Abstract

Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is characterized by systolic blood flow reversal from the left ventricle to the left atrium. A 2019 study indicated that in the USA, clinically significant MR (sMR) is associated with a substantial healthcare cost burden. In Taiwan, few data are available to describe the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and economic burden of patients with sMR.

Methods

Using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), a national, detailed claims database of all 23 million residents of Taiwan, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify patients with sMR and quantify the impact of the disease on Taiwan’s healthcare system. We classified patients with sMR into three cohorts based on disease etiology: functional MR (sFMR), degenerative MR (sDMR), and uncharacterized MR (sUMR).

Results

We compared patient characteristics across cohorts and estimated attributable healthcare utilization and costs during the 12-month follow-up period. Our research shows that in Taiwan, patients with sFMR were older, sicker, and presented at casualty (emergency department) more frequently than those with sDMR and sUMR. Meanwhile, patients with sDMR had the highest 12-month healthcare expenditures across the cohorts.

Conclusion

These findings are inconsistent with what has been shown in the USA, which warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The number and healthcare burden among patients with MR/sMR are unclear. |

We therefore investigated the patient number, clinical visit, length of stay, and medical expenditure in patients with MR/sMR. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients with FMR/sFMR were older and sicker and presented at casualty (emergency department) more frequently than patients with other types of MR. |

sDMR had the highest 12-month healthcare expenditure among sMR cohorts and is inconsistent with what has been shown in the USA. |

Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) can occur as a result of aging, rheumatic damage, heart attack, or mitral valve prolapse, any of which may prevent the mitral valve from closing completely [1]. MR is one of the most frequently occurring heart valve diseases (HVDs) in the USA and a common HVD in patients receiving surgery in Europe [2, 3]. Because the prevalence of MR increases with age (9.3% in individuals over 75 years old and older compared with 1% in those 55–64 years old), and because of the rate at which the population is aging, the number of MR cases is expected to double by 2030 [4, 5].

MR is classified into two major categories: degenerative (primary) MR, due to intrinsic leaflet abnormality; and functional (secondary) MR, due to distortion of the mitral valve [6]. Although the incidence of rheumatic heart disease has substantially reduced over the years, the incidence of MR has increased recently [4]. Identifying the cause and type of MR is important to determine the most appropriate management [7]. Medications used for treating MR are intended to decrease body fluid volume and lower blood pressure, subsequently reducing the load on the heart. But because they do not address the leaflet or valve abnormalities, the effects of these medications on MR are limited and show no change in life expectancy [8]. In fact, asymptomatic patients with severe MR (sMR) have demonstrated increased mortality under medical management [9]. Even in patients with symptomatic sMR whose symptoms have been diminished by medications, mitral valve surgery is indicated [10].

A study has shown that MR and its comorbidities impact patients’ quality of life and increase healthcare utilization [11]. Another study has found that sMR increases the complexity of the disease and is associated with a substantial healthcare burden [12]. Additionally, when comparing the three different types of severe disease—functional MR (sFMR), uncharacterized MR (sUMR), and degenerative MR (sDMR)—the annual healthcare cost was higher for patients with sFMR versus those with sUMR or sDMR [12].

Although several studies have reported on the medical care costs of MR, evidence on the direct healthcare costs of MR and data on the comparisons between the different MR types remains limited [13, 14]. Studies have focused on Western populations or business insurance populations and provided little evidence on the healthcare cost for MR in Asians. Additionally, most studies have not fully addressed the comorbidities and etiology of MR. To bridge these gaps, this study focused on the healthcare burden of MR and sMR in the whole population in Taiwan. Additionally, it investigated the differences in healthcare utilization between subjects with different types of MR using data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

Methods

Data Source and Patient Definition

The data for this retrospective, population-based study were acquired by accessing claims records from the NHIRD from 2016 to 2018. The NHIRD contains details of all beneficiaries in Taiwan (23,948,108 individuals in 2018). Taiwan’s NHIRD is a public database available through a formal application and approved by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-2500-113.html). The study was approved by the MacKay Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Board Taiwan R.O.C. (Protocol Number 19MMHIS083e).

