Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease in which the immune system attacks the central nervous system, causing inflammation and neurodegeneration. People living with MS may experience a variety of symptoms as a consequence of this process, including many “invisible” symptoms that are internally manifested and not seen by others. Of the invisible symptoms of MS, which we have reviewed in a companion article, mood and mental health disorders are of particular concern due to their high prevalence and significant impact on patient quality of life. In this review, we showcase the experiences of patient authors alongside perspectives from healthcare provider authors as we promote awareness of the common mental health conditions faced by those living with MS, such as depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, and suicidal ideation. Many of these conditions stem in part from the increased stress levels and the many uncertainties that come with managing life with MS, which have been exacerbated by the environment created by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. A patient-centered interdisciplinary approach, routine screening for mental health changes, and referral to specialists when needed can normalize discussions of mental health and increase the likelihood that people living with MS will receive the support and care they need. Management techniques such as robust social support, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, and/or pharmacotherapy may be implemented to build resilience and promote healthy coping strategies. Increasingly, patients have access to telehealth options as well as digital apps for mental health management. Taken together, these approaches form an integrative care model in which people living with MS benefit from the care of medical professionals, a variety of support networks/resources, and self-management techniques for optimal mental health care.

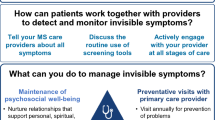

Graphical Plain Language Summary

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

People living with multiple sclerosis (MS) experience mood and mental health disorders at greater rates than the general population; this component of the ‘invisible’ symptoms of MS can significantly impact quality of life. |

Mental health disorders may be consequences of lesions of the central nervous system, the interplay of invisible symptoms, and the stress and uncertainty of living with MS. |

Mental health discussions may be incorporated into routine MS care via clinical interview and regular use of screening tools to monitor the presence and level of changes; referral to specialists should be offered when necessary. |

Initial management may utilize non-pharmacotherapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, or other strategies which build resilience. |

Integrative care models may include many team members and may help people living with MS reap the benefits of medical professionals from multiple disciplines, their own mental health self-management techniques, and support from both personal networks and patient groups/societies. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and a graphical plain language summary, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14141468.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive autoimmune disease in which loss of myelin sheaths on neurons and subsequent neurodegeneration result in increased disability for patients over time. People living with MS experience a variety of symptoms [1], some of which are externally visible to others and thus have become commonly associated with MS (e.g., difficulty walking), but others remain ‘invisible’ since they are experienced internally [2, 3]. Frequently experienced invisible symptoms, reviewed separately in a companion article [4], may include fatigue, mood and mental health disorders, cognitive changes, pain, bowel/bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and vision changes. In 2015, the American Academy of Neurology declared 11 quality measures for the care of those living with MS, four of which screen for invisible symptoms including depression, cognition, and fatigue [5]. Despite this, awareness of invisible symptoms is variable, and this could lead to misunderstandings, stigma, and gaps in care/accommodations [4, 6].

In this review, we focus on mood and mental health disorders, as they are a vital component of overall health yet are often overlooked. People living with MS are more likely than the general population to experience certain mood and mental health disorders; these conditions can include, but are not limited to, elevated/chronic stress levels, depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder, psychosis, and suicidal ideation [7, 8]. Depression and stress can also exacerbate the difficulties of managing bipolar disorder, which may be more prevalent in people living with MS [9]. Evidence suggests that the state of one’s mental health impacts quality of life (QoL) and possibly MS disease progression itself [10,11,12]. However, mental health concerns for people living with MS may be under-recognized and under-treated [13, 14]. The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may further exacerbate mental health challenges for people living with MS because of additional barriers to social interaction, interrupted routines, reduced options for safe physical exercise, and increased financial uncertainty for many families [15]. Indeed, in a study conducted during April 2020, individuals with MS reported experiencing elevated levels of depression/anxiety during the pandemic relative to their own scores 1 year prior and to healthy controls [16]. As such, the pandemic may further increase the need for awareness of and solutions for mental health issues for people living with MS.

Here, we leverage the experience of our patient authors, clinical practice, and scientific literature to examine the current understanding of mental health for people living with MS and how best to improve patient outcomes. Cherie Binns, diagnosed with MS in 1994, is a Registered Nurse (RN) and a Multiple Sclerosis Certified Nurse (MSCN). Keisha Currie, diagnosed with MS in 2012, has a master’s degree in rehabilitation counseling (MRC) and is a Certified Rehabilitation Counselor (CRC). Their insights contribute to our understanding that MS care teams should normalize mental health concerns for people living with MS by integrating mental health into the standard clinical interview for MS patients. Healthcare providers (HCPs) may also utilize screening tools to monitor mental health status and refer patients to a mental health specialist when appropriate. We review wellness- and mindfulness-based interventions and highlight the ability of these techniques to improve wellbeing and QoL. For example, digital/virtual opportunities for care and social support during the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly becoming more available and can continue to serve as an important tool in the future. By promoting an open dialogue between people living with MS and their care teams, a comprehensive approach to MS care which incorporates mental health can be achieved. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Prevalence, Etiology, and Clinical Course Implications of Mental Health Concerns for People Living with MS

How Common are Mental Health Concerns for People Living with MS and How Do They Manifest?

Research on the prevalence of mental health disorders reports variable data, in part due to the study population, study size, or type of screening test used. While prevalence rates may vary between studies, it is generally accepted that mood and mental health disorders may be more likely for people living with MS than for the general population [7, 8, 17]. In Table 1, we reference approximate prevalence rates and signs/symptoms for each mental health disorder discussed and share patient perspectives with the objective to familiarize the MS care team with the language patients may use to convey their experience.

