Abstract

Introduction

Qualitative research on patient experiences in early-stage Parkinson’s disease (PD) is limited. It is increasingly acknowledged that clinical outcome assessments used in trials do not fully capture the range of symptoms/impacts that are meaningful to people with early-stage PD. We aimed to conceptualize the patient experience in early-stage PD and identify, from the patient perspective, those cardinal symptoms/impacts which might be more useful to measure in clinical trials.

Methods

In a mixed-methods analysis, 50 people with early-stage PD and nine relatives were interviewed. Study design and results interpretation were led by a multidisciplinary group of patient, clinical, regulatory, and outcome measurements experts, and patient organization representatives. Identification of the cardinal concepts was informed by the relative frequency of reported concepts combined with insights from patient experts and movement disorder specialists.

Results

A conceptual model of the patient experience of early-stage PD was developed. Concept elicitation generated 145 unique concepts mapped across motor and non-motor symptoms, function, and impacts. Bradykinesia/slowness (notably in the form of “functional slowness”), tremor, rigidity/stiffness, mobility (particularly fine motor dexterity and subtle gait abnormalities), fatigue, depression, sleep/dreams, and pain were identified as cardinal in early-stage PD. “Functional slowness” (related to discrete tasks involving the upper limbs, complex mobility tasks, and general activities) was deemed to be more relevant than “difficulty” to patients with early-stage PD, who report being slower at completing tasks rather than encountering significant impairment with task completion.

Conclusion

Patient experiences in early-stage PD are complex and wide-ranging, and the currently available patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments do not evaluate many early-stage PD concepts such as functional slowness, fine motor skills, and subtle gait abnormalities. The development of a new PRO instrument, created in conjunction with people with PD, that fully assesses symptoms and the experience of living with early-stage PD, is required.

Plain Language Summary

We conducted research to find out about the experiences and symptoms that have the greatest impact on everyday living for people with early-stage Parkinson’s disease. This research also looked at which symptoms patients think are important to be tracked in clinical trials. The research team running this study included people living with Parkinson’s disease (called “patient experts”). The team also included technical experts and representatives of patient organizations. To begin with, people living with early-stage Parkinson’s disease and relatives were interviewed. The interviews collected their thoughts on the impact of early-stage Parkinson’s disease on their daily lives. These insights revealed which experiences and symptoms were most important. The research team analyzed ideas and quotes from the interviews to create a picture of early-stage Parkinson’s disease. The symptoms that mattered the most to people living with early-stage Parkinson’s disease were tremor, rigidity/stiffness, fatigue, depression, sleep/dreams, and pain. Another important symptom was slowness of movement (which is called “bradykinesia/slowness”), and in particular “functional slowness,” which included tasks involving the upper limbs, complicated movement tasks, and general activities. Effects on mobility were also important, particularly fine motor skills and subtle walking abnormalities. This research shows the wide-ranging effects that early-stage Parkinson’s disease has on patients from their perspective. It also shows which effects are important to capture in trials of therapies aimed at this patient group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out the study? |

The clinical outcome assessments used in clinical trials investigating early-stage Parkinson’s disease do not fully capture the subtle concepts meaningful to people with this disease. |

Through interviews with people with early-stage Parkinson’s disease and their relatives, we aimed to conceptualize the patient experience and identify patient-recognized cardinal symptoms/impacts that may be more useful in clinical trials. |

What was learned from the study? |

The concepts identified as cardinal in early-stage Parkinson’s disease were bradykinesia/slowness (notably in the form of “functional slowness”), tremor, rigidity/stiffness, effects on mobility (particularly fine motor/dexterity and subtle gait abnormalities), fatigue, depression, sleep/dreams, and pain. |

A new patient-reported outcome instrument, developed with patients, is needed to accurately reflect the lived-experience of early-stage Parkinson’s disease. |

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive, incurable neurodegenerative disorder that leads to the loss of neurons at many sites [1, 2] both within the central nervous system and outside of it [1, 3], leading to a range of motor and non-motor features and disability [1]. There is currently no drug therapy available that can slow, stop, or reverse the progression of PD [1, 4]. The diagnosis of PD is traditionally based on motor features but people living with PD also have a range of non-motor symptoms, which often precede this diagnosis [3]. The condition progresses, leading to worsening motor abilities and gait abilities as well as a range of affective, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric problems [3], although the condition is somewhat heterogenous clinically [5].

Capturing the true problems of PD from the early stages is critical, as substantial research efforts are ongoing to find disease-modifying therapies and important and meaningful outcome measures for clinical trials [6]. Research specifically focused on the experience of people living with early-stage PD is limited and, to date, there is no consensus regarding the definition of early-stage PD among the scientific and regulatory communities. Early-stage disease has been defined by time (e.g., less than 5 years since diagnosis), functional impairment (i.e., Hoehn & Yahr [H&Y] stage I [mild, unilateral motor symptoms] and/or II [bilateral motor symptoms without balance impairment]), or a combination of both [e.g., at most 2 years since diagnosis and H&Y less than or equal to II]) [7,8,9,10]. The latter definition, coupled with the absence of symptomatic treatment, which has been referred to as “de novo PD,” is used mostly in the context of clinical trials targeted to people living with early-stage PD [11,12,13,14].

