Abstract

Introduction

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is a serious and fatal fungal infection that affects individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Despite treatment, recurrence of symptoms is common and could lead to poor outcomes. Corticosteroids are not always useful in treating symptom recurrence following HIV/CM; thus, alternative therapy is needed. Thalidomide has been reported to be effective in treating symptom recurrence in several patients with HIV/CM. This retrospective study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of thalidomide in the treatment of symptom recurrence following HIV/CM.

Methods

Patients who were treated with thalidomide for symptom recurrence following HIV/CM were retrospectively included. Clinical outcomes and adverse events were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Sixteen patients admitted between July 2018 and September 2020 were included in the analysis. During a median follow-up period of 295 (166, 419) days, all patients achieved clinical improvement in a median of 7 (4, 20) days. Among them, nine (56%) achieved complete resolution of symptoms at a median of 187 (131, 253) days, including 40% (2/5) of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), 50% (3/6) of patients with elevated ICP only, and 80% (4/5) of patients with symptoms only. Seven (43%) patients experienced nine episodes of adverse events, but no severe adverse event attributable to thalidomide was observed. None of the patients withdrew from thalidomide due to adverse events.

Conclusion

Thalidomide appears to be effective and safe in treating different types of symptom recurrence in HIV/CM. This study provides preliminary evidence supporting future randomized clinical trials to further investigate the efficacy and safety of thalidomide in treating symptom recurrence in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out the study? | |

Recurrence of symptoms is prevalent and sometimes fatal in HIV-infected individuals with cryptococcal meningitis. | |

Treatment option is limited for symptom recurrence without fungal relapse. | |

What was learned from the study? | |

Thalidomide treatment led to clinical and radiological resolution, and showed safety in this pilot study. | |

Randomized clinical trials are needed to further declare the efficacy and safety of thalidomide therapy. |

Introduction

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is a meningoencephalitis caused by the encapsulated yeasts, Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. CM primarily affects individuals with immune deficiency, such as those with HIV infection, innate immunological defects, and hematological malignancies and those undergoing immunosuppressive treatment. Patients usually present with a progressive headache, vomiting, vision loss, or even coma. In 2020, the global incidence of HIV-associated CM was approximately 152,000, leading to 112,000 cryptococcal-related deaths [1]. The first-line antifungal treatment for CM in people living with HIV (HIV/CM) consists of induction therapy with amphotericin B and flucytosine, followed by consolidation therapy with fluconazole and flucytosine, and maintenance therapy with fluconazole [2]. Antiretroviral therapy is recommended to start 4–6 weeks after initiation of antifungal treatment [2]. Recurrence of symptoms is common in HIV/CM after relief of primary cryptococcal meningitis, including paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), persistent elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) only, persistent symptoms only, and fungal relapse [3]. Headache, vomiting, and seizures are most commonly seen in patients with recurrence of symptoms [3]. Mortality is high in patients with HIV/CM who develop IRIS or fungal relapse [2,3,4]. While antifungal therapy is recommended for patients with fungal relapse, there is a lack of optimal therapy for other types of symptom recurrence in HIV/CM. Standard therapy for IRIS in patients with HIV/CM involves corticosteroids, but poor response, dependency, and adverse events are common [4].

Thalidomide is currently used to treat multiple myeloma in combination with dexamethasone, and is also used to treat autoimmune diseases, such as severe skin lesions caused by leprosy. Recently, it was investigated for symptom relief of immune reconstitution syndrome in tuberculous meningitis [5]. Thalidomide was reported to alleviate paradoxical IRIS in three cases of HIV/CM, potential through antagonistic effect against TNF-α [6, 7]. However, it is prohibited in pregnant women due to the increased risk of life-threatening birth defects or stillbirth.

Currently, evidence is limited for the use of thalidomide in IRIS of HIV/CM, and even less is known about its efficacy and safety in the treatment of persistent elevated ICP and persistent symptoms. In this study, we aimed to retrospectively analyze the efficacy and safety of thalidomide treatment in patients with HIV/CM with symptom recurrence other than fungal relapse.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, we examined patients who experienced recurrence of symptoms following HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis (HIV/CM) and were admitted to the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center between July 2018 and September 2020. This center is a national clinical training center of HIV/AIDS and the designated clinical center for treating HIV/AIDS in Shanghai. Over 2000 inpatients with HIV/AIDS receive care at this center annually.

