Abstract

Honey bees, Apis mellifera, have been implicated as vectors of plant pathogens. However, the survival of spores of plant pathogenic fungi through the digestive tract of workers has not been investigated. As workers defecate outside the hive, transport of hives could give rise to biosecurity concerns if fungal spores remain viable following passage through the digestive tract. To determine the likelihood that honey bees serve as vectors, this study investigated the viability of spores of Botrytis cinerea and Colletotrichum acutatum after passing through the digestive tract of summer and autumn worker bees. For both fungi, the mean viability of spores in faeces suspensions was less than one percent of the initial dose fed to the bees. Although survival was low, the large number of workers per hive implies a high probability of transmission of viable spores through honey bee faeces. Hence, in the case of economically important fungal diseases, transported hives could be a source of inoculum and quarantine restrictions should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) have been implicated as vectors of plant pathogens by several authors (Alexandrova et al. 2002a; Dedej et al. 2004; Gasparoto et al. 2017; Pattemore et al. 2014; Shaw 1999). Honey bees are known to disperse pathogens, such as the bacterium Erwinia amylovora (the causal agent of fire blight of apple and pear trees), from inoculum placed in hives to flowers, leading to the establishment of the bacteria on the surface of the stigmas and, consequently, infection (Johnson et al. 1993). In addition, E. amylovora can remain viable in beehives and on the bee’s body for over 24 h, on pollen for 72 h and for a period of 36 h in the bee’s intestine (Alexandrova et al. 2002b). In Europe, these findings have led to the implementation of biosecurity restrictions associated with the transport of beehives to prevent the long-distance transport of the pathogen (e.g. EC Plant Health Directive, 2000/29/EC). Additionally, spores of Austropuccinia psidii, the causal agent of myrtle rust, survived in honey bee hives and on the body of workers for at least 9 days after they had been experimentally inoculated (Pattemore et al. 2018). These authors provided evidence that myrtle rust spores are brought to the hives by foragers, even when there were no signs of workers actively collecting spores, and neither the hive environment nor the grooming behaviour of the bees killed or removed the spores. In addition to the suggestion by Pattemore et al. (2018) that spores of A. psidii could survive in hives for extended periods of time and that long distance movement of hives needs to be considered as a potential risk for the transmission of myrtle rust spores to other locations, it is likely that the transmission of plant pathogens could also occur between neighbouring crops within the forage range around a hive.

While attention has been given to the presence of plant pathogenic bacteria and fungi on the body of honey bees, the survival of fungal spores after consumption and passage through the digestive tract has not been studied. However, species of yeasts commonly found in nectar can survive and coexist in the gastrointestinal tract of bumble bees during several weeks of winter hibernation when the availability of flowers is severely reduced, thereby using the gastrointestinal tract as a reservoir (Pozo et al. 2018). Although Pozo et al. (2018) did not show the routes and rates by which yeasts are transmitted from the gastrointestinal tract of bumble bees to flowers in the following spring, this may involve a faecal route. Faecal transmission of viruses has been demonstrated (Ribière et al. 2007), but the faecal transmission of plant pathogenic fungi is as yet unstudied, and there is limited information on whether the transport of hives could lead to the dispersal of plant pathogenic fungi between regions.

It has been documented that honey bees actively collect spores of phytopathogenic fungi and transport them to the hives (Shaw 1999) or to other flowers (Altizer et al. 1998). As workers defecate outside of the hive (Winston 1991), consumption of such spores could raise a biosecurity concern if they remain viable in the hives and survive through the digestive tract of honey bee workers. This is particularly important for generalist phytopathogenic fungi, such as Botrytis cinerea and Colletotrichum acutatum, which cause disease on a wide range of horticultural crops (Adaskaveg and Hartin 1997; Hatcher 1995; Williamson et al. 2007).

