Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the etiology of common respiratory pathogens in children < 2 years of age hospitalized with pneumonia in Xiamen from 2014 to 2017.

Methods

The medical records of 5581 children with pneumonia were retrospectively reviewed. Direct immunofluorescent test was used for respiratory virus testing. Bacteria were detected by conventional culture method. The results of pathogen detection at admission were analyzed as well as the clinical outcomes of children.

Results

The burden of hospitalized children with pneumonia was highest among infants < 6 months old (58.2%). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was the most common respiratory virus (26.0%) followed by parainfluenza (4.8%) and adenovirus (3.2%). Haemophilus influenzae was the most common bacteria detected (16.6%) followed by Moraxella catarrhalis (13.4%), Staphylococcus aureus (13.0%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (12.3%), Escherichia coli (5.1%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (4.8%). Notably, RSV and K. pneumoniae were detected more frequently in severe pneumonia (35.0% and 10.9%) versus mild pneumonia (25.6% and 4.6%), with higher rates of ICU admissions, longer hospital stays and higher hospital costs compared to those infected with other respiratory pathogens.

Conclusions

Among children < 2 years of age hospitalized with pneumonia in Xiamen, RSV was the most common respiratory virus, while H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae remained the predominant bacterial pathogens detected. Considering the low implementation rate of vaccines against pneumococcal and Hib pneumonia in China, there is an urgent need to increase both vaccination rates to reduce pneumococcal and Hib disease burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Recent epidemiological studies of pneumonia pathogens have rarely been reported in China. |

The pathogen spectrum of pneumonia in children may change greatly because of the introduction of vaccines against bacterial pneumonia and influenza in China in recent years. |

What was learned from the study? |

The burden of hospitalization of children with pneumonia was highest among infants < 6 months old in Xiamen. |

Among children < 2 years of age hospitalized with pneumonia in Xiamen, RSV was the most common respiratory virus, while H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae remained the predominant bacterial pathogens detected. |

Considering the low implementation rate of vaccines against pneumococcal and Hib pneumonia in China, there is an urgent need to increase both vaccination rates to reduce pneumococcal and Hib disease burden. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14673816.

Introduction

Pneumonia is the disease with the highest morbidity and mortality among children < 5 years of age worldwide [1]. Pneumonia among children contributes to a high disease burden in China. A systematic review estimated the annual incidence of clinical pneumonia in China to be 84 episodes per 1000 children under 5 years of age (95% confidence interval: 40.0–166.0), accounting for approximately 5% of all clinical pneumonia and severe pneumonia cases worldwide in 2015 [2]. The annual incidence of community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization was highest among children < 2 years of age [3].

Knowledge of the pathogens that cause pneumonia and severe pneumonia is needed to improve clinical management and promote the rational use of antibiotics [4]. Respiratory virus infections, such as RSV, influenza virus (flu), adenovirus (ADV) and parainfluenza viruses (PIVs), are the most common causes of pneumonia [5]. In addition, one-fourth to one-third of pneumonia cases are attributed to partially gram-positive (S. pneumoniae and S. aureus) and gram-negative bacteria (H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, E. coli, K. pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [6,7,8].

The majority of epidemiological studies of pneumonia pathogens were conducted in China before 2015 [9,10,11,12]. However, the etiology of pneumonia in children may have changed significantly because of the introduction of vaccines against bacterial pneumonia (H. influenzae type b [Hib] and S. pneumoniae) and influenza in China in recent years. This retrospective study investigated common respiratory pathogens in children < 2 years of age hospitalized for pneumonia in Xiamen from 2014 to 2017, providing basic data on the etiological changes of pneumonia in China.

Methods

Study Population

From 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2017, the medical records of children hospitalized for pneumonia at Xiamen Maternal and Child Health Hospital were retrospectively reviewed. Subjects meeting the following criteria were included: (1) age ≤ 2 years old; (2) discharge diagnosis included pneumonia. Children were excluded if their first three discharge diagnoses did not include pneumonia. The diagnosis criteria for pneumonia in children in this study were as follows: (1) radiographic evidence of pulmonary infiltrates; (2) at least three of the following symptoms: fever (body temperature ≥ 38.0 °C), shortness of breath (≥ 60 breaths/min for infants < 2 months old, ≥ 50 breaths/min for breaths/min for children 2–12 months of age and ≥ 40 breaths per min for children 12–24 months old), cough, auscultation findings (rhonchi, crackles or bronchial breath sounds) or chest tightness. Severe childhood pneumonia was defined if the child with pneumonia had severe ventilation dysfunction, intrapulmonary (e.g., acute respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, pyothorax, pulmonary abscess, etc.) or extrapulmonary (e.g., anemia, septic shock, viral encephalitis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, etc.) complications.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Maternal and Child Health Hospital and the School of Public Health of Xiamen University and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Medical records were de-identified of all personally identifiable information.

