Abstract

Zirconia nanoparticles were synthesized by a solution combustion technique. Zirconia nanoparticles were grown inside alumina templates to control the crystal size. The alumina templates were characterized by pores of sizes of approximately 6–8 nm. X-ray diffraction line profile analysis using Williamson–Hall method and Warren and Averbach revealed that the alumina templates were characterized by negligible defect-related effect of lattice distortion. Rietveld structure refinement did not reveal any gross difference with the literature reported values for cell parameters ‘a’ and ‘c’ and fractional atomic coordinates x and z for Al and O atoms indicating no large-scale bond deformation. The template X-ray reflections in the nanocomposites are skewed in nature which indicates some distortion of the templates might have taken place. The distortion is, however, plastic in nature which is evident from the higher level of lattice distortion viz. 0.2% of lattice microstrain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stabilized zirconia (ZrO2) ceramics finds application in diverse fields. The fully stabilized (cubic) zirconia (FSZ) is used for heating elements, oxygen sensors and fuel cell applications. Partially stabilized zirconia (PSZ) or tetragonal zirconia particles (TZP) (a mixture of cubic and tetragonal or single-phase tetragonal) find application in mechanical and structural applications like thermal barrier coatings and as toughening agents in many ceramic composites viz. zirconia-toughened alumina (ZTA) ceramics. Pure zirconia (ZrO2) with cubic and tetragonal structures, respectively, exists only at high temperatures typically above 1200 °C below which only monoclinic phase exists. The cubic (fluorite) crystal structure of ZrO2 can be described as the Zr+4 ions forming a cubic close pack structure (FCC lattice) with the O2− ions occupying all the tetrahedral holes [1].

With the decrease in temperature, ZrO2 undergoes a cubic to tetragonal (c → t) phase transition at around 2380 °C and a tetragonal to monoclinic (t → m) phase transition at around 1205 °C [2, 3]. At the cubic to tetragonal phase transition, the fluorite cubic structure distorts to the tetragonal structure with the tetragonal c-axis parallel to one cubic \(\left\langle {001} \right\rangle\) axes. On the other hand, the tetragonal to monoclinic phase transition is characterized by a martensitic phase transition accompanied by large hysteresis in the phase transition temperature, greater than 200 °C and the generation of large shear and volume elastic strains in the monoclinic phase. It has been observed that the martensitic transformation temperature for the t → m can be brought down significantly by adding additives of suitable characteristics which facilitate the stabilization of the tetragonal phase [4, 5].

Addition of appropriate dopant cations viz. Y3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Ce4+, etc. is known to stabilize the tetragonal and cubic polymorphs. Phase stability at room temperature of such materials and their dependence on particle/crystallite size has been extensively studied by numerous researchers [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Despite such effort, the fundamental issues concerning the atomistic origin of phase stability with a special reference to size stabilization and origin of lattice microstrains of t- and c-ZrO2 polymorphs are still unresolved especially in undoped zirconia ceramics. The charge compensating oxygen vacancies in doped ZrO2 hold the key to ionic conduction in these ceramics. The simultaneous presence of dopant cations and oxygen vacancies in large concentration means the local atomic environments in the stabilized materials are very different from the corresponding stoichiometric (t and c phases) phases. Hence, there is urgent need of characterizing the local atomic structure in the real space.

Recent advance in the nanostructure research indicates that valence of Zr ions decreases with decreasing particle size suggesting the occurrence of oxygen deficiency in tetragonal ZrO2−δ (0 < δ<1) where δ is the vacancy concentration. This opens up a relevant question whether size-stabilized t-ZrO2 or even c-ZrO2 (formed as a result of more distortion of the oxygen sublattice) is actually an oxygen deficient one, and a detailed structural analysis (both long and short range) of ZrO2 nanoparticles may solve the controversy.