Electronic medical record system and laboratory information system data were retrospectively collected for analysis. The Ethics Committee of Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center granted ethical approval for this study (2021-S051-01). Written informed consent was waived since the study utilized only retrospective data. The privacy of participants was held in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

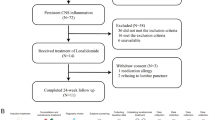

Our analysis included patients with HIV/CM who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) HIV diagnosis was made by a positive western blot HIV antibody test and/or a serum HIV viral load of no less than 5000 copies/mL; (2) CM diagnosis was based on Indian ink staining or culture with the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); (3) HIV and CM were treated according to the guideline [5]; (4) patients experienced new or worsening symptoms after antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation; and (5) culture for Cryptococcus neoformans was negative with the CSF at the time of recurrence. Patients were excluded if they met the following criteria: (1) thalidomide usage since the inductive period of CM; (2) patients who never visited after thalidomide treatment; (3) other etiologies of central nervous system infection; or (4) patients who were already recovering with corticosteroids taper therapy. Participants were categorized into IRIS, persistent elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) only, and persistent symptoms only. IRIS referred to culture-negative symptom recurrence after clinical and immunological response to HAART, as described in the literature [8]. Persistent elevated ICP was defined if the participant had culture-negative symptom recurrence and an open ICP of over 200 mmH2O, despite of IRIS. Persistent symptoms only refer to culture-negative symptom recurrence without IRIS or elevated ICP [2].

In our clinical practice, patients were requested to undergo magnetic resonance (MR) scans and lumbar punctures before and within 1 month after initiation of thalidomide treatment. Antifungal and antiretroviral therapies were maintained in accordance with the guideline [4]. Patients were followed up in outpatient or inpatient services as per their demand. Thalidomide tablets were prescribed in 25 mg pieces by Changzhou Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Changzhou, China). The tablets were prescribed orally at 50, 75, or 100 mg per day initially, determined by clinical decision. For patients already on corticosteroid treatment, corticosteroids were gradually tapered when clinically improved after thalidomide usage. Thalidomide was gradually withdrawn if the patient’s clinical status was stable. Patients were followed up until thalidomide withdrawal or mortality. DAIDS Adverse Event Grading Tables, Corrected v 2.1, was used to grade and define adverse effects.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 22 (IBM, NY, USA). Depending on distribution, continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as median and range. Pearson chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were utilized to compare the difference in rate of symptoms at primary presentation and symptom recurrence. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests were used to assess the differences in the CSF levels of ICP, white blood cell, protein, and glucose before and after thalidomide treatment. Graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, US).

Results

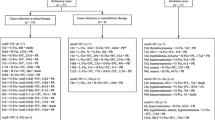

A total of 25 patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. Of these, nine patients were excluded for various reasons including commencement of thalidomide therapy during the inductive phase of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in two patients, positive response to dexamethasone taper therapy in two patients, non-attendance at follow-up visits after thalidomide treatment in three patients, and diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) mycobacterial infection in two patients. Of the 16 patients who were enrolled in the study, 75% were male with a median age of 43 (range, 32–56) years. All patients were of Chinese ethnicity, and the only etiology observed was Cryptococcus neoformans. Recurrence of symptoms was classified into three categories: paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in 31% of patients, persistent elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) in 38% of patients, and persistent symptoms only in 31% of patients. Symptom recurrence occurred at a median time of 171 (range 19–361) days after initiation of cART treatment. Thalidomide therapy was initiated at a median time of 13 (range 6–29) days following symptom recurrence. Sixty-nine percent of patients had preexisting corticosteroid usage that was not tapered. The median CD4 count was 28 (range 11–53) cells/μL at nadir and 72 (range 48–86) cells/μL prior to initiation of thalidomide therapy. Four (25%) patients had 6 episodes of underlying comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, horseshoe kidney, cytomegalovirus retinitis, myocardial bridge, hepatitis B, and lung cancer. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt (V–P shunt) had been performed in 13% of the patient population (Table 1). Patients were more likely to report vision changes (P = 0.03) and less likely to report nausea or vomiting (P = 0.006) at symptom recurrence compared with the primary presentation (Table 2).

