Abstract

Introduction

Overuse of medication to treat migraine attacks can lead to development of a new type of headache or significant worsening of pre-existing headache, known as medication overuse headache. However, data concerning the burden of medication overuse (MO) in migraine are limited. This study aimed to assess the humanistic burden of MO in individuals with migraine from five European countries.

Methods

Data are from the 2020 National Health and Wellness Survey—a cross-sectional, population-based survey conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Data were included from adults (≥ 18 years) with a self-reported diagnosis of migraine and at least one migraine attack and one headache in the past 30 days. MO was defined as (i) use of simple analgesics/over-the-counter medications on ≥ 15 days/month; or (ii) use of migraine medication, including combination analgesics, on ≥ 10 days/month. Humanistic burden of MO was assessed using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12v2), EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Levels (EQ-5D), Short-Form 6-Dimensions (SF-6D), and Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS). The association of MO with humanistic burden was evaluated using generalized linear models adjusted for potential confounders in the full migraine population and in subgroups defined by headache frequency (monthly headache days [MHDs] 1–3, 4–7, 8–14, or ≥ 15).

Results

Among individuals with migraine, humanistic burden (SF-12v2, SF-6D, EQ-5D, and MIDAS) was higher in individuals who reported MO (n = 431) versus no MO (n = 3554), even after adjustment for confounding variables (p < 0.001 for all measures). MIDAS and EQ-5D scores were higher in individuals with MO than without, at all levels of headache frequency. For SF-12v2 and SF-6D, differences between groups with/without MO were seen only at lower levels of headache frequency (MHD 1–3 and 4–7).

Conclusion

Among people with migraine, those who report MO face a greater humanistic burden than those without MO, irrespective of headache frequency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Medication overuse by people with headaches can lead to various problems, including medication overuse headache. However, data concerning the burden of medication overuse in migraine are limited. |

This study evaluated the humanistic burden of medication overuse in people with migraine in Europe. |

What was learned from the study? |

The results show that among people with migraine, those who report medication overuse face a greater humanistic burden (lower health-related quality of life and health status, and greater migraine-related disability) than those who do not report medication overuse, irrespective of headache frequency. |

Further analysis is required to better understand the factors underlying medication overuse—a potentially avoidable condition—in order to provide more effective pain management for individuals with migraine. |

Introduction

The 2019 Global Burden of Disease study ranked headache disorders as the third highest cause of global disability worldwide (expressed as years lived with disability, YLDs) and the leading cause of disability among people younger than 50 years [1, 2]. Migraine accounted for 88.2% of this burden, being responsible for 42.1 million YLDs (4.8% of total YLDs) in 2019 [3].

In some cases, a person experiencing migraines will have insufficient relief with their prescribed acute medication, leading them to increase their use of that medication. The International Classification of Headache Disorders defines medication overuse (MO) as the use of acute or symptomatic headache medication (e.g., triptans, opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories) on ≥ 10 or ≥ 15 days per month, depending on the medication [4]. Such frequent use not only presents a potential economic challenge to the patient and/or medical provider but can also lead to various other problems such as the emergence of medication overuse headache (MOH) on top of the pre-existing primary headache [4,5,6]. Across Europe, migraine (with or without concurrent tension-type headache) has been reported as the underlying primary headache disorder in almost 90% of cases of MOH [7], and MOH has been reported as affecting as many as 65% of individuals with chronic headache/migraine [8, 9]. According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study, headache resulting from MO was responsible for 15% of YLDs due to migraine, alongside symptomatic migraine [1, 3]. In addition, the overuse of medication itself often requires treatment, with education/counseling, acute drug withdrawal (in hospital for some patients), or starting/changing preventive medication recommended by European guidelines for managing MOH [6].

