Abstract

Chinese companies are far from taking control over African or global mining. In 2018, they control less than 7% of the value of total African mine production. Chinese investments in African mining of non-fuel minerals between 1995 and 2018 have contributed to production growth but it has also increased Chinese control over African mineral and metal production. There is evidence pointing to a continued Chinese expansion in African minerals and metals but at a slower pace than in the past decade. Through a detailed analysis of every mine, fully or partially controlled by Chinese interest in Africa and all other parts of the world the paper also measures total Chinese control over global mine production to be around 3% of the total value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Africa’s resources have been a tempting target for adventurers, kings, traders, governments and companies for centuries. The European imperial powers dividing Africa at the end of the nineteenth century spurred a scramble for African resources with horrifying consequences for Africans and their societies (Diogo and van Laak 2016).

Although Africa has a mining and metallurgy tradition going far back, it was only with the diamond and gold rushes in southern Africa that Africa’s minerals resources came into focus (Yachir 1988). During the twentieth century, European and North American interests dominated African mining, with a short interlude of increased national control following independence and nationalisations in the middle of the century. In the early twenty-first century, a new scramble for Africa seemed to start (Southall and Melber 2009). The quick growth of Chinese mineral demand and the vast untapped resources of Africa attracted Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) into exploration and mining when domestic resources were no longer sufficient.

Sinosteel’s acquisition of the Dilokong chromite mine in 1997 marked the start of Chinese investment into African mining. This was not, however, the first contact between African and Chinese miners. In 1904, in the aftermath of the Boer wars, the shortage of labourers on the South African gold mines was acute. In the next two years, a total of 64,000 indentured Chinese workers were imported to South Africa. In 1906, they represented 34% of the total number of unskilled workers on the mines.

The Chinese workers were treated as an international commodity and stayed on a three-year contract with conditions in principle similar to the African migrant labour. In 1907, the risk of having a large group of Chinese workers as immigrants when their contract ended made the Chinese question a key issue in the elections in Transvaal. The Boer generals Smuts and Botha won the elections, and all the Chinese workers were repatriated to China after their contracts ended. By 1910, all of them had been shipped home (Allen 1992).

It took almost 100 years for the next Chinese mine workers to arrive in South Africa.

Serious worries about the new Chinese companies’ behaviour on the African and global mining scene, and the effects of their entry, have been voiced. From sensational and exaggerated statements like “the Chinese appear determined to pull all available levers, .... China’s resource undertaking is global and among the most aggressive in history,” (Moyo 2012 p. 3)Footnote 1 to academic research carefully studying various aspects of Chinese mining activities (for example: Cooke et al. 2015; Deng 2013; Kaplinsky and Morris 2009; Morgan 2019; Sautman and Hairong 2019).

The cartoon in Fig. 1 illustrates the new situation—as it appears superficially and is generally presented in media: China is taking control over mineral resources in Africa, where the dominance of European and North American mining companies has been unchallenged for 150 years. It is, however, not possible to compare the slicing up of Africa by colonial powers and transnational mining companies in the twentieth century with Chinese presence today. The political situation with independent African states, new mining technology and public scrutiny and awareness of environmental and social issues caused by mining make it impossible for a Chinese mining company to act like Anglo American, Newmont or Union Minière did during much of the twentieth century.

Cartoon of Chinese investors in African mining. Cartoon by Kevin KAL Kallaugher, The Economist, Kaltoons.com

In order to gauge Chinese geopolitical influence in an area of such basic economic importance as security of mineral supply, it is crucial to get a correct understanding of the scale of Chinese mining overseas. Without an up-dated and fine-tuned view of Chinese control over mineral production globally, and in Africa specifically, any attempt to serious and realistic discussion becomes difficult. Our study shows firstly that Chinese control over mine production, in Africa and globally, is much smaller than generally anticipated,Footnote 2 and has evolved slowly, and evidently without any master plan, over the past 20 years. Secondly, that the concept of a ‘China Inc’, a coordinated Chinese government–led attempt to control flows of minerals to China is a simplification.

The aim of this paper is three-fold:

-

To measure Chinese control over global and African non-fuel mineral production.

-

To monitor the development of this Chinese control over time.

-

To analyse which companies are active and how they interact with Chinese state interests.

The basis for the analysis is a mine by mine database built over more than 25 years monitoring all mines in the world: production, ownership and other details not only for Chinese companies but also for all companies (Raw Materials Data; Ericsson 2011). A detailed understanding of the size and extent of control by Chinese companies of mine production around the world forms the scientific basis for discussion of all other effects of these mining activities. The social, environmental and political consequences of Chinese investments and control over mine production are dealt with in many studies, on all Africa (Cheru and Obi 2010; Burgis 2015; Wegenast et al. 2017) or on specific aspects in certain countries where some studies are highly critical (Human Rights Watch 2011), while others compare Chinese practices with those of non-Chinese companies and come to the conclusion that there is not much difference (Jansson et al. 2009 p. 39; Sautman 2015; Sautman and Hairong 2012).

These important topics are outside the scope of the present study. This paper starts with a review of Chinese overseas mining investments worldwide to give a background to the activities in Africa. A presentation of the most important Chinese companies engaged in overseas exploration projectsFootnote 3 and mining follows. We analyse in more detail the growth of Chinese control over African mining. We discuss what are likely future developments of Chinese control over global and African mine production. Finally, we make some observations about the effects of the entry of Chinese companies onto the global mining scene for international metal markets, African countries and Chinese domestic mining operations. A detailed description of Chinese mining investments into Africa is given in Online resource 1.

Methodology

Ownership and control

Who controls a company, its owners, its managements, its lenders? These questions have attracted the interest of economists and other scientists since almost a hundred years (Berle Jr and Means 1929; Gogel and Koenig 1981; Demsetz and Lehn 1985). Control can be exercised in many ways of which ownership is the most basic and direct one. Other ways of exercising control over a company include, for example, through administrative and technical management, interlocking directorates, long-term contracts, market knowledge, proprietary technology, infrastructure, financing and vertical integration. The importance of these different ways of controlling a company varies considerably between branches of industry and from time to time within the same branch.

In this and previous studies, we have defined control in the mining industry the following way: “To be in control is to have the possibility to act decisively on strategically important issues rather than day-to-day influence over a company. Such issues include the broad policies of a company, decisions on large investments, buying or selling of subsidiaries and authority to appoint or dismiss top management” (Tegen 1994; Ericsson and Tegen 2016). In the global mining industry, ownership—either majority holding or partial ownership sometimes through joint ventures—is by far the most common way of controlling a mine and its production. In the middle of the twentieth century, management contracts were an important feature in control over the large South African mining industry and hence of global mine production. With the decline of South African share of global mine production, this is no longer the case (Ericsson and Tegen 1988).

