Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to investigate clinical outcomes in young patients with basilar artery occlusion (BAO) receiving endovascular therapy (EVT).

Methods

Consecutive patients with BAO within 24 h who underwent EVT from the BASILAR Registry study were enrolled. We compared clinical outcomes of young patients (aged 18–55 years) with older patients (aged > 55 years) with stroke due to BAO at 90 days and 1 year after EVT. The primary and secondary outcomes were improvement in modified Rankin scale scores (mRS) at 90 days and either favorable (mRS 0–3) or mortality at 90 days, respectively.

Results

A total of 646 patients were included, of which 152 (23.53%) were aged 18–55 years. Dyslipidemia (42.11% vs. 30.36%, p = 0.007) and good collateral circulation (60.52% vs. 46.35%, p = 0.002) were more frequent in young patients than older. Stroke etiologies in young patients included large artery atherosclerosis (67.11%), cardioembolism (15.13%), and vessel dissection (5.26%). Young patients were associated with better prognosis (mRS: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.21–2.48; mRS 0–3: aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.01–2.54; mortality: aOR 0.60; 95% CI 0.38–0.93) at 90 days. Baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (pc-ASPECTS), and sex were independent predictors of clinical outcomes of young patients at 90 days after EVT.

Conclusion

Young patients with BAO had better clinical outcomes after EVT than old patients. Predictors of clinical outcomes in young patients undergoing EVT included baseline NIHSS score, pc-ASPECTS, and sex.

Trial Registration

Clinical Trial Registration-URL: ChiCTR180001475 (www.chictr.org.cn).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Among young patients, acute ischemic stroke due to basilar artery occlusion is uncommon and associated with high rates of functional dependency |

In this cohort study of 646 patients with acute basilar artery occlusion, young patients were associated with increased odds of improvement in modified Rankin scale scores at 90 days and 1 year compared with old patients after endovascular therapy |

This multicenter clinical study indicates that young patients receiving endovascular therapy had a better clinical prognosis than old patients. Further studies are warranted to explore the optimal therapy in young patients with acute basilar artery occlusion |

Introduction

Basilar artery occlusion (BAO) accounts for 1% of ischemic strokes and 10% of large artery occlusions and is associated with high morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Pooled analysis has demonstrated the benefit of endovascular therapy (EVT) for patients with acute BAO [3, 4]. Although the recent randomized trials failed to verify the superiority of EVT over standard medical therapy in patients with acute BAO, a substantial benefit of EVT could not be excluded because of inherent limitations of the two trials, such as high crossover rate [5] and poor recruitment [6].

The incidence of stroke in young patients comprises 15–20% of the total, corresponding to about 30,000 strokes in young adults per year [7]. Young patients (aged < 50 years) with stroke accounted for up to 19% in the BASICS registry study [8] and up to 11.3% in the BASICS trial [6] of all acute BAO. Large vessel occlusion in young patients is often accompanied by fewer vascular risk factors and inapparent pathological changes in vascular structures, including fewer tortuous vessels, atherosclerosis, and calcification [9,10,11,12]. Thus, the causes of vessel occlusion and responses to EVT in young patients are different from those of elderly patients. Growing evidence indicates that young patients could get more benefit from EVT than older ones [13, 14]. However, specific investigations in young patients with acute BAO treated with EVT are rare. In young patients with acute BAO, the performance characteristics and clinical outcomes after EVT, as well as the related prognostic factors, are still largely uncertain.

Therefore, our study aimed to elucidate the clinical outcomes of young patients with acute BAO who underwent EVT, and identify the factors influencing the prognosis after EVT in young patients.

