Abstract

Global and national policy frameworks emphasize the importance of people’s participation and volunteers’ role in disaster risk reduction. While research has extensively focused on volunteers in disaster response and recovery, less attention has been paid on how organizations involved in disaster risk management can support volunteers in leading and coordinating community-based disaster risk reduction. In 2019, the New Zealand Red Cross piloted the Good and Ready initiative in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, with the objective to empower local people in resilience building with a focus on volunteers and community participation. This research examined the positive and negative outcomes of Good and Ready and investigated volunteers’ experiences in the disaster resilience initiative. It involved the codesign of a questionnaire-based survey using participatory methods with Good and Ready volunteers, the dissemination of the survey to gather volunteers’ viewpoints, and a focus group discussion with participatory activities with Red Cross volunteers. The findings highlight that a key challenge lies in finding a balance between a program that provides flexibility to address contextual issues and fosters communities’ ownership, versus a prescriptive and standardized approach that leaves little room for creativity and self-initiative. It pinpoints that supporting volunteers with technical training is critical but that soft skills training such as coordinating, communicating, or facilitating activities at the local level are needed. It concludes that the sustainability of Good and Ready requires understanding and meeting volunteers’ motivations and expectations and that enhancing partnerships with local emergency management agencies would strengthen the program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Policy frameworks at the global and national levels stress the importance of people’s participation for disaster risk reduction (DRR). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2023 (UNDRR 2015) emphasizes that DRR requires local communities’ empowerment and inclusive, accessible, and non-discriminatory participation. It highlights that “special attention should be paid to the improvement of organized voluntary work of citizens” (UNDRR 2015, p. 13). In Aotearoa New Zealand, the national disaster resilience strategy has the main goal “to strengthen the resilience of the nation […] by enabling, empowering and supporting individuals, organizations and communities to act for themselves and others, for the safety and wellbeing of all” (MCDEM 2019, p. 3).

Participation and empowerment of people are only possible if DRR actions are community-based (Delica-Willison and Gaillard 2012). Community-based disaster risk reduction (CBDRR) emerged as a bottom-up alternative paradigm in the 1980s and 1990s in developing countries, largely in response to complex political and socioeconomic situations. In the Philippines CBDRR approaches developed because of martial laws in the 1970s and 80s. A national network of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) named the Citizens Disaster Response Network was established in the 1980s. It fostered communities’ participation and focused on the organizational capacity of vulnerable sectors via the establishment of grassroots disaster response organizations (Heijmans and Victoria 2001). In Latin America, the Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América Latina (La Red) was created in 1992. La Red drew upon disaster experiences at the local level to promote change in the national and international policies focused on preparedness, response, and research (Heijmans 2009). In Africa, the umbrella organization called Partners Enhancing Resilience to People Exposed to Risks (Periperi) was created in 2006 with a focus on risk reduction actions in the continent related to vulnerability, livelihood, and developmental issues.

Central to CBDRR is the recognition that local communities have capacities in dealing with hazards and disasters. Capacities refer to the knowledge, skills, and resources that people claim, access, and mobilize to deal with hazards and disasters (Gaillard et al. 2019). These are both individual and collective. The concept of capacities overlaps with the older concept of disaster subculture developed in the 1960s and 1970s by sociologists and psychologists documenting communities’ actions in the face of recurring hazards and disasters. Subculture has been defined as “those adjustments, actual and potential, social, psychological, and physical, which are used by residents of such areas to cope with disasters which have struck, or which tradition indicates may strike in the future” (Moore 1964, p.195). Subculture encompasses the norms, technologies, values, knowledge, and resources mobilized to prevent, prepare for, and response to hazards and disasters (Wenger and Weller 1973). Both subculture and capacities have been critical to the development of CBDRR.

Key to CBDRR lies also in recognizing disasters as local issues and thus, local communities have legitimacy to act upon matters that affect their lives. This entails communities’ participation to identify DRR solutions (Maskrey 2011). Participation is a voluntary process by which people, including those powerless and marginalized, can shape or control the decisions that affect them. Participation emphasizes the need to incorporate people’s views, expertise, actions, and priorities in DRR. Genuine participation shall result in socio-culturally appropriate actions that address local concerns. Outside stakeholders like government agencies, NGOs, and scientists should facilitate the participatory process and provide resources to support people’s decisions and actions (Chambers 1994). Community-based DRR and people’s participation has involved the development of toolkits and methodological frameworks such as Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) and Participatory Action Research (PAR). Both those tools and methodological frameworks were critical and emblematic of the expansion of community-based approaches for DRR.

While community-based approaches and the alternative participatory paradigm gained traction in different continents, they also received virulent critiques. People on the ground have been acting upon disaster-related issues long before formal disaster-related mechanisms existed and have continued to do so with, despite, or in the absence of, formal CBDRR (Bankoff 2017). Some argued that participation is tyrannical (Cooke and Kothari 2001), emphasizing CBDRR is an end, rather than a means to an end, that agencies use to obtain funding. Others critiqued the concept of “community” pinpointing that communities are not homogenous, are composed of members with competing interests and different levels of power and access to resources (that is, gender, ethnicity, caste, class, age, and so on). Therefore, such intra-community disparities are difficult for outside stakeholders to grasp and CBDRR involving participatory methods prove limited to overcome these issues (Guijt and Shah 1998; Titz et al. 2018). These critiques nonetheless did not impede the development of community-based approach to DRR and disaster management and often encouraged researchers and practitioners to reflect upon their practices to improve (Le Dé et al. 2014; Bubb and Le Dé 2022).

