Abstract

This article describes consensus recommendations from an expert group of neurologists from the Arabian Gulf region on the management of relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) in the COVID-19 era. MS appears not to be a risk factor for severe adverse COVID-19 outcomes (though patients with advanced disability or a progressive phenotype are at higher risk). Disease-modifying therapy (DMT)-based care appears generally safe for patients with MS who develop COVID-19 (although there may be an increased risk of adverse outcomes with anti-CD20 therapy). Interferon-β, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab and cladribine tablets are unlikely to increase the risk of infection; fingolimod, anti-CD20 agents and alemtuzumab may confer an intermediate risk. Existing DMT therapy should be continued at this time. For patients requiring initiation of a DMT, all currently available DMTs except alemtuzumab can be started safely at this time; initiate alemtuzumab subject to careful individual risk–benefit considerations. Patients should receive vaccination against COVID-19 where possible, with no interruption of existing DMT-based care. There is no need to alter the administration of interferon-β, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, fingolimod or cladribine tablets for vaccination; new starts on other DMTs should be delayed for up to 6 weeks after completion of vaccination to allow the immune response to develop. Doses of the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine may be scheduled around doses of anti-CD20 or alemtuzumab. Where white cell counts are suppressed by treatment, these should be allowed to recover before vaccination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) appears not to be a risk factor for severe adverse COVID-19 outcomes per se in the absence of advanced disability or a progressive phenotype. |

Disease-modifying therapy (DMT)-based care is generally safe for patients with MS who develop COVID-19 (more research is needed for anti-CD20 therapies, which may be associated with severe COVID-19). |

All currently available DMTs except alemtuzumab can be started safely at this time (careful individual risk–benefit consideration is needed for alemtuzumab). |

There is no need to alter the administration of interferon-β, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, fingolimod or cladribine tablets for vaccination against COVID-19. |

Delay new starts on other (high-efficacy) DMTs for up to 6 weeks after completion of vaccination (allow white cell counts to recover where applicable). |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14635935.

Introduction: COVID-19 in the Arabian Gulf

COVID-19 in the Arabian Gulf

The COVID-19 pandemic reached countries in the Arabian Gulf in February 2020. Initial cases were imported from the proposed location of the source of the virus in Wuhan, China, followed by clusters of cases associated with travel between Gulf countries and Iran [1, 2]. Countries in the region responded quickly with measures to suppress transmission of the virus. Measures undertaken included restrictions on international travel, restrictions of internal travel, closure of educational institutions and mosques, and restrictions on public gathering in leisure, sporting and retail settings. Later, local lockdowns (with or without evening/night-time curfews) were introduced in a number of cities. Testing facilities for detecting cases of COVID-19 were introduced (the UAE was an early adopter of drive-through testing centres to minimise person-to-person contact).

Similar measures have been adopted in virtually all countries during the past year [3]. The rate of new cases reported in the previous 24 h at the time of writing by the World Health Organization (WHO) is now variable between Gulf countries, and overlaps the rate seen in major economies around the world (Fig. 1a) [4, 5]. The number of deaths/million population associated with COVID-19 has been low for Gulf countries, compared with most of these other countries, perhaps indicating some success over the duration of the pandemic [4, 5].

Current status of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arabian Gulf in comparison with selected nations from other regions of the world. Data on new cases of COVID-19 were reported during the previous 24 h according to the World Health Organization (WHO) for March 13, 2021 [4]. Population figures were from Worldometer [5]. Rates per million population are unadjusted. KSA Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, UK United Kingdom, USA Unites States of America

Rationale and Methods for this Article

Mass vaccination programmes with novel anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines now provide hope for an end to the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the clinical landscape will eventually tend to an as yet only partially understood “new normal”. This is of great concern to physicians and patients, including those with long-term non-communicable diseases that need lifelong treatment. The care of relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) represents a special case within this group, as the disease-modifying treatments we prescribe interact with, and sometimes suppress, the immune system.

We, an expert group of specialist neurologists from five countries within the Arabian Gulf, met virtually to consider the impact of COVID-19 on care for RMS, and provide our consensus recommendations for the future management of RMS in the COVID-19 era, including on the use of DMTs and how and when to administer anti-COVID-19 vaccinations.