A second important issue is how to make a quantitative assessment of control over a mine or a mining company using all the potential control mechanisms listed above? This is virtually impossible, and instead we assume, with good reason, that ownership and control are closely correlated in the mining sector. When measuring ownership, and translating it to control, it is sometimes done mathematically in proportion to equity share. This method leads, however, to certain problems: It overestimates the influence of small dispersed unidentified share holdings and, inversely, underestimates the real power of large shareholders, perhaps being themselves mining companies. Furthermore, it leaves some part of a mine’s production out of anybody’s control as small shareholders obviously do not exert any control. Instead, we have used a model described in Who owns who in mining (Raw Materials Group 1997). A detailed matrix with crucial limits at 50, 20 and 10% of ownership and several combinations of the number of owners is employed to determine the level of control.Footnote 4

Our focus is control by Chinese companies, which poses additional problems in that many of them are state-controlled. The general problems of control over state-owned companies in the mining sector have been dealt with in detail by Radetzki. He concludes that also in this specific case that “Given the ambiguities of the control concept… [Radetzki’s study] relies entirely on equity ownership as the measuring rod” (Radetzki 1985 p. 19). There are certainly some specific characteristics of the Chinese model of control over production of mineral resources and mine production, which are covered qualitatively below in the “Discussion” section, that should ideally be taken into account when quantifying such Chinese control, but also, to determine Chinese control over mine production outside China, we use the equity ownership as a useful proxy for control for the same reasons as above.

Our measure of control and its developments over time give the possibility to monitor the long-term effects of Chinese political strategic plans and Chinese companies’ investments measured as what physical volumes of ores and metals are actually produced and imported to China or sold on global markets. These volumes are the end results of political pressures, capital investments and operational expenses. These physical amounts of ores and concentrates are what the Chinese government and the Chinese companies ultimately are trying to control and get hold of, to cover the demand in China and make necessary profits.

Companies and governments regularly make optimistic announcements of long-term new investment projects and financing schemes. But what really become of these plans, if mines are being built and jobs created, is only evident after a number of years. In the meantime, politicians, journalists and analysts make optimistic or pessimistic exaggerations and understatements depending on what they want to attain or prove. The general economic situation and political feelings at the time of an investment or when a deal is concluded are often given too much weight in their analysis. Some of these problems are avoided by using the methods we have chosen.

The mining database Raw Materials Data (RMD 2014) has been used as a starting point to identify producing mines all around the world with Chinese ownership, excluding mines in China, from 1990 to 2013.Footnote 5 This picture has been updated to 2018 based on information from a wide range of sources—including corporate annual reports, press releases, the international mining press, academic studies and daily newspapers.

Control over the production from each of the identified mines has been determined by employing the method described above, and dividing the production according to the ownership situation. For example, if there are two identified shareholders, A and B, each having 30% of the shares, with other shares being dispersed among a large number of owners with each holding a small number of shares, control is considered to be divided 50/50 between A and B, the same ratio as between the shareholding of A and B, 30/30. In this way no production is left outside any company’s control. All mine production of each mine or company is in the final step allotted to the controlling companies in relation to their control share at the end of each year.

In order to include all minerals and metals in the analysis, the value of the controlled production has been calculated at the mine stage based on annual average prices. In this way, the value of production of all minerals and metals can be added up and an aggregate picture obtained. This illustrates control over production of all minerals and metals, and is measured as a percentage of the total global value of all mineral and metal production at the mine stage.

Access to relevant and correct data is in general not a major problem for research focusing on ownership and production in the mining sector when dealing with companies that are publicly owned or operating in market economies. Many of the major listed Chinese companies also provide sufficient information. It is, however, frustrating that often, but not always, when a company or an operation becomes majority-controlled by Chinese interests, it is getting more difficult, and sometimes impossible, to obtain correct and reliable information on ownership and production. We are however confident that we have captured sufficiently detailed information on almost all mines which have been operating and wholly or partly controlled by Chinese owners between 1995 and 2018. We have collected data during more than two decades, and we are aware of that in spite of this detailed approach, we have missed a number of mines with limited production volumes. The marginal effects of these volumes not included are discussed later in the paper.

This study deals exclusively with non-fuel minerals, i.e. minerals and metals excluding coal, oil and natural gas.Footnote 6 The steps following after mining in the value chain, smelting and refining, are sectors which have also attracted some Chinese interest. Investments in these sectors are however more limited, and we have not included them in our analysis.

At the time of writing (in mid-2019) there were no complete 2018 production statistics. We have used 2018 production figures as far as they have been available. To get a figure for world total value production in 2018, we have supplemented missing data with 2017 production figures and used average prices for 2018. Production volumes are relatively stable but prices are more volatile and have a stronger influence on changes in the value of production between years and hence this is a way to get a reasonably correct preliminary world total figure for 2018.

Chinese mining investments globally

Before the global financial crisis in 2008/2009, Chinese overseas mining investments remained below US dollar (USD) 5 billion annually, during most years, according to Chinese statistics (China National Bureau of Statistics 2020) (see Fig. 2). In the early 2010s, investments for most years reached between USD 10–15 billion with a peak of USD 25 billion in 2013. Investments over the following years dropped significantly and were recorded as negative in 2017.Footnote 7 This is hard to reconcile with the fact that the same year China, Moly acquired Tenke Fungurume and Yancoal C&A in Australia for a total of around USD 8 billion, and there was also other deals and investments.Footnote 8 Even if the figures are said to include both investments in projects and acquisitions of companies as well as divestments they underline the difficulties of relying upon Chinese statistics.

Chinese investments were driven mainly by three factors:

-

The growing demand for metals in the exceptionally long and persistent Chinese economic boom

-

High metal prices attracting Chinese investors’ interest for pure commercial reasons

-

Government policies inspiring/ordering and supporting outward FDI

It is possible to divide the gradual Chinese expansion into global mining into a few major periods with evolving Chinese policies and global metal markets’ status.

Pre 2000

The Chinese process to privatise state-owned enterprises had started in the 1990s and laid the foundation for expansion abroad (Green and Liu 2005). The Chinese expansion overseas to secure access to minerals started as a trickle in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Sinosteel and Baosteel, both major Chinese state-owned steel companies, took minority stakes in two Australian iron ore mines: Channar (1990) and Eastern Range (1995).Footnote 9 These deals were modelled on the Japanese participation, with minority stakes against long-term contracts made in the early 1970s also in Western Australia, when the Japanese steel industry was booming (Wilson 2012).

The first mine, of any significant size, which was acquired 100% by a Chinese company was the Marcona iron ore mine in Peru, which was privatised in 1992. It is logical that the first Chinese overseas mining investments were made in iron ore as the steel industry is an important motor in early industrialisation phases and particularly so in China, that followed a socialist—state-led development model—putting special emphasis on heavy industry expansion.

2000–2005

The Going Global policy to support the internationalisation of the Chinese economy, the ‘zou chu qu’ (literally ‘go out’), was announced in the early 2000s and extended to mining in 2003/2004 (Jansson 2011). The Chinese economic and industrial structure with large state-owned enterprises, which were encouraged to lead the way, facilitated the overseas expansion. In addition, the Chinese financial sector, under close government control, supported the investments with low-cost loans and other financial arrangements.

2006–2013

The so-called Super Cycle, the unparalleled and persistent increase in metal demand between 2005 and 2012, was fuelled by the dramatic Chinese economic growth (Humphreys 2015). It led to rapidly increasing costs for imported ores. Efforts by Chinese authorities to reduce prices of iron ore by influencing existing price setting mechanisms failed. Taking control of overseas mines seemed an alternative to reduce vulnerability and dependence on metal world markets (Hurst 2017). Chinese interest in foreign mineral deposits and mines became a continuous affair in this period. State-owned companies, whether small or large, whether controlled by central or provincial government; companies eager to secure their supply of raw materials; private companies of different sizes and shapes wanting to reap easy profits from increasing metal prices; all jumped the bandwagon.

