Abstract

Introduction

A greater understanding of the reality of living with myasthenia gravis (MG) may improve management and outcomes for patients. However, there is little published data on the patient perspective of how MG impacts life. Our objective was to reveal the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective.

Methods

This analysis was led by an international Patient Council comprising nine individuals living with MG who serve as local/national patient advocates in seven countries (Europe and the United States). Insights into the lived experience of MG were consolidated from three sources (a qualitative research study of 54 people with MG or their carers from seven countries; a previous Patient Council meeting [September 2019]; and a literature review). Insights were prioritised by the Patient Council, discussed during a virtual workshop (August 2020) and articulated in a series of statements organised into domains. Overarching themes that describe the lived experience of MG were identified by the patient authors.

Results

From 114 patient insights and supporting quotes, the Patient Council defined 44 summary statements organised into nine domains. Five overarching themes were identified that describe the lived experience of MG. These themes include living with fluctuating and unpredictable symptoms; a constant state of adaptation, continual assessment and trade-offs in all aspects of life; treatment inertia, often resulting in under-treatment; a sense of disconnect with healthcare professionals; and feelings of anxiety, frustration, guilt, anger, loneliness and depression.

Conclusion

This patient-driven analysis enriches our understanding of the reality of living with MG from the patient perspective.

Myasthenia gravis from the patient perspective (MP4 65175 kb)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this analysis? |

Few studies explore the impact of living with myasthenia gravis from the patient perspective. |

A greater understanding of what it means to live with myasthenia gravis may improve patient care. |

By collating and analysing patient insights, our aim was to describe the lived experience of myasthenia gravis from the patient perspective. |

What did we learn from this analysis? |

This international patient-led analysis of over 114 patient insights showed that living with myasthenia gravis significantly impacts many aspects of life. |

Five themes that describe the experience of living with myasthenia gravis were articulated by the patient authors, including: • living with fluctuating and unpredictable symptoms • a constant state of adaptation, continual assessment and trade-offs in all aspects of life • treatment inertia, often resulting in under-treatment • a sense of disconnect with healthcare professionals • feelings of anxiety, frustration, guilt, anger, loneliness and depression. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a patient author video, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19175462.

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare autoimmune disease characterised by antibody-mediated interference with neuromuscular transmission at the neuromuscular junction [1]. MG is classed as a rare disease, and its prevalence is estimated to be about 1–2 per 10,000 people [2]. However, reported incidence rates are increasing, partly due to improved diagnostic techniques and an increased awareness of the disease [3]. Despite a growing wealth of published literature, how much do we really understand about what it means to live with MG from the patient perspective?

MG manifests clinically as muscle weakness [4] and muscle fatiguability [5]. Although some patients (15%) experience ocular symptoms only, the majority (85%) have more generalised symptoms [4]. Indeed, an exacerbation of generalised muscle weakness can result in a life-threatening myasthenic crisis, requiring respiratory support [6]. Beyond muscle weakness and muscle fatiguability, many patients also report central fatigue, experienced as a lack of physical and/or mental energy, which is associated with reduced quality of life [5]. Common comorbidities for MG include dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension and other autoimmune conditions such as thyroid disease [7, 8]. Symptoms of these comorbidities, combined with side effects of their associated treatments, further add to the burden of disease experienced by people with MG.

Although the epidemiology and clinical presentation of MG are well documented, effective therapies that cure or prevent this disease remain elusive [4, 9]. Despite recent advances in the treatment of some other rare diseases [10], progress in the treatment of MG has not been rapid. Thymectomy is an effective option for patients with thymomas, and can also be considered for other patients with MG [11]. Current medications focus on managing symptoms (e.g., with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) or providing non-specific chronic immunosuppression (e.g., corticosteroids, non-steroidal immunosuppressants). Systemic biologics such as rituximab and eculizumab can be used to treat refractory disease. Plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin are fast-acting treatments typically used in conjunction with intensive care to manage myasthenic crisis [4, 6]. Ongoing clinical trials provide hope for additional treatment options in the near future [12].