Literature was identified by searching PubMed using search terms such as “Covid”, “multiple sclerosis” and “disease modifying therapy”, as well as individual DMTs. Authors also contributed literature of potential interest. An informal consensus procedure was performed, where experts voted on issues relating to MS care and the use of DMTs. We did not use a formal methodology for expressing consensus. We show the number of votes cast for a given proposition where there was not complete agreement, to illustrate the strength or otherwise of a consensus. This article is intended to provide guidance to practising physicians in a novel, complex and changing situation. We have not allocated a grade or strength of evidence or strength of recommendation, because evidence is lacking in most areas. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

COVID-19 and Multiple Sclerosis

Impact of COVID-19 on Management of Multiple Sclerosis

Healthcare systems in the Middle East and elsewhere around the world have been put under immense stress by the sudden influx of people with COVID-19, who may often require intensive care and possibly assisted ventilation [3, 6]. Diversion of physicians and other resources from other areas of medicine has led to postponement or suspension of routine care for populations with a range of with non-communicable diseases, even in advanced economies, with potentially adverse consequences for long-term patient outcomes [7, 8].

The relatively robust and advanced medical infrastructure of countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council have left these states reasonably well prepared to cope with these challenges [9]. Nevertheless, the authors have noted constraints on their own neurology practice, consistent with the issues described above, which affect both physicians and patients (Table 1). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed medical practice, perhaps forever.

Management of Multiple Sclerosis in the COVID-19 Era

Risk Factors for Serious Adverse COVID-19 Outcomes

The principal risk factors for adverse COVID-19 outcomes (e.g. hospitalisation, need for intensive care, or death) in cohort studies of general populations have included male gender, ethnicity, higher age, obesity, hypertension, multiple comorbidities (including neoplasms, cardiovascular disease, diabetes or obstructive airways disease) and lymphopenia or leukopenia [10,11,12,13,14]. Any patient with MS may have one of more of these risk factors, which appear to exert similar effects on outcomes as people without MS [15]. The presence of these risk factors may influence aspects of management, perhaps especially vaccination against COVID-19 (see below). Most available evidence suggests that a diagnosis of RMS per se does not appear to confer increased risk either of catching COVID-19, or of a more severe, adverse outcome if a patient does contract COVID-19 [16,17,18,19,20].

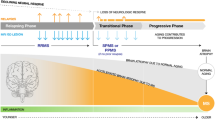

Progressive MS [16], and possibly advanced disability in people with MS [21], has been identified as a risk factor for a potentially severe adverse COVID-19 outcome, however. In addition, concern over COVID-19 has been identified as a source of fear and anxiety in patients with MS [22], and physicians may need to provide reassurance on the lack of association between MS and adverse COVID-19 outcomes. Another study proposed reduced physical activity during lockdowns as an important mediator of reduced psychological health among people with MS [23].

Recommendations for Use of Disease-Modifying Treatments in Management of Multiple Sclerosis in the Arabian Gulf

Current Evidence

In theory, DMTs that induce immunosuppression might increase the risk of adverse long-term outcomes in people with MS who develop COVID-19. Published data on the association between receipt of a DMT for RMS and clinical outcomes in people with COVID-19 are limited at present, and much of the available data are in presentations rather than peer-reviewed publications. Nevertheless, DMT-based therapy for people with RMS in general does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 or developing a severe adverse COVID-19 outcome [15, 18, 19, 24,25,26,27]. There is a suggestion that COVID-19 outcomes may have been more severely adverse in people with MS who received treatment with anti-CD20 agents (ocrelizumab, ofatumumab or rituximab) for MS, compared with other DMTs [15, 28,29,30], although this has not been a universal finding [31,32,33]. More severe COVID-19 associated with anti-CD20 therapies has also been observed in patients receiving an anti-CD20 agent for conditions other than MS [34, 35].