Theoretical formulation

The study of lattice imperfections in crystalline materials is an important aspect of microstructural characterization. Among the currently used methods, X-ray diffraction line profile analysis (XRDLPA), in particular, describes the microstructure in terms of parameters such as coherent domain sizes or crystallite sizes, lattice microstrains, stacking fault probabilities, etc. Broadening of X-ray diffraction peaks is a consequence of both small crystallite size and lattice distortion therein. Methods have been developed over the past few decades to separate these two general effects along with other effects such as planar or twin faults [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. These, however, do not provide a direct and realistic physical picture of the microstructure in general. The concept of crystallite size is also superfluous. For example, nanocrystalline materials which are of current interest as technologically potential materials exhibit certain properties which are sensitive to the grain sizes and/or their distribution. The X-ray methods yield certain averages (area or volume averages) of coherent domain sizes conceived as ensemble of columns of unit cells in a direction perpendicular to the diffracting planes. These average column lengths do not necessarily conform to the average grain sizes measured from TEM. Further, it is often tedious to determine both the average grain size and their distribution representative of the whole sample using TEM.

Integral breadth methods

For rapid analysis of microstructure of materials, generally, the full width at half maxima (FWHM, 2ω) or the integral breadth (β) is employed. Mathematically, the integral breadth is defined as,

The fundamental limitation of using the integral breadth is to ascribe analytical profile shapes to facilitate deconvolution. The most widely used function which can be readily and analytically deconvoluted is the Cauchy and Gaussian functions. According to Langford [14], a better approximation would be a Voigt function which is a convolution of a Cauchy and a Gaussian function. Langford derived an explicit equation for a Voigt function and showed that the breadth of Cauchy and Gaussian part can be obtained from the value of 2ω/β (= φ, called the shape factor) by graphical method. de Keijser et al. [15] derived some empirical relations for the same.

Size–strain analysis

The size–strain analysis in terms of integral breadths is simple enough if either crystallite size broadening or microstrain broadening is present, and can be performed easily using either Scherrer equation or Wilson’s equation [13,14,15]. If both are present simultaneously, specific assumptions regarding the order dependence of broadening and\or analytical functional forms for size- and strain-broadened profiles are necessary.

In single-line analysis, it is assumed that the Cauchy component of the Voigt function gives the value of crystallite size and the Gaussian component gives the value of strain. Thus, the crystallite size can be obtained from the relation

and the upper limit of the microstrain is obtained from the relation

If size and strain broadening is present simultaneously, it is customary to assume the nature of the size- and strain-broadened profile. Schoening [16] suggested Cauchy size-broadened profile and Gaussian strain-broadened profile and proposed graphical method for separation of size and strain effects. Earlier Williamson and Hall [17] assumed that both size- and strain-broadened profile are of Cauchy nature. Based on these assumptions, following equations can be used for multiple-line analysis

where, D is the crystallite size, ε is the strain and s is (2sinθ/λ).

Equation 4 is called Williamson–Hall equation; Eq. 5 is similar to the Halder and Wagner [18] approximation for the integral breadth of a Voigt function; Eq. 6 is valid for Gaussian assumption for both size- and strain-broadened profile. If β for two or more order of a same family of reflection is known then the crystallite size and strain may be obtained from the above equations.

Fourier method

If both small crystallites and microstrain broaden the X-ray diffraction lines, a more detailed and rigorous analysis was developed by Warren and Averbach [12] through the developments of Bertaut [19] and combining Stokes’ [20] method of deconvolution based on Fourier representation of line profiles.

Warren and Averbach method

A measured X-ray diffraction line profile can be expressed in a Fourier series as

where K is approximately a constant, A and B are the cosine and sine Fourier coefficients and L is a distance perpendicular to the diffracting planes. In practice, L takes specific discrete value nΔL, n is an integer and ΔL is inversely proportional to the length of the measurement range in the reciprocal space, and

The Fourier coefficients of a structurally broadened line profile (obtained from a deconvolution procedure) can be written as the product of order-independent size Fourier coefficients AS(L) and the order-dependent strain Fourier coefficients AD(L,s), and the formal cosine Fourier coefficient is expressed as

To obtain information on AS(L) and AD(L,s) separately, two orders of reflection have to be measured. In the original analysis of Warren and Averbach, the size–strain separation is done by taking the logarithm of Eq. 9 giving

From the theory of Warren, AS(L) and AD(L,s) are expressed, respectively, as Nn/N and \(\left\langle {{ \cos }(2\pi Ls\varepsilon_{L} )} \right\rangle\) where Nn represents the number of columns n cells long and N is the total no. of cells in the sample. Substituting and taking approximation, Eq. 10 reduces to

For two orders of reflection, a plot of ln A(L,s) against s2 gives Nn/N from intercept and \(\left\langle {\varepsilon^{2}_{L} } \right\rangle\) from the slope. Nn/N in the limit n → 0 is defined as the average column length \(\left\langle D \right\rangle_{\text{eff}}\) .

