Abstract

Marine litter, and plastics in particular, is fast rising to the top of the political agenda at all levels of governance. The popular phrase today, evoked at all political meetings, in all speeches and at all cocktail parties, is that by 2050, there will be more plastics than fish in the ocean. This is a simple and valid prediction naturally, since global fish stocks are fished at capacity and therefore not increasing in number—whereas the inflow of plastics into the ocean is continuous and rising. Stopping litter from entering the marine ecosystem is therefore the logical step to stop the prediction from coming true. Do we have time to wait for the international community to come together to ratify a treaty text on this, with the required years of negotiations in between, though? Granted, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) passed 13 nonbinding resolutions in December of 2017 of which one was on marine microplastics. They are still nonbinding though and without any teeth or financial instruments attached. The General Assembly, however, adopted resolution 72/249 also in December 2017, on a conference spanning a 2-year period, starting in 2018, where the end goal is to agree on a treaty on the protection of biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). We argue in this article that, rather than waiting for a treaty that is plastics specific, a path to fast action could be to incorporate this into these negotiations, since plastic is interweaved as a substantial stressor to the system and to biodiversity in all areas of the ocean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) made a major shift in international maritime law by establishing a 12 nautical mile territorial sea and the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zones (EEZ), effectively privatizing large portions of the oceans. One of the known weaknesses of UNCLOS, however, was that the high seas, or the areas outside national jurisdiction, still were free for all to use and abuse. At the 2010 meeting of the Convention of Biological Diversity, member states made a commitment to conserve 10% of marine environments globally to protect these areas from over exploitation (De Santo 2013). Currently, only 2.3% is protected though (De Santo 2013), and even the 10% figure might not be enough protection (IUCN 2016). Recognizing these limitations, the United Nations General Assembly created a working group to discuss this topic during their 59th session in 2004, and this ad hoc working group met nine times between 2006 and 2016 to prepare for a negotiation conference for a treaty to govern marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (commonly abbreviated as the BBNJ Conference), and where an emphasis would be on among others marine protected areas (Druel et al. 2013).

An increasing number of articles discuss the process leading up to the BBNJ Conference from different vantage points, looking at the different packages, institutional angles, geographical implications, and interplay with other regimes specifically (Warner 2012; Druel and Gjerde 2014; Warner 2015; Blasiak et al. 2016, 2017; De Lucia 2017; O'Leary and Roberts 2017; Harden-Davies 2018; Mossop 2018). We focus on marine plastics, an increasingly publicized environmental challenge that may act as an exogenous factor to facilitate the negotiation process and act as a binding catalyst for a final agreement. We compare the environmental challenge of marine plastics to the effect that the ozone hole had on the treaties of the ozone regime and that of the black forest deaths on the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, as these latter two illustrate the effect of exogenous factors having a strong effect on treaties. Though plastic itself is not a specific prioritized part of the BBNJ “package,” it is interwoven as a substantial stressor to the ecosystem and to biodiversity in all areas of the ocean. As such, marine plastics could serve as a needed environmental impetus for action for the proposed BBNJ treaty, and its inclusion as an issue in the BBNJ Conference could serve as an effective way to address this important issue through a major multilateral treaty.

The BBNJ Conference and marine plastics

The decision to start discussing governance limitations in large parts of the oceans under UNCLOS came within the context of local, regional, and global environmental challenges. These challenges demonstrated the necessity of joint efforts between state and non-state actors as parties to multilateral environmental agreements. These environmental challenges included, among others, human explorations into the high seas and deep seabed, the 64% of the global ocean that is located in what are formally called areas beyond national jurisdiction. In these areas, scientific discoveries have recently identified seamounts, hydrothermal vents, and cold-water corals in rare and vulnerable ecosystems, as well as the potentials of marine genetic resources that could be exploited in a number of industries (Dunn et al. n.d.). These resources, and others unknown yet, may be of substantial economic value for states with the technological opportunities to explore these.

Concern over the contradictions in terms of sustainable development and conservation efforts in these areas has increasingly become vocal, and the United Nations General Assembly therefore called for an intergovernmental negotiation process towards a new multilateral treaty in Resolution 69/292, adopted in June 2015, on marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. The process transparency was guaranteed by allowing non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) to contribute in the discussions of a preparatory committee (PrepCom). This PrepCom was established to prepare substantial recommendations for the treaty text before actual negotiations took place. The PrepCom determined four issues that were at the core of the future treaty: (1) marine genetic resources including questions of benefit sharing, (2) environmental impact assessments, (3) area-based management tools (including marine protected areas), and (4) capacity building and technology transfer.

