Abstract

A polymer composite based on an innovative filler consisting of microscale powder of nanoporous alumina is modeled. The passing-through nanoscale pores in this system—roughly columnar cylindrical, with diameter of the order of 100 nm—are fully penetrated by the resin, which is not bonded to the inner pore walls by any chemical agent. This system, previously assessed by laboratory experiments, is modeled here for the first time, based on a computational multi-scale hierarchical approach. First, microscale representative volume element (RVE) is modeled in two steps using finite element modeling. Then, the macro-scale RVE is characterized, using a combination of micromechanical rules. The elastic response of the composite is simulated to predict its Young’s modulus. This simulation confirms the former experimental results and helps to shed light on the response of the investigated material, which may represent a novel system for use in disparate composite applications. In particular, the nanoporous microfillers composite is compared with a composite material containing the fillers of the same material yet nonporous, bonded to the matrix. It appears that, with respect to this standard concept of three-phase composites, the presence of the nanopores can compensate for the absence of the bonding agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The field of polymer-based composites is ever growing in engineering applications and—as a consequence—in research striving at improving the respective material performances [1,2,3,4,5]. More and more, in a number of applicative areas such as automotive and aerospace, consumer products and marine industry, the demand grows for replacement of traditional metal-based materials by composites, which should provide the same or even better performance with additional advantages: lightweight (turning into lower energy consumption for transportation and decreased greenhouse gas emission), high recyclability, low cost and—in the biomedical area—increased biocompatibility [6]. One means to obtain performant composites with the above properties has often been devised to be the use of porous reinforcing fillers, which has especially been investigated in the field of dental restorative materials [7,8,9,10,11,12]. In the biomedical area, nanoporous-filler-based composites may also become in perspective smart, at least for the functionality of drug release, for, e.g., antibacterial tasks [13,14,15].

Actually, restorative dentistry is one of the major areas of research in polymeric composites, where the used polymer matrices are resins. On average, every 5 years all major dental companies introduce to the market one new dental restorative composites per application line that should present higher performances as compared to the previous generation. This has been happening at least during the past three decades, yet it is difficult to detect really innovative concepts and impressive improvements in the performance of any such materials [16]. The most remarkable advancements seem to have occurred in the much claimed aesthetic quality, which has also been the real reason for banning amalgam. However, this aesthetic quality is a questionable property [17], when also considering that its common description as of natural appearance is often erroneously called biomimesis, while the structure and function of artificial restorative materials are quite different from those of the native tooth materials.

Advancements in dental composites may in principle occur in either of two directions, namely the resin or the filler formulation [16, 18,19,20]. However, as a matter of fact the second one has been dominating in the recent history, even giving the name to the different classes of composites. Particularly, for truly potentially innovating composites, more exotic types of fillers have been introduced recently [21], of which class our proposal of nanoporous fillers may also be considered an example.

In the previous work, a dental restorative resin composite based on nanoporous microfillers of aluminum oxide, obtained from anodic porous alumina (APA), was proposed and demonstrated, exhibiting improved response to aging in wet ambient for the elastic modulus as measured by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) [22]. The novel experimental composite is based on a standard bisGMA-based matrix used for many years in dental restorative composites [19, 23] and an innovative nanoporous microfiller obtained from anodic porous alumina membranes [24, 25] separated from the metallic substrate and ball-milled. The composite is only dual component (resin matrix—inorganic filler), without the presence of bonding agent at their interface [22]. It was shown that the mechanical interlocking of the resin through the pores of the microfillers replaces the bonding agent, and the experimental composite exhibits better aging stability in water for the elastic modulus than standard composites, likely due to the lack of chemical bonding agent degradation after hydrolysis occurring in the wet oral environment. In particular, the diminished degradation in elastic modulus on aging was observed at body temperature and at 1 Hz strain frequency. The strength of adhesion of this innovative composite to dental tissue was also characterized in a subsequent experiment [26], resulting in only little lower performance than the average of current ternary restorative composites. The nanoporous nature of the described composite is also promising for drug loading function, eventually enabling antibacterial or remineralizing capabilities of the material [15, 27, 28].

