [16].

Similar to our study, Sommer et al. highlighted problems regarding the compliance with ADs: in over 60% of the cases the existence of the AD was not documented, so that in case of an emergency the staff responsible would not know about it [15]. In our study only about 60% of the respondents said that patients and the next of kin mentioned any AD spontaneously. This is a common problem [17, 18]. In most cases it is the families and friends that know about the wishes of the patients but not the professionals caring for them in the acute situation; this means that essential information is often not passed on [17, 19]. In a study among the general population of Belgium, only 4.4% of the respondents had spoken to their physician about their preferences at the end of life [20]. The majority of the health professionals in our study actively asked about the existence of an AD, thus emphasizing their awareness of the problems in communicating advance wills. This holds true for physicians and nurses. In a US ICU it was the nurses that asked about the existence of an AD significantly more often than the physicians [21]. Furthermore nurses were found to carefully read the living will of the patients more often than physicians [21]. These differences could not be found in our results, demonstrating higher awareness in professionals in the field of hospice and palliative care. This is known from other studies, i.e., different specialties have different attitudes towards their role in advance care planning: comparing cardiologists and oncologists—both caring for patients in danger of dying in the near future—it is the oncologists that are more willing to get involved in advance care planning discussions [22].

Our results underline the importance of the involvement of relatives in end-of-life decisions because in 62.2% of cases it was the relatives that told the professionals about the existence of the AD. Studies have shown the importance of relatives in surrogate decision-making which occurs in almost half of the cases of older hospitalized patients [23, 24]. The nomination of a person to ensure alternative ways of self-determination has been described as essential in end of life [16]. However, the involvement of the relatives also proved the highest potential for conflict in our results. This has been subject to studies in the past [25, 26]. Potential for conflict arises from the fact that not all surrogates have actually spoken to the patients about their end-of-life preferences, leading to higher uncertainty when it comes to making a decision for the patient [25, 26]. Nevertheless choosing a surrogate decision-maker rather than writing an AD is a common choice [19].

Furthermore conflicts among the team were mentioned by about 15% of the respondents both among the physicians and nurses. Palliative care is an interdisciplinary concept, thus emphasizing the essential role of each discipline involved. Compared to Schaden et al.’s results with conflicts arising mentioned by 48% of the respondents in intensive care, our results show less potential for conflict in palliative care [10]. Deviating views regarding the decision-making process at the end of life have been reported among physicians and nurses [27, 28]. One reason for varying perceptions regarding this measure might be that nurses are traditionally closer to the wishes and needs of the patients at the end of life [29]. Only a minority of the respondents in our study had problems with the AD based on their own values. This is in line with the development from a paternalistic approach towards shared decision-making in medicine [30]. Nevertheless ADs are still sometimes ignored and treatment decisions are made by the physicians [31]. The greatest problems might arise from ADs not being clear enough or too focused on specific measures such as dialysis or resuscitation. Thus there is vast room for interpretation or unknown wishes besides certain (mechanical) measures.

ADs have been criticized in the past with questions arising regarding their ability to safeguard the patients’ wishes [18, 32,33,34]. Furthermore patients are assumed to not have enough medical knowledge to make complex decisions regarding the end of their life [35]. Bearing this in mind it is particularly problematic that discussions about end-of-life decision often take place at a late stage of the disease of the patient which some patients feel is too late to make this kind of complex advance decision [21, 36, 37]. This is where various initiatives such as advance care planning come into play, also emphasizing the role of the general practitioner in acknowledging the patient’s wishes at an early stage of the disease [3]. As many physicians feel uncomfortable initiating discussion about end-of-life measures, these initiatives become even more important [38,39,40,41].

The majority of the respondents in our study reported that patients refuse intensive care measures, resuscitation, ventilation, and nutrition. In the light of medical advancement this finding is not surprising. However, when discussing resuscitation with patients and family members this measure is often mistaken as a “choice between life and death”, posing a high moral burden particularly for the surrogate decision-maker [42]. Advance care planning which is initiated at an early stage of the disease can act as a measure to facilitate making these decisions [43]. Another advantage of this approach is that it takes into account that complex end-of-life decisions take time to emerge and develop [44]. Even an economic effect of advance care planning has been discussed in the literature [45].

Pain therapy was desired in most of the ADs, emphasizing this field of medicine as a crucial part of end-of-life care. Multiple guidelines on pain treatment have emerged since the first edition of the WHO guidelines, and pain has decreased significantly as reason for requests for euthanasia [46]. Hospice care on the other hand was mentioned less often, which might hint at a lack of knowledge about this option or prejudices. This contrasts significantly with recent results with digital advance care planning [47]. However, in our study spiritual care was requested more often, underlining the interdisciplinary holistic approach of palliative care at the end of life.