A common thread in the experiences of people living with MS is heightened levels of stress, which can exacerbate/contribute to the development of physical and mental health concerns. Relative to the general population, people living with MS may experience heightened levels of stress due to situations including, but not limited to, the sudden change to one’s life upon diagnosis, the unpredictability of MS, experiencing invisible symptoms such as cognitive impairment, managing newly visible symptoms, financial complications, feeling loss of control, and navigating unexpected decisions [18, 19]. Effective stress management is essential for people living with MS, as stress/stressful life events have been linked to both the onset of MS and exacerbating disease progression/relapses [20,21,22]. Major negative stressful events (e.g., assault, hospitalization) have been shown to be correlated with an increased risk of new lesions, while positive stressful events (e.g., weddings, moving to a nicer home) may predict a decreased risk [23]. Unmitigated heightened and/or chronic stress can influence the development of other emotional changes and therefore warrants attention from HCPs [24].

Depression is one of the most common emotional changes experienced while living with MS and one of the strongest factors causing reduced QoL [25,26,27,28,29,30]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature on the prevalence of depression and anxiety in MS, the prevalence of depression was 30.5% and 22.1% for anxiety in a total sample size of 87,756 people living with MS [31] (Table 1). Depression can range from occasional, mild depressive symptoms to persistent, more severe clinical depression; symptoms of depression are shown in Table 1, and these can vary in severity [25, 31]. Depression is associated with anxiety, which can independently have a negative influence on patient QoL [32, 33]. As shown in Table 1, anxiety can manifest with some combination of both physiological and psychological symptoms [34]. Anxiety is associated with increased suicidal ideation; it has been suggested that attempted suicide and completed suicide both occur at rates twice as high as in the general population for people living with MS [35,36,37]. Living alone, social isolation, having a mental health condition, and/or experiencing high levels of stress may also contribute to this suicidal ideation risk [38]. Additionally, people living with MS may develop adjustment disorder, wherein emotional changes occur within 1–3 months of a stressful event (e.g., an MS diagnosis) because of a maladaptive response to the event [39, 40] (Table 1).

While less common than depression, anxiety, and their associated concerns, people living with MS may have a heightened risk of bipolar disorder relative to the general population [9, 41]. An increase in the prevalence of psychosis/psychotic disorders for people living with MS has also been reported [7] (Table 1).

What Causes Mental Health Disorders in MS?

The etiology of mental health disorders and emotional changes is complex and multifactorial, and could be due to a combination of challenges of living with MS or symptoms of the disease.

Lesions in multiple brain regions have been implicated in causing mental health disorders for people living with MS; the current understanding of neurobiological risk factors (i.e., lesion location, endocrine systems, and medications) was recently reviewed by Silveira et al. [8]. Mood changes can also be influenced by neuroinflammation, with even subclinical neuroinflammation predicting psychological change [50]. Physical symptoms of MS and other invisible symptoms, medication side effects, genetic predisposition, and life events can all influence the likelihood of developing a mental health disorder [8]. Both biological and social factors can contribute to depression and anxiety [32]. Furthermore, having one mental health disorder can put a patient at risk for another, for example, having depression puts patients at higher risk for anxiety [33]. In addition to these factors, the interplay of invisible symptoms and perceived stigma endured by people living with MS, described in our companion review [4], also may impact mental health burdens. How a person living with MS feels can be a combination of reacting to the challenges of living with a long-term, unpredictable disease and symptoms of the disease and can even lead to feelings of grief in people living with MS [24, 51].

How Can Mental Health Change over Time for a Person Living With MS?

Mental health for a person with MS may change over the course of their lifetime, from the time of their initial diagnosis and throughout their adjustments to living with MS (Fig. 1). A decline in mental health has been associated with receipt of the MS diagnosis [52]. Receiving the diagnosis of MS causes uncertainty for patients as they are likely unfamiliar with MS and how it will impact their life (Fig. 1). Generally, worsened mental health is associated with high feelings of uncertainty rather than MS disease severity [32]. While living with MS, individuals will observe their abilities change, which is likely to negatively influence their mood (Fig. 1). People living with MS may experience complex feelings, such as thoughts that life for their caregivers would be better without them and increasing depression as their perceived disabilities worsen over time [53]. People living with MS may experience having to cope with loss of physical and mental abilities, dealing with new relationship dynamics, and adapting to a different lifestyle than the one they envisioned [24]. Living with MS also may involve a great deal of uncertainty, which plays a large part in the development of mental health concerns. For example, patients must bear the emotional weight of fear of disease progression, reactions to physical and QoL changes, as well as side effects of medications [54, 55]. As people living with MS adjust to living with the disease, their mental well-being may improve as they learn more about MS and adopt techniques for managing the symptoms, stigma/psychosocial influences, and mental health concerns which may occur due to MS [56, 57]. With time and a strong support system, a person living with MS can utilize many strategies to enrich their life and thrive despite having MS (Fig. 1).

How Can We as a Community Address Mental Health in a Comprehensive Manner?

Normalize Discussions of Mental Health at Routine MS Care Visits

Every person living with MS will have a unique mental health experience, although there are common themes which HCPs should convey as normal components of living with MS, such as the adjustments to changing abilities discussed in Fig. 1 and the ‘burden of choice’ regarding disclosure of MS to peers/employers [4]. Mental health intervention may be offered at the time of diagnosis as this moment marks a dramatic change for the patient. At diagnosis and in subsequent visits, during the clinical interview HCPs may listen carefully to patients’ descriptions of concerns, life events, and their emotions surrounding them. By regularly considering emotional well-being as seriously as physical well-being, HCPs can normalize conversations about mental health and offer appropriate resources.