Although there is a paucity of recent data on the cost burden of headache disorders, in 2008/2009 the large-scale Eurolight project (including more than 8000 adult respondents from the general population or visiting GPs for any reason, across multiple European countries) estimated that migraine and MOH accounted for 64% and 21% of the total annual cost of headache disorders (€173 billion across all 27 European counties), respectively, with indirect costs (e.g., absenteeism, work productivity) contributing more than 90% of this total in both cases [10]. Eurolight also highlighted that the high personal burden of headache disorders (including impact on partners and children) was greatest in individuals with MOH [11]. Some individuals with migraine have a lower headache frequency but achieve this level as a result of high use of acute medication. These individuals are at risk of disease progression and becoming caught in a vicious cycle of MO and chronification [12, 13]. There is still a need to understand the burden of MO in individuals with differing headache frequencies, and much to learn about both the economic and humanistic costs of MO in migraine.

The aim of the current study was to assess the humanistic burden of MO in people with migraine in terms of health status, quality of life, and disability, in five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK).

Methods

Data for this study were retrieved from the 2020 European National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS)—a cross-sectional, population-based survey of 62,319 individuals in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK.

Regarding ethical compliance, the European NHWS protocol and questionnaire were reviewed by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and met the exemption requirements under FDA 21 CFR 56.104 and 45CFR46.104(b)(2): (2) Tests, Surveys, Interviews (IRB # 19-KANT-204). All respondents provided their informed consent electronically.

Study Design and Participants

The 2020 NHWS is a self-administered, internet-based questionnaire survey (from Cerner Enviza, formerly Kantar Health) designed to capture the health of the general population. Participants were recruited to a consumer panel through opt-in e-mails, co-registration with panel partners, e-newsletter campaigns, website banner placements, and affiliate networks. All panelists explicitly agreed to be a panel member, registered with the panel through a unique e-mail address, and completed an in-depth demographic registration profile; they were provided country-specific, fair-market-value incentives. Respondents complete the NHWS questionnaire only once in a given year. A quota-based sampling procedure, stratified by sex and age for each country sampled, was implemented for the 2020 NHWS to ensure that the demographic composition was representative of each country’s population.

The current analysis included data from participants in the 2020 NHWS who were aged ≥ 18 years and had experienced a migraine in the past 12 months, self-reported to have been diagnosed as a migraine by a physician, and had at least one migraine attack and one headache in the past 30 days. Only patients qualifying as having “migraine” as defined were included in this analysis, to facilitate analysis of MO in this population. This included people reporting “normal” headaches and migraines (the majority of head pain records) and those reporting a physician diagnosis of migraine (Fig. 1) and did not include other headache disorders.

The respondents were grouped by headache frequency [monthly headache days (MHDs) 1–3, 4–7, 8–14, or ≥ 15] and the presence of MO. MO was defined according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders: use of simple (non-opioid) analgesics/over-the-counter medications for migraine on ≥ 15 days/month, or use of migraine medication (including combination analgesics) on ≥ 10 days/month [14]. Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material provides further details of simple analgesics and migraine medications.

Study Assessments

The humanistic burden of MO in the NHWS population was assessed using several measures of health- and migraine-related quality of life and disability. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the revised 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (Version 2; SF-12v2) [15], which is scored from 0 to 100 (with higher scores indicating a better health status) and includes two summary scores—the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS). PCS and MCS scores are adjusted to the US population and have a mean of 50, with 10 points corresponding to a standard deviation of 1; scores can be interpreted relative to this population average [16]. Health status was assessed using the Short-Form 6-Dimensions (SF-6D) index and the EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Levels (EQ-5D-5L) utility index, both scored from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health state) [17, 18]. EQ-5D-5L scores were calculated using country-specific value sets. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire was used to quantify migraine-related disability over a 3-month period, reflecting the number of days reported as missing or with reduced work/home/social productivity [19]. MIDAS scores are grouped into four categories: little to no disability (0–5), mild disability (6–10), moderate disability (11–20), and severe disability (≥ 21). In the present analysis, a MIDAS score of ≥ 11 was used to indicate moderate-to-severe disability.