On December 24, 2017, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 72/249 entitled “International legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction.” This resolution set up the process for formal negotiations on the BBNJ issue. Interested parties will meet for an organizational meeting in April 2018, with the first formal negotiations beginning in September 2018. In total, the conference will be held in four sessions, with the final meeting taking place in the first half of 2020 (United Nations General Assembly 2017). The resultant treaty will act both as a conservation and governance mechanism, meant to establish methods to protect marine biodiversity and provide guidelines to regulate the human exploitation of the resources in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction.

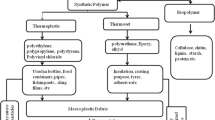

One major challenge to marine ecosystems comes from the proliferation of plastics in the ocean. Marine plastic pollution is increasing in concert with the production of plastics, naturally. This production has increased from 1.7 million tons in the 1950s until it reached 299 million tons in 2013, with 4% of global petroleum production being used to create the material (Gourmelon 2015). The concept of plastics is often fuzzily described in popular media, with references to microplastics intermingled with that of plastic litter in general. Primary microplastics are particles in the size range of < 5 mm that derive directly from consumer products, such as scrub creams or toothpaste (Andrady 2011). The creation of secondary microplastics—that have the same size as that of its primary equivalent—results from the breakdown and wear of plastic consumer goods, for instance, textiles, paints, and car tires, or breakdown of so-called oxo-degradable plastic bags, which are in fact intentionally designed to rapidly fragment into microplastic particles (Law and Thompson 2014; Kubowicz and Booth 2017). Plastics are of concern because they have been discovered in all marine environments, including the Arctic and other remote parts of the earth (Baztan et al. 2017; Cózar et al. 2017).

The size and abundance of plastics in the marine environment globally expose marine biodiversity to potential dangers. Larger pieces or macroplastics are esthetically dramatic and prove tragic to the marine mammals and seabirds that get entangled or maimed by these patches of litter. However, these only represent about 1% of all plastics in the ocean. Microplastics are much more plentiful and are readily ingested by many marine organisms because of their size. This increases the exposure to all marine species and the subsequent risk for negative impacts on the environment. It also potentially poses risks to humans through the ingestion of food from marine sources, such as fish, crustaceans, and plants—though the number of studies specifically reporting impacts associated with such ingestion is small and uncertainty is high (Wright et al. 2013; Anderson et al. 2016; Rochman et al. 2016; Barboza et al. 2017; Law 2017; Wright and Kelly 2017). Ninety-four percent of all marine plastics litter the bottom of the ocean and the remaining 5% litter the beaches of the world (Sherrington 2016). As such, the popular phrase that by 2050 there will be more plastics than fish in the ocean is true—but very little of it will be visible to the naked eye.

The state of affairs in the governance of marine plastics

The fact that the majority of plastics litter the bottom of the ocean does not make it any less tragic to life in the ocean, since there are unknown consequences of this deposit of plastics in our environment. The visibility of the marine garbage patches and deaths of marine mammals have ensured that this environmental challenge has reached the top of the political agenda throughout the globe, with resultant outrage from the public. Several initiatives have followed in many different nations around the world. In Norway, for instance, the Norwegian Environment Agency (Miljødirektoratet) published a study named Primary microplastic-pollution: Measures and reduction potentials in Norway in 2016, identifying sources of microplastic pollution, and proposed measures for curbing it, among others, through the pathway of wastewater and sewage plants (Sundt et al. 2016). In the USA, the emphasis was on the presence of microplastics in consumer products such as scrub creams, leading to the passage of the Microbead-Free Waters Act at the New York State Assembly by a vote of 108 to 0 in 2014, effectively prohibiting the distribution and sale of cosmetic products that contain plastic microbeads. This was followed by other states such as California following suit, and several more introducing similar bills for debate. The next year, the Congress passed The Microbead-Free Water Act of 2015, signed into law by President Barack Obama, which puts a national “... ban [on] rinse-off cosmetics that contain intentionally-added plastic microbeads beginning on January 1, 2018, and to ban manufacturing of these cosmetics beginning on July 1, 2017. These bans are delayed by one year for cosmetics that are over-the-counter drugs.” (114th Congress 2015).