HCPs can supplement a thorough clinical interview with screening tools, which serve to both aid in open communication and identify/monitor mental health changes. In Table 2, we outline common screening tools that we suggest HCPs may utilize for routine screening and timely management of mental health concerns. We further indicate usage notes from our clinical experience, such as noting when tools are brief to administer, which can allow for ease of implementation despite time constraints (Table 2). At minimum, a visit should incorporate depression/anxiety screening tools [e.g., the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and 7-Item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)], an update of life events, and discussion of any disease management changes. Answers to depression/anxiety screening tools can serve as a starting point to initiate open communication/discussion by informing follow-up questions specific to the patient’s responses. HCPs should also ask patients if they have the social supports and other resources they need to meet their concerns, as stress can occur when there is a shortage of resources in comparison to one’s needs. At every visit, any negative/distressing life events that have occurred should be monitored; this is always important, but especially so within the first 3 months after receiving the MS diagnosis when adjustment disorder is a risk. Any past suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempts should be discussed at every interaction, as these are the most informative predictors of future attempts [58]. For bipolar disorder, a thorough clinical interview which educates about mania/bipolar disorder symptoms and takes a strong family history is recommended. Following an interview in which mania/bipolar disorder is suspected, the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) may be utilized to help clarify the symptoms a person living with MS may be experiencing (Table 2).

Utilize Supports from Personal Networks and Extended Resources

In addition to the steps that HCPs can take to normalize mental health discussed in the previous section, people living with MS can self-manage aspects of mental health by educating themselves, seeking out appropriate supports and resources, and asking for help by talking openly with their care team. The mental health needs and stress caused by living with invisible symptoms vary between individual patients, as each person with MS will have a unique set of life experiences, coping strategies, and thought processes. These factors can contribute to psychological resilience or the individual’s ability to mitigate the negative effects of stress and overcome adversity [75, 76]. Resiliency building is an important component of patient-driven care, as higher resilience may reduce the risk of psychiatric symptoms and maintain QoL in people living with MS [77].

A vital aspect of resiliency building is maintaining social connections, as social support that a patient may or may not receive from their community is another contributing factor to mental health [78, 79]. Coupled with professional support when needed, social support (coming from significant others, family members, close friends, neighbors, worship community, etc.) may help individuals navigate the uncertainties of living with MS by maintaining some continuity in their social identity [80]. Strong social support may predict reduced depression symptoms, lower anxiety symptoms, and better mental health overall in people living with MS, mediated by increased resilience [81]. Being able to contribute to society by maintaining a career or volunteering can help people living with MS find meaning and purpose in their lives, which is crucial for resiliency [79].

“When I was asked to be a member of the Research Committee for iConquerMS, I found a new appreciation for me, my knowledge, and the skills I brought to the table. No one had seen that value or asked to use those talents in years, and it had a HUGE impact on my mental health and improved sense of self.

–Cherie Binns

The value of community support is highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, as with the reduced ability to gather in groups, many people living with MS find their mental health worsens. Social interactions are influenced not only by the need to stay physically isolated during peak virus outbreaks, but also by the limitations of communicating while wearing a mask/face covering in public [82]. Masks limit nonverbal communication between individuals, thus, when people living with MS attempt various activities in their communities, they may now experience additional mental health symptoms when failing to find nonverbal positive validation in their environment (e.g., inability to tell if someone else is smiling behind a mask). Masks have also changed verbal expression, as attempts to communicate through masks or glass dividers may result in raised voices, repeated attempts to express oneself, and/or erroneous transactions. These added frustrations may further decrease the desire of a person living with MS to engage in society.

“COVID-19 has allowed me to justify my depressive behaviors, like isolation, because of the concerns around going out. I also have to stay away from news outlets or social media. In my decreased mental state, the repetition of information about COVID-19 increases my worries over what is to come.”

–Keisha Currie

In the absence of adequate social support, people living with MS can build an understanding community through a variety of in-person and online support groups, hosted by MS societies and/or patient groups [83, 84]. For example, the National MS Society ‘Find Support’ page [85] offers multiple options to connect with others, including the MSFriends® helpline which people living with MS or their family members can call to connect with a volunteer living with MS [86]. Likewise, MultipleSclerosis.net has a ‘Community’ where registered users can access forums to communicate with other people living with MS [87]. People living with MS can also find a multitude of support groups on Facebook and Instagram, often affiliated with societies such as the National MS Society [88], the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America [89], and the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation [90]. Virtual support groups hosted on social media platforms feature varying levels of privacy and support, including fully public communities, private groups to which individuals may request access, and invitation-only groups; people living with MS may identify which type(s) fit their individual privacy concerns and support needs by seeking recommendations from trusted peers and HCPs [91, 92]. These virtual support groups offer many benefits to people living with MS, including the opportunity to normalize their physical and emotional experiences and learn more about MS care in an accessible manner [84]. Some people living with MS may require encouragement to continue participating in social groups, as they may become more socially isolated as disease progresses [93]. Patients who are not made aware of support group options or choose not to participate may suffer through their mental health concerns on their own and eventually resort to self-referral to a mental health specialist only after many years and/or a stressful life event [94].

Encourage Holistic Management Techniques and Interdisciplinary Care

We propose that with a patient-centered interdisciplinary approach, visualized in Fig. 2, HCPs can and should include discussions of mental health and resources for building resilience into routine MS care (Fig. 2). Patients report that their mental health care is made easier by having their mental health and MS specialists on the same site, where communication between team members is simplified and medical records are shared [94]. In the absence of an integrative infrastructure neurologists may instead make referrals to external mental health providers, which may include psychologists, psychiatrists, marriage and family therapists, and/or social workers. Neurologists may base their referral decisions on patient screening tool(s) scores, clinical interview, mental health history, and medication history.