2014 and onwards

The success rate of Chinese projects improves learning from the mistakes made in the previous period. After 2015, Chinese mining investments have been reduced in line with a more cautious attitude to mining FDI by the Chinese leadership, and because of weaker growth in Chinese metal demand. The global investment climate for additional mining capacities disappeared almost completely (Weinland 2019).

Total Chinese overseas mining investments from 2003 to 2017 were around USD 125 billion according to Chinese statistics, representing some 14% of total Chinese FDI over the same period. Other sources give USD 43 billion for the period 2013–2017 (Farooki 2018), USD 53 billion for the period 2011–2016 (von Hartlieb-Wallthor and Marbler 2017) and USD 111 billion between 2005 and 2019 of which USD 28 billion from 2013 to 2017 (China Global Investment Tracker 2020) compared with the USD 56 billion for 2014–2016 given in Fig. 2.Footnote 10 The figures are not identical but of the same order of magnitude, probably an indication that they are reliable for our purpose. The total stock of mining investment was 158 billion USD in 2017, some 9% of the total stock of investments (Schüler-Zhou et al. 2019 p. 59).

Total mining investments globally in the same years are estimated at around USD 2700 billion (RMG Consulting 2015). It is difficult to measure investments, in particular to avoid double counting in large projects extending over many years. It is, however, possible to conclude that Chinese FDI has always played a limited role on the global scene. A maximum in Chinese mining FDI came in 2013 one year after the global peak and reached a 7% share of total global mining investments, in most years the share was below 5%.

All mines controlled by Chinese owners, which we have identified and which have been producing in the period 1995–2018, are listed in Table 1. Some mines which have been producing only in the years in between the ones highlighted in Table 1 are also included. Finally, a few major projects, which are close to completion at present, are in the list. The data includes the name of the deposit/project/mine, short name of the Chinese company involved,Footnote 11 its ownership share and the year of the acquisition or start of the project. If an acquisition was made in several distinct steps, there are two or more years noted. The main metals produced, stage of development in 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2013 and 2018, are noted.

The number of overseas operating mines, which was controlled by Chinese interests remained at a low level until 2007. In 2005, there were still just 13 operating mines under Chinese control and only three in the late engineering/construction phase. Five years later, in 2010, another 15 mines had started production and 24 projects were at various stages of development. The years around 2010/11 were the peak of the Super Cycle and Chinese investors were very busy. In 2010 alone, eight new mines started operating. In total, in 2013, we could identify around 60 mines globally controlled by Chinese interests.

There are most certainly additional mines, also controlled by Chinese investors, which we have not been able to identify due to lack of information. This is particularly true for the countries bordering China, including North Korea, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Laos, Myanmar, Mongolia, the Philippines, Russia and Vietnam, mines in these countries can easily export smaller volumes by ship, truck or train to China. Our figures might hence underestimate Chinese control, but the difference should be minimal as the missing mines are likely to be small.

We have made an estimate of the value of production from all the mines we have missed based on an analysis of figures of Chinese imports and export from host countries with known exports to China. There could, of course, be Chinese-controlled mine production in other countries, but these mines would likely be very small, with marginal effects on total Chinese control.

The metals of most significance are iron ore, bauxite and nickel. If we assume that 50% of all unidentified production in these countries is controlled by unknown Chinese companies, the total additional amounts under control of Chinese companies would be not more than 5–6 Mt iron ore, 4–5 Mt bauxite and 50 kt nickel contained in ores with a total value of around USD 1 billion, which equates to 0.15% of the total global value of mine production. This figure will not materially affect our discussions or alter the conclusions.

The developments over time, the geographical distribution of the operating mines, and the metals mined in 2005 and 2018 are shown on maps in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4.

Three main geographical areas, in which Chinese expansion has taken place, can be identified:

-

Around the Pacific Rim including, Australia, Canada, and in more recent years, Latin America

-

Southern Africa and, recently, West Africa

-

In the neighbouring countries including Mongolia, Lao, North Korea, Myanmar and Tadjikistan, Vietnam (Andrews-Speed et al. 2016).

Australia and Southern Africa are the most important target areas for Chinese mining investments. There are two main reasons for this: firstly, they are major mining countries/regions with large resources in particular of iron ore and copper which are in focus for Chinese investors and there are plenty of investment opportunities, secondly they are geographically relatively close to China. In addition, particularly in Australia, there is a vibrant junior mining community and many investors with an appetite for risky exploration and mining projects. The stock exchange in Johannesburg does not have as many listed junior exploration and mining companies as has the ASX exchange in Sydney. There is, however, a host of mining companies, exploration and construction service companies and experts of all professions needed in exploration and mining in South Africa, and it is still the most important entry point to all of southern Africa. It was the final steps of the Zambian privatisation process which raised Chinese interest in Africa in the late 1990s. Australia came into focus during the Super Cycle years from the mid-2000s to mid-2010s. A range of Chinese companies, both private and state-owned, were caught by the general enthusiasm, and invested in Australian projects.

In the rest of the world, it took longer for Chinese companies to establish contacts, find projects and start making investments. In the past few years, however, a couple of large-scale projects in Latin America have started production.

Chinese investors have been particularly interested in three metals: iron ore, copper and gold. In 2018, there were 10 iron ore mines, 20 copper mines (some of them also producing cobalt) and 14 gold mines operating and wholly or partially controlled by Chinese investors. There were further 2 zinc/lead and 4 bauxite mines. All other minerals/metals: chromite, lithium, manganese, nickel, niobium, phosphate, PGM and uranium, taken together accounted for the remaining 10 mines.

The value of mine production controlled by Chinese investors outside of China was USD 21.5 billion in 2018. Copper together with cobalt accounts for USD 8.0 billion, making them by far the most important metals. Iron ore USD 4.9 billion is the second most important metalFootnote 12 followed by gold and bauxite USD 1.9 and 1.4 billion respectively. Bauxite, the raw material for aluminium, accounts for only 7% of the total value, but is the fastest growing metal, increasing by 14 times from 2014.

Chinese control over iron ore has declined over the period and was at a peak in 2014; since then, a number of marginal iron ore mines controlled by Chinese investors have been forced to suspend their operations. Iron ore mines controlled by Chinese owners have further not managed to increase their production at the same pace as their competitors. The Chinese interests in gold have been increasing steadily over the period after a slow start, and around 2010, the first mines (in Laos and Tadjikistan) became operational.

The distribution of metals controlled reflects the demand situation in China quite well in that the demand for iron ore and copper concentrates to feed Chinese steel works and copper smelters are huge. In the past five years, bauxite has become an important target for Chinese investment, with growing aluminium production in China. The interest in gold is probably partly due to the fact that gold mines can be relatively small and hence do not require large investments neither in plants and equipment nor in transport facilities. Chinese private investors seem to have been attracted by the aura and potential profitability of gold mining, and Chinese demand for gold has also been increasing in the past decade.

Metal demand in China was the key factor behind the choice of metals the Chinese investors have made. It seems, however that often opportunity, rather than reason, has guided the selection of specific investment targets. Countries where Chinese companies may have had previous business contacts or experiences seem to dominate. Many of the deposits/mines have been small. Several of the mines acquired had been previously closed down were on care and maintenance and/or had a chequered history in various other ways which was reflected in an attractive price.