Ongoing clinical research and interventional trials aim to better understand and address the physiological manifestations of MG, but they will tell us very little about what it is really like for patients to live with this rare disease. To achieve this, we need approaches that are informed by phenomenology, enabling us to explore MG from the perspective of those who have experienced it. Phenomenology encourages us to study an individual’s lived experience of the world, providing new meanings and enhancing our own understanding [13, 14]. Despite ongoing debate regarding the best methodologies, there is growing acceptance of the importance of phenomenology in medicine, especially in understanding chronic illness [15]. Such approaches rely on detailed reports of first-person experiences, gained through open dialogue during which patients are asked about their own experiences. Indeed, the importance of understanding the patient perspective and their priorities, especially in rare diseases, is recognised by the regulators, with both the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration developing initiatives to ensure an active dialogue with patients [16, 17].

By gaining a better understanding of the lived experience of MG, we can bridge any gap between healthcare providers’ (HCPs’) perceptions of MG based on objective clinical data and the patients’ perceptions of MG based on their subjective everyday experiences. An effective patient–physician relationship is particularly important for successfully managing a chronic rare disease and identifying shared treatment goals [18]. Not only will each individual patient have a unique lived experience, but their perspective of their own disease, and hence treatment goals, may also change over time [19]. Studies investigating patients’ experiences of living with MG have reported on the impact of this condition on many aspects of life, ranging from simple daily activities, such as personal hygiene and chewing food, to larger parts of an individual’s identity, such as employment and family life [20,21,22,23]. MG has also been shown to have a significant emotional and psychological impact on patients: there is a high prevalence of depression and anxiety in people living with MG [24, 25]. However, few studies have explored the first-person patient perspective to gain a detailed understanding of the multifaceted lived experience of MG [26].

The need for greater understanding of the reality of living with generalised MG was identified by a group of leading national patient advocates from around the world: the International Myasthenia Gravis Patient Council. This Patient Council, initially formed in 2018, provides advice and guidance to UCB Pharma to ensure a patient-led approach to improving treatment for people with MG. During a meeting in September 2019, the Patient Council, in collaboration with UCB Pharma, initiated a qualitative analysis of patient insights, collated from multiple sources, to create a detailed patient consensus of the lived experience of active, generalised MG. Here, we report the Patient Council analysis of collated insights and creation of detailed statements, spanning multiple aspects (domains) of life. As two authors of this article (NL and KD) are experienced patient advocates and members of the Patient Council, we went on to identify themes from the data that span domains and portray the lived experience of MG. These themes are discussed, along with some of the personal growth aspects of living with MG that were also identified from the insights. We believe that this is the first patient-led, patient-authored analysis of the lived experience of MG and hope that it will enhance understanding of this rare disease.

Methods

This analysis, initiated and funded by UCB Pharma, was led by the Patient Council: a group of people living with MG who serve as leading patient advocates in their local communities across the globe, including Europe and the United States. They are a diverse group of adult men and women who are proficient in the English language. Participating members of the Patient Council are listed in the acknowledgements.

Having previously identified a need to better understand and report the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective, the Patient Council reconvened in August 2020 to review insights collated from multiple data sources. Their objective was to generate a series of statements that, on the basis of their collective experience of MG, they felt best represented the lived experience of generalised MG.

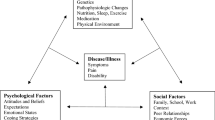

An overview of the process followed for insight identification, collation, prioritisation and analysis is shown in Fig. 1.

Insight Identification and Extraction

Insights were based on qualitative data collected directly from people with generalised MG or reported in the literature. This approach was based on that previously reported to investigate the patient perspective in another rare disease [27]. A simple framework analysis was used by two researchers to systematically gather and categorise insights from three different sources:

-

1.

