Abstract

Introduction

Fungal prosthetic joint infections comprise less than 1% of prosthetic joint infections. Thus, little is known regarding optimal management. This study aims to characterize the microbiology, surgical and medical management, and outcomes for these complex infections. The objectives of this study were to assess the impact of surgical approach, antifungal treatment, fungal species, and time to onset of infection from initial surgery on patient outcomes.

Methods

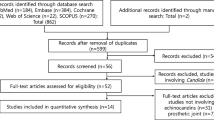

A retrospective record review over 12 years was performed in two health systems that included patients with a deep culture positive for a fungal isolate and the presence of a prosthetic joint. A literature review was performed using the same inclusion criteria. A total of 289 cases were identified and analyzed.

Results

Candida was the most common isolate, and a two-stage revision was the most commonly employed surgical modality. The type of surgical intervention had a statistically significant relationship with outcome (P = 0.022).

Conclusions

Two-stage revision with extended antifungal therapy is preferred in these infections due to higher rates of positive outcomes.

Plain Language Summary

Prosthetic joint infections may be caused by fungal organisms, but as this is rare, it is not known how to best treat these infections. This study explores the types of fungal organisms involved in these infections, options for surgical and medical treatment, and patient outcomes. We analyzed records over 12 years at two health systems and the currently published works on this topic. A total of 289 records were analyzed. The fungus Candida was the most common infectious cause, and a two-stage revision surgery was most commonly performed. We found that the type of surgical intervention was correlated with the patient outcome and that two-stage revision with a long course of antifungal medications is preferred in these infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out the study? |

With increasing arthroplasties, more periprosthetic deep infections are being seen, but no standardized treatment protocols exist. |

What was learned from the study? |

Very few infections resolve without combined surgical and medical management. |

Debridement and Girdlestone procedures underperform when compared to one-stage and two-stage revision. |

Most cases are treated with 3–6 months of antifungal therapy. Lifelong fungal suppression may be used if surgery is not an option. |

Introduction

The 2022 American Joint Replacement Registry reported 2,550,232 primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasties between 2012 and 2021 [1]. The number of knee and hip arthroplasties has risen significantly in the United States and is projected to continue to increase [2]. Concurrently, an increasing number of periprosthetic deep infections have been diagnosed, with a nearly two-fold increase between 1990 and 2004 [2]. Most infections are caused by Gram-positive bacteria, with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis being the most commonly recovered isolates [3].

Fungal prosthetic joint infection represents less than 1% of infections but poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to orthopedists and infectious disease physicians [4]. Often, these patients are in states of immunosuppression, possess other risk factors such as diabetes, or have had a prior revision arthroplasty [5]. The most effective treatment for fungal prosthetic joint infections remains unclear. Most cases are treated with two-stage revisions combined with systemic antifungal medications.

The most extensive studies of total hip and knee arthroplasty fungal infections have included 93 and 132 patients, respectively [6]. More data are required on the treatment and outcomes of patients affected by fungal prosthetic joint infection. The purpose of this study was to retrospectively compare the outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections involving different fungal isolates and modes of medical and surgical management in our institutions while evaluating available data on reported cases in the literature. The objectives were to assess the relationship between fungal species and outcome, fungal type and outcome, surgical repair and outcome, onset of infection from initial surgery and outcome, and monomicrobial and polymicrobial infections and outcome.

Methods

A retrospective record review was conducted from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2018, of patients 18 years and older admitted to The University of Toledo Medical Center and the ProMedica Health System in Toledo, Ohio, with fungal prosthetic joint infections. This study was approved by both IRB boards and patient consent was waived due to the study involving retrospective data without active patient involvement. Inclusion criteria for the chart review included the presence of a prosthetic joint with at least two deep cultures for the same fungal organism or one positive bone culture for a fungal organism with or without a draining sinus tract. At least two deep cultures were selected to minimize the inclusion of patients with culture contamination. Standard laboratory techniques were used for the requested cultures. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or if, on record review, the infection was not associated with the orthopedic implant. Demographic data, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell count (WBC), presence of concurrent bacterial infection, surgical management, antimicrobial management, episodes of relapse, and treatment course were reviewed. Relapse was defined as requiring further surgical management or antimicrobial therapy after the initial treatment course.

A PubMed and Embase search of the English-language literature from January 1, 1980, to January 1, 2023, was additionally performed by reviewing pertinent references for cases meeting the inclusion criteria. Search terms included an extensive list of fungal species (see Table S1 in Appendix A for further information). Patients that met the following inclusion criteria were included: presence of prosthetic joint and positive deep culture for fungus (see Table S2 in Appendix A for further information). Cases were excluded if there were insufficient demographic data, including age, gender, site of the prosthesis, and culture results.

