Abstract

Introduction

Although the introduction of biologics and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs) has reshaped the treatment paradigm for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) such as psoriasis, oral conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) remain the cornerstone in their treatment. Combinational use of DMARDs is common in rheumatological practice, but for the treatment of many skin diseases, dermatologists typically use a single oral DMARD, with methotrexate (MTX) being the most commonly prescribed csDMARD for psoriasis.

Methods

To better understand the potential benefits of MTX combination therapy in psoriasis, a literature review was conducted using Medline (PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library, covering articles published from inception until October 2022. Randomized controlled trials, cohort, open-label, and observational studies, and case reports with efficacy and safety results for combination therapy with MTX, csDMARDs, and tsDMARDs or comparisons between MTX monotherapy and combination therapy with other oral DMARDs in psoriasis were included. Studies involving MTX monotherapy alone or sequential treatment with MTX and other oral DMARDs were excluded, as were non-English articles. The results are presented as a systematic review, and the risk of bias was assessed by the corresponding author using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3, and confirmed by an independent assessor.

Results

Eleven studies comprising 494 participants were included in the review. Overall, combination treatment with MTX and other oral DMARDs exhibited good efficacy and tolerability in psoriasis. However, the included studies were primarily small scale or retrospective, and larger prospective randomized trials are needed to provide stronger evidence.

Conclusion

This literature review suggests that combination therapy with MTX and csDMARDs may serve as an efficacious treatment for psoriasis patients with an inadequate response to oral DMARD monotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is an unmet treatment need for the optimal use of conventional oral agents in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, despite the growing use of biologics. |

Methotrexate is the most commonly used oral agent in the treatment of psoriasis. It is usually used as monotherapy, but its efficacy is only moderate compared to biologics in psoriasis. |

This review summarizes pertinent literature concerning the safety and efficacy of the combinational use of methotrexate and other oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in treating psoriasis. |

Cyclosporine, acitretin and apremilast can be added to methotrexate in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate treatment response to oral DMARD monotherapy. |

Introduction

Although the introduction of target therapies, including biologics and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs), has reshaped the treatment of many immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs), oral conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) remain the cornerstone in the treatment of most IMIDs, including psoriasis [1].

Methotrexate (MTX), a synthetic folic acid analog, has been widely used in dermatology practices for over half a century since its first use in psoriasis as an accidental finding by Gubner et al. [2]. MTX acts through competitive inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase and aminoimidazole-carboxamide-ribonucleoside (AICAR) transformylase (ATIC). The inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase prevents the reduction of dihydrobiopterin (BH2) to tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and thus leads to the uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase and T cell apoptosis. The diminished activity of AICAR transformylase causes the adenosine to be released, and the binding of adenosine to cell surface receptors then suppresses many inflammatory and immune reactions [3]. MTX also increases the expression of long intergenic non-coding RNA p21 (lincRNA-p21). LincRNA-p21 is involved in several cellular processes via the regulation of diverse target gene expression, i.e., p21, mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP-K) [4]. By modulating cell-specific signaling pathways, MTX is involved in multiple crucial pro-inflammatory properties of different cell lineages [5]. Owing to its anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative properties, MTX has been used in a variety of skin disorders, including psoriasis [6], pityriasis rubra pilaris [7], chronic urticaria (CU) [8], atopic dermatitis (AD) [9], blistering disorders [10], localized scleroderma [11], dermatomyositis [12], cutaneous sarcoidosis [13], etc.

MTX remains the most commonly prescribed csDMARD for psoriasis [1]. In one meta-analysis published in 2016, 45% of patients receiving MTX therapy achieved a 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area Severity Index score (PASI 75) by 12–16 weeks [14]. It is usually given as monotherapy, but its efficacy is only moderate compared to biologics [15]. Thus, the optimal use of MTX is important in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who failed therapy using biologics or have no access to biologics, mainly due to financial barriers or a lack of reimbursement [16]. Increased oral doses and the use of injection are usually performed to increase the efficacy of MTX [17], but the combination of MTX with other oral DMARDs or biologics can also be attempted [18]. While monotherapy using DMARDs is usually given by dermatology for psoriasis, combinational use of DMARDs is also common in other specialties, including rheumatology [19], transplantation, and gastroenterology (for inflammatory bowel disease). In pivotal studies of biologics in patients with psoriatic arthritis, about 50% of patients received concomitant MTX [20]. In general, biologics plus MTX resulted in better efficacy for psoriasis lesions compared with biologic monotherapy, with no difference in tolerability [21]. In this review, we focus on the efficacy and safety of the combinational use of MTX and other oral DMARDs in the treatment of psoriasis.