Therefore, this study aimed to (i) investigate the viability of spores of B. cinerea and C. acutatum after passage through the digestive tract of honey bee workers and (ii) estimate the probability of honey bees dispersing spores of plant pathogenic fungi through their faeces. This information is crucial to understand this potential pathway of plant disease transmission by honey bees and whether the movement of hives for crop pollination purposes poses a potential biosecurity threat in terms of spread of plant pathogenic fungi.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of bees

Feeding experiments were conducted in mid-February and late March of 2018 using summer and autumn workers, respectively. These two types of workers were chosen because environmental factors related to season can influence the worker’s metabolism due to changes in the levels of microbiocidal enzymes in the digestive tract (Orčić et al. 2017), which could damage or digest fungal spores. For each experiment, newly emerged workers were obtained by placing brood frames with late stage pupae, originating from three hives, in an incubator in the dark at 34 °C and approximately 50–70% relative humidity (Hatjina et al. 2013). Colonies were kept at the Waite Campus, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, and were regularly inspected for symptoms of disease. Newly emerged workers contain few or no bacteria in their gut (Martinson et al. 2012) and acquire gut microbes by feeding on the supplies in the comb and contact with its surfaces or by trophallaxis of nectar with older foragers (Powell et al. 2014). Therefore, workers were collected directly after emergence to minimize potential contamination. Equal numbers of workers were collected from each comb.

Individuals were harnessed in 500-μL plastic centrifuge tubes by placing a paper collar between their heads and thoraces (Hori et al. 2006). Small amounts of cotton wool were placed at the bottom of each tube to support the weight of the abdomen. Preliminary experiments showed that this support prolonged survival of the harnessed workers. The tubes containing the workers were placed in a tube holder and incubated in the conditions described above.

2.2 Feeding experiment

Bees were fed in the morning and afternoon for 3 days. As newly emerged workers have poor learning and memory performance (Masson and Arnold 1984), on the first, day bees were fed by using a sterile needle to gently unfold their probosces and offered 50% sucrose solution. As demonstrated by Behrends and Scheiner (2009), after 24 h of conditioning, a few workers began to show response to gustatory stimuli and were subsequently fed using the proboscis extension reflex method (Bitterman et al. 1983; Takeda 1961); others were fed as described above. Only bees that participated in all feeding schedules were used in the experiment. Each worker received 10 μL of 50% sucrose solution containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20 with or without fungal spores at the concentration of 106 spores/mL at each feeding time. This amount of liquid is less than their average daily intake of 33 μL (Decourtye et al. 2003) and was chosen to prevent early defecation. In the control treatments, workers received sterile sucrose solution only. Each treatment and control consisted of 21 bees.

The concentration of fungal spores administrated to the bees was based on the amount of colony forming units (CFU) of plant pathogens found on bees foraging on infected flowers, which commonly ranges from 103 to 106 CFU per bee (Dedej et al. 2004; Pattemore et al. 2014).

2.3 Preparation and assessment of spore suspensions

Two plant pathogenic fungal species were used in the bioassays, Botrytis cinerea (CBS 140599) and Colletotrichum acutatum (EU670080), which had been isolated from grape and almond, respectively. The isolates were obtained from the plant pathology laboratory of the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, University of Adelaide. Mycelia were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco) in 9-cm diameter Petri plates at 25 °C under cool white fluorescent and black light with a photoperiod of 12 h for 10 days. Cultures were established on three consecutive days to generate suspensions with spores of the same age in sterile sucrose solution, the latter to provide a source of carbohydrates for the workers. Spores were harvested by flooding the cultures with 15 mL of sterile 50% sucrose solution containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20 and dislodging spores from the mycelia using a sterile plastic spreader. The resulting suspensions were filtered through three layers of sterile cheesecloth to remove any hyphal fragments present (Scheuerell and Mahaffee 2006). The concentration of spores in each initial stock suspension was determined using a Neubauer haemocytometer and a compound microscope, and the suspension diluted with 50% sucrose solution to obtain the target concentration. To determine the viability of spores, aliquots of 0.1 mL of the dilution 1:1000 of spore suspension in sucrose solution were spread onto three replicate plates of PDA and incubated as described above. CFU were counted 36 h after plating. Suspensions were prepared using fresh cultures every day.

