Abstract

Purpose of the study

We assessed the prevalence of S. stercoralis in a cohort of inpatients with invasive bacterial infections of enteric origin to investigate whether the parasite may facilitate these bacterial infections even in the absence of larval hyperproliferation.

Methods

We performed a prospective cross-sectional study in a hospital in northern Italy. Subjects admitted due to invasive bacterial infection of enteric origin and potential previous exposure to S. stercoralis were systematically enrolled over a period of 10 months. S. stercoralis infection was investigated with an in-house PCR on a single stool sample and with at least one serological method (in-house IFAT and/or ELISA Bordier). Univariate, bi-variate and logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results

Strongyloidiasis was diagnosed in 14/57 patients (24.6%; 95% confidence interval 14.1–37.8%) of which 10 were Italians (10/49, 20.4%) and 4 were migrants (4/8, 50.0%). Stool PCR was performed in 43/57 patients (75.4%) and no positive results were obtained.

Strongyloidiasis was found to be significantly associated (p ≤ 0.05) with male gender, long international travels to areas at higher endemicity, deep extra-intestinal infectious localization and solid tumors. In the logistic regression model, increased risk remained for the variables deep extra-intestinal infectious localization and oncologic malignancy.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a new role of chronic strongyloidiasis in favoring invasive bacterial infections of enteric origin even in the absence of evident larval dissemination outside the intestinal lumen. Further well-designed studies should be conducted to confirm our results, and possibly establish the underlying mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Strongyloides stercoralis is a nematode (roundworm) transmitted to humans with the passage of filariform larvae (L3, up to 600 µm long) from contaminated soil through intact skin of a host.

Its life cycle is very peculiar, as a free-living sexual cycle and an asexual cycle inside the host are present [1]. The parasite cycle inside the host with the autoinfection phenomenon permits adult females (2–3 mm long) to persist potentially life-long in the hosts’ small intestinal submucosa, where they deposit eggs. From eggs, larvae hatch (L1, 180–380 µm long) that can be excreted in stool and/or enter the autoinfection cycle after conversion to L3 that penetrate the host’s large intestinal mucosa or perianal skin.

In high-income countries as Italy, migrants and international travelers from areas at higher endemicity, as well as elderly autochthonous individuals represent the three main categories at risk for the infection [2,3,4]. Autochthonous infections in young Italians without a relevant travel history are rare [5].

Complicated S. stercoralis infection involves mainly the immunocompromised population and is defined by either hyperinfection or dissemination, where a great amount of larvae invades host organ systems. The mortality of these forms can reach, respectively, 60% and 100% without treatment [6]. It is widely reported in literature how complicated strongyloidiasis may determine concomitant bacterial extra-intestinal infections of enteric origin. Enteric bacteria are not only transported directly on the surface of S. stercoralis L3 crossing larvae, but can also escape the gut lumen through parasite-determined intestinal ulcers [7, 8].

To test the hypothesis that chronic strongyloidiasis may represent a facilitating factor for bacterial extra-intestinal infections of enteric origin even in the absence of larval hyperproliferation, we conducted a prospective cross-sectional study to measure the prevalence of strongyloidiasis in a cohort of patients with severe bacterial extra-intestinal infection whose focus of origin was the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. sepsis, deep abscesses, meningitis, endocarditis, spondylodiscitis, pneumonia) and with epidemiological risk factors for this helminthiasis. The secondary purpose of the study was to identify additional epidemiological and clinical risk factors for strongyloidiasis.

Methods

Design and setting of the study

We conducted a prospective cross-sectional monocentric study at the ASST Spedali Civili of Brescia University Hospital, affiliated to the University of Brescia (Lombardy Region, North of Italy) from January to October 2021.

Study population and sample size

Eligible patients were inpatients admitted to the Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Hematology or Internal Medicine divisions due to bacterial extra-intestinal infection whose focus of origin was the gastrointestinal tract, and at least one of the following epidemiological risk criteria for strongyloidiasis: (1) Italians born in 1952 or earlier; (2) international travelers with a life-time stay of more than 14 cumulative days in countries with an estimated prevalence of strongyloidiasis ≥ 5% (estimated country-specific prevalence is reported in the supplementary material S1 of the manuscript of Buonfrate et al. [9]); (3) migrants coming from countries with an estimated prevalence of strongyloidiasis ≥ 5% [9]).