Methods

Literature Search

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). We performed a literature search of Medline (PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library with the following keywords: psoriasis, psoriatic, combination, combining, concomitant, add-on, azathioprine, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporine, minocycline, leflunomide, acitretin, apremilast, tofacitinib and upadacitinib (Table 1). The search strategy is displayed in Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria include a diagnosis of psoriasis, combination therapy with MTX, csDMARDs, and tsDMARDs along with available results comparing the efficacy and safety of MTX monotherapy versus combinational therapy with MTX and other oral DMARDs. The primary outcome was the improvement in the severity of psoriasis, such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The secondary outcome was the safety of the combination therapy (both laboratory and clinical parameters).

All original papers in English published from inception until October 2022 were included. The exclusion criteria included studies in which MTX was used as monotherapy, sequential treatment with MTX and other oral DMARDs, an unavailable outcome for the combination treatment (either efficacy or safety), and studies of psoriatic arthritis where the primary outcome was not improvement of psoriatic lesions. There were no limitations regarding the study type and sample size.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

After the searching process, duplicates were removed prior to accessing the full-text articles. Two research personnel (TSH and TFT) independently screened the records.

Any disagreement regarding the selection process between the reviewers was resolved by thorough discussion and a final agreement. One author (TSH) reviewed reference lists and conference abstracts to identify any studies missing from the initial search process.

The data extraction was performed in a standardized manner. The following data were extracted independently by two reviewers (TSH and TFT) from the included studies: author, year of publication, country, study design, case numbers, combination therapy, the dose of combination therapy, the observation periods, the efficacy of the treatment, and the safety outcomes of each study (including lab and clinical abnormalities). In addition, the efficacy of treatment was evaluated using the PASI. In some of these papers, however, the efficacy data were descriptive. Owing to the heterogeneous nature of the studies included, a meta-analysis of the results is not currently feasible.

The results are presented as a systematic review, and the risk of bias was assessed by the corresponding author using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3 (www.training.cochrane.org/handbook, updated February 2022) [22], and confirmed by an independent assessor (not listed as an author; listed in Supplementary Table 1). This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Literature Search

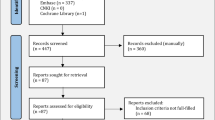

The literature search yielded 1852 articles. After removing duplicates and screening titles/abstracts, we included 338 articles in the full-text review. A total of 267 were then excluded, and 11 studies published from 1990 to 2022 were included in the review. The process of the literature search is listed in the PRISMA flow diagram shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The quality assessment of the included papers is listed in the supplementary tables. The study design included case reports (n = 2), case series (n = 3), retrospective cohort studies (n = 3), prospective cohort studies (n =1), and randomized controlled trials (n = 2). The number of participants included in the studies ranged from 1 to 160 patients. The geographical origins of the studies were diverse, and included the Netherlands, Turkey, India, the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States, China, Thailand and Canada. The observational period ranged from 16 days to 5 years.

Previous Treatment Before Combination Therapy

Before combination therapy, patients were treated with cyclosporin (CsA) monotherapy [23], MTX monotherapy [24, 25], either CsA or MTX as monotherapy [25, 26], or at least one topical/systemic agent [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Reasons for combining with another oral DMARD included an inadequate response to monotherapy or an aim to lower the side effects by using a combination of two DMARDs at lower doses.