Gulf Expert Opinion

Generally, most DMTs were not considered by the authors to be associated with an increased risk of contracting COVID-19. We proposed a higher, intermediate risk for alemtuzumab and anti-CD20 agents (Table 2; Fig. 2); this is based on the known increase in susceptibility to viral infections in general, compared with other DMTs, and does not apply to an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 at this time. Expert opinion was unanimous, or near unanimous, in favour of starting new treatment or continuing existing treatment at this time with glatiramer acetate, interferon-β, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, natalizumab, fingolimod or cladribine tablets (Table 2; Fig. 3). Extended interval (e.g. 6 weekly) dosing with natalizumab does not appear to reduce the efficacy of this DMT [36], and is an option where MS disease activity is well controlled on this treatment. Support for starting anti-CD20 treatment was less strong, and there was no consensus in favour of initiating or continuing treatment with alemtuzumab (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Average of experts’ responses to the question, “In your opinion, does the use of following DMTs increase the risk of infection with COVID-19?” Experts responded to the question with an integer rating of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and bars are the mean of these ratings. “High-efficacy” disease-modifying therapies (DMTs, as categorised by the authors) are shown in dark blue; “platform” or “first-line” DMTs are shown in light blue

The authors’ recommendations were generally consistent with the labelling for these DMTs (Table 3). Interferon-β, glatiramer acetate and teriflunomide are not strongly associated with an increased risk of serious infections in their European labels, although some opportunistic infections are noted as a side effect of glatiramer acetate. High-efficacy DMTs are associated more strongly with an increased risk of infections, including reactivation of latent infections (Table 3). Confidence in initiating or continuing alemtuzumab was lower because of the challenging safety profile of this DMT, and its association with prolonged lymphopenia after administration (lymphocytes were suppressed for about 6 months after each administration of alemtuzumab in the CARE MS I and CARE MS II phase III trials [37]). Current guidance from the MS International Federation considered that evidence is insufficient to evaluate the place of alemtuzumab in MS care at this time [38]. Patients who are due for a course of treatment with alemtuzumab should discuss the timing of this with their healthcare practitioner (advice is similar for cladribine tablets and anti-CD20 agents) [38].

Vaccinating People with Multiple Sclerosis Against COVID-19

Overview of COVID-19 Vaccines Available in the Arabian Gulf

The development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 is proceeding worldwide at an unprecedented rate. As of March 16, 2021, 42 such vaccines were described as being in phase I clinical evaluation, with 32 and 22 further candidate vaccines in phase II and phase III, respectively [39]. Table 4 describes the main characteristics of seven anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines already in clinical use [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. These vaccines vary considerably in their underlying technology, and generate antigens that resemble a segment of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in vivo via delivery of modified mRNA using liposomes (Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna), DNA delivered by a recombinant adenoviral vector that is incapable of replication (Oxford University/AstraZeneca [OxAZ], Sputnik V, Janssen), a peptide fragment (Novavax), or inactivated virus produced in cultured cells (Sinopharm).

Multiple vaccines are available in the Arabian Gulf. Importantly, none of these vaccines contain live or attenuated live virus that is capable of replication and/or initiation of COVID-19 infection in vivo, including in an immunocompromised patient. At present, we have no data on which vaccine(s) might be most or least appropriate for use in people with MS, and this would be an interesting topic for future research when more data are available.

Recommendations on Vaccination Against COVID-19 for People with Multiple Sclerosis in the Arabian Gulf

Advice on vaccination in the labelling for DMTs, where given, relates to routine local vaccination practice or to prophylactic vaccination against opportunistic or latent infections (Table 3). Live or attenuated live vaccines should be avoided during treatment with most DMTs for fear of initiating an infection in a patient whose immune status has been compromised by a treatment that induces prolonged or permanent immunosuppression (Table 3); this is not a concern for current COVID-19 vaccines, as described above. There are currently few data on the immunologic response to a COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving a DMT for MS, although in theory long-term immunosuppression might reduce a vaccine’s effectiveness. Studies of responses to other vaccinations will be reviewed briefly here, to consider the effects of these treatments on the response to vaccination per se.

Table 5 shows our recommendations on vaccination against COVID-19 for a patient either starting a new DMT or already receiving a DMT. The effect of a first-line DMT (interferon-β, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, glatiramer acetate) on the efficacy of a vaccination is likely to be small or absent, and vaccination should proceed irrespective of the DMT treatment plan [50,51,52,53,54]. Natalizumab has also been shown not to diminish the response to other vaccines [55], and new or continued treatment with this agent is also no barrier to accessing vaccination against COVID-19. It is important not to stop treatment with natalizumab for vaccination, as this may provoke MS disease reactivation [56]. In addition, our recommendations on vaccination have been designed to accommodate the administration regimen of cladribine tablets, and no change to this regimen is required. Data from patients with MS has demonstrated adequate responses to other vaccines during years 1 and 2 of treatment with cladribine tablets irrespective of the duration from the last dose and the lymphocyte count [57, 58], and this needs to be confirmed with regard to vaccinations for COVID-19, with special reference to the timings of administration of the DMT and the vaccine.