Statistical Analysis

All assessment data, including demographics, were summarized using descriptive techniques. Summary statistics are presented for continuous variables, and counts and percentages are presented for categorical and binary variables. Prevalence estimates for MO were weighted according to country-specific age and sex distributions. Weighted estimates were projected against the total populations from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK using NHWS post-stratification sampling weights calculated from the 2019/2020 International Data Base of the US Census Bureau and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Programming of the survey required respondents to respond to all the items presented to them, and all respondents completed the endpoints relevant to them, including the primary outcome measure (EQ-5D-5L), SF-12v2, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire, and healthcare resource utilization items. Missing data was minimized by providing “don’t know” or “decline to answer” as options; however, there was a small amount of missing data that was not expected to be missing at random. Complete case analysis was used in multivariable modeling.

Bivariate analyses were used to compare participant demographics/characteristics and all outcome variables according to MO (with/without). For categorical variables, chi-square tests were used to determine the level of significance, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous variables. A Bonferroni correction was used to limit the risk of type 1 errors due to multiple comparisons (three comparisons: MHD 1–3 vs MHD 4–7; MHD 8–14 vs MHD 4–7, and MHD ≥ 15 vs MHD 4–7) and the new significance threshold was calculated as 0.05/3 = 0.017. For the above multiple comparisons to achieve statistical significance, the p value for each comparison was required to be ≤ 0.017. MO and headache frequency are highly correlated, and both are potential strong drivers of burden. To achieve a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between headache frequency, MO, and burden, bivariate analyses investigating the association between MO and measures of humanistic burden were performed for subgroups defined by headache frequency.

In multivariable analyses, generalized linear mixed models were used to examine the association between MO and humanistic burden in the full migraine population. A random intercept was used to account for clustering within country. Models examined the incremental burden of MO compared with participants without MO (reference group).

The distribution used for the models depended on the outcome variable—the best approach for each variable was determined after reviewing the distributions of these outcomes. Model diagnostics were assessed to confirm appropriate use of a given distribution to model an outcome. Generalized linear mixed models with normal and negative binomial distributions were used, similar to previous studies [20,21,22].

Multivariable models were adjusted for a priori confounders of age, sex, education, income, employment status, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Other potential confounders, including marital status, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise behavior, and country of residence, were included as deemed appropriate, according to the bivariate findings and the medical literature. Adjusted estimates, standard errors, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p values were calculated for each dependent variable.

All data management and analyses were performed by Cerner Enviza (North Kansas City, MO, USA).

Results

Study Population

A total of 3985 respondents (6.4% of the full survey population) were included in this study analysis (France, n = 1020; Germany, n = 779; Italy, n = 900; Spain, n = 595; UK, n = 691) (Fig. 1). Of these, MO was reported in 431 individuals, giving a weighted prevalence of MO of 10.71% (95% CI 10.69–10.72).

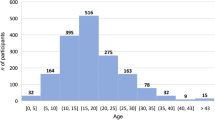

The demographics and health and clinical characteristics of this European migraine population are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Overall, 431 people met the study criteria for MO; 3554 respondents did not. The majority of respondents were aged 18–69 years, with a relatively similar distribution between the with and without MO groups for the different age subcategories. Approximately 71% of respondents were female. Across both populations, most (54–56%) respondents identified as being middle-income households, and the majority (59–66%) were in employment (Table 2). The greatest proportion of respondents lived in France (n = 1020) and fewest in Spain (n = 595), with the rate of MO ranging from 7.2% (Italy; n = 65/900) to 15.5% (UK; n = 107/691) (Table 1).

Bivariate analysis showed that migraine respondents with MO were less likely to use alcohol, and undergo vigorous exercise, and more likely to be unemployed, have a higher BMI, to smoke, and to have more comorbidities, compared with migraine respondents without MO (Table 2).

Humanistic Burden of Medication Overuse

The humanistic burden of migraine on the SF-12v2, EQ-5D, and SF-6D indices was significantly higher in those who reported MO than in those who did not, even after adjustment for confounding variables (multivariable analysis) (Fig. 2). MO was associated with significantly lower health-related quality of life (SF-12, both mental and physical subscores; Fig. 2a), lower overall health status (EQ-5D and SF-6D index scores; Fig. 2b), when compared with individuals without MO (all p < 0.001). Individuals with migraine who reported MO also had a significantly higher probability of experiencing moderate-to-severe migraine-related disability (defined as MIDAS score ≥ 11) than those who did not report MO (Fig. 3).