Methods

Patient Population

We analyzed data from the Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion (BASILAR) study, a multicenter registry study which included patients from 47 comprehensive stroke centers running in China from January 2014 to May 2019. All patients were over 18 years old and diagnosed with acute BAO via computed tomography angiography, digital subtraction angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography. The local neurologist and neuroradiologist evaluated the exact therapy modalities and endovascular procedures including stent retrievers and/or aspiration, balloon angioplasty, stenting, intra-arterial thrombolysis, or combinations of these approaches within 24 h, according to the standard-of-care recommendation and clinical experience. Patients were excluded because of significant preexisting disability (modified Rankin scale [mRS] > 2), cerebral hemorrhage, missing follow-up information at 90 days, pregnancy, and terminal illness [4]. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Xinqiao Hospital (Second Affiliated Hospital), Army Medical University (No. 201308701), and the local ethics committee of each site. Informed consent was acquired from each patient and/or their legal surrogates according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Once the written consent was obtained, the investigators could access the corresponding secondary information related to the initial morbidity with permission.

Data Collection

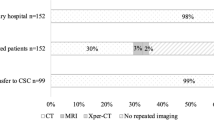

The laboratory results of all patients were collected by the study neurologists. In addition, the medical history provided by the patients or their family members was obtained from their previous records. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) reflected the neurologic deficit on admission [15]. Furthermore, all imaging data were assessed in a centralized manner by two neuroradiologists, who did not know any clinical information except for the lesion side. The posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (pc-ASPECTS), which is a well-established reference, was used to examine the infarction degree of posterior circulation ischemic stroke [16]. The collateral status of posterior circulation was estimated on the basis of the Posterior Circulation Collateral Score (PC-CS) [17]. The site of occlusion was usually divided into four segments for basilar artery (VA-V4, proximal, middle, and distal), and the etiology of stroke was classified as one of four types (large artery atherosclerosis (LAA), cardioembolism (CE), other, and unknown) according to Trial of ORG10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). The onset of symptoms was registered according to the description of the patient or a witness.

Outcome Assessment

To evaluate the improvement in neurological functions, the mRS was rated in a blind manner at two follow-ups of 90 days and 1 year after EVT, either via telephonic interviews with the patients and their families or during the hospital visit. The efficacy outcomes were defined as good (mRS 0–2), favorable (mRS 0–3), unfavorable (mRS 4–6), or death (mRS 6). In addition, the safety outcome was registered as symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) within 48 h after EVT. Intracerebral hemorrhages were evaluated on the basis of the Heidelberg Bleeding Classification [18]. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was considered as either an increase of at least 4 points of NIHSS, an increase of at least 2 points in one NIHSS category, or requiring additional surgery because of clinical deterioration (hemicraniectomy and external ventricular drain placement). Other outcomes included successful recanalization (modified therapy in cerebral infarction [mTICI] score of 2b to 3) and first-pass [19] (one pass, mTICI score of 2c to 3), where there was no requirement for rescue therapy with adjunctive using of balloon angioplasty, stenting, or intra-arterial infusion of drugs achieving recanalization.

Statistical Analysis

The continuous variables were described using median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and the difference between the two groups was compared using Kruskal–Wallis/Mann–Whitney U test. The categorical variables were presented using percentages and either Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test was applied to examine the differences. In order to evaluate the cumulative probability of survival during a 1-year follow-up period, the Kaplan–Meier method was performed. The intergroup difference (age > 55 years vs. age 18–55 years) was explored using the log-rank test.

We assessed the association of different clinical outcomes (favorable outcome, mortality, first pass, mTICI 2b–3, sICH) in young patients at 90 days and 1-year after EVT with hyperlipidemia, smoking, baseline NIHSS score, baseline ASPECTS, PC-CS, and diastolic blood pressure by performing multivariable logistic regression adjusted for those variables. Furthermore, we evaluated the predictors of clinical outcomes (favorable outcome and mortality) of these patients at 90 days after EVT, selected by univariate analysis with p < 0.05 (eTable 1 in the supplementary material) and reported in the literature. Besides, the predictors of favorable outcome and mortality were assessed during 1-year follow-up.

The missing baseline data of our study was not imputed. Sensitivity analysis was performed to analyze the association of young with their clinical outcomes using the multiple imputation method (eTable 2 and eFig. 1 in the supplementary material) owing to partial loss of follow-up at 1 year. No significant changes were observed between with and without imputation conditions. All statistical analyses were calculated using SPSS statistical software version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Percentage bar plots were represented using Excel 2020 software (Microsoft). The Kaplan–Meier survival plot was drawn using RStudio software (version 1.3.1093). In all reported studies, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two sides).