Treatment of people with MS with fingolimod [59] or ocrelizumab [60] has been shown to blunt the response to vaccination. However, these patients were still able to develop a worthwhile immune response to vaccination. A case–control study reported adequate response to commonly used vaccines 1 month and 9–11 months after treatment with alemtuzumab [61]. Clinical experience with the new COVID-19 vaccines suggests that their efficacy in preventing severe adverse COVID-19 outcomes is greater than their ability to prevent uncomplicated, symptomatic infections [40] and even a blunted vaccine response may save your patient’s life: accordingly, vaccination of these patients should be carried out where possible, subject to due consideration of benefits and risks. Treatment with these DMTs should not be stopped or interrupted for vaccination (note also that withdrawal of fingolimod may provoke severe MS disease reactivation [62]). Vaccine doses should be scheduled before and after infusions of ocrelizumab.

For new starts on DMT therapy, we recommend a delay between completion of a course of vaccination (other than the OxAZ vaccine, see below) of 4–6 weeks before initiation of fingolimod or an anti-CD20 DMT, in order to allow the immunological response to vaccination to develop fully (Table 5). Vaccination of patients who have received alemtuzumab should occur when white blood cell counts have returned to the normal range (Table 5).

The OxAZ vaccine differs from other vaccines for COVID-19 in that a pre-specified analysis of its phase 3 programme demonstrated substantial (and increasing) immunity against COVID-19 for the 3 months following the initial dose [63]. These data confirmed that extended interdose intervals are safe and effective for this vaccine, providing an opportunity to vaccinate either side of a first or subsequent treatment with anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab, thus minimising the delay in initiating DMT therapy or the course of an ongoing DMT regimen (Table 5). These recommendations provide a pragmatic compromise between facilitating vaccination against COVID-19 and minimising disruption of DMT-based therapy to maintain protection against MS relapses and progression of disability.

Overall, current evidence and guidance is clear that vaccination is likely to produce worthwhile immune responses during treatment of MS with a DMT, that the risk of harm from vaccination of a patient with MS is negligible, that the benefits of vaccination clearly outweigh any risks, and that people with MS should receive a vaccination against COVID-19 where possible [50, 51]. The labelling for DMTs used in MS care will need to be updated with specific information on vaccination against COVID-19 as soon as more data are available.

Summary and future perspectives

Box 1 provides a summary of our recommendations regarding the management of patients with RMS during the COVID-19 pandemic, and regarding the deployment of vaccination against COVID-19. We have not used formal consensus procedures, nor formal grading of evidence or strength of recommendations. This is a limitation of our approach, but these are pragmatic recommendations based on expert opinion in light of the limited and incomplete data available at this time.

RMS has not emerged as a risk factor for severe adverse COVID-19 outcomes per se, although patients with more advanced disability and a progressive MS phenotype seem to be at higher risk. Importantly, treatment with a DMT and vaccination against COVID-19 appear to be safe in people with MS, on the basis of the data we have today, and we have provided a pragmatic series of suggestions for dovetailing vaccination with DMT-based MS care. Precise practices regarding vaccination of people with MS on different DMTs will be refined as more clinical data become available. It is important to remember that risk factors for severe adverse COVID-19 outcomes (e.g. obesity, older age, male gender, some comorbid conditions) will be present in many patients with MS. Vaccinating these patients, in particular, against COVID-19 is an important clinical priority.

Education of the public will be crucial to maximise uptake of vaccines against COVID-19. This includes healthcare professionals: a recent survey from Saudi Arabia found that half of a population of 763 “healthcare workers” (otherwise undefined) would not accept vaccination as soon as a vaccine became available [64], a proportion almost identical to that from the general population [65]. Perceived concerns over the level of demonstration of safety for the vaccines were important here. This “vaccine hesitancy” has also been noted in populations of patients with MS, as there has long been an unfounded concern that vaccination may exacerbate MS [66, 67]. Indeed, it has been suggested that, as infections and fever are known to bring on MS relapses, prevention of febrile infections might improve the overall course of MS [66].