Safety and Adverse Events

Overall, combination therapy of MTX with another oral DMARD did not show a significantly higher rate of adverse events compared with MTX monotherapy. However, both combination therapy and monotherapy showed certain percentages of laboratory and/or clinical abnormalities (as listed in Table 2). Thus, regular monitoring for the side effects of each medication is still needed.

Combination Therapy in Psoriasis

In this review, we focus on the efficacy and safety of combination therapy in psoriasis treatment (the results of combination therapy are presented in Table 3).

In studies focusing on psoriasis, combination therapy was used due to an inadequate response to monotherapy. Singh et al. [28] conducted a randomized controlled trial and demonstrated that significantly higher percentages of patients reached PASI 75/90/100 responses at week 12. In other studies, most of the patients’ skin conditions improved under combination therapy.

Cyclosporin in Combination with MTX

Cyclosporin (CsA) is an immunomodulatory agent which inhibits the transcription of interleukin 2 and prevents the activation of T cells. In dermatology, the concurrent use of MTX and CsA was once considered contraindicated in psoriasis due to the shared risk of nephrotoxicity caused by MTX and CsA decreasing each other’s elimination [23]. However, Clark et al. [29] reported the use of combination treatment with CsA and MTX in 19 patients who suffered from severe and recalcitrant psoriasis (most of the patients had previously undergone two or more systemic treatments). Before the combination therapy, the patients were taking the maximum tolerated dose of either CsA or MTX. The combination therapy enabled them to receive each therapy at a lower dose, i.e., a reduction in CsA dose from 4.2 ± 1.2 mg/kg/day to 2.6 ± 0.9 mg/kg/day and a reduction in MTX dose from 21.6 ± 6.7 to 13.9 ± 4.4 mg/week, while still achieving satisfactory results. The duration of the combination ranged from 7 weeks to 500 weeks [29].

Aydin et al. [27] and Mobhanan et al. [25] further conducted prospective and retrospective cohort studies on severe psoriasis patients. In both cohort studies, the results seemed promising and safe for the short-term use of combination therapy. Aydin et al. further conducted a follow-up study of patients from the same cohort who were previously treated with combination therapy and found that 17 out of 20 patients were not diagnosed with cancer (3 were lost to follow-up and the median follow-up period was 76 months). Recently, a randomized, non-blinded, controlled trial demonstrated that combination therapy showed an earlier onset of action compared to MTX monotherapy and to better outcomes for PASI 75, PASI 90, and PASI 100 responses in intention-to-treat analysis, with similar adverse effects to MTX monotherapy [28].

Acitretin in Combination with MTX

Acitretin, a second-generation retinoid, suppresses the proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes, reduces Th1/Th17 inflammatory cell infiltration, and downregulates the expression of interferon-gamma. It is particularly useful for treating pustular psoriasis [36] and palmoplantar psoriasis (10–50 mg daily) [37]. A daily dose starting from 10 mg was found to be effective for the patients [38]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeled the concurrent use of acitretin with MTX as contraindicated based on previous data showing increased rates of hepatitis when using the combination of etretinate and MTX. Acitretin is a metabolite of etretinate, so it is likely to have a similar issue. In this study, only the additive effect of acitretin was considered because etretinate is no longer used in most countries except for Japan. Nevertheless, a study has shown better efficacy and a decreased rate of hepatotoxicity when using this combination therapy, except in patients with alcohol intake [39].

An et al. further performed studies in both humans and mice. The results demonstrated that better skin effects were achieved in the combination group without incurring significantly increased adverse effects on liver function in both humans and mice. In addition, the combination group showed significantly less elevation of the laminin level in hepatic stellate cells (MTX: 69.70 μg/L; combination therapy of MTX and acitretin: 27.54 μg/L, P < 0.05) [40]. The results were also supported by a real-life registry showing a similar incidence of hepatic fibrosis as determined by transient elastography in a MTX monotherapy group and a group concurrently using both MTX and acitretin. Instead, the risk factors for hepatic fibrosis identified in that retrospective cohort study were type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity [41].

Apremilast in Combination with MTX

Apremilast, a small molecular inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), modulates the innate immune system by increasing the intracellular cAMP level, leading to a reduction in interferon-α production and T cell cytokines [42]. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and oral ulcers in Behcet’s syndrome [43].