In high-income countries the concept of CBDRR has been less popular than in lower-income nations and has manifested differently. Participation and community-based initiatives have often taken the form of citizens volunteering in disaster response and recovery rather than preparedness and tackling the root causes of disaster risk (Simpson 2001; Barbour and Manly 2016; Grant and Langer 2019). People have always converged in the disaster affected areas to help those impacted in clearing of debris, search and rescue efforts, and the relief and early recovery actions (Drabek and McEntire 2003; Whittaker et al. 2015). The emergent behaviors of volunteers generally occur in response to emergencies when impacted people’s needs are not addressed or are perceived as unmet by the formal organizations responding (Haynes et al. 2020). Spontaneous volunteering, convergence on disaster site to volunteer, and the related phenomena of emergent organization and behavior during and after crisis, have thus called the attention from disaster scholars and practitioners for decades. Practitioners and researchers have focused on issues of coordination of volunteer, communication, training, mental health support, and health and safety when citizens participate in the response and recovery actions (Quarantelli 1984; Whittaker et al. 2015; Twigg and Mosel 2017) among other aspects. However, formal agencies encouraging volunteering have procedures in place, are bound by legislative requirements, and generally use command-and-control approaches, making it difficult to create opportunities for people’s participation. When the 2011 Christchurch earthquake occurred, Sam Johnson, who then became the lead of the Student Volunteer Army that played a key role in the disaster response, was initially rejected by emergency management agencies for not having formal training delivered by those organizations. This example illustrates well the tensions between “formal” agencies and “unformal” community-based initiatives.

Many scholars argue that, in high-income countries, disaster-related agencies tend to create opportunities for community participation within their organizations, and by this means keep control over who participates and how (Bajek et al. 2008; Haynes et al. 2020; Nahkur et al. 2022). In Japan, Jishu-Bosai-Soshiki have been developed for disaster preparedness and rescue activities at the community level, but these largely take the form of “compulsory participation” driven by local governments (Bajek et al. 2008, p. 284). In Australia, there has been different community-based initiatives focused on preparedness to bushfire such as through the establishment of Community Fire Unit trained by certified agencies where working “outside the rules” can be challenging (Haynes et al. 2020). In the United States, Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT) represent one of the most popular forms of citizen-led initiatives for disaster preparedness across 50 states (Carr and Jensen 2015). The CERT developed in the mid-1980s from the desire of local citizens willing to respond to disasters in their own neighborhoods without relying on the local government for assistance. The CERTs are now supported by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and certified professionals who “train people to be better prepared to respond to emergency situations in their communities” (Carr and Jensen 2015, p. 1552). The CERTs model has been applied to schools through the SERT (School Emergency Response Training) to “ensure the intersection between disaster-related education, school safety, and community disaster response while training the next generation to be responsible citizens who care about and contribute to their community (Rich and Kelman 2013, p. 60).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, emergency and disaster management agencies rely on citizen volunteers to participate in different activities. These include Civil Defense and Emergency Management, Fire and Emergency New Zealand, the New Zealand Red Cross (NZRC), Surf Life Saving New Zealand, and Land Search and Rescue New Zealand, to name a few. Those volunteers are usually well-trained, must operate within certain rules, adhere to strict code of conduct, and are considered members of the organization. Furthermore, volunteers generally do not engage with local people in planning and decision making for DRR but deliver response efforts to those communities during emergencies (Grant and Langer 2019). Overall, the New Zealand organizations’ programs empowering local volunteers in working with their communities on disaster prevention and planning are limited (Grant and Langer 2021). This is even though research conducted in high income countries where this approach has been implemented often proves successful in reducing risk and enhancing social cohesion and resilience (McGee 2011; Lalone 2012; MacDougall et al. 2014). Research evaluating such initiatives is scarce but critical to understanding how relevant agencies can successfully support people’s participation and CBDRR (Carr and Jensen 2015; Whittaker et al. 2015; Barbour and Manly 2016; Haynes et al. 2020).

In 2019, the NZRC initiated the Good and Ready (G&R) program aimed at empowering local communities to better prepare for, cope with, and recover from hazards and disasters with a focus on volunteers and community participation. The initiative’s objectives were to enhance the NZRC links with local communities to support communities’ preparedness and resilience while reimagining volunteering to reflect Aotearoa New Zealand’s diverse and changing society and empower local communities for DRR. In practice, the approach involved training and supporting local people who volunteer to lead and coordinate actions in their locality towards fostering community disaster preparedness. After 2 years of piloting the initiative, this research was developed with two main objectives: (1) To identify the strengths and weaknesses of the G&R project while also examining the challenges and opportunities to improve it; and (2) to explore volunteers’ motivations, views, experiences and how to improve volunteering in disaster resilience programs.

2 Good and Ready Initiative: An Overview

Good and Ready started in July 2019 in collaboration with the Emergency Management groups from the Auckland Council. The objective was to promote inclusiveness and empower local communities for DRR actions. There were four key areas: (1) volunteers’ engagement; (2) community engagement; (3) project management; and (4) emergency activation support. It was created to be a community-led program. Good and Ready was introduced through emergency preparedness workshops and training, focusing on building resilience in “at-risk” communities. The premise was that a connected community is a prepared community, using a “connect, care and prepare” approach. The main measurable objectives were to (1) create a Grab Bag (that is, emergency preparedness kit); (2) make an emergency household plan with friends and whanau (family); and (3) connect and share information with a G&R Buddy. The NZRC accessed existing community relationships with stakeholders and Auckland Red Cross teams such as the Migrant program, Disaster Welfare Response Team (DWST), and Community Activators who already worked with local groups. The focus was to develop local emergency preparedness “champions,” who were inspired to take a lead role in starting conversations and foster local communities’ participation to help increase awareness about disasters and strengthen disaster preparedness. The volunteers would use the NZRC support and resources into their own communities, to ultimately be “good and ready” should a hazard or disaster happen. The completion of the pilot project sparked the interest from other areas of Aotearoa New Zealand for replication. Nonetheless, there was a need to understand how successful this model is, and what are the opportunities and challenges for replication in other cities.