Rietveld method

The basic drawback of conventional Warren–Averbach method is the accurate description of the profile tails which is often impossible to determine in case of samples showing considerable peak overlap (viz. materials of lower symmetry). A generally accepted solution of this above shortcoming is to resort to the profile fitting methods. The primary objective of profile fitting is to fit a numerical function specifically referred to as profile shape function (PSF) to a measured diffraction line. Each PSF is typically described by three parameters and sometimes a fourth for a tunable PSF. They are (1) the line position 2θ0, (2) peak or integrated intensity I0, (3) line width expressed as FWHM. An optimizing algorithm is employed to adjust the PSF’s parameters until the differences between the observed and calculated lines are minimized. Early X-ray Rietveld studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27] and integral breadth methods discarded the assumption of simple profile shape functions like the Gaussian or Cauchy (Lorentzian) for X-ray line profiles and established that tunable functions like Voigt, pseudo-Voigt and the Pearson VII functions are likely to be the better choice for X-ray line profiles. In the Rietveld method, the whole diffraction pattern is fitted simultaneously and it requires a detailed structural model (viz. site occupancies, fractional atomic coordinates, etc. apart from the unit cell dimensions).

Experimental

Synthesis of alumina templates and alumina–zirconia nanocomposite

It is well known that undoped tetragonal/cubic phase of ZrO2 can be stabilized at room temperature by controlling the size of the crystallites [28]. Thus, in order to synthesize stable ZrO2 nanoparticles which retain tetragonal/cubic crystal structure at room temperature, it is essential to prepare templates with pores less than 100 nm. α-Al2O3 is one such inorganic template which has very limited solute solubility in zirconia and thus will not alter the local environment of the Zr atoms in the lattice. Analysis of crystal structure of such nanocomposites may give information regarding the oxygen vacancies if any, hence its implication on phase transformation and phase stabilization.

Solution combustion synthesis (SCS) (Aruna et al. and references therein [29]) is a quick and simple process for the synthesis of a variety of nano-sized materials. The process involves a combustion reaction in solution phase of different oxidizers (e.g. metal nitrates) and fuels (e.g. urea, glycine, hydrazides). The combustion reaction is usually initiated in a pre-heated furnace or on a hot plate at a much lower temperature. In a typical reaction, a homogeneous mixture of water, metal nitrate precursors and fuel is allowed to dehydrate leading to the exothermic decomposition of the fuel. The chemical energy released from the exothermic reaction between the metal nitrate and fuel appears as large amount of heat which is sufficient enough to raise the temperature of the system to higher value (> 1600 K) for a short duration of time. As a result of decomposition of the fuel and the nitrate, a sudden evolution of large volume of gas occurs. This makes large particles or agglomerates get disintegrated leading to the formation of materials, which can be easily crushed to obtain fine particles. Another important aspect of combustion synthesis is the formation of porous material which will serve the purpose of templates in the present study.

Metal nitrates were chosen as precursors to prepare the alumina templates as well as alumina–zirconia composites. Micron-sized α-Al2O3 was prepared by the combustion of aluminium nitrate [Al(NO3)3·9H2O; LR grade, LOBA CHEMIE] and urea [NH2CONH2; GR grade, MERCK] mixture in the molar ratio 1:2.5 [30]. Redox mixture of aluminium nitrate and urea was dissolved in minimum quantity of double-distilled water, and the dish containing the solution was introduced into a furnace maintained at temperature 500 ± 10 °C. The solution boils, foams, ignites to burn with flame and produces voluminous foamy alumina powder. The as-prepared α-Al2O3 sample was annealed at a temperature of 800 °C in a muffle furnace for 10 h to determine any change in the microstructural properties. The Al2O3–ZrO2 composites with a 50:50 ratio were prepared by combustion technique using aluminium nitrate–urea and zirconyl nitrate [ZrO(NO3)2·H2O; LR grade, LOBA CHEMIE]. The stoichiometry of metal nitrate and fuel is calculated using their total oxidizing and reducing valances in such a way that the equivalence ratio is unity and maximum energy is released during combustion.