Legacy patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments typically used in PD research and clinical studies, such as the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) [15], and parts IB and II of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) [16], were not developed specifically for early-stage PD. Items of the MDS-UPDRS are not well targeted to early-stage PD [17] and conventional outcome measures such as the MDS-UPDRS do not capture the full range of symptoms or important aspects of clinical progression in PD that would be key assessments in a clinical trial [1].

A number of symptoms and functional impacts (motor and non-motor) are recognized in the clinical literature as relevant and specific to early-stage PD [3]. Furthermore, findings from surveys of people affected by PD, conducted by Parkinson’s UK and the Michael J. Fox Foundation (MJFF), demonstrate the relevance to patients of some of the well-established early-stage symptoms such as tremor, mobility, stiffness, slowness, and fine motor skills [18,19,20]. In addition, a survey of the most bothersome problems in PD [21] suggests consistent issues for patients across several disease stages but with differential importance. For example, tremor was the most frequently reported “bothersome” symptom by early-stage patients whereas postural instability and cognition were reported as being of the highest importance by late-stage patients [21].

More recently, a qualitative study has explored patient experiences in early-stage PD and presented a conceptual model of motor, non-motor, and impacts domains. This further suggests that legacy instruments, like the PDQ-39 and MDS-UPDRS, do not comprehensively capture all the subtle concepts relevant to early-stage PD, a stage where most disease-modifying therapies are being trialed [22].

Here we describe a novel, multidisciplinary, multi-stakeholder, patient-centered research partnership, with co-production of knowledge [23,24,25] at its center, that explored and conceptualized the experience of living with early-stage PD. This included identifying cardinal concepts related to symptoms and daily life impacts, which could be used as outcome measures in clinical trials.

Methods

This non-interventional study was based on an inductive, applied qualitative approach, not following specific epistemology, and used semi-structured interviews of people with early-stage PD and their relatives. Detailed line-by-line thematic analysis of the responses was used.

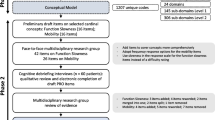

Both study design and interpretation of the findings were conducted by a multidisciplinary research group (Fig. 1) comprising six people living with PD (referred to as “patient experts” as these individuals are experts of their own disease [JA, GB, WB, PB, LG, CS]), representatives of patient organizations (Parkinson’s UK [NR] and Parkinson’s Foundation in the USA [CG, KS]), a regulatory science expert (AFS), clinical experts (i.e., trained neurologists in movement disorders [RAB, BB, and MB]), sponsor representatives (TM, KT), and experts in outcome measurements (StC, SoC). The panel of patient experts were identified in consultation with the patient organizations from their respective research support networks, to reflect diversity in gender, educational background, geographical location, time since diagnosis, and past involvement in clinical studies.

The study received ethics approval from the Copernicus Group Independent Review Board (protocol number 420180240) in the USA. As this was a non-interventional interview study with recruitment facilitated by patient associations and not the National Health Service (NHS), the UK Health Research Authority ethics committee indicated no NHS ethics approval was required. All participants were required to complete consent forms before proceeding to the interview. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration of 1964, and its later amendments.

Participants

Participants were recruited through Parkinson’s UK and the Parkinson’s Foundation (USA) and included people living with early-stage PD and relatives (spouses or partners). In the UK, a general email was sent to all members of the Parkinson’s UK Research Support Network (N = 6000) inviting them to take part in the study. After providing written informed consent, interested participants completed an electronic eligibility screening form. In the USA, the Parkinson’s Foundation circulated a targeted invitation to members of its Research Advocacy Program and Newly Diagnosed Initiative (where the former required participants to report the year they were diagnosed upon program entry, and the latter comprised people who had just received a diagnosis from a physician), aiming to primarily recruit people diagnosed within the past 2 years. Interested participants completed the consent form and electronic eligibility screening form.

For the purposes of this study, our recruitment targets were people with early-stage PD, distributed with a ratio of 4:1 between people with unilateral motor manifestations of PD (i.e., resting tremor or bradykinesia confined to one side of the body) and people with bilateral manifestations. To identify participants who met these inclusion criteria, and to facilitate the self-screening process, the eligibility screening form was developed in consultation with the clinical and patient experts, to describe the required early-stage PD signs and symptoms in layperson’s terms.