3 Research Design

The research used both qualitative and quantitative research methods with a three-step data collection process involving (1) the codesign of a questionnaire-based survey through workshops using participatory methods with G&R volunteers; (2) the dissemination of the questionnaire-based survey to gather volunteers’ knowledge and viewpoints about the G&R initiative; and (3) the facilitation of a focus group discussion (FGD) using participatory methods for volunteers to self-reflect on the questionnaire-based survey findings and explore ways to improve their engagement in disaster-related initiatives. Ethics approval was granted with application number 21/77 at Auckland University of Technology.

Step 1 used participatory methods for Red Cross volunteers to design the questionnaire-based survey. The rationale was for Red Cross volunteers to take ownership of the process while recognizing that they are the best placed to create a questionnaire on volunteering in G&R. Two online workshops were conducted using Mural boardsFootnote 1in July 2021. In total, 15 joined the first FGD and 12 participants participated in the second FGD. Each FGD lasted about 2 h. The participatory activities used to develop the questionnaire are detailed in Table 1.

The approach gave rise to insightful discussions and was an opportunity for volunteers to reflect on gaps, challenges, and opportunities to improve volunteering and G&R. Figure 1 provides an example of the Mural board with the different questions to be asked and themes discussed. The approach aligns with the CBDRR and participation paradigm.

Four themes structured the questionnaire: (1) background and demographics of volunteers; (2) success and performance of the G&R initiative; (3) volunteers’ engagement in G&R; and (4) how to improve the G&R project, with a total of 26 questions. This information was transcribed into a Word document circulated to the participants for additional comments. The research team then transferred the questionnaire to the Qualtrics platformFootnote 2 to administer it online. The survey was distributed via email to 145 volunteers who lead/coordinate G&R initiative in their neighborhood, with 77 opening it and 28 filling the questionnaire. A total of 21 questionnaires were included in the final data analysis. Seven responses were excluded due to either ineligibility to participate in the survey or discontinuation after the eligibility screening.

The last step of this study involved the volunteers who analyzed the survey findings. A FGD using participatory methods was conducted with NZRC volunteers in February 2023. It was composed of 12 G&R and DWST volunteers. The goals were to (1) gather insights about volunteering at the Red Cross in disaster-related programs; and (2) identify ways to improve both volunteering in these initiatives and the success of those programs. The FGD lasted about 3.30 h and was self-reflective with participants sharing their experiences, expectations, difficulties, successes, and ideas about volunteering. The FGD first debriefed the survey findings and used the Participatory Action Research methods to reflect upon the volunteers’ experiences and develop an action plan (that is, what, who, when) to improve. It also involved the assessment of G&R and an emergency response program named DWST by using a Strength, Needs, Opportunities, Challenges (SNOC) analysis. Lastly, the research team asked the participants about their role as volunteers, what they would ideally see being their volunteering role, and what is needed to fulfil their current and ideal volunteer role.

4 Findings

This section presents the key findings from the study. It first details the results from the questionnaire-based survey to then examine the information produced by volunteers at the FGD using participatory tools.

4.1 Results from the Online Survey

The questionnaire comprised a total of 26 questions based on the participatory workshop with volunteers. It was organized into five sections: (1) Participant information sheet; (2) Eligibility screening; (3) Sociodemographic information; (4) Participants’ experiences in G&R program; and (5) G&R program performance and suggestions for further improvements. A total of 28 volunteers responded, and 21 were included in the final analysis. Among the 21 analyzed respondents, 15 completed the questionnaire fully, whereas six did not answer all the questions. The collected responses were exported and analyzed using Microsoft Excel due to the manageable number of responses. Built-in tools of Microsoft Excel, such as pivot tables and visualization functions, were utilized for data analysis.

4.1.1 Background and Demographics of Volunteers

The G&R volunteers responded to the online survey in September 2022. A total of 28 participants answered the questionnaire and 21 were analyzed, including 12 females and 9 males. Most participants were 45–64 years (n = 10), followed by the 25–44 years age group (n = 8). Volunteers with European ethnicities (n = 10) were the main survey respondents while there were six Asian volunteers and four were from Africa and Pacific Island Countries. One Māori volunteer responded to this survey. This is overall representative of Aucklanders’ ethnicity. More than half of the participants (n = 14) were affiliated with community groups, such as religious and spiritual societies (n = 6), social groups (n = 4), and sports (n = 2) and non-political service organizations (n = 2).

Most respondents (n = 10) have been volunteering for the NZRC for the last 1–3 years. Some participants (n = 9) have been deployed with the DWST (n = 3), Meals on Wheels (n = 3), or other programs (n = 3) of the NZRC such as Auckland Area Council. Out of the 15 respondents to NZRC training, only nine of them completed the G&R training, either a half-day G&R Induction Training Course or an hour G&R Emergency Preparedness Workshop, or both. Seven participants attended the Red Cross Comprehensive First Aid (CFA) training. The rest of them (n = 4) completed either the Red Cross Psychological First Aid Training or the Red Cross Disaster Activation Training. In brief, 15 out of the 21 respondents accomplished at least one NZRC training while five of them have joined two or three types of training.

Six participants thought that their communities are geographically, environmentally, and climatically at risk. Seven participants chose the “don’t know” category with regard to all three disaster risks. In terms of individual risks, nine participants believed that they were geographically at risk while eight of them chose climate risk. Ten participants considered their communities were at risk of environmental hazards. By the time they answered this survey (September 2022), 13 participants indicated that they had never or rarely experienced a disaster before and only one responded with having often experienced disasters. This is likely to have changed since the Auckland region was affected by severe floods in January 2023 and ex-tropical cyclone Gabrielle in February 2023.

4.1.2 Success and Performance of the Good and Ready Initiative

The survey included questions regarding the success and performance of the G&R initiative and its training (see Fig. 2). Out of 15 respondents,12 volunteers (80%) expressed comfort in sharing the messages they received from the G&R training. They also indicated that they felt prepared should an emergency happen. The majority (60%) also acknowledged the sustainability of the G&R program.