In some cases, the country risks had been considered exceedingly high by the major transnational mining companies or the previous owners had a poor reputation. Such factors have not always dissuaded Chinese investors. The situation also reflects the limited technical and managerial experiences in large-scale mining in general among Chinese mining companies when the overseas expansion started in the early 2000s (Humphreys 2015). Furthermore, they are late-comers to the international mining scene, and most of the really attractive mines and known deposits have already been brought under the control of the major international mining companies or national companies with strong local political backing. In addition, the Chinese companies were probably not fully aware of the difficulties and risks when investing in mining projects in foreign countries. Previously, they had been operating in a relatively easily manageable investment climate in China where a strong government could facilitate and minimise regulatory delays, environmental demands were less stringent, and capital was easily available.

The entry of Chinese companies onto the global mining stage has not been without hiccups. It was only after learning from a number of not-so-profitable and even failed projects that the growth started in earnest. With the benefit of hindsight, the results of many of the early investments, in particular in Australia, have been mixed at best. In summary, the Chinese could only invest in what was up for sale if they wanted to quickly increase control over imported minerals and metals, and the Going Global policy made it clear that this was politically desirable.

The growth of Chinese companies’ control over metal/mineral production (outside of China) has been slow (see Fig. 5), from a tiny fraction during the late 1990s and early 2000s (0.1–0.2%) to around 0.8% in 2014 and increasing to 3% in 2018. As a comparison, in 2013, Australian companies controlled almost 10% and Canadian 8% of the total value of global non-fuel mine production, two to three times more than companies from China. Control by Chinese companies was initially surprisingly low considering China’s large import dependence compared with other countries and also the huge amounts of money spent every year on imports. The Chinese growth has accelerated with the acquisition of interests in a couple of major mines, such as Las Bambas and Toromucho in Peru and Tenke Fungurume in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Chinese control of overseas mine production 1995–2018 (% of total value of world mine production). Source: Table 1

Exploration and mining projects are high-risk ventures. Some of the Chinese projects have stalled and ran into serious problems for a range of reasons—rather like many exploration and mining projects do. Some of these projects, which for whatever reason, never got off the ground, are listed in Table 2. The purpose of the list is to be transparent with which projects and mines we have excluded from our calculations and also to give an indication of potential future addition to Chinese-controlled production if some of the projects would finally succeed.

The most common reasons for delay are poor profitability due to falling metals prices and/or rising costs. In some cases, Chinese ownership level was below our 10% cut off; in others, we have not been able to elucidate what has really happened to a Chinese investment. In 2017, it was estimated that as many as 40% of the Chinese-controlled overseas assets were considered as “inactive” (Farooki 2018 p. 9).

A few major, potentially game-changing deals, which could have given Chinese investors a kick-start when entering the global scene, never materialised. Already in 2004, state-owned China Minmetals, mostly known as a trading company exporting rare earths and other Chinese speciality minerals, launched a hostile bid for a Canadian company Noranda, which was a global major and among the ten largest mining companies in the world. This bid was seen as an assault on the Canadian national patrimony, and the Canadian government made it clear that the proposed deal would not be allowed to go through. The bid was called off by Minmetals.

A second mega deal, which would have given Chinese interests control over a large share of global mine production, was attempted in 2008/2009 (Humphreys 2015 pp. 144–147). Aluminum Corporation of China (Chinalco), the Chinese major state-controlled aluminium company,Footnote 13 started machinations to create a global alliance with Rio Tinto, which was - and is - one of the top three companies in global mining. Chinalco saw an opportunity to create a world-leading resource company with strong Chinese participation. The two companies would start a range of joint ventures and development projects. It could have become a win-win deal, with Chinalco in one move getting access to Rio Tinto’s advanced technologies and international network of mines and projects, and Rio getting closer to the rapidly growing Chinese demand for metals. Rio would further get a much needed financial injection from Chinalco and the Chinese banks backing it. The alliance was stopped, however, in June 2009 by opposition from Rio’s shareholders and from Australian authorities.

Not all proposed deals met with such opposition. In the same period, when the global financial crisis was still at its peak, Canadian base metals miner Teck was in deep trouble. But Chinese sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation (CIC) came to the rescue and paid USD 1.5 billion in a private placement of Class B shares of Teck for a 17% stake in the ailing company. The company’s founder and chairman Norman B. Keevil wrote in its 2009 annual report under the heading “Appreciation”: “To CIC, which invested in Teck at an important time for us last July, we appreciate your confidence and are more than pleased that it proved profitable for you so quickly. China is an important market for our business and we look forward to the opportunity to work with you to strengthen our position in the market for our mutual benefit.” (Keevil 2010).

Chinese companies active in overseas mining

The Chinese entities controlling mine production around the world in the period 1995–2018 represent a wide variety of companies, public and private, big and small, state-owned by central government or provincial authorities, and there are also government institutions such as the China-Africa Development Fund (CADF). Individual, private Chinese traders and small-scale artisanal miners have established themselves in some countries. The most important companies are included in Table 3. From the very largest such as Aluminum Corporation of China Ltd. (Chalco) listed on the New York, Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges, and fully state-controlled entities such as China-Africa Development Fund and China National Nuclear Corporation, to private, small- and medium-sized companies and private individuals and businessmen.

The companies can be divided into five main groupsFootnote 14:

-

1.

Artisanal and small-scale private operators

-

2.

Small companies, mostly privately held, with small but industrially operated mines

-

3.

Medium-sized companies, private or state-owned with mines of all types

-

4.

Major companies, mostly state-owned, operating world class projects

-

5.

Steel companies, securing access to iron ore

The companies in each group have different backgrounds and vary not only in size and scale of their operating mines but also in their interaction with the Chinese state, their main business goals and ambitions for the future and their modus of operation. The groups do not have exact boundaries, but the division gives a better understanding of the wide spectrum of Chinese companies in mining.

Naturally, the first group does not have any identified entities, and its members are not represented in Table 3. The Chinese small-scale miners of gold around the world , for example, in Ghana (Hirsch 2013) and of cobalt/copper in the DRC (Jansson et al. 2009; BGR 2019) operate as small-scale miners in general, simple operations often lacking necessary permits and potentially with serious environmental and health and safety effects. They are profit-driven and completely outside of any Chinese state control, rather their activities often cause problems for Chinese authorities. Their total combined production is small and does not add up to more than limited volumes controlled, except possibly in cobalt as discussed below.

The second group consists of Chinese companies, mostly without Chinese state backing, optimistically investing during the Super Cycle in order to profit from the Chinese metal demand, mostly without any deep understanding of the mining industry but with some personal contacts in countries like South Africa and Australia where opportunities were easily available, companies such as China Hongqiao Group mining bauxite in Guinea, and China International Fund Ltd. with a failed iron ore project in the same country, Taung Gold International running a marginal gold project, the Jeanette mine in South Africa, without success for many years and Hong Kong–based Snow Peak International investing in suspended Australian base metal mines struggling to get them back into stable and profitable operation. Most mines are relatively small but in general operated according to standards accepted in each host country. The share of ownership is often small and management is sometimes left to local staff.

The third group is more heterogenous. The common denominator is closer links to Chinese government and Chinese capital supply. There are companies such as Bosai which have carefully and successfully expanded into bauxite mining in Africa and Latin America based on its experiences from mining in China. The cobalt producer Huayou with operations in DRC, and Tinaqi focusing on lithium and China Overseas Uranium in Namibia are other examples. These companies are carving out a niche in the international market for specific metals and have excellent links into the Chinese markets for their products.