Interview Conduct

Identical semi-structured interview guides were used by the interviewers for both the patient and relative interviews, to ensure that all topics of interest were discussed. The objectives of the interviews were to (i) obtain insights about the course of early-stage PD and the impact on patients’ and relatives’ daily lives and (ii) identify which daily life domains are most impacted and which concepts are most important. Following an internal demonstration, interviews were conducted by five female research personnel from Modus Outcomes (DE [MSc], JM [BA], NM [PhD], RG [MSc], and SoC [PhD]), who introduced themselves, the interview goals, processes, and procedures, before starting the recording. During the 60–90 min telephone-based interviews (conducted between the participant and interviewer with no one else present), patients with early-stage PD and relatives were asked a series of open-ended questions about their disease experience. The open-ended nature of the questions aimed to elicit spontaneous responses. The interviewer noted each concept mentioned. In the event interviewees did not mention a concept of interest, the interviewer used prompts and probes to elicit responses related to these concepts (Table 1). Each participant was interviewed once; there were no repeat interviews.

Qualitative Analysis

Concept Elicitation

Interviews were recorded and the audio files were transcribed verbatim. Participants did not receive copies of the transcripts for comment/feedback. Transcripts were coded using ATLAS.ti software, and analyzed thematically [26] using detailed open line-by-line inductive coding [27, 28]. All themes were derived inductively on the basis of the interview data. Transcripts were coded by the team of five researchers from Modus Outcomes using a coding guide which outlined the principles and formatting framework of the open coding. The first two transcripts were coded by two researchers in parallel, and codes were reviewed and aligned within the research team before the remaining coding was completed. Researchers met regularly to discuss coding results and adjust coding style as needed.

A conceptual model of the patient experience in early-stage PD was developed following an iterative process using standard analytical techniques [28,29,30], where codes and necessary quotations were compared with the rest of the data, then inductively categorized into higher-order domains reflecting their underpinning conceptual content. The model comprised four levels of categories within which the codes were inductively categorized (subdomain level 2, subdomain level 1, domain, and overarching domain) (Fig. 2). Transcripts for the three participant groups (USA patients, UK patients, and relatives) were coded and analyzed in parallel to allow comparisons to be made. In line with the coding, the conceptual model categories were purposefully kept as detailed as possible, to allow for a granular assessment and comparison within and across the participant groups, countries, relatives, as well as between those with unilateral versus bilateral symptoms, and time since diagnosis (less than 2 years vs. more than 2 years).

Saturation Analysis

In qualitative studies, data saturation is widely used to calculate the required sample size [31,32,33,34]. In our study, we used conceptual saturation, which is defined, a priori, as the point at which no substantially new themes, descriptions of a concept, or terms are introduced as additional interviews are conducted [35]. However, there can be issues with assessing when data saturation is achieved and sample sizes can occasionally be very large, which can lead to inefficient use of time and resources [32,33,34]. As such, a smaller sample size can be considered adequate if the sample is homogenous and the aim of the study is narrow [33, 34]. In this study, conceptual saturation was assessed by ordering interviews chronologically, then placing interviews into six groups, allowing for a comparison of saturation within UK and US interviews. Concepts emerging in each group were compared sequentially to assess whether saturation had been reached at the subdomain-1 level. The first three groups comprised 10, 10, and 9 UK interviews, and the final three groups comprised 10, 10, and 10 US interviews. Saturation was achieved if no substantial new themes or unique concepts were elicited in the final three groups.

Identification of Cardinal Concepts for Early-Stage PD

Once the conceptual model of the patient experience in early-stage PD was established, three additional evidence sources were used to review the model output and to pinpoint cardinal concepts with relevance to early-stage PD. The three sources were:

-

The relative frequency of reported concepts within the interviewed participants with early-stage PD, comparing those with unilateral versus bilateral features and those who were less than 2 years vs. more than 2 years from diagnosis. Prespecified cutoff points were not used, and an exploratory assessment of relative frequency was performed using two levels of granularity, at the conceptual subdomain levels 1 and 2. Generally, counting is included in qualitative studies if it assists the emerging description and generates meaning from qualitative data [36]. In this instance, understanding the relative frequency of reported concepts among specific groups of patients highlights which of those concepts might be more relevant to a particular group.

-

Suggestions made by the six patient experts who critically reviewed the conceptual model, and indicated from their experience of the disease which were cardinal concepts for early-stage PD and potential markers of disease progression.

-

Feedback from nine USA-based movement disorder specialists, collected prior to study inception, informed the study’s wider objectives. These were (i) understanding symptomatology in early-stage PD and (ii) reviewing the adequacy of MDS-UPDRS part III in the context of use of early-stage PD (MDS-UPDRS parts Ib and II have already been shown to be of limited use in the context of early-stage PD) [37]. The consultation interviews were guided by discussion points (Table 1), audio recordings were made and the main findings were summarized.

Results

Sample

Fifty people living with early-stage PD participated in this study (interviews conducted June to December 2018): 25 via Parkinson’s UK and 25 via the Parkinson’s Foundation in the USA. Their characteristics are described in Table 2. A similar percentage of the participants self-reported unilateral PD symptoms in the UK and USA samples (80% vs. 76%, respectively). The median time since diagnosis was shorter in the USA sample compared with the UK sample (1 year vs. 2.5 years, respectively) owing to the different recruitment approach employed in the USA (Table 2). A total of nine relatives were recruited, who were either the spouse or partner of people living with early-stage PD, four in the UK and five in the USA (Table S1 in the supplementary material). None of the participants refused to participate or dropped out following consent.