Patients were excluded if one of the following criteria was present: (1) age < 18 years; (2) denied or unable to sign the informed consent form; (3) focus of infection different from gastrointestinal tract (e.g. urinary apparatus, central venous catheter, cutaneous lesions/ulcers).

Since the background prevalence of S. stercoralis in the study population was not known, we decided to consecutively enroll patients over a pre-defined period of time.

Study procedures

Enrolled patients provided: (1) a written interviewer-administered questionnaire (see supplementary material 1) on socio-demographic characteristics, exposure and clinical factors. Medical records were consulted to retrieve clinical information; (2) a single stool sample for in-house PCR for S. stercoralis (sensitivity 86.4% (19/22) when larvae are detected with microscopy after concentration by Baermann method; sensitivity 43.8% (14/32) when larvae are not detectable with microscopy after concentration by Baermann method but with coproculture; specificity 100% [10]); (3) a blood sample to perform at least one serological test for S. stercoralis (in-house IFAT performed by laboratory of tropical microbiology of Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Negrar Hospital (Verona, Italy) (sensitivity 93.9%; specificity 92.2%) and/or ELISA Bordier kit (sensitivity 89.5%; specificity 98.3%;) [11]).

Data management

Data were entered anonymously into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, USA).

Analysis and statistical methods

Data analysis was performed using STATA software, Version SE14 (STATA Corp, USA). Variables are presented as proportions, stratified by Strongyloides status. The association between socio-demographic and clinical and behavioral parameters with Strongyloides infection was calculated using Chi2 test. A threshold of significance was defined as α = 0.05, where the null hypothesis is to be rejected when p ≤ 0.05. In tabulations with more than 20% small cell sizes (frequency < 5), Fisher’s exact test was applied. For comparison of age distribution between independent groups as non-normally distributed continuous data, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the overall proportion of Strongyloides-positive cases in the entire dataset was calculated based on the assumption of a binomial distribution. In the analytical part, odds ratios were calculated using a logistic regression model with backward selection of variables by applying the Wald test with a p value cut-off point at 0.5.

Results

A total of 57 patients were eligible and all accepted to participate in the study.

Of them, 45 (79.0%) were admitted to the Infectious Diseases division, 8 (14.0%) to the Hematology division and 4 (7.0%) to the Internal Medicine division.

The most frequent single eligibility criterion for inclusion was being an Italian citizen born in 1952 or earlier (34/57; 59.6%), followed by being a migrant (8/57; 14.0%) or having traveled to areas with estimated prevalence for strongyloidiasis ≥ 5% for at least 14 cumulative days (3/57; 5.3%). Twelve patients (21.1%) had multiple inclusion criteria (elderly Italians with relevant travel history).

Of the enrolled patients, 49/57 (86.0%) were Italian citizens; 3/57 (5.3%) were from other European countries (Albania, Russia, former Yugoslavia); 1/57 (1.8%) came from China and 4/57 (7.0%) from Africa (Morocco, Senegal, Ghana). Almost all Italian citizens were born in northern Italy, except one from central Italy and one born in Belgium. All enrolled patients resided in northern Italy at the time of study enrollment. Overall, 40/57 (70.2%) were males; the median age was 76 years (IQR 72–82).

In total, 44/57 (77.2%) enrolled patients presented an invasive infection by Enterobacteriaceae, whereas 14/57 (24.6%) by other enteric bacteria; most frequently isolated bacteria were E. coli, E. faecalis/faecium and S. gallolyticus (for details, see Fig. 1).

Most had a bloodstream infection (54/57, 94.7%), while 14/57 (24.6%) presented deep abscesses and/or other deep bacterial localizations (spondylodiscitis, endocarditis, aortitis, pneumonia), 2/57 (3.5%) had culture-positive meningitis. Only 3/57 (5.3%) had an eosinophil count ≥ 500 cells/µl at the time of admission (2 Italians and one from Morocco). One patient (1.8%) died because of hemorrhagic shock due to intestinal bleeding.

Chronic or recurrent suggestive symptoms for strongyloidiasis were referred in few cases: pruritus in 7/55 (12.7%), gastrointestinal discomfort in 3/55 (5.5%), respiratory symptoms in 3/55 (5.5%) and skin lesions in 1/55 (1.8%).