2.3.1 Faeces collection and plating

Approximately 24 h after the bees were last fed, the faeces were collected by placing the abdomen of individual bees over a sterile 1.5 mL tube and gently applying pressure to the abdomen (Bailey et al. 1983; Ribière et al. 2007). Prior to faeces collection, individual workers were surface disinfected for 1 min using 1% sodium hypochlorite solution to remove any superficial contaminants, and then rinsed three times in 1 mL of sterile water. A volume of 1 mL of sterile water containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20 was added to each tube containing faeces. The suspensions of faeces for each bee were vortexed for 1 min, and three replicate aliquots of 0.1 mL from each tube were spread on PDA medium containing streptomycin sulfate (50 mg/L) and chloramphenicol (250 mg/L) in 9-cm diameter Petri plates and incubated as described above. The antibiotics were used to inhibit the growth of bacteria. To control for surface contamination, the final rinse from the surface disinfection was also collected and plated in the same manner. After 36 h, CFU were determined for all plates. Additionally, the faecal material of a group of 21 newly emerged workers that had not participated in any of the feeding schedules was collected and plated as described above to assess the initial microbial composition of the intestinal contents of the newly emerged workers. None of the bees used in the experiments defecated naturally during the period of 3 days.

2.4 Confirmation of identity of fungal isolates

In order to ascertain the identity of the colonies obtained from plates spread with the faeces suspensions, representative colonies were transferred to PDA amended with streptomycin sulfate (50 mg/L) and incubated for 10 days at 25 °C. To obtain pure cultures, plates were flooded with sterile water containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20, and spore suspensions were prepared as described above. Aliquots of 0.1 mL of each suspension were spread over reverse osmosis water agar (20 g/L, Difco) in a Petri dish. After 8 h, single-germinating spores were located using a dissecting microscope in a laminar flow cabinet and transferred to three replicate plates of PDA and incubated at 25 °C under cool white fluorescent and black light for 10 days as described previously.

Mycelia were collected by scraping the surface of single spore–derived cultures using a sterile scalpel. DNA was extracted and purified using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The spacer regions ITS1 and ITS2 were amplified and sequenced using the primers ITS1 and ITS4 (White et al. 1990).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out with 2 μL DNA (25 ng/μL), 8.5 μL nuclease-free water, 1 μL of each primer and 12.5 μL GoTaq Colorless Master Mix 2x (Promega, USA) in a total volume of 25 μL. The PCR cycles consisted of 2 min initial denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 1 min of denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min of annealing at 55 °C and 1 min of elongation at 72 °C and a final 10 min elongation at 72 °C. PCR was performed in a TC-512 thermal cycler (Techne, UK). PCR amplification products were analysed by electrophoresis at 110 V for 30 min in a 2% agarose gel containing 0.003% nucleic acid–staining solution (GelRed, Intron Biotechnology) in 1 × Tris borate EDTA buffer and viewed under UV light. PCR products were purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System kit (Promega, USA) and sent to the Australian Genome Research Facility for bidirectional Sanger sequencing. The forward and reverse sequences were edited using Geneious software version 9.1.4 (Kearse et al. 2012). Consensus sequences were compared with sequences deposited in GenBank using the basic local alignment sequence tool (BLAST) (Boratyn et al. 2013). The GenBank sequences of the original isolates were also selected and aligned with the sequences obtained from this study.

2.5 Data analysis

All statistical analyses were executed in R version 3.3.2 (R-Project 2019). Normality and homoscedasticity assumptions were tested for all variables by QQ plot and Shapiro test and by Bartlett test, respectively. The daily data for the viability of spore suspensions of B. cinerea and C. acutatum in 50% sucrose solution were subjected to generalized linear models (GLM) with binomial error distribution. Data for survival of spores of B. cinerea and C. acutatum in honey bee faeces during summer and autumn were log transformed and analysed using linear models. The ggplot2 package was used for plotting the figures (Wickham 2011).