Concept Elicitation

The early-stage PD experience was found to be wide-ranging and complex, with the 59 transcripts resulting in 1207 unique codes, relating to a total of 145 unique concepts. Codes were inductively categorized in a conceptual model of three overarching domains: motor symptoms/functions, non-motor symptoms/functions, and impacts related to early-stage PD (Fig. 2). Each of these three overarching domains comprised a three-tier categorization of the original codes (n = 1207), labeled as subdomains level 2 (n = 306), subdomains level 1 (n = 145), and domains (n = 24). Subdomains level 1 reflected unique concepts, whereas subdomains level 2 reflected further granularity and examples within these concepts.

A conceptual model for people living with early-stage PD was then refined and finalized on the basis of these domains (Fig. 3), with support from the patient experts, whose discussion and feedback led to the recategorization and streamlining of some concepts (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). The resultant model comprised three overarching domains and 24 domains (motor symptoms, n = 10; non-motor symptoms, n = 10; impacts, n = 4). Importantly, patient experts contributed by expanding, merging, or streamlining concepts generated from the codes. For example, the concept of “freezing” under the bradykinesia symptom domain was moved into the domains of activities affected by “freezing” (mobility, speech, cognitive).

Patient experience in early-stage PD. The figure displays an abbreviated presentation of the conceptual model for people living with early-stage PD based on overarching domains, domains, and subdomains level 1. Subdomains related to symptoms location, timeline, triggers, severity, or general subdomains (e.g., tremor general or fatigue general) are not presented on the figure. ADL activities of daily living, IADL instrumental activities of daily living, PD Parkinson’s disease

Domains Relating to Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms and Function, and Impact of Early-Stage PD

Results relating to motor and non-motor symptoms and function are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively, with subdomains presented in Tables S2 and S3 in the supplementary material, respectively.

The “motor symptoms/function” overarching domain comprises 10 domains (Fig. 3). Within this overarching domain, mobility was the most content-rich domain, as reflected by the number of level 1 subdomains and codes related to it. The mobility concept was much broader than gait alone: concepts included complex/whole body issues (bending, kneeling, general coordination, getting up/out of a seated/lying position, turning); gait/walking (including general issues, lifting/dragging legs/feet, smoothness of gait, shuffling, arm swing); lower limb function (issues related to standing); movement freezing (freezing feet, freezing while writing); and upper limb function (including carrying, lifting, holding, grip and power, fine motor/dexterity, handwriting). Similarly, the tremor domain was content-rich and supported by a vast number of participant and relative quotations. The concept of bradykinesia was well described by patients as a “functional” slowness across a range of simple tasks involving upper limb (e.g., brushing teeth), lower limb (e.g., walking), and more complex activities (e.g., cooking).

Like motor symptoms, the domains of “non-motor symptoms and function” varied in breadth of content. Of the nine non-motor symptom domains (excluding the non-specific/other domain), pain and bodily sensations contained the most subdomains and codes, and quotations were categorized to reflect general issues with pain as well as timeline and location. The sleep/dreams domain was also content rich, and concepts were grouped by the different aspects of sleeping problems which included difficulty falling asleep, insomnia, sleepiness, staying asleep, sleep quality, and sleep issues timeline. The neuropsychiatric domain (anxiety, depression, withdrawal, behavior change, hallucinations) differs from the psychological impacts domain under the impacts overarching domain, as the latter reflects day-to-day psychological aspects of living with early-stage PD. Furthermore, general problems with language and communication, distinct from motor speech and voice issues, were categorized within the domain cognitive functioning. Subdomains within cognitive functioning included attention/concentration, decision-making, disorganization, time lapse, difficulties with multitasking, difficulties with reasoning/problem solving, mental fog, and memory problems.

Results relating to the four impact domains, assessing psychological, interpersonal, practical/organizational, and activities impacted by early-stage PD, are reported in brief in Table 5 and more fully in Table S4 in the supplementary material. The psychological domain was the most content-rich impact subdomain. Quotations and codes related to the emotional toll of having early-stage PD were categorized in the mental health subdomain. Codes and quotations specific to avoiding people and/or situations due to early-stage PD and the impact of early-stage PD on the patient’s self-confidence were categorized into the confidence/nervousness/avoidance subdomains.

Concepts Mentioned by People with Early-Stage PD Versus Relatives

No country-specific differences were found between the unique concepts identified by UK and US participant transcripts. Outcomes from interviews with relatives provided some additional content for the conceptual model, mostly at a granular level within the motor and non-motor symptoms overarching domains. For example, concepts suggested by relatives alone included drooping head and leaning (posture domain) and vibrations whilst asleep (tremor domain) within the motor domains; decision-making and mental freezing/time lapse within the cognitive functioning domain, and behavioral changes within the neuropsychiatric domain.