In this work, in order to support former work and justify the prosecution of investigations in our concept of a nanoporous microfiller dental resin composite, the mechanical response of the investigated material is simulated through a computational multi-scale modeling procedure. The goal of the work is twofold. On the one hand, to confirm and analyze the experimental results obtained so far with our experimental nanoporous microfiller composites. On the other hand, to provide a simple mean of comparison with traditional composites, based on the same components as to both matrix and filler bulk material properties, yet without porous nanostructuring of the fillers, both with and without the presence of a bonding agent.

2 Modeling Procedure

Hierarchical multi-scale modeling is developed for the purpose of this study, where the outputs of a scale are fed into the next scale as input data. First, the mechanical properties of isolated APA are obtained using finite element (FE) modeling and the influence of APA size on the results is studied. Then, the FE model of a microscale RVE containing APA and surrounding polymer is constructed. At this scale, the interaction between APA and polymer is taken into account, while the influence of APA size on the interaction is also investigated. Finally, the random orientation of APA fillers inside resin is modeled at the final scale of macro, where laminate analogy technique is combined with generalized methods of cell for obtaining the Young’s modulus of the investigated material; the later accounts for the distribution of APA fillers in matrix and the former captures their random orientations.

2.1 Properties of Composite Materials and Structure

The parameters of the individual composite components used for the modeling, including both the material properties and the geometrical parameters describing the composite structure, are summarized in Table 1. For the BisGMA-based matrix, we assumed: modulus Em = 3 GPa, density ρm = 1.1 g/cm3, where “m” stands for matrix. For the bulk amorphous hydrated alumina, as supposed to be resulting from anodization, we assumed: modulus Eba = 60 GPa, density ρba = 2.8 g/cm3, where “ba” stands for bulk alumina. For both materials, we assumed a Poisson ratio ν = 0.3. Models of the different-sized APA fillers are shown in Fig. 1a.

2.2 FE Modeling of the Isolated APA Fillers

The APA filler is constrained at one end and an axial displacement is applied on the other end in order to find the longitudinal and transverse moduli. The reaction forces are extracted from the output of FE modeling, and the moduli are calculated using the following equation:

where FR is the summation of reaction forces on the constrained surface and l represents the distance between constrained and deflected surfaces. Δl denotes the applied displacement and A is the area of the deflected surface.

The same boundary conditions are employed on each axis in order to find the APA’s different properties. A presentation of the model and applied boundary conditions are presented in Fig. 2 in both directions. FE modeling is conducted using commercial Abaqus CAE package with the standard/explicit model [29].

Decreasing the size of elements, different models with various mesh densities are constructed and analyzed. The size of the elements is chosen small enough to ensure independency of the results from mesh density.

2.3 Modeling Microscale RVE

In the second step, microscale RVE consisting of pristine APA and surrounding matrix is modeled in a cubic cell (see Fig. 3). The penetration of matrix into the pores is also taken into account and modeled. It is assumed a shear modulus G = 2.50 GPa, and different Poisson's ratios in the different directions (νx = 0.35, νy = νz = 0.26).

When modeling the interaction at the interface between APA fillers and matrix, penalty friction properties using a tangential behavior are applied to the contact surfaces. This option is widely used by researchers in similar contexts, to capture the behavior of this kind of contact surfaces [30,31,32,33]. The friction coefficient is selected between 0.5 and 100 (highest possible amount), as compared to a frictionless interaction, for which it would be set to zero. One end of the model is restricted from any movement and axial displacement is applied to the other end. The effect of this friction coefficient parameter has been evaluated for the case of a 50%wt loading fraction of the fillers (see Sect. 3).

