Abstract

In Taiwan, the number of patients being treated for depression has been increasing over recent decades, but there remain some key unmet needs for these patients. One issue is the low rate of help-seeking, which may be at least partially attributable to the stigma of depression in Asian societies. Stigma also contributes to underdiagnosis, because stigmatised patients may emphasise somatic symptoms (e.g. lethargy/fatigue, sleep disorders or changes in appetite), fearing how they will be perceived if they discuss psychological symptoms with their physician. Underdiagnosis may also result from cross-cultural differences, because assessment scales and screening tools are usually developed in Western populations and may not have the same validity in Asian patients. Depression in Taiwan appears to be undertreated, with a high rate of suboptimal antidepressant dosages and inadequate duration of therapy. Patients may discontinue treatment earlier than recommended for a number of reasons related to their own beliefs about treatment, their relationship with their physicians, or the effects of the medication (adverse effects, slow onset of effect, or lack of effect on comorbid symptoms). Moreover, frequently there is discordance between how patients and physicians define treatment success in depression. Patients are more likely to achieve a benefit from treatment which remains persistent when physicians and patients are closely aligned on treatment goals. To better understand the experiences, preferences and attitudes of patients with depression in Taiwan, the Target Antidepressant Initiation choice to unLock positive patient Outcomes and Response (TAILOR) survey was conducted in 340 adult outpatients receiving treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). The results of the TAILOR survey highlight the personal and perceived stigma of depression, current barriers to seeking help and maintaining treatment, and opportunities to improve shared decision-making, medication adherence and clinical outcomes for Taiwanese patients with MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The number of individuals being treated for depression in Taiwan is increasing. |

However, there remain some key unmet needs: low rate of help-seeking, underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression, and early discontinuation of antidepressant therapy. |

Stigma associated with depression and antidepressant therapy may contribute to these issues, especially if patients emphasise somatic symptoms during consultations. |

There is often discordance between physicians and patients about the goals of treatment, so improved understanding of the concerns of patients with depression is needed. |

The results of the TAILOR survey provide important insights into the experiences, preferences and attitudes of Taiwanese patients with depression, and highlight opportunities to enhance shared decision-making between physicians and patients, promote medication adherence and improve clinical outcomes. |

Introduction

Data indicate that the number of patients seeing a healthcare provider for depression in Taiwan has increased by approximately 25% in the decade between 2007 and 2016 [1]. Nevertheless, undiagnosed depression remains a major community problem around the world, with data suggesting that, for every patient diagnosed with depression, there is another in the community who has yet to be diagnosed [2]. Moreover, when patients are diagnosed, only about one in five receives adequate treatment according to World Mental Health Surveys [3].

Unmet needs among patients with depression in Taiwan include a low rate of help-seeking, underdiagnosis, undertreatment and early discontinuation of treatment. The aim of the current article is to examine these unmet needs in more detail and why it is important to know what patients with depression want from treatment, as well as to introduce a new survey that is investigating the experiences, preferences and attitudes of patients with depression in Taiwan.

Unmet Needs in Treatment of Depression in Taiwan

Low Rate of Help-Seeking

While there is wide acceptance of psychiatry in Taiwan, a low rate of help-seeking for depression has been reported [4], along with a high degree of stigma associated with receiving treatment for depression [5]. This is concerning because patients may be reluctant to seek help if they think that others will view them negatively if they receive treatment for depression. While data from Asia on this issue are lacking, studies in the African American community in the US, which also reports high levels of stigma associated with depression, suggest that stigmatisation is a major barrier to patients with depression seeking medical treatment [6]. Stigma may be a particular barrier to visiting a psychiatric or mental health service provider, since the reason for a visit to a primary care physician can be easily disguised [7]. However, according to one meta-analysis, primary care physicians accurately identify depression in only about half of the depressed patients who attend consultations [8].

