Abstract

Introduction

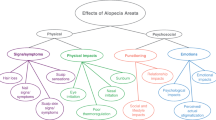

The physical impact of alopecia areata (AA) is visible, but the psychological and social consequences and emotional burden are often underrecognized.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 547 participants recruited via the National Alopecia Areata Foundation completed a survey encompassing demographics; AA illness characteristics; and five patient-reported outcome measures on anxiety and depression, perceived stress, psychological illness impact, stigma, and quality of life (QoL). Differences in disease severity subgroups were assessed via analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t tests.

Results

Mean age was 44.6 years, and 76.6% were female. Participants with more severe hair loss tended to report longer duration of experiencing AA symptoms (P < 0.001). Overall, participants reported negative psychological impact, emotional burden, and poor QoL due to AA. Participants with 21–49% or 50–94% scalp hair loss reported greater psychological impact and poorer QoL than those with 95–100% scalp hair loss (most parameters P < 0.05). Similar results were observed for eyebrow/eyelash involvement subgroups.

Conclusions

These results suggest that participants with AA experience emotional burden, negative self-perception, and stigma, but the impact of AA is not dependent solely on the amount of hair loss. Lower impact among participants with 95–100% scalp hair loss may indicate that they have adapted to living with AA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

While the physical impact of alopecia areata (AA) is usually visible, the psychological and social consequences on work or daily life, and emotional burden are often underrecognized. |

Hence, this study’s aim was to delineate the emotional burden of AA and to examine whether the emotional burden of AA was differentiated based on the degree of scalp hair loss or involvement of eyebrow/eyelash loss. |

What was learned from this study? |

This study demonstrates that the emotional burden of AA goes beyond anxiety and depressive symptoms to impact perceptions of self and feelings of stigma. |

Also, the impact of AA on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is not solely driven by the amount of scalp hair loss and suggests that inclusion of psychosocial impact is warranted in consideration of disease severity and patient management. |

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a clinically heterogeneous, autoimmune, nonscarring hair loss disorder that varies widely in the amount and pattern of hair loss [1]. While the physical impact of AA is usually visible, the psychological and social consequences on work or daily life, and emotional burden are often underappreciated. Hair loss may be perceived as a cosmetic problem by others, but for patients with AA, the shame, guilt, and loss of self-confidence associated with hair loss can lead to emotional distress and diminished quality of life (QoL) [2, 3].

In a survey through the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF) of 216 respondents, 85% stated that coping with AA was a daily challenge, and cited mental health issues, with 47% reporting anxiety and/or depression [4]. In a systematic review of the literature across > 70 studies, the rates of emotional symptoms and comorbid psychiatric disorders were consistently elevated in patients with AA compared with patients without AA [5]. Due to limited options for long-term effective therapies, many patients with moderate to severe AA either learn to tolerate their loss of hair, or try restorative interventions such as cranial prosthetics, camouflage, and cosmetics. These restorative interventions are often uncomfortable, and patients may fear having to involuntarily disclose their illness due to the elements or certain activities [2, 3].

In another survey of 1327 participants, the impact of AA upon health-related QoL was measured using the Skindex-16 AA, which assesses the domains of emotional/subjective, relationships, and objective signs. Respondents were stratified by severity of scalp hair loss or eyebrow and eyelash involvement. Not only did respondents report the negative impact of AA on their emotions and relationships, but there was a nonlinear relationship between severity of scalp hair loss and degree of emotional distress and QoL impact. Participants with 21–49% or 50–94% scalp hair loss had a greater impact on their lives compared with those with 95–100% scalp hair loss [6].

