Abstract

Peripheral nerve injury downregulates the expression of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) and voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.2 by increasing their DNA methylation in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG). Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 (TET1) causes DNA demethylation. Given that DRG MOR and Kv1.2 downregulation contribute to neuropathic pain genesis, this study investigated the effect of DRG TET1 overexpression on neuropathic pain. Overexpression of TET1 in the DRG through microinjection of herpes simplex virus expressing full-length TET1 mRNA into the injured rat DRG significantly alleviated the fifth lumbar spinal nerve ligation (SNL)–induced pain hypersensitivities during the development and maintenance periods, without altering acute pain or locomotor function. This microinjection also restored morphine analgesia and attenuated morphine analgesic tolerance development after SNL. Mechanistically, TET1 microinjection rescued the expression of MOR and Kv1.2 by reducing the level of 5-methylcytosine and increasing the level of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the promoter and 5′ untranslated regions of the Oprml1 gene (encoding MOR) and in the promoter region of the Kcna2 gene (encoding Kv1.2) in the DRG ipsilateral to SNL. These findings suggest that DRG TET1 overexpression mitigated neuropathic pain likely through rescue of MOR and Kv1.2 expression in the ipsilateral DRG. Virus-mediated DRG delivery of TET1 may open a new avenue for neuropathic pain management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 7% of the world’s population suffers from neuropathic pain in their lifetime [1]. Although there are multiple drugs for the treatment of this disorder, opioids remain the last option of prescribed management for moderate to severe neuropathic pain. However, most of neuropathic pain patients require high doses of opioids as well as repeated and prolonged administration of opioids to alleviate pain. The side effects of opioids significantly limit their use in neuropathic pain patients. Increasing evidence demonstrated that unsatisfactory pain relief under neuropathic pain conditions may result, at least in part, from nerve injury–induced changes in gene transcription and translation of receptors (e.g., opioid receptor downregulation), voltage-dependent channels (e.g., voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.2 downregulation), and enzymes in the first-order sensory neurons of the ipsilateral dorsal root ganglion (DRG) [2, 3]. Therefore, targeting the molecules and/or pathways that participate in nerve injury–induced changes of DRG gene expression may open a new avenue for treatment of neuropathic pain.

Epigenetic modification, such as DNA methylation, is a key mechanism for gene regulation [4]. DNA methylation represses gene transcription through several mechanisms, including serving as a docking site for transcription repressors/corepressors, such as the family of methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins [4, 5]. DNA methylation is catalyzed primarily by members of the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) family, including DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b [4], whereas ten-eleven translocation (TET) methylcytosine dioxygenases (TETs including TET1–3) mediate the conversion of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), hence promoting DNA demethylation [6].

Our recent studies showed that DNMT3a-triggered epigenetic silencing of Oprm1 (encoding μ-opioid receptor (MOR)) and Kcna2 (encoding Kv1.2) genes in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury contributes to neuropathic pain development. MOR downregulation in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury enhances the release of primary afferent neurotransmitters after peripheral nerve injury [7, 8]. MOR knockout mice exhibited increased mechanical pain hypersensitivity under neuropathic pain conditions [9]. This evidence suggests that nerve injury–induced MOR downregulation in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury may participate in mechanisms of neuropathic pain through a loss of tonic MOR-mediated inhibition at the central terminals of the primary afferents [7, 8, 10, 11]. In addition, nerve injury–induced Kv1.2 downregulation in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury participates in neuropathic pain genesis, as evidenced by the fact that this downregulation produced DRG neuronal hyperexcitability and that rescuing this downregulation attenuated nerve injury–induced pain hypersensitivity [12, 13]. Further studies revealed that peripheral nerve injury increased the expression of DNMT3a (but not DNMT3b) without altering the expression of TET1–3 in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury [14]. This increase contributed to nerve injury–induced downregulation of MOR and Kv1.2 through elevation of DNA methylation in their gene promoter regions in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury [8, 14]. Thus, blocking nerve injury–induced increase of DNA methylation in DRG Oprm1 and Kcna2 gene promoters may have an antinociceptive effect under neuropathic pain conditions.

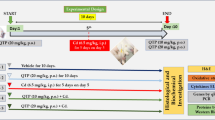

TET1, one of the TET family of proteins (TET1–3), catalyzes the oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC by direct enzymatic removal of the 5-hydroxylated methyl group and replacement of the methylated cytosine base via DNA base excision repair pathway, resulting in DNA demethylation and gene expression induction [15]. In this study, we constructed herpes simplex virus (HSV) expressing full-length rat TET1 (HSV-TET1). We first observed whether DRG TET1 overexpression, through the microinjection of HSV-TET1 into the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury, affected the fifth lumbar (L5) spinal nerve ligation (SNL)–induced neuropathic pain in Sprague-Dawley rats, a well-established and characterized preclinical rat model that mimics trauma-induced neuropathic pain in the clinic. Then, we examined whether this microinjection improved morphine analgesia and prevented morphine analgesic tolerance under SNL-induced neuropathic pain conditions. Finally, we unveiled the mechanisms of how DRG TET1 overexpression produced these effects.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (8–10 weeks) weighing 250 to 300 g, purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc., USA, were used. Rats were housed in a standard 12-h light/dark cycle at 20–25 °C and 60% humidity, with water and food pellets available ad libitum in specific-pathogen-free cages. Before the experiments, all the animals were allowed to habituate to the animal facility for at least 3 days. All procedures used were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School (Newark, New Jersey) and consistent with the ethical guidelines of the US National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain. The experimenters were blind to viral treatment or drug treatment condition. All rats were finally euthanized with overdose of isoflurane for tissue collection.

Neuropathic Pain Model

SNL model of neuropathic pain in rats was carried out according to previously published methods with minor modification [8, 13, 16]. In brief, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane, and adequate anesthesia was ascertained by the lack of a withdrawal response to a nociceptive stimulus. After an incision on the lower back was made, the L5 spinal nerve was exposed and isolated from the adjacent nerves carefully. The L5 spinal nerve was then tightly ligated with 3–0 silk thread and transacted distal to the ligature. In sham-operated groups, the L5 spinal nerve was isolated, but was neither ligated nor transacted. The surgical field was irrigated with sterile saline, and the skin incision was closed with wound clips. Only rats without any abnormality (e.g., normal activity and body weight, normal gait, and no wound infection) were included in this study.