Data Collection

The following information was collected from medical records: (1) basic information: age, sex and date of admission; (2) results of pathogen testing at admission: RSV, influenza virus A and B (Flu A and Flu B), parainfluenza virus type 1, 2 and 3 (PIV I, II and III) and adenovirus (ADV) were tested by direct immunofluorescent test (Diagnostic Hybrids, Inc., USA) with nasal swabs; sputum, blood, pleural fluid, and/or bronchoalveolar lavage specimens were tested for typical bacteria (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, K. pneumoniae and E. coli, etc.) using conventional culture method; (3) outcome: ICU admission, length of hospital stay and hospitalization cost.

Statistical Analysis

For categorical variable comparation, χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used. All tests were two-tailed, and P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Graphs were generated by GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Study Characteristics

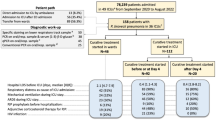

From October 1, 2014, to September 30, 2017, a total of 5581 children < 2 years of age hospitalized with pneumonia were included in this study. Of these, 220 (3.9%) cases were classified as severe pneumonia. The median age was 4.4 months (IQR 1.4–10.5). The main population of pneumonia was infants < 6 months of age (58.2%). In addition, the rate of severe pneumonia was higher among them than among children aged 6–24 months (5.0% vs. 2.5%, P < 0.001). The male-to-female ratio was 1.87. More pneumonia (30.2%) occurred in Spring (March to May) (Table 1). The rate of severe pneumonia cases (5.3%) was highest from October 2016 to September 2017.

Etiologic Agent Distribution

Of the 5581 children with pneumonia, viral or bacterial pathogens were detected in 3768 (67.5%), viral pathogen only in 1810 (32.4%), one viral pathogen only in 810 (14.5%), viral-viral co-detection in 70 (1.3%), bacterial-viral co-detection in 930 (16.7%) and bacterial pathogen only in 1958 (35.1%) (Table 2). RSV was the most common respiratory virus (26.0% of cases) followed by parainfluenza (4.8%) and adenovirus (3.2%). Bacteria were found in 51.7% of the children with pneumonia. H. influenzae (16.6%) had the highest detection rate followed by M. catarrhalis (13.4%), S. aureus (13.0%), S. pneumoniae (12.3%), E. coli (5.1%) and K. pneumoniae (4.8%). Notably, RSV and K. pneumoniae were detected more frequently in severe pneumonia (35.0% and 10.9%) versus mild pneumonia (25.6% and 4.6%) (Fig. 1).

RSV was more common in infants with pneumonia < 6 months of age than in older children (27.6% vs. 24.8%, P < 0.001), as were S. aureus (19.0% vs. 5.0%, P < 0.001), K. pneumoniae (7.2% vs. 1.6%, P < 0.001) and E. coli (7.5% vs. 1.8%, P < 0.001). Parainfluenza was more common in children with pneumonia > 6 months old than in infants with pneumonia (6.2% vs. 3.8%, P < 0.001), as were adenovirus (4.8% vs. 2.1%, P < 0.001), M. catarrhalis (16.4% vs. 11.2%, P < 0.001) and S. pneumoniae (20.1% vs. 6.6%, P < 0.001) (Table 3). Pneumonia peaked annually in the spring (March to May) (Fig. 2). Seasonal peaks of RSV occurred in late winter (February) and late summer (August). RSV circulated throughout the year, with positive rates ranging from 6.9 to 49.5%. There were no clear seasonal patterns for other viruses, with lower detection rates in each season (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, M. catarrhalis was detected frequently in winter, while H. influenzae showed a seasonal peak in spring (Fig. 2B).

