Abstract

An experimental study has been conducted to study the cyclic behavior of reinforced concrete beams in which steel fibers were added to the concrete mix. Seven similar geometrically specimens in full scale were studied under four- point bending test in the form of slow cyclic loading. One sample as a control specimen was made without steel fibers or 0% volume fraction (vf) and six other samples with 1, 2 and 4% vf of steel fibers in twin models. The maximum and ultimate resistance, ductility, degradation of loading and unloading stiffness, absorption and dissipation of energy and equivalent viscous damping were studied in this investigation and the effect of steel fibers on the cyclic behavior was compared with each other. Generally, the addition of steel fibers up to a certain limit value (vf = 2%) improves the cyclic behavior of reinforced concrete beams and results in the increase of maximum strength and ultimate displacement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The idea of adding the fibers to brittle materials to increase ductility goes back to old times (Felekoĝlu et al. 2007). In ancient Egypt, straw was added to mud brick. Nowadays, various types of fiber are used; for example, in concrete structures the most popular is steel fiber. Many researches have been conducted on steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) (Sahoo et al. 2016, 2015a, b; Ozcan et al. 2009; Nataraja et al. 1999; Vandewalle et al. 2003; Ganesan et al. 2007). Reinforcing of concrete with steel fibers has some advantages such as decrease and control of cracking, increase of durability and age of concrete, increase of ductility, toughness, tensile, flexural and shear strength of concrete, and some disadvantages such as corrosion of fibers, decrease of workability of concrete, irregularity of distribution and accumulation around the local area. The fibers differ in size and shape such as straight, hooked and corrugated (Wang 2006). It has been shown that steel fibers with low volume fraction (< 1%), in SFRC, have a nonsignificant effect on compressive strength, but improve splitting tensile and flexural strength and toughness (Sahoo and Kumar 2015; Holschemacher et al. 2010; Mohod 2012). Cho and Kim (2003) showed that the addition of steel fibers to concrete beams enhanced the initial stiffness and ultimate strength and also the ductility in specimens that failed in shear–flexural and flexural are more than those which failed dominantly in shear. The results show that the end-hooked fiber types lead to more residual load-bearing capacity for high deformation in four-point bending test, but corrugated fibers lead to high load-bearing capacity for lower deformation and there is a decrease of capacity with increasing deflection (Holschemacher and Muller 2007).

Nataraja et al. (1999) presented stress–strain curves for steel fiber-reinforced concrete under compression loading. In their studies, equations are also proposed to quantify the effect of fiber on compressive strength, strain at peak stress and the toughness of concrete in terms of the fiber-reinforcing parameter.

Casanova and Rossi (1997) studied the behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams. In their studies, uniaxial tensile test was used to achieve the post-cracking relationship which leads to the definition of a characteristic stress versus crack opening. By using fibers in concrete, the post-crack softening behavior could be changed to hardening behavior. Post-crack hardening allows multiple cracks before failure, while in post-crack softening there is a reduction of strength after the first crack not allowing further cracks.

The experimental study of fiber-reinforced concrete under cyclic compressive loading shows that its behavior is very similar to plain concrete or concrete confined by steel spirals, indicating that the fibers primarily influence the envelope curve (Otter and Naaman 1988).

The cyclic response of non-ductile reinforced concrete frame was studied by Oinman et al. (2014). They showed that the addition of steel fibers in the critical location of beam–column joints enhanced the lateral load resistance capacity and corresponding lateral drift. Also, the lateral stiffness increased and degradation of the lateral stiffness occurred at a high level of drift. There is no significant difference in energy absorption between specimens with and without steel fibers. Due to significant damages observed in the columns of model without steel fibers, a higher damping was observed as compared to the SFRC.

Biolzi and Cattaneo (2017) studied the shear–flexural response of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams with longitudinal and transverse reinforcement under four- point bending test in the form of monotonic behavior. They showed that the inclusion of steel fibers in concrete beams causes an important increase in shear and bending strength and also ductility and stiffness. Beams failed due to the crushing of the compressive zone in a ductile manner, showing the yielding of the longitudinal reinforcement. In beams with steel fibers, one main crack was usually localized in the central part of the beam.