Underdiagnosis

In the meta-analysis by Mitchell and colleagues referred to above, primary care physicians are able to accurately rule out depression in a high proportion of patients who do not have the condition, but are less able to accurately identify depression in those who do [8]. There may be a number of reasons for this. First, because stigmatised patients are afraid of how they will be perceived, they may emphasise somatic symptoms of depression (e.g. lethargy/fatigue, sleep disorders or changes in appetite) rather than psychological symptoms, and this can lead to misdiagnosis [6, 9]. Indeed, the Study on Aspects of Asian Depression found that Asian patients with depression reported sleep disorders at the same frequency as they reported feelings of sadness [10], and separate research from Asia described a high rate of somatic pain (51%) among depressed patients [11].

Underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of depression may be a particular concern for patients who are experiencing somatic symptoms, since data from Taiwan have shown that patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) or generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) who are experiencing somatic symptoms have more severe underlying anxiety than those without somatic symptoms [12]. The management of anxiety with somatisation is important in this context, since inadequate management can negatively affect the prognosis of MDD and/or GAD [12].

Another potential reason for underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of depression in Asia is because most of the screening/assessment tools for depression were developed in Western (Caucasian) populations and in English, and therefore may have limited validity in other populations as a result of linguistic, semantic or cultural differences [13]. For example, a study in a US population of Latino depressed patients found that they were highly unlikely to endorse Question 15 on the Beck Depression Inventory that related to their ability/motivation to work, irrespective of their depression severity [14]. The authors ascribed this finding to the work ethic of the Latino community, as well as the sometimes tenuous low-wage employment and workplace discrimination they experience [14].

While the overall diagnoses of depression are low in Taiwan, there is a notable difference between genders, with females around twice as likely to be diagnosed compared with males [15]. Although females are more likely to contact healthcare services, major depression remains largely underdiagnosed for both genders, which may reflect a cultural bias against confronting emotional/psychological problems. Of note, initial contact between the patient and healthcare professional appears to constitute the primary bottleneck of depression care in Taiwan [16].

Undertreatment

A 10-year survey of depression treatment patterns in Taiwan, based on the National Health Insurance (NHI) database, showed that 80–85% of patients who see a health professional for depression receive pharmacotherapy [1]. However, this treatment is not always adequate. For example, in about 40% of patients, the average antidepressant dose is lower than the minimal recommended dose [1], and only 30–40% of patients receive antidepressant therapy for at least 60 days [1]. While the adequacy of treatment improved between 2007 and 2016, fewer than 30% of depressed patients in Taiwan in 2016 were receiving treatment at recommended doses for the required duration [1].

Access to psychotherapy is limited in Taiwan because this treatment modality is not fully covered by the Taiwanese NHI program, and therefore the combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is rarely used [1].

Early Discontinuation

As described above, a high proportion of Taiwanese patients do not persist with antidepressant pharmacotherapy for ≥ 60 days [1], with < 10% continuing initial antidepressant monotherapy for ≥ 180 days [17]. The reasons for the low rate of persistence in Taiwan are not known, but they are likely similar to those reported in the West, and may encompass factors associated with the patient, physician or treatment (Table 1) [18, 19]. Effective communication between the physician and patient is key to achieving good adherence and persistence [18, 19]. This means obtaining a thorough understanding of the patient’s concerns and goals of treatment. A study in Belgium reported a disconnect between what physicians and patients considered to be important in obtaining remission from depression [20]. In this study, patients and physicians were asked to rank the importance of 51 different parameters according to the extent to which those parameters defined the cure from depression. The parameters were taken from six validated scales used to assess depression severity: the Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression subscale; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-anxiety subscale; the Patient Health Questionnaire-Somatic Symptom severity subscale; the Positive And Negative Affect Schedule-Positive Affect subscale; the Sheehan Disability Scale; and the Abbreviated World Health Organization QoL scale—psychological and social subscales. For physicians, the parameters that ranked highest in their definition of treatment success related to negative feelings, lack of pleasure/interest, and disruptions to social/leisure activities. However, patients ranked other parameters more highly, including the extent to which life is meaningful, their enjoyment of life and their satisfaction with themselves (Table 2) [20]. For example, patients ranked the following parameters first and second in their definition of cure: (1) to what extent life is meaningful, and (2) how much do you enjoy life; whereas these parameters were ranked as ninth and eighth, respectively, by physicians [20]. Moreover, these researchers found that the discordance between patients’ and physicians’ definitions of what was important in curing depression had a negative effect on clinical outcomes [21]. When patients and physicians had greater alignment on the definition of cure, the patients were significantly more likely to achieve a clinical response to antidepressant therapy [21], which in turn probably affects their likelihood of persisting with treatment [18, 19].

