Abstract

The present study used modified nanofiltration (NF) membranes to remove the emerging contaminant of amoxicillin (AMX) from synthetic wastewater. For this purpose, Merpol surfactant and polyvinylpyrrolidone were added to the casting solutions to prepare flat sheet asymmetric polyethersulfone (PES) NF membranes through phase inversion process. Then, the effect of adding Merpol surfactant at different concentrations on the morphology, hydrophilicity, and pure water flux (PWF) of the membranes, as well as the separation of AMX from aqueous solutions was investigated. The characteristics of the prepared membranes were studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), contact angle (CA) measurement and performance tests. The obtained results approved the improved hydrophilicity of the PES membranes after adding Merpol surfactant to the casting solution. The findings also revealed a gradual increase in the average size of the membrane pores in sub-layer and thinner top layer, proportional to the increase of surfactant content in the solution. The results also confirmed the increase of PWF under the influence of surfactant increase. As a result, for the membrane containing 8 wt% Merpol additive, the lowest CA (52.08°), the highest PWF (76.31 L/m2 h), and maximum AMX excretion (97%) were achieved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Membrane separation technology has been widely applied in various industries because of its advantages, such as low energy consumption, no phase transition, and easy to scale up [1, 2]. This technology is a promising solution for removal of the emerging contaminants [3].

Nanofiltration (NF) membranes have a selectivity capability in the region between reverse osmosis (RO) and ultrafiltration (UF), which make it possible to separate monovalent and divalent salts, as well as organic solutes with molecular weights up to 1000 g/mol [4]. The use of this relatively new technology has grown steadily in recent years [5, 6]. This is mainly due to low energy consumption and the high efficiency of this separation technology, which has led to its widespread use in various industries, such as water softening, drinking-water purification, dye and antibiotic purification, salt removal, and waste treatment [7]. Nanofiltration is also increasingly used in new water treatment programs. In addition, to have highly biologically stable water, NF membranes offer a very good removal of the organic micropollutants. The reason is that the molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) values of NF membranes are often in the same range as that of endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) and personal care products (PPCPs) [8, 9].

Polymeric membranes, which occupy the vast majority of the market for water treatment, suffer significantly from fouling [10]. Fouling on the membrane surfaces has been regarded as the most serious problem on membrane filtration technologies [11].

Polyethersulfone (PES), due to its high chemical, thermal, and mechanical stability, has widely been used to synthesis membranes for a variety of applications [12]. The main limiting factor for using this chemical compound is its low hydrophilicity, which increases membrane fouling [13, 14].

One way to modify the performance of PES nanofiltration membranes is to increase their hydrophilicity. So far, the impact of the increased hydrophilicity of the membrane surfaces and pore walls on the reduction or suppression of membrane fouling has been confirmed by many scholars around the world in recent years [15]. Adding hydrophilic polymer additives, such as polymeric surfactants, to PES membranes is a widely accepted way to improve hydrophilicity of the membranes. Surfactants are surface-active agents, constituting the most important category of detergents [16]. For this purpose, various surfactants have yet been introduced, including but not limited to, Pluronic F127 [17], Tween 80 [18], Tween 20 [15], Tetronic 1307 [12], Triton X100, CTAB and SDS [19], Brij S100 [20] and Brij58 [21, 22].

Antibiotics have become emerging contaminants of aquatic ecosystems in recent years. These pollutants, even in small quantities, are dangerous due to their high persistence in aquatic ecosystems. Studies have revealed the inefficiencies of conventional wastewater treatment methods in eliminating this pollutant, as evidence of presenting antibiotic contaminants in natural environments have been reported from almost every corner of the world [23, 24]. The presence of such compounds in natural environments has raised concerns about their toxicity to humans and animals, as well as the emergence of bacteria and genes resistant to antibiotics [25, 26]. Nowadays, membrane filtration based on NF and RO membranes can be considered one of the most promising techniques known to remove antibiotic compounds [27]. There are numerous studies that have confirmed the effectiveness of this approach in eliminating antibiotic compounds, such as amoxicillin (AMX). As such, Zazouli et al. [28] used two commercial NF membranes, namely SR2 and SR3, to compare their performance in rejection of AMX. According to their findings, the SR3 NF membranes had a better performance than SR2 in the removal of AMX. They reported a removal rate of 95% for SR3 NF membranes and 64.9% for SR2 NF membranes. In another study by Shahtalebi et al. [29], the performance of commercial NF4040 membrane in AMX removal was estimated to be 97%. Their results showed that the AMX content of the feed stream is an influential factor in the rejection of AMX antibiotics so that the removal efficiency will be lower at higher concentrations.