Volunteers additionally appreciated other aspects of the G&R initiative that are “working well.” They expressed that the concept of the G&R program and its communication and training have demonstrated remarkable efficacy. Some example comments are:

“It encouraged us to try different ways of engaging with the community.”

“Resources and training are good and fit for purpose. [name of Red Cross coordinator] is great to deal with.”

“People working together for the common good.”

“It’s being improved all the time.”

“The G&R team is committed to making the program a success.”

However, only 8 out of 15 respondents (53%) reported receiving adequate community engagement materials from the Red Cross and actively utilizing the skills acquired through the G&R training. Additionally, 47% perceived that the G&R initiative improves their community engagement, while 60% of respondents expressed neutral or disagreed with the notion that this program has proven beneficial to the community. The participants proposed ideas to measure the success of the G&R initiative. Some individuals suggested tracking the number of volunteers involved or the frequency of events as indicators of success. The most recuring replies were on asking directly the community members participating in CBDRR and evaluating community preparedness, with some examples below:

“[we need to] Follow up to assess the degree of community uptake and behavior change.”

“Are the communities we work with more prepared in the event of an emergency?”

“Endorsements of the benefits from communities.”

“The feedback from community or neighborhood attendees on G&R outreach can be a good yardstick to measure the success of the program.”

“By the number of events Good & Ready either leads or support. It has been challenging over the past few years, to try and build the program through all of the COVID challenges.”

4.1.3 Volunteers’ Engagement with the Good and Ready Initiative

Among the 21 participants, five volunteers heard about the G&R program through an online search and the area councils, while eight of them joined the program after finding it on social media (n = 4) and through other Red Cross volunteers and employees (n = 4). Short answers also gathered the reasons for joining the G&R program. Most answers were to help the community in a disaster. Some have had previous experiences in disasters, hoping to help the community in the face of hazards or disasters. The example responses to this question are:

“I have experience with tsunami in South Asia. So, I can help.”

“I’m used to work in the field of disasters, so I was naturally looking to volunteer for something in a similar field.”

“To support community development and emergency preparedness in my suburb/city. To learn practical skills to support my community’s resilience in response to climate change. To find out more about Red Cross while considering whether to join the DWST.”

“I joined the program because the impact of a disaster could be reduced and managed if people are told how to mitigate hazards, prepare and respond to a potential disaster event.”

“I had previous experience in emergency response and decided to join Red Cross to see if it was possible to be deployed to support emergencies.”

Volunteers thought that the G&R training was easy to join (67%) and relevant (87%) (Fig. 3). The communication was good (80%), and the training received was inclusive of different communities (73%). Overall, they would recommend the G&R program to others (80%). On the other hand, the survey also revealed that the G&R training did not meet some volunteers’ expectations (43%). Seven out of 15 respondents (47%) were generally not clear about their role as G&R volunteers and volunteering was generally not satisfactory or rewarding for 40% of the respondents. As a result, five of the 15 respondents to this question (33%) did not feel valued as volunteers.

In total, 12 out of 15 volunteer respondents (80%) are comfortable with sharing messages from the G&R training. Family/whānau is the primary individuals with whom the volunteers would share the messages (n = 12), followed by the community members (n = 8), the workplace (n = 7), and school (n = 7). We also asked about their learning experiences as G&R volunteers in this survey. The participants provided general answers about being a Red Cross volunteer. Some specified their learning context as:

“I have learned about the work of the Red Cross and become more aware of hazards in my community.”

“Psychological first aid course has been helpful in many situations encountered in daily life. Basic emergency preparation. Group skills.”

“How to prepare for and respond in the event of an emergency.”

“Regular meetings with the community can improve awareness of people at risk of local hazards and their commitment to being prepared for eventualities.”

“How to serve the community and how to be prepared if any emergency happened.”

“It’s all about community engagement.”

“Still learning how to apply it within different community groups.”

4.1.4 On Ways to Improve Good and Ready

The respondents liked being volunteers at the Red Cross and part of the G&R team itself. They enjoyed helping communities while sharing ideas about disasters and hazards. They also believed that communication and teamwork work well with the G&R program. However, several ideas are proposed to further improve the program. The majority (n = 5) suggested recruiting more volunteers and having more events and activities with better coordination. They also remarked that:

“I would like our team to conduct targeted outreach to share information and build relationships with stakeholders. Also, we can organize pre-scheduled neighborhood/community meetings to provide information on the G&R program.”

“I came into this field with very little hands-on experience. I support the overall goals but have felt at a loss about what I should be doing. Personally, I would prefer more certainty about meetings and activities, for example, a scheduled meeting once a month then activities timed around Neighbors Day, the Red Cross appeal and perhaps one other date. Perhaps volunteers could be grouped into local teams that then work together on events.”

“Link it better with other DRM elements, including basic first aid and PFA [psychological first aid] and clarity about community resilience.”

“I struggle to be proactive in my community, so help with that.”

“Better coordination and a more practical program.”

Despite having good communication within the team, the participants also believed that their engagement with the communities needs to be improved. The participants indicated several challenges and barriers faced in implementing the program in their local community, including:

“Lack of training therefore I don’t feel comfortable talking with my community.”

“Availability, interest, engagement [of local people] with the topic, appreciated support on hospitals and food delivery.”

“It has not been easy to explain and therefore to promote. Need to make it more relevant to specific risks.”

“The program has low visibility, most people I know have never heard of it. I feel a lot could be done through targeted public relations and social media to get the messages out.”

“In my discussion with some people, there is that misconception that disaster only happens in Christchurch. So, engaging these people that have not experienced a disaster on the importance of being ready before a disaster occurs was a challenging task.”

“I don’t have enough connection with my community, and I am quite shy, those are my challenges personally.”

“People not interested or too busy.”