Unilateral Versus Bilateral Manifestation and Disease Duration

Examination of the relative frequency of concepts most often reported by participants with unilateral (n = 39) versus bilateral manifestations (n = 11), as well as with a disease duration of less than 2 years (n = 37) vs. more than 2 years (n = 13) indicated that overall, the level 1 subdomain concepts were relevant to both groups. In other words, no level 1 subdomain concepts were found to be specifically unique to participants with unilateral manifestations and/or less than 2 years of disease duration. A closer more comparative view at the frequencies could indicate some concepts arose less frequently for participants with unilateral versus bilateral symptoms, e.g., rigidity (51% vs. 82%), speech/voice quality (51% vs. 73%), and saliva control (54% vs. 73%), as well as impact on basic (31% vs. 64%) and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL) (59% vs. 82%). Across all groups, tremor, upper limb issues, gait abnormalities, and fatigue were the four most frequently reported issues by participants (i.e., more than 69%). A snapshot of the most frequently reported concepts in early-stage patients (unilateral/0–2 years diagnosis) is presented in Fig. 3. A meaningful exploratory cutoff point of greater than 40% was selected to identify the more frequently reported concepts.

Identifying concepts characterizing both early-stage PD and progression of disease required a more granular review, achieved by examining the reporting patterns of level 2 subdomain concepts. This analysis identified clearer differences and trends in concept relevance across groups. For example, we compared concepts in the “upper limb” and “gait/walking” subdomains between participants with (a) unilateral manifestations and/or disease duration of less than 2 years and (b) bilateral manifestations and/or disease duration of more than 2 years. Fine motor/dexterity (71% vs. 23%) and arm swing issues (74% vs. 46%) were mentioned more frequently by those with early-stage disease, whereas issues related to carrying things (11% vs. 23%), stumbling (3% vs. 15%), or being unstable (0 vs. 8%) were mentioned more frequently by those with more advanced disease.

Saturation Analysis

Saturation analyses were conducted on unique concepts i.e., level 1 subdomains. Findings indicated that the concept elicitation results were comprehensive after the first 20 interviews, which produced the 24 domains presented in the model and 81% of the subdomains, adding granularity to the established domains of the conceptual model. The final three groups of interviews (30 in total conducted with US participants) did not introduce any new domains, but added granularity to them, with 15 new subdomains (concepts) being introduced. The final group of 10 interviews only added two new subdomain concepts to the model: “drooping head” and “double vision.” The saturation analysis findings therefore support the comprehensiveness of the concept elicitation analysis.

Identification of Cardinal Concepts for Early-Stage PD

The relative concept frequency review flagged several concepts across all three overarching domains as potentially of cardinal relevance to early-stage PD (Fig. 3), including, but not limited to, those suggested by previous patient surveys [18,19,20]. Similarly, the patient experts indicated concepts primarily within, but not limited to, motor domains, as well as suggesting some non-motor concepts and impacts as being of cardinal importance (Fig. 3). When reviewing general symptoms of early-stage PD, the nine movement disorder specialists discussed motor issues (including bradykinesia, dexterity, gait, stiffness, resting tremor, voice, and speech issues); non-motor issues (including fatigue, aches and pains, depression, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, and sense of smell) and impact issues (including feeling embarrassed). However, when addressing which concepts could be cardinal for outcome measurement in early-stage PD, they focused their suggestions on motor and just two non-motor concepts.

The synthesis of evidence from the three different sources shed light on conceptual domains of importance, which were then narrowed down further by the multidisciplinary research group on the basis of their potential to be used as appropriate outcomes in the context of early-stage PD clinical trials. Of these, consensus was reached on the cardinal importance of the tremor, rigidity/stiffness, bradykinesia/slowness (particularly “functional slowness”), and mobility (particularly upper limb and gait) concepts. “Functional slowness,” specifically, was voiced as being more relevant than “difficulty” in early-stage PD as patients start being slower at completing tasks but have not yet encountered significant impairment with task completion. Likewise, whilst decline in mobility is known as a feature of PD, agreement was reached that focusing specifically on more subtle gait abnormalities and problems with everyday mobility tasks was of particular importance to patients with early-stage PD.

All three sources of evidence identified non-motor symptoms and functions, fatigue, depression, sleep/dreams, and pain as being cardinal, whereas only the patient-centric sources indicated impact domains as being cardinal. Given the lack of an explicit link between disease, treatment, and other confounding variables that could contribute to more related concepts such as the psychological and professional activities impacts, the multidisciplinary research group decided against selecting any impact concepts as being potentially cardinal to measure, in the context of evaluating outcomes of a clinical trial from the patient perspective.

