Abstract

Purpose of Review

To present a comprehensive overview regarding criteria, epidemiology, and controversies that have arisen in the literature about the existence and the natural course of the metabolic healthy phenotype.

Recent Findings

The concept of metabolically healthy obesity (MHO) implies that a subgroup of obese individuals may be free of the cardio-metabolic risk factors that commonly accompany obese subjects with adipose tissue dysfunction and insulin resistance, known as having metabolic syndrome or the metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO) phenotype. Individuals with MHO appear to have a better adipose tissue function, and are more insulin sensitive, emphasizing the central role of adipose tissue function in metabolic health. The reported prevalence of MHO varies widely, and this is likely due the lack of universally accepted criteria for the definition of metabolic health and obesity. Also, the natural course and the prognostic value of MHO is hotly debated but it appears that it likely evolves towards MUO, carrying an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality over time.

Summary

Understanding the pathophysiology and the determinants of metabolic health in obesity will allow a better definition of the MHO phenotype. Furthermore, stratification of obese subjects, based on metabolic health status, will be useful to identify high-risk individuals or subgroups and to optimize prevention and treatment strategies to compact cardio-metabolic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Kopelman PG. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature. 2000;404:635–43.

Wilson PW, D’Agoostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Kanell MB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1867–72.

Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J Chronic Dis. 1972;25:329–43.

Berrington de Gonzales A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2211–9.

Kissebah AH, Vydellinum N, Murray R, et al. Relation of body fat distribution to metabolic complications of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;54:254–690.

Despress JP. Body fat distribution and risk of cardiovascular disease: an update. Circulation. 2012;126:1301–13.

Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359.

Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 12:1595–607.

Kaur J. A comprehensive review of the metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Practice. 2014;2014:943162. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/933162.

Alberti KG, Zimmet P. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabete mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization. 1999;32–33.

Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III ). JAMA. 2001;285 : 2486–97.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52.

Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome-a new world-wide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059–62.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Eckel RH, et al. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2010;375:181–3.

Despress JP, Cartier A, Cote M, Arsenault BJ. The concept of cardio-metabolic risk: bridging the fields of diabetology and cardiology. Ann Med. 2008;40:514–23.

Draznin B. Mitogenic action of insulin: friend, foe or “frenemy”? Diabetologia. 2010;53:229–33.

Karelis AD, Brochu M, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Can we identify metabolically health but obese individuals (MHO)? Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:569–72.

Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS, et al. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2906–12.

Aguilar-Salinas CA, Garria EG, Robles L, et al. High adiponectin concentrations are associated with the metabolically healthy obese phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4075–9.

Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolgds K, et al. The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and normal weight with cardiovascular risk factor clustering: prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population ( NHANES 1999-2004). Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1617–24.

Stefan N, Katartzis K, Mahmann J, et al. Identification and characterization of metabolically benign obesity in humans. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1609–16.

Primeau V, Coderrev L, Karelis AD. Characterizing the profile of obese patients who are metabolically healthy. Int J Obes. 2011;35:971–81.

Karelis AD, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Inclusion of C-reactive protein in the identification of metabolically healthy but obese individuals. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34:183–4.

Ortega FB, Lee DC, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. The intriguing metabolically healthy but obese phenotype: cardiovascular prognosis and role of fitness. Eur Hear J. 2013;34:389–97.

Blundell JE, Dulloo AG, Salvador J, Fruhbeck G. Beyond BMI-phenotyping the obesities. Obes Facts. 2014;7:322–8.

van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Nuotio ML, Slagter SN, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolically healthy obesity in Europe: a collaborative analysis of ten large cohort studies. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:9.

Eckel N, Meidtner K, Kalle-Uhlmann T, Stefan N, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:956–66.

Shea JL, Randell EW, Sun G. The prevalence of metabolically healthy obese subjects defined by BMI and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Obesity. 2011;19:624–30.

Rey-lopez JP, deRezende LE, Pastor-Valero M, Tess BH. The prevalence of metabolically healthy obesity: a systematic review and critical evaluation of the definitions used. Obes Rev. 2014;15:781–90.

Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Are metabolically healthy overweight and obesity benign conditions?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:758–69.