An interdisciplinary care model supports an individual with MS by combining a variety of care and resources. Care from interdisciplinary medical professionals ensures that all physical and mental health concerns can be managed. Mindfulness-based interventions can be tailored to a person living with MS’s individual tastes and abilities. An understanding personal network (e.g., family, friends, colleagues, fellow members of support groups) can contribute to resilience. People living with MS can also build extended communities via peers, MS societies, and patient advocacy groups

Even if not on the same site, interdisciplinary care that brings together behavioral medicine and standard MS care practices allows HCPs to understand multiple facets of their patient’s health and positions them to offer optimal personalized clinical care [95, 96]. This approach can be informed by a deliberative care model, in which HCPs engage people living with MS in a dialogue about how they feel and make shared decisions regarding steps to promote emotional well-being [97, 98]. When patients are listened to and included in the shared decision-making process, they may feel more confident about their care and have better relationships with their providers [6, 99]. Therefore, a personalized combination of interdisciplinary management options can provide the best likelihood of meeting a patient’s mental health needs.

The foundation for a comprehensive approach to care includes an annual primary care visit to address aspects of general health which can contribute to mental health (e.g., vitamin D deficiency, smoking, sleep, alcohol use, exercise, and diet) and a neurologist who asks about general health during MS disease assessment [95, 96, 100, 101] (Fig. 2). During the neurologist and primary care visits, active listening by HCPs to both patients and their significant others, as applicable, will be an important part of initial assessment of mental health. As previously discussed, HCPs can supplement a robust clinical interview with appropriate screening tools (Table 2) and referrals to other specialists as needed. This approach allows for HCPs to better understand the type of support the individual requires and offer appropriate resources, such as patient-driven self-management techniques for mental health. One such technique that has gained increasing support in recent years is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a type of psychotherapy which focuses on improving thought and behavioral patterns. CBT typically involves teaching people living with MS techniques such as self-monitoring of daily stress, cognitive restructuring, and problem-solving strategies and may be effective for reduction of stress and depression/anxiety symptoms and improvements in QoL [102]. A randomized controlled trial suggested that a CBT-based stress-management therapy program administered for 24 weeks reduced the number of new brain lesions during the 24-week treatment period [103]; however, the effect of the CBT-based therapy diminishes once the treatment period is over, suggesting that sustained CBT may be required for long-term benefit [103].

In addition to such guidance from medical practitioners, group-based supports have an important role in increasing resilience and psychosocial reserve, which is a composite of measures assessing participants' feelings of belonging, social support, and sense of control [104]. As discussed in the previous section, people living with MS can obtain social supports through their personal networks, extended resources, or group therapy (Fig. 2), where patients find comfort in the fact that they are not alone in their mental health journey [105,106,107]. Medical care and social supports can be incorporated together at shared medical appointments, which show the capacity to improve both physical and psychological outcomes [108]. In a study of group-based CBT that involved six groups of patients during four consecutive sessions and a 6-month follow-up, patients were initially resistant, but increasingly became open to change during intervention [109]. The group-based CBT, which promoted identity redefinition and self-efficacy, allowed the participants to understand how the changes in their lives were not unusual when placed in the context of a group of peers.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBI), such as meditation, yoga, and/or music therapy, can also support robust mental health and are a useful tool for people living with MS who do not wish to be on pharmacologic management [100, 110,111,112,113] (Fig. 2). Indeed, some patients have shown greater interest in holistic, mindfulness-based approaches relative to pharmacotherapy [113, 114]. Exercise may help to improve the satisfaction of people living with MS with their physical, mental, and social functioning [115] and may have positive impacts on mood and reduce inflammation [100, 116, 117]. Practices that incorporate gratitude can also improve emotional well-being [118]. In addition to mental health benefits, these MBIs may also help in managing other symptoms of MS such as pain and fatigue [119, 120]. Furthermore, the variety of available non-pharmacological MBIs allows for patient-motivated choices about which type to utilize based on their preferences and ability.

Pharmacotherapy options may also be considered for mood and mental health disorders to supplement the aforementioned wellness-based strategies. While many pharmacotherapy options are similar to recommendations for the general population, HCPs will need to consider drug-drug interactions with disease-modifying therapies for MS and how side effects might exacerbate MS symptoms. For some common mood/anxiety symptoms, neurologists themselves may be able to prescribe appropriate pharmacotherapy (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors); however, for less common mental health conditions referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist may be needed. Pharmacotherapy options for mood and neuropsychiatric disorders in people living with MS have previously been expertly reviewed [7, 40]. These treatment options are an important tool and can be greatly beneficial for individuals for whom wellness-based care alone is insufficient to maintain QoL.

Accessibility of these various care options is an important consideration, and the pandemic has underscored the utility of telehealth for primary care, neurologist appointments, and mental health care, virtual exercise and support groups, and digital mood tracking resources. Telehealth options for individual/group therapy are becoming more widely available, in part precipitated by the pandemic, and offer an opportunity for individuals with lack of transportation support to benefit from more regular care [121, 122]. Home-based MBI and exercise programs can support psychological and QoL improvements [123]. Similarly, innovations such as digital/virtual tools for mood tracking likewise support people living with MS as they self-manage their care [124, 125]. People living with MS may benefit from digital tools and apps developed for both the general population as well as MS patients, which we summarize in Table 3. These options are continually evolving to better meet the needs of people living with MS, presenting care teams with an opportunity to reinvent models of care to include a hybrid of physical and digital options [126, 127].

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Mental health disorders present a significant challenge for people living with MS. However, as with other invisible symptoms, the connection between mental health disorders and MS is frequently underappreciated. Given this, it is imperative to proactively ask patients about their mental health status as part of routine MS care. Routinely assessing how patients feel may allow HCPs to detect trends in patient mood or significant changes since the last visit. In these cases, HCPs can inquire more about resources the patient may need, administer screening tools, or make a referral to a specialist if needed. It is advisable to offer the referral when a person with MS is screened for mental illness; however, cost may be an issue for some patients. Referral to a specialist will be necessary when lifestyle adjustments and/or initiation of pharmacotherapy is not effective. By normalizing conversations around mental health and implementing appropriate management strategies, HCPs can empower people living with MS to navigate the stressors and uncertainties of living with MS while maintaining their QoL.