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Young Versus Old Patients

From the prospective BASILAR registry, 646 patients who underwent EVT at symptom onset within 24 h were included in our subgroup analysis (Fig. 1). The median age was 64 (IQR 56–73) years, 163 patients (25.23%) were female, and 152 patients (23.52%) were aged 18–55 years. Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1. In young patients, median (IQR) baseline NIHSS and baseline pc-ASPECTS were 27 (IQR 16–32) and 8 (IQR 7–10), respectively. Young patients had high diastolic blood pressure (86.50 vs. 84.00, p = 0.04) and often history of dyslipidemia (42.11% vs. 30.36%, p = 0.007) and smoking (46.05% vs. 33.40%, p = 0.005). Besides, good collateral circulation was observed in young patients (PC-CS over 5 scores: 60.52% vs. 46.35%, p = 0.002). Hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and cardioembolic were more frequent in old patients. Stroke etiologies in young patients included large artery atherosclerosis (LAA, 67.11%), cardioembolism (CE, 15.13%), and vessel dissection (5.26%) (eTable 3 in the supplementary material).

Clinical Outcomes in Young Versus Old Patients

The outcomes at the 90-day follow up after EVT are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2a. Young patients had more frequently favorable outcomes (40.78% vs. 29.35%, p = 0.008) and good outcomes (37.50% vs. 24.299%, p = 0.001) than old patients. In ordinal shift analysis, after adjustment for confounders, we found an association between young patients and functional outcomes (adjusted common odds ratio [acOR] 1.73; 95% CI [1.21–2.48]). The associations between young patients and favorable outcomes were confirmed by multivariable logistic regression analysis (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.01–2.54). Among a total of 299 patients, the frequency of mortality was higher in old patients (48.99% vs. 37.50%, p = 0.01), whereas the occurrence of sICH was not significantly different between young and old patients (6.57% vs. 7.18%, p = 0.80). Concerning the 1-year follow-up, young patients with stroke had a greater chance of achieving favorable outcomes (47.34% vs. 32.38%, p = 0.001) than old patients. Mortality within 1 year was 54.90% for old patients compared to 43.40% for young (p < 0.05, Table 2, Figs. 2b and 3). The sensitivity analysis showed that young patients with stroke had a better prognosis at 1 year (eTable 2 and eFig. 1 in the supplementary material), which was equivalent to the data presented before using the multiple imputation method.

Predictors of Favorable Outcome and Mortality in Young Patients at 90 Days

Table 3 shows the predictors for the two outcome categories (favorable outcome and mortality at 90 days). In a multivariable logistic regression model, the following variables were independently predictive of a favorable outcome: baseline NIHSS score (aOR 0.92; 95% CI 0.88–0.97, p < 0.001), baseline pc-ASPECTS (aOR 1.73; 95% CI 1.25–2.40, p = 0.001), and successful recanalization (aOR 2.20; 95% CI 1.51–3.20, p < 0.001). Mortality was associated with sex (aOR 3.08; 95% CI 1.03–9.25, p = 0.045) and baseline NIHSS (aOR 1.12; 95% CI 1.06–1.18, p < 0.001). The predictors of clinical outcomes at 1 year are presented in eTable 4 in the supplementary material.

Discussion

Our study provided evidence of a better prognosis in young patients with acute BAO. Besides, baseline NIHSS, baseline pc-ASPECTS, and sex were independently associated with clinical outcomes in young EVT cohorts. Furthermore, we revealed young patients with BAO due to dissection.