Discussion

The importance of incorporating patients’ experience with their condition in decision-making for healthcare and research is increasingly being recognized [38]. This is reflected in the commitment of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop guidance documents on how to collect and submit patient experience data and other relevant information from patients/caregivers to inform medical product development and regulatory decision-making [39,40,41]. In addition, progress is being made within the research community toward increased patient engagement, to better understand concepts that impact patients’ experiences with their disease [23]. This is particularly relevant to neurological disorders where many symptoms are not visible and can vary greatly throughout a 24-h period.

There is a growing recognition among the scientific and regulatory communities that existing outcome measures are limited in their capacity to evaluate outcomes in people with early-stage PD, notably to evaluate meaningful aspects of concepts of interest that are relevant to the patients’ ability to function in day-to-day life. For instance, recent qualitative studies exploring patient experiences in early-stage PD highlighted that legacy instruments like the PDQ-39 and MDS-UPDRS do not comprehensively capture all of the subtle concepts relevant to early-stage PD [22, 42]. Furthermore, Benz et al. reported a patient-centric approach to endpoint specification [43] and Regnault and colleagues recently advocated exploring alternatives to the MDS-UPDRS [17]. They suggested that research in partnership with patients with early-stage PD is critical to understand the course of early-stage PD and its impact; this study is in line with this recommendation. The multidisciplinary research team involved with the current study was a key strength and greatly facilitated the interpretation of results. This was particularly true regarding the identification of cardinal concepts in early-stage PD, where having the direct feedback of patient experts and clinicians in addition to the study participants was valuable. The rigorous scientific approach adopted here (by combining qualitative and quantitative methodologies) and the large sample size, which was in excess of that typically used in qualitative research, complied with FDA recommendations [41] and further assisted with the study objectives.

The current study greatly expands the body of knowledge about early-stage PD and crucially provides patient perspectives on symptoms/impacts of disease that are meaningful to them. Gathering this information directly from patients supports the development of more fit-for-purpose PROs that capture the concepts important to people with early-stage PD and could have the potential to more accurately demonstrate meaningful treatment benefit in clinical trials.

Our study demonstrated the broad range of concepts with potential for monitoring treatment benefit, including both motor and non-motor symptoms and functions as well as impacts of living with early-stage PD, reflecting the holistic and complex manifestations of early-stage PD. Cross-referencing evidence from three different sources identified the following as cardinal concepts in early-stage PD: bradykinesia/slowness (importantly slowness in function and activities), tremor, rigidity/stiffness, mobility (particularly fine motor dexterity and subtle gait abnormalities), fatigue, depression, sleep/dreams, and pain. Notably, the importance of the psychological and activities impacts of early-stage PD came from the study participants and patient experts, but were not specifically suggested or identified by the clinical experts or earlier surveys of people affected by PD [18,19,20], or the concepts indicated in the literature [3]. In the current study, saturation analysis in a homogenous population supports the comprehensiveness of the concept elicitation analysis; however, we acknowledge that more diverse interviews may have added further information.

A closer review of concepts such as bradykinesia/slowness, gait, and upper limb function, which are relevant across the stages of PD, flagged that in early-stage PD, subtle differences and concepts may be present that are not comprehensively captured by the broader PRO instruments currently in use. These include concepts related to “functional slowness” (including discrete tasks involving the upper limbs, complex mobility tasks, and general activities) and subtle gait abnormalities (including arm swing, or the “need” to concentrate on walking), and fine motor dexterity. In addition to the relative frequency, qualitative findings endorsed by the multidisciplinary research group further supported functional “slowness” as a concept potentially more relevant than “difficulty” in early-stage PD, where patients are starting to be slower at completing tasks but have not yet encountered significant difficulties.

One limitation of the current research is that it only recruited participants from the UK and USA and so the results may not be generalizable across the global Parkinson’s patient community. Another limitation was the lack of heterogeneity in the study population, with only White and non-Hispanic/non-Latino participants. A further limitation was the lack of access to participants’ medical records to cross-check clinical information and disease severity, as recruitment was based on self-report. However, we believe that our recruitment channels with our patient organization partners were appropriate and sound to ensure participants in this research met the criteria of having early-stage PD. These limitations are being addressed in other ongoing research efforts.

Our research builds on existing literature by providing more granular insights into the symptoms and burden experienced by people living with early-stage PD [21, 22, 44]. A similar patient-centered conceptual model in early-stage PD, finalized by clinical experts, was reported recently; this incorporated the patient perspective through quantitative social media listening analysis and qualitative patient concept elicitation interviews [22]. Our approach, however, placed patient experts at the center of the multidisciplinary team driving the study design, concept identification, and interpretation of results. Meaningful patient involvement in the design, execution, and analysis of this study is in line with the new patient-focused drug development paradigm which emphasizes the importance of involving patients in the entire life cycle of any therapy to ensure that research strategies address the unmet needs of patients [45,46,47].