China Railway Construction Corp is not primarily interested in the mining business itself but to engineer and construct mines and related infrastructure. Some Chinese companies, as for example China Shanghai Corporation for Foreign Economic & Technological Cooperation (China SFECO Group), are combining within the same corporate group, mining operations with mine construction and specialised engineering skills and production of mining equipment.

The fourth group are state-owned companies with clear ambitions to become major actors on the international mining scene: Zijin, China Moly, Minmetals and CITIC. They have built on their experiences from mining and trading in China and gradually learnt from activities overseas since the early 2000s. They have been under watch from Beijing but have also attracted international capital to build their businesses and are forced to adhere to international operational standards. They are also under scrutiny by international NGOs. Chinese companies of the fourth group are likely, in the not too distant future, to become more or less equal in skills to the traditional transnational companies in both mining and engineering and highly competitive. Minmetals formed the Mineral and Metals Group (later renamed MMG) in 2009 when it had acquired the main assets from listed Oz Minerals. MMG was completely open when it set its “aspirational growth target to build the next generation’s leading global diversified minerals and metals company” (Michelmore and Zhou 2010).

The final group are steel companies primarily interested in securing their supply of iron ore trying to limit their exposure to the volatility of global iron ore and other steel raw material prices. They were among the first Chinese overseas investors into mining and have in general been more successful than many other Chinese ventures. They are financially robust and have strong state backing, often have mining experiences of their own and have left management to the other JV partners.

The size of the Chinese companies active abroad varies, but even the largest are relatively small compared with the major international mining companies of the world. Measured by its share of the total value of controlled mine production of all metals in 2018 the largest Chinese company is Minmetals which controls 0.5%; Hunan Valin 0.3%; China Molybdenum, Zijin Mining and CITIC each controls around 0.2%, while Chalco follows at around 0.15%. By comparison, iron ore and copper mining alone (not including its control over other metals and minerals) gave BHP control over 4.1% of the total value of mine production—making this company around 10 times larger than the biggest Chinese mining company.

Chinese geology and history of central government limiting the growth of mining enterprises in order to prevent potential political opposition has contributed to, in an international comparison, small mines and a fragmented corporate structure (Golas 1999; Diogo and van Laak 2016 pp. 190–191; Humphreys 2015 p. 85; Trust Fund Project 2005). The mining industry included state-owned enterprises with central, provincial and local ownership together with large number of mining cooperatives and small-scale entities. This was the structure of the Chinese mining industry when demand for metals and minerals grew in the end of the 1990s and is an important explanation why Chinese companies still today are relatively small. The sector is, however, restructuring, and companies are merging in order to become bigger and more effective (Rao 2016; Schüler-Zhou et al. 2019). This consolidation process has been under way since many years, but the structure is still fragmented compared with the rest of the world.

Companies of the different groups have various motives for their choice of investment countries and behaviour. The private companies are driven by economic profits, while the Chinese state-owned companies in addition are influenced by overarching state priorities and politics. It seems, however, as if the state-owned companies are also gradually given more freedom (Jansson 2011 p. 6). Many Chinese companies, in particular the major ones with international listings, are in general the longer they have been exposed to the global markets, operating more like their international competitors when evaluating projects, acquisitions and in planning their strategies (Chintu and Williamson 2013; Alden and Davies 2006; Xu 2014).

The Chinese companies controlling mines operating abroad include a variety of entities from small-scale private operators; small- and mid-sized companies listed in Hong Kong or on a local Chinese stock exchange, without strong state interests; to companies, listed or not, under varying degree of state-control. This range of companies contradicts the idea of a “China Inc.” where activities of all Chinese entities abroad are coordinated from Beijing (Cissé and Anthony 2013; Southall and Melber 2009 p. xxi; Xu 2014). Certainly the influence from central state organs in Beijing is still considerable and should not be underestimated, but how this power over companies, state-owned or private, will develop into the future is not clear and will require continuous study.

Chinese control over African mine production

All Chinese mining investments into Sub-Saharan Africa between 2006 and 2017 are estimated at USD 33 billion, representing not more than 12% of the total Chinese investments in all economic sectors. The largest sectors are transport (infrastructure) and energy (Mudronova 2018).Footnote 15

By 2000, the Dilokong chromite operation was still the only operating mine controlled by Chinese interests in Africa. It accounted for 0.009% of the total global value of global mineral and metal production at the mine stage (see Table 4) where we have also included the Chinese-controlled share as a percentage of total value of African production of minerals and metals at the mine stage. This figure was, of course, a little higher than the global figure but still a miniscule 0.06% in 2000.

The level of Chinese control grew quickly in the early 2000s, albeit from a very low level, and was up to 0.4% of the total value of African production in 2005 and 0.054% of the total value of the world. In 2010, there were producing mines controlled by Chinese interest in four African countries Ghana, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The Chinese-controlled share of production from all these mines was less than 0.1% of the total world value or around 0.5% of the total value of all African production. In 2013, production had increased in some of the mines already operating in 2010, and new copper mines had been opened in DRC and in Zambia. Gold One had further acquired gold mines in South Africa, and Hebei Iron and Steel had taken control of the Palabora copper mine, and finally manganese production was running in Gabon. In total, Chinese control amounted to 0.25% of total world value or 2.2% of total African value.

Growth accelerated in five years between 2013 and 2018, and Chinese control was 0.8% of the total value and almost 6% of the total value of African mine production at the end of the period.

To put the African situation in perspective, we have also calculated the share of total global production controlled by Chinese entities in all countries (including Africa) outside of China.

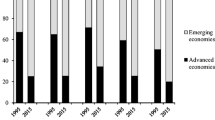

This curve has a similar shape as the one in Fig. 5 with a lag period over 15 years and an almost exponential growth during the past decade (see Fig. 6).

An analysis of the share of total value of mine production in each country controlled by Chinese companies gives an idea of the importance of the Chinese investments in individual countries. In 2018, Chinese companies controlled less than 12% of the total value of minerals and metals produced in Zambia. The figure in the DRC is 24%, roughly twice that in Zambia. The Chinese companies have been focusing on DRC not only because it has high-grade copper deposits, many of them well-known but abandoned during the many years of neglect by the state-owned Gecamines, but also because competition from other transnational companies has been reduced due to the country and reputational risks involved in operating in the DRC.

In Eritrea, where there are no other mining companies active, the Chinese companies share control with the Eritrean government (60/40). In Guinea, the Chinese companies control 37% of total national mine production. These figures are obviously higher than in Zambia and the DRC, although the total value of mining in Zambia and the DRC is much higher than in Guinea and Eritrea. Mining also means considerably less to the total economy of Eritrea and Guinea than it does in Zambia and the DRC (Ericsson and Löf 2019). In Gabon, 25% of the manganese production is controlled by CITIC, and as there is hardly any other mine production at present the Chinese company plays an important role on. In Congo (Brazzaville), Chinese-controlled Mfouati is the only industrial mine in operation; thus Chinese influence measured by the share of control over national production is also high. In other African countries, such as Ghana, Namibia and South Africa, production controlled by Chinese companies is limited in comparison with the total national mine production.

Copper, bauxite, cobalt, zinc, gold, manganese, chromite and uranium, in that order, are the economically most important metals controlled by Chinese companies in Africa (see Table 5). In the same table is also shown the share of Africa in China’s total overseas production of the same metals and the Chinese share of total African production.