A global qualitative research study of 54 people affected by MG (48 people with generalised MG and six caregivers; 39 female) from seven countries across Europe, the United States and Asia Pacific. Participants with MG were aged ≥ 18 years, had experienced generalised symptoms for ≥ 1 year (majority for > 5 years) and were currently receiving treatment. Participants were interviewed between 1 November 2019 and 31 January 2020. Although the study itself investigated all aspects of the patient journey, only patient insights and quotes focused on the ongoing management of diagnosed patients receiving treatment for MG were extracted for this analysis.

-

2.

A prior Patient Council meeting (Brussels, September 2019) report detailing discussions between six council members living with MG who serve as patient advocates in their local communities across the globe, including in Europe and the United States.

-

3.

Selected articles (32 peer-reviewed research publications, one newsletter and one book) that present patient-reported outcomes or experiences of living with MG. The articles were identified by a comprehensive search of the literature (PubMed, predetermined patient and sociology journals, articles and books) and screened for relevance by two researchers.

Further details of these data sources are provided in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

With a lack of published data describing the lived experience of MG having been acknowledged at study initiation, data from the qualitative research study of people with MG were used as the primary source of insights. These insights were supplemented with any additional relevant insights from the prior Patient Council meeting (September 2019) output. Finally, any reported insights from the literature review not already captured from the two prior sources were included. Insights were only captured once, regardless of how many times they appeared in the data sources.

During extraction of the insights, care was taken to accurately represent the source data and minimise researcher interpretation: this included cross-checking and discussion between the two researchers. Specific patient quotes were also noted to further explain the insights. The insights and quotes were then categorised into descriptive domains reflecting different aspects of the lived experience of MG. Domains were initially constructed on the basis of suggestions proposed by the Patient Council at the start of the analysis, then modified slightly by the researchers during insight extraction to provide a framework with which to present the different aspects of the lived experience of MG.

Insight Analysis by the Patient Council

Collated insights and quotes, categorised by domain, were sent to the Patient Council members for review and prioritisation via an online survey. For each insight, the survey asked the Patient Council members to consider how well the insight represented the lived experience of MG from a patient perspective (‘very well’/‘somewhat’/‘not very well’). For each domain, each Patient Council member was asked to choose the five insights that they felt best described the lived experience of MG for that domain. An open-ended comment box at the bottom of each domain asked the Patient Council members to ‘Please add any supporting comments to explain your choices, anything that’s missing, or anything you would like to add’. At the end of the survey, Patient Council members were asked ‘Are there any positive aspects of living with MG as a chronic condition which you would like to share?’.

The findings of this survey were subsequently presented by the researchers and discussed with the Patient Council during a 7-h virtual meeting in August 2020. Detailed statements representing the lived experience of MG for each domain were articulated, based on the insights. At this stage, insights could be reworded and/or merged to provide concise statements. Care was taken not to change the meaning of the insights. Quotes from people with MG considered by the Patient Council to be most descriptive of the lived experience for each domain were identified during the same online meeting.

Statements were finalised by the patient authors offline after the meeting. Each statement consisted of a succinct summary statement supported by more detailed statements to capture the nuances of the insights. Patient authors (NL and KD) subsequently met online (October 2020) to discuss the statements and draw out themes that were present across multiple domains and that they felt best described the lived experience of MG.

Neither the global qualitative study nor the Patient Council–led analysis was an investigation of clinical outcomes with any intervention. Therefore, neither ethics committee approval nor clinical trial registration was required. The patients who participated in the qualitative research study provided consent for their data to be published. Members of the Patient Council consented to the publication of their insights and analysis. All members of the 2020 Patient Council approved the statements.

Results

Insight Identification, Extraction and Analysis

In total, 114 insights and 50 supporting quotes from people with MG were identified from across the three data sources and organised into nine domains: physical; psychological; social; reproduction and parenting; activities and participation; controlled and not controlled; flare-ups and myasthenic crises; treatment burden; and unmet needs. Definitions of the key domains are provided in Table 1.