No one had clinical characteristics suggestive for disseminated strongyloidiasis.

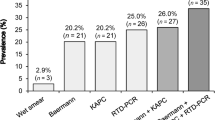

Strongyloidiasis was diagnosed in 14/57 (24.6%; 95% CI 14.1–37.8%) patients (positivity of at least one diagnostic technique), of which 10 were Italians (10/49, 20.4%) and 4 were migrants (4/8, 50.0%) (from China, Morocco, Albania and ex-Yugoslavia). Stool PCR was negative for all tested patients (43/57, 75.4%). IFAT and ELISA were both positive in 2/55 (3.6%) individuals. IFAT alone was positive in 12/55 (21.8%) subjects, while ELISA in 4/57 (7.0%). Further details are present in Table 1.

Strongyloidiasis was found to be significantly associated with male gender (p = 0.04), international travels with duration ≥ 14 continuative days to areas with estimated prevalence ≥ 5% for the parasitosis (p = 0.04), deep extra-intestinal infectious localization (p = 0.01), solid tumors (p = 0.01) and the category “other gastrointestinal disorder” (p = 0.01), that included alcoholic liver cirrhosis, gastric bypass, intestinal occlusion and pseudomelanosis coli. Presence of a hematologic malignancy was inversely correlated with S. stercoralis (p = 0.01). For details, see Tables 2, 3 and 4.

In the logistic regression model, increased risk remained with odds ratios > 1 and p ≤ 0.05 for the variables deep extra-intestinal infectious localization, oncologic malignancy and other gastrointestinal disorders (see Table 5).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical prospective cross-sectional study that investigates the association between S. stercoralis and bacterial extra-intestinal infection of enteric origin in absence of larval hyperproliferation. In literature, we only found a retrospective medical records review of patients with strongyloidiasis performed in Kentucky (USA) [12] and two case reports [13, 14] where authors speculate about this new role of strongyloidiasis.

The seroprevalence of strongyloidiasis in our cohort was higher compared with previous studies on non-hospitalized and non-septic individuals [2], both considering the criterion of one positive method (24.6%) and 2 concordant serological tests (3.6%). This was observed both in Italian and migrant subjects.

Remarkably, our cohort only included three individuals with eosinophilia and all three were negative for strongyloidiasis.

Although eosinophilia has usually been considered a key predictive sign for strongyloidiasis, our data suggest that bacterial invasive infections of enteric origin might also be considered a predictive condition. In our Italian cohort, bacterial invasive infection of enteric origin predicted a strongyloidiasis prevalence of 20.4% (one positive serological result), not different from the 28% prediction of an eosinophil count > 500 cell/µl in a study of elderly Italians tested with IFAT serology [15].

None of our participants showed a positive result by PCR on stool. This may be explained in part by the known intermittency and low parasite load in stool excreted during chronic strongyloidiasis. As a consequence, even molecular amplification techniques suffer from low sensitivity in these cases [16, 17], especially when a single stool sample per patient is analyzed. Instead, this stool result together with clinical patterns corroborate the non-hyperproliferative larval status of our patients.

In our study, we cannot determine the impact of serological cross reactions leading to potentially false-positive results. However, the serological methods we used have high sensitivity and the existing Italian seroprevalence studies share this limitation.

In the bi-variate analysis, the significant association (p ≤ 0.05) between strongyloidiasis and the single factor male gender [18] and oncologic neoplasms had already been previously reported [19].

The significant association with international travels for more than 14 continuative days to areas with an estimated strongyloidiasis prevalence ≥ 5% is of interests in terms of travel duration. Current suggestion is to screen for S. stercoralis the immunocompetent international traveler who stayed for more than 1 cumulative year in areas of higher endemicity [4]. Our result indicates that shorter staying duration in at risk areas should be considered for screening.

The significant association with deep extra-intestinal localizations of infection could involve two mechanisms, which are not mutually exclusive: the presence of deep abscesses/localizations instead of just a bloodstream infection may correspond to the peculiarity of Strongyloides larvae to migrate across organs and also deep connective tissues; in addition, as hypothesized for other helminths [20, 21], migrating larvae may induce granulomas in human organs which in turn may represent a site of bacterial attachment and replication.

