Abstract

We report the case of an acute cerebellitis following COVID-19 in 32-year-old man who presented with a life-threatening critical cerebellar syndrome contrasting with normal paraclinical findings. Despite this fulminant critical presentation, the patient fully recovered in 37 days after early treatment with high-dose steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins. This case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of acute cerebellitis following COVID-19, despite normal laboratory, imaging and electroencephalography findings and the importance to start appropriate treatment as soon as possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This case study details acute cerebellitis following SARS-CoV-2 infection in an immunocompetent adult. |

There was an alarming clinical presentation challenged by normal paraclinical findings. |

This shows that it is necessary to start the appropriate treatment (steroids, IgIV) as soon as possible. |

Introduction

Neurological damage in the acute phase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is well described, with a wide range of symptoms such as olfactory and gustatory disorders, headache or dizziness [1, 2]. Approximately 35% of the patients are neurologically impaired [3, 4], and this percentage further increases in case of severe infection under intensive care [5, 6]. Onset of neurological disorders may also appear several weeks after the acute phase and could be immune-mediated [7]. We report herein the case of an acute cerebellitis (AC), probably immune-mediated, following SARS-CoV-2 infection in an immunocompetent adult patient.

The patient’s written consent was obtained. We made sure to keep participant data confidential and in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments.

Case Presentation

A 32-years-old Caucasian man, with no past medical history, was admitted to the emergency department on 31 October 2023 because of acute dysarthria and gait disorder associated with fever (38.7 °C), without seizures or impaired consciousness or coma (Glasgow Coma Scale score 15), following headache and severe asthenia. Physical examination revealed a cerebellar syndrome, with ataxia, dysarthria and dysmetria. These appeared 2 weeks after a mild respiratory viral infection with similar cases in his family members with suspected coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The patient had no history of drug use or recent vaccination.

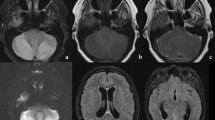

At admission, all routine laboratory findings were in normal ranges, including C-reactive protein (CRP) at 0.14 mg/dL. Two nasopharyngeal COVID-19 real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests performed 2 days apart were weakly positive (E gene cycle threshold at 38.7 and 35.0) which confirmed a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Brain computed tomography angiography and subsequent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were normal (in T1, T2, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery [FLAIR] sequences, diffusion weighted imaging [DWI] and apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC] measurements).

Lumbar puncture (LP) showed clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with normal pressure, minimal pleocytosis (6 white blood cells/mm3, 430 red blood cells/mm3), normal protein level (0.31 g/L), normal glucose and negative direct examination (Table 1). The FilmArray® meningitis/encephalitis panel was negative. An empiric treatment with intravenous (IV) infusions of amoxicillin 12 g daily and aciclovir 15 mg/kg/8 h was started.

On day 3, the cerebellar syndrome worsened, with severe dysarthria and ataxia. A second LP was performed showing correction of pleiocytosis with 2 white blood cells/mm3, increased protein level (0.52 g/L), normal glucose level, and no malignant cells. Electroencephalogram (EEG) on day 3 and MRI with angiography on day 4 were normal. Thus, a post-infectious autoimmune cerebellitis was suspected, regarding the clinical presentation in the context of a recent COVID-19. IV methylprednisolone (1 g/day) was started on day 4. Amoxicillin was stopped after confirmation of negative CSF cultures at 72 h.

On day 7, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) because of swallowing disorders with a Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) score of 36/40. IV immunoglobulins (IgIV) were started at a dose of 0.4 g/kg daily (28 g/day) for 5 days.

On day 8, symptoms were improving. A whole-body [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) was normal. Aciclovir was stopped following negative herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus-specific PCR on follow-up LP, and steroids were also discontinued after 5 days.

On day 9, the patient was discharged from ICU to the neurology department. The only remaining symptom was ataxia, which had already started improving. Brain MRI and EEG follow-up were also normal, with no changes. He was transferred to a rehabilitation centre on day 23 with SARA score of 3/40. When he was fully discharged from hospital on day 30, he only had slight dysphonia with a SARA score of 1/40. On day 37 the patient had fully recovered, including from his dysphonia with a SARA score of 0/40. We did not observe any relapse afterwards, during a 5-month follow-up period.

Discussion

COVID-19-related AC must be suspected in case of acute cerebellar syndrome which appears several days or weeks (9 weeks at most) after SARS-CoV-2 infection [8, 9]. Our patient had initially a critical cerebellar syndrome with life-threatening risk that required critical care. Despite this fulminant critical presentation, the patient fully recovered in 37 days; our main assumption is that the patient have been quickly treated with high doses of steroids (day 4) and IgIV (day 7). This hypothesis is supported by other case reports where late initiation of treatment with steroids or IgIV (i.e. after day 7 of symptoms) affected the kinetics of symptom improvement and may lead to incomplete or delayed recovery [8,9,10].