The appropriate age definition of “young” patients with stroke is unclear. In the literature, age ranges of 18–40 [20], 18–49 [10], or 18–55 [21] years have been given for young patients with stroke. Fifty-five years is the cutoff age in some studies [21,22,23] with appropriate sample sizes, taking into consideration the fact that individuals younger than 55 years of age usually remain healthy because of improving medical conditions. In the BASILAR registry, the occurrence of young patients (aged 18–55 years) with stroke was 23.5% of the whole EVT cohort. The frequency of young patients (aged < 50 years) with stroke was approximately 19% in the BASICS registry study [8] and 11.3% in the BASICS trial [6] of all acute BAO. Our study found that young patients with stroke had a good arterial collateral network (PC-CS > 5 scores, 60.52% vs. 46.35%, p = 0.002). A possible explanation was that cardiovascular risk factors may impede angiogenesis during the pruning of collaterals [14]. Thus, chronic exposure to cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking could impair endothelial function and stiffen the vessels’ myogenic tone leading to a decline in artery diameter [24, 25]. Two subgroup analyses of MR CLEAN also noted that young patients with stroke had higher collateral circulation grade scores (grade 3, 27.60% vs. 18.50%, p < 0.001 [10]; median age, grade 1 vs. grade 3 = 72 years vs. 67 years, p < 0.001 [14]). Besides, 5.26% of young patients showed vessel dissection, which is an etiological factor for stroke due to BAO. Dissections involving the basilar artery have been reported much less frequently. The Helsinki Young patients with stroke Registry showed that 2 of 426 patients (4.69%) had basilar artery dissection and 68 of 532 patients (12.78%) had internal carotid dissection [26]. Chang et al. [27] also observed that 6.9% of young patients had vessel dissection in patients with posterior circulation ischemic stroke. Indeed, we found that the occurrence of vessel dissection was 11.40% in patients aged less than 50 years with acute BAO.

Young patients were associated with better clinical outcomes, which was consistent with existing literature [10, 11, 28, 29]. For example, 40.78% (62/152) of young patients with stroke achieved favorable outcomes at 90 days, resulting in a difference of 11.43% (95% CI 2.65–20.22) compared with old patients. Besides, mortality within 90 days was less frequent in young patients (37.50% vs. 48.99%, p = 0.013) with an absolute difference of 11.49% (95% CI 2.62–20.36). At 1-year follow up, the Kaplan–Meier survival plot (Fig. 3) also indicated that young adults had a better prognosis. In a real-world multicenter experience, 66.20% of young patients (aged < 50 years) who underwent EVT because of large artery occlusion achieved favorable outcomes and 4.70% of the patients died [11]. For these patients, the rate of favorable clinical outcome (mRS 0–2) at 3 months was higher (61.00% vs. 38.80%) and mortality was lower (6.80% vs. 31.90%) than in old patients according to the MR CLEAN Registry [10]. One possible explanation could be that young patients with stroke are in general healthier individuals with more compensatory capabilities and less comorbidity. Another explanation could be that young patients have a lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and thus they a higher probability of achieving complete rehabilitation than old patients. Supporting this idea, young patients were found to have good artery collateral circulation, which has been associated with a favorable outcome and low mortality.