An interdisciplinary approach can optimize the communication between various players in a patient’s care team. Even if not formally affiliated with one another, neurologists should work together with a patient’s mental health specialist(s) and the person living with MS themselves to ensure physical and psychological needs are met. Interdisciplinary care teams that normalize management of mental health, promote resiliency-building, and encourage HCPs and people living with MS to learn together are the future of MS care.

This future also embraces technology that supports emotional well-being. Social media has drastically changed information dissemination from MS societies and connectivity between the patient and their peers with MS. These social media platforms have become a source of social support for many individuals. Technology also affords the opportunity to provide 24/7 mental health care, which can be crucial for people living with MS who may be suffering from mental health disorders such as severe depression or anxiety. Telehealth has been propelled to the forefront of patient care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and for a patient population in which mobility can be a concern, it will likely remain an important tool moving forward. Developing secure, user-friendly technological advancements for screening, monitoring, and managing mental health concerns could ease the documentation and sharing of a patient’s experience between members of the MS care team. Promoting a dialogue around mental health concerns, integrating mental health specialists into an MS care team, and making use of digital innovations, taken together, have great potential to positively influence patient care.

References

National MS Society. MS symptoms 2020. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Parker LS, Topcu G, De Boos D, das Nair R. The notion of “invisibility” in people’s experiences of the symptoms of multiple sclerosis: a systematic meta-synthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020:1–15.

White CP, White MB, Russell CS. Invisible and visible symptoms of multiple sclerosis: which are more predictive of health distress? J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40(2):85–95 (102).

Lakin L, Davis BE, Binns CC, Currie KM, Rensel MR. Comprehensive approach to management of multiple sclerosis: addressing invisible symptoms—a narrative review. Neurol Ther. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00239-2.

American Academy of Neurology, Members MSWG. Multiple sclerosis quality measurement set: American Academy of Neurology; 2015. https://www.aan.com/siteassets/home-page/policy-and-guidelines/quality/quality-measures/14msmeasureset_pg.pdf. Accessed 23 Sept 2020.

Rieckmann P, Centonze D, Elovaara I, Giovannoni G, Havrdová E, Kesselring J, et al. Unmet needs, burden of treatment, and patient engagement in multiple sclerosis: a combined perspective from the MS in the 21st century Steering Group. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:153–60.

Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, McDonald C, Calabresi PA, Ahmed MA, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697–708.

Silveira C, Guedes R, Maia D, Curral R, Coelho R. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of multiple sclerosis: state of the art. Psychiatry Investig. 2019;16(12):877–88.

Jun-O’Connell AH, Butala A, Morales IB, Henninger N, Deligiannidis KM, Byatt N, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorders and association with quality of life in a cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;29(1):45–51.

Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(9):556–66.

Gill S, Santo J, Blair M, Morrow SA. Depressive symptoms are associated with more negative functional outcomes than anxiety symptoms in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;31(1):37–42.

McKay KA, Tremlett H, Fisk JD, Zhang T, Patten SB, Kastrukoff L, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018;90(15):e1316–23.

Mohr DC, Hart SL, Fonareva I, Tasch ES. Treatment of depression for patients with multiple sclerosis in neurology clinics. Mult Scler J. 2006;12(2):204–8.

Raissi A, Bulloch AGM, Fiest KM, McDonald K, Jetté N, Patten SB. Exploration of undertreatment and patterns of treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(6):292–300.

Binns CC. Bridge over troubled waters. MS FOCUS Mag. 2020;13:2020.

Stojanov A, Malobabic M, Milosevic V, Stojanov J, Vojinovic S, Stanojevic G, et al. Psychological status of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis during coronavirus disease-2019 outbreak. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;45:102407.

Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Tremlett H, Wolfson C, Warren S, Tennakoon A, et al. Differences in the burden of psychiatric comorbidity in MS vs the general population. Neurology. 2015;85(22):1972–9.

Ross A, Weigel M. What is the role of stress in multiple sclerosis? Couns Points. 2016;11(2):4–12.

Foley F, Sarnoff J. Taming stress in multiple sclerosis [Brochure]. 2016. Retreived from: National MS Society. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Brochure-Taming-Stress.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Cox D, Pelletier D. Association between stressful life events and exacerbation in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2004;328(7442):731.

Mohr DC, Pelletier D. A temporal framework for understanding the effects of stressful life events on inflammation in patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20(1):27–36.

Briones-Buixassa L, Milà R, Ma Aragonès J, Bufill E, Olaya B, Arrufat FX. Stress and multiple sclerosis: a systematic review considering potential moderating and mediating factors and methods of assessing stress. Health Psychol Open. 2015;2(2):2055102915612271.

Burns MN, Nawacki E, Kwasny MJ, Pelletier D, Mohr DC. Do positive or negative stressful events predict the development of new brain lesions in people with multiple sclerosis? Psychol Med. 2014;44(2):349–59.

National MS Society. Emotional changes 2020. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms/Emotional-Changes. Accessed 20 Aug 2020.

National MS Society. Depression 2020 [updated 2020]. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms/Depression. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Fruehwald S, Loeffler-Stastka H, Eher R, Saletu B, Baumhackl U. Depression and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104(5):257–61.

D’Alisa S, Miscio G, Baudo S, Simone A, Tesio L, Mauro A. Depression is the main determinant of quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a classification-regression (CART) study. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(5):307–14.