Taiwan’s TAILOR Survey

One strategy to address the unmet needs of patients with depression is to involve them in decisions regarding their treatment. Models of shared decision-making between physicians and patients have been successful in other fields of medicine, yet they have not been widely adopted in psychiatric practice [22]. By providing patients with evidence-based information on their diagnosis and treatment, offering therapeutic options that align with their personal preferences and treatment goals, and empowering them to be active participants in the decision-making process, shared decision-making may improve medication adherence, patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes for those with depression.

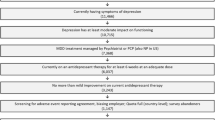

The Target Antidepressant Initiation choice to unLock positive patient Outcomes and Response (TAILOR) survey was designed to better understand the experiences, preferences and attitudes of patients with depression. In Taiwan, eight psychiatrists from seven clinics participated in the TAILOR survey from May to June 2020, and collectively recruited 340 adult outpatients receiving antidepressant therapy for MDD. The TAILOR survey received Institutional Review Board approval (IRB no. 202000335B0D001), and all patients provided informed consent. Physicians collected sociodemographic data and asked patients about their experience of depression (Table 3). Patients also completed the 12-item Short Form to assess quality of life, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and Depression Stigma Scale and the Antidepressant Compliance Questionnaire.

Unpublished results from Taiwan’s TAILOR survey are presented in Tables 4, 5 and Fig. 1. More than one-third of Taiwanese patients (126/340 patients; 37%) did not seek help at the time of their first depressive episode; the most common reason given by these patients was that they were unaware that they may have MDD. The personal and perceived stigma of depression was also a significant barrier to seeking help (Fig. 1; Table 5). Approximately half of those surveyed (171/340 patients; 50%) reported non-adherence to previous antidepressant therapy; in these patients, the most common reasons for non-adherence were the perception of being sufficiently treated (51%), side effects (35%) and the perception that treatment had been ineffective (18%). Approximately 28–40% of patients reported concerns for sleep disturbances, weight gain, emotional blunting, anhedonia and withdrawal discomfort related to antidepressant therapy. Regarding treatment preferences, 68% of patients preferred a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to manage their depression, 26% preferred pharmacotherapy alone and 5% preferred psychotherapy alone. When patients were asked to rank their involvement in treatment decisions from 1 (solely patient decision) to 7 (solely physician decision), 30% reported that treatment decisions were made solely by their doctor, and all other patients reported varying levels of involvement in the decision-making process [mean (standard deviation) ranking, 4.9 (1.8)].

Conclusions

Although there is evidence that the treatment of depression is improving in Taiwan, there are still a number of unmet needs, including underdiagnosis, undertreatment, and early discontinuation of treatment. The results of the TAILOR survey provide important insights into the experiences, preferences and attitudes of Taiwanese patients with depression, and highlight opportunities to enhance shared decision-making between physicians and patients, promote medication adherence and improve clinical outcomes.

References

Wang HH, Chang CM, Chang SS, et al. Ten-year trends in depression care in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(10):2001–11.

Williams SZ, Chung GS, Muennig PA. Undiagnosed depression: a community diagnosis. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:633–8.

Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(2):119–24.