Humanistic burden of migraine measured by adjusteda mean a EQ-5D and SF-6D indices (multivariable analysis) and b SF-12v2 (MCS and PCS). aAdjusted for age, sex, education, income, employment status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, body mass index, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use, and exercise. Bars represent upper and lower CIs based on the standard error. CI, confidence interval; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimensions; MCS, mental component summary; MO, medication overuse; PCS, physical component summary; SF-6D, Short-Form 6-Dimensions; SF-12v2 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (Version 2)

Adjusted probabilitya of experiencing moderate-to-severe migraine-related disability (MIDAS ≥ 11) by medication overuse (multivariable analysis). aAdjusted for age, sex, education, income, employment status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, body mass index, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use, and exercise. Bars represent upper and lower CIs based on the standard error. CI confidence interval, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, MO medication overuse

Findings from the (unadjusted) bivariate analyses indicated slightly larger differences among MO groups compared to what was seen in the adjusted analyses, suggesting some confounding of the investigated relationship (Table S2 in the electronic supplementary material).

Humanistic Burden of Medication Overuse According to Headache Frequency

The percentage of respondents with MO increased with increasing number of headache days, occurring overall in 3.7% of respondents with 1–3 MHDs up to 31.7% of those experiencing ≥ 15 MHDs (Fig. S1 in the electronic supplementary material).

Worse outcomes for the MO groups (versus the no MO groups) were seen at lower levels of headache frequency (1–3 and 4–7 MHDs) in measures of health-related quality of life (SF-12v2 MCS and PCS) (Fig. 4a, b) and health status (SF-6D; Fig. 4c). Health status, as measured by the EQ-5D, was lower in individuals reporting MO versus no MO across all headache frequencies (Fig. 4d).

Medication overuse and the humanistic burden of migraine by headache frequency (multivariable analysis), as measured by mean a SF-12 MCS, b SF-12 PCS, c SF-6D index, d EQ-5D index, and e MIDAS scores. CI, confidence interval; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimensions; MCS, mental component summary; MO, medication overuse; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment; PCS, physical component summary; SF-6D, Short-Form 6-Dimensions; SF-12, 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

Irrespective of headache frequency, individuals with migraine who reported MO experienced significantly greater migraine-related disability (MIDAS) than those who did not (Fig. 4e).

Discussion

Based on data from a European cross-sectional, population-based survey, our study showed that among people with migraine, those who report MO face a greater humanistic burden than those without MO. This was reflected in greater migraine-related disability (assessed using MIDAS) and reduced health-related quality of life (SF-12v2) and overall health status (SF-6D, EQ-5D-5L). Notably, the significant reduction in overall health status and increase in migraine-related disability with MO (compared with without MO) was observed across all levels of headache frequency, from 1–3 to ≥ 15 MHDs. Thus, MO—and the associated detrimental effects on health and disability—occurred even in individuals with a low headache frequency. MO among individuals with a low headache frequency may be due to a “more or less” controlled condition, but where a high level of medication is needed to achieve this. It is also possible that these individuals take medications for other conditions than their headaches, as suggested below. However, our analyses also showed that MO occurred in less than 4% of participants with 1–3 MHDs compared with 32% of individuals with ≥ 15 MHDs. These findings may reflect a vicious cycle of MO [12]. In this context, it has previously been shown that MO is associated with a risk of progression from episodic to chronic migraine [13]. As such, people with MO may be those with the most urgent need for effective migraine-preventive treatment to halt the vicious cycle and reverse disease progression.