To investigate the effect of different filler sizes and the respective interaction with the matrix on the results, several FE models are constructed. One of these is shown in Fig. 4. The smallest model with an APA filler consisting of seven pores only is chosen among all, for the sake of visibility. Tetrahedral elements were used in a mapped meshing for matrix, and a free mesh was used for the filler. Two types of surface interactions are visible in the representative colored surfaces in the model of Fig. 4: interpore interactions caused by the penetration of the matrix and external interactions at the external surfaces. The size of the model presented in Fig. 4 is much lower than the implemented model, and Fig. 4 is just a schematic presentation of meshing system and friction surfaces. If the actual model was shown, the meshing system and friction surfaces would not be visible at all because of insignificant ratio of pore size to filler size.

For the case of longitudinal and transverse modulus, the same boundary conditions described in Fig. 2 are applied to the RVE instead of isolated APA and Eq. (1) is used. For the Poisson’s ratio, the following equation holds:

where εl and εt represent longitudinal and transverse strains, respectively.

To obtain the shear modulus, a shear deflection is applied to the free end while the other end is fixed and then following equation is used:

where FR represents the total reaction forces on the constrained surface, L is the distance between constrained and deflected surfaces, Δx is the shear deflection magnitude and A is the area of the deflected surface.

2.4 Modeling Composites at Macro-scale

In this step, the macro-scale RVE of the composite is modeled using a combination of micromechanical techniques to estimate the macroscopic Young’s modulus of investigated materials. The effects of filler size distribution and different frictional interactions between constituents have already been modeled. Another parameter affecting the macroscopic mechanical properties of the investigated composite is the random orientation of the fillers in the macro-scale RVE.

Laminate analogy (LA) is the technique of substituting the randomly oriented composites with a quasi-isotropic laminate, as first developed by Halpin and Pagano [34]. In LA, the randomly oriented short-fiber composite can be replaced with a four-layer quasi-isotropic laminate and the properties are interchangeable. This technique has been proven by several studies on the stiffness and strength properties [35, 36].

The generalized method of cells (GMC) has also been developed first by Paley and Aboudi [37]. In GMC, the composite RVE is divided into sub-cells in which the continuity of deflections and tractions are applicable between cells. Among other available averaging methods, the GMC has the advantage of considering mechanical interactions and stress/strain transfer between the sub-cells. The formulation of GMC has been provided briefly in “Appendix A”.

LA, GMC and classical lamination theory (CLT) were used in this step to obtain the overall properties of the investigated composite. The combination of these methods has been successfully used previously by Rafiee and Eskandariyun for predicting mechanical properties of graphene/polymer nanocomposites [38]. In this study, the developed strategy was customized for the purpose of the current research. A quasi-isotropic laminate was considered with lay-up configuration of [0/90/ ± 45]. Each of these angle plies included 12 cells containing pure matrix as an isotropic material and also 13 cells of microscale RVEs (APA and matrix), where APA is oriented along the direction of ply angle. The properties of each ply consisting of 25 blocks were obtained using the GMC method, and then, CLT was used to estimate the overall Young’s modulus of investigated material. A schematic presentation of the mentioned approach is presented in Fig. 5.

The modeling steps can be briefly outlined as three stages: (i) The modeling starts with extracting the effective modulus of isolate APA filler and analyzing the influence of geometrical parameters; (ii) the interaction between APA and resin is modeled through FE analysis of microscale RVE; (iii) LA is combined with GMC for capturing random orientation and also distribution of APA fillers.

3 Results

3.1 FE Modeling of the Isolated APA filler

As a first step in the model, the pristine APA nanoporous microfiller is designed and analyzed using FE, in order to obtain its equivalent elastic modulus, as compared to the bulk alumina fillers with similar external size. The properties of the starting filler and resin materials are summarized in Table 1 (Experimental section). It was assumed that the size distribution of the APA fillers be Gaussian, with mean diameter of 5 µm and standard deviation of 3 µm. Since such a distribution would show a tail on the short size hand side that would extend down to negative values, which is unphysical, this tail has been cutoff, resulting in the distribution profile shown in Fig. 1b. In Fig. 1a some fillers within this distribution range are shown, which allows one to see the approximate number of pores present inside the typical single filler object.