The International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) diagnosis and procedure codes were used to identify patients with MR. The design used in this study was similar to that of a study of Medicare fee-for-service patients in the USA [12]. In this current study, patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) patients who were 18 years of age or older with at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims with MR diagnosis between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2018; (2) those with baseline data at least 6 months before the first MR diagnosis and follow-up data at least 6 months after (landmark period); and (3) those whose healthcare utilization was measured for at least 12 months after the landmark period. Patients who had a record of at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims for mitral stenosis or rheumatic insufficiency were excluded from the study. Patients were divided into three cohorts (degenerative mitral regurgitation (DMR), functional mitral regurgitation (FMR) and unidentified mitral regurgitation UMR) based on disease etiology. Patients were assigned to one of the three cohorts in the following order: (1) patients with a record of chordal rupture were classified as DMR; (2) patients with a record of at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims with a diagnosis of heart failure (HF) during the 6-month baseline or landmark period were classified as FMR; (3) patients without at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims with a diagnosis of HF or ischemia during the baseline or follow-up period were classified as DMR; and (4) patients not meeting any of the aforementioned criteria were classified as UMR. We further defined sMR in these patients with MR. Patients were considered to have sMR if they met any of the following criteria: (1) pulmonary hypertension or atrial fibrillation during the baseline or landmark period or (2) chordal rupture, MR surgery, or two or more echocardiograms during the landmark period.

Assessment

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to measure the chronic disease severity. Patients with MR and 12-month follow-up period after the landmark period were evaluated for their healthcare utilization based on casualty visits, all-cause inpatient hospitalization, MR- or HF-related inpatient hospitalizations, and length of stay (LOS). To further understand the disease burden of these patients with MR, health expenditures were studied, and the exchange rate of NTD to USD was 1:32.

Data Analysis

SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used to perform all data analyses. Variable measures were identified on the basis of the aforementioned criteria. Frequencies or percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Differences in baseline characteristics and outcomes were assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test and one-way analysis of variance, as appropriate. P values of less than 0.05 were used to denote statistical significance.

Results

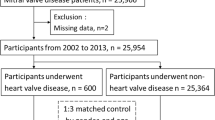

From 2016 to 2018, the entire population in the NHIRD was used to establish the cohort in this study (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria identified 35,933 eligible MR cases from 2016 to 2018 (0.15% of the total population). These patients were divided into three groups (DMR, FMR, and UMR). Among these eligible patients, 70.75% were classified as DMR, 23.74% as FMR, and 5.51% as UMR. These patients were then subdivided according to the clinically significant criteria. The sMR cohorts were as follows: 0.99% of the patients had sDMR, 30.99% had sFMR, and 86.07% had sUMR (Table 1). Both FMR and sFMR cohorts were older than the other cohorts (DMR/UMR or sDMR/sUMR). The average age of the FMR cohort was 69.04 years, whereas the DMR cohort had an average age of 55.38, and the UMR cohort had an average age of 68.35. The average age of the sFMR cohort was 72.45 years, whereas those of the sDMR and sUMR cohorts were 61.13 and 68.75, respectively. The DMR cohort had more female patients (63.32%) than the FMR (54.05%) or UMR (50.30%) cohort. Whereas, the sDMR cohort had more male patients (64.68%) than the sFMR (49.53%) or sUMR (51.64%) cohort (Table 1). The CCI in the FMR cohort was 3.09, which was three times higher than that in the DMR cohort (0.95) and twice as high as that in the UMR cohort (1.79) (Table 2). The prevalence of almost all underlying diseases in the FMR cohort were higher than those in the DMR and UMR cohorts, except for cerebrovascular disease and cancer in the UMR cohort. The prevalence of all underling diseases were higher in the UMR cohort than in the DMR cohort. The CCI in the sFMR cohort was 3.22, which was approximately two times higher than those in the sDMR cohort (1.77) and the sUMR cohort (1.59) (Table 2). The prevalence of almost all underlying diseases was higher in the sFMR cohort than in the sDMR and sUMR, except for myocardial infarction/rheumatic disease in the sDMR cohort and mild liver disease in the sUMR cohort. The prevalence of all underling diseases was higher in the UMR cohort than in the DMR cohort. However, the difference in the prevalence of underling diseases between the sUMR and sDMR cohorts was not as significant as that between the UMR and DMR cohorts.

The healthcare utilization data for patients with MR were collected 12 months after the landmark period (Table 3). To ensure that the complexity of MR was well measured, MR/HF/all-cause casualty visits, hospitalizations, LOS, and outpatient department (OPD) visits were calculated. Patients with FMR had the highest utilization patterns in both casualty visits and hospitalizations for MR/HF/all-cause. The average number of casualty visits per year of more than half of patients with FMR was 1.58, versus 0.61 for DMR and 1.20 for UMR (Table 3). The frequency of casualty visits for patients with DMR and UMR was lower than that for patients with FMR. Patients with FMR also showed higher frequency of hospitalizations than those with DMR or UMR. The average LOS was higher in patients with FMR (14.83 days) than in patients with DMR and UMR (3.18 and 7.68 days, respectively). The average number of casualty visits per year of two-thirds of patients with sFMR was 2.04 (Table 3). The frequency of casualty visits for patients with sDMR and sUMR was lower than that for those with sFMR. However, patients with sDMR had the highest utilization patterns in hospitalizations for MR/HF/all-cause. Patients with sDMR also showed higher rates of hospitalizations than patients with sFMR or sUMR. The average LOS was higher in patients with sDMR (31.51 days) than in patients with sFMR and sUMR (23.02 and 7.94 days, respectively). The annual healthcare expenditures were higher in patients with FMR ($8172) than in patients with DMR and UMR ($2450 and $5450, respectively) (Fig. 2). However, the annual healthcare expenditures were higher in patients with sDMR ($20,031) than in patients with sFMR and sUMR ($11,481 and $5451, respectively).