DRG Microinjection

DRG microinjection was carried out as described in detail in our previous publications [8, 13, 17, 18]. Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and adequate anesthesia was ascertained as described above. A midline incision was made in the lower lumbar back region. After the unilateral L5 DRG was exposed, the virus (1–1.5 μl; 3–5 × 108 units/ml) or phosphate buffer saline (PBS; 1–1.5 μl) was injected into the DRG through a glass micropipette (tip diameter, 20 to 40 μm) that was connected to a Hamilton syringe. The pipette was kept in place for 10 min after injection. The surgical field was irrigated with sterile saline, and the skin incision was closed with wound clips.

Behavioral Tests

Thermal test was carried out as previously described [7, 19]. Briefly, paw withdrawal latencies to noxious heat were measured with Model 336 Analgesia Meter (IITC Inc./Life Science Instruments, USA). A beam of light that provided radiant heat was aimed at the middle of the plantar surface of each hind paw. When the animal lifted its foot, the light beam turned off. Paw withdrawal latency was defined as the number of seconds between the start of the light beam and the foot response. The cut-off time was 20 s to avoid tissue damage. Each trial was repeated 5 times at 5-min intervals for each side.

Mechanical test was performed as described [7, 19]. Briefly, paw withdrawal thresholds in response to mechanical stimuli were measured with the up–down testing paradigm. The rats were placed in an individual Plexiglas chamber on an elevated mesh screen. Von Frey filaments in log increments of force (0.69, 1.20, 2.04, 3.63, 5.50, 8.51, 15.14, and 26 g) were applied to the plantar surface of the rats’ left and right hind paws. The 3.63-g stimulus was applied first. If a positive response occurred, the next smaller von Frey hair was used; if a negative response was observed, the next larger von Frey hair was used. The test was terminated when i) a negative response was obtained with the 26-g hair or ii) 3 stimuli were applied after the first positive response. Paw withdrawal latency was determined by converting the pattern of positive and negative responses to the von Frey filament stimulation to a 50% threshold value based on a formula provided by Dixon [20].

The locomotor function test was carried out according to the methods described previously [21]. The following tests were performed before tissue collection or rat euthanization: 1) placing reflex—the rat was held with the hind limbs slightly lower than the forelimbs, and the dorsal surfaces of the hind paws were brought into contact with the edge of a table. The experimenter recorded whether the hind paws were placed on the table surface reflexively; 2) grasping reflex—the rat was placed on a wire grid, and the experimenter recorded whether the hind paws grasped the wire on contact; 3) righting reflex—the rat was placed on its back on a flat surface, and the experimenter noted whether it immediately assumed the normal upright position. Scores for placing, grasping, and righting reflexes were based on counts of each normal reflex exhibited in 5 trials.

DRG Neuronal Culture and Transfection

Briefly, 3–4-week-old rats were euthanized with isoflurane. The DRG was collected in cold Neurobasal Medium (Gibco/ThermoFisher Scientific) that contained 10% fetal bovine serum (JR Scientific, Woodland, CA), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD). The DRG was then treated with enzyme solution (5 mg/ml dispase, 1 mg/ml collagenase type I in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Gibco/ThermoFisher Scientific). After trituration and centrifugation, dissociated cells were resuspended in mixed Neurobasal Medium and plated in a 6-well plate coated with 50 mg/ml poly-d-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. One day later, 0.5 μl of each virus (titer 5 × 1012/ml) was added to each 2-ml well. Neurons were collected 2 to 3 days later.

Western Blotting Analysis

Unilateral L5 DRGs of 2 rats were pooled together to obtain enough proteins. The tissues were homogenized in chilled lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 40 μM leupeptin, and 250 mM sucrose). After centrifugation at 4 °C for 15 min at 1000g, the supernatant was collected for cytosolic proteins, and the pellet was collected for nuclear proteins. The protein concentration in the samples was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad). Then, the samples (20 μg/sample) were heated at 99 °C for 5 min and loaded onto a 4 to 15% stacking/7.5% separating sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). According to molecular weight sizes of target proteins and housekeepers, the membrane was cut into different pieces. After being blocked with 3% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h, each piece of the membrane was incubated with the following primary antibodies, respectively, overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used include rabbit anti-TET1 (1:1000, Abcam), mouse anti-Kv1.2 (1:1000, NeuroMab), rabbit anti-histone H3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-phosphorylated extracellular signal–regulated kinase (p-ERK1/2, 1:1000; Cell Signaling), goat anti-Nav1.9 (1:200; Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-S6K (1:1000, Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-TET2 (1:3000, EMD Millipore), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:1000, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:1000; Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-MOR (1:500, Immunostar, USA), and rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:1000; Santa Cruz). The selectivity of the anti-MOR or anti-Kv1.2 was characterized in our previous work [22] or by the vendor. The proteins were detected by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, or anti-goat secondary antibody (1:3000, Jackson ImmunoResearch), visualized by western peroxide reagent and luminol/enhancer reagent (Clarity Western ECL Substrate, Bio-Rad), and exposed by the ChemiDoc XRS System with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). The intensity of the blots was quantified with densitometry using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). Based on our previous studies [13, 14, 23, 24], the AAV-GFP-microinjected sham group showed no changes of targeting protein expression in the DRG. Therefore, the expression level in the DRG from this group is considered basal expression and set as 100%. The relative density values from the remaining treated groups were determined by dividing the optical density values from these groups by the value of the AAV-GFP-microinjected sham group after each was normalized to the corresponding housekeeper protein density (normalized to either α-tubulin or GAPDH for cytosol proteins or to total histone H3 for nucleus proteins).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde before being analyzed by single- or double-labeled immunohistochemistry. L4/5 DRGs, L5 spinal cord, L5 spinal nerve, L5 dorsal root, and brain were removed, post-fixed, and dehydrated before frozen sectioning at 20 μm. After the sections were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 0.01 M PBS containing 10% goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100, they were incubated with chicken anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP, 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) alone or with a mixture of chicken anti-GFP plus mouse anti-neurofilament-200 (NF200, 1:500, Sigma), biotinylated isolectin B4 (IB4, 1:100, Sigma), mouse anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP, 1:50, Abcam), rabbit anti-MOR (1:500, Neuromics), or mouse anti-glutamine synthetase (GS, 1:500, EMD Millipore) overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with goat anti-chicken antibody conjugated to Cy2 (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) alone or with a mixture of goat anti-chicken antibody conjugated to Cy2 or Cy3 (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) plus donkey anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Cy3 (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or avidin labeled with Cy2 (1:200, Life Technologies) for 2 h at room temperature. Control experiments included substitution of normal mouse or chicken serum for the primary antiserum and omission of the primary antiserum. All immunofluorescence-labeled images were examined using a Leica DMI4000 fluorescence microscope and captured with a DFC365FX camera (Leica, Germany).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Genomic DNA was extracted from DRG using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then sonicated to 100–500-bp fragments. Immunoprecipitation for 5hmC was performed using Thermo Scientific EpiJET 5hmC Enrichment Kit (Thermo Scientific) [25]. Briefly, 5hmC in 500 ng fragmented genomic DNA was modified by the linker via modification enzyme. After purification, 40 μl DNA with 5hmC linker was chemically modified by biotin moiety using 50 μl biotin reagent at 50 °C for 5 min, and then mixed with 20 μl streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and 40 μl streptavidin binding buffer. Finally, DNA with 5hmC was separated from beads after washing and incubated at 70 °C for 5 min. Immunoprecipitation for 5mC was carried out using the Methylated-DNA Immunoprecipitation Kit (D5101, Zymo Research) [26]. Briefly, 160 ng fragmented DNA in 50 μl DNA denaturing buffer was denatured at 98 °C for 5 min. The 250 μl MIP buffer containing 15 μl of ZymoMag Protein A and 1.6 μl mouse anti-5-methylcytosine was added at 37 °C for 1 h on a rotator. After the beads were suspended with 500 μl MIP buffer, DNA was precipitated and resuspended in 200 μl of water for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis as described below. The no enzyme group in the reaction was used as a negative control. The equal genomic DNA was used as input control.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Briefly, the bilateral L5 DRGs of rats were collected in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) and subjected to total RNA extraction using the miRNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA then was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) and oligo (dT) primers. The cDNA (1 μl), the immunoprecipitated DNAs (4 μl) from the treated groups above, or the DNA (4 μl) from the inputs (used as the reference controls) of the corresponding treated groups was amplified by real-time PCR using the primers listed in Table 1. Each sample was run in triplicate in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 250 nM forward and reverse primers, 10 μl of SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and 20 ng of cDNA. The PCR amplification consisted of an initial 1-min incubation at 95 °C, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. Ratios of the remaining treated groups to the PBS plus sham group or ratios of ipsilateral-side mRNA levels to contralateral-side mRNA levels were calculated using the ΔCt method (2−ΔΔCt).