After single filler modeling, analyses of the same have been done using FE. According to the directions defined in Fig. 2a, for symmetry reasons the filler has the same behavior in directions y and z, perpendicular to the pores. Therefore, the respective elastic modulus is expected to be the same: Efy = Efz, where f apex means single filler value. The elastic modulus resulting in the two independent directions for fillers of some different size is reported in Table 2 and plot in Fig. 6.

It can be seen that there is no major difference in Young’s modulus for the different APA sizes. From Fig. 6, it appears that both moduli undergo the largest change in value for the smallest considered APA filler size of 1 µm diameter. Obviously, on this scale only few pores (just two or three) are span in each transversal direction (meaning that only between four and nine are included in the whole filler), and the boundary effects become quite relevant. Nevertheless, as shown by the average modulus profile, the deviations in the different directions tend to compensate. Anyway, for fillers larger than ~ 5 µm, both the longitudinal and transverse moduli roughly converge, to ~ 43.0 GPa and ~ 35.0 GPa, respectively.

3.2 FE Modeling of the Composite

3.2.1 Microscale RVE

The effect of friction coefficient between APA filler walls and fully pore penetrating resin, as variable in the chose range ([0.5, 100]), has been calculated and is shown hereafter in Fig. 7.

Obviously, while for low friction coefficients (approximately below 5), there is a clear deviation toward lower values of the modulus, above 5 the modulus tends asymptotically to a stable value of ~ 9.3 GPa. In any case, even the lowest value (~ 8.62 GPa) does not present a major deviation from the asymptotic value (~ − 7%).

Since no major difference is seen on the final results, thus the results of the model with mild friction coefficient value of 0.5 were considered next and are presented in Table 3. Due to the transversely isotropic behavior of the RVE, five engineering constants are reported, which are defined as follows: E1 is the longitudinal elastic modulus, whereas E2 = E3 are the transversal ones; similarly, ν1 and ν2 = ν3 are the longitudinal and transversal Poisson ratios, respectively; G is the shear modulus.

It should be noticed that the observed differences for the Young’s modulus in the two independent directions are roughly in line with those appearing formerly for the single filler case.

These results were obtained for the case of aligned APA fillers in the composite. Hence, for a realistic model of the composite, where the APA fillers are oriented randomly at all directions in space, the longitudinal modulus mentioned above will be an upper-bound limit.

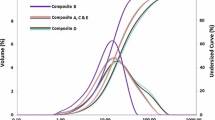

3.3 Macro-scale Composite

Using the LA-GMC approach implemented as described in the experimental section, we obtained the macro-scale modulus of the composite with randomly oriented APA fillers. The results for different weight loading fractions are reported in Table 4 and plotted in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 shows that, for a loading fraction of 50%wt, the modulus of the APA composite should fall between ~ 5 and ~ 9 GPa. Actually, previous measurements of the same experimental APA-based composite by means of DMA [22] reported values of storage modulus around 5.2 GPa, so within the range found here, yet closer to the lower limit.

In Fig. 8, the macro-scale results represent the lower bound, and they are compared with the microscale RVE results, which represent the upper bound (case of aligned APA fillers). Along with these two results, the rule of mixture (ROM) estimation is also presented, which has been calculated by using the pristine APA filler modulus. The modulus of the investigated composites with any APA weight fraction is bounded between the lower and upper limits.

For the case of 50%wt loading only, the modeling was repeated for the control material with which the present concept of composite has to be compared with, namely the composite made with same materials but nonporous and yet bonded filler. The resulting modulus is found to be 5.13 GPa, which corresponds to the red circular spot in Fig. 8. While higher than the 50%wt result for the APA-based composite object of the present work, which is found to be 4.89 GPa, this value is not significantly different. Obviously, the APA filler porosity can compensate for most of the action of the bonding agent present in the traditional nonporous and bonded alumina composite.