Yalachkov Y, Soydas D, Bergmann J, Frisch S, Behrens M, Foerch C, et al. Determinants of quality of life in relapsing-remitting and progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:33–7.

Schmidt S, Jostingmeyer P. Depression, fatigue and disability are independently associated with quality of life in patients with multiple Sclerosis: results of a cross-sectional study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;35:262–9.

Berrigan LI, Fisk JD, Patten SB, Tremlett H, Wolfson C, Warren S, et al. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: direct and indirect effects of comorbidity. Neurology. 2016;86(15):1417–24.

Boeschoten RE, Braamse AMJ, Beekman ATF, Cuijpers P, van Oppen P, Dekker J, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:331–41.

Hanna M, Strober LB. Anxiety and depression in multiple sclerosis (MS): antecedents, consequences, and differential impact on well-being and quality of life. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;44:102261.

Pham T, Jetté N, Bulloch AGM, Burton JM, Wiebe S, Patten SB. The prevalence of anxiety and associated factors in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:35–9.

Franco M. Anxiety Multiple Sclerosis Association of America 2014. https://www.mymsaa.org/ms-information/symptoms/anxiety/. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Brenner P, Burkill S, Jokinen J, Hillert J, Bahmanyar S, Montgomery S. Multiple sclerosis and risk of attempted and completed suicide—a cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(8):1329–36.

Feinstein A, Pavisian B. Multiple sclerosis and suicide. Mult Scler. 2017;23(7):923–7.

Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, Koutsis G, Papadimitriou GN. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14–21.

Feinstein A. An examination of suicidal intent in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2002;59(5):674–8.

O’Donnell ML, Agathos JA, Metcalf O, Gibson K, Lau W. Adjustment disorder: current developments and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2537.

Pérez LP, González RS, Lázaro EB. Treatment of mood disorders in multiple sclerosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2015;17(1):323.

Meier U-C, Ramagopalan SV, Goldacre MJ, Goldacre R. Risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in patients with multiple sclerosis: record-linkage studies. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:662.

Cirino E. Adjustment Disorder healthline: healthline; 2019. https://www.healthline.com/health/adjustment-disorder. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Minden SL, Feinstein A, Kalb RC, Miller D, Mohr DC, Patten SB, et al. Evidence-based guideline: assessment and management of psychiatric disorders in individuals with MS: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(2):174–81.

The National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar Disorder: The National Institute of Mental Health; 2020. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml#part_145404. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Satzer D, Bond DJ. Mania secondary to focal brain lesions: implications for understanding the functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(3):205–20.

Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, Stuve O, Trojano M, Sorensen PS, et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21(3):305–17.

NHS. Psychosis 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/psychosis/symptoms/. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Dolce K. I found out the hard way which of my drugs interact badly with each other. Multiplesclerosis.net. 2020. Retrieved from: https://multiplesclerosis.net/living-with-ms/hard-way-drugs-interact/. Accessed 29 Sept 2020.

Boster A. Rare and unusual MS symptoms (I've seen in clinic); 2018.

Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, Polidoro S, Perugini J, Macchiarulo G, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338–47.

Moghadasi AN. “Disability Grief”: a patient’s allegorical expression of her disability. Iran J Neurol. 2019;18(4):190–1.

Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, van der Meche FG, Passchier J, Hintzen RQ. Impact of recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis on quality of life, anxiety, depression and distress of patients and partners. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108(6):389–95.

Binns C. Suicide and MS. MSFOCUS Mag. 2020;22:32.

Burtchell J, Fetty K, Miller K, Minden K, Kantor D. Two sides to every story: perspectives from four patients and a healthcare professional on multiple sclerosis disease progression. Neurol Ther. 2019;8(2):185–205.

Tintoré M, Alexander M, Costello K, Duddy M, Jones DE, Law N, et al. The state of multiple sclerosis: current insight into the patient/health care provider relationship, treatment challenges, and satisfaction. Patient Prefer Adher. 2017;11:33–45.

Spencer LA, Silverman AM, Cook JE. Adapting to multiple sclerosis stigma across the life span. Int J MS Care. 2019;21(5):227–34.

Irvine H, Davidson C, Hoy K, Lowe-Strong A. Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis: exploration of identity redefinition. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(8):599–606.

Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094–100.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–44.

Pfizer. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) screeners 2013. http://www.phqscreeners.com. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Pearson. Beck Depression Inventory-II (pricing and ordering) 2020. https://www.pearsonassessments.com/store/usassessments/en/Store/Professional-Assessments/Personality-%26-Biopsychosocial/Beck-Depression-Inventory-II/p/100000159.html?tab=pricing-ordering. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Terrill AL, Hartoonian N, Beier M, Salem R, Alschuler KN. The 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale as a tool for measuring generalized anxiety in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(2):49–56.

Litster B, Fiest KM, Patten SB, Fisk JD, Walker JR, Graff LA, et al. Screening tools for anxiety in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Int J MS Care. 2016;18(6):273–81.

Mapi Research Trust. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) 2020. https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/hospital-anxiety-and-depression-scale#need_this_questionnaire. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Lorenz L, Bachem RC, Maercker A. The adjustment disorder-new module 20 as a screening instrument: cluster analysis and cut-off values. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2016;7(4):215–20.

Einsle F, Köllner V, Dannemann S, Maercker A. Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(5):584–95.

Ben-Ezra M, Mahat-Shamir M, Lorenz L, Lavenda O, Maercker A. Screening of adjustment disorder: scale based on the ICD-11 and the adjustment disorder new module. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:91–6.

Lorenz L. Self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorder ADNM—20 questionnaire: University of Zurich; 2016. https://www.psychology.uzh.ch/dam/jcr:15220404-d1b2-4d9a-9661-f1709b4ca3f4/ADNM_20.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

Hirschfeld RM. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a simple, patient-rated screening instrument for bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(1):9–11.