Abuhilal et al. [33] conducted a retrospective study that included 81 patients with plaque psoriasis treated with a combination therapy of apremilast and at least one other therapy (NB-UVB, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporin, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab or ustekinumab). Overall, 81% of patients achieved a PASI 75 response at week 12 after the combination therapy. Among the combination therapies, 15 patients were on the combination therapy of MTX and apremilast and had an average improvement in PASI score from 8.7 before the addition of apremilast to 2.8 at week 12.

Real-world experience of apremilast for psoriasis in Canada demonstrated that out of 81 patients who were treated with apremilast, 6 patients were on combination therapy of MTX and apremilast; nevertheless, the article didn’t specify the efficacy of MTX combination therapy with apremilast [44].

Discussion and Conclusion

The use of combinational csDMARDs therapy by rheumatologists [45] for various IMIDs, including psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, is common. Triple therapy of hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and MTX is not only as effective as [46] but also safer than [47] etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. It is also more cost effective [48] and has better drug survival [49]. A combination of leflunomide and MTX was also shown to have biologic-sparing effects in refractory rheumatoid arthritis [50].

The dose of immunosuppressants is also crucial in determining its effect on the immune system. Taking CsA for example, CsA at a higher dose is immunosuppressive, but lower-dose CsA has immunomodulatory, anti-graft-versus-host, and anti-cancer effects [51]. In general, doses below 3 mg/kg/day are regarded as low doses, and doses above 4 mg/kg/day can be defined as high doses [51]. In patients with atopic dermatitis, low-dose CsA increased [52] while high-dose CsA reduced [53] the T-reg population. In addition, CsA commonly serves as a rescue therapy in severe psoriasis patients to achieve a rapid treatment response and is commonly used in pregnant women (although it is listed as a pregnancy category C drug) due to its relative safety compared to other oral DMARDs. It is known for adverse events such as nephrotoxicity (interstitial fibrosis and renal tubular atrophy), hypertension, and an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma/lymphoproliferative disorders [54]. CsA added to MTX treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis patients significantly increased the peak plasma MTX concentration, but other pharmacokinetic parameters and measurements of MTX were unchanged [55]. A similar concept of a dose-related effect for MTX was also proved in the Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA) trial, in which higher proportions of patients receiving over 15 mg of MTX per week achieved an American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response (41% versus 34%) [56].

The combination of MTX with other oral DMARDs used in dermatology, especially in psoriasis, is relatively uncommon. Based on the current literature review, the combination of MTX with either csDMARDs or tsDMARDs may provide additional therapeutic benefits compared with MTX monotherapy. Current literature on the combination of MTX with other oral DMARDs remains limited. However, based on this review, the combination of MTX with other oral DMARDs seemingly does not significantly increase safety concerns compared to MTX monotherapy.

Theoretically, side effects may be reduced if the combination therapy successfully lowers the dosage of the individual drug compared to when it is used as monotherapy [57]. This was demonstrated by the significant lowering of profibrotic factors such as laminin in the combination group versus the MTX group [40]. Hepatic fibrosis was a major concern during MTX treatment, and in one retrospective cohort study, the incidence of hepatic fibrosis during MTX monotherapy was not significantly different compared to that during combination therapy with acitretin and MTX (16.4% in the monotherapy group vs. 12.5% in the combination group, P = 0.59) [41].

Although no significant increases in adverse events were observed during combination therapy with MTX and other oral DMARDs, the clinician should be alert to the potential side effects of each DMARD and follow the laboratory data according to the known adverse events. The main safety concerns in laboratory data are still liver toxicity and a deterioration of kidney function (as in MYX combination therapy with CsA). The major clinical adverse effects are gastrointestinal discomfort (nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal discomfort, and anorexia). Still, constitutional symptoms, mental problems (anxiety/insomnia), and infection are also reported.