There is no previously published article regarding the effects of the addition of Merpol surfactant as hydrophilic additive on the fundamental characteristics of the PES nanofiltration membranes to remove antibiotics, such as AMX. Thus, in this study, the effect of adding this surfactant into the PES casting solution on the morphology, hydrophilicity, and pure water flux (PWF) of the membranes as well as the rejection of AMX was investigated in detail.

Chemicals and methods

Chemicals

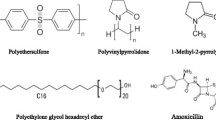

In this study, PES was bought from BASF Corporation, a German producer of chemicals. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP 40) was applied as a pore former and “MERPOL®HCS” was a nonionic surfactant additive, supplied from Aldrich Co. The solvent was 1-methyl-2pyrrolidone (NMP), with an analytical purity of 99.5%. Distilled water was the nonsolvent agent used in this research. Amoxicillin was also prepared from Dana pharmaceutical Co. in Tabriz, Iran. Other chemicals along with more information on the used materials are summarized in Table 1. Moreover, the molecular structure of PES, Merpol, PVP 40, NMP, and AMX is shown in Fig. 1.

Membrane preparation

Homogeneous solutions containing PES polymer, NMP solvent, PVP as invariable additive (pore former) and the specific amount of Merpol surfactant (0–8 wt%) as variant additive were prepared by stirring (200 rpm) for 12 h at ambient temperature (25 ± 2 °C). The dope solutions were held at ambient temperature for almost 12 h to remove air bubbles. The solutions were cast onto a glass plate with a film applicator. Then they were immersed in a distilled water bath (0 °C) for 12 h to complete the phase separation where exchange between the solvent and nonsolvent was induced. For drying the membranes, they were kept between two sheets of filter paper for 24 h [21]. The prepared PES compositions are shown in Table 2.

A film applicator was used to caste the prepared homogenous solution on a glass substrate to a thickness of 300 µm. Then the cast film was moved into the non-solvent bath for immersion precipitation at 0 °C temperature, for 24 h to complete the phase separation, where exchange between the solvent (NMP) and non-solvent (water) was induced. This was done to ensure complete removal or evaporation of the residual solvent from the membranes. In the end, the membranes were dried up by filter papers for 24 h at room temperature.

Membrane characterization

Measurement of contact angle

Calculation of water-membrane contact angle (CA) is necessary for evaluating the hydrophilic feature of the membranes. In this research, this parameter was measured directly by the CA instrument of G10 KRUSS type, made in Germany. It should be mentioned that in all measuring steps, distilled water was used as probe liquid.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Cross-sections of the membrane were prepared for careful examination by the scanning electron microscope (SEM), of KYKY-EM 3200 type, made in China. Once the membrane specimens were frozen by liquid nitrogen, they were fractured and sputter-coated with gold. Finally, the specimens were examined by SEM at 25 kV.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

The surface morphologies of the membranes were observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Hitachi S4800, Japan). Before FESEM analysis, the membrane samples were dehydrated through graded ethanol series and dried in vacuum oven adequately.

Membrane performance measurement

Pure water flux (PWF)

To check the performance of the prepared membranes, a lab-scale cross-flow system was used. The system was mainly comprised of a reservoir, a pump, and a membrane module. The study was performed in batch mode at a trans-membrane pressure of 10 bars. To estimate PWF, permeate was collected constantly in a measuring cylinder over certain intervals. The details of the experimental set-up and calculation of PWF have been described elsewhere [30].

AMX rejection

The filtration experiments were conducted to investigate capability of the prepared PES membranes in the rejection of AMX antibiotics. The dissolution of the AMX antibiotic in distilled water was the first step in this experiment.

