Abstract

Contrary to the popular view that the U.S. welfare system has been in a contractionary phase after the expansions of the welfare state in the 1960s, welfare spending resumed steady growth after a pause in the 1970s. However, although aggregate spending is higher than ever, there have been redistributions away from non-elderly and nondisabled families to families with older adults and to families with recipients of disability programs; from non-elderly, nondisabled single-parent families to married-parent families; and from the poorest families to those with higher incomes. These redistributions likely reflect long-standing, and perhaps increasing, conceptualizations by U.S. society of which poor are deserving and which are not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 16 are the Old-Age Survivors Insurance program (i.e., Social Security retirement), Medicare, UI, Workers Compensation, SSDI, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, AFDC-TANF, the EITC, the CTC, Food Stamps, subsidized housing programs, school food programs, WIC, and Head Start. The one important set of programs that is left out for lack of good data are child care programs.

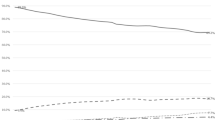

The annualized rates of growth in the three periods are 10 %, 2 %, and 2.6 %, respectively.

Spending in the third period also rose relative to gross domestic product (GDP), from 9 % of GDP in 1985 to 12 % in 2007, a significant and nontrivial increase.

Part of this growth is a result of increases in medical care prices, which were rising faster than general inflation over this period. These figures deflate spending by a general price index and hence overstate the growth of real medical care utilization.

Some of the decline in spending after 1996 has been attributed to the decline of the AFDC-TANF program as well given that many recipients of that program prior to 1996 had been automatically eligible for Food Stamps.

The programs include Social Security retirement, SSDI, Workers Compensation, UI, AFDC-TANF, Food Stamps, SSI, subsidized housing, veterans benefits, WIC, General Assistance, Other Welfare, the EITC, and the CTC.

Because I modified the price index and a few of the details of their calculations, these figures will not exactly match those in their published study.

It would be preferable to define a disabled population independent of benefit receipt, but the questions on disability in the SIPP data are not adequate to do so.

The data on cohabitation in the 1983 SIPP are inadequate, so marriage is used to define the first two groups. Families with children are those with children under age 18 in the household.

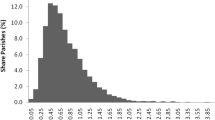

The percentage of single mothers in the income groups did change somewhat over the period. In 1983, the percentage of families in the four groups (of those with private income less than 200 % of the poverty threshold) from lowest to highest were 53 %, 16 %, 16 %, and 14 %, and they had changed to 41 %, 22 %, 21 %, and 16 % by 2004.

There are many fewer married-parent families in deep poverty: 20 % in 1983 and 17 % in 2004.

Separate tabulations for childless individuals and married childless families show similar, small changes.

Some other past research on related topics provides complementary evidence. A literature on “disconnected” families shows a rising fraction of low-income families who have little or no earnings as well as little or no cash welfare (Blank and Kovak 2009; Loprest 2011). Shaefer and Edin (2013) showed an increase in the number of families with incomes less than $2 per day, which is partly a result of these declines in government assistance for the poorest families.

References

Ben-Shalom, Y., Moffitt, R., & Scholz, J. K. (2012). An assessment of the effectiveness of antipoverty programs in the United States. In P. Jefferson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty (pp. 709–749). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Berkowitz, E. (2000). Disability policy and history. Statement before the subcommittee on social security of the committee on ways and means.

Blank, R. M., & Kovak, B. K. (2009). The growing problem of disconnected single mothers. In C. J. Heinrich & J. K. Scholz (Eds.), Making the work-based safety net work better (pp. 227–258). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Burkhauser, R. V., Larrimore, J., & Simon, K. (2013). Measuring the impact of valuing health insurance on levels and trends in inequality and how the Affordable Care Act of 2010 could affect them. Contemporary Economic Policy, 31, 779–794.

Burtless, G., & Svaton, P. (2010). Health care, health insurance, and the distribution of American incomes. Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 13(1), 1–39.

Daly, M. C., & Burkhauser, R. V. (2003). The supplemental security income program. In R. Moffitt (Ed.), Means-tested transfers in the United States (pp. 79–139). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Edin, K., & Lein, L. (1997). Making ends meet: How single mothers survive welfare and low-wage work. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Garfinkel, I., & McLanahan, S. S. (1986). Single mothers and their children: A new American dilemma. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Grogger, J., & Karoly, L. A. (2005). Welfare reform: Effects of a decade of change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harrington, M. (1962). The other America: Poverty in the United States. Baltimore, MD: Penguin.

Iceland, J. (2013). Poverty in America: A handbook (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jencks, C. (1992). Rethinking social policy: Race, poverty, and the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Katz, M. B. (1989). The undeserving poor: From the war on poverty to the war on welfare. New York, NY: Pantheon.

Loprest, P. J. (2011). Disconnected families and TANF (Brief No. 2). Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

McGarry, K. (2013). The safety net for the elderly. In M. J. Bailey & S. Danziger (Eds.), Legacies of the war on poverty (pp. 179–205). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

Meyer, B. D., Mok, W. K. C., & Sullivan, J. X. (2009). The under-reporting of transfers in household surveys: Its nature and consequences (NBER Working Paper No. 15181). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Moffitt, R. A. (1998). The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In R. A. Moffitt (Ed.), Welfare, the family, and reproductive behavior (pp. 50–97). Washington, DC: National Research Council.

Moffitt, R. A. (2013). The great recession and the social safety net. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 650, 143–166.

Moffitt, R. A., Phelan, B., & Winkler, A. (2015). Welfare rules, incentives, and family structure (Working paper). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

Murray, C. (1984). Losing ground: American social policy, 1950–1980. New York, NY: Basic.

Patterson, J. T. (1994). America’s struggle against poverty, 1900–1994. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Preston, S. H. (1984). Children and the elderly: Divergent paths for America’s dependents. Demography, 21, 435–457.

Shaefer, H. L., & Edin, K. (2013). Rising extreme poverty in the United States and the response of means-tested transfer programs. Social Service Review, 87, 250–268.

Spar, K. (2006). Cash and noncash benefits for persons with limited income: Eligibility rules, recipient, and expenditure data, FY2002–2004. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Acknowledgments

This article is a revised version of Presidential Address to the Population Association of America, Boston, May 2, 2014. I thank Andrew Cherlin, Kathryn Edin, and other participants of a seminar at the Hopkins Population Center, as well as Sandra Hofferth, Michael Rendall, and other participants of a seminar at the Maryland Population Research Center for comments. Nadia Diamond-Smith and Gwyn Pauley provided excellent research assistance. Financial support from the Russell Sage Foundation is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moffitt, R.A. The Deserving Poor, the Family, and the U.S. Welfare System. Demography 52, 729–749 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0395-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0395-0