All patients survived during a median follow-up time of 295 (range 166–419) days. Among the 13 patients who underwent lumbar puncture within 1 month after initiation of thalidomide therapy, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) characteristics were compared with those obtained prior to thalidomide treatment. There were no significant changes in median ICP, total protein, white blood cell count (WBC), or CSF glucose levels (Table 3). However, normal ICP was observed in 17% (1/6) of patients with elevated ICP only (Fig. 1).

During the follow-up period, all patients experienced clinical improvement with a median time to improvement of 7 (range 4–20) days. Nine patients (56%) achieved complete resolution of symptoms with a median time to resolution of 187 (range 131–253) days, including 40% (2/5) of patients with IRIS, 50% (3/6) of patients with elevated ICP only, and 80% (4/5) of patients with symptoms only. Of the 13 patients who underwent repeat magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after thalidomide therapy, 85% achieved radiological improvement with a median time to improvement of 36 (range 10–121) days after treatment (Table 4). One patient (8%) achieved complete radiological resolution at day 178. A pair of typical image before and after thalidomide treatment is shown in Fig. 2. Fifteen patients (94%) were able to reduce the dosage of thalidomide at a median time of 45 (range 28–87) days. Six patients (38%) were able to withdraw from thalidomide therapy at a median time of 70 (range 46–195) days after treatment (Table 4).

Seven patients (44%) experienced a total of nine episodes of adverse events (AEs). Three patients (19%) experienced AEs that were attributable to thalidomide therapy, including rash in one patient and elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in two patients. Other AEs included chest pain, hypertension, hypokalemia, anemia, and cerebral infarction. No severe adverse events (SAEs) were attributable to thalidomide therapy, and no patients withdrew from thalidomide therapy due to AEs (Table 5). There were no significant differences in the incidence of AEs among patients initiated on a dose of 50 mg, 75 mg, or 100 mg of thalidomide daily (Table 6).

Discussion

China has a reported HIV prevalence of approximately 0.8% as of the end of 2021. Antiretroviral treatment is provided by primary physicians in rural areas and specialists in urban, including free regimen provided by the government and more choices covered by medical insurances. Still, a study between 2010 and 2020 showed that 43.26% of patients presented late for follow-up care, and the author believed that stigma is a major barrier to timely diagnosis [9]. Among them, CM remains a major threat to life, and there is a lack of consensus on managing symptomatic relapse following HIV/CM. This pilot study examines a potential therapeutic option for these patients.

The study found that symptoms recurred 171 (19,361) days after ART treatment, similar to previous literature reports suggesting long-lasting symptom recurrence. The study excluded patients with positive fungal cultures at recurrence, possibly requiring intensified antifungal therapy rather than immune modulation. Patients had less clinical presentation of increased intracranial pressure and had more focal symptoms at recurrence compared with their primary manifestation. Theoretically, focal symptoms are more likely to be related with inflammation and angiogenesis, leaving space for anti-inflammatory therapy [10]. The antagonism of thalidomide against TNF-α might explain its efficacy in relieving symptom recurrence following HIV/CM [11].

In this study, all the participants achieved clinical improvement after treatment with thalidomide, with a dosage of 50 mg, 75 mg, or 100 mg per day. More than half achieved complete resolution of symptoms in the study period. Clinical and radiological efficacy was observed in patients with IRIS, elevated intracranial pressure, and symptoms alone. These data add evidence to previous studies about using thalidomide in IRIS following of HIV/CM, as they constitute the largest sample size as far as we know [6, 7]. It also suggested thalidomide as a novel solution for cases with elevated intracranial pressure and symptoms alone. For the reason above, the study supports the efficacy of thalidomide treatment in treating symptom recurrence with HIV/CM and informs future clinical trial design.

Adverse events (AE) were observed in 44% of 16 participants, but only a minor fraction was attributable to thalidomide treatment. There were no reports of serious adverse events (SAEs) or treatment discontinuation attributable to thalidomide treatment. Peripheral neuropathy was not noted in this study, possibly due to the small sample size and lower dosage of thalidomide compared with the literature [5]. No matter how, compared with metabolic, osteoarticular, infectious, adrenal, gastrointestinal, ophthalmological, and neuropsychiatric manifestations with prolonged corticosteroid use, the adverse events described in this study seem to be minimal and acceptable [12]. The study favors thalidomide in treating symptom recurrence following HIV/CM from the perspective of safety.