While these previous studies have provided insights into the emotional and psychosocial toll of AA, the objective of the present study was to extend this research by including psychosocial measures that were specifically designed to assess the perceptions of stress, stigma, and the impact of being diagnosed with an illness. In addition, the present study examined whether the emotional burden of AA was differentiated based on the degree of scalp hair loss or involvement of eyebrow/eyelash loss.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

This cross-sectional, noninterventional, web-based survey was conducted from May to June 2021. Participants were recruited through the NAAF, which primarily has members from the USA but also includes international members. Inclusion criteria for the study included adult (≥ 18 years old) age; a self-reported, physician-rendered AA diagnosis; current scalp hair loss; and consent. Participants were also required to read and understand English. Recruitment was allocated to ensure that the full range of scalp hair loss severity was represented among the subjects. Once the proportion of participants within a category had been met, further participants reporting that amount of hair loss were ineligible. Participants were reimbursed a nominal amount and were allowed to complete the survey only once.

Recruitment Methods

NAAF recruited participants with AA by sending out recruitment e-mails to their membership database and posting advertisements on their social media accounts. AA participants who were interested in the study were able to access the screener, electronic informed consent form (eICF), and subsequent survey using the link included in the recruitment e-mail or advertisement. YouGov, a third-party recruitment vendor specializing in health outcomes market research, programmed and hosted the web-based survey. The survey restricted participants from being able to complete the survey multiple times by having internet protocol (IP) addresses blocked after the first attempt.

Measures

The survey comprised 83 questions encompassing demographics, baseline illness characteristics, and five patient-reported outcomes (PROs) on the emotional and psychosocial impact of AA. Questions describing current disease status included the PRO for Scalp Hair Assessment™, PRO Measure of Eyebrow™, and the PRO Measure for Eyelash™. Patients self-reported the severity of their scalp hair loss, eyebrow loss, and eyelash loss as one of the categories shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 [7]. Emotional impact and QoL were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Toolbox Perceived Stress Fixed Form Age 18, Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Psychological Illness Impact—Negative 8-items, PROMIS Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-QoL) Stigma 8-item, and the Alopecia Areata Quality of Life Index Questionnaire (AA-QLI).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The HADS is a 14-item measure designed to assess anxiety and depression (seven questions each) in the past week [8]. Each question on the numeric rating scale (NRS) has four response options ranging from “not at all” to “very often indeed.” The response options for each question may differ but have similar meaning. Scores are calculated separately for anxiety and depressive symptoms and range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater distress. HADS anxiety scores or HADS depression scores of ≥ 8 are considered borderline/abnormal [8].

NIH Toolbox Perceived Stress Fixed Form Age 18

The NIH Toolbox Perceived Stress Fixed Form Age 18 is a ten-item questionnaire designed to measure the perception of stress over the past month in adults [9]. Participants responded to each item on an NRS scale of 1 (“never”) to 5 (“very often”). Total scores are converted to a T-score, with higher scores indicating stress severity relative to a general population mean of 50. Thus, a T-score of 60 is one standard deviation (SD) worse than average, while a perceived stress T-score of 40 is one SD better than average.

PROMIS Psychological Illness Impact—Negative 8-Item

The PROMIS Psychological Illness Impact—Negative 8-Item assesses the negative impact of a given illness, using two different recall periods (“before your illness” and “since your illness”) to capture the perceived change in impact [10]. Item content includes impact on self-worth and self-perception, feelings of isolation, worry about future, and life/health interference. Participants responded to each item on an NRS scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”). As with other PROMIS measures, the total score is the sum of the individual items, which is then converted into a T-score. With the general population mean score of 50, a T-score of 60 would indicate a greater psychosocial impact.

PROMIS NeuroQoL Stigma 8-Item

The PROMIS NeuroQoL Stigma 8-Item assesses patient-perceived stigma caused by the illness in the last 7 days on an NRS scale of 0 (“never”) to 5 (“always”) [11]. Summation of the individual items gives the total score ranging from 8 to 40, which is then converted into a T-score. Higher stigma T-scores indicate greater perceived stigma relative to the general population. A T-score of 60 is one SD worse than average, and a stigma T-score of 40 is one SD better than average.

Alopecia Areata Quality of Life Index Questionnaire

The AA-QLI comprises 21 questions assessing the degree to which a patient has been affected by AA within the last month in three main areas of daily life: subjective symptoms, impacts on relationships, and objective signs [12]. Each question on the NRS scale is scored from 1 (“not affected at all”) to 4 (“highly affected”). Summation of individual items in each domain provided each domain’s scores. The subjective symptoms and relationships domain scores ranged from 9 to 36; objective signs domain scores ranged from 3 to 12. The total AA-QLI score was calculated using this formula:

The total AA-QLI score ranged from 0 to 100, where higher scores refer to worse health-related QoL.