Phalen PL, Rouhakhtar PR, Millman ZB, Thompson E, DeVylder J, Mittal V, et al. Validity of a two-item screen for early psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:861–8.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92.

NovoPsych. Brief-COPE 2020. https://novopsych.com.au/assessments/brief-cope/. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1(2):165–78.

Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12–23.

Nakazawa K, Noda T, Ichikura K, Okamoto T, Takahashi Y, Yamamura T, et al. Resilience and depression/anxiety symptoms in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;25:309–15.

Godman H. How resilience training can help people with MS. US News and World Report. 2017.

National MS Society. Resilience: addressing the challenges of MS. 2020. https://multiplesclerosis.net/living-with-ms/hard-way-drugs-interact/. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Barker AB, Lincoln NB, Hunt N, das Nair R, . Social identity in people with multiple sclerosis: an examination of family identity and mood. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(2):85–91.

Koelmel E, Hughes AJ, Alschuler KN, Ehde DM. Resilience mediates the longitudinal relationships between social support and mental health outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(6):1139–48.

Ong S. How face masks affect our communication. BBC Future. 2020. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200609-how-face-masks-affect-our-communication. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Holland K. Online Multiple Sclerosis Support Groups: Healthline; 2018. https://www.healthline.com/health/multiple-sclerosis/support-groups. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Kantor D, Bright JR, Burtchell J. Perspectives from the patient and the healthcare professional in multiple sclerosis: social media and patient education. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(1):23–36.

National MS Society. Find support 2020. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Resources-Support/Find-Support. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

National MS Society. MSFriends 2020. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Programs-and-Services/Programs/MSFriends. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

MultipleSclerosis.net. Community 2020. https://www.multiplesclerosis.net/community/. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

National MS Society. National Multiple Sclerosis Society Community [private Facebook group] 2020. https://www.facebook.com/groups/1119529838249750/. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Multiple Sclerosis Association of America. Multiple Sclerosis Association of America [community tab of organization Facebook page] 2020. https://www.facebook.com/msassociation/community/?ref=page_internal. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. Multiple Sclerosis Foundation Facebook Group 2020. https://www.facebook.com/groups/msfocus. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. Multiple Sclerosis Foundation [public Facebook group] 2020. https://www.facebook.com/groups/msfocus/. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. MS Focus Confidential [private Facebook group] 2020. https://www.facebook.com/groups/906460479752961/. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Lorefice L, Fenu G, Frau J, Coghe G, Marrosu MG, Cocco E. The burden of multiple sclerosis and patients’ coping strategies. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8(1):38–40.

Rintell DJ, Frankel D, Minden SL, Glanz BI. Patients’ perspectives on quality of mental health care for people with MS. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(6):604–10.

Sullivan A. The importance of interdisciplinary care in MS. In: Meglio M, editor. NeurologyLive; 2020. https://www.neurologylive.com/conferences/cmsc-2020/the-importance-of-interdisciplinary-care-in-ms. Accessed 12 July 2020.

Sullivan A. Science, art, and practice of behavioral medicine in MS: 2020 CMSC virtual annual meeting; 2020.

Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267(16):2221–6.

Strum J. Bonus: From the CMSC Meeting Day 1 [Internet]; 2019 May 29, 2019 [cited August 25, 2020]. Podcast. https://www.realtalkms.com/bonus-from-the-cmsc-meeting-day-1-5-29-2019/. Accessed 25 Aug 2020.

Methley A, Campbell S, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Chew-Graham C. Meeting the mental health needs of people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study of patients and professionals. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(11):1097–105.

Rensel MR, Hersch C, Moss B. General health and wellness in multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders: clinical guide to diagnosis, medical management, and rehabilitation. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2018. p. 235–52.

Rensel MR. General health and wellness in multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders: diagnosis, medical management, and rehabilitation. 1st ed. New York: Demos Medical Publishing, LLc.; 2013. p. 235–42.

Reynard AK, Sullivan AB, Rae-Grant A. A systematic review of stress-management interventions for multiple sclerosis patients. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(3):140–4.

Mohr DC, Lovera J, Brown T, Cohen B, Neylan T, Henry R, et al. A randomized trial of stress management for the prevention of new brain lesions in MS. Neurology. 2012;79(5):412–9.

Cadden MH, Arnett PA, Tyry TM, Cook JE. Judgment hurts: the psychological consequences of experiencing stigma in multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2018;208:158–64.

Robati Z, Shareh H. The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral group therapy in anxiety and self-esteem in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Fundam Ment Health. 2018;20(6):405–16.

Hoseini Tabatabaei R, Bolghan-Abadi M. Effectiveness of solution-focused group therapy in generalized anxiety disorder in patients with multiple sclerosis. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2020;22(2):e69355.

Giovannetti AM, Quintas R, Tramacere I, Giordano A, Confalonieri P, Messmer Uccelli M, et al. A resilience group training program for people with multiple sclerosis: results of a pilot single-blind randomized controlled trial and nested qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231380.

Abbatemarco JR, Cohen JA, Udeh BL, Rensel MR, editors. Improved multiple sclerosis management using shared medical appointments—a single center experience. Madison: ACTRIMS; 2020.

Borghi M, Bonino S, Graziano F, Calandri E. Exploring change in a group-based psychological intervention for multiple sclerosis patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(14):1671–8.

Russell RD, Black LJ, Pham NM, Begley A. The effectiveness of emotional wellness programs on mental health outcomes for adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;44:102171.

Simpson R, Simpson S, Ramparsad N, Lawrence M, Booth J, Mercer SW. Mindfulness-based interventions for mental well-being among people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(9):1051–8.