The researchers ensured that the Qualtrics survey encompassed all questions from the participatory workshops. Yet it also added an open-ended question to uncover the opinions of G&R volunteers regarding their initiative. Some examples of their comments include:

“I don’t feel any engagement with G&R, I don’t feel comfortable in my role as a volunteer. It’s not what I thought it would be like.”

“It was a pleasure to join this group although my expectations were more related to an emergency response regarding environmental topics.”

“Good to see it can be developed further and become more useful as well as a channel to promote Red Cross and community resilience.”

“I think it would be easier to recruit new volunteers if they were aware of the requirements and commitment from the outset—meeting times, sort of activities, regular events. Great to have an opportunity to contribute ideas and initiate activities as well, but some structured activities to begin with.”

“More activities to engage the volunteers.”

“Because my English is not good, I need a friend who can speak Chinese to volunteer together, thank you.”

4.2 Findings Based on the Focus Group Discussion Using Participatory Methods

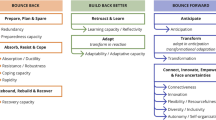

The in-person FGD investigated more in-depth the aspects captured in the questionnaire-based survey. The participants were asked about the strengths and needs associated with the programs they volunteered in. The activity proved to be a reflection of both the actual strengths and needs of the programs they were involved in, but also what they thought was critical to any disaster resilience program having volunteers.

The participants thought their role was to help, educate, support, and prepare communities to face emergencies and disasters. The majority of the participants highlighted the importance of training provided by an experienced team. They stressed the importance of in-person training/gathering, which enables volunteers to meet and work together. It is important to note that the FGD took place after a 2-year period of COVID-19 with multiple policies restricting in-person gathering. The ability to share knowledge and experience was seen as a critical aspect of volunteering in the disaster programs, including with young and new volunteers.

The participants emphasized the networking among Red Cross team members and local communities, the ability to become an enabler and a leader. The mental health support available for volunteers was seen as critical since they often experience fatigue, and difficult tasks expose them to community struggle and trauma. People reflected upon several aspects that keep volunteers actively involved. This included the sense of belonging to an organization like the NZRC, the reward associated with helping others, and the trust relationship between team members/volunteers as well as connections with local communities.

In contrast, people highlighted the need for more volunteers and new/better communication methods were identified as a significant need. This was particularly important for volunteers to be able to help each other and be more connected. They proposed creating a buddy system to allow volunteers from different social segments to feel welcomed, valued, and appreciated regardless of their social, cultural, and economic profile. More regular meetings and better rostering for volunteering was seen as critical. People explained being over-worked, busy, tired, and that stronger communication and coordination would help them conduct their diverse roles. Many of the suggestions aligned with the responses from the questionnaire-based survey.

More training to enhance confidence was seen as critical. Those involved in G&R (focusing on preparedness) thought they often lack direction as to what to do and that training would help them address this issue. This was not the case for those involved in disaster response (DWST). The participants also mentioned that there is a gap between G&R and DWST (and more generally between preparedness and response work). More training was mentioned to bridge the gap and strengthen collaboration. Enjoyment and fun activities were seen as essential to keep the volunteers engaged: these were not missing from the existing programs but rather seen as critical need for volunteers to remain in programs and for programs to be successful. In line with this, the participants acknowledged the satisfaction of helping others and overall, feeling valued as a critical dimension of volunteering. They mentioned that ID cards or some way of identifying those volunteering was needed. The participants also discussed the development of a website for Red Cross volunteers to be updated regularly. Lastly, the participants talked about the financial difficulties associated with playing their volunteering role. They proposed the development of a carpool system and/or financial assistance for transport. This aspect was highlighted as a pressing issue because of inflation being high and financial stress has increased. One participant shared how some people stopped volunteering because of increased economic pressures.

While those involved in the disaster response found it was very clear what their role was, those involved in the G&R program thought there was a lack of clarity on the scope and expectations regarding their work with local communities. This corroborates with the findings from the questionnaire-based survey. Furthermore, people highlighted that it was difficult to foster community participation as they were not always grounded at the local level and their work had limited visibility, which impacted on the attendance to meetings and broader participation of locals in disaster preparedness. Some of the participants felt that resources for equipment were lacking—this applied to both disaster preparedness and emergency response.

The FGD participants nonetheless saw different opportunities to improve their experience as volunteers and the work they do with local communities towards DRR. They stressed the importance of making the link between preparedness and response/recovery work that are often disconnected. This can be in the form of shared training and a platform for volunteers to be more connected. Half of those involved in community-led preparedness also thought it would be a good way to see tangible benefits through disaster response—this is not always the case with preparedness if no emergency happens. The other half, however, thought the G&R project gave them satisfaction as they could see development in their community regarding being more connected and being more prepared should a disaster occur. The participants explained the opportunity for sharing knowledge and experiences among volunteers coming from different parts of Aotearoa New Zealand, including in having lessons learned captured and best practices mainstreamed across multiple places, while retaining the local context. One participant said: “Travelling becomes an opportunity to share knowledge. A person living in Christchurch knows more about earthquakes than we know.” Overall, the volunteers were eager to be more connected and exchange regularly with others while learning or even being trained to lead community preparedness.

Lastly, the FGD ended with a self-reflection on how to support volunteers in their CBDRR activities. There was a consensus that volunteering is time consuming, can be overwhelming, and was becoming financially difficult under increased economic stress. The participants reiterated that a subsidy for travel would be helpful. They suggested the development of a system to provide free public transport to Red Cross volunteers, facilitating shared travel (that is, Uber Pool). The volunteers also proposed that they could get formal process to get time off from work to volunteer, particularly during emergencies. The participants also mentioned that financial and transport subsidies too can be offered based on the period of volunteering. Another important aspect raised includes community recognition for their service. The participants suggested that the volunteers could be offered a badge based on their volunteering period. The badge could display the service of volunteers in emergency and disaster management. More generally, they highlighted the need for recognition of Red Cross volunteer status, which could be a negotiation with the government, such as in providing volunteers with certain days per year to conduct their duty.