Statistical Analysis

For each measure, descriptive analyses were conducted using either mean/SD for continuous variables and counts/proportions for categorical outcomes. Comparisons across measures were done for subgroups: (1) amount of scalp hair loss (limited/moderate/large/nearly all), and (2) involvement of eyebrow or eyelash loss (full eyebrow/eyelash, minimal gaps/minimal thinning, large gaps/large amount of thinning, and no or barely any eyebrow/eyelash). Significant overall subgroup differences were assessed using ANOVA with follow-up t-test between specific subgroups. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All statistical tests used a two-sided significance level of 0.05, unless otherwise noted. Subgroup analysis by gender, race, current signs and symptoms, treatment satisfaction, and HADS anxiety and depression domains was performed to compare variables such as HRQoL and psychosocial impact.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Patients provided written, informed consent for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals. No personal identifiable information was collected, and all responses were anonymized. The study was reviewed and approved by Advarra Institutional Review Board and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

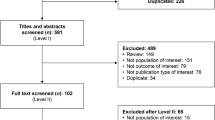

Among 2183 individuals who clicked on the survey link, 1040 were screened out due to ineligibility or the predetermined recruitment targets. Among 1143 eligible participants, 547 completed the survey. The primary reason for ineligibility was related to the prespecification, as patients had to be recruited from each category of scalp hair loss (limited, moderate, a large area, and nearly all or all) to obtain representation across the spectrum. The mean (SD) age of the participants was 44.6 (14.8) years, and most of them were female (76.6%), white (68.6%), and full-time employees (60.0%) (Table 1).

Table 2 describes the participants’ clinical characteristics. The average duration of AA was 18.0 (14.7) years, with the majority (67.5%) reporting a current episode lasting for > 4 years. AA universalis (42.8%) and AA multilocularis/patchy (30.7%) were the most common current hair loss patterns, with 64.6% having ≥ 50% scalp hair loss. Similarly, 49.4% and 40.6% of the participants reported having “no or barely any” eyebrows and eyelashes, respectively. Approximately a third stated that they were not currently seeing a healthcare provider for their AA.

Among the participants, 27.5% rated themselves as “very dissatisfied” with their current therapy. Interestingly, 28.9% of the participants were not receiving any treatment (Table 3).

Severity of scalp hair loss was significantly associated with a few demographic and clinical characteristics (Supplementary Table S2). Specifically, participants with more severe scalp hair loss tended to report a longer duration of experiencing AA symptoms, with a greater proportion experiencing their current hair loss episode for > 4 years (all P < 0.001).

Emotional and Health-Related Impact of AA—Overall Participants

Table 4 describes the PRO instruments’ scores. For HADS, respondents overall reported higher mean [SD] anxiety scores (9.0 [4.5]) than depressive distress (5.8 [4.2]). Most respondents were in the “abnormal” (37.5%) or “borderline abnormal” (24.3%) categories of the anxiety domain, and in the “normal” (66.4%) category of the depression domain. Respondents also reported slight elevations in their perceived stress compared with the general population, with a mean NIH Toolbox Perceived Stress score of 58.2 (9.9). Although respondents’ perceptions of themselves and their futures were similar to the general population before developing AA (mean [SD] PROMIS Psychosocial Illness Impact score 49.7 [9.1]), they experienced increased psychosocial disruption following disease onset (59.6 [11.6]). The highest mean (SD) item scores after AA diagnosis were reported for “I worry about the future” (3.3 [1.3]) and “Worry about my health interferes with my life” (3.2 [1.4]). Respondents also perceived themselves as generally more stigmatized than the general population with a mean NeuroQoL Stigma score of 56.0 (8.5). The highest rated stigma item was embarrassment (mean [SD] score 3.6 [1.5]).