Chinese companies have control over 28% of African copper production through their strong position primarily in the DRC but also in Zambia. The control over cobalt production by identified Chinese companies is higher at 41%. In order not to underestimate corporate control, we have not allotted any control to Gecamines in spite of its theoretical share of production from mines where it is a co-owner with companies such as China Moly, Glencore, First Quantum and Euroasian.

Control over African copper production in 2018 on a company by company basis is given in Fig. 7. It should be underlined that in spite of the quick growth during the past 10 years, Chinese control does not exceed 30%Footnote 16 of total African production. Other transnational companies (Glencore, Barrick and First Quantum) together control a larger share of copper production than the Chinese.

Chinese control over cobalt production in the DRC is of particular concern (Al Barazi 2018) given the large share of the DRC in total world production and the crucial role of cobalt in battery technologies for a global transition to a fossil-free future. Using our definition of control, at least partial ownership of a mine is a necessary requisite. In the case of DRC, there are however a large number of artisanal small-scale miners. Their production is sometimes bought by Chinese traders and small companies, and it could be argued that the real Chinese control is larger than what we calculate.

To get an idea of how large these amounts are, we have made the following analysis. Cobalt production in the DRC is reported to be 82 kt in 2017 (Reichl and Schatz 2019). The major non-Chinese companies have been Glencore and Euroasian. Glencore has reported production of 27 kt. Euroasian production has been reported at 10 kt, but according to a field study, it has declined and was only 3 kt in 2017; we have used the lower conservative figure (Al Barazi (2018) p. 79) . Two companies controlled by Indian interests account for 7 kt and including George Forrest Company a total of 11 kt. (see Table 6 for details).

Among the Chinese-controlled mines, Tenke Fungurume and Metorex have published their production of 19 kt for 2018 and 5 kt (2017) respectively. Using the total national production figure as a starting point small-scale production accounts for the balance or 20 kt (Al Barazi 2018; BGR 2019), of which Chinese Huayou is estimated to control around 12 kt. If we assume that all remaining small-scale production is controlled by Chinese companies, we will not be making an underestimate as there are known small-scale operations controlled by other companies. Total Chinese control could hence be maximum 41 kt, or 50% of the total production in the DRC.

Cobalt production in Africa outside the DRC (Madagascar, Morocco, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Zambia) is reported to be 10 kt. Chinese-controlled mines in Zambia could produce some small volumes of cobalt (3–4 kt), and in no other African countries is Chinese control over cobalt producing mines known to us. Chinese control over total African cobalt production would hence not exceed 50%. We believe that the possible underestimation of Chinese-controlled cobalt production in Zambia is balanced by the overestimation made in the DRC. There is still the risk of serious underreporting in the total national figures for the DRC, but we have no possibility to assess the likelihood of this.

The strong growth and high absolute value of Chinese-controlled bauxite production show that Chinese companies are expanding their focus and taking new opportunities when they emerge. Other metals play a less prominent role in the total picture of China in Africa. It is however worth noting that alloying metals such as chrome and vanadium from Africa account for 100% of Chinese total global control over production of these metals. Like cobalt, vanadium is a so-called battery metal, which could become crucial in the transformation to a fossil-free future. Projections of future demand for these metals are however particularly uncertain due to unknown future developments in battery technologies which today are not mature.

If the value of controlled mine production in Africa in 2018 is calculated on a company basis, the largest Chinese company by far is China Moly, which controls around USD 1.3 billion (1.5% of total value of African production). CNMC, in second place, controls some USD 440 million (0.5%) followed by Zijin and Minmetals each with around USD 400 million, and Jinchuan some USD 250 million.

The fast increase in bauxite production in Guinea has turned Hongqiao into a new major player. If this company is considered to have full control over the joint venture SMB, which we have, however, not been able confirm because the exact ownership figures and the internal agreements between the parties are not available, they would control a production value around one billion dollars and be ranked among the top Chinese companies in African mining.

Manganese prices have skyrocketed over the past few years, and the value of production from CITIC’s Bembele mine in Gabon could possibly also be reaching the same order of magnitude.Footnote 17 If the price of manganese stays at this high level, CITIC would become one of the largest Chinese mining companies in Africa.

Corporate control over total value of African mine production in 2018 is outlined in Fig. 8. Measured in this way, Anglo American alone controls more than twice the aggregated control by all Chinese companies and is around 10 times larger than the single largest Chinese company China Moly in 2018. This Chinese company is ranked as number 10 in Africa, controlling the same share of total African mine production as Harmony, Newmont and Gold Fields. This is so also after allowing for substantial Chinese control of small-scale producers of cobalt.

The Chinese stepwise investment into Ivanhoe Mines could possibly make it the first listed major mining company controlled by Chinese investors. Started and operated by mining mogul Robert Friedland, Ivanhoe has discovered Kamoa-Kakula, a copper deposit in the DRC with very high copper grades, on average 5.5% Cu. It is the most important new deposit identified in DRC in the past 50 years. As a comparison, grades at competing large copper mines around the world hover at, or below, 1%. Zijin bought 50% of the project for USD 412 million in December 2015 when copper prices were plummeting. The Chinese company is also one of the largest shareholders in Ivanhoe at 13.8%, acquired in steps since March 2015.

Together with CITIC which has an equity stake of 26.4%, the Chinese interests account for just above 40% of Ivanhoe. The Kamoa-Kakula mine could possibly already in 2021 become one of the world’s largest copper mines. Ivanhoe also runs the Kipushi zinc project, yet another copper project in the DRC and a platinum project in South Africa. Clearly successes in any or all of these projects will increase Chinese control over African mining in one single leap.

Our analysis of Chinese investments into African and global mining has revealed a couple of trends and characteristics. At least in the initial phases of overseas expansion, Chinese companies have overpaid for difficult and marginal assets. Chinese investments in Australia and Canada have met with strong political opposition, particularly when major companies were involved. Deals have often been made with government entities in the host countries. The projects in which the Chinese investors have relied on local management seem more successful than when Chinese management has been installed.

Gradually, however, Chinese companies are learning by their mistakes. The Chinese companies are getting more effective and knowledgeable, and some of them will most probably in the next decade compete successfully with their global peers. When Chinese-controlled operations are sold, they are often taken over by other Chinese companies. Chinese-controlled mine production is mostly exported as raw ores or concentrates and not beneficiated in the host countries. It remains to be seen if recent proposed investments into alumina production in Guinea and Indonesia will materialise and change this situation.

Future developments

The future level of Chinese control over mineral and metal production outside China, whether in Africa or globally, depends on a number of overarching economic and political factors such as: How will metal demand in China develop? Will Chinese government continue to push for improved security of supply? Will mineral-rich host countries in Africa and around the world become more critical to Chinese investments? The behaviour of Chinese companies on the ground will also be important: How successful will their overseas projects be?

There are two main ways of taking control over mineral production: by acquiring an existing mine or to start exploration to find a deposit. The first route is instantaneous, while the second alternative takes years and is often highly risky in that even large amounts spent do not guarantee success. Geologists and mining engineers mention a success rate of perhaps one mine out of 100–1000 exploration projects. The success rate increases and the lag time decreases for projects where a deposit has already been identified. In countries where mining is an established industry, financing, permitting, engineering and construction are further often quicker than in countries without a mining history.