Data were compiled into an Excel spreadsheet, and descriptive statistics were collected. SPSS Statistics was used for statistical analysis to compare data. Crosstabulations were made for fungal species and outcome, fungal type (mold, yeast, dimorphic) and outcome, antifungal class and outcome, surgical repair and outcome, and time to onset of infection and outcome. Pearson Chi-square tests were performed for the above crosstabulations with a significance value of P < 0.05. ANOVA was used to test for significant differences in outcomes across age groups.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Toledo and ProMedica Health Systems. Patient consent was waived, as this was a retrospective review and it was not feasible to contact all patients.

Results

Retrospective Record Review

Eighteen patients fit the inclusion criteria during this period in the retrospective record review from the University of Toledo and the ProMedica System in Toledo, Ohio. The average age at the time of infection was 61.9 years; 55.6% were female; seven patients were Caucasian, two were African American, and the race of the remaining nine patients was unknown. The average BMI was 32.1 kg/m2. Six patients had diabetes mellitus, and six were immunosuppressed for reasons including prior transplant on immunosuppressive medications, cancer on chemotherapy and/or radiation, and immunosuppressive medications for rheumatologic conditions. Fifty percent had an infected hip, and the other 50% had an infected knee. Twelve (66.7%) had at least one prior revision. The average ESR was 47.8 mm/h, CRP was 11.9 mg/dl, and WBC was 9.4 (× 109/l) (Table 1)

Consistent with previously reported literature, 12 of 18 patients had a history of prior revision. Twelve patients presented with a painful joint, eight with drainage, and one with joint dehiscence. Fungal culture was positive for Candida species in all cases. Candida albicans was isolated in 65% of cases, Candida parapsilosis was isolated in 23%, and Candida glabrata and Candida dublinensis were each isolated in 6% of cases. Additionally, one patient with prosthetic joint infection of the knee was noted to have positive cultures for Trichophoron inkin and C. albicans. Thirteen of the 18 patients identified had a co-infecting bacterial organism identified on culture, with Staphylococcus aureus being the predominantly isolated organism. Other frequently isolated organisms identified were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Enterococcus species, and Serratia species (Table 2).

Among the 18 affected patients, 15 had known outcomes. Debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR), one-stage exchange, two-stage exchange, Girdlestone procedure, and amputation were used as treatment modalities (Fig. 1). Of the three patients that received DAIR, two were noted to have relapse of infection, and one patient died. Of the seven patients receiving two-stage exchange, three were noted with cure (defined as the absence of infection at > 1-year follow-up), three with relapse, and one with an unknown outcome. Of the other treatment modalities, one patient with a one-stage exchange, one patient with amputation, and one patient that received the Girdlestone procedure were cured. The remaining patient, who received a stage one revision as destination therapy, experienced a relapse of the fungal PJI.

Of the 15 patients in whom antifungal therapy was known, nine were treated with fluconazole, three were treated with micafungin, and two were treated with both modalities at some point during their fungal prosthetic joint infection treatment. Of the 14 patients in which the duration of therapy was known, eight received a 6-week course of therapy. Two received an 8-week course of therapy or longer, while three received a 2-week course of shorter. One received no antifungal therapy (Table 3).

Review of the Literature

Demographics

A literature review revealed 271 cases reported between 1980 and 2023 that met inclusion criteria [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117]. Patients’ age at the time of infection ranged from 31 to 89, with a mean of 66.7 ± 11.7. A total of 146 were female (54.3%); 106 (39.1%) of the reviewed cases reported comorbidities of diabetes mellitus (29.1%) or immunosuppression (17.0%). Patient race was not consistently reported.

The number of previous revisions or previous infections was not consistently reported. Previous revision history was reported in 49 cases, with reasoning for revision provided in 27 cases. Infection was cited as the reason in ten of these cases. One case had a previous fungal prosthetic joint infection caused by Candida species. The other cited reasoning for prior revisions included pain, aseptic loosening, and periprosthetic fractures.

Diagnostic Findings

Regarding the prosthetic joint, 43.5% of patients had an affected hip, and 53.8% had an affected knee. Other infected joints included five shoulders and one finger [16, 18, 53, 55, 62, 115]. On presentation, 53.1% of patients presented with a painful joint; 13.3% and 16.5% had dehiscence and drainage, respectively. Time to onset of infection was classified into: early (less than 3 months after), delayed (3–24 months after), and late (more than 24 months after). Time to onset was reported in 134 cases: 23 cases presented with early infection, 53 with delayed infection, and 58 with late infection.

The average CRP and ESR were 28.9 mg/l and 58.1 mm/h, respectively. The average WBC was 10.3 × 109/l. Among the fungal isolates, 13% were yeasts, 5% were molds, and a significant majority, 82%, were dimorphics. Also, 87% of cases were Candida species; 102 cases were C. albicans, 72 were C. parapsilosis, 25 were C. glabrata. Of the remainder, six cases were Histoplasma species, and 62 cases were other fungal species, including additional Candida species.

Sixty-nine (25.5%) cases presented with a bacterial co-infection. The bacterial species were predominantly coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species (35.2%), followed closely by Staphylococcus aureus (31.5%).