Liao SC, Chen WJ, Le MB, et al. Low prevalence of major depressive disorder in Taiwanese adults: possible explanations and implications. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1227–37.

Lien YJ, Kao YC. Public beliefs and attitudes toward schizophrenia and depression in Taiwan: a nationwide survey. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:435–42.

Bailey RK, Blackmon HL, Stevens FL. Major depressive disorder in the African American population: meeting the challenges of stigma, misdiagnosis, and treatment disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(11):1084–9.

Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Exploring the nature of stigmatising beliefs about depression and help-seeking: implications for reducing stigma. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:61.

Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):609–19.

Tylee A, Gandhi P. The importance of somatic symptoms in depression in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(4):167–76.

Srisurapanont M, Hong JP, Tian-Mei S, et al. Clinical features of depression in Asia: results of a large prospective, cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5(4):259–67.

Lee P, Zhang M, Hong JP, et al. Frequency of painful physical symptoms with major depressive disorder in Asia: relationship with disease severity and quality of life. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(1):83–91.

Huang WL, Chen TT, Chen IM, et al. Depression and anxiety among patients with somatoform disorders, panic disorder, and other depressive/anxiety disorders in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res. 2016;241:165–71.

Kerr LK, Kerr LD Jr. Screening tools for depression in primary care: the effects of culture, gender, and somatic symptoms on the detection of depression. West J Med. 2001;175(5):349–52.

Azocar F, Arean P, Miranda J, Munoz RF. Differential item functioning in a Spanish translation of the Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(3):355–65.

Chang CM, Liao SC, Chiang HC, et al. Gender differences in healthcare service utilisation 1 year before suicide: national record linkage study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(5):459–60.

Chang TY, Liao SC, Chang CM, et al. Barriers to depression care among middle-aged and older adults in Taiwan’s universal healthcare system. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;26:100501.

Wu CS, Shau WY, Chan HY, Lai MS. Persistence of antidepressant treatment for depressive disorder in Taiwan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):279–85.

Hung CI. Factors predicting adherence to antidepressant treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(5):344–9.

Masand PS. Tolerability and adherence issues in antidepressant therapy. Clin Ther. 2003;25(8):2289–304.

Demyttenaere K, Donneau AF, Albert A, Ansseau M, Constant E, van Heeringen K. What is important in being cured from depression? Discordance between physicians and patients (1). J Affect Disord. 2015;174:390–6.

Demyttenaere K, Donneau AF, Albert A, Ansseau M, Constant E, van Heeringen K. What is important in being cured from: does discordance between physicians and patients matter? (2). J Affect Disord. 2015;174:372–7.

Hopwood M. The shared decision-making process in the pharmacological management of depression. Patient. 2020;13(1):23–30.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Servier provided funding for the CINP symposium and for the preparation of the supplement. This funding includes payment of the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Medical Writing and/ or Editorial Assistance

We would like to thank Catherine Rees and Karina Hamilton-Peel who provided editorial support with the development of the first and second drafts on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. This medical writing assistance was funded by Servier.

Authorship

Dr Chang meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has given his approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Dr Chang conceptualised the content of the presentation and article, developed the content for presentation, critically reviewed and revised all drafts of the article, and approved the article for submission.

Prior Presentation

This article and the accompanying articles in this supplement are based on presentations made by the authors at a Servier-funded virtual symposium titled “Anxiety Symptoms in Depression: Contemporary Treatment Approaches”, held in association with the 33rd International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) World Congress in June 2022, in Taipei, Taiwan.

Disclosures

Chia-Ming Chang has received research grants and/or consultancy honoraria from Servier, Lundbeck, and Janssen Pharma. This includes an honorarium from Servier for the presentation on which this publication is based.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The TAILOR survey received Institutional Review Board approval (IRB no. 202000335B0D001) and all patients provided informed consent.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, CM. What Do Patients Want in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder? Taiwan’s TAILOR Survey. Neurol Ther 12 (Suppl 1), 21–29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00471-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00471-y