Examining the demographics of the population in the current study using unadjusted analyses showed that several variables (which were subsequently adjusted for in multivariable analyses) had a very strong link to MO. Compared with participants who did not overuse medication, those with MO were less likely to be employed, rarely consume alcohol, or engage in vigorous exercise, and more likely to smoke, have obesity, and report comorbid conditions. As this was a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to determine whether these factors are a consequence of MO or whether they are predecessors that increase the risk of MO. However, the results do suggest that MO is related to a higher humanistic burden, and that individuals with MO constitute a generally vulnerable migraine population. Individuals with a high level of comorbidities might take medications for reasons other than their migraine/headaches, and this may partly explain the higher level of comorbidity in the MO group. Interestingly, a higher level of comorbid conditions among migraine sufferers with MO compared with those without MO has been reported elsewhere [23]. Variables that did not appear to be linked to MO were age category, sex, level of education, and household income.

The unadjusted analyses revealed some country-related differences, with the greatest proportions of respondents with migraine MO living in UK (15.5%) and the lowest in Italy (7.2%). The difference could be a chance finding but could also reflect a difference in migraine prevalence between the countries and may suggest a difference in health behavior and medication usage among European countries. Stratified sampling was done to ensure demographically representative population in each individual country. For example, there could be greater reluctance of patients or physicians to treat/overtreat migraine in some countries, or other means of management (e.g., herbal remedies, dietary supplements) may be prevalent.

Another survey revealed significant differences in the treatment preferences of patients with migraine in the USA (n = 257) and Germany (n = 249)—for example, German patients were less concerned about the mode of treatment than US patients and more concerned about treatment side effects [24]. In addition, two recent European surveys reported inadequate physician education in headache disorders, which may be another contributing factor to inter-country differences and potentially to MO in general [25]. An additional survey highlighted a lack of knowledge among French neurology residents regarding headache medicine [26], while another found that almost half of Danish neurology residents perceived their training in headache disorders to be inadequate, and that the field of headache disorders was undervalued [27].

This survey-based study has several limitations. Potential selection bias means that the reported prevalence of MO in those with migraine in the current study (ca. 10%) is likely to be an underestimate, as well-functioning patients are more likely to respond to a survey questionnaire than poorly functioning patients (i.e., those with MO). As a general health survey, the NHWS reported data on migraine prevalence and the characteristics of people with migraine, but it was not constructed to screen specifically for MO within this subpopulation—a larger migraine population would have been required for this. The cross-sectional design of the study means that it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between MO and headache frequency. The study was based on participant self-reported data, which could have influenced the findings. In particular, a potential reporting bias may have been created as a result of respondents having difficulty distinguishing between headache and migraine, because a “physician diagnosis” of migraine was self-reported and there was no definition for type of migraine provided in the survey. The criterion of “the past 30 days” increases the likelihood that the participant was acutely experiencing a migraine, which should have contributed to a more relevant population of patients with migraine compared with having included, for example, patients who have experienced a migraine at any point; however, this may have resulted in a more conservative prevalence estimate of migraine.

In addition, recall of medication use may have introduced misclassification, and there may have been underreporting of some medications associated with stigma (e.g., opioids). It was not possible to investigate the burden of pain reliever use in patients with MO associated with migraine medication, because MO was defined as overuse of either type of medication. Further, the survey was insufficiently granular to be able to understand treatment choice patterns (pain relievers being combined with, or replacing, migraine medication) or behaviors (economic or reimbursement pressures, habit, or choices based on adverse effects or the type of headache experienced). Additional research and understanding into these aspects of MO are welcome.

Strengths of the study include the population size and representativeness spanning five European countries, as well as the collection of detailed information on MO and validated measures of humanistic burden in a diverse population of individuals with varying headache frequency. Survey accessibility was also supported for older patients who may be less comfortable with online surveys: telephone recruitment was used to supplement online panel recruitment and patients could then complete the survey via telephone or online (via a web survey link emailed to them). Patients who had no access to the internet were able to complete the survey on a computer in a private center.

Conclusion

Individuals with migraine who report MO face a greater humanistic burden than those who do not report MO, irrespective of headache frequency. Further analysis is required to better understand the factors underlying this potentially avoidable condition, and so provide more effective management for all individuals with migraine.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z, Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:137.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators Group. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22.

Global Health Metrics. Migraine—level 4 cause. https://www.thelancet.com/pb-assets/Lancet/gbd/summaries/diseases/migraine.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2022.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211.