Single-cell real-time RT-PCR was performed as described previously [14]. Briefly, the freshly cultured DRG neurons were prepared as described before [14]. Four hours after plating, under an inverted microscope fit with a micromanipulator and microinjector, a single living large (> 35 μm), medium (25–35 μm), and small (< 25 μm) DRG neuron was harvested in a PCR tube with 10 μl of cell lysis buffer (Signosis, Sunnyvale, CA). After centrifugation, the supernatants were collected and divided into 3 PCR tubes for Gif, Oprm1, and Gapdh mRNAs. The remaining real-time RT-PCR procedure was performed based on the manufacturer’s instructions with the single-cell real-time RT-PCR assay kit (Signosis). All primers used are listed in Table 1, and 40 PCR cycles were run.

Plasmid Constructs and Virus Production

Two segments of rat Tet1 coding sequences were amplified separately from total RNA of rat DRG using the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System with the Platinum Taq High Fidelity Kit (Invitrogen) and the primers (Table 1). After nested PCR of each product using Platinum Pfx DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) and the primers (Table 1) respectively, the PCR products were inserted into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and validated by sequencing. Two plasmids harboring each end of the coding sequences of rat Tet1 were combined into 1 plasmid using KpnI and AscI restriction sites to get the full-length TET1 plasmid. The resulting vector was submitted to Viral Gene Transfer Core at MIT for the LR recombination reaction and HSV p1005 package. The HSV-GFP used as a control was provided by Dr. Eric J Nestler (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York). AAV5-DNMT3a (that expresses rat full-length DNMT3a) and AAV5-GFP were packaged as described before [14].

Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as means ± SEM. The data from the behavioral tests, RT-PCR, and Western blot were statistically analyzed with 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When ANOVA showed a significant difference, pairwise comparisons between means were tested by the post hoc Tukey method. The data were analyzed by SigmaPlot 12.5 (USA). All probability values were 2 tailed and significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

The Microinjected HSV Is Limited to the Ipsilateral DRG Neurons and Their Fibers

Before the effect of DRG viral microinjection on behavioral responses was examined, we first observed the distribution of HSV in the DRG and spinal cord after microinjection of HSV-GFP into unilateral L5 DRG. GFP-labeled HSV was detected in the ipsilateral L5 DRG neurons (Fig. 1A), ipsilateral L5 spinal nerve (Fig. 1B), and ipsilateral L5 dorsal root (data not shown). GFP-labeled HSV was not distributed in the ipsilateral L5 DRG GS (a marker for satellite cells)–labeled cells (Data not shown). GFP expression occurred on days 4–5 post-microinjection and persisted at least for 10 days post-microinjection. No GFP expression was detected in the contralateral L5 DRG (Fig. 1C), ipsilateral L4 DRG (data not shown), ipsilateral L5 spinal cord dorsal horn (Fig. 1D), or brain regions (data not shown). Approximately 47% (78/166) of DRG neurons were positive for GFP. Among these GFP-positive neurons, about 43.5% (40/92) were labeled by CGRP (a marker for small DRG peptidergic neurons), 31.7% (33/104) by IB4 (a marker for small DRG non-peptidergic neurons), and 26.8% (33/123) by NF200 (a marker for large/medium cells and myelinated A fibers) (Fig. 1E). In addition, we found that about 38.3% (49/128) of GFP-positive neurons are labeled for MOR (Fig. 1E). We also carried out a single-cell real-time RT-PCR assay to further verify the subpopulation distribution of the GFP-positive neurons in the DRG. Gapdh mRNA was used as a positive control of viral transduction. Gfp mRNA was detected in approximately 64.2% (43/67) of Gapdh mRNA-expressed DRG neurons randomly collected (Fig. 1F–H). In these DRG neurons, Gfp mRNA was expressed in 86.3% (19/22) of small DRG transduced neurons, 54.6% (12/22) of medium DRG transduced neurons, and 53.2% (12/23) of large DRG transduced neurons (Fig. 1F–H). Moreover, Oprm1 mRNA was detected in 30.2% (13/43) of Gfp mRNA-expressed DRG transduced neurons, in which 52.6% (10/19) of small DRG transduced neurons and 25% (3/12) of medium DRG transduced neurons expressed Oprm1 mRNA (Fig. 1F and G). None of the large DRG transduced neurons expressed Oprm1 mRNA (Fig. 1H).