The retrospective and unblinded designing may lead to biased measurement of potential therapeutic and adverse events, and the study’s small sample size restricts its statistical power. Also, the time of follow-up might not be enough since 62% of the participants were still on treatment with thalidomide. Data may be missed if patients went to other hospitals. These call for future prospective studies to further explore thalidomide’s efficacy and safety for symptom recurrence following HIV/CM.

Conclusion

This pilot study provides preliminary evidence to support the efficacy and safety of thalidomide treatment in patients experiencing different types of symptom recurrence following HIV/CM. These findings provide a basis for designing future randomized clinical trials to evaluate thalidomide’s treatment outcomes.

References

Rajasingham R, Govender NP, Jordan A, Loyse A, Shroufi A, Denning DW, et al. The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: a modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(12):1748–55.

Guidelines for diagnosing, preventing and managing cryptococcal disease among adults, adolescents and children living with HIV [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; [cited 2023Feb18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052178

Bahr NC, Skipper CP, Huppler-Hullsiek K, Ssebambulidde K, Morawski BM, Engen NW, Nuwagira E, Quinn CM, Ramachandran PS, Evans EE, Lofgren SM, Abassi M, Muzoora C, Wilson MR, Meya DB, Rhein J, Boulware DR. Recurrence of symptoms following cryptococcal meningitis: characterizing a diagnostic conundrum with multiple etiologies. Clin Infect Dis. 2022:ciac853. Online ahead of print.

Guidelines for The Diagnosis. Prevention and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents and children: supplement to the 2016 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Panda PK, Panda P, Dawman L, Sihag RK, Sharawat IK. Efficacy and safety of thalidomide in patients with complicated central nervous system tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(4):1024–30.

Brunel AS, Reynes J, Tuaillon E, Rubbo PA, Lortholary O, Montes B, Le Moing V, Makinson A. Thalidomide for steroid-dependent immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromes during AIDS. AIDS. 2012;26(16):2110–2.

Kwon HY, Han YJ, Im JH, Baek JH, Lee JS. Two cases of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV patients treated with thalidomide. Int J STD AIDS. 2019;30(11):1131–5.

Haddow LJ, Colebunders R, Meintjes G, Lawn SD, Elliott JH, Manabe YC, Bohjanen PR, Sungkanuparph S, Easterbrook PJ, French MA, Boulware DR; International Network for the Study of HIV-associated IRIS (INSHI). Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(11): 791–802

Sun C, Li J, Liu X, Zhang Z, Qiu T, Hu H, Wang Y, Fu G. HIV/AIDS late presentation and its associated factors in China from 2010 to 2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):96.

. Balasko A, Keynan Y. Shedding light on IRIS: from pathophysiology to treatment of cryptococcal meningitis and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-infected individualsHIV Med. 2019;20 (1):1–10.

Franks ME, Macpherson GR, Figg WD. Thalidomide. Lancet. 2004;363(9423):1802–11.18

Buchman ALMD. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:289–94.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The study was supported by Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (20MC1920100), Shanghai "Rising stars of Medical Talent" Youth Development Program, Specialist Program (No. 2019–72) and Shanghai Talent Development Fund (2020089). The rapid service fee was covered by the Shanghai major projects on infectious diseases (GWV-10.1-XK02).

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Jun Chen; Methodology: Jun Chen, Renfang Zhang, Li Liu; Formal analysis and investigation: Tangkai Qi, Fang Chen; Writing—original draft preparation: Tangkai Qi, Siyue Ma; Writing—review and editing: Tangkai Qi, Jun Chen; Funding acquisition: Jun Chen, Yinzhong Shen; Resources: Zhenyan Wang, Yang Tang, Wei Song, Jianjun Sun, Junyang Yang, Shuibao Xu, Bihe Zhao; Supervision: Jun Chen, Renfang Zhang, Li Liu, Yinzhong Shen.

Disclosure

Tangkai Qi, Fang Chen, Siyue Ma, Renfang Zhang, Li Liu, Zhenyan Wang, Yang Tang, Wei Song, Jianjun Sun, Junyang Yang, Shuibao Xu, Bihe Zhao, Yinzhong Shen and Jun Chen have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The Ethics Committee of Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center granted ethical approval for this study (2021-S051-01). Written informed consent was waived since the study utilized only retrospective data. The privacy of participants was held in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, T., Chen, F., Ma, S. et al. Thalidomide for Recurrence of Symptoms following HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. Infect Dis Ther 12, 1667–1675 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-023-00817-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-023-00817-x