Beyond the emotional aspects of their illness, respondents also reported their AA had a significant impact on their QoL. The mean (SD) AA-QLI total score was 30.3 (7.9), showing a moderate impact of AA on QoL. Participants reported greater impact of their AA on the emotional/subjective symptoms and relationship domains than on the objective signs, with domain mean (SD) scores of 25.8 (6.2), 21.6 (7.3), and 8.3 (2.3), respectively (Table 4). Females reported higher scores than males on the AA-QLI total (31.2 versus 27.5) and domain scores i.e., relationships, subjective and objective symptoms (all P < 0.05) of the psychosocial illness impact form (Fig. 1). On the AA-QLI, respondents indicated the highest agreement with the phrases “I worry about having this hair problem for the rest of my life” and “I cannot forget that I have this hair problem” for subjective symptoms, “my scalp is visible” for objective signs, and “I think that other people notice my hair/eyebrows/eyelashes problem” for relationships (Supplementary Table S3).

Emotional and Health-Related Impact of AA—Severity of Scalp Hair Loss

On comparing the mean outcomes across the subgroups based on the amount of scalp hair loss, eyebrow, or eyelash loss, a non-linear relationship, expressed as an “inverse U shaped” curve, was observed. Participants with large (50–94%) areas of scalp hair loss reported significantly greater psychosocial impact (P < 0.05) than those with 95–100% scalp hair loss. Additionally, 50–94% scalp hair loss was associated with poorer QoL as measured by the AA-QLI domains for total score, subjective symptoms, and objective symptoms (P < 0.05 for all). Participants with moderate (21–49%) scalp hair loss also reported significantly poorer QoL than participants with 95–100% scalp hair loss, but only for the subjective and objective symptoms domains of the AA-QLI (P < 0.01 for both) (Fig. 2A). This suggests that a moderate amount of scalp hair loss may be as impactful as more extensive hair loss.

Psychosocial impact of AA by disease severity and location: A by severity of current scalp hair loss, B by severity of current eyebrow hair loss, and C by severity of current eyelash hair loss. Pairwise comparisons were performed for each subgroup, but P values for only moderate area scalp hair loss versus nearly all or all scalp hair loss, large area scalp hair loss versus nearly all or all scalp hair loss, minimal gap(s) or a minimal amount of thinning in at least one of my eyebrows versus no or barely any eyebrow hairs, large gap(s) or a large amount of thinning in at least one of my eyebrows versus no or barely any eyebrow hairs, minimal gap or minimal gaps along the eyelids versus no or barely any eyelash hair, and large gap or large gaps along the eyelids versus no or barely any eyelash hair are represented. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. AA-QLI Alopecia Areata Quality of Life Index Questionnaire, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, LS Least Squares, NIH National Institutes of Health, PROMIS Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System, QoL quality of life, SE standard error

Emotional and Health-Related Impact of AA—Severity of Eyebrow/Eyelash Involvement

Participants with large gaps or thinning in at least one eyebrow reported significantly greater anxiety and depression as well as significantly poorer QoL (P < 0.05 for all) than participants with total eyebrow loss (Fig. 2B). Participants with minimal gaps or thinning in at least one eyebrow only reported significantly greater anxiety and psychosocial illness impact (P < 0.05 for both), and poorer QoL in terms of subjective and objective symptoms (P < 0.01 for both) than patients with total eyebrow loss.

Participants with large gaps along the eyelids only reported significantly poorer scores in the objective symptoms AA-QLI domain (P < 0.01), while those with minimal gaps reported significantly poorer scores in both subjective and objective symptoms domains (P < 0.05 for both) than participants with total eyelash loss (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

These findings provide further insights into the emotional and QoL impact of AA. In the overall population, respondents reported significant anxiety, elevated stress, and substantial negative impact on their self-perception and health following the onset of AA. Subgroup analysis revealed a greater impact on participants with moderate and large areas of hair loss compared with participants with nearly all or complete hair loss. Females reported greater impact on the different domains of the AA-QLI compared with males, while both groups had similar emotional distress and stigma. The acute onset of AA, disease duration, extent of hair loss, and prognosis are all unpredictable. This unpredictability can result in ongoing anxiety among respondents about the status of their hair, independent of the actual severity of hair loss or response to treatment. Supporting this hypothesis, the mean level of anxiety and stress did not always differ significantly across subgroups, suggesting that even limited or moderate AA may result in substantial emotional impact. With respect to stigma, a linear relationship between amount of hair loss and perceived stigma was observed, with patients reporting greater perceived stigma in accordance with larger amounts of scalp hair loss.