Summary Statements on the Lived Experience of MG

The Patient Council defined a total of 44 summary statements describing the lived experience of MG across nine domains, and each domain was supported by a patient quote. Summary statements and a representative quote for each domain are shown in Table 1. The detailed statements can be found in Table S3.

Key Themes Reflecting the Lived Experience

Following this Patient Council–led exercise to create the statements, the patient authors (NL and KD) reviewed the statements from across all domains and identified five overarching themes that described the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective. The detailed statements that best describe each of the themes are provided in Table 2.

Theme 1: The challenge of living with MG extends beyond managing the characteristic muscle weakness. The fluctuating and unpredictable nature of symptoms, with periods of worsening and remission, has a substantial impact on the lives of people with MG.

‘Every patient will have muscle weakness, but the difficulty to live with is that it is so unstable…the fluctuation is even worse to live with than the muscle weakness itself.’—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

Theme 2: As a consequence of living with fluctuating symptoms, people with MG navigate a constant state of adaptation to their muscle weakness. They have to make continuous assessments and trade-offs in all aspects of their life, including crucial areas such as work, family planning and treatment.

‘You feel it from the moment you wake up and you have to adjust your routines and expectations; I live day by day. Those bad days you need to prioritise the most important activities, or the most basic, and try to work with your medication.’—Person with MG in the qualitative study.

Theme 3: Despite suboptimal disease control, there can be a reluctance among both patients and HCPs to alter their comfort zone of MG treatment. Multiple factors contribute to this ‘treatment inertia’, which can result in people with MG being under-treated [28, 29]. These include a lack of consensus on what constitutes optimal disease control, concerns over potential additional side effects and the time needed to see the benefits of a change in treatment. These factors can lead to a reluctance to ‘rock the boat'. Furthermore, some patients who are not treated by a specialist can feel that their HCP does not fully understand their disease.

‘Yes, if you don’t know something is going to work, and it doesn’t work, you feel like you’ve wasted 6 months which can be very frustrating.’—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

‘We don’t want to just survive—we want to thrive.’—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

Theme 4: People with MG may feel a sense of disconnect with their HCPs. This feeling is largely driven by barriers to communication such as limited time, a gap in the perception of both disease and treatment burden and differences in treatment goals. Although HCPs may focus on managing clinically relevant symptoms and side effects, this management may not address the impact that MG has on people’s lives and the degree to which they must compensate in order to live with their symptoms.

‘There is a disconnect sometimes. One of the leading doctors in MG was quoted in a magazine saying 80% of his patients are in remission. Patients say “He may think I’m in remission, but I’m taking 20–30 mg of prednisone, I have all these side effects. It’s not adequate control.’”—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

Theme 5: MG can lead to feelings of anxiety, frustration, guilt, anger, loneliness and depression. These feelings may be driven by multiple factors, from the burden of MG symptoms themselves to social isolation, loss of control and a lack of support.

‘You can’t forget you have it, I feel tied to MG.’—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

‘I remember a time when I couldn’t go out for dinner with friends after the theatre because I was so exhausted. I cried a lot that evening.’—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

Personal Growth Aspects of Living with MG

Insights provided by five members of the Patient Council in response to the final question of the online survey identified four personal growth aspects of living with MG. These include greater resilience and empathy, increased self-awareness, a better perspective on life and an opportunity to help others. These personal growth aspects with representative quotes are provided in Table 3.

Discussion

Generalised MG has a profound impact on many aspects of the lives of those with the disease. This analysis of insights gathered from multiple sources provides a detailed description of the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective. By collating 114 different insights describing nine different domains of life, we have created a series of 44 summary statements that represent what it can mean to live with generalised MG. Clearly, every person’s experience is unique and varies over time, so these data do not accurately represent every patient with MG. However, by identifying themes that emerge from the data, supported by multiple detailed statements from across different life domains, we can begin to describe aspects of what it can mean to live with this rare disease from the patient perspective.