Similar regional and national bans on plastics have appeared in other countries as well. The UK voted to ban microbeads in September 2016, a law that came into force on January 1, 2018. Within Indonesia, the Bali government has made a commitment to ban plastic bags by 2018. Ghana plans to eliminate marine plastics from its coasts by 2025 (Earth Negotiations Bulletin 2017). At the European level, the European Union Marine Strategy Framework Directive specifically defines microplastics as litter and commits all its member states to establish and implement mitigation measures to reduce this source of litter by 2020. In January 2018, the EU published its plastic strategy which aims to transform the way products are designed, produced, used, and recycled in the EU so that the 30% recycling rate can be increased dramatically (European Commission 2018). Both France and Italy have bans on plastic bags, as do the African countries of Rwanda and Kenya. The latter two are taking their plastic bag bans very seriously, with public shaming, fines, and jail time as possible preventive measures against its use (Freytas-Tamura 2017a, 2017b).

There has also been movement at a global level towards working together to solve the challenge of marine plastics. On February 23, 2017, the UN Environment Programme launched a campaign to eliminate microplastics in cosmetic single-use plastics in general by 2022, while at the same time launching the hashtag #CleanSeas (UNEP 2017a). At the close of the UN Environment Assembly in Nairobi in December of 2017, the world committed to a pollution-free planet and passed 13 nonbinding resolutions (UNEP 2017b), whereof one specifically deals with microplastics in the marine environment, signed by all 193 nations present at the meeting and a clear step towards global management of the challenge (Ndiso 2017, UNEP 2017c). In addition, the Sustainable Development Goals, specifically Goal 14 on life under water, specifically mention the reduction of marine pollution by 2025 as one of its targets (United Nations 2016). Nevertheless, the governance initiatives are still largely fragmented, with parallel runs taking place even at the UN level, and the collaborations of efforts between nations on the topic are few.

Marine plastics as an exogenous factor for the BBNJ negotiations

As such, despite these global, national, regional, and private initiatives to remove plastic microbeads from products or marine litter from the oceans in general, there is currently no comprehensive global legislation limiting their use or addressing the real challenge of actually stopping the flow of plastics into the ocean. Because, the fact is, the reason there will be more plastics than fish in the ocean by 2050 is quite simple—the amount of fish in the ocean is not expected to rise. In fact, since only about 10% of global fish stocks are underfished, the amount of fish in the ocean is more likely to fall than anything else (FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture department 2016). In the meantime, there is still no comprehensive effort to stop the massive inflow of plastics into the global oceans, meaning that plastic pollution is likely to keep rising.

We have already argued that the BBNJ treaty could be a vehicle of fast action for global plastic management. Though the treaty is not international law yet, it is in a process in which its text could be altered through institutional layering or conversion (Thelen 2003; Thelen 2004). With layering, new elements could be grafted onto existing frameworks such as that of the BBNJ package, or new rules or goals could be adapted into the institution through conversion. In the latter case, the historic function of the institution is converted along with the role of the institution, which in this hypothetical case could be inclusive of a global effort to reduce marine plastic inflow. Neither is possible without the issue having a large public interest and urgency, resulting in public pressure for political action. This urgency will usually derive from perceptions of hazard or risk to oneself or something one cares about, and often the levels of risk must be considered catastrophic and be backed both by scientific evidence and global consensus that this is a threat to people as well. And most importantly, it has to be possible to observe the threat, giving the public a sense of immediacy and increasing the perceptions of exposure risk (Morrisette 1989). When in addition there is an appearance of accepted leadership to move an agreement forward to reach a global agreement that is of higher value than that of fragmented efforts (Sliggers et al. 2004), layering or conversion is both possible.