The probability of dispersal of spores of plant pathogenic fungi through honey bee faecal matter can be estimated by P = 1 − (1 − p)(tmn), where p is the probability of a bee carrying a viable spore, t is the average number of trips per bee, m the number of workers per hive, and n the number of hives leading to the probability of at least one viable spore being transferred through honey bee faecal matter.

3 Results

None of the controls, i.e. (i) the intestinal contents of newly emerged workers that did not participate in either feeding experiment, (ii) the suspensions from the last rinses of bees and (iii) the sterile sucrose solutions used to feed bees in the control treatments, yielded microorganisms that would grow on PDA containing antibacterial antibiotics in the conditions imposed.

The spores of both fungi had a mean viability of greater than 85% in 50% sucrose solution (Figure 1). There was a significant difference between days in the viability of spores in the suspensions used to feed summer bees (B. cinerea, \( {X}_2^2 \)=32.42, P < 0.01; C. acutatum, \( {X}_2^2 \)= 38.45, P < 0.01) but not in the suspensions used to feed autumn bees (B. cinerea, \( {X}_2^2 \)=1.06, P > 0.05; C. acutatum, \( {X}_2^2 \)=0.04, P > 0.05).

Viability of spores of Botrytis cinerea and Colletotrichum acutatum in 50% sucrose solution used to feed summer (a) and autumn (b) workers over 3 days. Colony forming units were determined on potato dextrose agar amended with streptomycin sulfate (50 mg/L) and chloramphenicol (250 mg/L). The lower-case letters indicate significance (generalized linear binomial model, P < 0.05) among the suspensions for each fungus.

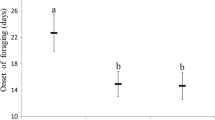

No colonies of B. cinerea and C. acutatum grew on the plated faeces of bees that had been fed sterile sucrose solution containing Tween 20. There were significant differences in the survival of spores through the digestive tract between the seasons and fungal species (F(3, 80) = 12.32, P < 0.001, Figure 2). Survival of spores through the digestive tract was significantly higher for autumn workers than for summer workers (B. cinerea, F(1,40) = 5.30, P < 0.05; C. acutatum, F(1, 40) = 0.22, P < 0.01), and the mean number of CFUs of C. acutatum in faeces suspensions was significantly greater than B. cinerea for both summer (F(1, 40) = 5.88, P < 0.05) and autumn bees (F(1, 40) = 11.81, P < 0.05). There was no evidence of proportion changes for the survival of B. cinerea and C. acutatum among the seasons (F(1, 80) = 2.66, P > 0.05). Overall, less than one percent of the conidia in the initial dose fed to the bees over a period of 3 days resulted in colonies on PDA supplemented with antibacterial antibiotics.

Abundance (CFU, colony forming units) of Botrytis cinerea and Colletotrichum acutatum in diluted faeces of summer and autumn workers fed with 106 spores/mL of either fungus. CFU were determined on the potato dextrose agar plates amended with streptomycin sulfate (50 mg/L) and chloramphenicol (250 mg/L). Control treatments are not shown as no colonies arose from the faeces of workers fed with sterile sucrose solution. Upper-case letters indicate significant differences between the fungal species for each season and lower-case letters indicate significant difference between the seasons for each fungal species (linear model, P < 0.05).

The predominant fungal colonies isolated from the faeces of the bees resembled B. cinerea and C. acutatum in morphology and were confirmed to be identical to those provided in the feeding suspensions. In addition, in the experiment with summer bees, single colonies of Aspergillus sp. were detected from the faeces of two workers and a single colony of Penicillium sp. was detected from the faeces of a single worker that received suspensions of B. cinerea. Furthermore, a single colony of Penicillium sp. was detected from the faeces of a single worker that received suspensions of C. acutatum. In the experiment with autumn bees a single isolate of Cladosporium sp. was detected from the faeces of a worker from the C. acutatum treatment. The sequences generated by PCR ranged from 297 to 513 bp in length, and the accession numbers are given in the supplementary files (Table S1).