Nevertheless ADs are still controversial, particularly when it comes to their validity [15]. This is also true for countries that have a liberal legislation on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: In the Netherlands physicians are reluctant to perform euthanasia according to the written advance euthanasia directive in case of severe dementia [48]. In doing so the importance of verbal communication as regards the voluntariness of the wish to die is mentioned [48]. This is also an essential part of advance care planning initiatives [3]. Standardized ADs are often not fit for the specific situation the patient is in, even in the case of progressive disease where likely events can be made out [49]. This has induced discussions regarding regional concepts to bring about qualified advance directives in Germany and on digital forms of advance care planning in the USA to improve the quality and clearness of advance directives [3, 47].

Limitations

The paper reflects only the view of a limited number of specialist physicians and nurses. The results can only highlight some views of palliative healthcare professionals, which do not represent the majority of health professionals caring for dying patients. Additionally, the results only depict the German situation and cannot be compared with other European countries as comparable studies, other than that by Schaden et al., do not exist [10].

Conclusion

ADs are well established in the palliative care setting. They are a means to safeguard the patients’ preferences even when unable to speak for themselves anymore. However, patients have to make use of these instruments. Our findings underline the essential role of pain management at the end of life. The intention to speak about an AD often arises from the professionals rather than the patients. Problems in handling the AD may occur with the relatives of the patient. This hints at the need for early involvement of the family when it comes to end-of-life wishes. Communication among the members of palliative care teams needs to be improved to minimize potential for conflict when implementing the patient’s wishes. Shortcomings of ADs can be identified particularly when it comes to standardized forms that are used without regard to the patients’ specific needs. Advance care planning might be a measure to overcome those deficits.

References

Cook D, Rocker G, Heyland D. Enhancing the quality of end-of-life care in Canada. CMAJ. 2013;185(16):1383–4.

Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345.

In der Schmitten J, Lex K, Mellert C, Rothärmel S, Wegscheider K, Marckmann G. Implementing an advance care planning program in German nursing homes: results of an inter-regionally controlled intervention trial. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(4):50–7.

Wiesing U, Jox RJ, Hessler HJ, Borasio GD. A new law on advance directives in Germany. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(12):779–83.

Maio G. Euthanasia “by the book”. The pitfalls of a legal regulation of patient living wills. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2009;134(31–32):1565–6.

Fegg M, Lehner M, Simon ST, Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Bausewein C. What influences end-of-life decisions? Results of a representative German survey. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58(10):1118–23.

Zenz J, Tryba M, Zenz M. Physician-assisted dying: acceptance by physicians only for patients close to death. Pain Ther. 2014;3:103–12.

Zenz J, Tryba M, Zenz M. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: attitudes of physicians and nurses. Schmerz. 2015;29(2):211–6.

Zenz J, Tryba M, Zenz M. Palliative care professionals’ willingness to perform euthanasia or physician assisted suicide. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:60.

Schaden E, Herczeg P, Hacker S, Schopper A, Krenn CG. The role of advance directives in end-of-life decisions in Austria: survey of intensive care physicians. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11:19.

Justinger C, Richter S, Moussavian MR, Serrano Contreras T, Schilling MK. Advance health care directives as seen by surgical patients. Chirurg. 2009;80(5):455–6, 8–61.

Coleman AM. Physician attitudes toward advanced directives: a literature review of variables impacting on physicians attitude toward advance directives. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(7):696–706.

Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–8.

IFD-Allensbach. Deutlicher Anstieg bei Patientenverfügungen. 2014. http://www.ifd-allensbach.de/uploads/tx_reportsndocs/PD_2014_20.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2016.

Sommer S, Marckmann G, Pentzek M, Wegscheider K, Abholz HH, In der Schmitten J. Advance directives in nursing homes: prevalence, validity, significance, and nursing staff adherence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(37):577–83.

Schröder L, Hommel G, Sahm S. Intricate decision making: ambivalences and barriers when fulfilling an advance directive. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1583–9.

Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):778–87.

Evans N, Bausewein C, Meñaca A, et al. A critical review of advance directives in Germany: attitudes, use and healthcare professionals’ compliance. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):277–88.

Teixeira AA, Hanvey L, Tayler C, et al. What do Canadians think of advanced care planning? Findings from an online opinion poll. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(1):40–7.