Although several studies have reported on the impact of muscle weakness itself [25], this being the clinical description of the disease, one of the strong emerging themes we identified from this analysis describes the experience of living with fluctuating weakness and an unpredictable body (Theme 1). As symptoms of MG can vary significantly from one day to the next, unpredictable fluctuations in muscle weakness and fatigue can be a key challenge that affects multiple areas of life, including physical, psychological and social aspects. Living with uncertainty can lead to feelings of vulnerability and can make planning extremely difficult. After a period of remission, during which people with MG may gain a sense of stability, an unexpected exacerbation of symptoms can be particularly discouraging, forcing people with MG to confront once again the limitations of their disease. This is consistent with data from a small phenomenological study in seven patients that identified overlapping themes of weakness, uncertainty and change in patients with MG [26], and reflects the experience of ‘bodily uncertainty’, which has been described in phenomenological studies of other neurological conditions [30]. Indeed, such fluctuating and unpredictable symptoms can lead to concern among patients that an assessment by their HCP during a specific consultation may not reflect their true experience of living with MG [31].

As a result of living with an unpredictable body, our analysis shows that people with MG report having to navigate a constant state of adaptation. This involves making continuous assessments and trade-offs in all aspects of their life, impacting both day-to-day and major life decisions (Theme 2). They develop and rely on coping strategies and long-term planning, while remaining flexible in order to adapt to the limitations of an unpredictable body. Consistent with published studies [22, 23, 32], our statements show that trade-offs can be significant, impacting important life choices such as family planning and career opportunities.

Indeed, our analysis indicates that some people with MG may appear to be coping well, but are actually making numerous conscious or unconscious adaptations to their lives that could be avoided if their treatment was optimised. Unfortunately, there is a level of inertia around modifying treatments for MG among both patients and their HCPs, which was evident from our statements and is captured in Theme 3. This is consistent with data from an electronic survey study in which patients reported satisfaction with their disease burden, despite being symptomatic [33]. These findings may in part be explained by a large, recent study of data from patient interviews and surveys that demonstrates the significant burden caused by the side effects of traditional MG treatments (including acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors and immunomodulating therapies) [34]. Another contributory factor may be the time it takes for some treatments to start working [35]. Indeed, our statements show that some people with MG may prefer to live with suboptimal control, choosing to make adaptations to their life rather than facing the uncertainty of changing medication. In some cases, the fear of making things worse, or causing a crisis, by changing treatment can result in people overcompensating and living with poorly controlled symptoms that can be dangerous.

In addition to treatment inertia, some people with MG report a sense of disconnect with their HCPs. Although HCPs tend to focus on managing clinically relevant symptoms and adverse events, this approach may not prioritise aspects of the condition that have the greatest impact on the lived experience. This disconnect in relation to treatment goals can result in some people with MG feeling that their HCPs don’t understand what is important to them (Theme 4), further discouraging them from seeking medical help for poorly controlled symptoms.

Our final theme describes feelings of anxiety, frustration, guilt, anger, loneliness and depression among people with MG (Theme 5). The unpredictability of MG can make planning difficult, resulting in the repeated need to cancel arrangements. This in turn can lead to feelings of loneliness, defeat and guilt about being unreliable and having to let people down. Combined with anger and frustration with the burden of both the disease and treatment, and the sense of disconnect with their HCP, it is unsurprising that depression and anxiety are common in those living with MG [25]. Such feelings may also be exacerbated by the central fatigue experienced by people with MG [36, 37].

Despite facing many challenges as described in the statements, peoples’ perspectives on life with a chronic disease such as MG may change over time. A large meta-synthesis of qualitative research reports describing patient experiences of living with a chronic illness presents a model of shifting perspectives about their disease that may not be linked to symptom exacerbation or remission, but may instead occur to enable patients to make sense of their lives [19]. Although there are no inherent clinical benefits of MG, some people do experience some sense of personal gain as a result of living with this disease, as has been reported for other chronic diseases [38] and illness-related trauma [39].