Given that defecated spores had a viability of approximately 1%, the probability of dispersal of spores of plant pathogenic fungi through honey bee faecal matter, P, approaches 1 when 1, 10 or 100 workers from multiple hives foraging in an area consume 6 × 104 spores (Figure 3).

4 Discussion and conclusions

Spores of two common plant pathogenic fungi, B. cinerea and C. acutatum, can survive passage through the digestive tract of honey bee workers for at least 24 h, and viable spores have a high probability of being dispersed through faecal matter. These findings concur with the report by Alexandrova et al. (2002b) that the bacterium E. amylovora remained viable in the workers’ intestines 36 h after initial contamination. The period of time for which propagules of plant pathogens remain viable in the intestines of workers is critical as the duration of transport of hives between crops and regions is typically less than 24 h. In addition, there is potential for long range dispersal due to migratory beekeeping practices, which extend to distances of up to 4500 km in the USA (Simone-Finstrom et al. 2016) and 1400 km in Australia (Benecke 2003).

Although the survival of plant pathogen propagules through the digestive tract of workers will be affected by conditions such as pH, osmotic pressure, enzymes and oxygen and nutrient availability imposed on the spores in the digestive tract (Dillon and Charnley 1991), it is likely that the majority of the spores were digested. In honey bees, enzymes such as the antioxidant superoxide dismutase and glutathione S-transferase are known to have microbiocidal activity (Nikolenko et al. 2011). The activity of these enzymes is influenced by environmental factors associated with different seasons, and in winter workers, their levels decrease (Korayem et al. 2012; Orčić et al. 2017). This may explain the larger proportion of spores that survived in autumn than in summer bees which could, consequently, increase the risk of infection of autumn or winter flowering crops such as almonds and canola. Nevertheless, it is possible that different outcomes would have been obtained if the experiments had been conducted using older workers as their gut microbiota (Martinson et al. 2012) could potentially enhance or interfere with digestion of fungal spores.

In healthy bee colonies, workers will defecate outside their hives. In theory, this could spread spores of plant pathogenic fungi over a typical forage range of 5 km from the hive (Beekman and Ratnieks 2000) if workers feed on spores or infected food sources and the spores survive through their digestive tract. Such vectoring of generalist plant pathogenic fungi through faeces could affect agricultural and natural systems as these species of fungi can cause disease in a large range of host plants, including almond, apple, citrus, stone fruit and strawberry (Adaskaveg and Hartin 1997; Hatcher 1995; Williamson et al. 2007). Furthermore, dispersal of viable spores would occur even if only a small percentage of spore-fed bees defecate, because of the large number of bees per hive, the number of hives per unit area and the number of foraging trips made by each bee. As a single spore can induce infection in favourable conditions (Deverall and Wood 1961), if foragers and nurse bees feed on an infected food source in or outside of the hive, dispersal of viable spores through faeces is a near certainty in common pollination scenarios where 100 or more hives are moved from one location to another. However, the incidence of contamination through hive transport depends on whether the spores can cause infection on plants after defecation. While such investigation was beyond of the scope of our study, it needs to be considered for future work.

The survival of spores of plant pathogenic fungi other B. cinerea and C. acutatum has not, to our knowledge, been documented. Of particular concern for Australia is Austropuccinia psidii, the causal agent of myrtle rust, which is considered a biosecurity threat (Berthon et al. 2018; Carnegie et al. 2016; Westaway 2016). Honey bees are known to actively collect rust spores (Chapman 1964; Shaw 1990) and have been observed collecting urediniospores of Puccinia psidii (since renamed Austropuccinia psidii) from infected plants in Australia (Carnegie et al. 2010). Spores of A. psidii and many other plant pathogenic fungi typically are spread by wind, often many kilometres from the initial infected area (Makinson 2018). Movement of honey bee hives may pose a potential pathway for the spread of myrtle rust against the prevailing wind direction and beyond its current distribution along the eastern seaboard and the North Territory of Australia. As noted by Pattemore et al. (2014), little can be done to manage the transport of plant pathogens within the foraging range of a hive, but quarantine restrictions associated with movement of bee hives from currently infected to uninfected areas should be considered.