Conclusion

This study successfully identified cardinal concepts in early-stage PD, which included “functional” slowness, fine motor dexterity, subtle gait abnormalities, fatigue, depression, sleep/dreams, and pain. The multidisciplinary research group assessed these in relation to their potential to be used as outcomes in clinical trials in the context of early-stage PD and concluded that bradykinesia/slowness (particularly functional slowness) and mobility (particularly upper limb and gait) would be the best measure to use in any such trials. The development of new PRO instruments, created in conjunction with patient research partners, geared toward assessing symptoms and experiences meaningful to people living with early-stage PD is required.

References

Evans JR, Barker R. Defining meaningful outcome measures in trials of disease-modifying therapies in Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12(8):1249–58.

Poewe W. Parkinson’s disease and the quest for preclinical diagnosis: an interview with Professor Werner Poewe. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2017;7(5):273–7.

Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17013.

Kieburtz K, Katz R, McGarry A, et al. A new approach to the development of disease-modifying therapies for PD; fighting another pandemic. Mov Disord. 2021;36(1):59–63.

Andrejack J, Mathur S. What people with Parkinson’s disease want. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(s1):S5–10.

Evans JR, Mason SL, Williams-Gray CH, et al. The natural history of treated Parkinson’s disease in an incident, community based cohort. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(10):1112–8.

Jankovic J, Rajput AH, McDermott MP, et al. The evolution of diagnosis in early Parkinson disease. Parkinson Study Group. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(3):369–72.

Goetz CG, Poewe W, Rascol O, et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2004;19(9):1020–8.

Simuni T, Siderowf A, Lasch S, et al. Longitudinal change of clinical and biological measures in early parkinson’s disease: Parkinson’s progression markers initiative cohort. Mov Disord. 2018;33(5):771–82.

Marek K, Jennings D, Lasch S, et al. The Parkinson progression marker initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95(4):629–35.

Hauser RA. Help cure Parkinson’s disease: please don’t waste the Golden Year. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018;4:29.

Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1268–78.

Schapira AH, McDermott MP, Barone P, et al. Pramipexole in patients with early Parkinson’s disease (PROUD): a randomised delayed-start trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):747–55.

Ren J, Hua P, Pan C, et al. Non-motor symptoms of the postural instability and gait difficulty subtype in de novo Parkinson’s disease patients: a cross-sectional study in a single center. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:2605–12.

Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):241–8.

Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23(15):2129–70.

Regnault A, Boroojerdi B, Meunier J, et al. Does the MDS-UPDRS provide the precision to assess progression in early Parkinson’s disease? Learnings from the Parkinson’s progression marker initiative cohort. J Neurol. 2019;266:1927–36.

Arbatti L, Nguyen A, McLauglin L, et al. Foundations for a patient-reported natural history of Parkinson disease: cross-sectional analysis of the MJFF Fox Insight (FI) platform. In: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; 21–27 April 2018; Los Angeles, CA.

Arbatti L, Nguyen A, McLauglin L, et al. Framework for a patient-reported natural history of Parkinson disease: motor and non-motor symptoms. In: 2nd Pan American Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Congress; 22–24 June 2018; Miami, FL.

Port RJ, Rumsby M, Brown G, et al. People with Parkinson’s disease: what symptoms do they most want to improve and how does this change with disease duration? J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(2):715–24.

Vinikoor-Imler L, Arbatti L, Hosamath A, et al. Cross-sectional profile of most bothersome problems as reported directly by individuals with Parkinson’s disease (2697). Neurology. 2021;97(16):795.

Staunton H, Kelly K, Newton L, et al. A patient-centered conceptual model of symptoms and their impact in early Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study. J Parkinsons Dis. 2022;12(1):137–51.

Hickey G, Brearley S, Coldham T, et al. Guidance on co-producing a research project. Southampton: INVOLVE. 2018. https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Copro_Guidance_Feb19.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Staniszewska S, Denegri S, Matthews R, et al. Reviewing progress in public involvement in NIHR research: developing and implementing a new vision for the future. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7): e017124.

Price A, Clarke M, Staniszewska S, et al. Patient and public involvement in research: a journey to co-production. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;105(4):1041–7.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–90.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–46.

Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2009.

Bryman A, Burgess B. Analyzing qualitative data. New York: Routledge; 2002.

Klassen A, Pusic A, Scott A, et al. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:11–8.

Lakens D. Sample size justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022;8(1):33267.

Morse JM. The Significance of Saturation. Qual Health Res. 1995;5(2):147–9.

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60.

Sebele-Mpofu F. Saturation controversy in qualitative research: complexities and underlying assumptions. A literature review. Cogent Soc Sci. 2020;6(1):1838706. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1838706.

Leidy NK, Vernon M. Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes: content validity and qualitative research in a changing clinical trial environment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(5):363–70.

Morse JM. Qualitative researchers don’t count. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(3):287.

Morel T, Cleanthous S, Andrejack J, et al., editors. Outcome assessment in early-stage Parkinson’s disease clinical trials: are legacy patient-reported outcome instruments fit for purpose? Poster presentation 570570. In: AAN virtual meeting; 2022.