4 Discussion

The values of the mechanical properties of the single composite components are probably affected by a rather large uncertainty. This holds especially true for the elastic modulus, and particularly for the filler bulk material. In fact, in the literature, Xia et al. [39] reported an elastic modulus of bulk alumina as high as 140 GPa, whereas Fang et al. [40] reported the quite low value of 5 GPa, when including the porosity as in APA. Ko et al. [41], in turn, reported variable values between 70 and 140 GPa. Here, considering that the alumina resulting from anodization is both mainly amorphous and is additionally hydrated (with water contents around 5%wt [need ref]), we assumed Eba = 60 GPa. However, the uncertainty could be quite high, probably up to ± 50%. For the resin modulus, the uncertainty is probably much lower, around ± 15%. In some respect, BisGMA can be thought to be similar to an epoxy, with a typical modulus of ~ 2 GPa. However, the actual formulation of the matrix containing BisGMA usually includes some additional comonomers, to make the paste less thick and viscous, such that it can be actually mixed with the filler powder. In fact, Emami et al. [42] reported, for pure BisGMA, a modulus of 4.15 GPa, whereas for pure TEGDMA, a value of 2.37 GPa. We also used TEGDMA as a comonomer, in the wt ratio of 70:30 BisGMA-TEGDMA, which, according to the rules of mixtures, could correspond to an upper limit (weighted mean) of 3.6 GPa. To be conservative, we assumed thus a matrix modulus of 3 GPa. It should also be considered that this additionally depends on the actual degree of conversion reached on photopolymerization [43, 44].

It should be reminded here that the APA filler of the experimental composite is not bonded to the matrix, and the only “bonding” present at the interface between the two phases is a friction coefficient assigned to them for the relative displacement of one with respect to another. This has been selected as described in the experimental section. Whereas the upper limit of friction coefficient range considered in the study presented in Fig. 7 may seem unrealistically high, nevertheless we observed that the deviations found in Young’s modulus for the highest friction coefficients were only limited (+ 7.5%), and thus we finally assumed a moderate value of 0.5.

In the step from microscale RVE to macro-scale modeling, the random orientation of the APA fillers is introduced. As one possible limitation of our model, it is worth mentioning that the agglomeration of APA fillers is not considered, since APA fillers were very well dispersed in the production process in this study. Therefore, fully dispersed situation is modeled.

It has been stated that the experimental value of 5.2 GPa found previously for the storage modulus of the APA composite for 50%wt loading could probably be increased by further improvement in the mixing process, or by implementing a mixed strategy, also including a bonding agent in support of the resin-filled pores in the filler. This could hopefully result into a modulus of up to 8–10 GPa [22]. The improved filler-matrix mixing, in particular, could reduce the formations of filler agglomerates and thus improve the bonding. This issue affects the modulus similar to the alignment of fillers. Hence, the presented possible area (green area) in Fig. 8 could be reliable even using different experimental parameters. It should be pointed out that currently developed hierarchical modeling very well serves the purpose of this study, since it was intended to predict the modulus. Stochastic or concurrent model might be required to be utilized for more complicated problems like characterizing the fracture behavior [45,46,47].

5 Conclusion

Previous experiments showed that the modulus of the experimental APA-based composite is not affected significantly by the aging. Therefore, even if still a bit lower than that of traditional (three phases, bonded-fillers) composites, this composite shows the advantage of being more stable over the time. In this work we modeled the material, through the following key stages: (i) modeling isolated APA and studying the influence of geometrical parameters on the results; (ii) modeling the interaction between APA and surrounding polymer through FE analysis as microscale modeling; (iii) combining laminate analogy of generalized method of cell; this is the most important contribution of the current work, which has not been done before. The modeling results presented here supported the statement about an equivalent modulus of the considered composite as that of traditional composites, yet obtained by means of the mechanical interlocking of the resin in the filler nanopores. This is a promising result, in view of the possible advantages of avoiding the bonding agent phase, which may be labile on aging in harsh conditions such as high temperature or penetrating liquids, and of having the inherent capability of the filler pores as carrier for release of active agents into the bulk material, particularly for biomedical applications. In perspective, it will be worth investigating the strain mechanism of the porous filler frame, to check if its elasticity can allow for partial relaxation of stress during deformation, and to model the volumetric shrinkage of the resin, to assess if this could also take advantage of the porous volume reservoir, in case of, apparently defective, incomplete pore filling.