Our case had an alarming clinical presentation challenged by normal paraclinical findings. Among the 20 patients reported with COVID-19-related cerebellitis in the Plumacker et al. cohort, 32% (6/19) had a normal brain MRI, and 61% (11/18) had no abnormality on CSF analyses [8]. Thus, AC following COVID-19 must be suspected even if laboratory and imaging findings are normal. In case of AC following COVID-19 with CSF pleiocytosis, differential diagnoses as viral or bacterial encephalitis are challenging [8, 9]. These diagnoses must be ruled out by CSF microbiological analysis, but without delaying treatment regarding the risk of neurological sequelae [8]. Since the first case of AC following SARS-CoV-2 infection reported by Fadakar et al. in 2020, several dozen cases have been described [8, 11,12,13,14], and various pathophysiological mechanisms have been described for cerebellum region damage, such as direct virus infection, immune-mediated mechanisms, or damage secondary to hypoxemia [8, 11,12,13]. A systematic review of post-COVID cerebellitis cases reveals a male predilection, indicating a possible gender-related susceptibility [14]. In our case, cerebellar symptoms occurred 2 weeks after COVID-19, and all blood and CSF parameters were normal (including COVID-19 RT-PCR in the CSF and immunological investigations). This can lead one to diagnose a post-viral AC but cannot confirm a viral invasion of the central nervous system. On the other hand, the chronology of events (delayed onset) and the almost immediate response to steroids and immunoglobulins are in favour of an immune-mediated mechanism, but this could not be strictly confirmed because of the lack of antibodies detected in blood and CSF. In other studies, in most cases, high doses of steroids and/or IV immunoglobulins are administered with favourable results [8].

This case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of AC following COVID-19, despite normal laboratory, imaging and EEG findings and the importance to start appropriate treatment as soon as possible.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Chan JL, Murphy KA, Sarna JR. Myoclonus and cerebellar ataxia associated with COVID-19: a case report and systematic review. J Neurol. 2021;268(10):3517–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10458-0.

Harapan BN, Yoo HJ. Neurological symptoms, manifestations, and complications associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). J Neurol. 2021;268(9):3059–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10406-y.

Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):767–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0.

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127.

Liotta EM, Batra A, Clark JR, et al. Frequent neurologic manifestations and encephalopathy-associated morbidity in Covid-19 patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(11):2221–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51210.

Pun BT, Badenes R, La-Calle GH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (COVID-D) a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(3):239–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30552-X.

Zayet S, Klopfenstein T, Kovẚcs R, Stancescu S, Hagenkötter B. Acute cerebral stroke with multiple infarctions and COVID-19, France, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9):2258–60. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2609.201791.

Plumacker F, Lambert N, Maquet P. Immune-mediated cerebellitis following SARS-CoV-2 infection—a case report and review of the literature. J NeuroVirol. 2023;29(4):507–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-023-01163-x.

Fadakar N, Ghaemmaghami S, Masoompour SM, et al. A first case of acute cerebellitis associated with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a case report and literature review. Cerebellum. 2020;19(6):911–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-020-01177-9.

Werner J, Reichen I, Huber M, Abela IA, Weller M, Jelcic I. Subacute cerebellar ataxia following respiratory symptoms of COVID-19: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05987-y.

Malayala SV, Jaidev P, Vanaparthy R, Jolly TS. Acute COVID-19 cerebellitis: a rare neurological manifestation of COVID-19 infectio. Cureus. 2021;13(10):e18505. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18505.

Nepal G, Rehrig JH, Shrestha GS, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2020;24:421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03121-z.

Watanabe T, Kakinuma Y, Watanabe K, Kinno R. Acute cerebellitis following COVID-19 infection associated with autoantibodies to glutamate receptors. J Neurovirol. 2023;29(6):731–3.

Najdaghi S, Narimani Davani D, Hashemian M, Ebrahimi N. Cerebellitis following COVID-19 infection. Heliyon. 2024;10(14):e34497.

Funding

Not applicable for the research. The journal’s publication fees were funded by the clinical research unit of the Nord-Franche-Comté Hospital (HNFC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Timothée Klopfenstein; Investigation, Timothée Klopfenstein; Methodology, Timothée Klopfenstein; Resources, Samantha Poloni, Abdoulaye Hamani, Pauline Escoffier, and Valentine Kassis; Supervision, Timothée Klopfenstein. and Souheil Zayet; Validation, Timothée Klopfenstein, Souheil Zayet, Beate Hagenkotter, and Vincent Gendrin; Writing—original draft, Samantha Poloni; Writing—review and editing, Timothée Klopfenstein, Souheil Zayet, Beate Hagenkotter, and Vincent Gendrin.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All named authors confirm that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

The patient’s written consent was obtained. We made sure to keep participant data confidential and in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Poloni, S., Hamani, A., Kassis, V. et al. Acute Cerebellitis Following COVID-19: Alarming Clinical Presentation Challenged by Normal Paraclinical Findings. Infect Dis Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-01048-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-01048-4