Discussion

This study analyzed the epidemiological and healthcare utilization data for patients with MR and sMR between 2016 and 2018 using Taiwan’s NHIRD. The prevalence of eligible MR cases was 0.15% of the total population. Patients aged 51–60 years in the DMR cohort, 71–80 years in the FMR cohort, and 61–70 years in the UMR cohort demonstrated a higher prevalence of MR (23.16%, 24.45%, and 26.74%, respectively) (Table 1). The number of patients with DMR was higher than those of patients with FMR and UMR in this study. However, the number of patients with sFMR was higher than those of patients with sDMR and sUMR. In analyzing the healthcare utilization and annual expenditure for patients with MR and sMR, we found—as expected, due to its high CCI score and high incidence of comorbidities—higher utilization and expenditure associated with FMR compared with DMR and UMR. The DMR cohort had the lowest risk of comorbid conditions and healthcare utilization compared with the FMR and UMR cohorts (Table 2 and Fig. 2). For patients with sMR, other studies have reported that those with sFMR often have more comorbidities than the other cohorts, which may be associated with higher medical care costs. However, these results were in contrast to ours [12], which showed that, although the sFMR cohort showed a high prevalence of comorbidities, its healthcare utilization and annual expenditure were actually lower than those of the sDMR cohort. Severe MR can cause HF or heart rhythm problems [3]. In our study the prevalence of congestive HF dramatically increased from 1.75% in the DMR cohort to 39.49% in the sDMR cohort; whereas the FMR and sFMR cohorts were similar at over 90%. Prakash et al. found that the prevalence of HF increased from 10.5% in MR to 18.8% in sMR [15]. In another study, the estimated annual expenditure in the sMR with HF cohort was higher than that in the MR with HF cohort ($23,988 versus $21,702). This may be the reason why the annual expenditure in the sDMR cohort in this study was eight times higher than that in the DMR cohort and even higher than that in the sFMR cohort.

The frequency of casualty visits and hospitalizations and the LOS in this study were significantly higher than those in other studies [12, 13]. These results may be due to the character of healthcare in Taiwan—the National Health Insurance scheme and low cost give patients easy access to medical care [16]. In a study of patients in Taiwan with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the mean number of OPD visits per year in healthy controls was 20.4, and the mean number of OPD visits per year in patients with CKD was 29.1–50.9 (stage 1–5) [17]. In this current study, the average number of OPD visits in patients with MR and sMR range from 29.84 to 36.70 and from 27.98 to 35.79, respectively (Table 3). This number of OPD visits was close to those seen in the study of patients with stage 1 and stage 2 CKD, indicating that the severity of MR/sMR may be similar to that of stage 1 and stage 2 CKD.

This study was conducted to examine the difference between MR and sMR and determine the factors that may influence the annual expenditure for sMR within a real-world population of patients. As observed in our results, sMR was associated with higher frequency of hospitalizations versus MR for all-cause/HF/MR. Underlying this is the fact that, as seen in our previous study [18], only a small number of patients undergo mitral valve repair, despite it being a guideline-recommended intervention for sMR [19,20,21]. While the underuse of surgical repair has not been studied vis-à-vis its effects on healthcare utilization and expenditure, this previous study nonetheless points to a common weakness in the treatment of sMR, since the operative risk in most mitral valve procedures is low, even when accounting for surgical outcomes that depend on multiple factors (e.g., patient status, repair technique, and physician experience) [22].

This study has several limitations owing to its claim data design. First, certain information was unavailable, including self-payment, laboratory data, disease severity, family history, and personal information (e.g., height and weight). Some diseases or procedures were declared by the Diagnosis Related Group payment system, which means that the specific medical resources used were not given. Second, coding errors, misclassifications, or other coding-related mistakes happen in the real world. Because the selection criteria for patients in this study were based on ICD diagnosis and operation codes, it is possible that errors unintentionally influenced the selection of patients. Third, a range of factors—including clinical policies, reimbursement guidelines, and medical equipment and usage—may change over time, including during the observation period, which could affect the outcomes. Finally, because Taiwan moved from ICD-9 to ICD-10 in 2016, we chose to begin the observation period in 2016 to avoid mixing codes (i.e., ICD-9 versus ICD-10). This resulted in a shorter observation period, which may impact the results, as fewer patients were included.