Sahoo and Sharma (2014) showed that the addition of steel fibers enhanced the flexural and shear strengths and the ductility of the flexural members. The addition of a minimum of 0.5% fiber content in the beams with shear stirrups changed the mode of failure from brittle to ductile, whereas a minimum fiber content of 1.0% is required to achieve the ductile response of the beams without shear stirrups.

In this paper, the cyclic behavior of reinforced concrete beams with addition of steel fibers in the concrete mix is studied by experimental modeling. The emphasis of this investigation is to study the cyclic behavior of full-scale reinforced concrete beams with longitudinal and transverse reinforcement bars. Seven full-scale specimens with 0, 1, 2 and 4% volume fraction (vf) of steel fibers were studied under the four-point bending test in the form of slow cyclic loading. Some important parameters of specimens such as cyclic response, capacity curve, ductility and ultimate displacement, stiffness of loading and unloading with propagation of damage, absorption and energy dissipation and equivalent viscous damping were studied due to the influence of steel fibers on the cyclic behavior of samples.

Experimental investigation

The details of specimens, materials, setup of samples and imposed loading history are presented in the following sections.

Materials and specimens

Seven reinforced beams of concrete mix with 0, 1, 2 and 4% volume fraction of steel fibers were fabricated in the laboratory of Semnan University. One sample was without steel fibers and the rest of the samples were twin models with the same property because of the probable scatter of results. The shape of the fibers is hooked and the size of the fibers is 60 and 0.8 mm in length and diameter, respectively. The mechanical properties of the fibers in the experimental test are presented in Table 1.

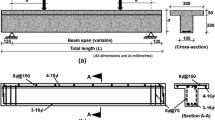

The dimensions of the specimens are 2300 mm and 250*250 mm2 in length and cross section, respectively. The top and bottom longitudinal and transverse armatures are 3Φ10 and Φ8@150 mm, respectively. The corresponding yield strength is 4000 and 3000 kg/cm2, respectively. Figure 1 shows the details of the specimens. The length of the cover to concrete is 50 mm.

Portland cement type II was used in the concrete mix and liquid polycarboxylate super- plasticizer, due to increase of workability, and micro silica, due to modification of physical properties of concrete, were added to the concrete mix. The mix design of concrete for each specimen is presented in Table 2 (the values are in kg).

Three cube compressive strength tests (15 × 15 × 15 cm3 and 28 days) were conducted to measure the compressive strength of concrete. The compression strength of concrete with 0, 1 and 2% vf of steel fibers are 34.69, 36.18 and 24.17 MPa, respectively. Similarly, it is observed in other published test results that the addition of fibers does not significantly affect the compressive strength of concrete. (Mohod 2012; Bencardino et al. 2008).

Setup of experimental models

Four- point bending test in the form of slow cyclic loading was conducted by two hydraulic actuators at the top and bottom of the simple support specimens. The segments which impose the force at 0.25 length of the beams were located at the top and bottom of the beams and anchored to each other by eight studs. The equipment of the setup of the experimental models consist of: reaction frame, two hydraulic actuators with 250 kN capacity and 30 cm of maximum displacement at the top and bottom of the specimen, two load cells for the measurement of load, two LVDTs for the measurement of displacement at the midspan of the specimen. The schematic shape of the setup of the experimental models is shown in Fig. 2.

Imposed loading history

Displacement-controlled cyclic loading is imposed on test specimens. Each cycle is repeated twice and the first cycle is initiated ± 1 mm and the second cycle increased to ± 2 mm and other cycles increased to ± 2 mm in each cycle until ± 30 mm (Fig. 3).

Items of investigation

The obtained results in the experimental models are presented in this section. The hysteretic behavior of specimens which clarifies their nonlinear behavior, capacity curve, maximum and ultimate strength, ductility and ultimate displacement, absorption and dissipation energy, damping and deterioration of stiffness are studied in this investigation. These results are compared between specimens with and without steel fibers to identify the influence of steel fibers on the cyclic behavior of reinforced concrete beams and also the effect of value of vf of steel fibers on the items of this investigation.