For this purpose, the AMX was dissolved in distilled water and its concentration was kept constant at 20 ppm. The experiments were conducted under trans-membrane pressure of 10 bars. the feed, permeate, and retentate streams were sampled to check their AMX content by means of UV–Vis spectrophotometer (T60, China) at λmax 660 nm [31]. Accordingly, the amount of AMX removal was calculated in percent.

Results and discussion

Membrane morphology

Figures 2 and 3, respectively, demonstrates the cross-section SEM and top surface FESEM images taken from the prepared membranes in two magnification scales.

As Fig. 2 suggests, the top layer structure shows a completely different structure depending on the amount of the surfactant present in the casting solution. Changes in the contents of the Merpol surfactant caused morphological changes in the membrane structures so that by increasing the amount of surfactant from 0 to 8 wt%, the thick and dense upper layer of the membrane was converted into a low-dense thin layer. However, the further increase of surfactant from 8 to 10 wt% had inverse effects and thickened the surface layer. The mechanism of membrane formation has already been described in previous studies, such as Saljoughi and Mousavi [32] and Saljoughi et al. [33,34,35]. In general, the addition of hydrophilic additives, such as Merpol, to the casting solution has two main effects on membrane morphology, which are discussed below in brief.

As a hydrophilic additive with nonsolvent properties, Merpol causes an increase in the thermodynamic instability of the casting solution. Once the cast films are immersed into the coagulation bath, the film surface will be coated by a layer of amphiphilic Merpol molecules. The presence of these molecules will reduce surface tension and, consequently, water molecules will be diffused, easily [30, 32]. Low affinity between PES and water molecules causes the formation of nuclei of a polymer-poor phase on the surface, which ultimately causes the repulsion of PES chains at the presence of surfactant molecules. These nuclei are surface porous builders. As long as the concentration of the polymer in the boundaries rises significantly and until the moment of solidification, the process of solvent and nonsolvent diffusional exchange will continue. This suggests that the addition of Merpol leads to the formation of more nuclei, resulting in more porosity in the surface (Fig. 3). The instantaneous demixing in the coagulation bath and the formation of more porous membrane structure is a clear consequence of the above effects.

Another important effect of Merpol is the increase in viscosity of the cast film. This increase in viscosity, during the solidification process, reduces solvent (NMP) and nonsolvent (water) diffusional exchange rate and prevents instantaneous demixing. The delayed demixing process suppresses macrovides and creates denser structures. What ultimately determines the characteristics of the membrane’s final structure depends on the priority of instantaneous or delayed demixing processes which in turn as discussed earlier depends on the concentration of Merpol surfactant in the cast solution.

Two key factors involved in the formation of thick and low porosity membrane structures, which include increased viscosity and priority of delayed demixing over instantaneous. This condition, in the present study, was observed when the surfactant content was increased from 8 to 10 wt%.

Membrane contact angle (CA)

Table 3 shows the effect of adding Merpol surfactant on the CA and wettability of the PES membranes. As seen in Table 3, the modified PES membranes have a smaller CA and consequently, a higher hydrophilic property than pure membranes. This may attribute to the presence of Merpol surfactant as hydrophilic additives in the modified membranes. Moreover, the molecular weight of the Merpol is high and this prevents its complete and convenient washing during membrane formation [36]. The amount of residual Merpol that somehow reflects the hydrophilicity degree of the membrane depends strongly on the initial amount of this surfactant in the casting solution. The CA of the membrane, containing 10 wt% Merpol, is more than the membrane with the lower surfactant content (8 wt% Merpol). This could be explained by the lower porosity of the membrane surface [21].

Membrane performance in removal of AMX

Figure 4 shows different amounts of the AMX antibiotic rejection in the presence of different surfactant contents.

All the membranes made with different amounts of Merpol surfactant have a better performance in antibiotic rejection than pure the membrane. As the surfactant is added to the casting solution, the membrane performance in the elimination of AMX antibiotic becomes better until it reaches its peak of 97% at 8 wt% Merpol content. Exceeding this amount, any further increase in the surfactant content does not lead to a positive effect on the AMX rejection performance; it even causes a performance loss. The mechanisms such as size exclusion, electrostatic charge repulsion, and adsorption, help to retain the organic solutes by NF membranes [4, 37]. The relatively hydrophilic nature of some pharmaceutical compounds such as antibiotics [38] prevents them from absorption by the surface of membranes.