There are several limitations of our study. Except for some controlled trials [28, 40], most studies were small case series, and most of the current literature has limitations regarding sample size, study design, follow-up period, etc. Racial factors are also worth taking into account: different racial factors have been found to affect the drug metabolism, efficacy and safety of oral immunomodulatory agents in psoriasis [58,59,60]. However, their effect on the combinational use of oral DMARDs in psoriasis has not been specifically studied. In addition, there were also several limitations regarding methodology, i.e., the restriction to English publications and the limited database search.

Although biologics have become the gold standard in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, the high cost of biologics has limited the number of patients who can be treated with them. In many parts of the world, there are still significant barriers to using biologics due to a reimbursement requirement for economic reasons. This is especially true for patients who have a Body Surface Area (BSA) or PASI of less than 10 but still have a significantly impacted quality of life. Thus, for these patients, the combinational use of two oral conventional DMARDs might be needed.

Also, despite their relative safety with regard to major organ toxicities, biologics present a potential concern due to an increased risk of infection and decreased efficacy after long-term use. Theoretically, the combination of csDMARDs with different modes of action has potential benefits in terms of increasing treatment efficacy and improving biologic survival.

In conclusion, the concurrent use of MTX with other oral DMARDs might optimize the treatment potential of MTX in psoriasis. It is especially valuable for patients who have no access to biologics due to financial barriers or an ineligibility for reimbursement. However, while its benefits have been partially demonstrated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, more studies are still needed to confirm them in psoriasis.

References

Chang YT, Chen TJ, Liu PC, Chen YC, Chen YJ, Huang YL, et al. Epidemiological study of psoriasis in the national health insurance database in Taiwan. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89(3):262–6.

Gubner RS. Introduction of antifolics in psoriasis. A twenty-five year retrospect of antineoplastic agents in nonmalignant disease. Cutis. 1979;23(4):425–8.

Hannoodee M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2022.

Tang SS, Zheng BY, Xiong XD. LincRNA-p21: implications in human diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(8):18732–40.

Cronstein BN, Aune TM. Methotrexate and its mechanisms of action in inflammatory arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(3):145–54.

Dogra S, Mahajan R. Systemic methotrexate therapy for psoriasis: past, present and future. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38(6):573–88.

Koch L, Schoffl C, Aberer W, Massone C. Methotrexate treatment for pityriasis rubra pilaris: a case series and literature review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):501–5.

Sandhu J, Kumar A, Gupta SK. The therapeutic role of methotrexate in chronic urticaria: a systematic review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;88(3):313–21.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–78.

Gurcan HM, Ahmed AR. Analysis of current data on the use of methotrexate in the treatment of pemphigus and pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(4):723–31.

Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Treatment of scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(1):99–105.

Kasteler JS, Callen JP. Low-dose methotrexate administered weekly is an effective corticosteroid-sparing agent for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(1):67–71.

Lower EE, Baughman RP. The use of low dose methotrexate in refractory sarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci. 1990;299(3):153–7.

West J, Ogston S, Foerster J. Safety and efficacy of methotrexate in psoriasis: a meta-analysis of published trials. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5): e0153740.

Sbidian E, Chaimani A, Garcia-Doval I, Doney L, Dressler C, Hua C, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD011535.

Eissing L, Radtke MA, Zander N, Augustin M. Barriers to guideline-compliant psoriasis care: analyses and concepts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(4):569–75.

Franova J, Fingerhutova S, Kobrova K, Srp R, Nemcova D, Hoza J, et al. Methotrexate efficacy, but not its intolerance, is associated with the dose and route of administration. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):36.

Gyldenlove M, Alinaghi F, Zachariae C, Skov L, Egeberg A. Combination therapy with apremilast and biologics for psoriasis: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(5):605–13.

Katchamart W, Trudeau J, Phumethum V, Bombardier C. Efficacy and toxicity of methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy versus MTX combination therapy with non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1105–12.

Sin CZ, Wang TS, Chiu HY, Tsai TF. Human leukocyte antigen and demographic characteristics in Chinese patients with active peripheral type psoriatic arthritis who had inadequate response to conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in a single dermatologic clinic. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1): e0210076.