5 Discussion

The reasons to volunteer in G&R were linked to fostering positive changes towards disaster resilience, helping others be more prepared, and learning/strengthening skills. The choice of the NZRC was because of the reputation and the “standards” expected to volunteer for such an organization. Most volunteers have not experienced a disaster but feel concerned about disaster risk, want to help others and have an impact at the local level. This aligns with the literature that emphasizes that volunteering in disaster resilience actions is linked to the willingness of helping people and making a difference at the local scale (Hustinx et al. 2010; Haynes et al. 2020; Livi et al. 2020).

Volunteers’ training is essential for building long-term DRR capacity. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies is recognized as a leading organization in training volunteers for disaster response and recovery (Okita et al. 2023). The G&R volunteers thought the training was relevant, inclusive of different communities, and would recommend it to others. However, when it comes to coordinating CBDRR in their localities, they were not convinced they were well-equipped, had sufficient resources to coordinate CBDRR, nor that they had enough knowledge on how to foster community participation. Barbour and Manly (2016) who studied disaster volunteers in the United States pinpointed the differences between knowledge acquired though training and certification, versus its application in real life with contextual elements that require flexibility, adaption skills, and creativity to engage with local communities. Grant and Langer (2021) who examined volunteers in Fire and Emergency New Zealand found that the organization focused mainly on physical training to the detriment of more socially oriented training, which “downplayed the social and human side of skills and capabilities” (Grant and Langer 2021, p. 9). The G&R training is largely based on technical aspects (that is, what to do to be prepared in the face of emergencies), knowledge of tools available (that is, NZRC hazard App/First Aid App, PFA and CFA training), or the NZRC mission/goals. Empowering volunteers who wish to lead and coordinate community-based initiatives may thus entail both technical training and ongoing support on how to engage with local community members such group activities facilitation. Training should include cultural safety components related to Māori and minorities on ways to develop strong relationships prior to an emergency (Yumagulova et al. 2021).

Both FGD and questionnaires show that about half of the G&R volunteers were generally not clear about their role, which contrasted with those involved in disaster response and recovery (DWST) programs. While in emergencies there is a clear framework for volunteers to participate in the response, disaster preparedness is, in turn, looser, requiring working closely with people on local issues, which often differ from one community to another. A key challenge for the support agency relates to the tension between a program that provides flexibility to address contextual issues and fosters ownership of local communities in line with CBDRR principles, versus a prescriptive approach that is top-down with a standardized template that leaves little room for creativity and self-initiative (Simpson 2001; Haynes et al. 2020). Finding the right balance can be difficult and may require adequate level of support from implementing agencies, being able to adapt in function of certain situations with tailor-fit provision and resourcing (Anderson 2019; Bubb and Le De 2022). Beyond the standardized training currently provided by the NZRC, this might include offering a range of training/resourcing options that citizen volunteers and community members can choose from depending on their needs (Cull 2019), as well as the capacity to support and facilitate initiatives based on communities’ requirements.

Almost two thirds (60%) of the G&R volunteers had mixed views on whether the initiative contributed to fostering the preparedness of their local community. Tangible benefits were difficult to measure. This aspect is nonetheless critical, since one of the reasons for volunteers to join G&R is linked to “making a difference” and ultimately G&R is about strengthening communities’ resilience. Community participation is a process rather than an outcome, which makes it difficult to assess on an outcome-based basis. Furthermore, it is very difficult to evaluate the impacts of CBDRR until an emergency occurs (Cadag et al. 2018). In their systematic review of community engagement in disaster preparedness, Ryan et al. (2020) found that measurement and evaluation is a major knowledge gap. Simpson (2001) who focused on CERT in the United States, highlighted assessments of program impact as a key point that was largely missing. A recommendation may thus be for the NZRC to identify, with volunteers, ways to systematically monitor G&R impacts on preparedness. The research participants proposed evaluating community’s views on their preparedness, behavior change taking place, or counting the number of community members involved to assess if the CBDRR was successful.

The volunteers identified different barriers and limitations to G&R. They raised different issues to mobilize the wider community. The COVID-19 policies in Auckland restricted people from gathering in person, which affected the momentum for community engagement. While new technologies provide greater opportunities to foster CBDRR, in-person activities are indispensable to foster community participation. The participants thought DRR is not a priority compared with other more pressing issues, which makes it difficult to mobilize local community members. Research could investigate if this has changed with the recent floods and ex-tropical cyclone Gabrielle impacting Auckland in January and February 2023, which is outside the scope of this study. The level of community involvement is indeed critical and raises questions around the extent to which communities own and lead the G&R initiative central to successful CBDRR. Mitchell et al. (2010), who reflected upon CBDRR in the Northern region of New Zealand, found that community ownership and trust were critical elements of success. A danger is for community members to feel that a community-based approach is implemented by an outside organization (Delica-Willison and Gaillard 2012). Cadag et al. (2018) contended that to maintain trust and dialogue between actors, the participatory tools employed also need to be sustainable—in other words sustained and adapted to the local level by stakeholders who recognize (without being dependent upon) the contributions of external actors. The authors claimed that this generally succeeds best, and is sustainable, when local actors are actively involved in the conceptualization, implementation, and maintenance of participatory approaches and tools as part of CBDRR.