The effects of the death of trees in the Black Forest in Germany on the 1979 Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) can be an illustrative example. This treaty was based on a cooperation between 49 parties that were members of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, and it was originally formed because of concerns over acid rain resulting from sulfur oxide emissions and a necessity of reducing SO2. Originally, this environmental challenge was limited to evidence of acidification of lakes and rivers in Scandinavia, sponsored by Norway and Sweden with the Soviet Union as an ally. Moreover, the original agreement lacked concrete measures to actually limit the damage of acid rain at a larger scale since European nations were not taking it seriously enough (Levy 1995; Sliggers et al. 2004). From 1982 onwards, however, it became clear to other nations as well through the deaths of the German forests—“Waldsterben”—that long-range air pollution was a serious problem, resulting in the 1985 Sulphur Protocol, which effectively changed the functionality of the LRTAP regime through institutional conversion.

In the LRTAP case, the regime changed due to the layering of the 1985 Sulphur Protocol with binding targets on a specific pollutant. This alteration came about because perceptions of the public changed, with the deaths of the Black Forest trees adding an urgency to finding a solution to this particular environmental problem. Marine plastics could potentially serve the same role for the proposed BBNJ treaty by layering on an additional piece to the package at the early stage of negotiations because of its immediacy in public perceptions and social media coverage. Marine plastic pollution does not have to wait for perceptions of global impact to reach the consciousness of the public, or for individuals to demand political action. The issue is already at the top of the agenda in many countries, is highly visible and clearly observed (at least macroplastic pollution), and holds a temporal immediacy to the public through the repetition of the “more plastics than fish in the ocean by 2050” statements. What the plastic challenge needs is an arena for global leaders to negotiate a global solution that is available and temporally close in time, and that bears with it the legality that shows some teeth when it comes to compliance. The upcoming BBNJ negotiations are such an arena, with a set deadline of 2 years of negotiations. Do we have time to wait for a parallel initiative, or is this the time and the place to stop the inflow of marine plastic pollution to already vulnerable marine ecosystems in areas within and beyond natural jurisdiction?

References

114th Congress (2015) Microbead-free waters act of 2015. H.R.1321. House—energy and commerce. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1321?resultIndex=2

Anderson JC, Park BJ, Palace VP (2016) Microplastics in aquatic environments: implications for Canadian ecosystems. Environ Pollut 218:269–280

Andrady AL (2011) Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar Pollut Bull 62(8):1596–1605

Barboza LGA et al (2017) Marine pollution by microplastics: environmental contamination, biological effects and research challenges. World seas: an environmental evaluation, Vol III: Ecological issues and environmental impacts. C. Sheppard, Elsevier. In Press

Baztan J et al (2017) Breaking down the plastic age. Fate and impact of microplastics in marine ecosystems, Elsevier, pp 177–181

Blasiak R et al (2016) Negotiating the use of biodiversity in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction. Front Mar Sci 3:224

Blasiak R, Durussel C, Pittman J, Sénit CA, Petersson M, Yagi N (2017) The role of NGOs in negotiating the use of biodiversity in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction. Mar Policy 81:1–8

Cózar A, Martí E, Duarte CM, García-de-Lomas J, van Sebille E, Ballatore TJ, Eguíluz VM, González-Gordillo JI, Pedrotti ML, Echevarría F, Troublè R, Irigoien X (2017) The Arctic Ocean as a dead end for floating plastics in the North Atlantic branch of the Thermohaline Circulation. Sci Adv 3(4):e1600582

De Lucia V (2017) The Arctic environment and the BBNJ negotiations. Special rules for special circumstances? Mar Policy 86:234–240

De Santo EM (2013) Missing marine protected area (MPA) targets: how the push for quantity over quality undermines sustainability and social justice. J Environ Manag 124:137–146

Druel E, Gjerde KM (2014) Sustaining marine life beyond boundaries: options for an implementing agreement for marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Mar Policy 49:90–97

Druel E et al (2013) Getting to yes? Discussions towards an implementing agreement to UNCLOS on biodiversity in ABNJ

Dunn D et al (n.d.) Deep, distant and dynamic: critical considerations for incorporating the open-ocean into a new BBNJ treaty

Earth Negotiations Bulletin (2017) Ocean conference highlights. http://enb.iisd.org/download/pdf/enb3232e.pdf, IISD Reporting Services. 32

European Commission (2018) Plastic Waste: a European strategy to protect the planet, defend our citizens and empower our industries. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-5_en.htm

FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture department (2016) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture: contributing to food security and nutrition for all. FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5555e.pdf