GFP-labeled HSV is limited in the ipsilateral L5 DRG neurons and their fibers on day 7 after microinjection of HSV-GFP into the unilateral L5 DRG. (A–D) GFP expression in the L5 DRG (A) and L5 spinal nerve (B) on the ipsilateral side. No GFP expression in the contralateral L5 DRG (C) and ipsilateral L5 spinal cord dorsal horn (D). Scale bars, 50 μm. (E) GFP-labeled neurons are positive for CGRP (43.5%), IB4 (31.7%), NF200 (26.8%), and MOR (38.3%) (arrows). n = 3 biological repeats (3 rats). Scale bars, 50 μm. (F–H) Co-expression of Oprm1 mRNA with Gfp mRNA in small (F) and medium (G) DRG neurons, but not in large DRG neurons (H). A representative gel of a single-cell real-time RT-PCR assay (left) and a Venn diagram of Oprm1 mRNA-, Gfp mRNA-, or Gapdh mRNA-expressed neurons in the L5 DRG (right) are shown in (F), (G), and (H)

Consistent with previous studies in mice [7, 27], the microinjected rats revealed no signs of paresis or other abnormalities. The injected DRG, stained with hematoxylin/eosin, retained their structural integrity and contained no visible leukocytes (data not shown) indicating that the immune responses from viral injection were minimal.

Effects of DRG Microinjection of HSV-TET1 on the Development of SNL-Induced Nociceptive Hypersensitivity

SNL produced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia on the ipsilateral (but not contralateral) side of the PBS- or HSV-GFP-microinjected groups from days 3 to 5 after SNL (Fig. 2A–D). These pain hypersensitivities were significantly blocked or abolished on the ipsilateral side after microinjection of HSV-TET1 into the injured L5 DRG (Fig. 2A and B). Paw withdrawal latency to thermal stimulation was not altered compared to baseline, but paw withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation was higher compared to the PBS- or HSV-GFP-microinjected groups during the observation period (Fig. 2A and B). Basal paw withdrawal responses to mechanical and thermal stimuli on the contralateral side of SNL rats, and on both ipsilateral and contralateral sides of sham, rats were not affected after microinjection of either PBS or virus into the injured L5 DRG (Fig. 2A–D). As expected, microinjection of either PBS or virus into intact (ipsilateral) L4 DRG did not alter basal paw withdrawal responses or SNL-induced pain hypersensitivities (data not shown).

Effect of pre-microinjection of HSV-TET1 into the ipsilateral L5 DRG on the SNL-induced pain hypersensitivity during the development period. HSV or PBS was microinjected 3 days before SNL or sham surgery. Paw withdrawal latency to heat stimulation (A, C) and paw withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation (B, D) on the ipsilateral (A, B) and contralateral (C, D) sides. n = 5 rats per group. **p < 0.01 versus the PBS plus HSV-TET1 group at the corresponding time point

Then, methylnaltrexone (MNTX), a peripheral MOR antagonist, was injected intraperitoneally on day 5 after SNL or sham surgery in DRG microinjected rats (Fig. 3A–D). As expected, before the MNTX injection, HSV-TET1-microinjected rats displayed the attenuations of SNL-induced decreases in paw withdrawal latency to thermal stimulation (Fig. 3A) and in paw withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation on the ipsilateral side (Fig. 3C). However, these attenuations were absent after intraperitoneal MNTX administration (Fig. 3A and C). MNTX at the dose used did not affect basal thermal or mechanical responses on the contralateral side (Fig. 3B and D).

Effect of intraperitoneal injection with MNTX on the HSV-TET1-produced antinociceptive effect on day 5 post-SNL on the ipsilateral side. Paw withdrawal latency to heat stimulation (A, B) and paw withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation (C, D) on the ipsilateral (A, C) and contralateral (B, D) sides. n = 5 rats per group. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 versus the HSV-GFP plus sham group at the corresponding time point. #p < 0.05 or ##p < 0.01 versus the HSV-GFP plus SNL group at the corresponding time point

We also determined that overexpressing TET1 in ipsilateral L5 DRG affected nerve injury–induced dorsal horn central sensitization, as evidenced by the increases in p-ERK1/2, a marker for neuronal hyperactivity, and GFAP, a marker for astrocyte hyperactivity, in the dorsal horn after SNL. The amounts of p-ERK1/2 (not total ERK1/2) and GFAP were significantly increased on day 5 post-SNL compared to those after sham surgery in the ipsilateral L5 dorsal horn of the HSV-GFP-microinjected rats (Fig. 4A and B). These increases were not seen in the HSV-TET1-microinjected SNL rats (Fig. 4A and B). Consistent with our previous study [14], SNL did not markedly alter basal expression of TET1 in the ipsilateral L5 DRG of the PBS- or HSV-GFP-microinjected rats (Fig. 4C). As expected, DRG microinjection of HSV-TET1 increased the levels of TET1 in the ipsilateral L5 DRG by 3-fold and 3.2-fold, respectively, on day 5 post-SNL and sham surgery compared to the HSV-GFP-microinjected sham rats (Fig. 4C).

Effect of microinjection of HSV-TET1 into ipsilateral L5 DRG on the SNL-induced dorsal horn central sensitization. Data are shown as the mean and SD. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey test. (A, B) Pre-microinjection of HSV-TET1, but not HSV-GFP, into the ipsilateral L5 DRG significantly blocked SNL-induced increases in the levels of phosphorylated extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1/2 (p-ERK1/2) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the ipsilateral L5 dorsal horn post-SNL. Representative Western blots (A) and a summary of densitometric analysis (B) are shown. n = 3 biological repeats (6 rats) per group. **p < 0.01 versus the corresponding HSV-GFP (GFP) plus sham group. ##p < 0.01 versus the corresponding HSV-GFP plus SNL group. (C) The level of TET1 in ipsilateral L5 DRG was markedly increased from the HSV-TET1 plus SNL or sham group, not from the SNL plus PBS or HSV-GFP group, on day 5 post-SNL. Representative Western blots (top) and a summary of densitometric analysis (bottom) are shown. n = 4 biological repeats (8 rats) per group. **p < 0.01 versus the HSV-GFP plus sham group

Effects of DRG Microinjection of HSV-TET1 on the Maintenance of SNL-Induced Nociceptive Hypersensitivity

Post-microinjection of HSV-TET1, but not HSV-GFP, significantly reduced SNL-induced pain hypersensitivities on the ipsilateral side during the maintenance period (Fig. 5A and B). On days 10 and 12 post-SNL, paw withdrawal latency in response to thermal stimuli increased by 1.2-fold and 1.2-fold, respectively (Fig. 5A), and paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli increased by 1.8-fold and 2.4-fold, respectively (Fig. 5B), in the HSV-TET1-microinjected group compared with the corresponding GFP-microinjected group. As expected, post-microinjection of HSV-GFP or HSV-TET1 did not alter basal paw withdrawal responses to mechanical or thermal stimuli applied to the contralateral hind paw during the maintenance period (Fig. 5C and D).