The present findings also reinforce the impact of AA on QoL. In the previous NAAF survey [6], patients completed the Skindex-16 AA, which was adapted from the Skindex-16 for dermatological disease, with the replacement of “skin disease” with “hair loss.” Among the three domains of the Skindex-16 AA, respondents scored highest on the emotional and functional domains and lowest on the symptom domain, which consists of items regarding itching, burning, and pain. When examined by categorical subgroups based on amount of scalp loss, a non-linear relationship, expressed as an “inverse U-shaped” curve, was observed, wherein respondents with a moderate or large amount of scalp hair loss were as impaired as those with almost complete hair loss and those with a limited amount of loss had the lowest impact. Similarly, although the present study used a different measure of QoL, the findings were replicated, with respondents indicating greater impact of AA on subjective (emotional) and relationship domains and less impact from objective signs and symptoms.

Further, the non-linear relationship between severity subgroups and the emotional and functional impact of AA indicates that the relationship between scalp hair loss or amount of eyebrow/eyelash involvement and severity of AA as a disease is complex. In a recent study examining predictors of QoL, Senna et al. [13] found that the patient’s own perception of disease severity and the involvement of eyebrow/eyelash loss were the strongest predictors of diminished QoL, rather than physician-rated Severity of Alopecia Tool score. Altogether, these studies suggest that the emotional impact of AA and its corresponding impact on the daily lives of patients are somewhat independent of amount of scalp hair loss. It may be hypothesized that the differences observed between scalp hair loss-based subgroups of the current study are associated with a third factor, such as duration of disease. As participants with the greatest severity of scalp hair loss also had the longer duration of illness (mean 22.7 years), the lower emotional and psychological impact scores relative to the other subgroups may reflect a process of accommodation over time.

While traditionally the severity of AA has been defined by the amount of scalp hair loss, recent consensus work also recognizes that disease severity is influenced by other, multidimensional factors. Key additional factors include significant psychosocial impact on the patient, eyebrow and eyelash involvement, response to therapy, and progressive nature of the disease, including duration. In these recommendations, the conclusion is that the severity of AA as a disease should not be assessed unidimensionally, but rather should be evaluated holistically [14, 15]. Thus, as indicated by the findings of the current study, inclusion of the patient’s perspective and its emotional and psychosocial impact are essential to understanding overall disease severity and its appropriate management.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Most participants were female and/or white, which may influence the outcome relative to male patients or other populations. Since participants self-reported their clinical and disease characteristics, the accuracy of reporting illness characteristics may not correspond to clinician-rated outcomes. Recruitment via one patient advocacy group and its restriction to English may also limit the generalizability of these results to the general US population. Additionally, 64.5% of the participants reported having severe AA (≥ 50% scalp hair loss), which may have skewed the results toward higher psychosocial impact. Finally, the analyses were descriptive in nature and therefore no adjustments for key covariates were made.

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the experiences of patients with AA in the USA. It demonstrates that the emotional burden of AA goes beyond anxiety and depressive symptoms to impact perceptions of self and feelings of stigma. The impact of AA on HRQoL is not solely driven by the amount of scalp hair loss and suggests that inclusion of psychosocial impact is warranted in consideration of disease severity and patient management.

References

Islam N, Leung PS, Huntley AC, Gershwin ME. The autoimmune basis of alopecia areata: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(2):81–9.

Davey L, Clarke V, Jenkinson E. Living with alopecia areata: an online qualitative survey study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(6):1377–89.