Availability of data and material

The data can be made available, on request.

Abbreviations

- RVE::

-

Representative volume element

- APA::

-

Anodic porous alumina

- DMA::

-

Dynamic mechanical analysis

- FE::

-

Finite element

- LA::

-

Laminate analogy

- GMC::

-

Generalized method of cells

- CLT::

-

Classical lamination theory

- ROM::

-

Rule of mixture

References

Mittal, G.; Rhee, K.Y.; Mišković-Stanković, V.; Hui, D.: Reinforcements in multi-scale polymer composites: processing, properties, and applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 138, 122–139 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.11.028

Dikshit, V.: Multiscale polymer composites: a review of the interlaminar fracture toughness improvement. Fibers (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/fib5040038

Sadasivuni, K.K.; Saha, P.; Adhikari, J.; Deshmukh, K.; Ahamed, M.B.; Cabibihan, J.-J.: Recent advances in mechanical properties of biopolymer composites: a review. Polym. Compos. 41, 32–59 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.25356

Patterson, B.A.; Malakooti, M.H.; Lin, J.; Okorom, A.; Sodano, H.A.: Aramid nanofibers for multiscale fiber reinforcement of polymer composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 161, 92–99 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2018.04.005

Zagho, M.M.; Hussein, E.A.; Elzatahry, A.A.: Recent overviews in functional polymer composites for biomedical applications. Polymers (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10070739

Lederman, M.; Sharon, E.; Lipovezky-Adler, M.; Smidt, A.: Biocompatibility of composites–literature review. Refuat. Hapeh. Vehashinayim. 32, 21–29 (2015)

Bowen, R.L.; Reed, L.E.: Semiporous reinforcing fillers for composite resins: I. Preparation of provisional glass formulations. J. Dent. Res. 55, 738–747 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345760550050701

Samuel, S.P.; Li, S.; Mukherjee, I.; Guo, Y.; Patel, A.C.; Baran, G.; Wei, Y.: Mechanical properties of experimental dental composites containing a combination of mesoporous and nonporous spherical silica as fillers. Dent. Mater. 25, 296–301 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2008.07.012

Liu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Lei, T.; Xiang, Q.; Han, Y.; Huang, B.: Effect of porous glass-ceramic fillers on mechanical properties of light-cured dental resin composites. Dent. Mater. 25, 709–715 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2008.10.013

Zandinejad, A.A.; Atai, M.; Pahlevan, A.: The effect of ceramic and porous fillers on the mechanical properties of experimental dental composites. Dent. Mater. 22, 382–387 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2005.04.027

Brostow, W.; Estevez, M.; Lobland, H.E.H.; Hoang, L.; Rodriguez, J.R.; Vargar, S.: Porous hydroxyapatite-based obturation materials for dentistry. J. Mater. Res. 23, 1587–1596 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.2008.0191

Atai, M.; Pahlavan, A.; Moin, N.: Nano-porous thermally sintered nano silica as novel fillers for dental composites. Dent. Mater. 28, 133–145 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2011.10.015

Loca, D.; Locs, J.; Dubnika, A.; Zalite, V.; Berzina-Cimdina, L.: 9—porous hydroxyapatite for drug delivery. In: Mucalo, M. (ed.) Hydroxyapatite (Hap) for Biomedical Applications. pp. 189–209. Woodhead Publishing (2015)