Our findings also reveal associations between admission NIHSS, pc-ASPECTS, and recanalization and favorable outcomes at 90 days, which is further supported by previous studies [30, 31]. Interestingly, we found sex as an independent predictor of mortality within 90 days for young patients. Indeed, young women have a lower probability of mortality within 90 days (19.35% vs. 42.15%, p = 0.02) and less cardiovascular risk (hypertension (38.71% vs. 64.46%, p = 0.009) and dyslipidemia (25.81% vs. 46.28%, p = 0.04) compared with men (eTable 5 in the supplementary material). This is in contradiction with the findings of previous studies that showed sex was independently associated with clinical prognosis. Eriksson et al. revealed that the association between sex and clinical outcome was not significant for patients with ischemic stroke [32]. Chalos et al. [33] also demonstrated that sex could not predict mortality within 90 days in patients who underwent EVT. Among patients with BAO, Tan et al. [34] indicated that the functional outcomes were comparable between men and women. One cause of the discrepancy between ours and the aforementioned studies may be the included population. While these studies aim to analyze the differences in sex based on the whole population, our study analyzes young patients with stroke only. Estrogen is considered a protective factor against ischemic stroke in young women because of its neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties [35]. Consistently, the risk of stroke more rapidly increases in postmenopausal women, in whom estrogen levels are lower. Up to 35.80% of women with ischemic stroke, a staggering number of 100,000, are aged 60–69 years, while 19.67% are aged 50–59 years [36]. Meanwhile, good collateral circulation is associated with low mortality. Pooled data from 1764 participants in the seven randomized controlled trials on EVT within the HERMES collaboration showed that women have higher collateral grades (grade 3, 46% vs. 35%; p < 0.001) than men [33]. MR CLEAN subgroup analysis reported that women have good collateral circulation (grade 3, 53% vs. 47%) [14]. Our findings also showed that young female cohorts have high collateral grades (64.52% vs. 59.50%), but the difference between men and women was insignificant. In addition, lower rates of bridge intravenous thrombolysis (19.07% vs. 39.40%), hypertension (59.21% vs. 76.20%), and diabetes (19.07% vs. 28.8%), and shorter onset to puncture time (330 vs. 359.60 mins) were found in young patient in our study compared with a multicenter cohort study [34]. The findings of Guenego et al. supported our results as sex was a predictor of mortality in patients with BAO treated with EVT [37]. However, the mortality within 1 year is comparable between men and women (eTable 5 in the supplementary material). The Kaplan–Meier curve of young patients with stroke (eFig. 2 in the supplementary material) revealed that mortality increases more rapidly at 9 months in women than in men. Stroke unit care may improve neurological recovery [38]. However, female patients were less likely to be admitted directly to the stroke unit, hence missing the opportunity to achieve functional independence compared with male patients [32]. In stroke management, women are less likely to receive therapeutic statins or anticoagulation [39], which may increase the risk of stroke. We hypothesize that women may have high rates of stroke recurrence. In fact, we found a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation (22.58% vs. 5.79%, p = 0.01) and cardioembolism (25.81% vs. 12.40%, p = 0.001), which are considered predictors of stroke recurrence, in women compared with men. Besides, a meta-analysis showed that 3.1% of patients had stroke recurrence at 90 days and 11.1% at 1 year [40]. Regrettably, information on stroke recurrence was not available from the BASILAR Registry and thus we were unable to identify the stroke recurrence in women at 30 days and 1 year after EVT.

One of the strengths of this study is its elucidation of the characteristics of BAO in young adults. In addition, the effect of EVT also was investigated in young and old patients with stroke due to acute BAO. Nevertheless, our study has some limitations. As a retrospective national registry, it was a non-randomized study, which confers an inherent risk of bias and an inability to determine causality. We could only determine the etiology of stroke in young patients with BAO. The difference between young and old patients was not entirely identified. The unequal number of young and old cohorts found in our study was due to stroke being a common disease of old age. Considering the age strata difference, multivariable analyses were used to adjust the unequal clinical outcomes. Additionally, the sample size of the young patients was moderate. Further large prospective studies are warranted to further investigate this relationship.

Conclusions

In our study, young patients with ischemic stroke due to BAO had a higher chance of achieving functional independence and had lower mortality after undergoing EVT than old patients. Predictors of clinical outcomes in young patients included baseline NIHSS score, pc-ASPECTS, and sex. Future clinical trials and cooperative analysis of larger sample sizes of young patients with BAO are needed to extract robust conclusions about these associations.

Change history

05 August 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00391-3

References

Greving JP, Schonewille WJ, Wijman CAC, Michel P, Kappelle LJ, Algra A. Predicting outcome after acute basilar artery occlusion based on admission characteristics. Neurology. 2012;78(14):1058–63.

Wu L, Zhang D, Chen J, et al. Long-term outcome of endovascular therapy for acute basilar artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(6):1210–8.

Pirson FAV, Boodt N, Brouwer J, et al. Endovascular treatment for posterior circulation stroke in routine clinical practice: results of the multicenter randomized clinical trial of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke in the Netherlands registry. Stroke. 2022;53(3):758–68.

Zi W, Qiu Z, Wu D, et al. Assessment of endovascular treatment for acute basilar artery occlusion via a nationwide prospective registry. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):561–73.

Liu X, Dai Q, Ye R, et al. Endovascular treatment versus standard medical treatment for vertebrobasilar artery occlusion (BEST): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):115–22.