We are currently unable to explain fully the statistically significant inverse correlation with hematologic malignancy. None of our patients were screened or treated before for this parasitosis. We can speculate that this population had suffer from lower sensitivity of serological diagnostic tools due to immunosuppression.

The association with the category “other gastrointestinal disorder” should be considered a spurious result considering both the exiguity of patients and heterogeneity of disorders combined under this group.

Eosinophilia and symptoms suggestive of strongyloidiasis were not predictive for this parasitosis in our cohort. Therefore, all our diagnoses, except of that made in one Moroccan immunocompromised man, would have been lost according to current recommended criteria for screening. Of note, acute bacterial infection and septic status can mask a pre-existing eosinophilia in favoring of neutrophilia, as well described in literature [22, 23].

The final logistic regression model confirmed as significant risk factors for the outcome variable Strongyloides status the independent variables deep extra-intestinal infectious localization, oncologic malignancy and the compound variable “other GI disorders”. However, the model is surely lacking power due to the limited sample size.

Based on our results, we recommend to clinicians to consider bacterial extra-intestinal infections of enteric origin, especially in case of deep localizations, as a warning sign for an underlying intestinal strongyloidiasis in patients with epidemiological risk factors for soil-transmitted helminths (see Fig. 2 for suggested decisional flow chart). In these categories, we consider elderly Italians even in the absence of relevant travel history, migrants and international travelers especially when a history of staying ≥ 14 continuative days in areas with an estimated prevalence ≥ 5% for S. stercoralis is present.

Suggested decisional flow chart for S. stercoralis screening in patients with bacterial invasive infection of enteric origin. *Elderly autochthonous Italian (even in the absence of relevant travel history), migrant or traveler with a history of staying ≥ 14 continuative days in areas with an estimated prevalence ≥ 5% for S. stercoralis

We speculate that the mechanism for the favoring role of strongyloidiasis on deep bacterial infections could be a transient crossing of low numbers of larvae through the intestinal barrier with concomitant translocation of enteric bacteria. Otherwise, the long persistence of S. stercoralis (adult female, eggs, larvae) in the human gut lumen could alter the composition of the bowel microbiome and the local and/or systemic immune response conferring a higher risk to develop enteric sepsis.

Our study has limitations, primarily the small study sample. In addition, our patients represent a population consulting a third-level medical facility; hence, external validity of our findings, e.g. towards primary care settings, may be limited as well.

Conclusions

The results of our study suggest a new role of chronic strongyloidiasis in favoring extra-intestinal bacterial infections of enteric origin even in the absence of evident larval hyperproliferation and dissemination outside the intestinal lumen. Further well-designed studies should be conducted to confirm our results, eventually establish the underlying mechanisms and the individual and social burden of this phenomenon. In the meantime, both considering the relatively low cost of diagnosis and the harmful potential of undetected strongyloidiasis, we recommend to test for this parasitosis all individuals presenting with invasive bacterial infections of enteric origin if epidemiological risk factors for the parasitosis are present.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IFAT:

-

Immunofluorescence antibody test

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

References

CDC. Strongyloidiasis [Internet]. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/strongyloidiasis/index.html. Accessed 15 Nov 2021.

Buonfrate D, Baldissera M, Abrescia F, Bassetti M, Caramaschi G, Giobbia M, et al. Epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis in northern Italy: results of a multicentre case-control study, February 2013 to July 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21:1–8.

McCarthy AE, Weld LH, Barnett ED, So H, Coyle C, Greenaway C, et al. Spectrum of illness in international migrants seen at geosentinel clinics in 1997–2009, part 2: migrants resettled internationally and evaluated for specific health concerns. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:925–33.

Requena-Méndez A, Buonfrate D, Gomez-Junyent J, Zammarchi L, Bisoffi Z, Muñoz J. Evidence-based guidelines for screening and management of strongyloidiasis in non-endemic countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:645–52.

Ottino L, Buonfrate D, Paradies P, Bisoffi Z, Antonelli A, Rossolini GM, et al. Autochthonous human and canine Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Europe: report of a human case in an Italian teen and systematic review of the literature. Pathogens. 2020;9:1–25.