• Eckel N, Li Y, Kuxhaus O, Stefan N, Hu FB, Schulze MB. Transition from metabolic healthy to unhealthy phenotypes and association with cardiovascular disease risk across BMI categories in 90 257 women (the Nurses’ Health Study): 30 year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:714–24 The authors report that a large proportion of metabolically healthy women converted to an unhealthy phenotype over time across all BMI categories, which is associated with an increased cardiovascular disease risk.

Hamer M, Bell JA, Sabia S, Batty GD, KIvimaki M. Stability of metabolically healthy obesity over 8 years; the English longitudinal study of ageing. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:703–8.

Soriguer F, Gutierrez R, Episo C, Rubio-Martin E, et al. Metabolically healthy but obese, a matter of time?: findings from the prospective Pizarra study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:145–51.

Bell JA, Hamer M, Sabia S, Singh-Manoux A, Batty GD, Kivimaki M. The natural course of healthy obesity over 20 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:101–2.

Kim H, Seo JA, Cho H, et al. Risk of the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in metabolically healthy obese people: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. Medicine. 2016;95:e3384.

Schroder H, Ramos R, Baena-Diez JM, et al. Determinants of the transition from a cardiovascular normal to abnormal overweight/obesity phenotype in a Spanish population. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:1345–53.

Hwang YC, Hayashi T, Fujimoto WY, et al. Visceral abdominal fat accumulation predicts the conversion of metabolically healthy obese subjects to an unhealthy phenotype. Int J Obes ( London). 2015;389:1365–70.

Stefan N, Haring HU, Hu FB, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1:152–62.

Phillips CM. Metabolically healthy obesity: definitions, determinants and clinical implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14:219–27.

Hinnouho GM, Czernichow S, Dugravot A, Nabi H, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M, et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and the risk of cardiovascular and type 2diabetes: the Whitehall II cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:551–9.

Twig G, Afek A, Derazne E, Tzur D, Cukierman-Yaffe T, Gerstein HC, et al. Diabetes risk among overweight and obese metabolically healthy young adults. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2989–95.

Aung K, Lorenzo C, Hinojasa MA, Haffner SM. Risk of developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease in metabolically unhealthy normal weight and metabolically healthy obese individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:462–8.

Appleton SL, Seaborn CJ, Visvanathan R, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the metabolically healthy obesity phenotype: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2388–94.

Rhee EJ, Lee MK, Kim JD, et al. Metabolic health is a more important determinant for diabetes development than simple obesity: a 4-year retrospective longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98369.

Bell JA, Kivimaki M, Hamer M. Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of incident type 2 diabetes :a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Obes Rev. 2014;15:504–15.

Jung CH, Lee MJ, Kang YM, et al. The risk of incident type 2 diabetes in Korean metabolically healthy obese population: the role of systemic inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:934–41.

Jung CH, Lee MJ, Kang YM, et al. Fatty liver index is a risk determinant of incident type 2 diabetes in a metabolically healthy population with obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:1373–9.

Khan UI, Wang D, Thurston RC, Sowers M, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Matthews KA, et al. Burden of subclinical cardiovascular disease in metabolically benign and at-risk overweight and obese women: the study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:179–86.

Marini MA, Succurro E, Frontoni S, Hribal ML, Andreozzi F, Lauro R, et al. Metabolically healthy but obese women have an intermediate cardiovascular risk profile between healthy non obese women and obese insulin-resistant women. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2145–7.

JJae SY, Franklin B, Choi YH, Fernhall B. Metabolically healthy obesity and carotid intima-media thickness: effects of cardio respiratory fitness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1217–24.

• Kang YM, Jung CH, Cho YK, et al. Fatty liver disease determines the progression of coronary artery calcification in a metabolically healthy obese population. PLoS One. 12:e0175762Obese individuals with fatty liver disease have an increased risk of atherosclerosis progression, despite. their healthy metabolic profile.

Christou KA, Christou GA, Karamoutsos A, Vatrtholomatos G, Gartzonika K, Tsatsoulis A, et al. Metabolically healthy obesity is characterized by a pro-inflammatory phenotype of circulating monocyte subsets. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2019;17:259–65.

Kip KE, Marrowquin OC, Kelly DE, et al. Clinical importance of obesity versus the metabolic syndrome in cardiovascular risk in women: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE ) Study. Circulation. 2004;109:706–13.