References

Alandijany TA, Faizo AA, Azhar EI. Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries: current status and management practices. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(6):839–42.

Alabdulkarim N, Alsultan F, Bashir S. Gulf countries responding to COVID-19. Dubai Med J. 2020;3:58–60.

Walker PGT, Whittaker C, Watson O, et al. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. The impact of COVID-19 and strategies for mitigation and suppression in low- and middle-income countries. Science. 2020;369:413–22.

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/table. Accessed Mar 2021.

Data from worldometer. https://www.worldometers.info/. Accessed Mar 2021.

Duran D, Menon R, on behalf of the World Bank. Mitigating the impact of COVID-19 and strengthening health systems in the Middle East and North Africa. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34238. Accessed Mar 2021.

Saab R, Obeid A, Gachi F, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on pediatric oncology care in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia region: a report from the Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) group. Cancer. 2020;126(18):4235–45.

Rowles R, Patel D, Macklin A, Dashora U. ABCD Survey: Life as a diabetologist during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Diabetes. 2020;20:163–5.

European Council on Foreign Relations. Middle East and North Africa. Infected: the impact of the coronavirus on the Middle East and North Africa. 19 March 2020. https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_infected_the_impact_of_the_coronavirus_on_the_middle_east_and_no/. Accessed Mar 2021.

Jimenez-Solem E, Petersen TS, Hansen C, et al. Developing and validating COVID-19 adverse outcome risk prediction models from a bi-national European cohort of 5594 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3246.

Xu PP, Tian RH, Luo S, et al. Risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes with COVID-19 in China: a multicenter, retrospective, observational study. Theranostics. 2020;10:6372–83.

Mallapati S. The coronavirus is most deadly if you are older and male—new data reveal the risks. Nature. 28 August 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02483-2. Accessed Mar 2021.

Figliozzi S, Masci PG, Ahmadi N, et al. Predictors of adverse prognosis in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50:e13362.

Booth A, Reed AB, Ponzo S, et al. Population risk factors for severe disease and mortality in COVID-19: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0247461.

Sormani MP, De Rossi N, Schiavetti I, et al. Disease-modifying therapies and coronavirus disease 2019 severity in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26028.

European Multiple Sclerosis Platform. Global COVID-19 advice for people with MS. 13 January 2021. http://www.emsp.org/news-messages/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-and-multiple-sclerosis/. Accessed Mar 2021.

Mallucci G, Zito A, Baldanti F, et al. Safety of disease-modifying treatments in SARS-CoV-2 antibody-positive multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;49:102754.

REDONE.br – Neuroimmunology Brazilian Study Group Focused on COVID-19 and MS. Incidence and clinical outcome of Coronavirus disease 2019 in a cohort of 11,560 Brazilian patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520978354.

Sepúlveda M, Llufriu S, Martínez-Hernández E, et al. Incidence and impact of COVID-19 in MS: a survey from a Barcelona MS unit. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8:e954.

Sahraian MA, Azimi A, Navardi S, Ala S, Naser Moghadasi A. Evaluation of the rate of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and death among Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102472.

Fernandes PM, O’Neill M, Kearns PKA, et al. Impact of the first COVID-19 pandemic wave on the Scottish Multiple Sclerosis Register population. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:276.

Ramezani N, Ashtari F, Bastami EA, et al. Fear and anxiety in patients with multiple sclerosis during COVID-19 pandemic; report of an Iranian population. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;50:102798.

Costabile T, Carotenuto A, Lavorgna L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and mental distress in multiple sclerosis: implications for clinical management. Eur J Neurol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14580.

Chaudhry F, Bulka H, Rathnam AS, et al. COVID-19 in multiple sclerosis patients and risk factors for severe infection. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117147.

Merck Safety Database (information on Covid-19 outcomes in patients treated with interferon-β1a or cladribine tablets). Merck Healthcare KGaA, data on file.

Sharifian-Dorche M, Sahraian MA, Fadda G, et al. COVID-19 and disease-modifying therapies in patients with demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system: a systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;50:102800.

Zabalza A, Cárdenas-Robledo S, Tagliani P, et al. COVID-19 in multiple sclerosis patients: susceptibility, severity risk factors and serological response. Eur J Neurol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14690.

Hillert J. Presentation at iWiMS MS Covid-19 meeting—May 13 2020. https://multiple-sclerosis-research.org/2020/05/mscovid19-swedish-experience/. Accessed Mar 2021.