Langezaal LCM, van der Hoeven EJRJ, Mont’Alverne FJA, et al. endovascular therapy for stroke due to basilar-artery occlusion. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1910–20.

George MG. Risk factors for ischemic stroke in younger adults: a focused update. Stroke. 2020;51(3):729–35.

Schonewille WJ, Wijman CAC, Michel P, et al. Treatment and outcomes of acute basilar artery occlusion in the Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): a prospective registry study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(8):724–30.

van Alebeek ME, Arntz RM, Ekker MS, et al. Risk factors and mechanisms of stroke in young adults: the FUTURE study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38(9):1631–41.

Brouwer J, Smaal JA, Emmer BJ, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy in young patients with stroke: a MR CLEAN registry study. Stroke. 2022;53(1):34–42.

Yeo LL-L, Chen VHE, Leow AS-T, et al. Outcomes in young adults with acute ischemic stroke undergoing endovascular thrombectomy: a real-world multicenter experience. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(8):2736–44.

Yesilot Barlas N, Putaala J, Waje-Andreassen U, et al. Etiology of first-ever ischaemic stroke in European young adults: the 15 cities young stroke study. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(11):1431–9.

Maaijwee NAMM, Rutten-Jacobs LCA, Schaapsmeerders P, van Dijk EJ, de Leeuw F-E. Ischaemic stroke in young adults: risk factors and long-term consequences. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(6):315–25.

Wiegers EJA, Mulder MJHL, Jansen IGH, et al. Clinical and imaging determinants of collateral status in patients with acute ischemic stroke in MR CLEAN trial and registry. Stroke. 2020;51(5):1493–502.

Kwah LK, Diong J. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). J Physiother. 2014;60(1):61.

Khatibi K, Nour M, Tateshima S, et al. Posterior circulation thrombectomy-pc-ASPECT score applied to preintervention magnetic resonance imaging can accurately predict functional outcome. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:e566–71.

van der Hoeven EJ, McVerry F, Vos JA, et al. Collateral flow predicts outcome after basilar artery occlusion: the posterior circulation collateral score. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(7):768–75.

von Kummer R, Broderick JP, Campbell BCV, et al. The Heidelberg bleeding classification: classification of bleeding events after ischemic stroke and reperfusion therapy. Stroke. 2015;46(10):2981–6.

Aubertin M, Weisenburger-Lile D, Gory B, et al. First-pass effect in basilar artery occlusions: insights from the endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke registry. Stroke. 2021;52(12):3777–85.

Dodds JA, Xian Y, Sheng S, et al. Thrombolysis in young adults with stroke: findings from get with the guidelines-stroke. Neurology. 2019;92(24):e2784–92.

Schöberl F, Ringleb PA, Wakili R, Poli S, Wollenweber FA, Kellert L. Juvenile stroke. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(31–32):527–34.

Nakagawa K, Ito CS, King SL. Ethnic comparison of clinical characteristics and ischemic stroke subtypes among young adult patients with stroke in Hawaii. Stroke. 2017;48(1):24–9.

Boot E, Ekker MS, Putaala J, Kittner S, De Leeuw F-E, Tuladhar AM. Ischaemic stroke in young adults: a global perspective. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(4):411–7.

Schirmer SH, van Nooijen FC, Piek JJ, van Royen N. Stimulation of collateral artery growth: travelling further down the road to clinical application. Heart. 2009;95(3):191–7.

Zeiher AM, Drexler H, Saurbier B, Just H. Endothelium-mediated coronary blood flow modulation in humans. Effects of age, atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(2):652–62.

Putaala J, Metso AJ, Metso TM, et al. Analysis of 1008 consecutive patients aged 15 to 49 with first-ever ischemic stroke: the Helsinki young stroke registry. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1195–203.

Chang F-C, Yong C-S, Huang H-C, et al. Posterior circulation ischemic stroke caused by arterial dissection: characteristics and predictors of poor outcomes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;40(3–4):144–50.

Arsava EM, Vural A, Akpinar E, et al. The detrimental effect of aging on leptomeningeal collaterals in ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(3):421–6.