Spores of B. cinerea and C. acutatum in 50% of sucrose solution showed high viability when plated on PDA (i.e. > 80%). However, limited variability (approximately 10%) was observed among the suspensions used to feed summer bees, which might reflect genetic variation resulting from the multinucleate nature of spores of B. cinerea (Roper et al. 2011), which could translate into differences in viability in the conditions imposed. Similarly, several species in the genus Colletotrichum can occasionally produce multinucleate spores (TeBeest et al. 1989). In addition, although the colonies used in this study were of the same age and were maintained in the same conditions, it is possible that some spores had reduced viability such that they failed to germinate within 36 h.

This research was conducted using microbiological culture methods, which has the advantage of providing quantitative results that take into account the viability of the spores that survive through the digestive tract of honey bee workers and grow in the conditions imposed. By contrast, molecular techniques such as real time PCR would have quantified both viable and non-viable spores. Apart from implications for biosecurity and epidemiology, the findings that the majority of fungal spores consumed lose their viability inside the gut, combined with the information that honey bee workers collect fungal spores, may indicate that these spores are digested and are an alternative nutrient source for bees. Large scale experiments are needed to further understand the complexities of the interactions among different species of microorganisms in the digestive tract of honey bee workers, to determine how different factors influence the survival of spores in the digestive tract of honey bees, for how long workers will continue to produce infective faeces after initial contamination and whether honey bee hives can serve as long term reservoirs of phytopathogenic fungi.

References

Adaskaveg, J.E., Hartin, R.J. (1997) Characterization of Colletotrichum acutatum isolates causing anthracnose of almond and peach in California. Phytopathology 87, 979–987. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto.1997.87.9.979

Alexandrova, M., Cimini, B., Bazzi, C., Carpana, E., Massi, S., Sabatini, A.G. (2002a) The role of honeybees in spreading Erwinia amylovora. Acta Hortic 590, 55–60

Alexandrova, M., Porrini, C., Bazzi, C., Carpana, E., Bigliardi, M., Sabatini, A.G. (2002b) Erwinia amylovora longevity in beehives, beehive products and honeybees. Acta Hortic 590, 201–205

Altizer, S.M., Thrall, P.H., Antonovics, J. (1998) Vector behavior and the transmission of anther-smut infection in Silene alba. Am. Midl. Nat. 139, 147–164

Bailey, L., Ball, B., Perry, J. (1983) Association of viruses with two protozoal pathogens of the honey bee. Ann. Appl. Biol. 103, 13–20

Beekman, M., Ratnieks, F.L.W. (2000) Long-range foraging by the honey-bee, Apis mellifera L. Funct. Ecol. 14, 490–496. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2000.00443.x

Behrends, A., Scheiner, R. (2009) Evidence for associative learning in newly emerged honey bees (Apis mellifera). Anim. Cogn. 12, 249–255

Benecke, F.S. (2003) Commercial beekeeping in Australia. A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Coorporation. RIRDC Publication, ACT, Australia

Berthon, K., Esperon-Rodriguez, M., Beaumont, L., Carnegie, A., Leishman, M. (2018) Assessment and prioritisation of plant species at risk from myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) under current and future climates in Australia. Biol. Conserv. 218, 154–162

Bitterman, M., Menzel, R., Fietz, A., Schäfer, S. (1983) Classical conditioning of proboscis extension in honeybees (Apis mellifera). J. Comp. Psychol. 97, 107–119

Boratyn, G.M. et al. (2013) BLAST: a more efficient report with usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W29–W33. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt282

Carnegie, A.J., Lidbetter, J.R., Walker, J., Horwood, M.A., Tesoriero, L., Glen, M., Priest, M.J. (2010) Uredo rangelii, a taxon in the guava rust complex, newly recorded on Myrtaceae in Australia. Australas. Plant Pathol. 39, 463-466

Carnegie, A.J., Kathuria, A., Pegg, G.S., Entwistle, P., Nagel, M., Giblin, F.R. (2016) Impact of the invasive rust Puccinia psidii (myrtle rust) on native Myrtaceae in natural ecosystems in Australia. Biol. Invasions 18, 127–144