Treatment and Surgical Management

Most (69.4%) cases were treated with an azole. Figure 2 describes the antifungals used in the treatment of these cases. Fifty-three cases were treated with a combination of antifungals, with the combination of azoles and echinocandins being the most common. Treatment duration varied from < 6 weeks to > 1 year (Fig. 3). Eight patients were treated with lifelong antifungal suppression with fluconazole. The rationale for lifelong suppression included the presence of mold (2), immunosuppression (3), and refusal of surgery (3).

Surgical repair in combination with antifungal therapy was performed in 86.7% of cases. Different types of surgical management included debridement, one-stage exchange, two-stage exchange, Girdlestone procedure, and three-stage revision. The two-stage exchange was the most common (33%), followed by one-stage exchanges (25%) (Fig. 4).

Combined Data from Retrospective Chart Review and Literature Review

Outcomes

Identified outcomes included complete recovery, reoccurrence not requiring repeat surgery, reoccurrence requiring repeat surgery, death secondary to the infection, and others (loss to follow-up, death from a secondary cause). Outcomes are as follows: 208 cases had recovery, 22 had a fungal prosthetic joint infection recurrence, 43 had recurrence requiring revision surgery, six died, and 15 had unreported or unknown outcomes. The observed outcomes are described in Fig. 5.

The continuous predictor variable of age was compared against the outcomes using ANOVA testing and did not identify a statistically significant difference (P = 0.570). When the outcomes for each surgical approach were compared using the Pearson Chi-square test, there was a statistically significant difference between the type of surgical approach and patient outcome (P = 0.022). An increase in negative outcomes (reoccurrence, need for revision, and death) in patients undergoing a Girdlestone procedure was noted. Sixty percent of patients who underwent the Girdlestone procedure had a negative outcome, compared to 15% and 18% for one and two-stage exchanges, respectively. There was no identified significance for the fungal species (P = 0.512), class of fungal infection (P = 0.344), and antifungal used (P = 0.728) when compared against outcomes. There was a marginal relationship between the time to onset of infection and outcome (P = 0.063).

Discussion

With increasing arthroplasties and periprosthetic deep infections, determining appropriate treatment and optimal surgical management is vital to preventing poor outcomes. Currently, no standardized guidelines exist for managing fungal prosthetic joint infection.

Patients most at risk for fungal prosthetic joint infections have comorbidities that delay wound healing and immune response, such as diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and kidney disease [5]. One previous study reported prior revision surgery and age > 65 as independent risk factors, though the current study did not reproduce those findings [118]. This may be because many case reports did not report demographic data or comorbidities for the patients presented.

Infections are classified based on time of development in relation to initial surgery: early (less than 3 months after), delayed (3–24 months after), and late (more than 24 months after) [119]. Presenting symptoms vary based on the time of presentation. In our study, over half of the patients were reported to present with an acutely painful joint (53.1%). Early infections often present with acute onset pain, effusion, erythema, and warmth. Delayed infections may present with more subtle signs, such as implant loosening and persistent pain. Inflammatory markers may aid diagnosis, but these are insufficient in and of themselves to determine the presence or absence of infection. Periprosthetic and intraoperative cultures are essential in determining the causative organism.

Very few of the presented cases resulted in a cure in the absence of surgery, demonstrating the importance of surgery in management. Surgical approaches include DAIR, one-stage exchange, stage one destination, two-stage exchange, Girdlestone procedure, three-stage revision, amputation, and arthrodesis. There was a significant difference in the type of surgical approach and patient outcome. Our study found that two-stage exchange was performed in a third of the presented cases, with 79% undergoing full recovery without any reported recurrence of infection. Previous reviews have reported two-stage exchange as the gold standard [5, 118]. Over half of the patients who underwent the Girdlestone procedure had a negative outcome. However, it must be noted that the Girdlestone procedure is often done in prior failed surgical reimplantation or in non-ambulatory patients, who are at higher risk for negative outcomes [120].

Antifungal usage is often determined by species resistance, hospital patterns of resistance, and patient comorbidities. Our study demonstrated azoles as the most common antifungal used, noted in 79% of reported cases, though 22% of cases were treated with a combination of antifungals. Treatment duration varied from < 6 weeks to > 1 year, with 3–6 months being the most common duration. For Candida joint infections, the IDSA currently recommends an azole such as fluconazole for 6 weeks or echinocandin for 2 weeks followed by an azole for at least 4 weeks as well as device removal for infection involving a prosthetic [121]. Chronic suppression with fluconazole is recommended if the device cannot be removed. This approach was used in 8 of the presented cases who either declined surgery or were poor surgical candidates. These patients did not have reported recurrence.

Our study is retrospective, so limitations of this study include a lack of some pertinent demographic, clinical, and diagnostic data. When considering polymicrobial and monomicrobial infections, a potential confounding variable is the receipt of broad-spectrum antimicrobials before and during surgical intervention. This variable could not be analyzed due to a lack of reporting in the literature, but it should be considered in future research. Additional confounding variables include the differences in the performance of laboratory personnel that may result in under and overreporting of fungal PJI and, additionally, orthopedic surgery practices may result in differences in the rate of fungal PJI among different centers.

