Abstract

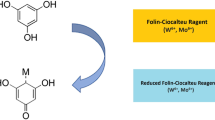

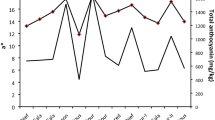

Chelidonium majus, from Papaveraceae family, is a rich source of different antioxidants with a range of medicinal activities including antispasmodic and diuretic properties. In this study, antioxidant potential of extracts from leaves during different phenological stages was measured by ferric-reducing power (FRAP) and 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity. Factors affecting antioxidant activity, i.e., total phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanin and carotenoids, were then investigated. Soluble sugar and total protein contents of samples were also determined. According to the results, maximum DPPH radical scavenging activity was 408/88 ± 24/83 g/g DW at growing stage, and the FRAP value reached maximum during fruiting stage (1.75 ± 0.04 mg/g FW). The leaves of flowering stage contained the most content of total phenol (17.8 ± 1.59 mg/g DW), flavonoid (69.7 ± 0.86 mg/g DW), anthocyanin (0.233 ± mg/g DW) and soluble sugar (0.338 ± 0.009 mg/g DW). However, the highest value for carotenoid (2.083 mg/g DW) and protein (0.27 ± 0.034 mg/g DW) was found at the vegetative stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

12 September 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Paul A, Das J, Das S, Samadder A, Khuda-Bukhsh AR (2013) Poly (lactide-co-glycolide) nano-encapsulation of chelidonine, an active bioingredient of greater celandine (Chelidonium majus), enhances its ameliorative potential against cadmium induced oxidative stress and hepatic injury in mice. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 36(3):937–947

Takable W, Niki E, Uchida K, Yamada S, Satoh K, Noguchi N (2001) Oxidative stress promotes the development of transformation: involvement of a potent mutagenic lipid peroxidation product, acrolein. Carcinogenesis 22:935–941

Schulz JB, Seyfried J, Dichgans J (2000) Glutathione, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Eur J Biochem 267:4904–4911

Poli G, Parola M (1997) Oxidative damage and fibrogenesis. Free Rad Biol Med 22:287–292

Duthie G, Crosier A (2000) Plant-derived phenolic antioxidants. Curr Opin Lipidol 11(1):447–451

Tsuchiya H, Ueno T, Tanaka T, Matsuura N, Mizogami M (2010) Comparative study on determination of antioxidant and membrane activities of propofol and its related compounds. Eur J Pharm Sci 39(1–3):97–102

Prior RL, Cao G, Prior RL, Cao G (2000) Analysis of botanicals and dietary supplements for antioxidant capacity: a review. J AOAC Int 83(4):950–956

Rice-Evans CA, Sampson J, Bramley PM, Holloway DE (1997) Why do we expect carotenoids to be antioxidants in vivo? Free Radic Res 26(4):381–398

Nadova S, Miadokova E, Alfoldiova L, Kopaskova M, Hasplova K, Hudecova A, Vaculcikova D, Gregan F, Cipak L (2008) Potential antioxidant activity cytotoxic and apoptosis-inducing effects of Chelidonium majus L. extract on leukemia cells. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 29(5):649–652

Arora S, Singh S, Piazza GA, Contreras CM, Panyam J, Singh AP (2012) Honokiol: a novel natural agent for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Mol Med 12(10):1244–1252

Marin GH, Mansilla E (2010) Apoptosis induced by Magnolia Grandiflora extract in chlorambucil-resistant B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. J Cancer Res Ther 6(4):463–465

Ikeuchi M, Tatematsu K, Yamaguchi T, Okada K, Tsukaya H (2013) Precocious progression of tissue maturation of leaflets in Chelidonium majus subsp asiaticum (Papaveraceae). Am J Bot 100(6):1116–1126

Park JE, Cuong TD, Hung TM, Lee I, Na M, Kim JC, Ryoo S, Lee JH, Choi JS, Woo MH, Min BS (2011) Alkaloids from Chelidonium majus and their inhibitory effects on LPS-induced NO production in RAW264.7 cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21(23):6960–6963

Jakovljevic ZD, Stankovic SM, Topuzovic DM (2013) Seasonal variability of chelidonium majus L. secondary metabolites content and antioxidant activity. EXCLIN J 12:260–268

Colombo ML, Bosisio E (1996) Pharmacological activities of Chelidonium majus L. (Papaveraceae). Pharmacol Res 33(2):127–134

Habermehl D, Kammerer B, Handrick R, Eldh T, Gruber C, Cordes N, Daniel P, Plasswilm L, Bamberg M, Belka C, Jendrossek V (2006) Proapoptotic activity of Ukrain is based on Chelidonium majus L. alkaloids and mediated via a mitochondrial death pathway. BMC Cancer 6(14):1–22