As a result, the rejection of AMX can take place by steady-state rejection due to steric effects for uncharged solutes and integrated steric and electrostatic effects for charged solutes [21, 39]. In retention of pharmaceuticals by tight NF membranes, Stearic effects are dominant, while in loose NF membranes, both electrostatic repulsion and steric exclusion control the retention of ionizable pharmaceuticals [40].

Another important factor affecting the performance of membranes is the morphological changes that occur due to the addition of surfactants. Water molecules are much smaller than AMX molecules. According to Fig. 2, the pure membrane (free of Merpol surfactant) is much denser than other membranes and their thickness is also higher in the upper layer. Therefore, their resistance to the permeability of water and antibiotic molecules is expected to be higher. This resistance, by adding the surfactant to the cast solution up to 8 wt%, is greatly reduced. This is mainly because of the formation of more porous structures with a thinner and low-dense top layer, through which a larger number of water and AMX molecules can be transmitted. Higher rejection of AMX can be attributed to the relatively moderate increase in the porosity of the membrane. This, in turn, reduces moderately the membrane resistance against inflow permeability. Such moderate morphological alteration can be very influential in transmitting fine particles, such as water molecules, through the membrane, rather than the larger components like AMX molecules. This causes water molecules to pass through the membrane and antibiotic molecules that are larger are left behind the membrane. In better words, the AMX molecules will be very low in the permeated outflow, and a higher rejection of AMX will occur [21]. As discussed earlier, further increase in the Merpol content up to 10 wt%, due to the creation of denser membrane structures, no longer increased the rejection rate and even caused a gradual decrease in the AMX rejection performance. Figure 5 depicts the PWF of the prepared membranes, containing different concentrations of Merpol. As the figure suggests, the amount of PWF increases to reach its maximum in the casting solution containing 8 wt% Merpol surfactant. Further addition of Merpol to the casting solution no longer improves the PWF. This is mainly due to the changes in the membrane structure and the consequent changes in its properties after the addition of Merpol.

There is a direct relationship between PWF and the number and size of pores in the membrane top layer [41]. So, even the slightest change in the surface porosity will lead to much more fluctuations in the permeate flux [42]. According to Fig. 5, the obtained results confirm the trends observed in the SEM images. As shown earlier in Fig. 2, the top layer thickness of the membranes after the addition of 2, 4, 6, and 8 wt% Merpol was decreased. This reduced the resistance of the membrane against water permeation and consequently, increased PWF. In membrane M6, containing 10 wt% Merpol, as a result of increasing the thickness of the upper layer, and thereby increasing the resistance to water penetration, the PWF is decreased.

Conclusion

Antibiotics have become emerging contaminants of aquatic ecosystems in recent years. These pollutants, even in small quantities, are dangerous due to their high persistence in aquatic ecosystems. Consequently, the removal of antibiotics before they enter the aquatic environment, as well as for water reuse is very pertinent.

This study investigated the morphology, wettability, PWF, and removal of AMX of the PES membranes after adding different concentrations of the Merpol surfactant. According to the research findings, adding Small amounts of the Merpol surfactant strongly improved the morphology and permeability of the PES membranes. Adding 2, 4, 6, and 8 wt% Merpol surfactant resulted in the formation of more porous membranes with a higher permeability. Conversely, adding higher amounts of surfactant by 10 wt % to the casting solution suppressed the microvoids and formed a denser structure with less permeability. Adding the Merpol surfactant to the casting solution also increased the wettability of the membranes. Rejection of AMX was highly related to the characteristics of the membranes, so that the initial increase in Merpol concentration up to 8 wt % resulted in the higher rejection of AMX.

Change history

14 January 2020

In the original publication of the article, the affiliation of the authors Maryam Omidvar and Zahra Hejri are incorrect; the corrected affiliation is given in this erratum article.

14 January 2020

In the original publication of the article, the affiliation of the authors Maryam Omidvar and Zahra Hejri are incorrect; the corrected affiliation is given in this erratum article.