Another key finding relates to volunteers’ recognition of their contribution. A significant fraction of the volunteers did not necessarily feel valued or acknowledged for their work while also stressing it was becoming financially difficult to volunteer. They suggested being offered a volunteer badge and proposed a volunteer status with specific advantages. Recognition of volunteers’ contributions both internally and externally has been shown as critical element for keeping volunteers engaged and, by extension, the success of DRR (Mclennan et al. 2015; Whitaker et al. 2015), including in New Zealand during the 2011 Christchurch and 2016 Kaikoura earthquakes (Yumagulova et al. 2019). Many G&R volunteers mentioned the lack of visibility of the program, and by extension visibility of their actions. Cull (2019) highlights the importance of partnership with local and regional authorities while also gaining recognition from the public through knowledge sharing and hosting of regular DRR events. Simpson (2001) and later Carr and Jensen (2015) reported that a key success to CERT in the United States was linked to the official support received from FEMA, providing CERT with both more visibility and legitimacy. Moving forward, G&R could build upon existing, and/or develop, partnerships with local emergency management agencies such as through joint initiatives geared to disaster preparedness, public events, training, or exercises—this should, however, not happen to the detriment of local communities’ ownership over G&R nor duplicate existing efforts (WREMO 2024). There is also scope for the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) to work closely with G&R teams, since G&R fits very well with NEMA’s disaster resilience strategy and its goals to empower local communities in preparedness, response, and recovery (MCDEM 2019). Last, as part of the broader NZRC youth engagement strategy (NZRC n.d.), the G&R program could focus on engaging with youth in schools and universities (Rich and Kelman 2013) to empower younger generations for DRR.

6 Concluding Remark

Fast urbanization, poor planning, and growing inequalities coupled with the effects of climate change are increasing the disaster risk profile of large and medium-sized cities in Aotearoa New Zealand. The 2023 floods and ex-tropical cyclone Gabrielle are recent illustrations of the importance of community preparedness before any hazard or disaster happens. Local people are best placed to identify who is vulnerable in their locality, and what knowledge, skills, and resources are available and can be mobilized during disasters. It is indispensable for external DRR and emergency management agencies to actively work with local communities, not only during or after, but also before the occurrence of disasters. Initiatives like the G&R from the NZRC thus fill a critical DRR and emergency management gap. Leading, coordinating, and sustaining local community groups or bottom-up initiatives requires support from the top-down (Gaillard and Mercer 2013; Grant and Langer 2021). Our research showed that this means finding an equilibrium where volunteers and local communities are empowered and take ownership over the CBDRR process while being equipped with adequate skills through training and proper resourcing. It showed that technical oriented training is critical but that soft skills training such as coordinating, communicating, or facilitating activities at the local level are essential to successful CBDRR. The sustainability of volunteering in DRR also relates to being mindful of volunteers’ motivations and expectations, which implies a mix of tangible elements (that is, “volunteer days,” specific benefits/reward, or visible impacts) and more intangible aspects such as recognition of their work or meeting expectations. Beyond the G&R program, this research emphasized the need for a more systematic focus on CBDRR that supports citizen volunteering in disaster preparedness. This approach requires moving away from a culture of command-and-control and top-down disaster risk management towards recognizing and building upon local communities’ initiatives such as those motivated by helping others and strengthening community resilience.

Notes

Mural is a digital collaboration platform designed to facilitate teamwork by creating visual contents such as diagrams and flowcharts (https://www.mural.co/).

Qualtrics is an online platform offering comprehensive tools for creating surveys, collecting responses, and analyzing the data. It enables users to design detailed surveys, distribute them through various channels, and generate insightful reports from the collected data.

References

Anderson, B. 2019. Community driven development: A field perspective on possibilities and limitations. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University.

Bajek, R., Y. Matsuda, and N. Okada. 2008. Japan’s Jishu-Bosai-Soshiki community activities: Analysis of its role in participatory community disaster risk management. Natural Hazards 44(2): 281–292.

Bankoff, G. 2017. Living with hazard: Disaster subcultures, disaster cultures and risk-mitigating strategies. In Historical disaster experiences, ed. G.J. Schenk, 45–59. Cham: Springer.

Barbour, J.B., and J.N. Manly. 2016. Redefining disaster preparedness: Institutional contradictions and praxis in volunteer responder organizing. Management Communication Quarterly 30(3): 333–361.

Bubb, J., and L. Le Dé. 2022. Participation as a requirement: Towards more inclusion or further exclusion? The community disaster and climate change committees in Vanuatu as a case study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 76: Article 102992.

Cadag, J.R., C. Driedger, C. Garcia, M. Duncan, J.C. Gaillard, J. Lindsay, and K. Haynes. 2018. Fostering participation of local actors in volcanic disaster risk reduction. In Observing the volcano world: Volcano crisis communication, ed. C.J. Fearnley, D.K. Bird, K. Haynes, W.J. McGuire, and G. Jolly, 481–497. Cham: Springer.

Carr, J., and J. Jensen. 2015. Explaining the pre-disaster integration of community emergency response teams (CERTs). Natural Hazards 77(3): 1551–1571.

Chambers, R. 1994. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Analysis of experience. World Development 22(9): 1253–1268.

Cooke, B., and U. Kothari. 2001. Participation: The new tyranny?. London: Zed Books.

Cull, P. 2019. Community-based disaster response teams for vulnerable groups and developing nations: Implementation, training and sustainability. Master’s thesis. Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Delica-Willison, Z., and J.C. Gaillard. 2012. Community action and disaster. In Handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction, ed. B. Wisner, J.C. Gaillard, and I. Kelman, 711–722. London: Routledge.

Drabek, T.E., and D.A. McEntire. 2003. Emergent phenomena and the sociology of disaster: Lessons, trends and opportunities from the research literature. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 12(2): 97–112.

Gaillard, J.C., and J. Mercer. 2013. From knowledge to action: Bridging gaps in disaster risk reduction. Progress in Human Geography 37(1): 93–114.

Gaillard, J.C., J.R.D. Cadag, and M.M.F. Rampengan. 2019. People’s capacities in facing hazards and disasters: An overview. Natural Hazards 95(3): 863–876.

Grant, A., and E.R. Langer. 2019. Integrating volunteering cultures in New Zealand’s multi-hazard environment. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 34(3): 52–59.