Gunathilake, T.M.S.U.; Ching, Y.C.; Ching, K.Y.; Chuah, C.H.: Biomedical and microbiological applications of bio-based porous materials : a review. MDPI Polym. 9, 160–175 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9050160

Thorat, S.; Diaspro, A.; Scarpellini, A.; Povia, M.; Salerno, M.: Comparative study of loading of anodic porous alumina with silver nanoparticles using different methods. Materials (Basel). 6, 206–216 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6010206

Darvell, B.: Innovation in restorative dental materials: another new age or the end of the line? Future Med. Chem. 5, 1595–1597 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4155/fmc.13.131

Darvell, B.W.: Esthetic dentistry. Am. J. Esthet. Dent. 3, 167–168 (2013)

Chen, M.-H.: Update on dental nanocomposites. J. Dent. Res. 89, 549–560 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510363765

Ferracane, J.L.: Resin composite–state of the art. Dent. Mater. 27, 29–38 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.020

Ferracane, J.L.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Hilton, T.J.: Microstructural features of current resin composite materials. Curr. Oral Heal. Rep. 1, 205–212 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40496-014-0029-4

Habib, E., Wang, R., Wang, Y., Zhu, M., Zhu, X.X.: Inorganic Fillers for Dental Resin Composites: Present and Future. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5b00401 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00401

Thorat, S.B.; Diaspro, A.; Salerno, M.: In vitro investigation of coupling-agent-free dental restorative composite based on nano-porous alumina fillers. J. Dent. 42, 279–286 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2013.12.001

Darvell, B.W.: Materials Science for Dentistry. Woodhead Publishing (2009)

Sulka, G.D.: Highly ordered anodic porous alumina formation by self-organized anodizing. In: Eftekhari, A. (Ed.) Nanostructured Materials in Electrochemistry, pp. 1–96. Wiley, New York (2008)

Salerno, M.; Patra, N.; Losso, R.; Cingolani, R.: Increased growth rate of anodic porous alumina by use of ionic liquid as electrolyte additive. Mater. Lett. 63, 1826–1829 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2009.05.058

Salerno, M.; Loria, P.; Matarazzo, G.; Tomè, F.; Diaspro, A.; Eggenhöffner, R.: Surface morphology and tooth adhesion of a novel nanostructured dental restorative composite. Materials (Basel). 9, 203–210 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9030203

Salerno, M.; Giacomelli, L.; Larosa, C.: Biomaterials for the programming of cell growth in oral tissues : the possible role of APA bioinformation. Bioinformation 5, 291–293 (2010)

Toccafondi, C., Dante, S., Reverberi, A.P., Salerno, M.: Biomedical applications of anodic porous alumina. Curr. Nanosci. 11 (2015)

Smith, M.: ABAQUS Standard Users’ Manual, Version 6.9. (2009)

Schmidt, H.; Hattel, J.: A local model for the thermomechanical conditions in friction stir welding. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 13, 77–93 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/13/1/006

Shi, J.; Chopp, D.; Lua, J.; Sukumar, N.; Belytschko, T.: Abaqus implementation of extended finite element method using a level set representation for three-dimensional fatigue crack growth and life predictions. Eng. Fract. Mech. 77, 2840–2863 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2010.06.009

Huang, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.: Numerical simulation of steel-laminated bearing considering friction slipping. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 10, 162–166 (2018). https://doi.org/10.7763/IJET.2018.V10.1052

Jin, X.: Stress analysis of cold rolled steel sheet based on abaqus. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 10, 5–8 (2019)

Halpin, J.C.; Pagano, N.J.: The laminate approximation for randomly oriented fibrous composites. J. Compos. Mater. 3, 720–724 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1177/002199836900300416

Li, Y.; Pimenta, S.: Development and assessment of modelling strategies to predict failure in tow-based discontinuous composites. Compos. Struct. 209, 1005–1021 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.05.128