Sample characterization

The X-ray powder diffraction pattern of the as-prepared and annealed samples as well as that of the standard material (here fully recrystallized Si powder [31]) was taken at room temperature in a highly stabilized Philips PW1830 X-ray generator using a Ni-filtered Cu Kα radiation. A divergence slit of opening 1 deg in the primary beam and a receiving slit of width 0.1 mm in the secondary was used for data collection. The data were collected in a step-scan mode with a step size of 0.02 deg 2θ and the counting time of 10 s per step.

Data analysis

In the present study, we have adopted a modified Rietveld refinement procedure to obtain refined structural (atomic coordinates, thermal parameters, etc.) and microstructural parameters (coherent domain size/crystallite size, microstrain, etc.). The whole pattern fitting has been done with the help of the software MAUD [32]. Initial simulation of the diffraction pattern was carried out with the help of following structural information: (1) α-Al2O3 phase with space group R\(\bar{3}\)c and lattice parameters a = 4.7607°A and c = 12.997°A according to the JCPDS card no. 88-0826 and (2) tetragonal ZrO2 with space group P42/nmc with lattice parameters a = 3.629°A and c = 5.197°A according to the JCPDS card no. 89-7710. The X-ray diffraction patterns of the standard material and the prepared composites were fitted with pseudo-Voigt function convoluted with a truncated asymmetric function. The background was fitted with a fourth-order polynomial. The instrumental function was determined by measuring the intensity across 10 peaks of fully recrystallized Si powder [31] having large crystallites and free from any defect broadening. The instrumental parameters (viz. three Caglioti parameters [21, 22, 33] for FWHM, two for Gaussian content of the profiles and two asymmetry parameters) were set as non-refinable with the values obtained from the fitting of the X-ray diffraction pattern of the standard material. The microstructural parameters such as coherent domain/crystallite size \(\left\langle {D_{\text{eff}} } \right\rangle\) (\(\left\langle {D_{\text{eff}} } \right\rangle\) is also defined as area-averaged effective crystallite size), rms microstrain \(\left\langle {\varepsilon^{2} } \right\rangle^{1/2}\), etc., along with lattice parameters and structural coordinates were held as refinable parameters during Rietveld refinement. The goodness-of-fitting is judged by the reliability parameters Rwp.

Results and discussion

Characterization of α-alumina templates

Figure 1 below shows the TEM micrographs of the as-prepared α-Al2O3 templates. Pores of sizes of approximately 6–8 nm are readily observed. The porous structure results from the escape of the gaseous products during combustion synthesis. It is thus clear that combustion synthesis is capable of producing templates for further synthesis of zirconia nanoparticles inside the templates and control of crystal size can be achieved.

The SEM micrographs of the as-prepared as well as annealed samples are shown in Fig. 2. The SEM micrographs show flake-like appearance of the α-Al2O3 particles with approximate sizes of 0.5 μm or less. Further, the particles have approximately hexagonal morphology. The X-ray diffraction pattern of the as-prepared sample is shown in Fig. 3. The X-ray diffraction lines are in conformity with PDF card no 88-0826 corresponding to α-Al2O3 phase.

Preliminary analysis: X-ray diffraction line profile fitting

The as-prepared α-Al2O3 sample produces a diffraction pattern with large number of peaks. The profile fitting analysis was performed for [012] and [113] crystallographic directions which exhibited least degree of overlapping. A profile fitting methodology was used to determine the profile shape parameters and the hence the total integral breadth of the corresponding X-ray diffraction lines. The profile shape was assumed to be a pseudo-Voigt function numerically convoluted with a truncated exponential function [22]. In the fitting process, the Gaussian content (η), the half width at half maximum (ω), the peak height (Io) and the Bragg 2θ position were simultaneously refined along with the parameters of the linearly varying background. The integral breadth of the profiles is computed according to the relation \(\beta = \omega \left[ {\pi \left( {1 - \eta} \right) +\eta \left( {\pi /\ln 2} \right)^{{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}}}} } \right]\). The Cauchy and Gaussian component of the integral breadths of the ‘true’ specimen-broadened profile and the total integral breadth of the samples were obtained according to the formalism described by de Keijser et al. [15]. A similar analysis was performed for the annealed sample and the alumina–zirconia composite.