Grant, A., and E.R. Langer. 2021. Wildfire volunteering and community disaster resilience in New Zealand: Institutional change in a dynamic rural social-ecological setting. Ecology and Society 26(3): Article 18.

Guijt, I., and M.K. Shah. 1998. The myth of community: Gender issues in participatory development. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Haynes, K., D.K. Bird, and J. Whittaker. 2020. Working outside “The Rules”: Opportunities and challenges of community participation in risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 44: Article 101396.

Heijmans, A. 2009. The social life of community-based disaster risk reduction: Origins, politics and framing. Disaster Studies Working Paper 20. Aon Benfield University College London Hazard Research Centre, London.

Heijmans, A., and L.P. Victoria. 2001. Citizenry-based and development oriented disaster response: Experiences and practices in disaster management of the citizens’ disaster response network in the Philippines. Center for Disaster Preparedness, Quezon City, Philippines.

Hustinx, L., F. Handy, R.A. Cnaan, J.L. Brudney, A.B. Pessi, and N. Yamauchi. 2010. Social and cultural origins of motivations to volunteer: A comparison of university students in six countries. International Sociology 25: 349–382.

Lalone, M.B. 2012. Neighbors helping neighbors: An examination of the social capital mobilization process for community resilience to environmental disasters. Journal of Applied Social Science 6: 209–237.

Le Dé, L., J.C. Gaillard, and W. Friesen. 2014. Academics doing participatory disaster research: How participatory is it?. Environmental Hazards 14(1): 1–15.

Livi, S., V. De Cristofaro, A. Theodorou, M. Rullo, V. Piccioli, and M. Pozzi. 2020. When motivation is not enough: Effects of prosociality and organizational socialization in volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 30: 249–261.

MacDougall, C., L. Gibbs, and R. Clark. 2014. Community-based preparedness programmes and the 2009 Australian bushfires: Policy implications derived from applying theory. Disasters 38(2): 249–266.

Maskrey, A. 2011. Revisiting community-based disaster risk management. Environmental Hazards 10(1): 42–52.

MCDEM (Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management). 2019. National disaster resilience strategy Rautaki ā-Motu Manawaroa Aituā. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Wellington, New Zealand.

McGee, T. 2011. Public engagement in neighbourhood level wildfire mitigation and preparedness: Case studies from Canada, the US and Australia. Journal of Environmental Management 92(10): 2524–2532.

McLennan, B.J., J. Whittaker, and J. Handmer. 2015. Community-led bushfire preparedness in action: The case of Be Ready Warrandyte. Melbourne, Australia: Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC.

Mitchell, A., B.C. Glavovic, B. Hutchinsony, G. MacDonald, M. Roberts, and J. Goodland. 2010. Community-based civil defence emergency management planning in Northland, New Zealand. Australasian Journal of Disaster Trauma Studies 2010(1): 1–10.

Moore, H.E. 1964. And the winds blew. Austin, Texas: University of Texas.

Nahkur, O., K. Orru, S. Hansson, P. Jukarainen, M. Myllylä, M. Krüger, M. Max, L. Savadori, et al. 2022. The engagement of informal volunteers in disaster Management in Europe. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 83: Article 103413.

NZRC (New Zealand Red Cross). n.d. Youth engagement strategy 2020–2030. https://www.redcross.org.nz/about-us/what-we-do/our-strategy/. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Okita, Y., S. Glassey, and R. Shaw. 2022. COVID-19 and the expanding role of international urban search and rescue (USAR) teams: The case of the 2020 Beirut explosions. Journal of International Humanitarian Action 7(1): Article 8.

Quarantelli, E.L. 1984. Emergent citizen groups in disaster preparedness and recovery activities. Final Project Report no. 33. Disaster Research Center, University of Delaware, Delaware, USA.

Rich, H., and I. Kelman. 2013. School emergency response training in Pueblo, Colorado (USA). In Disaster risk management – Conflict and cooperation, ed. S.R. Sensarma, and A. Sarkar, 58–84. New Delhi, India: Concept Publishing.

Ryan, B., K.A. Johnston, M. Taylor, and R. McAndrew. 2020. Community engagement for disaster preparedness: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 49: Article 101655.

Simpson, D.M. 2001. Community emergency response training (CERTs): A recent history and review. Natural Hazard Review 2(2): 54–63.

Titz, A., T. Cannon, and F. Krüger. 2018. Uncovering “community”: Challenging an elusive concept in development and disaster related work. Societies 8(3): 71–99.

Twigg, J., and I. Mosel. 2017. Emergent groups and spontaneous volunteers in urban disaster response. Environment and Urbanization 29(2): 443–458.

UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2015. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. https://www.unisdr.org/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Wenger, D.E., and J.M. Weller. 1973. Disaster subcultures: The cultural residues of community disasters. Preliminary paper 9. Disaster Research Center, University of Delaware, Newark, USA.

Whittaker, J., B. McLennan, and J. Handmer. 2015. A review of informal volunteerism in emergencies and disasters: Definitions, opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13: 358–368.

WREMO (Wellington Region Emergency Management Office). 2024. Hub guide. https://www.wremo.nz/get-ready/community-ready/community-emergency-hubs/find-your-hub/. Accessed 16 May 2024.

Yumagulova, L., S. Phibbs, C.M. Kenney, D.Y.O. Woman-Munro, A.C. Christianson, T.K. McGee, and R. Whitehair. 2021. The role of disaster volunteering in Indigenous communities. Environmental Hazards 20(1): 45–62.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) through the Resilience to Nature’s Challenges 2 for funding this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Le Dé, L., Ronoh, S., Kyu, E.M.T. et al. How Can Practitioners Support Citizen Volunteers in Disaster Risk Reduction? Insight from “Good and Ready” in Aotearoa New Zealand. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 15, 374–387 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00563-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00563-9