Song Y, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Ridker PM, Buring JE, Liu S. Comparison of usefulness of body mass index versus metabolic risk factors in predicting 10 year risk of cardiovascular events in women. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1654–8.

Dhana K, Koolhaas CM, van Rossum EFC, et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and the risk of vascular disease in the elderly population. PLoS One. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154273.

Hinnouho GM, Czemichow S, Dugravot A, et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: the Whitehall II cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:551–9.

Thomsen M, Nordestgaard BG. Myocardial infarction and ischemic heart disease in overweight and obesity with and without metabolic syndrome. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:15–22.

Chaleyachetty R, Thomas N, Toulias KA, et al. Metabolically healthy obese and incident cardiovascular disease events among 3.5 million men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1429–37.

• Mongraw-Chaffin M, Foster MC, Anderson CAM, et al. Metabolically healthy obesity in transition to metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;8:1857–65 The authors report that MHO at baseline is transient and that transition to metabolic syndrome (MetS) and duration of MetS explains heterogeneity in incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.

Fan J, Ong Y, Hui R, Zha W. Combined effect of obesity and cardiovascular abnormalities on the risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:4761–8.

• Zheng R, Zhou D, Zu Y. The long term prognosis of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality for metabolically healthy obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:1024–31. This meta-analysis of 22 prospective studies confirms a positive association between MHO phenotype and risk of CV events , but with not all-cause mortality.

Ortega FB, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Sui X, Blair SN, Lavie CJ. Role of fitness in the metabolically healthy but obese phenotype: a review and update. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;58:76–86.

Robertson LL, Aneni EC, Maziak W, et al. Beyond BMI: the “metabolically healthy obese” phenotype and its association with clinical/subclinical cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality-a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:14.

• Johnson W. Healthy obesity: time to give up the ghost? Ann Human Biol. 2018;45:297–8 A commentary in which the author takes a critical stand regarding the concept of healthy obesity.

• Stefan N, Haring HU, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: the low-hanging fruit in obesity treatment? Lancet Diabet Endocrinol. 2018;6:249–58 In this Series paper, the authors summarize available information about the concept of metabolically healthy obesity, highlight gaps in research, and discuss how this concept can be implemented in clinical care.

Trayhurn P. Endocrine and signaling role of adipose tissue: new perspectives on fat. Acta. Physiol Scand. 2005;184:285–93.

Frayn KN, Karpe F, Fielding BA, et al. Integrative physiology of human adipose tissue. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:875–88.

Ahima RS, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:327–32.

Havel PJ, Unger RH. Adipocyte hormones: regulation of energy balance and carbohydrate/lipid metabolism. Diabetes. 2004;53(supll 1):S 143–51.

Shaffer JE. Lipotoxicity: when tissues overeat. Curr Opin Lipidiol. 2003;14:281–7.

Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome-an allostatic perspective. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2010;18:338–49.

Unger RH, Scherer PE. Gluttony, sloth and the metabolic syndrome: a road map to lipotoxicity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:345–52.

Sims EA, Danforth E Jr, Horton ES, et al. Endocrine and metabolic effects of experimental obesity in man. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1973;29:457–96.

Garg A, Misra A. Lipodystrophies: rare disorders causing metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2004;33:305–31.

Moller DE, Kaufman KD. Metabolic Syndrome: a clinical and molecular perspective. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:45–62.

Heilbronn LK, Gan SK, Turner N, Campbell LV, Chisholm DJ. Markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism are lower in overweight and obese insulin-resistant subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1467–73.

Tchernof A, Despress JP. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:359–404.

Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. 2007;51:2005–11.

Szedroedi J, Roden M. Ectopic lipids and organ function. Curr Opin Lipidiol. 2009;20:50–6.

Heilbronn L, Smith SR, Ravusi E. Failure of fat cell proliferation, mitochondrial function and fat oxidation results in ectopic fat storage, insulin resistance and type II diabetes mellitus. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(Suppl 4):S12–21.

Chavez JA, Summers SA. Lipid oversupply, selective insulin resistance and lipotoxicity: molecular mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1801;2010:252–65.