This study identified a marginal relationship between the time to onset of infection and the patient outcome. However, this was limited by a low frequency of reporting of the time between initial prosthetic joint replacement and identification of infection. This relationship should continue to be explored in future research. As this study covers an extensive time frame from 1980 to 2023, it should be noted that medical practice and diagnostics have shifted accordingly. A recent study by Gonzalez et al. reviewed 225 cases of prosthetic joint infections emphasizing surgical approaches to treating fungal prosthetic joint infections [6]. The current study expands on this work by adding some case reports excluded in the former study. It includes a specific analysis of the microbiology and antifungal therapy with their relationship to the outcome.

Management of prosthetic fungal joint infections has not been standardized; it has been based on presented cases in the literature and physician experience. All studies discussed in this paper have been retrospective, as performing a randomized clinical trial with either medical or surgical intervention for fungal prosthetic joint infections may not be feasible. Current best practices would support aggressive surgical management, such as a two-stage exchange with prolonged (> 3 months) antifungal therapy directed at the specific pathogen.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hegde V, Stambough JB, Levine BR, Springer BD. Highlights of the 2022 American Joint Replacement Registry annual report. Arthroplast Today. 2023;21: 101137.

Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplast. 2008;23(7):984–91.

Lentino JR. Prosthetic joint infections: bane of orthopedists, challenge for infectious disease specialists. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(9):1157–61.

Azzam K, Parvizi J, Jungkind D, Hanssen A, Fehring T, Springer B, Bozic K, Della Valle C, Pulido L, Barrack R. Microbiological, clinical, and surgical features of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a multi-institutional experience. JBJS. 2009;91(Supplement_6):142–9.

Gross CE, Della Valle CJ, Rex JC, Traven SA, Durante EC. Fungal periprosthetic joint infection: a review of demographics and management. J Arthroplast. 2021;36(5):1758–64.

Gonzalez MR, Bedi ADS, Karczewski D, Lozano-Calderon SA. Treatment and outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of 225 cases. J Arthroplast. 2023;38:2464-2471.e1.

Giovanoulis V, Vasiliadis AV, Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Batailler C, Ferry T, Lustig S. Prosthetic knee joint infection due to Candida lusitaniae: a diagnostic and therapeutic odyssey: a case study. Diagnostics. 2022;12(11):2640.

Williams BT, Hogan C, Damioli L. Two-stage revision total knee arthroplasty for chronic histoplasma capsulatum prosthetic joint infection: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2022;12(3):e22.00155.

Koutserimpas C, Naoum S, Alpantaki K, Raptis K, Dretakis K, Vrioni G, Samonis G. Fungal prosthetic joint infection in revised knee arthroplasty: an orthopaedic surgeon’s nightmare. Diagnostics. 2022;12(7):1606.

Chong YC, Tse TST. A case of Candida parapsilosis periprosthetic joint infection: case report and literature review. J Orthop Trauma Rehabil. 2022;29(1):22104917221075824.

Shah S, Haq S, Antony SJ. Coccidioidomycosis resulting in a prosthetic joint infection in an immunocompetent patient after a total hip arthroplasty: a case report and review of the literature. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2022;22(2): e170322188282.

Lin Y-J, Su T, Yang L, Chen G-X. Mixed bacterial-fungal infection following total hip arthroplasty: a case report. Chin J Traumatol. 2022;25(01):32–6.

Bottagisio M, Bidossi A, Logoluso N, Pellegrini A, De Vecchi E. A spacer infection by Candida albicans secondary to a Staphylococcus capitis prosthetic joint infection: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):416.

Morimoto Y, Yo H, Ohashi H. Two-stage revision using antifungal-loaded cement beads for the treatment of Candida infection following revision total hip arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Sci. 2021;26(3):505–9.

Kurmis AP. Eradicating fungal periprosthetic TKA “super-infection”: review of the contemporary literature and consideration of antibiotic-impregnated dissolving calcium sulfate beads as a novel PJI treatment adjunct. Arthroplast Today. 2021;8:163–70.

Berbari HE, Gurram P, Mahmood M, Deziel PJ, Walker RC, Razonable RR. Prosthetic joint infections due to histoplasma capsulatum: a report of 3 cases. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):225–9.

George JC, Sainulabdeen J, Chittaranjan S, George K, Babu S. Single-stage revision with fluconazole monotherapy in fungal prosthetic knee joint infections. Arthroplast Today. 2021;7:238–41.

Kobayashi T, Lawler E, Samra H, Ford B, Sekar P. Prosthetic finger joint infection due to Aspergillus terreus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa614.

Ciochetto Z, Georgen M, Hadro A, Jurkowski L, Ridolfi K, Wooldridge A, Gundacker N, Haque J. Reactivation of Coccidioides immitisi in a prosthetic knee after initiation of chemotherapy. Case Rep Hematol. 2021;2021:3964465.