Williamson–Hall plots

A simple qualitative information regarding the nature of the coherently diffracting domain (i.e. morphology, size–strain information, etc.) prior to any detailed analysis may be obtained on the basis of a Williamson–Hall (WH) plot. Figure 4 shows the WH plot for both the as-prepared, annealed and the first few alumina reflections of alumina–zirconia composite sample. In general, for a linear version of the Williamson–Hall analysis, the broadening due to crystallite size and microstrain is additive in nature according to the relation βF * (total integral breadth in sinθ scale) = βsize + βstrain (s).

The Williamson–Hall plot for both the as-prepared and annealed sample shows some unusual features. The WH plot is neither constant with the increase in the diffraction vector (the case of pure size broadening), nor it increases linearly with the diffraction vector (the case of pure strain broadening). It is observed that the true integral breadth increases nonlinearly with the diffraction vector d*. Linear fit produces very low crystallite size, and the values are different for the different regions of extrapolations assumed. This confirms further the observed nonlinearity of the Williamson–Hall plot. The few scattered points in the high s region could be attributed to inaccuracy in pattern decomposition from overlapping reflections. Annealing at 800 °C does not produce any appreciable change in the WH plot apart from slight increase in the crystallite size as evident from the intercept of the plot. However, the same alumina reflections show different behaviour in the composites and show lower crystallite as well as higher microstrain. Higher alumina reflections did not yield reliable data due to high degree of overlapping.

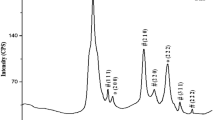

Rietveld refinement

Rietveld refinement was carried out with the Rietveld program MAUD as described in an earlier section. Figure 5 shows the Rietveld refinement result. Table 1 lists the fitting parameters and their errors. It is clear from Fig. 3 and Table 1 that a good fit is observed. The microstructural model involved in the Rietveld refinement is an isotropic size–strain model. The amount of microstrain in the material is negligible and is in conformity with the earlier crude method of Williamson–Hall. It is further clear from the table that there is marginal vacancy in the oxygen site. The structural parameters like z and x displacement are in gross agreement with the literature values.

Characterization of nanocrystalline zirconia in alumina templates (50:50)

The novel combustion route for the preparation of nano-zirconia–alumina composite (nZA) powders has been described previously. X-ray diffraction pattern of the nZA powders was analysed using a position-constrained pattern decomposition method assuming a pseudo-Voigt profile shape function convoluted with a truncated exponential asymmetric function using nonlinear least squares algorithm. Figure 6 shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the nZA powder. The diffraction pattern of alumina templates is also shown for comparison. The presence of only tetragonal phase of zirconia could be revealed. One significant result of the X-ray diffraction study is the asymmetry of the most of the alumina reflections in the low angle side of the peaks. The extent of this skewness is more in zirconia–alumina composites compared to only alumina produced by the same method. It is thus clear that the observed asymmetry is sample-dependent and is not wholly due to instrumental effect.

Microstructural characterization of zirconia particles and alumina templates

Using a single-line integral breadth technique as described earlier, the crystallite sizes \(\left\langle {D_{v} } \right\rangle\) (volume weighted) and microstrain of the tetragonal phases of zirconia for different crystallographic directions were obtained. The results are shown in Table 2. The crystallite size varies between 200 and 300 Å, whereas the upper limit of microstrains varies between 0.15 and 0.6%. The significant Gaussian peak shapes of the alumina samples indicate large crystallite size and prominent strain broadening. Table 2 also shows the results of Warren–Averbach analysis as applied to separate the size and strain contributions along the [111] crystallographic direction for the tetragonal zirconia phase. The average crystallite size obtained from both WA and integral breadth analysis is in good agreement.

The result of Warren–Averbach analysis for alumina [012] crystallographic direction in the as-prepared and alumina–zirconia templates is given in Table 3. It is observed from Table 3 that the value of rms microstrain obtained from the Warren–Averbach analysis is independent of the deconvolution standard used. It is thus clear from the analysis that incorporation of zirconia particles in the alumina matrix results in localized deformation in the alumina matrix, and the possible origin of strain is in the interfacial regions of the alumina–zirconia matrix. The result also explains higher level of microstrain in the alumina matrix as observed from the Williamson–Hall plot (Fig. 4).