Hysteretic behavior

The hysteretic behavior is shown in the form of load from the top and bottom actuator versus displacement at midspan of specimens. Figure 4 shows the cyclic response and fracture mechanism of specimens.

The cracking pattern was studied in SFRC with stirrups by Biolzi and Cattaneo (2017). Beams without steel fibers were characterized concrete crushing in the compressive zone and a large number of cracks with branching led to failure, but in beams with steel fibers one main crack was usually localized in the central part of the beam (Fig. 5).

Typical crack patterns: a without steel fibers, b with steel fibers (Biolzi and Cattaneo 2017)

According to Fig. 4, with increasing steel fibers in the concrete mix, maximum strength and ultimate displacement increase and the extension of damage and propagation of cracking in the total length of the specimen without steel fiber are larger than in specimens with steel fibers. Also, one main crack was localized in the central part of the specimens with steel fibers. The failure mechanism of specimens is in agreement with studies of Biolzi and Cattaneo (2017).

Figure 6 shows the comparison of the capacity curves resulting from hysteretic curves. These curves were derived based on the mean values and evaluation of the results of specimens. Also in the positive range of loading, the value of maximum strength and ultimate displacement are presented in Table 3.

According to Fig. 6, in the positive range of loading by increasing vf. of steel fibers up to 2%, the maximum strength and ultimate displacement increase; in contrast to using 4% steel fibers, these values did not change compared to 2% of steel fibers. It seems by increasing steel fibers to 4%, the efficiency of the concrete mix decreases. This limitation in the negative range is 1%. It seems the optimum value of steel fibers in the concrete mix is 1–2%.

Using idealized tree linear force displacement curve of specimens based on significant change in stiffness to define elastic stiffness and yield displacement (y) and also strength drop to 20% from the maximum attained strength as ultimate strength, it is easier to compare the capacity curve of specimens (Fig. 7 and Table 4). Generally, by increasing steel fiber maximum strength, maximum displacement and ultimate strength increase.

Secant stiffness

In this section, the effect of steel fibers on the secant stiffness in loading and unloading is studied. The value of this parameter and its changes is the index of damage in the specimens. The secant stiffness was studied in the positive range of loading for specimens with various vf of steel fibers. This stiffness is described as in Fig. 8. This stiffness is the slope of the line joining the origin of loading to the peak load of the positive cycle.

By defining displacement corresponding to the peak load in each cycle (u), and displacement corresponding to elastic limit (y), it is possible to introduce the ductility factor as μ = u/y. Figure 9 presents the secant stiffness versus ductility factor.

It is seen that by increasing vf of steel fibers, the secant stiffness increases at the identical ductility factor and the rate of decrease of stiffness is slower at higher values of ductility. Also, the residual stiffness at the higher value of ductility is more with increasing vf. of steel fibers. The empirical equation for secant stiffness is developed by nonlinear regression data. The equation of ksec = aµb is introduced, in which ksec and µ are secant stiffness and ductility, respectively, and a and b are parameters which depend on the value of vf of steel fibers. Table 5 shows the values of a and b corresponding to vf of steel fibers and R2 is the coefficient correlation.

One of the parameters of damage criteria in hysteretic behavior is the stiffness of unloading with progression of damage. To evaluate this factor, the ratio of stiffness of unloading to loading (initial stiffness) is studied in this section. The relation of \(\frac{{k_{\upmu} }}{{k_{\text{i}} }} = \mu^{ - \beta }\) is introduced in which \(k_{\upmu}\) and Ki are the stiffness of unloading corresponding to ductility and initial stiffness, respectively. The parameter of \(\beta\) is the factor to introduce damage in the specimens, so in the case of larger value of this parameter the damage is more. Table 6 shows the values of \(\beta\) corresponding to vf of steel fibers and R2 is the coefficient correlation presented in this table. Also, Fig. 10 shows the ratio of stiffness of unloading to initial stiffness versus ductility factor. It is obvious that with increase of the steel fibers, the damage and the factor of \(\beta\) decrease.