Groot AE, Treurniet KM, Jansen IGH, et al. Endovascular treatment in older adults with acute ischemic stroke in the MR CLEAN Registry. Neurology. 2020;95(2):e131–9.

Novakovic-White R, Corona JM, White JA. Posterior circulation ischemia in the endovascular era. Neurology. 2021;97(20 Suppl 2):S158–69.

Alemseged F, Rocco A, Arba F, et al. Posterior National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale improves prognostic accuracy in posterior circulation stroke. Stroke. 2022;53(4):1247–55.

Eriksson M, Åsberg S, Sunnerhagen KS, von Euler M. Sex differences in stroke care and outcome 2005–2018: observations from the Swedish stroke register. Stroke. 2021;52(10):3233–42.

Chalos V, de Ridder IR, Lingsma HF, et al. Does sex modify the effect of endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke? Stroke. 2019;50(9):2413–9.

Tan BYQ, Siow I, Lee KS, et al. Effect of sex on outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy in basilar artery occlusion: a multicentre cohort study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;1–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000524048.

Koellhoffer EC, McCullough LD. The effects of estrogen in ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4(4):390–401.

Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation. 2017;135(8):759–71.

Guenego A, Lucas L, Gory B, et al. Thrombectomy for comatose patients with basilar artery occlusion: a multicenter study. Clin Neuroradiol. 2021;31(4):1131–40.

Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(9):CD000197.

Andrade JG, Deyell MW, Lee AYK, Macle L. Sex differences in atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(4):429–36.

Mohan KM, Wolfe CDA, Rudd AG, Heuschmann PU, Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Grieve AP. Risk and cumulative risk of stroke recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1489–94.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the co-investigators of BASILAR for their dedication to the study.

Funding

The fee for printing and copying the medical records was provided by multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing intracranial angioplasty and/or stenting with aggressive drug therapy for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (No. 2018C004). The fee of statistical consultation was supported by Application of intravenous thrombolysis with Tenecteplase and bridging endovascular therapy in acute large vessel occlusion (No. 2021JSLC0001). The professional service fees was provided by Army Medical University Clinical Medical Research Talent Training Program (No. 2018XLC1005); Fuling District Science and Technology Project (No. FLKJ,2021ABB1019). The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the corresponding authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Jinrong Hu, Xing Liu, and Shuai Liu analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; Hongfei Sang and Jiacheng Huang supervised the design and execution of the study and contributed to subsequent versions of the manuscript; Weidong Luo, Jie Wang, Zhuo Chen, Shuang Yang, Wencheng He, Bo Zhang, Zhou Yu, Shan Wang, Hongbin Wen, Xiurong Zhu, Ruidi Sun, Jie Yang, Linyu Li, Jiaxing Song, Yan Tian, Zhongming Qiu, Fengli Li, and Wenjie Zi help us with the statistical analyses; Yaoyu Tian and De Yang had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors reviewed the study report, made comments or suggestions on the manuscript drafts, and approved the final version.

Disclosures

Jinrong Hu, Xing Liu, Shuai Liu, Hongfei Sang, Jiacheng Huang, Weidong Luo, Jie Wang, Zhuo Chen, Shuang Yang, Wencheng He, Bo Zhang, Zhou Yu, Shan Wang, Hongbin Wen, Xiurong Zhu, Ruidi Sun, Jie Yang, Linyu Li, Jiaxing Song, Yan Tian, Zhongming Qiu, Fengli Li, Wenjie Zi, Yaoyu Tian and De Yang have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Xinqiao Hospital (Second Affiliated Hospital), Army Medical University, (No. 201308701), and the local ethics committee of each site. Informed consent was acquired from each patient and/or their legal surrogates according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Once the written consent was obtained, the investigators could access the corresponding secondary information related to the initial morbidity with permission.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised to correct the affiliation of author De Yang and to include a funding detail.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Liu, X., Liu, S. et al. Outcomes of Endovascular Therapy in Young Patients with Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion: A Substudy of BASILAR Registry Study. Neurol Ther 11, 1519–1532 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00372-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00372-6