Unger H, Go C, Scherer PE, et al. Lipid homeostasis, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome. Biochim Βiophys Acta. 2010;1801:209–14.

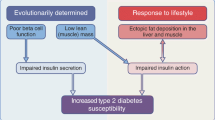

Katsoulis K, Paschou SA, Hatzi E, Tigas S, Georgiou I, Tsatsoulis A. The role of TCF7L2 polymorphism in the development of type 2 diabetes in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Hormones (Athens). 2018;17:359–65.

Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:175–84.

Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–30.

Matheson EM, Everett CJ. Healthy lifestyle habits and mortality in overweight and obese individuals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:9–15.

Smith SR, Dejonge L, Zachiwieja JJ, et al. Concurrent physical activity increase fat oxidation during the shift to a high-fat diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:131–8.

Pujja A, Gazzaruso C, Ferro Y, et al. Individuals with metabolically healthy overweight/obesity have higher fat utilization than metabolically unhealthy individuals. Nutrients. 2016;8:l.

Schleinitz D, Bootcher Y, Bluher M, et al. The genetics of fat distribution. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1276–86.

Gesta S, Bluher M, Yamamoto Y, et al. Evidence for a role of developmental genes in the origin of obesity and body fat distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6676–81.

Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, Winkler TW, Qi L, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist to hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010;42:949–60.

Andersen M, Karlsson T, Ek WE, et al. Genome-wide association study of body fat distribution identifies adiposity loci and sex-specific genetic effects. Nat Commun. 2019;10:339.

Waterland RA, Jitle RL. Early nutrition, epigenetic changes at transposons and imprinted genes and enhanced susceptibility to adult chronic disease. Nutrition. 2004;20:63–8.

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. The developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:183–7.

Mc Ewen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–9.

Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:259–84.

Bjorntorp P. Visceral fat accumulation: the missing link between psychological factors and cardiovascular disease? J Int Med. 1991;230:195–201.

Achilike I, Hazuda HP, Fowler SP, Aung K, Lorenzo C. Predicting the development of the metabolically healthy obese phenotype. Int J Obes. 2015;39:228–34.

Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS ) trial-a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Int Med. 2013;273:219–34.

Yang X, Smith U. Adipose tissue distribution and risk of metabolic disease: does thiazolidinedione-induced adipose tissue redistribution provide a clue to the answer? Diabetologia. 2007;50:1127–39.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Metabolism

Appendix

Appendix

Box 1 Definition criteria of MS

The definition of MS is based on clustering of metabolic abnormalities in the same individual. Different sets of criteria have been proposed by different health organizations. All versions included central obesity by waist circumference, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. The first formal definition was proposed by WHO that, in addition to the three common criteria, included evidence of insulin resistance (by IGT, IFG, or T2DM) [9]. In 2001, the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) proposed a new set of criteria, requiring for the diagnosis 3 of the following 5 parameters: abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, reduced HDL, hypertension, and fasting hyperglycemia [11]. Insulin resistance was not included in the criteria. In 2005, the international diabetes federation (IDF) and the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI), in an attempt to reconcile the different definitions, suggested waist circumference as prerequisite plus two of the criteria proposed by ATPIII for diagnosis [12]. There was a disagreement, however, regarding the definition of abdominal obesity by waist circumference threshold, and the IDF required a narrower waist circumference (WC) that would equate to BMI = 25 kg/m2, whereas the AHA/NHLBI required a larger WC threshold (BMI = 30 kg/m2) [13]. Recently, a unifying definition has been proposed by the IDF, AHA/NHLBI, WHO, International Atherosclerosis Society, and International Society for the Study of Obesity that includes 3 of the following 5 criteria: 1) elevated WC (specific thresholds based on population/country), 2) elevated serum TG (> 150 mg/dL) or medication, 3) reduced HDL (< 40 and < 50 mg/dL) in males and females, respectively, or medication, 4) elevated BP (systolic > 130, diastolic > 85 mmHg) or antihypertensive therapy, and 5) elevated fasting blood glucose (> 100 mg/dL) or medication [14]

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsatsoulis, A., Paschou, S.A. Metabolically Healthy Obesity: Criteria, Epidemiology, Controversies, and Consequences. Curr Obes Rep 9, 109–120 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00375-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00375-0