Chinese and global metal demand will most likely continue to increase in the next 5–10 years, but probably at a slower pace than in the 2010s. Demographics and global economic development point in this direction. The present push towards a fossil-free future will further support this growth. China may not play as important a role in increasing metal demand as during the Super Cycle but will no doubt still be a dominating driver.

With a growing import dependency, the Chinese government will probably want to improve supply security—as has been the policy for long. This can be done by increasing domestic production, but there seems to be increasing obstacles to such expansion. In the provinces around Beijing, as much as 30% of China’s alumina capacity could be shut down to combat pollution (Farooki 2018, p. 2). An “environmental paradigm shift” is said to be underway in China and the so-called Green Mining Development initiative is but one part of this shift (Dolega and Schüler 2018).

The other way to increase security of supply is to increase control by Chinese companies over overseas mining operations. In addition to the security of supply issues, there is, and has been, a strong Chinese worry about the monopoly powers of the major transnational mining companies. Even if it can be discussed how well-founded this worry is, it has most probably been one important consideration when investing at least in some of the iron ore mining projects, including the ones which have failed.

More stringent environmental regulations and energy limitations are being introduced in China. Together with an increasing general cost situation, this will reduce profits in many domestic, small by international standards, Chinese mines and make overseas projects more attractive. On a general political level, new mines controlled by Chinese companies will increase security of supply compared with imports from the world market even on long-term contracts.

To maintain its share of control over mineral production, Chinese companies must continue to invest, and if the share of controlled production shall increase, investments must be higher and more successful than for investors from the rest of the world. We have not measured the global investments into mining in relation to the Chinese ones in recent years but can only draw our conclusions from the projects Chinese investors are involved in at present, globally and in Africa.

At a global level, Chinese recent investments in major world class projects, and an increased appetite for the new “green” metals, such as lithium, indicate that there is continued willingness in Chinese companies for acquisition of new capacity. This is a less risky way forward. Present Chinese politics seems to support this trend to increase security of supply, or at least not increase dependence on the major transnational mining companies. Recent news confirm this: Jiangxi Copper becoming the largest shareholder in Canadian First Quantum, which is the major shareholder in the Kansanshi copper mine in Zambia (Lewis 2019), and Zijin taking over Continental Gold, a Canadian junior running the Buritica gold project in Colombia with production planned to start in late 2020 (Zijin, Continental Gold 2019).

For Africa, we will try to deepen the discussion, and will start with a review of projects under way, first exploration efforts and later all type of projects.

Chinese exploration expenditure in Africa is one long-term indicator of the likelihood of increased control by Chinese companies over African mineral production. If many exploration projects are running, the probability that new deposits will be found is higher.

In an annual survey (Metals Economics Group 2012) of global exploration activities, the first two Chinese companies active in Africa were mentioned in 2010: Zhonghui and China Nonferrous spending together USD 18 million in Zambia in search for mainly copper. This was equal to 17% of total exploration investment in Zambia that year. In 2014, exploration efforts had been stepped up in Zambia, with three Chinese companies, Jinchuan, China Nonferrous and MMG, spending USD 25 million, around 21% of the total in Zambia. In the DRC, Jinchuan and MMG invested USD 31 million. In all, including also unreported amounts, by companies not surveyed, we estimate that more than USD 60 million was invested in exploration by Chinese companies in Africa in 2014.

Out of the total exploration investments in all of Africa (USD 1.7 billion) in 2014, however, Chinese companies contributed less than 3%. The amount shows the limited size of Chinese exploration efforts historically and today. There are no indications that the Chinese exploration efforts have been increasing dramatically in the past years. Possibly the effectiveness has increased, with Chinese companies having 10 years of experiences under their belt. The quick growth in bauxite production in Guinea could indicate that Chinese companies might be able to deliver also green field projects on their own. But even that will most probably not be sufficient to turn the limited exploration expenditure into a string of new projects potentially increasing Chinese control.

The number of Chinese projects underway in Africa in any year during the past 25 years is another indicator of potential future Chinese production. From Table 1, one version of this indicator can be calculated. This gives, however, an underestimate as this table only includes projects, which have been turned into mines during the period under study. This shortcoming is partially remedied by including projects from Table 2 (see Table 7).

In 1995, there were no projects or operating mines in Africa; in 2013, the number of operating mines was 15 and the projects underway had increased to 16. There has been a decline in projects running in 2018, but the number of mines has continued to increase. This is partly due to that some projects have been turned into mines. There is, however, also a risk that we might have missed some projects, and it is too early to draw any definitive conclusions from this decline. Given that the time lag for an exploration project to be developed into a mine is often up to 15 years, it thus seems that there is some potential for the Chinese control over African mining to increase in this way in the future.

Yet, another indicator of potential future growth is the total number of exploration and other early stage projects globally and in Africa as reported in Raw Materials Data at the time. There were 175 such Chinese-controlled projects listed in 2013, of which a majority were in Australia, roughly half of the total, but Africa was the continent with the second highest number, some 30 projects, indicating potentially increasing number of mines in the future. A similar count of projects was made in 2017 arriving at a figure of around 240 projects (Farooki 2018, p 9).

These numbers of projects alone are not likely sufficient to underpin continued Chinese growth of mine production and control in Africa in the next 5–10 years. With a limited number of exploration projects running, it seems as if the bulk of Chinese additional mine production, and hence increased control over African mining, during the next 5–10 years will have to come from expansion in acquisitions already made or from those to come. The development underway in Guinean bauxite and Congolese copper/cobalt are perhaps the most obvious examples. Further, a gradual entry into east Africa would be possible with Eritrea as the base.

There are factors supporting a continued growth of Chinese control of African mine production, while others are working in the opposite direction. These factors are working inside China and in the world. We start with the factors facilitating expansion by Chinese companies.

These companies have gained experiences and have overcome some of the problems encountered in the early days. This means that with the same amount of capital invested more effectively Chinese companies are more likely to increase their production and hence control. In the early 1990s, only a limited number of Chinese companies had been operating in Africa; mostly companies engaged in previous development aid projects such as the Tazara railway and others. As we have already pointed out, Chinese companies in general lack suitable technical skills to operate large-scale, highly productive mines, let alone in foreign countries with different political, cultural and weather conditions, and on top of this, in an unfamiliar business climate. This was true also for the Chinese construction companies generally contracted to build the mines, the processing plants and the necessary infrastructure in the Chinese-controlled projects. The initial, largely unfounded optimism, both in China and in Africa, has been replaced by more realistic expectations and judgements of all type of risks involved in any mining project.

Chinese investment capital will most likely not be flowing as freely in the future as it once did and this might hamper overseas expansion by Chinese companies. The failed or postponed projects, such as the iron ore mines Bong, Simandou and Tonkolili, have further made both the mining companies and in particular the banks and other financial institutions, backing the Chinese expansion into Africa, more careful and less risk-willing. There are also indications of a more restrained Chinese policy in general concerning FDI (Anonymous 2019). Lately increasing flows of minerals and metals from Latin America have become an alternative to Africa. These imports are often sourced from countries carrying less political risks and offering a higher level of mining maturity and political stability at least compared with some of the African countries.