Absorption and dissipation energy and damping

The seismic resistance of structure depends on the absorption and dissipation of seismic energy. The dissipated energy is measured by area under the hysteresis loop and by increasing this value, the absorption of seismic energy and transformation of that to hysteresis energy increase. In this section, the value of hysteresis energy versus displacement of specimens is compared with each other (Fig. 11). Generally, there is no significant difference between hysteresis energy at smaller displacement, but at larger displacement the value of hysteresis energy increases due to addition of steel fibers. The specimen with vf of 1% shows an increase of about 75% in energy dissipation as compared to the specimen with vf 0%, but this value is less for vf of 2 and 4%. It seems by increasing vf of steel fibers by more than 1%, there is no significant difference in the value of hysteresis energy compared with vf of 1%.

One of the methods for identifying damping due to nonlinear behavior of structures is equivalent viscous damping. The most common method for defining equivalent viscous damping resulting from hysteretic damping is to equate the energy dissipated in a vibration cycle of the inelastic system and the equivalent linear system (Dwairi et al. 2007). It can be shown that the equivalent viscous damping ratio is:

where ED is the energy dissipated in the inelastic system given by the area enclosed by the hysteresis loop and \(E_{\text{S}}\) is the strain energy of the equivalent linear system with stiffness ksec (Fig. 12).

In the present study, equivalent damping is the sum of the elastic and hysteretic damping expressed in Eq. (2) as:

where \(\xi_{\text{el}}\) is 5% and \(\xi_{\text{hyst}}\) is determined by Eq. (1). Figure 13 shows the comparison of equivalent viscous damping versus displacement. As shown, the equivalent viscous damping for specimen with vf 0% at larger displacement is higher in comparison with specimens with steel fibers, but at smaller displacement there is no significant difference between them. This is due to significant damage in specimen without steel fibers. Figures 9 and 10 show decrease in secant stiffness in specimen without steel fibers, in comparison with other specimens. This could result in decrease of strain energy and increase of equivalent viscous damping.

Discussion

According to the results of experimental models, all of them fail in the flexural mode. However, the addition of steel fibers to concrete results in the concentration of damage at the zone of maximum displacement of specimens, whereas in the specimen without steel fibers the cracks spread in the total length of the beam and finally the model fails at the zone of imposed force. The steel fibers bridge the microcracks and prevent their opening. At the midspan by increasing displacement, the steel fibers in the mouth of the crack elongate, yield and finally tear at the ultimate state of the beams. This mechanism results in the increase of capacity of ultimate load and displacement but it seems by increasing the content of fibers from 2 to 4% the efficiency of steel fibers is affectless, it can relate to the reduction of workability of concrete and local behavior of concrete. Reinforcing concrete with steel fibers does not affect the stiffness considerably, but the stability of models in loading and unloading increases. As expected, by the addition of steel fibers to the concrete mix, the absorption and dissipation of energy increase, but because of the limitation of damage at the length of the specimens the viscous damping decreases.

Conclusions

In this experimental investigation, the effect of steel fibers is studied on the cyclic behavior of reinforced concrete beams.

-

1.

Generally with increasing steel fibers, the maximum strength and displacement increase, although this increment has limitation with the volume fraction of steel fibers.

-

2.

It seems with volume fraction of steel fibers, more than 2% of the efficiency of the concrete mix decreases and the maximum strength could be decreased.

-

3.

By addition of steel fibers to the concrete mix, the main crack is localized in the central part of the beams and the number of cracks is less in comparison with the specimen without steel fiber.

-

4.

Generally with increasing volume fraction of steel fibers, the secant stiffness in loading and unloading increases. In other words, with increasing steel fibers in the concrete mix, damage in the specimen decreases and the cyclic behavior is more stable in comparison with specimens without steel fibers or less volume fraction of steel fibers.

-

5.

At smaller displacement, there is no significant difference between the hysteresis energy of specimens. For larger displacement, this difference is considerable, but with increase of steel fibers more than 1% of the difference decreases.