Freytas-Tamura Kd (2017a) In Kenya, selling or importing plastic bags will cost you $19,000—or jail. The New York TImes. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/28/world/africa/kenya-plastic-bags-ban.html

Freytas-Tamura Kd (2017b) Public shaming and even prison for plastic bag use in Rwanda. The New York Times. https://mobile.nytimes.com/2017/10/28/world/africa/rwanda-plastic-bags-banned.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage

Gourmelon G (2015) Global plastic production rises, recycling lags. New Worldwatch Institute analysis explores trends in global plastic consumption and recycling Recuperado de http://www.worldwatch.org

Harden-Davies H (2018) The next wave of science diplomacy: marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. ICES J Mar Sci 75:426–434

IUCN (2016) 053—increasing marine protected area coverage for effective marine biodiversity conservation. Retrieved 30. January, 2018, from https://portals.iucn.org/congress/motion/053

Kubowicz S and Booth AM (2017) Biodegradability of plastics: challenges and misconceptions. ACS Publications

Law KL (2017) Plastics in the marine environment. Annu Rev Mar Sci 9(1):205–229

Law KL, Thompson RC (2014) Microplastics in the seas. Science 345(6193):144–145

Levy MA (1995) International cooperation to combat acid rain. Green globe yearbook 1995: 59–68

Morrisette, P. M. (1989). The evolution of policy responses to stratospheric ozone depletion. Nat Resour J: 793–820

Mossop J (2018) The relationship between the continental shelf regime and a new international instrument for protecting marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. ICES J Mar Sci 75:444–450

Ndiso J (2017) Nearly 200 nations promise to stop ocean plastic waste. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-environment-un-pollution/nearly-200-nations-promise-to-stop-ocean-plastic-waste-idUSKBN1E02F7

O'Leary BC, Roberts CM (2017) The structuring role of marine life in open ocean habitat: importance to international policy. Front Mar Sci 4:268

Rochman CM, Browne MA, Underwood AJ, van Franeker JA, Thompson RC, Amaral-Zettler LA (2016) The ecological impacts of marine debris: unraveling the demonstrated evidence from what is perceived. Ecology 97(2):302–312

Sherrington C (2016) Plastics in the marine environment. http://www.eunomia.co.uk/reports-tools/plastics-in-the-marine-environment/, Eunomia

Sliggers J et al (2004) Clearing the air: 25 years of the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution, UN

Sundt P et al (2016) Primary microplastic-pollution: measures and reduction potentials in Norway. http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/Documents/publikasjoner/M545/M545.pdf

Thelen K (2003) In: Mahoney J, Rueschemeyer D (eds) How institutions evolve: insights from comparative historical analysis. Comparative historical analysis in the social sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Thelen K (2004) How institutions evolve: the political economy of skills in Germany, Britain, the United States, and Japan. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

UNEP (2017a) Draft resolution on marine litter and microplastics UNEP/EA.3/L.20. United Nations Environment Assembly of the United Nations Environment Programme. https://papersmart.unon.org/resolution/index

UNEP (2017b) UN declares war on ocean plastic https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/press-release/un-declares-war-ocean-plastic

UNEP (2017c) World commits to pollution-free planet at environment summit Press Release. https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/press-release/world-commits-pollution-free-planet-environment-summit

United Nations (2016) Goal 14: conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources. Sustainable development goals: 17 goals to transform our world. from http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/oceans/

United Nations General Assembly (2017). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 24 December 2017. 72/249. http://undocs.org/en/a/res/72/249

Warner R (2012) Oceans beyond boundaries: environmental assessment frameworks. Int J Mar Coastal Law 27(2):481–499

Warner R (2015) Conservation and sustainable use of high-seas biodiversity: steps towards global agreement. Aust J Marit Ocean Affairs 7(3):217–222

Wright SL, Kelly FJ (2017) Plastic and human health: a micro issue? Environ Sci Technol 51(12):6634–6647

Wright SL, Thompson RC, Galloway TS (2013) The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: a review. Environ Pollut 178:483–492

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiller, R., Nyman, E. Ocean plastics and the BBNJ treaty—is plastic frightening enough to insert itself into the BBNJ treaty, or do we need to wait for a treaty of its own?. J Environ Stud Sci 8, 411–415 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-018-0495-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-018-0495-4