Società Italiana di Medicina Tropicale e Salute Globale. Orientamenti diagnostici e terapeutici in patologia di importazione. 2017.

Boggild A, Libman M, Greenaway C, McCarthy A. CATMAT statement on disseminated strongyloidiasis: prevention, assessment and management guidelines. Canada Commun Dis Rep. 2016;42:12–9.

Leder K, Weller P. Strongyloidiasis [Internet]. UptoDate. 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/strongyloidiasis#H974799588. Accessed 20 Jan 2022.

Buonfrate D, Bisanzio D, Giorli G, Odermatt P, Fürst T, Greenaway C, et al. The global prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Pathogens. 2020;9:1–9.

Verweij JJ, Canales M, Polman K, Ziem J, Brienen EAT, Polderman AM, et al. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:342–6.

Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Sequi M, Mejia R, Cimino RO, Krolewiecki AJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of five serologic tests for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:38.

Al-Hasan MN, McCormick M, Ribes JA. Invasive enteric infections in hospitalized patients with underlying strongyloidiasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:622–7.

Te TY, Yeh CJ, Chen YA, Chen YW, Huang SF. Bilateral parotid abscesses as the initial presentation of strongyloidiasis in the immunocompetent host. Head Neck. 2012;34:1051–4.

Link K, Orenstein R. Bacterial complications of strongyloidiasis. South Med J. 1999;92:728–31.

Abrescia FF, Falda A, Caramaschi G, Scalzini A, Gobbi F, Angheben A, et al. Reemergence of Strongyloidiasis, Northern Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1531–2.

Dacal E, Saugar JM, Soler T, Azcárate JM, Jiménez MS, Merino FJ, et al. Parasitological versus molecular diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in serial stool samples: how many? J Helminthol. 2018;92:12–6.

Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Cinquini M, Cruciani M, Fittipaldo A, et al. Accuracy of molecular biology techniques for the diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:1–16.

Schär F, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, Vounatsou P, Marti H, et al. Occurrence of and risk factors for Strongyloides stercoralis infection in South-East Asia. Acta Trop [Internet]. 2016;159:227–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.03.008.

Schär F, Trostdorf U, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, Marti H, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: global distribution and risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:1–17.

Ferreira MAB, Pereira FEL, Musso C, Dettogni RV. Pyogenic Liver Abscess in children: some observations in the Espirito Santo State, Brazil. Gastroenterol Pediatr. 1997;34.

Rayes AA, Teixeira D, Serufo JC, Nobre V, Antunes CM, Lambertucci JR. Human toxocariasis and pyogenic liver abscess: a possible association. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96.

Marchese V, Crosato V, Gulletta M, Castelnuovo F, Cristini G, Matteelli A, et al. Strongyloides infection manifested during immunosuppressive therapy for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Infection [Internet]. 2021;49:539–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01522-4.

Pitman MC, Anstey NM, Davis JS. Eosinophils in severe sepsis in northern Australia: do the usual rules apply in the tropics. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:286–8.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for their collaboration all ward nurses, MDs, health assistants and administrative staff of the involved divisions. Thanks to the working group SIMET (Italian Society of Tropical Medicine and Global Health) on strongyloidiasis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GG projected the study with the assistance of GF, VM, AM, MG. GF analyzed the study data. BF helped enrolling the patients. MADF performed the in-house PCR on stool sample. FP performed serologies. FG, GP, SC helped selecting the enrolling patients based on microbiological results. CC and CP facilitated the enrollment procedures in the hematology division. MS facilitated the enrollment procedures in the general medicine division. GG and GF wrote the first draft of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and approved by Ethics Committee of Spedali Civili Hospital of Brescia on 12 January 2021 (opinion number 4561). A written informed consent was acquired from each enrolled patient.

Consent for publication

Each enrolled patient signed the informed consent for publication.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

15010_2023_2072_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary material 1: Written interviewer-administered questionnaire on socio-demographic characteristics, exposure and clinical factors (English version), pdf format. (DOCX 19 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gardini, G., Froeschl, G., Gurrieri, F. et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an underlying cause of invasive bacterial infections of enteric origin. Results from a prospective cross-sectional study of a northern Italian tertiary hospital. Infection 51, 1541–1548 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-023-02072-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-023-02072-1