Xie Y, Liu Y, Liu Y. Are biologics combined with methotrexate better than biologics monotherapy in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(3): e14926.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.3 (updated February 2022). London: Cochrane; 2022.

Korstanje MJ, van Breda Vriesman CJ, van de Staak WJ. Cyclosporine and methotrexate: a dangerous combination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2 Pt 1):320–1.

Fraser AD, van Kuijk AW, Westhovens R, Karim Z, Wakefield R, Gerards AH, et al. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre trial of combination therapy with methotrexate plus ciclosporin in patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):859–64.

Mohanan S, Ramassamy S, Chandrashekar L, Thappa DM. A retrospective analysis of combination methotrexate-cyclosporine therapy in moderate-severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(1):50–3.

Wong KC, Georgouras K. Low dose cyclosporin A and methotrexate in the treatment of psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79(1):87.

Aydin F, Canturk T, Senturk N, Turanli AY. Methotrexate and ciclosporin combination for the treatment of severe psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):520–4.

Singh SK, Singnarpi SR. Safety and efficacy of methotrexate (0.3 mg/kg/week) versus a combination of methotrexate (0.15 mg/kg/week) with cyclosporine (2.5 mg/kg/day) in chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised non-blinded controlled trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87(2):214–22.

Clark CM, Kirby B, Morris AD, Davison S, Zaki I, Emerson R, et al. Combination treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporin for severe recalcitrant psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(2):279–82.

Lowenthal KE, Horn PJ, Kalb RE. Concurrent use of methotrexate and acitretin revisited. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19(1):22–6.

Shivers L, Montanez-Wiscovich ME. Verrucous psoriasis treated with methotrexate and acitretin combination therapy. Cutis. 2019;104(6):E10–2.

Asiri A, Thavaneswaran A, Kalman-Lamb G, Chandran V, Gladman DD. The effectiveness of leflunomide in psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(5):728–31.

AbuHilal M, Walsh S, Shear N. Use of apremilast in combination with other therapies for treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(4):313–6.

Kivitz AJ, FitzGerald O, Nash P, Pang S, Azevedo VF, Wang C, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib by background methotrexate dose in psoriatic arthritis: post hoc exploratory analysis from two phase III trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(2):499–511.

Nash P, Richette P, Gossec L, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy and in combination with non-biologic DMARDs for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: subgroup analysis from two phase 3 trials (POS1035). In: EULAR 2021 Virtual Congr; 2021 June 2–5.

Carretero G, Ribera M, Belinchon I, Carrascosa JM, Puig L, Ferrandiz C, et al. Guidelines for the use of acitretin in psoriasis. Psoriasis Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104(7):598–616.

Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. Berlin: StatPearls; 2021.

Kolalapudi SA, editor. Efficacy of low-dose acitretin in palmoplantar psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:AB124.

Gronhoj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, Hjorter A, Brockhoff PB, Nielsen-Kudsk F. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(6):1164–9.

An J, Zhang D, Wu J, Li J, Teng X, Gao X, et al. The acitretin and methotrexate combination therapy for psoriasis vulgaris achieves higher effectiveness and less liver fibrosis. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:158–68.

Rattanakaemakorn P, Pinyowiwat P, Iamsumang W, Chanprapaph K, Suchonwanit P. Incidence and risk factors of hepatic fibrosis in psoriatic patients receiving methotrexate with concomitant acitretin therapy and methotrexate monotherapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:2299–307.

Schafer PH, Parton A, Capone L, Cedzik D, Brady H, Evans JF, et al. Apremilast is a selective PDE4 inhibitor with regulatory effects on innate immunity. Cell Signal. 2014;26(9):2016–29.

Nassim D, Alajmi A, Jfri A, Pehr K. Apremilast in dermatology: a review of literature. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e14261.

Mayba JN, Gooderham MJ. Real-world experience with apremilast in treating psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21(2):145–51.

Inui K, Koike T. Combination therapy with biologic agents in rheumatic diseases: current and future prospects. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2016;8(5):192–202.

Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Paulus HE, Curtis JR, Bathon JM, St Clair EW, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis: the Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(9):2824–35.