Aldhouse NVJ, Kitchen H, Knight S, Macey J, Nunes FP, Dutronc Y, et al. “‘You lose your hair, what’s the big deal?’ I was so embarrassed, I was so self-conscious, I was so depressed:” a qualitative interview study to understand the psychosocial burden of alopecia areata. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):76.

Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, Ko J, Cassella J. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20(1):S62–8.

Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, Agbai ON, Kiuru M. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):162–75.

Gelhorn HL, Cutts K, Edson-Heredia E, Wright P, Delozier A, Shapiro J, et al. The relationship between patient-reported severity of hair loss and health-related quality of life and treatment patterns among patients with alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(4):989–97.

Wyrwich KW, Kitchen H, Knight S, Aldhouse NVJ, Macey J, Nunes FP, et al. Development of clinician-reported outcome (ClinRO) and patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures for eyebrow, eyelash and nail assessment in alopecia areata. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(5):725–32.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

HealthMeasures. NIH toolbox perceived stress fixed form age 18+ v2.0: HealthMeasures; 2021 [Available from: https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=683&Itemid=992. Accessed 10 Mar 2023.

HealthMeasures. Patient-reported outcome measurement information system. psychosocial illness impact-negative: HealthMeasures; 2015 [Available from: http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/promis/manuals/PROMIS_Psychosocial_Illness_Impact_Negative_Scoring_Manual.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2023.

Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, Bode R, Peterman A, Heinemann A, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585–95.

Fabbrocini G, Panariello L, De Vita V, Vincenzi C, Lauro C, Nappo D, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a disease-specific questionnaire. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(3):e276–81.

Senna M, Ko J, Glashofer M, Walker C, Ball S, Heredia EE, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients with alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2022.02.019.

King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, Tosti A, Sinclair RD, Ball S, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(4):825–34.

King BA, Mesinkovska NA, Craiglow B, Kindred C, Ko J, McMichael A, et al. Development of the alopecia areata scale for clinical use: results of an academic-industry collaborative effort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(2):359–64.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for taking part in this survey.

Funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company who provided the funding for journal’s Rapid Service Fee. The funder had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing; and decision to submit.

Authorship

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; drafted or critically revised the draft for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Leo J. Philip Tharappel and Hemangi N Rawal of Eli Lilly Services India Private Limited, Bengaluru, India. Data curation and analysis was performed by Evidera. Support for this assistance was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Susan Ball, Sarah G. Smith. Data curation: Not applicable. Formal analysis: Not applicable. Funding acquisition: Susan Ball. Investigation: Susan Ball. Methodology: Susan Ball, Paula Morrow, Sarah G. Smith. Project administration: Susan Ball. Resources: Susan Ball. Software: Not applicable. Supervision: Susan Ball. Validation: Not applicable. Visualization: Susan Ball. Writing—original draft preparation: Susan Ball. Writing—review and editing: Natasha Mesinkovska, Brittany Craiglow, Paula Morrow, Sarah G. Smith, Evangeline Pierce, Jerry Shapiro.

Prior Publication

This manuscript is based on work that has been previously presented/published at Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference—41st Anniversary and encored at American Osteopathic College of Dermatology—2022 Fall Meeting.

Disclosures

Mesinkovska N serves as Chief Scientific Officer for the National Alopecia Areata Foundation and has received honoraria for advisory boards for Arena Pharmaceuticals, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, and Nutrafol. Craiglow B has received honoraria and/or fees from Aclaris Therapeutics Inc, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Sanofi Genzyme; she has served on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. Ball S, Morrow P, and Pierce E are employees of Eli Lilly and Company and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. Smith SG was an employee of Eli Lilly and Company when the study was conducted and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. Shapiro J is a consultant or clinical trial investigator for Pfizer Inc. and a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Patients provided written, informed consent for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals. No personal identifiable information was collected, and all responses were anonymized. The study was reviewed and approved by Advarra Institutional Review Board and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available at Eli Lilly and Company on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mesinkovska, N., Craiglow, B., Ball, S.G. et al. The Invisible Impact of a Visible Disease: Psychosocial Impact of Alopecia Areata. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 1503–1515 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00941-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00941-z