In the next decade, the competition for African projects may become tougher than it has been in the past. One explanation behind the Chinese growth in Africa during the past 20 years is that the transnational companies with roots in Europe, North America and South Africa, traditionally dominating African mining partly withdrew from Africa. They wanted to spread their risks geographically. By 2020, this process has been concluded, and their portfolios are well-balanced as far as geographical risks are concerned. The transnational companies could from now on become interested once again in investing in Africa for the same reasons as their Chinese competitors. The Chinese successes so far will certainly further increase the interest of the major transnational companies to invest in Africa. In addition companies from emerging economies such as India, Brazil, Russia and others have also been active and are competing for Africa's resources (Melber 2010).

In some countries, for example Zambia, there have been an active political opposition to the Chinese presence in general and some of the practices of the Chinese companies (Hairong and Sautman 2013). This might affect the willingness of Chinese companies to continue investing in mining in Zambia and possibly in other countries.

In summary, the increasing number of overseas projects and the improved ability of Chinese companies to turn these projects into operating mines indicate continued expansion by Chinese companies globally and in Africa. At the same time, there are divergent political signals in China, on the one hand more stringent environmental regulations and calls for supply security and on the other a more careful FDI policy. The vast untapped mineral potential in Africa will remain the key driver for continued activities by Chinese companies. It seems likely that Chinese overseas mining investments and hence Chinese control over global mining production will continue to increase also into the future, albeit most probably at a slower pace than during the past five years.

Discussion

Ownership of mines is used as a measure of Chinese control over global and African mining. As pointed out, this is partly a simplification as there are other ways to exercise control. What would Chinese control be if these additional control mechanisms could be included?

Management

Management as discussed Chinese companies had limited management practices and experiences rather the opposite; they went on a steep, but nevertheless a learning curve.

Interlocking directorates

Interlocking directorates exist in some companies such as Teck, the Canadian base metals producer, and some of the big Australian iron ore JVs, as well as in Fortescue but are absent in other companies with Chinese minority owners such as Sibanye, the South African gold and PGM producer.

Technology

Chinese technologies have, in general, not been of such standards that they could have been used to increase Chinese control over mine production.

Long-term contracts

Some of the Australian iron ore mines and JVs have long-term contracts with their Chinese owners, and customers, for example Hunan Valin’s 14% in Fortescue are strengthened by long-term contracts.

Infrastructure

For bulk minerals, in particular iron ore and bauxite but also copper, control over the transport routes are crucial, without a railroad and a port no export and no project. This situation has made the resources for infrastructure (R4I) swaps a key factor in Chinese investments into Africa. R4I swaps have been employed in the DRC and Angola to transport copper out of Central Africa and a model to secure access to mineral resources for China (Alves 2013; Konijn 2014). An earlier example is the Tazara railway from Zambia to Indian Ocean. To get iron ore projects in Gabon, Guinea and Sierra Leone going the infrastructure is a crucial component, which has not yet been solved, and hence, only limited mining has started. It is not obvious how the Chinese investments into the transport sector has affected its control over African or global mineral production, nor are they simple to evaluate and quantify. Often, these infrastructure projects connect Chinese-owned projects to export markets and hence do not add much control to what is already exercised through ownership.

The Chinese control through ownership of cobalt production in the DRC is amplified by vertical integration and further downstream processing of cobalt ores and concentrates in China. This additional control is difficult to differentiate from the power stemming out of the market knowledge it is closely associated with. Together, these two factors strengthen the ownership control Chinese companies exert over the cobalt industries. In lithium, a similar situation could possibly develop in the future. Both these factors, vertical integration and market knowledge, partly stem out of the growing presence of Chinese trading companies (Löf and Ericsson 2019).

The most important additional ways to control mine production used by Chinese companies and government are financial and political support to countries in particular in Africa. Between 2000 and 1018, Chinese loans to African governments and state-owned enterprises amounted to 152 billion USD. Angola has received the bulk of these loans almost 30%. Ethiopia, Kenya and Sudan together account for another 20% of total borrowing in the period up 2017. Two mineral-rich countries are Zambia and the DRC which have received almost 14 billion (9%) in loans. Until 2017, loans to resource extraction were 19.4 billion of which 91% went to Angolan state-owned oil company Sonangol, the rest to the Sicomines JV in the DRC, one of the Eritrean goldmines and probably two uranium projects in Namibia and Niger, in all relatively minor amounts. The original 9 billion to DRC was renegotiated and reduced to 6 billion, and only 1.3 billion has actually been disbursed. The amounts loaned were increasing until 2013 and has since then gradually gone down except for a peak in 2016 (Hwang et al. 2016; Brautigam 2020, CARI data 2020).

These two control mechanisms are difficult to measure and quantify. Without the financial support given to Chinese companies, their expansion would most probably have been slower than it has been. The policy background to and implications of Chinese aid and geopolitical ambitions have been the focus of a range of studies for a review (see Konijn 2014). There are no direct links between Chinese aid and loan policies and host country policies unlike the practices of the IMF and the World Bank and other donors. Case studies of the implications of R4I swaps in Angola, the DRC, Gabon, Ghana and Nigeria showed that such swaps “do not inherently exacerbate the resources curse nor are they a panacea for its ills” (Konijn 2014 p.3). The Belt & Road Initiative might become a new Chinese programme that could strengthen its control over mineral production but so far there are limited signs of that this is happening (Farooki 2018).

Some of the indirect ways of controlling mine production are employed by Chinese companies and government, others are not. But in particular, the financial support given to Chinese companies and the building of transport infrastructure to ship metals and minerals are important ways of increasing Chinese control. Chinese control over global and African mine production could hence be higher than what the ownership share indicates, but it is not possible to quantify their importance. We have not found clear evidence supporting the hypothesis that these additional control methods would increase Chinese control substantially in comparison with its ownership shares.

Chinese investments in African mining have contributed to the growth of African mine production. An important hypothetical question is, for African host governments and metal consumers around the world: if other investors would have stepped in had the Chinese not been as active as they have been? Be that as it may, we can only note that as a result of the Chinese investments Africa has been among those regions of the world where mine production has grown and where mining has made the largest contribution to national economies.

Part of the explanation for the attractiveness of Chinese investors to African host countries is simply that they have been prepared to invest, and they have also offered relatively favourable conditions, at least on paper. At the same time, it is clear that the Chinese companies have had the same basis for their investments as the traditional major mining companies: to extract minerals and export as much as possible as fast as possible and with a profit.

The overseas mining activities of Chinese companies have affected global metal markets, host countries and competing mining companies. But, equally importantly, the Chinese companies are gradually also changing their behaviour reacting to pressures from the markets. An Australian study asked the question: “Are there particular problems associated with investments from foreign state-owned enterprises or state-managed sovereign wealth funds?” The answer was “Nor does the participation of the Chinese sovereign wealth funds... present any particular problems that cannot be dealt with appropriately within the policy framework that has been in place for some time” (Drysdale and Findlay 2009).

Another important follow-up question is: What effects have the Chinese push into global minerals and metals market had? As one long-time researcher of the global mining industry has put it: “Do Chinese equity acquisitions, loans, and long-term procurement contracts help consolidate a tightly concentrated supply base by securing preferential access for Chinese buyers, or do they help multiply sources and diversify the supply base, making the provision of output more competitive for all buyers?” Based on 21 cases from oil and minerals made in 2010, the study concluded: “the empirical record to date suggests a predominant thrust ... towards diversification of output and enhanced competition among producers” (Moran 2010). It would certainly be interesting to see a follow-up study.