Impellizzeri F, Leonardi S, Latella D, Maggio MG, Foti Cuzzola M, Russo M, et al. An integrative cognitive rehabilitation using neurologic music therapy in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(4):e18866.

Motl RW, Mowry EM, Ehde DM, LaRocca NG, Smith KE, Costello K, et al. Wellness and multiple sclerosis: The National MS Society establishes a Wellness Research Working Group and research priorities. Mult Scler. 2018;24(3):262–7.

Dunn M, Bhargava P, Kalb R. Your patients with multiple sclerosis have set wellness as a high priority-and the national multiple sclerosis society is responding. US Neurol. 2015;11(2):80–6.

Alphonsus KB, Su Y, D’Arcy C. The effect of exercise, yoga and physiotherapy on the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;43:188–95.

Donia SA, Allison DJ, Gammage KL, Ditor DS. The effects of acute aerobic exercise on mood and inflammation in individuals with multiple sclerosis and incomplete spinal cord injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2019;45(1):117–24.

Hasanpour DA. Influence of yoga and aerobics exercise on fatigue, pain and psychosocial status in patients with multiple sclerosis: a randomized trial. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2016;56(11):1417–22.

Crouch TA, Verdi EK, Erickson TM. Gratitude is positively associated with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2020;65(3):231–8.

Senders A, Borgatti A, Hanes D, Shinto L. Association between pain and mindfulness in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional survey. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(1):28–34.

Simpson R, Simpson S, Ramparsad N, Lawrence M, Booth J, Mercer SW. Effects of Mindfulness-based interventions on physical symptoms in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;38:101493.

Gandy M, Karin E, McDonald S, Meares S, Scott AJ, Titov N, et al. A feasibility trial of an internet-delivered psychological intervention to manage mental health and functional outcomes in neurological disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136:110173.

Sullivan AB, Kane A, Roth AJ, Davis BE, Drerup ML, Heinberg LJ. The COVID-19 crisis: a mental health perspective and response using telemedicine. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:2374373520922747.

Grubic Kezele T, Babic M, Stimac D. Exploring the feasibility of a mild and short 4-week combined upper limb and breathing exercise program as a possible home base program to decrease fatigue and improve quality of life in ambulatory and non-ambulatory multiple sclerosis individuals. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(4):733–43.

Lukmanji S, Pham T, Blaikie L, Clark C, Jetté N, Wiebe S, et al. Online tools for individuals with depression and neurologic conditions: a scoping review. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7(4):344–53.

Morin A. The 7 Best Mental Health Apps of 2020: verywellmind; 2020. https://www.verywellmind.com/best-mental-health-apps-4692902. Accessed 25 Sept 2020.

Olayiwola JN, Magaña C, Harmon A, Nair S, Esposito E, Harsh C, et al. Telehealth as a bright spot of the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from the virtual frontlines (“Frontweb”). JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19045.

Henry TA. COVID-19 makes telemedicine mainstream. Will it stay that way? AMA. 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/covid-19-makes-telemedicine-mainstream-will-it-stay-way. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Overcoming Multiple Sclerosis. Overcoming multiple sclerosis 2020. https://overcomingms.org/. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

MyLife. Find your quiet place with MyLife 2020. https://my.life/. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Headspace. Headspace 2020. https://www.headspace.com/.

Moodfit. Moodfit: fitness for your mental health 2020. https://www.getmoodfit.com/.

Society NM. Happy the App 2020. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Resources-Support/Find-Support/Happy-the-App.

Happify Health. About us 2020. https://happify.com/health/about/. Accessed 24 Sept 2020.

Marques LJ. Partnership aims for FDA-approved app that aids mental health in MS, Sanofi announces. Mult Scler News Today. 2019;23:2019.

Acknowledgements

Our provider authors wish to thank their patients for all they have taught them about living with multiple sclerosis. Dr. Davis wishes to thank his mentor, Dr. Amy Sullivan, who inspires him and exemplifies a level of care that breaks barriers, reduces stigma, and paves the way for others. Keisha Currie would like to thank her healthcare team and the Sumter MS Warriors Support Group.

Funding

The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. No funding was provided for the authoring of this review. The authors received no honoraria related to the development of this publication.

Medical Writing

Medical writing support was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. This medical writing support, including assisting authors with the development of the manuscript drafts and incorporation of comments, was provided by Meredith Whitaker, PhD, of Alphabet Health (New York, NY), according to Good Publication Practice guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript concept/design, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript drafts, and provided final approval of the manuscript and enhanced content as submitted.

Disclosures

Lynsey Lakin has received funding from serving as a consultant and participating on advisory boards and Speaker Bureaus for the following Pharmaceutical companies: Alexion, Allergan, Biogen, Novartis, EMD Serono, Sanofi Genzyme, Genentech, Teva, and Viola Bio Pharmaceutical Companies as well as for Can Do MS and International Organization of MS Centers non-profit organization. She has also received grant funds from Abbvie Pharmaceuticals. Bryan E Davis has consulted for Novartis. Bryan E Davis is now affiliated with the Norton Neuroscience Institute, Norton Healthcare, 3991 Dutchmans Lane, Suite 310, Louisville, KY 40207, USA. Cherie C Binns has consulted for Novartis and is a contributor to MS Focus magazine. Keisha Currie has consulted for Novartis. Mary R Rensel has served on advisory boards/panels for Serono and Biogen; consulted for Biogen, Teva, Genzyme, and Novartis; received commercial research support from Medimmune and Genentech; received foundation/society research support from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society; received educational grants from Genzyme; participated in speaker’s bureau for Novartis, Genzyme, and Biogen.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, B.E., Lakin, L., Binns, C.C. et al. Patient and Provider Insights into the Impact of Multiple Sclerosis on Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Neurol Ther 10, 99–119 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00240-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00240-9