In particular, prioritised insights from our Patient Council support the view that living with MG, as with other chronic conditions, can provide an opportunity for personal growth: some patients report improved self-awareness and increased empathy. Gaining perspective was also reported, enabling patients to build resilience and reassess their priorities.

‘It helps you to figure out what really matters in your life and set priorities. Things that might have caused you stress before you nearly died in crisis become minor annoyances.’—Patient advocate, Patient Council.

Indeed, coping strategies to encourage optimism, self-reliance and feelings of control have been shown to have a positive impact on the well-being of patients with MG [40]. In addition, the opportunity for people with MG to help others and the benefits associated with this were evident in our insight analysis and have been reported elsewhere [21, 40]. Providing peer support has been shown to improve morale and self-esteem, leading to a sense of empowerment [41].

Following a patient-led approach, we have collated and prioritised insights from people living with MG to provide a comprehensive overview of the lived experience of MG. By reflecting on their extensive experience as patient advocates for their communities, the Patient Council were able to identify insights that best represent the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective. Care was taken throughout the process of insight identification, collation and prioritisation to ensure that the final statements accurately reflect the original first-person data on which they were based. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that there are a number of limitations with this approach. Despite steps to limit researcher bias throughout insight identification and collation, including cross-checking of data and close collaboration between the two researchers, this will have inevitably influenced the initial list of insights presented to the Patient Council for prioritisation. Furthermore, although a strength of this study was the extent of data sources analysed and the number of insights extracted (114 in total across three data sources), there is a risk that some insights became decontextualised during extraction and may not be applicable to other settings [42]. Finally, although the Patient Council involved in this analysis consisted of advocates from seven different countries, both male and female and representing a wide age range, a council of different advocates with different experiences may have prioritised different insights, impacting the final statements.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, we believe that this patient-led analysis provides an important portrayal of the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective. More studies that present the patient experience are needed to build on our initial findings. Such studies could explore insights from larger patient populations, as well as carers, family and close friends, from across the globe to further enrich our understanding of what it really means to live with generalised MG. We hope that this analysis and the resulting statements describing the lived experience of MG from the patient perspective will enhance HCPs’ understanding of this rare disease, thereby facilitating dialogue with patients and encouraging shared decision-making.

Change history

06 March 2022

The original version of this article was revised to include a peer-reviewed video retrospectively and to include the Digital Features text.

References

Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1023–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00145-3.

Carr AS, Cardwell CR, McCarron PO, McConville J. A systematic review of population based epidemiological studies in myasthenia gravis. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-10-46.

Westerberg E, Punga AR. Epidemiology of myasthenia gravis in Sweden 2006–2016. Brain Behav. 2020;10: e01819. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1819.

Gilhus NE, Tzartos S, Evoli A, Palace J, Burns TM, Verschuuren J. Myasthenia gravis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0079-y.

Ruiter AM, Verschuuren J, Tannemaat MR. Fatigue in patients with myasthenia gravis. A systematic review of the literature. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020;30:631–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2020.06.010.

Hogan C, Lee J, Sleigh BC, Banerjee PR, Ganti L. Acute myasthenia crisis: a critical emergency department differential. Cureus. 2020;12: e9760. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9760.

Diaz BC, Flores-Gavilán P, García-Ramos G, Lorenzana-Mendoza NA. Myasthenia gravis and its comorbidities. J Neurol Neurophysiol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9562.1000317.

Tanovska N, Novotni G, Sazdova-Burneska S, et al. Myasthenia gravis and associated diseases. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:472–8. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.110.

Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87:419–25. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000002790.

Kaufmann P, Pariser AR, Austin C. From scientific discovery to treatments for rare diseases—the view from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences—Office of Rare Diseases Research. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0936-x.

Aydin Y, Ulas AB, Mutlu V, Colak A, Eroglu A. Thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Eurasian J Med. 2017;49:48–52. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurasianjmed.2017.17009.