-

6.

At smaller displacement, there is no significant difference between the equivalent viscous damping of specimens. At larger displacement, the equivalent viscous damping of specimen without steel fibers is higher than specimen with steel fibers. More damage before failure in the specimen without steel fibers can result in higher value of equivalent viscous damping.

References

Bencardino F, Rizzuti L, Spadea G, Swamy R (2008) Stress–strain behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete in compression. J Mater Civil Eng 20:255–263

Biolzi L, Cattaneo S (2017) Response of steel fiber reinforced high strength concrete beams: experiments and code predictions. J Cem Concr Compos 77:1–13

Casanova P, Rossi P (1997) Analysis and design of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams. ACI Mater J 94(5):595–602

Cho SH, Kim YI (2003) Effects of steel fibers on short beams loaded in shear. ACI Struct J 100(6):765–774

Dwairi HM, Kowalsky MJ, Nau JM (2007) Equivalent damping in support of direct displacement-based design. J Earthq Eng 11(4):512–530

Felekoĝlu SB, Turkel UK, Altuntas Y (2007) Effects of steel fiber reinforcement on surface wear resistance of self-compacting repair mortars. Department of Civil Engineering, Dokuz Eylu¨ l University, 35160 Izmir, Turkey

Ganesan N, Indira PV, Abraham R (2007) Steel fiber reinforced high performance concrete beam-column joints subjected to cyclic loading. ISET J Earthq Technol Tech Note 44(3–4):445–456

Holschemacher K, Muller T (2007) Influence of fiber type and concrete composition on properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete. International conference on advanced in cement based material and application in civil infrastructure (ACBM-ACI), Lahore, Pakistan, pp 633–642

Holschemacher K, Mueller T, Ribakov Y (2010) Effect of steel fibers on mechanical properties of high-strength concrete. J Mater Des 31(5):2604–2615

Mohod MV (2012) Performance of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Int J Eng Sci 1(12):1–4

Nataraja MC, Dhang N, Gupta AP (1999) Stress–strain curves for steel-fiber reinforced concrete under Compression. J Cem Concr Compos 21(5–6):383–390

Oinman RM, Sahoo D, Sindhu R (2014) Cyclic Response of non-ductile RC frame with steel fibers at beam-column joints and plastic hinge regions. J Earthq Eng 18(6):908–928

Otter DE, Naaman AE (1988) Properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete under cyclic loading. Mater J 85:254–261

Ozcan M, Bayraktar A, Sahin A, Haktanir T, Turker T (2009) Experimental and finite element analysis on steel fiber-reinforced concrete(SFRC) beams ultimate behavior. Constr Build Mater 23:1064–1077

Sahoo DR, Kumar N (2015) Monotonic behavior of large-scale SFRC beams without stirrups. Eng Struct 92:46–54

Sahoo DR, Sharma A (2014) Effect of steel fiber content on behavior on concrete beams with and without shear stirrups. ACI Struct J 111(5):1157–1166

Sahoo DR, Solanki A, Kumar A (2015a) Influence of steel and polypropylene fibers on flexural behavior of RC beams. ASCE J Mater Civil Eng 27(8):04014232

Sahoo DR, Maran K, Kumar A (2015b) Effect of steel and synthetic fibers on shear strength of RC beams without shear stirrups. Constr Build Mater 83:150–158

Sahoo DR, Bhagat S, Reddy TCV (2016) Experimental investigation of shear-span to effective-depth ratio for steel fiber reinforced concrete T-beams. Mater Struct 49(9):3815–3830

Vandewalle L et al (2003) Recommendations of RILEM TC 162-TDF: test and design methods for steel fiber reinforced concrete (final recommendation). Mater Struct 36:560–567

Wang C (2006) Experimental investigation on behavior of steel fibers reinforced concrete. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to urisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranjbaran, F., Rezayfar, O. & Mirzababai, R. Experimental investigation of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams under cyclic loading. Int J Adv Struct Eng 10, 49–60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40091-018-0177-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40091-018-0177-1