Effects of post-microinjection of HSV-TET1 into ipsilateral L5 DRG on SNL-induced pain hypersensitivity during the maintenance period. HSV was microinjected on day 6 after SNL or sham surgery. Paw withdrawal latency to heat stimulation (A, C) and paw withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation (B, D) on the ipsilateral (A, B) and contralateral (C, D) sides. Data are shown as the mean and SD. n = 5 rats per group. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 versus the HSV-GFP (GFP) plus SNL group at the corresponding time points

DRG Microinjection of HSV-TET1 Improves Morphine Analgesia and Prevents Its Tolerance Under Neuropathic Pain Conditions

Additionally, we tested if morphine analgesia could be improved after DRG TET1 overexpression in SNL rats. Morphine (3 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected on day 3 after SNL or sham surgery in DRG microinjected rats. The maximal possible analgesic effect (MPAE) of morphine on day 3 post-SNL was dramatically reduced by 58% of the value on day 3 post-sham surgery on the ipsilateral side of the HSV-GFP-microinjected rats (Fig. 6A). This reduction was significantly prevented on the ipsilateral side of HSV-TET1-microinjected SNL rats, as evidenced by an increase by 1.84-fold compared to the corresponding HSV-GFP-microinjected SNL rats (Fig. 6A). As expected, morphine led to robust analgesia on the contralateral side of all microinjected groups (Fig. 6A).

Microinjection of HSV-TET1 into ipsilateral L5 DRG rescued morphine analgesia and attenuated morphine analgesic tolerance in SNL rats. (A). Morphine maximal possible analgesic effects (MPAEs) on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides on day 3 post-SNL or sham surgery. n = 5 rats per group. **p < 0.01 versus the HSV-GFP plus sham group. ##p < 0.01 versus the HSV-GFP plus SNL group. (B, C) Morphine analgesic tolerance on the ipsilateral (B) and contralateral (C) sides post-SNL or sham surgery. n = 5 rats per group. *p < 0.05 versus the HSV-TET1 plus SNL group at the corresponding time point. (D) Dose–response curve of morphine on the ipsilateral side on day 11 post-SNL or post-sham surgery. EC50 values—4.99 for the HSV-TET1 plus SNL group, 4.84 for the HSV-GFP plus sham group, and 6.41 for the HSV-GFP plus SNL group. n = 5 rats/group

We also observed if overexpressing TET1 in the DRG mitigated the development of morphine analgesic tolerance under neuropathic pain conditions. Morphine (10 mg/kg twice daily) was subcutaneously injected for 5 days starting on day 7 post-SNL or sham surgery in microinjection rats (Fig. 6B and C). Repeated injection of morphine led to morphine analgesic tolerance, as indicated by time-dependent decreases in morphine MPAEs on both ipsilateral and contralateral sides of all treated groups (Fig. 6B and C). As expected, the values of morphine MPAEs in the HSV-GFP-microinjected SNL rats were markedly lower than those in the HSV-GFP-microinjected sham rats on the ipsilateral side on days 7, 9, and 11 post-SNL or sham surgery (Fig. 6B). However, these SNL-evoked enhancing reductions in morphine MPAEs were not seen in the HSV-TET1-microinjected SNL rats (Fig. 6B). This effect of DRG TET1 overexpression was also confirmed by a significant leftward shift in the cumulative dose–response curve of morphine in the HSV-TET1-microinjected SNL rats as compared to the HSV-GFP-microinjected SNL rats on the last day after repeated morphine administration (Fig. 6D). The EC50 values of morphine were 6.41 mg/kg in the HSV-GFP-microinjected SNL rats, 4.99 mg/kg in the HSV-TET1-microinjected SNL rats, and 4.84 mg/kg in the HSV-GFP-microinjected sham rats (Fig. 6D).

Effects of DRG Microinjection of HSV-TET1 on Locomotor Activities

To exclude the possibility that the observed effects described above were affected by impairing locomotor activities, we observed locomotor functions including placing, grasping, and righting reflexes in the microinjected rats. None of the microinjected rats produced any effects on placing, grasping, or righting reflexes (Table 2). Hypermobility and convulsions were not seen in any of the microinjected rats. No marked differences in general behaviors, including gait and spontaneous activity, were observed among the microinjected groups.

DRG Microinjection of HSV-TET1 Rescues MOR and Kv1.2 Expression in Ipsilateral L5 DRG After SNL

Finally, we examined if the antinociceptive effect of DRG TET1 overexpression was mediated by rescuing DNMT3a-triggered MOR and Kv1.2 downregulation in the ipsilateral L5 DRG after peripheral nerve injury. We first carried out in vitro DRG neuronal culture to examine direct effect of TET1 overexpression on DNMT3a-triggered MOR and Kv1.2 downregulation in the DRG neurons. Overexpression of DNMT3a through transduction of AAV5-DNMT3a decreased the levels of MOR and Kv1.2 proteins (Fig. 7A). This decrease could be restored by co-transduction of HSV-TET1 and AAV5-DNMT3a (Fig. 7A). Co-transduction of HSV-TET1 and AAV5-GFP did not alter basal expression of MOR and Kv1.2 (Fig. 7A). In our in vivo study, microinjection of HSV-TET1, but not PBS and HSV-GFP, significantly reversed the reduction of MOR and Kv1.2 protein in the ipsilateral L5 DRG on day 5 post-SNL (Fig. 7B). As expected, no basal changes in MOR and Kv1.2 expression were observed in the contralateral L5 DRG among the treated groups (data not shown). Interestingly, microinjection of HSV-TET1 did not rescue the SNL-induced downregulation of Nav1.9 protein in the ipsilateral L5 DRG (Fig. 7C). This microinjection also did not affect basal expression of cytosolic protein S6K, nuclear protein TET2 (Fig. 7C), or the basal expression of proenkephalin mRNA and proopiomelanocortin mRNA in ipsilateral L5 DRG of SNL rats (Fig. 7D).