Conclusions

In this real-world, population-based national study, we found that patients with FMR/sFMR were older and sicker and presented at casualty more frequently than patients with DMR/sDMR and UMR/sUMR. Among MR types, FMR had the highest 12-month healthcare expenditure. However, patients with sDMR had the highest 12-month healthcare expenditure among sMR cohorts. This finding is inconsistent with what has been shown in the USA, which warrants further investigation. Further treatment options and their associated clinical and economic outcomes should be studied in the real world.

References

Turi ZG. Cardiology patient page. Mitral valve disease. Circulation. 2004;109:e38–41.

Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231–43.

Enriquez-Sarano M, Akins CW, Vahanian A. Mitral regurgitation. Lancet. 2009;373:1382–94.

Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005–11.

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–492.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159–95.

Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2018;71:110.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:e57-185.

Enriquez-Sarano M, Avierinos JF, Messika-Zeitoun D, et al. Quantitative determinants of the outcome of asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:875–83.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:252–89.

Trochu JN, Le Tourneau T, Obadia JF, Caranhac G, Beresniak A. Economic burden of functional and organic mitral valve regurgitation. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;108:88–96.

Mehta HS, Houten JV, Verta P, Gunnarsson C, Mollenkopf S, Cork DP. Twelve-month healthcare utilization and expenditures in Medicare fee-for-service patients with clinically significant mitral regurgitation. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8:1089–98.

Moore M, Chen J, Mallow PJ, Rizzo JA. The direct health-care burden of valvular heart disease: evidence from US national survey data. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:613–27.

McCullough PA, Mehta HS, Barker CM, et al. The economic impact of mitral regurgitation on patients with medically managed heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:1226–31.

Prakash R, Horsfall M, Markwick A, et al. Prognostic impact of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (MR) irrespective of concomitant comorbidities: a retrospective matched cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4: e004984.

Yeh MJ, Chang HH. National health insurance in Taiwan. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:1067.

Huang RY, Lin YF, Kao SY, Shieh YS, Chen JS. A retrospective case-control analysis of the outpatient expenditures for western medicine and dental treatment modalities in CKD patients in Taiwan. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e88418.

Chung CH, Wang YJ, Lee CY. Epidemiology of heart valve disease in Taiwan. Int Heart J. 2021;62:1026–34.

Bach DS, Awais M, Gurm HS, Kohnstamm S. Failure of guideline adherence for intervention in patients with severe mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:860–5.

Asgar AW, Mack MJ, Stone GW. Secondary mitral regurgitation in heart failure: pathophysiology, prognosis, and therapeutic considerations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1231–48.

Dziadzko V, Clavel MA, Dziadzko M, et al. Outcome and undertreatment of mitral regurgitation: a community cohort study. Lancet. 2018;391:960–9.

De Bonis M, Alfieri O, Dalrymple-Hay M, Del Forno B, Dulguerov F, Dreyfus G. Mitral valve repair in degenerative mitral regurgitation: state of the art. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60:386–93.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, was supported by the Mackay Medical College (Sanzhi, Taiwan; grant nos. MMC-RD-109-CF-G1-01, MMC-RD-110-CF-G001-01, MMC-RD-111-1B-P014 and MMC-RD-111-CF-G001-01) and Edwards Lifesciences (Taiwan) Corp to Ching-Hu Chung. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, or data interpretation.

Authorship

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this article and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Concept and design, CH Chung; Methodology, CH Chung, YJ Wang and CY Lee; Formal analysis, CH Chung; Investigation, CH Chung, YJ Wang and CY Lee; Drafting the manuscript, CH Chung; Writing—review and editing, CH Chung, YJ Wang and CY Lee.

Disclosures

Yu-Jen Wang and Chia-Ying Lee are employees of Edwards Lifesciences, one of the study sponsors. The authors were responsible for this publication without a financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Ching-Hu Chung has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Our study was approved by the MacKay Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Board Taiwan R.O.C. (Protocol Number 19MMHIS083e).

Data Availability

This study is based on data from Taiwan’s Health and Welfare Data Science Centre at Ministry of Health and Welfare (H108111). The data underlying this study belong to the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan and cannot be made publicly available due to legal restrictions. However, the data are available through formal application to the Health and Welfare Data Science Centre at Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-2500-113.html) and require a signed affirmation regarding data confidentiality. The authors have no special privilege of access to the database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, CH., Wang, YJ. & Lee, CY. One-Year Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures Among Patients with Clinically Significant Mitral Regurgitation in Taiwan. Cardiol Ther 12, 159–169 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-022-00294-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-022-00294-2