De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Houttekier D, Van den Block L, Vander Stichele R, Deliens L. The prevalence in the general population of advance directives on euthanasia and discussion of end-of-life wishes: a nationwide survey. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:71.

Westphal DM, McKee SA. End-of-life decision making in the intensive care unit: physician and nurse perspectives. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(3):222–8.

Chandar M, Brockstein B, Zunamon A, et al. Perspectives of health-care providers toward advance care planning in patients with advanced cancer and congestive heart failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016. doi:10.1177/1049909116636614

Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, et al. Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):370–7.

Torke AM, Siegler M, Abalos A, Moloney RM, Alexander GC. Physicians’ experience with surrogate decision making for hospitalized adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1023–8.

Abbott KH, Sago JG, Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Tulsky JA. Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(1):197–201.

Gutierrez KM. Advance directives in an intensive care unit: experiences and recommendations of critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2012;35(4):396–409.

Sprung CL, Woodcock T, Sjokvist P, et al. Reasons, considerations, difficulties and documentation of end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units: the ETHICUS Study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):271–7.

Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B, et al. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(10):1310–5.

Berghs M, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C. The complexity of nurses’ attitudes toward euthanasia: a review of the literature. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(8):441–6.

Erbguth F. Between patient autonomy and the ethics of care: difficult end-of-life decision-making in intensive care. Anaesthesist. 2012;61(6):521–8.

Hardin SB, Yusufaly YA. Difficult end-of-life treatment decisions: do other factors trump advance directives? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(14):1531–3.

Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30–42.

Levi BH, Green MJ. Too soon to give up: re-examining the value of advance directives. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10(4):3–22.

Bonner S, Tremlett M, Bell D. Are advance directives legally binding or simply the starting point for discussion on patients’ best interests? BMJ. 2009;339:b4667.

Lang-Welzenbach M, Rödel C, Vollmann J. Patientenverfügung in der Radioonkologie: einstellung von Patienten. Ärzten und Pflegepersonal Ethik Med. 2008;4:300–12.

Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(3):204–10.

Kong BH, An HJ, Kim HS, et al. Experience of advance directives in a hospice center. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(2):151–4.

Tulsky JA, Chesney MA, Lo B. See one, do one, teach one? House staff experience discussing do-not-resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(12):1285–9.

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, Collier AC. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(11):1690–6.

Deep KS, Griffith CH, Wilson JF. Communication and decision making about life-sustaining treatment: examining the experiences of resident physicians and seriously-ill hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1877–82.

Horlait M, Chambaere K, Pardon K, Deliens L, Van Belle S. What are the barriers faced by medical oncologists in initiating discussion of palliative care? A qualitative study in Flanders, Belgium. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(9):3873–81.

Eliott J, Olver I. Choosing between life and death: patient and family perceptions of the decision not to resuscitate the terminally ill cancer patient. Bioethics. 2008;22(3):179–89.

Epstein AS, Shuk E, O’Reilly EM, Gary KA, Volandes AE. ‘We have to discuss it’: cancer patients’ advance care planning impressions following educational information about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Psychooncology. 2015;24(12):1767–73.

Prendergast TJ. Advance care planning: pitfalls, progress, promise. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2 Suppl):N34–9.

Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M. The economic evidence for advance care planning: systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med. 2015;29(10):869–84.

Marquet RL, Bartelds A, Visser GJ, Spreeuwenberg P, Peters L. Twenty five years of requests for euthanasia and physician assisted suicide in Dutch general practice: trend analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):201–2.

Fine RL, Yang Z, Spivey C, Boardman B, Courtney M. Early experience with digital advance care planning and directives, a novel consumer-driven program. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29(3):263–7.

Kouwenhoven PS, Raijmakers NJ, van Delden JJ, et al. Opinions about euthanasia and advanced dementia: a qualitative study among Dutch physicians and members of the general public. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:7.

Nauck F, Becker M, King C, Radbruch L, Voltz R, Jaspers B. To what extent are the wishes of a signatory reflected in their advance directive: a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:52.

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

M. Zenz is chairman of the Ethics Committee of the Ruhr-University Bochum. J. Zenz has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee of ethics of the Ruhr University Bochum (Reg. no. 4502-12) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), as revised in 2013. All respondents were informed about the study and the approval. They gave their consent by answering the questionnaire. Written consent was not possible, because then the anonymity of the respondents would have been violated.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request. The same is true for the original German version of the questionnaire.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/C427F0600B812386.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zenz, J., Zenz, M. Survey on German Palliative Care Specialists’ Experiences with Advance Directives. Pain Ther 6, 17–28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-016-0063-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-016-0063-0