Araujo R, Bloem BR. Listen to your patient: a fiddler’s tale. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(6):931–3.

Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development guidance public workshop: methods to identify what is important & select, develop or modify fit-for-purpose clinical outcomes assessments. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-methods-identify-what-important-patients-and-select. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: collecting comprehensive and representative input. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-collecting-comprehensive-and-representative-input. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: methods to identify what is important to patients. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-methods-identify-what-important-patients-guidance-industry-food-and. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Morel T, Cleanthous S, Andrejack J, et al. Outcome assessment in early-stage Parkinson’s disease (PD) clinical trials: are legacy patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments fit for purpose; Abstract 1570. In: Annual Meeting of the American Association of Neurology; 2–7 April 2022; Seattle, WA.

Benz HL, Caldwell B, Ruiz JP, et al. Patient-centered identification of meaningful regulatory endpoints for medical devices to treat Parkinson’s disease. MDM Policy Pract. 2021;6(1):23814683211021380.

Muller B, Assmus J, Herlofson K, et al. Importance of motor vs. non-motor symptoms for health-related quality of life in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(11):1027–32.

European Parliament, 2019–2024. A Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe: European Parliament resolution of 24 November 2021 on a pharmaceutical strategy for Europe (2021/2013(INI)). P9_TA(2021)0470. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0470_EN.html. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

ICH. Proposed ICH Guideline Work to Advance Patient Focused Drug Development. 2021. https://admin.ich.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/ICH_ReflectionPaper_PFDD_FinalRevisedPostConsultation_2021_0602.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Series for Enhancing the Incorporation of the Patient’s Voice in Medical Product Development and Regulatory Decision Making. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/fda-patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-series-enhancing-incorporation-patients-voice-medical. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Parkinson’s community for participating in this study to make this research possible. We thank Claire Nolan, previously Patient Engagement Lead at Parkinson’s UK, for her contribution to set up the early stages of this research. We acknowledge reference during research to the Fox Insight Study (FI), which is funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. We would also like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Milton Biagioni, of UCB Pharma, for his input into the later stages of this research and the thorough advice and review of this manuscript to ensure clinical meaningfulness, Irene de la Torre Arenas, of UCB Pharma, for her contribution to the development of the figures, and Jessica Mills, of Modus Outcomes, who facilitated the qualitative analysis. The authors would also like to thank Debi Ellis, Jessica Mills, Nadine McGale, and Rakhee Ghelani, of Modus Outcomes, for conducting the interviews alongside Sophie Cleanthous. Roger A. Barker is supported through the NIHR-funded Cambridge Biomedical Research Center.

Funding

Funding for the study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was provided by UCB Pharma, Brussels, Belgium.

Medical Writing Assistance

The authors acknowledge Tamara Bailey, PhD, CMPP, and Luke Edmonds, MSc, of Ashfield MedComms, an Ashfield Health company, for editorial support that was funded by UCB Pharma in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception/design, material preparation/data collection/analysis, writing of the manuscript, review, and approval of the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Stefan Cano and Sophie Cleanthous are employees of Modus Outcomes that provided research and analysis services to UCB Pharma. Babak Boroojerdi, Kate Trenam, and Thomas Morel are employees and shareholders of UCB Pharma. Casey Gallagher and Karlin Schroeder (Parkinson’s Foundation) and Natasha Ratcliffe (Parkinson’s UK) are staff experts in patient engagement/involvement in research; since the completion of the study, Natasha Ratcliffe has changed her affiliation from Parkinson’s UK, London, UK to COUCH Health, Manchester, UK. Geraldine Blavat, John Andrejack, and William Brooks (Parkinson’s Foundation), and Carroll Siu, Lesley Gosden, and Paul Burns (Parkinson’s UK) are patient experts. Ashley F. Slagle is an employee of Aspen Consulting, LLC that provides consulting services to UCB Pharma. Ashley F. Slagle reports personal fees from UCB Pharma outside of the submitted work. Casey Gallagher, Carroll Siu, Geraldine Blavat, John Andrejack, Karlin Schroeder, Lesley Gosden, Natasha Ratcliffe, Paul Burns, Roger A. Barker, and William Brooks have no potential conflicts of interest to report.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study received ethics approval from the Copernicus Group Independent Review Board (protocol number 420180240) in the USA. As this was a non-interventional interview study with recruitment facilitated by patient associations and not the National Health Service (NHS), the UK Health Research Authority ethics committee indicated no NHS ethics approval was required. All participants were required to complete consent forms before proceeding to the interview. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration of 1964, and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as data from non-interventional studies are outside of UCB’s data sharing policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morel, T., Cleanthous, S., Andrejack, J. et al. Patient Experience in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease: Using a Mixed Methods Analysis to Identify Which Concepts Are Cardinal for Clinical Trial Outcome Assessment. Neurol Ther 11, 1319–1340 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00375-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00375-3