Diener HC, Dodick D, Evers S, et al. Pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of medication overuse headache. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:891–902.

Diener HC, Antonaci F, Braschinsky M, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on the management of medication-overuse headache. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1102–16.

Find NL, Terlizzi R, Munksgaard SB, et al. Medication overuse headache in Europe and Latin America: general demographic and clinical characteristics, referral pathways and national distribution of painkillers in a descriptive, multinational, multicenter study. J Headache Pain. 2015;17:20.

Straube A, Pfaffenrath V, Ladwig KH, et al. Prevalence of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache in Germany—the German DMKG headache study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:207–13.

Colás R, Muñoz P, Temprano R, Gómez C, Pascual J. Chronic daily headache with analgesic overuse: epidemiology and impact on quality of life. Neurology. 2004;62:1338–42.

Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ, et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:703–11.

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, et al. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:31.

Tepper SJ, Tepper DE. Breaking the cycle of medication overuse headache. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77:236–42.

Buse DC, Greisman JD, Baigi K, Lipton RB. Migraine progression: a systematic review. Headache. 2019;59:306–38.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker D, Gandek B, Mariush M. User’s manual for the SF-12v2 health survey. 2nd ed. QualityMetric; 2009.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 2nd ed. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–92.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–36.

Stewart W, Lipton R, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Sawyer J. Reliability of the migraine disability assessment score score in a population-based sample of headache sufferers. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:107–14.

DiBonaventura Md, Gupta S, McDonald M, Sadosky A. Evaluating the health and economic impact of osteoarthritis pain in the workforce: results from the National Health and Wellness Survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:83.

Goren A, Liu X, Gupta S, Simon TA, Phatak H. Quality of life, activity impairment, and healthcare resource utilization associated with atrial fibrillation in the US National Health and Wellness Survey. PLoS One. 2013;8: e7126.

Gupta S, Goren A, Phillips AL, Stewart M. Self-reported burden among caregivers of patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14:179–87.

Schwedt TJ, Buse DC, Argoff CE, et al. Medication overuse and headache burden: results from the CaMEO study. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11:216–26.

Hubig LT, Smith T, Chua GN, et al. A stated preference survey to explore patient preferences for novel preventive migraine treatments. Headache. 2022;62:1187–97.

Ashina M, Katsarava Z, Do PT, et al. Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet. 2021;397:1485–95.

Beltramone M, Redon S, Fernandes S, Ducros A, Avouac A, Donnet A. The teaching of headache medicine in France: a questionnaire-based study. Headache. 2022;62:1177–86.

Kristensen MGH, Do TP, Pozo-Rosich P, Amin FM. Interest in and exposure to headache disorders among neurology residents in Denmark: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022;146:568–72.

Acknowledgements

Data for this study were retrieved from the National Health and Wellness (NHWS) database of Cerner Enviza, formerly Kantar Health. Statistical analyses were conducted by Cerner Enviza, led by Dena Jaffe, Senior Evidence Generation Lead.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript were provided by Colin Griffin and Juliet George for Piper Medical Communications Ltd, funded by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Funding

The study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Agnete Skovlund Dissing, Xin Ying Lee, Ole Østerberg, Lene Hammer-Helmich contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Cerner Enviza, formerly Kantar Health, under the direction and supervision of Agnete Skovlund Dissing. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Agnete Skovlund Dissing and all authors commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

At the time of study completion, Agnete Skovlund Dissing, Xin Ying Lee, Ole Østerberg, Lene Hammer-Helmich were all employees of H. Lundbeck A/S.

Ethical Approval

The survey protocol and questionnaire were reviewed by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and met the exemption requirements under FDA 21 CFR 56.104 and 45CFR46.104(b)(2): (2) Tests, Surveys, Interviews (IRB # 19-KANT-204). All respondents provided their informed consent electronically.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dissing, A.S., Lee, X.Y., Østerberg, O. et al. Burden of Medication Overuse in Migraine: A Cross-sectional, Population-Based Study in Five European Countries Using the 2020 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS). Neurol Ther 12, 2053–2065 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00545-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00545-x