Outcome of Children Hospitalized for Pneumonia

The rate of ICU admission was 9.4% (523/5581) among all children with pneumonia. The median length of hospital stay was 6 days (IQR 4–7), with median hospital charge of $629.2 (IQR 457.5–889.9). Infants with pneumonia < 6 months of age had a higher rate of ICU admission (12.4% vs. 5.2%, 5.2%), longer hospital stay (6 days vs. 5 days, 5 days) and higher hospital costs ($730.1 vs. $557.9, $507.2) compared to children with pneumonia aged 6–12 and 12–24 months. In terms of viral pathogens, the rate of ICU admissions for children with RSV infection (12.5%) was much higher than for children with ADV (9.8%), flu (6.8%) and PIV (3.6%) infections. The median length of hospital stays for children infected with RSV was 6 days, which was longer than for children infected with ADV (5 days), flu (4 days) and PIVs (5 days). In addition, the median hospitalization cost per child with RSV infection was $672.76, higher than for children with other virus infections. For bacterial pathogens, children with K. pneumoniae infection had the highest rate of ICU admission (15.3%) and the highest hospitalization costs (median $795.7, IQR 580.1–1101.6) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This retrospective study revealed that the burden of hospitalization for children with pneumonia was highest in infants < 6 months of age in Xiamen. Viruses were detected in 32.4% of children with pneumonia, and bacteria were detected in 51.7%. RSV was the most common respiratory virus (26.0%), and H. influenzae was the most commonly detected bacterium (16.6%).

RSV was detected more frequently in infants with pneumonia < 6 months of age than in older children with pneumonia (27.6% vs. 23.8%). In other studies, RSV was detected in approximately 17.3–24.6% of children with pneumonia < 5 years of age using PCR assays in China, with a higher detection rate in younger children with pneumonia [12,13,14], which was similar to our study. Parainfluenza, adenovirus and influenza were detected in 4.8%, 3.2% and 1% of children separately, slightly lower rates than in other regions of China [12, 14, 15]. In contrast to RSV, these three pathogens were more commonly found in older children with pneumonia. RSV infection occurred more frequently in early infancy [16]. Although infants < 6 months acquired maternal RSV-specific antibodies that provide protection, RSV-specific neutralizing antibodies decayed rapidly and provided protection only during the first 3 months of life [17, 18]. However, maternally derived influenza [19,20,21], ADV [22,23,24] and PIV [25] specific neutralizing antibodies can protect newborn infants < 6 months old from infection with these viruses. Therefore, most infections with influenza, ADV and PIVs [26] usually occurred in children between 7 and 36 months of age. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding can transfer maternal antibodies and protect infants against respiratory tract infections [27, 28]. Another strategy to increase maternal antibodies in infants is immunization during pregnancy, which is recommended in various countries for influenza, pertussis and tetanus vaccination programs [29,30,31]. In addition, group B Streptococcus and RSV vaccines for pregnant women are under development, which will contribute to the prevention of respiratory infectious diseases in children [32].

The proportion of bacterial detection was higher in our study (57.1%) than in other studies (15–46.2%) [3, 33,34,35]. The most frequently detected bacterial agents included H. influenzae (16.6%), M. catarrhalis (13.4%), S. aureus (13.0%), S. pneumoniae (12.3%), E. coli (5.1) and K. pneumoniae (4.8%), which were generally reported as the major microbes inducing bacterial pneumonia [6, 7, 12, 36]. It is worth noting that H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae remained the main bacterial agents after the introduction of a vaccine against bacterial pneumonia. Brian et al. reported that there were 294,000 pneumococcal deaths and 29,500 Hib deaths in HIV-uninfected children aged 1–59 months in 2015 globally [37]. The widespread use of pneumococcal and Hib vaccine has dramatically reduced pneumococcal and Hib cases and deaths. However, the implementation rates for both vaccines are relatively low in China (2–7%) [37, 38], and there is an urgent need to increase the vaccination rates to reduce pneumococcal and Hib disease burden in China.

Among children hospitalized for the virus, RSV-positive children contributed to a higher burden of disease, with higher rates of ICU admission, longer hospital stay and higher hospitalization costs compared with those infected by other respiratory viruses, as previously reported [39,40,41,42]. Children with RSV infection had a 14-fold increased risk of severe pneumonia [8], and approximately 45% of hospital admissions and in-hospital deaths due to RSV infection occurring in children < 6 months old [43]. In addition, despite low detection rates in children, K. pneumoniae was detected more frequently in severe pneumonia and had the highest rate of ICU admission and hospital charges. The burden of disease was also higher in hospitalized children < 6 months of age than in children aged 6–24 months, which may be related to the higher rate of RSV [43] and K. pneumoniae in children < 6 months old [44].

There were some limitations in our study. First, this was a retrospective study of children hospitalized with pneumonia in a single center in Xiamen. Second, this study was confined in partial pathogens and more pathogens such as human rhinovirus, coronavirus, human metapneumovirus, human bocavirus, cytomegalovirus, Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Legionella spp., Salmonella spp., etc., should be considered and identified in future studies [8, 45]. Third, we cannot exclude the presence of viral and bacterial coinfection, nor can we establish a causal relationship between bacteria and pneumonia. In addition, Streptococcus pneumonia, H. influenza, M. catarrhalis, S. aureus and E. coli, etc., may be part of normal flora or colonizers in the upper respiratory tract, so bacteria detected in this study may not be the cause of pneumonia [46, 47]. Additionally, nasal swabs were detected by direct immunofluorescence rather than RT-PCR, which has better sensitivity and specificity.