Feraboli, P.; Cleveland, T.; Stickler, P.; Halpin, J.: Stochastic laminate analogy for simulating the variability in modulus of discontinuous composite materials. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 41, 557–570 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.01.003

Paley, M.; Aboudi, J.: Micromechanical analysis of composites by the generalized cells model. Mech. Mater. 14, 127–139 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6636(92)90010-B

Rafiee, R.; Eskandariyun, A.: Predicting Young’s modulus of agglomerated graphene/polymer using multi-scale modeling. Compos. Struct. 245, 112324 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112324

Xia, Z.; Riester, L.; Sheldon, B.W.; Curtin, W.A.; Liang, J.; Yin, A.; Xu, J.M.: Mechanical properties of highly ordered nanoporous anodic alumina membranes. 6 (2004)

Tong, T.F.; Wang, H.; Kang, L.J..S.: Physical behavior of nanoporous anodic alumina using nanoindentation and microhardness tests. 410–415 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-007-9076-2

Ko, S.H.; Lee, D.W.; Jee, S.E.; Park, H.C.; Lee, K.H.; Hwang, W.: Mechanical properties and residual stress measurements in anodic aluminium oxide structures using nanoindentation. Glas. Phys. Chem. 31, 356–363 (2005)

Emami, N.; Kj, S.: Young’s modulus and degree of conversion of different combination of light-cure dental resins. 202–207 (2009)

Thorat, S.; Patra, N.; Ruffilli, R.; Diaspro, A.; Salerno, M.: Preparation and characterization of a BisGMA-resin dental restorative composites with glass, silica and titania fillers. Dent. Mater. J. 31, 635–644 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4012/dmj.2011-251

Thorat, S.; Diaspro, A.; Salerno, M.: Effect of alumina reinforcing fillers in BisGMA-based resin composites for dental applications. Adv. Mater. Lett. 4, 15–21 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5185/amlett.2013.icnano.283

Hamdia, K.M.; Silani, M.; Rabczuk, T.: Stochastic analysis of the fracture toughness of polymeric nanoparticle composites using polynomial chaos expansions. Int. J. Fracture 206, 215–227 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10704-017-0210-6

Msekh, M.A.; Cuong, N.H.; Zi, G.; Areias, P.; Zhuang, X.; Rabczuk, T.: Fracture properties prediction of clay/epoxy nanocomposites with interphase zones using a phase field model. Eng. Frac. Mech. 188, 287–299 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2017.08.002

Talebi, H.; Silani, M.; Rabczuk, T.: Concurrent multiscale modeling of three dimensional crack and dislocation propagation. Adv. Eng. Soft. 80, 82–92 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2014.09.016

Funding

Open access funding provided by Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The research was supported by the institutional fund of the COMRESLAB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR and MS contributed to conceptualization and Supervision; RR and AE contributed to methodology; AE contributed to formal analysis and investigation; MS contributed to writing—original draft preparation; RR, AE and CL contributed to writing—review and editing; RR contributed to funding acquisition and resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix A: GMC

Appendix A: GMC

The GMC is a micromechanical technique developed by Paley and Aboudi to model a multiphase composite consisting of repetitive unit-cells. The GMC presents a generalization of the method of cells, which was previously designed only to model a four-cell network, to an arbitrary number of cells. This micromechanical technique, uses the continuity of displacement and traction rates at the interfaces. The developed homogenization, will results in an effective imitation of the composite’s behavior [36].

From the continuity of displacements, we have:

Equations A1 to A3 can be replaced in matrix form as:

Similarly, for the continuity of tractions we have:

It can be obtained from equation A4 and A7:

εs can be extracted from Eq. A8 as:

The average strains to local stresses can be related using stiffness matrices as:

The final stiffness matrix will be obtained as [36]:

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rafiee, R., Eskandariyun, A., Larosa, C. et al. Multi-scale Modeling of Polymeric Composites Including Nanoporous Fillers of Milled Anodic Alumina. Arab J Sci Eng 47, 8189–8198 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-06199-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-06199-x