Microinjection of HSV-TET1 into ipsilateral L5 DRG rescued the expression of MOR and Kv1.2 from the ipsilateral L5 DRG after SNL. (A) The expression of MOR and Kv1.2 in cultured DRG neurons from adult rats. Representative Western blots (left) and a summary of densitometric analysis (right) are shown. n = 3 biological replicates (6 rats) per group. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 versus the corresponding AAV5-GFP plus HSV-GFP group. #p < 0.05 versus the corresponding AAV5-DNMT3a plus HSV-GFP group. (B, C) The expression of MOR (B), Kv1.2 (B), Nav1.9 (C), S6K (C), and TET2 (C) in ipsilateral L5 DRG 5 days after SNL or sham surgery. Representative Western blots (top) and a summary of densitometric analysis (bottom) are shown. n = 3–5 biological replicates (6–10 rats) per group. *p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 versus the corresponding HSV-GFP plus sham group. ##p < 0.01 versus the corresponding PBS plus SNL group. (D) The expression of endogenous opioid ligand precursors, proenkephalin mRNA and proopiomelanocortin mRNA, in ipsilateral L5 DRG 5 days after SNL or sham surgery. Ipsi = ipsilateral; Cont = contralateral. n = 3 biological replicates (6 rats) per group

Furthermore, SNL produced a substantial increase in the amounts of 5mC and a corresponding decrease in the level of 5hmC in 2 regions (− 450 to − 288 and + 238 to + 439) of the Oprm1 gene and 1 region (− 663 to − 389) of the Kcna2 gene in the ipsilateral L5 DRG of the HSV-GFP-microinjected rats on day 5 post-SNL (Fig. 8A–C). However, in the ipsilateral L5 DRG of HSV-TET1-microinjeced SNL rats, an increase in 5mC was not found, and the level of 5hmC was conversely increased in these regions (Fig. 8A–C). As expected, microinjection of HSV-TET1 into sham DRG did not affect either basal expression of MOR and Kv1.2 or basal amounts of 5mC and 5hmC in 2 regions (− 450 to − 288 and + 238 to + 439) of the Oprm1 gene (Fig. 8A and B) and 1 region (− 663 to − 389) of the Kcna2 gene in the injected DRG (Fig. 8C).

Microinjection of HSV-TET1 into ipsilateral L5 DRG blocked SNL-induced increase in 5mC and decrease in 5hmC in the Oprm1 and Kcna2 genes from the ipsilateral L5 DRG 5 days after SNL. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey test. (A, B) The levels of 5mC (A) and 5hmC (B) in the 2 regions (− 450/− 288, + 238/+ 439) of the Oprm1 gene. n = 3 biological replicates (6 rats) per group. **p < 0.01 versus the corresponding PBS plus sham group. ##p < 0.01 versus the corresponding HSV-GFP plus SNL group. (C) The levels of 5mC and 5hmC in the region (− 663/− 389) of the Kcna2 gene. n = 3 biological replicates (6 rats) per group. **p < 0.01 versus the corresponding PBS plus sham group. #p < 0.05 or ##p < 0.01 versus the corresponding HSV-GFP plus SNL group

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that DRG TET1 overexpression alleviated pain hypersensitivity during the development and maintenance periods of neuropathic pain. This overexpression also rescued morphine analgesia and prevented morphine analgesic tolerance development under neuropathic pain conditions. Mechanistically, DRG TET1 overexpression rescued the expression of MOR and Kv1.2 in the ipsilateral L5 DRG through blocking peripheral nerve injury–induced increases in DNA methylation in the Oprm1 and Kcna2 genes. Given that DRG TET1 overexpression did not alter acute pain or locomotor function, our data suggest that overexpressing TET1 in the DRG may open a new avenue for chronic neuropathic pain management.

HSV has been used as the delivery vehicle for the transduction of targeted genes, particularly for those that are more than 3 kb in molecular weight, in the preclinical animal models [28,29,30,31,32] and clinical trials [33]. However, it is unknown which types of DRG cells are transduced by HSV after either subcutaneous injection or nerve/DRG microinjection of HSV-GFP, as the injected HSV-GFP, unlike the injected AAV-GFP, cannot be observed in the DRG directly under the fluorescent microscope [28,29,30,31,32]. The present study used the immunostaining of anti-GFP antibody and a single-cell real-time RT-PCR assay of Gfp mRNA to firstly report that the microinjected HSV is limited to the microinjected DRG neurons and their fibers. About 50% of DRG neurons were transduced by HSV. A majority of these transduced DRG neurons were small in size. MOR was detected in more than 30% of the transduced DRG neurons, predominantly in small DRG neurons, which is consistent with the fact that MOR is expressed predominantly in small DRG neurons [7, 8].

Recent work suggests the involvement of TET1 in pathological pain. TET1 is expressed exclusively in the neurons of the DRG and spinal cord dorsal horn [34, 35], 2 major pain-related regions in the nervous system. Peripheral SNL and paw injection of formalin or complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) increased TET1 expression in ipsilateral spinal cord dorsal horn, but not in the DRG [14, 34,35,36,37,38]. Knockdown of spinal TET1 alleviated the formalin-, CFA-, and SNL-induced nociceptive behaviors through blocking TET1-triggered expression of dorsal horn miR-365, Stat3, and BDNF, respectively [35, 37, 38]. Overexpression of TET1 in the spinal cord led to pain-like behaviors [35, 37, 38]. These findings suggest that endogenous TET1 in the spinal cord may contribute to the genesis of both neuropathic pain and inflammatory pain. However, directly targeting spinal cord TET1 is impractical in clinical neuropathic pain management, as surgically opening vertebrate is required. In addition, selective and specific TET1 inhibitors are unavailable currently.