It is clear from Table 4 that there is a decrease in crystallite size and increase in the lattice microstrain. This indicates that zirconia crystallites incorporated inside the alumina pores leads to more defects in the alumina matrix. To further supplement the above analysis, Rietveld refinement of the alumina–zirconia sample was performed according to the procedure as described earlier using an isotropic size–strain broadening microstructure model. Figure 7 shows the fitted data along with the residual, and Table 4 lists the fitting parameters.

Comparing the parameters of Tables 1 and 4, it is clear that much higher value of lattice microstrain and a lower value of crystallite size are obtained for the template alumina. It is hence clear that the zirconia particles has grown inside the pores of the alumina templates and the difference of thermal expansion coefficients of alumina and zirconia might have introduced residual stresses in the alumina matrix and may have thus resulted in higher values of lattice microstrain.

Conclusion

Zirconia nanoparticles were synthesized by a solution combustion technique from stoichiometric amount of zirconyl nitrate and urea. The nitrate combustion route produces crystalline zirconia. Zirconia nanoparticles were grown inside alumina templates to control the crystal size. The alumina templates were characterized by pores of sizes of approximately 6-8 nm as observed from electron microscope photographs. The SEM micrographs show flake-like appearance of the α-Al2O3 particles with approximate sizes of 0.5 μm or less. Further, the particles have approximately hexagonal morphology. The X-ray diffraction pattern of the as-prepared α-Al2O3 sample shows crystalline nature. X-ray diffraction line profile analysis using Williamson–Hall method and more rigorous Fourier method of Warren and Averbach reveals that the alumina templates are characterized by negligible defect-related effect of lattice distortion. The amount of lattice microstrain ranges between 0.0004 and 0.0007 depending on the method of analysis. Rietveld structure refinement using Structure-Microstructure Refinement software MAUD did not reveal any gross difference with the literature reported values for cell parameters a and c and fractional atomic coordinates x and z for Al and O atoms indicating no large-scale bond deformation. The Williamson–Hall plot is nonlinear in nature. The zirconia nanoparticles inside the pores of alumina templates are characterized by tetragonal crystal structure which is a unique example of size-stabilized zirconia. The template X-ray reflections are skewed in nature which indicates some distortion of the templates might have taken place. The distortion is, however, plastic in nature which is evident from the higher level of lattice distortion viz 0.2% of lattice microstrain. It is hence clear that the zirconia particles have grown inside the pores of the alumina templates, and the difference of thermal expansion coefficients of alumina and zirconia might have introduced residual stresses in the alumina matrix. The size of zirconia nanoparticles is ~ 40 nm which is slightly higher than that required for size stabilization. Structure refinement reveals a large amount of oxygen deficiency. Thus, it may be argued that size-stabilized zirconia is an oxygen deficient form.

References

Kisi, E.H., Howard, C.J.: Crystal structures of zirconia phases and their inter-relation. Key Eng. Mat. 153–154, 1–36 (1998)

Shelef, M., McCabe, R.W.: Twenty-five years after introduction of automotive catalysts: What next? Catal. Today 62(1), 35–50 (2000)

Kašpar, J., Fornasiero, P., Hickey, N.: Automotive catalytic converters: current status and some perspectives. Catal. Today 77(4), 419–449 (2003)

El-Sharkawy, E.A., Khder, A.S., Ahmed, A.I.: Structural characterization and catalytic activity of molybdenum oxide supported zirconia catalysts. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 102(1–3), 128–137 (2007)

Chary, K.V.R., Reddy, K.R., Kishan, G., Niemantsverdriet, J.W., Mestl, G.: Structure and catalytic properties of molybdenum oxide catalysts supported on zirconia. J. Catal. 226(2), 283–291 (2004)

Porter, D.L., Heuer, A.H.: Microstructural development in MgO-partially stabilized zirconia (Mg-PSZ). J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 62(5–6), 298–305 (1979)

Garvie, R.C., Hannink, R.H.J., Urbani, C.: Fracture mechanics study of a transformation toughened zirconia alloy in the CaO–ZrO2 system. Ceramurgia Int. 6(1), 19–24 (1980)

Scott, H.G.: Phase relationships in the zirconia-yttria system. J. Mater. Sci. 10(9), 1527–1535 (1975)

Toraya, H.: Effect of YO1.5 dopant on unit-cell parameters of ZrO2 at low contents of YO1.5. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 72(4), 662–664 (1989)