References

Yang X et al. (2018) Biomimetic silicification on membrane surface for highly efficient treatments of both oil-in-water emulsion and protein wastewater. Appl Mater Interfaces 10(35):29982–29991

Sun H et al (2018) Segregation-induced in situ hydrophilic modification of poly(vinylidene fluoride) ultrafiltration membranes via sticky poly(ethylene glycol) blending. J Membr Sci 563:22–30

Lan L et al (2019) High removal efficiency of antibiotic resistance genes in swine wastewater via nanofiltration and reverse osmosis processes. J Environ Manag 231:439–445

Ghaemi N et al (2012) Separation of nitrophenols using cellulose acetate nanofiltration membrane: influence of surfactant additives. Sep Purif Technol 85:147–156

Zhang W et al (2003) Development and characterization of composite nanofiltration membranes and their application in concentration of antibiotics. Sep Purif Technol 30(1):27–35

Bagheri H, Afkhami A, Noroozi A (2016) Removal of pharmaceutical compounds from hospital wastewaters using nanomaterials: a review. Anal Bioanal Chem Res 3(1):1–18

Yan C et al (2008) Preparation and characterization of chloromethylated/quaternized poly(phthalazinone ether sulfone ketone) for positively charged nanofiltration membranes. J Appl Polym Sci 107(3):1809–1816

Verliefde AR et al (2009) Influence of membrane fouling by (pretreated) surface water on rejection of pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) by nanofiltration membranes. J Membr Sci 330(1):90–103

Zazouli MA, Bazrafshan E (2015) Applications, issues and futures of nanofiltration for drinking water treatment. Health Scope 4(3):e27244

Low Z-X (2018) Fouling resistant 2D boron nitride nanosheet—PES nanofiltration membranes. J Membr Sci 563:949–956

Fatemeh Seyedpour S et al (2018) Low fouling ultrathin nanocomposite membranes for efficient removal of manganese. J Membr Sci 549:205–216

Rahman NA, Maruyama T, Matsuyama H (2008) Performance of polyethersulfone/tetronic-1307 hollow fiber membrane for drinking water production. J Appl Sci Environ Sanit 3:1–7

Rahimpour A, Madaeni SS (2010) Improvement of performance and surface properties of nano-porous polyethersulfone (PES) membrane using hydrophilic monomers as additives in the casting solution. J Membr Sci 360(1):371–379

Mahdavi H, Ardeshiri F (2016) An efficient nanofiltration membrane based on blending of polyethersulfone with modified (styrene/maleic anhydride) copolymer. J Iran Chem Soc 13(5):873–880

Amirilargani M, Saljoughi E, Mohammadi T (2010) Improvement of permeation performance of polyethersulfone (PES) ultrafiltration membranes via addition of Tween-20. J Appl Polym Sci 115(1):504–513

Ghaemi N et al (2012) Fabrication of cellulose acetate/sodium dodecyl sulfate nanofiltration membrane: characterization and performance in rejection of pesticides. Desalination 290:99–106

Peng J et al (2010) Effects of coagulation bath temperature on the separation performance and antifouling property of poly(ether sulfone) ultrafiltration membranes. Ind Eng Chem Res 49(10):4858–4864

Amirilargani M, Saljoughi E, Mohammadi T (2009) Effects of Tween 80 concentration as a surfactant additive on morphology and permeability of flat sheet polyethersulfone (PES) membranes. Desalination 249(2):837–842

Rahimpour A, Madaeni S, Mansourpanah Y (2007) The effect of anionic, non-ionic and cationic surfactants on morphology and performance of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes for milk concentration. J Membr Sci 296(1):110–121

Omidvar M et al (2014) Preparation and characterization of poly(ethersulfone) nanofiltration membranes for amoxicillin removal from contaminated water. J Environ Health Sci Eng 12(1):18

Omidvar M et al (2015) Preparation of hydrophilic nanofiltration membranes for removal of pharmaceuticals from water. J Environ Health Sci Eng 13(1):42

Moarefian A, Golestani HA, Bahmanpour H (2014) Removal of amoxicillin from wastewater by self-made polyethersulfone membrane using nanofiltration. J Environ Health Sci Eng 12(1):127