Chapman, G. (1964) Urediospore collections by honey bees from Puccinia psidii. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 57, 264

Decourtye, A., Lacassie, E., Paham-Delegue, M. (2003) Learning performances of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) are differentially affected by imidacloprid according to the season. Pest Manag. Sci. 59, 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.631

Dedej, S., Delaphane, K.S., Scherm, H. (2004) Effectiveness of honey bees in delivering the biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis to blueberry flowers to suppress mummy berry disease. Biol. Control 31, 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2004.07.010

Deverall, B.J., Wood, R.K.S. (1961) Infection of bean plants (Vicia faba L.) with Botrytis cinerea and B. fabae. Ann. Appl. Biol. 49, 461–472

Dillon, R.J., Charnley, A.K. (1991) The fate of fungal spores in the insect gut. In: Cole TG, Hoch CH (eds) The fungal spore and disease initiation in plants and animals. Plenum Press, New York and London, 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2635-7

Gasparoto, M.C.G., Lourenco, S.A., Tanaka, F.A.O., Sposito, M.B., Marchini, L.C., Silva, G.J., Amorim, L. (2017) Honeybees can spread Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides among citrus plants. Plant Pathol. 66, 777-782. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12625

Hatcher, P.E. (1995) 3-Way interactions between plant pathogenic fungi, herbivorous insects and their host plants. Biol. Rev. 70, 639–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1995.tb01655.x

Hatjina, F., Papaefthimiou, C., Charistos, L., Dogaroglu, T., Bouga, M., Emmanouil, C., Arnold, G. (2013) Sublethal doses of imidacloprid decreased size of hypopharyngeal glands and respiratory rhythm of honeybees in vivo. Apidologie 44, 467–480

Hori, S., Takeuchi, H., Arikawa, K., Kinoshita, M., Ichikawa, N, Sasaki, M., Kubo, T. (2006) Associative visual learning, color discrimination, and chromatic adaptation in the harnessed honeybee Apis mellifera L. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 192, 691–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-005-0091-4

Johnson, K.B., Stockwell, V.O., Burgett, D.M., Sugar, D., Loper, J.E. (1993) Dispersal of Erwinia amylovora and Pseudomonas fluorescens by honey bees from hives to apple and pear blossoms. Phytopathology 83, 478–484. https://doi.org/10.1094/Phyto-83-478

Kearse, M. et al. (2012) Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649

Korayem, A.M., Khodairy, M.M., Abdel-Aal, A.-A.A., El-Sonbaty, A.A. (2012) The protective strategy of antioxidant enzymes against hydrogen peroxide in honey bee, Apis mellifera, during two different seasons. J. Biol. Earth Sci. 2, 93–109

Makinson, R.O. (2018) Myrtle rust in Australia - a draft action plan, presented at the Plant Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre’s National Science Exchange. Melbourne, Australia

Martinson, V.G., Moy, J., Moran, N.A. (2012) Establishment of characteristic gut bacteria during development of the honeybee worker. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 2830–2840

Masson, C., Arnold, G. (1984) Ontogeny, maturation and plasticity of the olfactory system in the workerbee. J. Insect Physiol. 30, 7–14

Nikolenko, A.G., Saltykova, E.S., Gaifullina, L.R. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of antioxidant protective processes in honeybee Apis mellifera. In: Farooqui T & Farooqui AA (eds) Oxidative stress in vertebrates and invertebrates: molecular aspects of cell signaling. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 279–293

Orčić, S. et al. (2017) Seasonal variation in the activity of selected antioxidant enzymes and malondialdehyde level in worker honey bees. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 165, 120–128

Pattemore, D.E., Goodwin, R.M., McBrydie, H.M., Hoyte, S.M., Vanneste, J.L. (2014) Evidence of the role of honey bees (Apis mellifera) as vectors of the bacterial plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Australas. Plant Pathol. 43, 571–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13313-014-0306-7