Sorensen, B.F., Kumar, A.N.: Fracture resistance of 8 mol% yttria stabilized zirconia. Bull. Mater. Sci. 24(2), 111–116 (2001)

Yashima, M., Sasaki, S., Kakihana, M., Yoshimura, M.: Raman scattering study of cubic-tetragonal phase transition in Zr1−xCexO2 solid solution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 77(4), 1067–1071 (1994)

Warren, B.E.: X-ray Diffraction. Addison-Wesley, New York (1969)

Klug, H.P., Alexander, L.E.: X-ray Diffraction Procedures. Wiley, New York (1974)

Langford, J.I.: Rapid method for analysing the breadths of diffraction and spectral lines using the Voigt function. J. Appl. Cryst. 11(1), 10–14 (1978)

de Keijser, ThH, Langford, J.I., Mittemeijer, E.J., Vogels, A.B.P.: Use of the Voigt function in a single-line method for the analysis of X-ray diffraction line broadening. J. Appl. Cryst. 15(3), 308–314 (1982)

Schoening, F.R.L.: Strain and particle size values from X-ray line breadths. Acta. Cryst. 18, 975–976 (1965)

Williamson, G.K., Hall, W.H.: X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram. Acta Metall. 1(1), 22–31 (1953)

Halder, N.C., Wagner, C.N.J.: Separation of particle size and lattice strain in integral breadth measurements. Acta Cryst. 20, 312–313 (1966)

Bertaut, E.F.: Debye–Scherrer lines and size distribution of Bragg domains in polycrystalline powders. Acta Cryst. 3, 14–18 (1950)

Stokes, A.R.: A numerical Fourier-analysis method for the correction of widths and shapes of lines on X-ray powder photographs. Proc. Phys. Soc. Lond. 61(4), 382–391 (1948)

Enzo, S., Fagherazzi, G., Benedetti, A., Polizzi, S.: A profile-fitting procedure for analysis of broadened X-ray diffraction peaks. I. Methodology. J. Appl. Cryst. 21, 536–542 (1988)

Lutterotti, L., Scardi, P.: Simultaneous structure and size-strain refinement by the Rietveld method. J. Appl. Cryst. 23, 246–252 (1990)

Pawley, G.S.: Unit-cell refinement from powder diffraction scans. J. Appl. Cryst. 14, 357–361 (1981)

Thompson, P., Cox, D.E., Hastings, J.B.: Rietveld refinement of Debye–Scherrer synchrotron X-ray data from A12O3. J. Appl. Cryst. 20, 79–83 (1987)

Young, R.A.: The Rietveld method. In: Young, R.A. (ed.) The Rietveld method, pp. 1–38. Oxford University Press, Washington DC (1996)

Hill, R.J.: Calculated X-ray powder diffraction data for phases encountered in lead/acid battery plates. J. Powd. Sour. 9(1), 55–71 (1983)

Hill, R.J., Howard, C.J.: Quantitative phase analysis from neutron powder diffraction data using the Rietveid method. J. Appl. Cryst. 20, 467–474 (1987)

Garvie, R.C.: Stabilization of the tetragonal structure in zirconia microcrystals. J. Phys. Chem. 82(2), 218–224 (1978)

Aruna, S.T., Mukasyan, A.S.: Combustion synthesis and nanomaterials. Curr. Opin. Sol. State Mater. Sci. 12(3–4), 44–50 (2008)

Kingsley, J.J., Patil, K.C.: A novel combustion process for the synthesis of fine particle α-alumina and related oxide materials. Mater. Lett. 6(11–12), 427–432 (1988)

van Berkum, J.G.M., Sprong, G.J.M., de Keijser, ThH, Delhez, R., Sonneveld, E.J.: The optimum standard specimen for X-ray diffraction line-profile analysis. Powd. Diffr. 10(2), 129–139 (1995)

Lutterotti, L.: MAUD Version 2.71, http://maud.radiographema.com/(2016). Accessed 5 Nov 2017

Caglioti, G., Paoletti, A., Ricci, F.P.: Choice of collimators for a crystal spectrometer for neutron diffraction. Nucl. Instrum. 3(4), 223–228 (1958)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Deb, A.K., Chatterjee, P. Estimation of lattice strain in alumina–zirconia nanocomposites by X-ray diffraction peak profile analysis. J Theor Appl Phys 13, 221–229 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-019-0338-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-019-0338-z