Conclusions

The burden of hospitalization for children with pneumonia was highest among infants < 6 months old in Xiamen. Among children < 2 years of age hospitalized with pneumonia in Xiamen, RSV was the most common respiratory virus, while H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae remained the predominant bacterial pathogens detected. Considering the low implementation rate of vaccines against pneumococcal and Hib pneumonia in China, there is an urgent need to increase both vaccination rates to reduce pneumococcal and Hib disease burden.

References

Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3027–35.

McAllister DA, Liu L, Shi T, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of pneumonia morbidity and mortality in children younger than 5 years between 2000 and 2015: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e47–57.

Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):835–45.

Yun KW, Wallihan R, Juergensen A, Mejias A, Ramilo O. Community-acquired pneumonia in children: myths and facts. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(102):S54–7.

Ruuskanen O, Lahti E, Jennings LC, Murdoch DR. Viral pneumonia. The Lancet. 2011;377(9773):1264–75.

Mclntosh K. Community-acquired pneumonia in children. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):429–37.

O’Brien KLWL, Watt JP, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902.

O’Brien KL, Baggett HC, Brooks WA, et al. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. The Lancet. 2019;394(10200):757–79.

Levine OS, Liu G, Garman RL, Dowell SF, Yu SG, Yang YH. Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae as causes of pneumonia among children in Beijing, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6(2):165–70.

Sung RYT, Chan RCK, Tam JS, Oppenheimer SJ. Epidemiology and etiology of pneumonia in children in Hong-Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(5):894–6.

Zhu Y, Zhu X, Deng M, Wei H, Zhang M. Causes of death in hospitalized children younger than 12 years of age in a Chinese hospital: a 10 year study. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):8.

Ning G, Wang X, Wu D, et al. The etiology of community-acquired pneumonia among children under 5 years of age in mainland China, 2001–2015: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2742–50.

Zhao YJ, Lu RJ, Shen J, Xie ZD, Liu GS, Tan WJ. Comparison of viral and epidemiological profiles of hospitalized children with severe acute respiratory infection in Beijing and Shanghai, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4385-5.

Chen JY, Hu PW, Zhou T, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of acute respiratory tract infections among hospitalized infants and young children in Chengdu, West China, 2009–2014. BMC Pediatr. 2018;5:18.

Wang HP, Zheng YJ, Deng JK, et al. Prevalence of respiratory viruses among children hospitalized from respiratory infections in Shenzhen, Chian. Virol J. 2016;8:13.

Boyce TG, Mellen BG, Mitchel EF Jr, et al. Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in medicaid. J Pediatr. 2000;137:865–70.

Shaw CA, Ciarlet M, Cooper BW, et al. The path to an RSV vaccine. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3(3):332–42.

Chu HY, Steinhoff MC, Magaret A, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus transplacental antibody transfer and kinetics in mother-infant Pairs in Bangladesh. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(10):1582–9.

Munoz FM. Influenza virus infection in infancy and early childhood. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2003;4(2):99–104.

Eick AA, Uyeki TM, Klimov A, et al. Maternal influenza vaccination and effect on influenza virus infection in young infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):104–11.

Neuzil KM, Mellen BG, Wright PF, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(4):225–31.

Weinberg AFMTS, Ishida MA, Souza MC. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay determination of anti-adenovirus antibodies in an infant population. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1989;31:336–40.

Thorner AR, Vogels R, Kaspers J, et al. Age dependence of adenovirus-specific neutralizing antibody titers in individuals from sub-Saharan Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(10):3781–3.

Yu B, Wang Z, Dong JN, et al. A serological survey of human adenovirus serotype 2 and 5 circulating pediatric populations in Changchun, China, 2011. Virol J. 2012;23(9):287.

Kelly JH. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(2):242–64.

Wang F, Zhao LQ, Zhu RN, et al. Parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3 in pediatric patients with acute respiratory infections in Beijing during 2004 to 2012. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128(20):2726–30.

Duijts L, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Moll HA. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in infancy. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e18-25.

Duijts L, Ramadhani MK, Moll HA. Breastfeeding protects against infectious diseases during infancy in industrialized countries. A systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;5(3):199–210.