Recent studies demonstrated that DNMT3a-triggered epigenetic silencing of the Oprm1 and Kcna2 genes in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury contributes to neuropathic pain genesis. SNL increased expression of DNMT3a in ipsilateral L5 DRG neurons [8, 14]. This increase participated in SNL-induced DRG MOR and Kv1.2 downregulation and pain hypersensitivity likely through DNMT3a-triggered elevations in DNA methylation at sites − 365 and + 387 of the Oprm1 gene and at sites − 457 and − 444 of the Kcna2 gene in ipsilateral L5 DRG [8, 14]. These findings suggest that targeting elevated DNA methylation in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury could be a new approach to treat neuropathic pain. Given that TET1 was reported to possibly regulate opioid receptors [39], we overexpressed TET1 in ipsilateral L5 DRG through microinjection of HSV-TET1 in the present study. As expected, this microinjection blocked the SNL-induced increase in the level of 5mC and restored the SNL-induced decrease in the amount of 5hmC in the regions of the Oprm1 (− 450/− 288 and + 238/+ 439) and Kcna2 (− 663/− 389) genes from ipsilateral L5 DRG. This suggests that overexpression of TET1 in the DRG likely attenuates the DNMT3a-induced increases in DNA methylation at sites − 365 and + 387 of the Oprm1 gene and at sites − 457 and − 444 of the Kcna2 gene in the injured DRG. More importantly, DRG microinjection of HSV-TET1 rescued MOR and Kv1.2 expression in the ipsilateral L5 DRG, mitigated pain hypersensitivity, restored morphine analgesia, and attenuated morphine analgesic tolerance development under SNL-induced neuropathic pain conditions. Given that DRG microinjection of HSV-TET1 did not affect the expression of endogenous MOR ligand precursors proenkephalin mRNA and proopiomelanocortin mRNA in the ipsilateral L5 DRG of sham or SNL rats, our data suggest that overexpression of exogenous TET1 in DRG produces an antinociceptive effect under SNL-induced neuropathic pain conditions at least through its triggered demethylation of the Oprm1 and Kcna2 genes and subsequent rescue of MOR and Kv1.2 expression in ipsilateral L5 DRG. Nevertheless, demethylation of other genes, promoted by overexpression of exogenous TET1 in DRG under neuropathic pain conditions, cannot be ruled out. Previous studies reported TET1-dependent demethylation at the promoter of the mGluR5 and bdnf genes, resulting in promotion in expression of mGluR5 and BNNF in dorsal horn neurons following peripheral nerve injury [35, 36]. Whether HSV-TET1 microinjection affects mGluR5 and BDNF expression in the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury still remains to be determined. Overexpression of TET1 in the DRG may selectively affect nerve injury–induced changes in some gene expression since SNL-induced downregulation of DRG Nav1.9 was not rescued through microinjection of HSV-TET1 into ipsilateral L5 DRG. DRG microinjection of HSV-TET1 also did not alter basal expression of S6K and TET2 proteins in ipsilateral L5 DRG of SNL rats, further demonstrating selectivity of TET1 targeting genes. It is very likely that TET1-triggered demethylation in the promoter regions of some specific genes makes them accessible to the transcription factors, leading to gene transcriptional activation [15]. In addition, TET1-triggered demethylation possibly inhibits DNMT3a from binding to the promoter regions of the gene [35], even though DNMT3a expression is increased in the DRG ipsilateral nerve injury [8, 14]. Given that the HSV-mediated transgene is expressed exclusively in the neurons and their fibers [40], exogenous TET1, through microinjection of HSV-TET1 into the DRG ipsilateral to nerve injury, may directly regulate the expression of some specific pain-associated genes, including Oprm1 and Kcna2, in individual DRG neurons.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that DRG TET1 overexpression, through microinjection of HSV-TET1, significantly alleviated pain hypersensitivity, rescued opioid analgesia, and prevented opioid tolerance development under neuropathic pain conditions. The present study may provide a potential avenue in neuropathic pain prevention and treatment given that this microinjection produced local effects on gene expression and did not alter acute pain or motor function, and that HSV-mediated gene therapy has been used in clinical trial [33, 41].

References

van HO, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N (2014) Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain 155: 654–662. S0304–3959(13)00610–6 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013.

Campbell JN, Meyer RA (2006) Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron 52: 77–92.

Devor M (2009) Ectopic discharge in Abeta afferents as a source of neuropathic pain. Exp Brain Res 196: 115–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-009-1724-6.

Poetsch AR, Plass C (2011) Transcriptional regulation by DNA methylation. Cancer Treat Rev 37 Suppl 1: S8–12.

Liang L, Lutz BM, Bekker A, Tao YX (2015) Epigenetic regulation of chronic pain. Epigenomics 7: 235–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.2217/epi.14.75.

Bian EB, Zong G, Xie YS, Meng XM, Huang C, Li J, Zhao B (2014) TET family proteins: new players in gliomas. J Neurooncol 116: 429–435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-013-1328-7.

Liang L, Zhao JY, Gu X, Wu S, Mo K, Xiong M, Bekker A, Tao YX (2016) G9a inhibits CREB-triggered expression of mu opioid receptor in primary sensory neurons following peripheral nerve injury. Mol Pain 12: 1–16.

Sun L, Zhao JY, Gu X, Liang L, Wu S, Mo K, Feng J, Guo W, Zhang J, Bekker A, Zhao X, Nestler EJ, Tao YX (2017) Nerve injury-induced epigenetic silencing of opioid receptors controlled by DNMT3a in primary afferent neurons. Pain 158: 1153–1165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000894.

Mansikka H, Zhao C, Sheth RN, Sora I, Uhl G, Raja SN (2004) Nerve injury induces a tonic bilateral mu-opioid receptor-mediated inhibitory effect on mechanical allodynia in mice. Anesthesiology 100: 912–921.

Stein C, Zollner C (2009) Opioids and sensory nerves. Handb Exp Pharmacol 495–518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_14.

Yaksh TL (1988) Substance P release from knee joint afferent terminals: modulation by opioids. Brain Res 458: 319–324. .

Fan L, Guan X, Wang W, Zhao JY, Zhang H, Tiwari V, Hoffman PN, Li M, Tao YX (2014) Impaired neuropathic pain and preserved acute pain in rats overexpressing voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.2 in primary afferent neurons. Mol Pain 10: 8. 1744-8069-10-8 doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-10-8.

Zhao X, Tang Z, Zhang H, Atianjoh FE, Zhao JY, Liang L, Wang W, Guan X, Kao SC, Tiwari V, Gao YJ, Hoffman PN, Cui H, Li M, Dong X, Tao YX (2013) A long noncoding RNA contributes to neuropathic pain by silencing Kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat Neurosci 16: 1024–1031. nn.3438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3438.

Zhao JY, Liang L, Gu X, Li Z, Wu S, Sun L, Atianjoh FE, Feng J, Mo K, Jia S, Lutz BM, Bekker A, Nestler EJ, Tao YX (2017) DNA methyltransferase DNMT3a contributes to neuropathic pain by repressing Kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat Commun 8: 14712. ncomms14712. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14712.

He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, Ding J, Jia Y, Chen Z, Li L, Sun Y, Li X, Dai Q, Song CX, Zhang K, He C, Xu GL (2011) Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science 333: 1303–1307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1210944.

Kim SH, Chung JM (1992) An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain 50: 355–363.

Han PJ, Shukla S, Subramanian PS, Hoffman PN (2004) Cyclic AMP elevates tubulin expression without increasing intrinsic axon growth capacity. Exp Neurol 189: 293–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.03.010.

Xu Y, Gu Y, Xu GY, Wu P, Li GW, Huang LY (2003) Adeno-associated viral transfer of opioid receptor gene to primary sensory neurons: a strategy to increase opioid antinociception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 6204–6209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0930324100.