Oenning S, Moellenbeck B, Gosheger G, Schmidt-Bräkling T, Schwarze J, Ackmann T, Schneider KN, Theil C. Fungal periprosthetic knee joint infection in a patient with metamizole-induced agranulocytosis. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6(4):726–30.

Frieler S, Yilmaz E, Goodmanson R, Hanusrichter Y, Schildhauer TA, Baecker H. Conversion from knee arthrodesis back to arthroplasty: a particular challenge in combination with fungal periprosthetic joint infection. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6(4):1038–44.

Xin J, Guo QS, Zhang HY, Zhang ZY, Talmy T, Han YZ, Xie Y, Zhong Q, Zhou SR, Li Y. Candidal periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty combined with ipsilateral intertrochanteric fracture: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(21):5401–8.

Saconi ES, de Carvalho VC, de Oliveira PRD, Lima A. Prosthetic joint infection due to Candida species: case series and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(15): e19735.

Vergison L, Schepens A, Liekens K, De Kesel R, Van der Bracht H, Victor J. Periprosthetic joint infection of a total hip arthroplasty with Candida parapsilosis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;69:72–5.

Murata Y, Okabe S, Tamagawa S, Ohnishi H, Sakai A. Candidal prosthetic hip infection in a patient with previous candidal sepsis—a case report. J UOEH. 2020;42(4):327–30.

Bini Viotti J, Corzo-Pedroza M, Gonzales Zamora JA. Prosthetic joint infection caused by Candida lusitaniae: report of a unique case. Acta Clin Belg. 2019;74(4):286–91.

Meiyappan A, Villa JM, Sabesan VJ, Patel PD, Suarez JC. Histoplasma capsulatum periprosthetic knee infection complicated by autoimmune-mediated systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Arthroplast Today. 2019;5(2):135–8.

Pasticci MB, Papalini C, Leli A, Bruno G. Two-stage revision and systemic antifungal therapy of Candida glabrata primary prosthetic hip infection successfully treated: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):151.

Kuner E, Jöckel JA, Orler R, Nüesch R. Periprosthetic knee infection by Mycobacterium bovis and Candida guilliermondii in the context of a zoonosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2019;13(1):54.

Lee YR, Kim HJ, Lee EJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Yoon YK. Prosthetic joint infections caused by Candida species: a systematic review and a case series. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(1):23–33.

Gao Z, Li X, Du Y, Peng Y, Wu W, Zhou Y. Success rate of fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection treated by 2-stage revision and potential risk factors of treatment failure: a retrospective study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5549–57.

Xiang Y, Xuan YY, Li G. Successful treatment for acute prosthetic joint infection due to MRSA and Candida albicans: a case report and literature review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:1133–9.

Sebastian S, Malhotra R, Pande A, Gautam D, Xess I, Dhawan B. Staged reimplantation of a total hip prosthesis after co-infection with Candida tropicalis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus: a case report. Mycopathologia. 2018;183(3):579–84.

Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Velivassakis E, Iliopoulou-Kosmadaki S, Kontakis G, Kofteridis DP. Candida glabrata prosthetic joint infection, successfully treated with anidulafungin: a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2018;61(4):266–9.

Burgo FJ, Mengelle DE, Abraham A, Kremer G, Autorino CM. Periprosthetic fungal infection of a hip caused by Trichosporon inkin. Arthroplast Today. 2018;4(1):24–6.

Bartash R, Guo Y, Pope JB, Levi MH, Szymczak W, Saraiya N, Nori P. Periprosthetic hip joint infection with Aspergillus terreus: a clinical case and a review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2017;18:24–7.

Carrega G, Cavagnaro L, Basso M, Riccio G, Ronca A, Salomone C, Burastero G. Azole-resistant Candida albicans prosthetic joint infection treated with prolonged administration of anidulafungin and two-stage exchange with implant of a mega-prosthesis. J Chemother. 2017;29(6):386–8.

Nowbakht C, Garrity K, Webber N, Eraso J, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Prosthetic joint infection due to histoplasma capsulatum complicating a total knee arthroplasty. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx118.

Cooper LG, Heydemann J, Misenhimer G, Antony S. Use of intra-articular amphotericin b in the treatment of Candida parasilosis and albicans in prosthetic joint infections (PJI): a novel approach to this difficult problem. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2017;17(1):36–42.

Cobo F, Rodríguez-Granger J, López EM, Jiménez G, Sampedro A, Aliaga-Martínez L, Navarro-Marí JM. Candida-induced prosthetic joint infection. A literature review including 72 cases and a case report. Infect Dis (Lond). 2017;49(2):81–94.

Domínguez DC, Camacho E, Antony S. The role of molecular technology and prolonged cultures in the diagnosis of fungal prosthetic joint infections and orthopedic-related devices. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2016;24(5):e35–6.