Lascano AM, Lalive PH. Update in immunosuppressive therapy of myasthenia gravis. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20: 102712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102712.

Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8:90–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2.

Carel H. Phenomenology and its application in medicine. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011;32:33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-010-9161-x.

Svenaeus F. A defense of the phenomenological account of health and illness. J Med Philos. 2019;44:459–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhz013.

European Medicines Agency. Patients and consumers. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/patients-consumers. Accessed 17 Feb 2021.

US Food & Drug Administration. Patient listening sessions. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-fda-patient-engagement/patient-listening-sessions. Accessed 17 Feb 2021.

Garrino L, Picco E, Finiguerra I, Rossi D, Simone P, Roccatello D. Living with and treating rare diseases: experiences of patients and professional health care providers. Qual Health Res. 2015;25:636–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315570116.

Paterson BL. The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:21–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00021.x.

Cioncoloni D, Casali S, Ginanneschi F, et al. Major motor-functional determinants associated with poor self-reported health-related quality of life in myasthenia gravis patients. Neurol Sci. 2016;37:717–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2556-3.

Chen YT, Shih FJ, Hayter M, Hou CC, Yeh JH. Experiences of living with myasthenia gravis: a qualitative study with Taiwanese people. J Neurosci Nurs. 2013;45:E3-10. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e31828291a6.

Nagane Y, Murai H, Imai T, et al. Social disadvantages associated with myasthenia gravis and its treatment: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e013278. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013278.

Frost A, Svendsen ML, Rahbek J, Stapelfeldt CM, Nielsen CV, Lund T. Labour market participation and sick leave among patients diagnosed with myasthenia gravis in Denmark 1997–2011: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0757-2.

Stewart SB, Robertson KR, Johnson KM, Howard JF Jr. The prevalence of depression in myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2007;8:111–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/CND.0b013e3180316324.

Braz NFT, Rocha NP, Vieira ÉLM, et al. Muscle strength and psychiatric symptoms influence health-related quality of life in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;50:41–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.01.011.

Keer-Keer T. The lived experience of adults with myasthenia gravis: a phenomenological study. AJON. 2015;25:40–6. https://doi.org/10.21307/ajon-2017-112.

Mathias SD, Gao SK, Miller KL, et al. Impact of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) on health-related quality of life: a conceptual model starting with the patient perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-13.

American Diabetes Association. Therapeutic inertia—a brief discussion and definition. https://professional.diabetes.org/meetings/defining-therapeutic-inertia. Accessed 24 Mar 2021.

Cutter G, Xin H, Aban I, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of the Myasthenia Gravis Patient Registry: disability and treatment. Muscle Nerve. 2019;60:707–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26695.

van der Meide H, Teunissen T, Collard P, Visse M, Visser LH. The mindful body: a phenomenology of the body with multiple sclerosis. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:2239–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318796831.

Barnett C, Bril V, Kapral M, Kulkarni A, Davis AM. A conceptual framework for evaluating impairments in myasthenia gravis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e98089. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098089.

Ohlraun S, Hoffmann S, Klehmet J, et al. Impact of myasthenia gravis on family planning: how do women with myasthenia gravis decide and why? Muscle Nerve. 2015;52:371–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24556.

Mendoza M, Tran C, Bril V, Katzberg HD, Barnett C. Patient-acceptable symptom states in myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2020;95:e1617–28. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000010574.

Bacci ED, Coyne KS, Poon JL, Harris L, Boscoe AN. Understanding side effects of therapy for myasthenia gravis and their impact on daily life. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1573-2.

Gotterer L, Li Y. Maintenance immunosuppression in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Sci. 2016;369:294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.08.057.

Tran C, Bril V, Katzberg HD, Barnett C. Fatigue is a relevant outcome in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2018;58:197–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26069.

Hoffmann S, Ramm J, Grittner U, Kohler S, Siedler J, Meisel A. Fatigue in myasthenia gravis: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Brain Behav. 2016;6: e00538. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.538.