Abu-Raya B, Maertens K, Edwards KM, Omer SB, Englund JA, Flanagan KL, et al. Global perspectives on immunization during pregnancy and priorities for future research and development: an international consensus statement. Front Immunol. 2020;24(11):1282.

Thwaites CL, Beeching NJ, Newton CR. Maternal and neonatal tetanus. Lancet. 2015;385(9965):362–70.

Abu Raya B, Edwards KM, Scheifele DW, Halperin SA. Pertussis and influenza immunisation during pregnancy: a landscape review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(7):e209–22.

Esposito S, Principi N. European society of Clinical microbiology and infectious diseases Escmid Vaccine Study Group. Evasg Strategies to develop vaccines of pediatric interest. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16(2):175–86.

Nascimento-Carvalho AC, Ruuskanen O, Nascimento-Carvalho CM. Comparison of the frequency of bacterial and viral infections among children with community-acquired pneumonia hospitalized across distinct severity categories: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;22:16.

Saha SK, Schrag SJ, El Arifeen S, et al. Causes and incidence of community-acquired serious infections among young children in south Asia (ANISA): an observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2018;392(10142):145–59.

Bhuyan GS, Hossain MA, Sarker SK, et al. Bacterial and viral pathogen spectra of acute respiratory infections in under-5 children in hospital settings in Dhaka city. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0174488.

Bhuiyan MU, Snelling TL, West R, et al. Role of viral and bacterial pathogens in causing pneumonia among Western Australian children: a case-control study protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020646.

Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(7):e744–57.

Boulton ML, Ravi NS, Sun X, Huang Z, Wagner AL. Trends in childhood pneumococcal vaccine coverage in Shanghai, China, 2005–2011: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2016;2(16):109.

Kwofie TB, Anane YA, Nkrumah B, Annan A, Nguah SB, Owusu M. Respiratory viruses in children hospitalized for acute lower respiratory tract infection in Ghana. Virol J. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-9-78.

Shafik CF, Mohareb EW, Yassin AS, et al. Viral etiologies of lower respiratory tract infections among Egyptian children under five years of age. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;13(12):350.

Tregoning JS, Schwarze J. Respiratory viral infections in infants: causes, clinical symptoms, virology, and immunology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):74–98.

Hervas D, Reina J, Yanez A, del Valle JM, Figuerola J, Hervas JA. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute bronchiolitis in children: differences between RSV and non-RSV bronchiolitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(8):1975–81.

Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):946–58.

Ejaz H, Wang N, Wilksch JJ, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae from hospitalized children Pakistan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(11):1872–5.

Barger-Kamate B, Deloria Knoll M, Kagucia EW, Prosperi C, Baggett HC, Abdullah Brooks W, et al. Pertussis-associated pneumonia in infants and children from low- and middle-income countries participating in the PERCH study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):S187–96.

Baggett HC, Watson NL, Deloria Knoll M, Brooks WA, Feikin DR, Hammitt LL, et al. Density of upper respiratory colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae and its role in the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia among children aged <5 years in the PERCH study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S317–27.

Park DE, Baggett HC, Howie SRC, Shi Q, Watson NL, Brooks WA, et al. Colonization density of the upper respiratory tract as a predictor of pneumonia-Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pneumocystis jirovecii. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_3):S328–36.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff who managed the patient records in Xiamen Maternal and Child Health Hospital. We also thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This work and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were supported by Y. Zhou, Xiamen Science and Technology Major Project (3502Z20171006), the National Key Program for Infectious Disease of China (2018ZX10101001-002) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81161120419 and 81401668).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Yu-Lin Zhou, Ying-Ying Su, Zi-Zheng Zheng and Jun Zhang contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Xin-Yi Zheng, Hai-Xia Zhang, Xiao-Man Zhou, Xin-Zhu Lin and Yong-Peng Sun. Yong-Peng Sun, Ying-Ying Su and Yu-Lin Zhou drafted manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Disclosures

Yong-Peng Sun, Xin-Yi Zheng, Hai-Xia Zhang, Xiao-Man Zhou, Xin-Zhu Lin, Zi-Zheng Zheng, Jun Zhang, Ying-Ying Su and Yu-Lin Zhou have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Maternal and Child Health Hospital and the School of Public Health of Xiamen University and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Medical records were de-identified with all personally identifiable information removed. The patient’s parent, guardian or legal representative provided authorization to the investigator to use and/or disclose personal and/or health data.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, YP., Zheng, XY., Zhang, HX. et al. Epidemiology of Respiratory Pathogens Among Children Hospitalized for Pneumonia in Xiamen: A Retrospective Study. Infect Dis Ther 10, 1567–1578 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00472-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00472-0