Geng L, Xu M, Yu L, Li J, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Chen J. Risk factors and the clinical and surgical features of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a retrospective analysis of eight cases. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(2):991–9.

Jenny JY, Goukodadja O, Boeri C, Gaudias J. May one-stage exchange for Candida albicans peri-prosthetic infection be successful? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102(1):127–9.

Arbeloa-Gutierrez L, Kuberski T, Johnson SM, Sagastibelza I, Alaez JI, Pappagianis D. Reactivation of coccidioidomycosis: a prosthetic joint infection in Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(2):183–6.

Wang QJ, Shen H, Zhang XL, Jiang Y, Wang Q, Chen YS, Shao JJ. Staged reimplantation for the treatment of fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection following primary total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(2):151–6.

Shah NB, Shoham S, Nayak S. Cryptococcus neoformans prosthetic joint infection: case report and review of the literature. Mycopathologia. 2015;179(3):275–8.

Zhu Y, Yue C, Huang Z, Pei F. Candida glabrata infection following total hip arthroplasty: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7(2):352–4.

Klatte TO, Kendoff D, Kamath AF, Jonen V, Rueger JM, Frommelt L, Gebauer M, Gehrke T. Single-stage revision for fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection: a single-centre experience. Bone Jt J. 2014;96-B(4):492–6.

Presman B, Christensen JJ, Broeng L, Marckmann P, Nielsen XC. Deep infection with Candida albicans following total hip replacement: two case reports. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22(4):e72–3.

Lidder S, Tasleem A, Masterson S, Carrington R. Candida tropicalis: diagnostic dilemmas for an unusual prosthetic hip infection. J R Army Med Corps. 2013;159:123–5.

Villamil-Cajoto I, Eynde-Collado A, Otero L, Vicedo MV. Personal autonomy in the management of candidal prosthetic joint infection. Open Med. 2012;7(4):539–41.

MacGregor RR, Schimmer BM, Steinberg ME. Results of combined amphotericin B-5-fluorcytosine therapy for prosthetic knee joint infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(4):451–5.

Lichtman EA. Candida infection of a prosthetic shoulder joint. Skelet Radiol. 1983;10(3):176–7.

Younkin S, Evarts CM, Steigbigel RT. Candida parapsilosis infection of a total hip-joint replacement: successful reimplantation after treatment with amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine. A case report. JBJS. 1984;66(1):142–3.

Lim EV, Stern PJ. Candida infection after implant arthroplasty. A case report. JBJS. 1986;68(1):143–5.

Rabin OD, Richard JH, Daniel MM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89–96.

Chiu W-K, Chung K-Y, Cheung K-W, Chiu K-H. Candida parapsilosis total hip arthroplasty infection: case report and literature review. J Orthop Trauma Rehabil. 2013;17(1):33–6.

Deelstra JJ, Neut D, Jutte PC. Successful treatment of Candida albicans-infected total hip prosthesis with staged procedure using an antifungal-loaded cement spacer. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(2):374.e375-374.e378.

Austen S, van der Weegen W, Verduin CM, van der Valk M, Hoekstra HJ. Coccidioidomycosis infection of a total knee arthroplasty in a nonendemic region. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(2):375.e313-375.e315.

Hall RL, Frost RM, Vasukutty NL, Minhas H. Candida glabrata: an unusual fungal infection following a total hip replacement. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006491.

Anagnostakos K, Kelm J, Schmitt E, Jung J. Fungal periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections: clinical experience with a 2-stage treatment protocol. J Arthroplast. 2012;27(2):293–8.

Springer J, Chatterjee S. Candida albicans prosthetic shoulder joint infection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on multidrug therapy. JCR J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18(1):52–3.

Lackner M, De Man FH, Eygendaal D, Wintermans RGF, Kluytmans JA, Klaassen CH, Meis JF. Severe prosthetic joint infection in an immunocompetent male patient due to a therapy refractory Pseudallescheria apiosperma. Mycoses. 2011;54(s3):22–7.

Gottesman-Yekutieli T, Dan M, Shwartz O, Edelman A, Hendel D. Pseudallescheria boydii infection of a prosthetic hip joint—an uncommon infection in a rare location. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342(3):250–3.

Wu M-H, Hsu K-Y. Candidal arthritis in revision knee arthroplasty successfully treated with sequential parenteral-oral fluconazole and amphotericin B-loaded cement spacer. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(2):273–6.

Graw B, Woolson S, Huddleston JI. Candida infection in total knee arthroplasty with successful reimplantation. J Knee Surg. 2010;23(3):169–74.

Johannsson B, Callaghan JJ. Prosthetic hip infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans: case report. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64(1):76–9.

Bland CM, Thomas S. Micafungin plus fluconazole in an infected knee with retained hardware due to Candida albicans. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(3):528–31.

Fabry K, Verheyden F, Nelen G. Infection of a total knee prosthesis by Candida glabrata: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(1):119–21.