Nowicky JW, Staniszewski A, Zbroja-Sontag W, Slesak B, Nowicky W, Hiesmayr W (1991) Evaluation of thiophosphoric acid alkaloid derivatives from Chelidonium majus L. (“Ukrain”) as an immunostimulant in patients with various carcinomas. Drugs Exp Clin Res 17(2):139–143

Papuc C, Crivineanu M, Nicorescu V, Predescu C, Rusu E (2012) Scavenging activity of reactive oxygen species by polyphenols extracted from different vegetal parts of celandine (Chelidonium majus). Chemiluminescence Screening. Rev Chim 63(2):193–197

Gañán NA, Dias AM, Bombaldi F, Zygadlo JA, Brignole EA, de Sousa HC, Braga ME (2016) Alkaloids from Chelidonium majus L.: fractionated supercritical CO2 extraction with co-solvents. Sep Purif Technol 165:199–207

Benzie IFF, Strain JJ (1996) The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem 239:70–76

Miliauskas G, van Beek TA, de Waard P, Venskutonis RP, Sudhölter EJ (2005) Identification of radical scavenging compounds in Rhaponticum carthamoides by means of LC-DAD-SPE-NMR. J Nat Prod 68(2):168–172

Wu X, Beecher GR, Holden JM, Haytowitz DB, Gebhardt SE, Prior RL (2006) Concentrations of anthocyanins in common foods in the United States and estimation of normal consumption. J Agric Food Chem 54(11):4069–4075

Luo X, Huang Q (2011) Relationships between leaf and stem soluble sugar content and tuberous root starch accumulation in cassava. J Agric Sci 3(2):64–72

Lamien-Meda A, Lamien CE, Compaoré MM, Meda RN, Kiendrebeogo M, Zeba B, Millogo JF, Nacoulma OG (2008) Polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of fourteen wild edible fruits from Burkina Faso. Molecules 13(3):581–594

Hadaruga DI, Hadaruga NG (2009) Antioxidant activity of Chelidonium majus L. extracts from the Banat county. J Agroaliment Process Technol 15(3):396–402

Maji AK, Banerji P (2015) Chelidonium majus L. (Greater celandine)—a review on its phytochemical and therapeutic perspectives. Int J Herb Med 3(1):10–27

Vahlensieck U, Hahn R, Winterhoff H, Gumbinger HG, Nahrstedt A, Kemper FH (1995) The effect of Chelidonium majus herb extract on choleresis in the isolated perfused rat liver. Planta Med 61(3):267–271

Pandey KB, Rizvi SI (2009) Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2(5):270–278

Lahouel M, Boulkour S, Segueni N, Fillastre JP (2004) The flavonoids effect against vinblastine, cyclophosphamide and paracetamol toxicity by inhibition of lipid-peroxydation and increasing liver glutathione concentration. Pathol Biol (Paris) 52(6):314–322

Lotito SB, Frei B (2006) Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon? Free Radic Biol Med 41(12):1727–1746

Woo HD, Kim J (2013) Dietary flavonoid intake and smoking-related cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 8(9):e75604

Ravishankar D, Rajora AK, Greco F, Osborn HM (2013) Flavonoids as prospective compounds for anti-cancer therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45(12):2821–2831

Vieira AR, Abar L, Vingeliene S, Chan DSM, Aune A, Navarro-Rosenblatt D, Stevens C, Greenwood D, Norat T (2016) Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 27(1):81–96

Leoncini E, Nedovic D, Panic N, Pastorino R, Edefonti V, Boccia S (2015) Carotenoid intake from natural sources and head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24(7):1003–1011

Song JY, Yang HO, Pyo SN, Jung IS, Yi SY, Yun YS (2002) Immunomodulatory activity of protein-bound polysaccharide extracted from Chelidonium majus. Arch Pharmacal Res 25(2):158–164

Halliwell B (2007) Oxidative stress and cancer: Have we moved forward? Biochem J 401(1):1–11

Battle TE, Arbiser J, Frank DA (2005) The natural product honokiol induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) cells. Blood 106(2):690–697

Aljuraisy YH, Mahdi NK, Al-Darraji MNJ (2012) Cytotoxic effect of Chelidonium majus on cancer cell. Al-Anbar J Vet Sci 5(1):85–90

Lee DH, Szczepanski MJ, Lee YJ (2009) Magnolol induces apoptosis via inhibiting the EGFR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in human prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 106:1113–1122

El-Readi MZ, Eid S, Ashour ML, Tahrani A, Wink M (2013) Modulation of multidrug resistance in cancer cells by chelidonine and Chelidonium majus alkaloids. Phytomedicine 20(3–4):282–294

Acknowledgment

The study was partly supported by Zanjan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s13765-017-0318-4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khodabande, Z., Jafarian, V. & Sariri, R. Antioxidant activity of Chelidonium majus extract at phenological stages. Appl Biol Chem 60, 497–503 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13765-017-0304-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13765-017-0304-x