Simpson-Yap S, De Brouwer E, Kalincik T, et al. First results of the COVID-19 in MS Global Data Sharing Initiative suggest antiCD20 DMTs are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. Abstract SS02–4.04, presented at the MSVirtual2020: 8th Joint ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS Meeting. https://msvirtual2020.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SS02.04.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021.

Möhn N, Konen FF, Pul R, et al. Experience in multiple sclerosis patients with Covid-19 and disease-modifying therapies: a review of 873 published cases. J Clin Med. 2020;9:4067.

Roche. Ocrevus and Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in multiple sclerosis. https://medinfo.roche.com/content/dam/medinfo/documents/Covid-19/Ocrevus_GL-019956.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021.

Hughes R, Pedotti R, Koendgen H. COVID-19 in persons with multiple sclerosis treated with ocrelizumab—a pharmacovigilance case series. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;42:102192.

Parrotta E, Kister I, Charvet L, et al. COVID-19 outcomes in MS: observational study of early experience from NYU Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7:e835.

Duléry R, Lamure S, Delord M, et al. Prolonged in-hospital stay and higher mortality after Covid-19 among patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with B-cell depleting immunotherapy. Am J Hematol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26209.

Quartuccio L, Treppo E, Binutti M, Del Frate G, De Vita S. Timing of rituximab and immunoglobulin level influence the risk of death for COVID-19 in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab175.

Zhovtis Ryerson L, Frohman TC, Foley J, et al. Extended interval dosing of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:885–9.

Li Z, Richards S, Surks HK, Jacobs A, Panzara MA. Clinical pharmacology of alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 immunomodulator, in multiple sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;194:295–314.

MS International Federation. MS, the coronavirus and vaccines – updated global advice (updated March 15 2021). https://www.msif.org/news/2020/02/10/the-coronavirus-and-ms-what-you-need-to-know. Accessed Mar 2021.

Zimmer C, Corun J, Wee S-L. Coronavirus vaccine tracker (updated March 16 2021). New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html. Accessed Mar 2021.

Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111.

Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397:671–81.

Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–16.

Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–15.

Reuters. Sinopharm’s COVID-19 vaccine 79% effective, seeks approval in China. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-vaccine/sinopharms-covid-19-vaccine-79-effective-seeks-approval-in-china-idUSKBN2940C8. Accessed Mar 2021.

National Institutes of Health. Janssen investigational COVID-19 vaccine: interim analysis of Phase 3 clinical data released. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/janssen-investigational-covid-19-vaccine-interim-analysis-phase-3-clinical-data-released. Accessed Mar 2021.

Mahase E. Covid-19: Novavax vaccine efficacy is 86% against UK variant and 60% against South African variant. https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n296. Accessed Mar 2021.

World Health Organization. Background document on the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) against COVID-19. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1330343/retrieve. Accessed Mar 2021.

Centers for Disease Control. Different COVID-19 Vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines.html. Accessed Mar 2021.

World Health Organisation. COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines. Accessed Mar 2021.

MS Society (UK). MS Society Medical Advisers consensus statement on MS treatments and COVID-19 vaccines (updated Jan 6 2021). https://www.mssociety.org.uk/what-we-do/news/ms-society-medical-advisers-release-consensus-statement-covid-19-vaccines. Accessed Mar 2021.

National MS Society. COVID-19 vaccine guidance for people living with MS. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/coronavirus-Covid-19-information/multiple-sclerosis-and-coronavirus/Covid-19-vaccine-guidance. Accessed Mar 2021.

Metze C, Winkelmann A, Loebermann M, et al. Immunogenicity and predictors of response to a single dose trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine in multiple sclerosis patients receiving disease-modifying therapies. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:245–54.

Bar-Or A, Freedman MS, Kremenchutzky M, et al. Teriflunomide effect on immune response to influenza vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81:552–8.

Zheng C, Kar I, Chen CK, et al. Multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapy and the COVID-19 pandemic: implications on the risk of infection and future vaccination. CNS Drugs. 2020;34:879–96.

Kaufman M, Pardo G, Rossman H, Sweetser MT, Forrestal F, Duda P. Natalizumab treatment shows no clinically meaningful effects on immunization responses in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2014;15(341):22–7.