Lerch K, Kalteis T, Schubert T, Lehn N, Grifka J. Prosthetic joint infections with osteomyelitis due to Candida albicans. Mycoses. 2003;46(11–12):462–6.

Açikgöz ZC, Sayli U, Avci S, Doğruel H, Gamberzade S. An extremely uncommon infection: Candida glabrata arthritis after total knee arthroplasty. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(5):394–6.

David MP, Douglas RO, Michael RK, Arlen DH. Delayed reimplantation arthroplasty for candidal prosthetic joint infection: a report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(7):930–8.

Cutrona AF, Shah M, Himes MS, Miladore MA. Rhodotorula minuta: an unusual fungal infection in hip-joint prosthesis. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2002;31(3):137–40.

Merrer J, Dupont B, Nieszkowska A, De Jonghe B, Outin H. Candida albicans prosthetic arthritis treated with fluconazole alone. J Infect. 2001;42(3):208–9.

Yang S-H, Pao J-L, Hang Y-S. Staged reimplantation of total knee arthroplasty after Candida infection. J Arthroplast. 2001;16(4):529–32.

Wada M, Baba H, Imura S. Prosthetic knee Candida parapsilosis infection. J Arthroplast. 1998;13(4):479–82.

Fowler VG Jr, Nacinovich FM, Alspaugh JA, Corey GR. Prosthetic joint infection due to Histoplasma capsulatum: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(4):1017.

Nayeri F, Cameron R, Chryssanthou E, Johansson L, Söderström C. Candida glabrata prosthesis infection following pyelonephritis and septicaemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29(6):635–8.

Cardinal E, Braunstein EM, Capello WN, Heck DA. Candida albicans infection of prosthetic joints. Orthopedics. 1996;19(3):247–51.

Hirsch BE, Farber BF, Shapiro JF, Kennelly S. Successful treatment of Aureobasidium pullulans prosthetic hip infection. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1996;5(3):205–6.

Evans RP, Nelson CL. Staged reimplantation of a total hip prosthesis after infection with Candida albicans. A report of two cases. JBJS. 1990;72(10):1551–3.

Dutronc H, Dauchy FA, Cazanave C, Rougie C, Lafarie-Castet S, Couprie B, Fabre T, Dupon M. Candida prosthetic infections: case series and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(11–12):890–5.

Goodman JS, Seibert DG, Reahl GE Jr, Geckler RW. Fungal infection of prosthetic joints: a report of two cases. J Rheumatol. 1983;10(3):494–5.

Koch AE. Candida albicans infection of a prosthetic knee replacement: a report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(2):362–5.

Iskander MK, Khan MA. Candida albicans infection of a prosthetic knee replacement. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(10):1594–5.

Levine M, Rehm SJ, Wilde AH. Infection with Candida albicans of a total knee arthroplasty: case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;226:235–9.

Mark L, David T, Matthew Bidwell G. Fungal prosthetic arthritis: presentation of two cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(5):1038–43.

Paul J, White SH, Nicholls KM, Crook DW. Prosthetic joint infection due to Candida parapsilosis in the UK: case report and literature review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11(9):847–9.

Austin KS, Testa NN, Luntz RK, Greene JB, Smiles S. Aspergillus infection of total knee arthroplasty presenting as a popliteal cyst: Case report and review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7(3):311–4.

Tunkel AR, Thomas CY, Wispelwey B. Candida prosthetic arthritis: report of a case treated with fluconazole and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1993;94(1):100–3.

White A, Goetz MB. Candida parapsilosis prosthetic joint infection unresponsive to treatment with fluconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(4):1068–9.

Hennessy MJ. Infection of a total knee arthroplasty by Candida parapsilosis. A case report of successful treatment by joint reimplantation with a literature review. Am J Knee Surg. 1996;9(3):133–6.

Cushing RD, Fulgenzi WR. Synovial fluid levels of fluconazole in a patient with Candida parapsilosis prosthetic joint infection who had an excellent clinical response. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(8):950.

Fukasawa N, Shirakura K. Candida arthritis after total knee arthroplasty—a case of successful treatment without prosthesis removal. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68(3):306–7.

Simonian PT, Brause BD, Wickiewicz TL. Candida infection after total knee arthroplasty. Management without resection or amphotericin B. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(7):825–9.

Selmon GPF, Slater RNS, Shepperd JAN, Wright EP. Successful 1-stage exchange total knee arthroplasty for fungal infection. J Arthroplast. 1998;13(1):114–5.

Brooks DH, Pupparo F. Successful salvage of a primary total knee arthroplasty infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Arthroplast. 1998;13(6):707–12.

Baumann PA, Cunningham B, Patel NS, Finn HA. Aspergillus fumigatus infection in a mega prosthetic total knee arthroplasty: salvage by staged reimplantation with 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplast. 2001;16(4):498–503.

Ramamohan N, Zeineh N, Grigoris P, Butcher I. Candida glabrata infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Infect. 2001;42(1):74–6.