Quach LT, Chang BH, Brophy MT, Soe Thwin S, Hannagan K, O’Dell JR. Rheumatoid arthritis triple therapy compared with etanercept: difference in infectious and gastrointestinal adverse events. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(3):378–83.

Bansback N, Phibbs CS, Sun H, O’Dell JR, Brophy M, Keystone EC, et al. Triple therapy versus biologic therapy for active rheumatoid arthritis: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):8–16.

Peper SM, Lew R, Mikuls T, Brophy M, Rybin D, Wu H, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis treatment after methotrexate: the durability of triple therapy versus etanercept. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(10):1467–72.

Hodkinson B, Magomero KR, Tikly M. Combination leflunomide and methotrexate in refractory rheumatoid arthritis: a biologic sparing approach. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2016;8(5):172–9.

Flores C, Fouquet G, Moura IC, Maciel TT, Hermine O. Lessons to learn from low-dose cyclosporin-A: a new approach for unexpected clinical applications. Front Immunol. 2019;10:588.

Brandt C, Pavlovic V, Radbruch A, Worm M, Baumgrass R. Low-dose cyclosporine A therapy increases the regulatory T cell population in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64(11):1588–96.

Hijnen D, Haeck I, van Kraats AA, Nijhuis E, de Bruin-Weller MS, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Cyclosporin A reduces CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T-cell numbers in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(4):856–8.

Strober BE. Methotrexate and cyclosporine in psoriasis revisited. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33(2 Suppl 2):S27-30.

Odderskov C, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Ellingsen T, Hornung N. Methotrexate pharmacokinetic is influenced by co-administration of cyclosporin in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Results from a randomized clinical trial. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2020;80(3):185–90.

Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Methotrexate efficacy in the tight control in psoriatic arthritis study. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(2):356–61.

Armstrong AW, Bagel J, Van Voorhees AS, Robertson AD, Yamauchi PS. Combining biologic therapies with other systemic treatments in psoriasis: evidence-based, best-practice recommendations from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):432–8.

Yeo CM, Chong VH, Earnest A, Yang WL. Prevalence and risk factors of methotrexate hepatoxicity in Asian patients with psoriasis. World J Hepatol. 2013;5(5):275–80.

Dirks NL, Huth B, Yates CR, Meibohm B. Pharmacokinetics of immunosuppressants: a perspective on ethnic differences. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;42(12):701–18.

Chernov A, Kilina D, Smirnova T, Galimova E. Pharmacogenetic study of the impact of ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the response to cyclosporine in psoriasis patients. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(11):2441.

Aydin F, et al. Methotrexate and ciclosporin combination for the treatment of severe psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):520–4.

Mohanan S, et al. A retrospective analysis of combination methotrexate-cyclosporine therapy in moderate-severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(1):50–3.

Clark CM, et al. Combination treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporin for severe recalcitrant psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(2):279–82.

An J, et al. The acitretin and methotrexate combination therapy for psoriasis vulgaris achieves higher effectiveness and less liver fibrosis. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:158–68.

Rattanakaemakorn P, et al. Incidence and risk factors of hepatic fibrosis in psoriatic patients receiving methotrexate with concomitant acitretin therapy and methotrexate monotherapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021;15:2299–307.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or the publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Tsen-Fang Tsai; methodology: Tsen-Fang Tsai and Tyng-Shiuan Hsieh; formal analysis and investigation: Tsen-Fang Tsai and Tyng-Shiuan Hsieh; writing—original draft preparation: Tyng-Shiuan Hsieh; writing—review and editing: Tsen-Fang Tsai; supervision: Tsen-Fang Tsai.

Disclosures

Tsen-Fang Tsai and Tyng-Shiuan Hsieh declare that they have no competing interests. Tsen-Fang Tsai has conducted clinical trials or received honoraria for serving as a consultant for AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GSK-Stiefel, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Merck, Novartis, PharmaEssentia, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma and UCB.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsieh, TS., Tsai, TF. Combination Therapy for Psoriasis with Methotrexate and Other Oral Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 891–909 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00903-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00903-5