Prosperini L, Kinkel RP, Miravalle AA, Iaffaldano P, Fantaccini S. Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419837809.

Roy S, Boschert U. Analysis of influenza and varicella zoster virus vaccine antibody titers in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets. Abstract P059 presented at the ACTRIMS Virtual Forum 2021. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/9245/session/23. Accessed Mar 2021.

Wu GF, Boschert U, Hayward B, Lebson LA, Cross AH. Evaluating the impact of cladribine tablets on the development of antibody titres: interim results from the CLOCK-MS Influenza Vaccine Sub-Study. Abstract P071 presented at the ACTRIMS Virtual Forum 2021. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/9245/session/23. Accessed Mar 2021.

Kappos L, Mehling M, Arroyo R, et al. Randomized trial of vaccination in fingolimod-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84:872–9.

Bar-Or A, Calkwood JC, Chognot C, et al. Effect of ocrelizumab on vaccine responses in patients with multiple sclerosis: the VELOCE study. Neurology. 2020;95:e1999–2008.

McCarthy CL, Tuohy O, Compston DA, Kumararatne DS, Coles AJ, Jones JL. Immune competence after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81:872–6.

Barry B, Erwin AA, Stevens J, Tornatore C. Fingolimod rebound: a review of the clinical experience and management considerations. Neurol Ther. 2019;8:241–50.

Voysey M, Costa Clemens SA, Madhi SA, et al. Single-dose administration and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a pooled analysis of four randomised trials. Lancet. 2021;397:881–91.

Qattan AMN, Alshareef N, Alsharqi O, Al Rahahleh N, Chirwa GC, Khaled Al-Hanawi M. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.644300.

Alfageeh EI, Alshareef N, Angawi K, Alhazmi F, Chirwa GC. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among the Saudi population. Vaccines. 2021;9:226.

Reyes S, Ramsay M, Ladhani S, et al. Protecting people with multiple sclerosis through vaccination. Pract Neurol. 2020;20:435–45.

Zrzavy T, Kollaritsch H, Rommer PS, et al. Vaccination in multiple sclerosis: friend or foe? Front Immunol. 2019;10:1883.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Merck Serono Middle East FZ Ltd funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. Co-authors did not receive payment for contributing to this article.

Editorial Assistance

A medical writer (Dr Mike Gwilt, GT Communications) provided editorial assistance, funded by Merck Serono Middle East FZ LTD, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. The authors of the article remained in control of its content throughout.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design, content and interpretation of data in the article, participated in its drafting and critical revision for intellectual content, and approved the final version for submission.

Disclosures

This article arose from discussions at a closed virtual meeting funded by Merck Serono Middle East FZ Ltd, an affiliate of Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Additionally, Dr Raed Alroughani received honoraria as a speaker and for serving in scientific advisory boards from Bayer, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr Abdullah Al-Asmi received honoraria for serving on scientific advisory boards from Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi, and also received travel reimbursement from, Biologix, Sanofi, Merck, Roche, Bayer and Novartis. Dr Abdullah Alsalti received honoraria as a speaker from Novartis, Sanofi and Merck, and served on the scientific advisory boards of Sanofi and Merck. Dr Amir Boshra is an employee of Merck Serono Middle East FZ Ltd, Dubai, UAE, an affiliate of Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Dr Beatriz Canibano has received travel, speaker and consultant honoraria from Merck, Novartis, Biologix, Roche and Sanofi. Dr Dirk Deleu has served on Served on Advisory Boards of Merck, Novartis, Biologix, Roche and Sanofi and is a member of MENACTRIMS. Dr Ahmed Osman Shatila reports honoraria for lectures (Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck, Genpharm, Roche, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biologix) and for advisory boards (Sanofi-Genzyme, Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Biologix); educational conferences travel and registration and hotel accommodation has been sponsored by Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck, Genpharm, Roche, Novartis, Biologix. Drs Jaber Alkhaboury, Jihad Inshasi, Samar Farouk Ahmed, and Mona Thakre reported no additional duality of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Inshasi, J., Alroughani, R., Al-Asmi, A. et al. Expert Consensus and Narrative Review on the Management of Multiple Sclerosis in the Arabian Gulf in the COVID-19 Era: Focus on Disease-Modifying Therapies and Vaccination Against COVID-19. Neurol Ther 10, 539–555 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00260-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00260-5