Pattemore, D.E., Bateson, M., Buxton, M., Pegg, G., Hauxwell, C. (2018) Assessment of the risks of transmission of myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) spores by honey bees (Apis mellifera). A Plant & Food Research report prepared for: Ministry for Primary Industries

Powell, J.E., Martinson, V.G., Urban-Mead, K., Moran, N.A. (2014) Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of Apis mellifera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 7378–7387

Pozo, M.I., Bartlewicz, J., van Oystaeyen, A., Benavente, A., van Kemenade, G., Wäckers, F., Jacquemyn, H. (2018) Surviving in the absence of flowers: do nectar yeasts rely on overwintering bumblebee queens to complete their annual life cycle? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, fiy196

Ribière, M., Lallemand, P., Iscache, A.L., Schurr, F., Celle, O., Blanchard, P., Oliver, V., Faucon, J.P. (2007) Spread of infectious chronic bee paralysis virus by honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7711-7716. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01053-07

Roper, M., Ellison, C., Taylor, J.W., Glass, N.L. (2011) Nuclear and genome dynamics in multinucleate ascomycete fungi. Curr. Biol. 21, R786–R793

R-Project (2019) R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, 1.2.1335 edn. Vienna, Austria

Scheuerell, S.J., Mahaffee, W.F. (2006) Variability associated with suppression of gray mold (Botrytis cinerea) on geranium by foliar applications of nonaerated and aerated compost teas. Plant Dis. 90, 1201–1208

Shaw, D.E. (1990) The incidental collection of fungal spores by bees and the collection of spores in lieu of pollen. Bee World 71, 158–176

Shaw, D.E. (1999) Bees and fungi, with special reference to certain plant pathogens. Australas. Plant Pathol. 28, 269-282. https://doi.org/10.1071/ap99044

Simone-Finstrom, M., Li-Byarlay, H., Huang, M.H., Strand, M.K., Rueppell, O., Tarpy, D.R. (2016) Migratory management and environmental conditions affect lifespan and oxidative stress in honey bees. Sci. Rep. 6, 32023

Takeda, K. (1961) Classical conditioned response in the honey bee. J. Insect Physiol. 6, 168–179

TeBeest, D., Shilling, C., Riley, L.H., Weidemann, G. (1989) The number of nuclei in spores of three species of Colletotrichum. Mycologia 81, 147–149

Westaway, J.O. (2016) The pathogen Myrtle Rust ('Puccinia psidii') in the Northern Territory: First detection, new host and potential impacts. NT Nat 27, 13

White, T.J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., Taylor, J. (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications. 18, 315–322

Wickham, H. (2011) ggplot2 Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics. 3, 180–185

Williamson, B., Tudzynsk, B., Tudzynski, P., van Kan, J.A.L. (2007) Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00417.x

Winston, M.L. (1991) The biology of the honey bee. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Tijana Petrovic and Dr Ricardo Feliciano dos Santos for guidance with laboratory work, the Adelaide Scholarships International (ASI) scheme for supporting the first author and the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine for operating support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JBP: design and execution of the experiment, data analyses, and writing; ESS, KH: experimental design, technical assistance, and manuscript editing; RC: data analyses and manuscript editing; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Manuscript editor: Cedric Alaux

Survie et probabilité de transmission de champignons pathogènes des plantes par l'appareil digestif des abeilles ouvrières.

Apis mellifera / champignons pathogènes des plantes / fèces d'abeilles / quarantaine / Botrytis cinerea / Colletotrichum acutatum.

Überlebensfähigkeit und Übertragungswahrscheinlichkeit von pflanzenpathogenen Pilzen im Verdauungstrakt von Honigbienen-Arbeiterinnen.

Apis mellifera / pflanzenpathogene Pilze / Honigbienen-Kot / Quarantäne / Botrytis cinerea / Colletotrichum acutatum.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Parish, J.B., Scott, E.S., Correll, R. et al. Survival and probability of transmission of plant pathogenic fungi through the digestive tract of honey bee workers. Apidologie 50, 871–880 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00697-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00697-6