Paterson B, Thorne S, Crawford J, Tarko M. Living with diabetes as a transformational experience. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:786–802. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129122289.

Hefferon K, Grealy M, Mutrie N. Post-traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:343–78. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708x332936.

Koopman WJ, LeBlanc N, Fowler S, Nicolle MW, Hulley D. Hope, coping, and quality of life in adults with myasthenia gravis. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2016;38:56–64.

Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, et al. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.002.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Schneider-Gold C, Hagenacker T, Melzer N, Ruck T. Understanding the burden of refractory myasthenia gravis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419832242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756286419832242.

Acknowledgements

The authors and UCB gratefully acknowledge the valued contribution of the first author, Nancy Law, who sadly passed away following preparation of this manuscript (Thursday, 23 September 2021). Nancy was instrumental in driving this important analysis to ensure that the voices of people living with myasthenia gravis are clearly heard. Her passion for and dedication to improving the lives of people living with myasthenia gravis will continue to be an inspiration to us all. We give special thanks to the people with MG who participated in the qualitative research survey. We thank the members of the International Myasthenia Gravis Patient Council: Patient Council September 2019: Johan Voerman (Netherlands); Claudia Schlemminger (Germany); Nancy Law (USA); Eva Frostell (Finland); Marguerite Friconneau (France); Annie Archer (France); Laura Maria Julia Calvo (Spain); Kelly Davio (UK). Patient Council August 2020 and pre-meeting survey: Annie Archer (France); Kelly Davio (UK); Eva Frostell (Finland); Hilde Kerkhofs (Belgium); Nancy Law (USA); Louis Loontjens (Belgium); Matthieu Luisgnan (France); Raquel Pardo Gomez (Spain); Johan Voerman (the Netherlands).

Funding

This study was funded by UCB Pharma (Brussels, Belgium). The journal’s rapid service fee was also funded by UCB Pharma (Brussels, Belgium).

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

Branding Science Ltd. conducted the qualitative research survey, funded by UCB Pharma. Jenny Hepburn and Dawn Lobban, of Envision Pharma Group, performed the literature search, analysed the primary data sources, compiled the insights and facilitated the Patient Council survey and discussion, funded by UCB Pharma. Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Dawn Lobban, PhD, of Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by UCB Pharma. Veronica Porkess, PhD, of UCB Pharma, also provided publication and editorial support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Dawn Lobban performed the role of researcher in this analysis. All authors were involved in the study design, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. As members of the Patient Council, Nancy Law and Kelly Davio were also involved in the insight selection and discussion. No funding was provided for authorship.

Prior Presentation

This manuscript is based on work that has been presented as a poster presentation at The American Association of Neurology Annual Meeting, 2021. Law N, Davio K, Blunck, M, et al. The lived experience of myasthenia gravis: A patient-led analysis. Poster presentation at the AAN Virtual Annual Meeting; 17–22 April 2021.

Disclosures

Nancy Law and Kelly Davio are members of the Patient Council. Melissa Blunck and Kenza Seddik are employees of UCB Pharma, which funded the study. Dawn Lobban is an employee of Envision Pharma Group, which was funded by UCB Pharma to support with the analysis and medical writing support.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Neither the global qualitative study nor the Patient Council–led analysis was an investigation of clinical outcomes with any intervention. The global qualitative study adhered to local market research guidelines in the countries included and was conducted in accordance with EphMRA Code of Conduct. Therefore, neither ethics committee approval nor clinical trial registration was required. The patients who participated in the qualitative research study were fully informed of the purpose of research, provided consent to participate and agreed for their data to be published. Members of the Patient Council consented to the publication of their insights and analysis.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included as supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Deceased: Nancy Law.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Law, N., Davio, K., Blunck, M. et al. The Lived Experience of Myasthenia Gravis: A Patient-Led Analysis. Neurol Ther 10, 1103–1125 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00285-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00285-w