Marra F, Robbins GM, Masri BA, Duncan C, Wasan KM, Kwong EH, Jewesson PJ. Amphotericin B-loaded bone cement to treat osteomyelitis caused by Candida albicans. Can J Surg. 2001;44(5):383–6.

Wyman J, McGough R, Limbird R. Fungal infection of a total knee prosthesis: successful treatment using articulating cement spacers and staged reimplantation. Orthopedics. 2002;25(12):1391–4 (discussion 1394).

Langer P, Kassim RA, Macari GS, Saleh KJ. Aspergillus infection after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2003;32(8):402–4.

Lazzarini L, Manfrin V, de Lalla F. Candidal prosthetic hip infection in a patient with previous candidal septic arthritis. J Arthroplast. 2004;19(2):248–52.

Gaston G, Ogden J. Candida glabrata periprosthetic infection: a case report and literature review. J Arthroplast. 2004;19(7):927–30.

Baecker H, Frieler S, Geßmann J, Pauly S, Schildhauer TA, Hanusrichter Y. Three-stage revision arthroplasty for the treatment of fungal periprosthetic joint infection: outcome analysis of a novel treatment algorithm. Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(8):671–8.

Ueng SWN, Lee C-Y, Hu C-C, Hsieh P-H, Chang Y. What is the success of treatment of hip and knee candidal periprosthetic joint infection? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):3002–9.

Ji B, Zhang X, Xu B, Guo W, Mu W, Cao L. Single-stage revision for chronic fungal periprosthetic joint infection: an average of 5 years of follow-up. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(8):2523–30.

Kim J-K, Lee D-Y, Kang D-W, Ro D-H, Lee MC, Han H-S. Efficacy of antifungal-impregnated cement spacer against chronic fungal periprosthetic joint infections after total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2018;25(4):631–7.

Brown TS, Petis SM, Osmon DR, Mabry TM, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP. Periprosthetic joint infection with fungal pathogens. J Arthroplast. 2018;33(8):2605–12.

Bruce AS, Kerry RM, Norman P, Stockley I. Fluconazole-impregnated beads in the management of fungal infection of prosthetic joints. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2001;83(2):183–4.

Bartalesi F, Fallani S, Salomoni E, Marcucci M, Meli M, Pecile P, Cassetta MI, Latella L, Bartoloni A, Novelli A. Candida glabrata prosthetic hip infection. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2012;41(11):500–5.

Dumaine V, Eyrolle L, Baixench MT, Paugam A, Larousserie F, Padoin C, Tod M, Salmon D. Successful treatment of prosthetic knee Candida glabrata infection with caspofungin combined with flucytosine. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(4):398–9.

Lejko-Zupanc T, Mozina E, Vrevc F. Caspofungin as treatment for Candida glabrata hip infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;25(3):273–4.

Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89–96.

Antony S, Domínguez DC, Jackson J, Misenheimer G. Evaluation and treatment of Candida species in prosthetic joint infections: two case reports and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2008;16(6):354–9.

Reddy KJ, Shah JD, Kale RV, Reddy TJ. Fungal prosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty. Indian J Orthop. 2013;47(5):526–9.

Azam A, Singh P, Singh V, Siddiqui A. A rare case of Candida tropicalis infection of a total hip arthroplasty: a case report and review of literature. Malays Orthop Jo. 2008;2(2):43–6.

Kuo F-C, Goswami K, Shohat N, Blevins K, Rondon AJ, Parvizi J. Two-stage exchange arthroplasty is a favorable treatment option upon diagnosis of a fungal periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplast. 2018;33(11):3555–60.

Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(16):1645–54.

Cordero-Ampuero J. Girdlestone procedure: when and why. HIP Int. 2012;22(8_suppl):36–9.

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez JA, Walsh TJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of Candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;62(4):e1–50.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Margaret Hoogland, MLS from the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences Library for assistance in the literature review search.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Joan Duggan; methodology, Joan Duggan and Caitlyn Hollingshead; formal analysis, Caitlyn Hollingshead and Victoria Starnes; investigation, Victoria Starnes and Caitlyn Hollingshead; data curation, Caitlyn Hollingshead and Victoria Starnes; writing—original draft preparation, Victoria Starnes and Caitlyn Hollingshead; writing—review and editing, Joan Duggan; supervision, Joan Duggan and Caitlyn Hollingshead. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Victoria Starnes, Joan Duggan, and Caitlyn Hollingshead declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Toledo and ProMedica Health Systems. Patient consent was waived as this was a retrospective review and it was not feasible to contact all patients.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentation: Portions of this manuscript were previously presented at IDWeek 2023 in Boston, MA October 11–15, 2023. Portions of this manuscript were previously presented at the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences Research Symposium 2023 in Toledo, OH, September 28, 2023.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Starnes, V., Duggan, J. & Hollingshead, C. Fungal Prosthetic Joint Infection: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Infect Dis Ther 13, 1051–1065 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-00964-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-00964-9