Homem V, Santos L (2011) Degradation and removal methods of antibiotics from aqueous matrices—a review. J Environ Manag 92(10):2304–2347

Egea-Corbacho A, Gutiérrez Ruiz S, Quiroga Alonso JM (2019) Removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater using nanofiltration for its subsequent reuse: full-scale pilot plant. J Clean Prod 214:514–523

Wang P, Lim T-T (2012) Membrane vis-LED photoreactor for simultaneous penicillin G degradation and TiO2 separation. Water Res 46(6):1825–1837

Zazouli M et al (2010) Effect of hydrophilic and hydrophobic organic matter on amoxicillin and cephalexin residuals rejection from water by nanofiltration. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng 7(1):15

Koyuncu I et al (2008) Removal of hormones and antibiotics by nanofiltration membranes. J Membr Sci 309(1):94–101

Zazouli MA et al (2009) Influences of solution chemistry and polymeric natural organic matter on the removal of aquatic pharmaceutical residuals by nanofiltration. Water Res 43(13):3270–3280

Shahtalebi A, Sarrafzadeh M, Rahmati MM (2011) Application of nanofiltration membrane in the separation of amoxicillin from pharmaceutical wastewater. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng 8(2):109

Mousavi SM, Saljoughi E, Sheikhi-Kouhsar MR (2013) Preparation and characterization of nanoporous polysulfone membranes with high hydrophilic property using variation in CBT and addition of tetronic-1107 surfactant. J Appl Polym Sci 127(5):4177–4185

Al-Abachi MQ, Haddi H, Al-Abachi AM (2005) Spectrophotometric determination of amoxicillin by reaction with N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine and potassium hexacyanoferrate(III). Anal Chim Acta 554(1):184–189

Saljoughi E, Mousavi SM (2012) Preparation and characterization of novel polysulfone nanofiltration membranes for removal of cadmium from contaminated water. Sep Purif Technol 90:22–30

Saljoughi E, Amirilargani M, Mohammadi T (2010) Effect of PEG additive and coagulation bath temperature on the morphology, permeability and thermal/chemical stability of asymmetric CA membranes. Desalination 262(1):72–78

Saljoughi E, Amirilargani M, Mohammadi T (2009) Effect of poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) concentration and coagulation bath temperature on the morphology, permeability, and thermal stability of asymmetric cellulose acetate membranes. J Appl Polym Sci 111(5):2537–2544

Saljoughi E, Amirilargani M, Mohammadi T (2010) Asymmetric cellulose acetate dialysis membranes: synthesis, characterization, and performance. J Appl Polym Sci 116(4):2251–2259

Saljoughi E, Mohammadi T (2009) Cellulose acetate (CA)/polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) blend asymmetric membranes: preparation, morphology and performance. Desalination 249(2):850–854

Ghaemi N et al (2012) Effect of fatty acids on the structure and performance of cellulose acetate nanofiltration membranes in retention of nitroaromatic pesticides. Desalination 301:26–41

Urase T, Sato K (2007) The effect of deterioration of nanofiltration membrane on retention of pharmaceuticals. Desalination 202(1–3):385–391

Shah AD, Huang C-H, Kim J-H (2012) Mechanisms of antibiotic removal by nanofiltration membranes: model development and application. J Membr Sci 389:234–244

Nghiem LD, Schäfer AI, Elimelech M (2005) Pharmaceutical retention mechanisms by nanofiltration membranes. Environ Sci Technol 39(19):7698–7705

Mohammadi T, Saljoughi E (2009) Effect of production conditions on morphology and permeability of asymmetric cellulose acetate membranes. Desalination 243(1–3):1–7

Amirilargani M et al (2010) Effects of coagulation bath temperature and polyvinylpyrrolidone content on flat sheet asymmetric polyethersulfone membranes. Polym Eng Sci 50(5):885–893

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the officials at Islamic Azad University, Quchan Branch, for their financial support and the provision of laboratory equipment and space.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Omidvar, M., Hejri, Z. & Moarefian, A. The effect of Merpol surfactant on the morphology and performance of PES/PVP membranes: antibiotic separation. Int J Ind Chem 10, 301–309 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40090-019-0192-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40090-019-0192-5