Liaw WJ, Zhu XG, Yaster M, Johns RA, Gauda EB, Tao YX (2008) Distinct expression of synaptic NR2A and NR2B in the central nervous system and impaired morphine tolerance and physical dependence in mice deficient in postsynaptic density-93 protein. Mol Pain 4: 45. 1744-8069-4-45 doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-4-45.

Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL (1994) Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 53: 55–63.

Park JS, Voitenko N, Petralia RS, Guan X, Xu JT, Steinberg JP, Takamiya K, Sotnik A, Kopach O, Huganir RL, Tao YX (2009) Persistent inflammation induces GluR2 internalization via NMDA receptor-triggered PKC activation in dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci 29: 3206–3219. 29/10/3206 doi:https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4514-08.2009.

Lee CY, Perez FM, Wang W, Guan X, Zhao X, Fisher JL, Guan Y, Sweitzer SM, Raja SN, Tao YX (2011) Dynamic temporal and spatial regulation of mu opioid receptor expression in primary afferent neurons following spinal nerve injury. Eur J Pain 15: 669–675.

Li Z, Gu X, Sun L, Wu S, Liang L, Cao J, Lutz BM, Bekker A, Zhang W, Tao YX (2015) Dorsal root ganglion myeloid zinc finger protein 1 contributes to neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve trauma. Pain 156: 711–721. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000103.

Zhang J, Liang L, Miao X, Wu S, Cao J, Tao B, Mao Q, Mo K, Xiong M, Lutz BM, Bekker A, Tao YX (2016) Contribution of the Suppressor of Variegation 3-9 Homolog 1 in Dorsal Root Ganglia and Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn to Nerve Injury-induced Nociceptive Hypersensitivity. Anesthesiology 125: 765–778. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001261.

Tsai YP, Chen HF, Chen SY, Cheng WC, Wang HW, Shen ZJ, Song C, Teng SC, He C, Wu KJ (2014) TET1 regulates hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by acting as a co-activator. Genome Biol 15: 513. s13059–014–0513-0 doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0513-0.

Eichten SR, Briskine R, Song J, Li Q, Swanson-Wagner R, Hermanson PJ, Waters AJ, Starr E, West PT, Tiffin P, Myers CL, Vaughn MW, Springer NM (2013) Epigenetic and genetic influences on DNA methylation variation in maize populations. Plant Cell 25: 2783–2797. doi:https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.114793.

Liang L, Gu X, Zhao JY, Wu S, Miao X, Xiao J, Mo K, Zhang J, Lutz BM, Bekker A, Tao YX (2016) G9a participates in nerve injury-induced Kcna2 downregulation in primary sensory neurons. Sci Rep 6: 37704.

Guedon JM, Wu S, Zheng X, Churchill CC, Glorioso JC, Liu CH, Liu S, Vulchanova L, Bekker A, Tao YX, Kinchington PR, Goins WF, Fairbanks CA, Hao S (2015) Current gene therapy using viral vectors for chronic pain. Mol Pain 11: 27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12990-015-0018-1.

Hao S, Mata M, Wolfe D, Huang S, Glorioso JC, Fink DJ (2003) HSV-mediated gene transfer of the glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor provides an antiallodynic effect on neuropathic pain. Mol Ther 8: 367–375.

Hao S, Mata M, Goins W, Glorioso JC, Fink DJ (2003) Transgene-mediated enkephalin release enhances the effect of morphine and evades tolerance to produce a sustained antiallodynic effect in neuropathic pain. Pain 102: 135–142.

Hao S, Mata M, Glorioso JC, Fink DJ (2006) HSV-mediated expression of interleukin-4 in dorsal root ganglion neurons reduces neuropathic pain. Mol Pain 2: 6. 1744-8069-2-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-2-6.

Hao S, Liu S, Zheng X, Zheng W, Ouyang H, Mata M, Fink DJ (2011) The role of TNFalpha in the periaqueductal gray during naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 664–676. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.197.

Fink DJ, Wechuck J, Mata M, Glorioso JC, Goss J, Krisky D, Wolfe D (2011) Gene therapy for pain: results of a phase I clinical trial. Ann Neurol 70: 207–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22446.

Chamessian AG, Qadri YJ, Cummins M, Hendrickson M, Berta T, Buchheit T, Van d, V (2017) 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and Ten-eleven translocation 1–3 (TET1–3) proteins in the dorsal root ganglia of mouse: Expression and dynamic regulation in neuropathic pain. Somatosens Mot Res 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08990220.2017.1292237.

Hsieh MC, Lai CY, Ho YC, Wang HH, Cheng JK, Chau YP, Peng HY (2016) Tet1-dependent epigenetic modification of BDNF expression in dorsal horn neurons mediates neuropathic pain in rats. Sci Rep 6: 37411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37411.

Hsieh MC, Ho YC, Lai CY, Chou D, Wang HH, Chen GD, Lin TB, Peng HY (2017) Melatonin impedes Tet1-dependent mGluR5 promoter demethylation to relieve pain. J Pineal Res e12436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12436.

Pan Z, Zhang M, Ma T, Xue ZY, Li GF, Hao LY, Zhu LJ, Li YQ, Ding HL, Cao JL (2016) Hydroxymethylation of microRNA-365-3p Regulates Nociceptive Behaviors via Kcnh2. J Neurosci 36: 2769–2781. 36/9/2769. doi:https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3474-15.2016.

Pan Z, Xue ZY, Li GF, Sun ML, Zhang M, Hao LY, Tang QQ, Zhu LJ, Cao JL (2017) DNA Hydroxymethylation by Ten-eleven Translocation Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 1 and 3 Regulates Nociceptive Sensitization in a Chronic Inflammatory Pain Model. Anesthesiology 127: 147–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001632.

Hwang CK, Wagley Y, Law PY, Wei LN, Loh HH (2015) Analysis of epigenetic mechanisms regulating opioid receptor gene transcription. Methods Mol Biol 1230: 39–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1708-2_3.

Maze I, Covington HE, III, Dietz DM, LaPlant Q, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Mechanic M, Mouzon E, Neve RL, Haggarty SJ, Ren Y, Sampath SC, Hurd YL, Greengard P, Tarakhovsky A, Schaefer A, Nestler EJ (2010) Essential role of the histone methyltransferase G9a in cocaine-induced plasticity. Science 327: 213–216. 327/5962/213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1179438.

Wolfe D, Mata M, Fink DJ (2012) Targeted drug delivery to the peripheral nervous system using gene therapy. Neurosci Lett 527: 85–89. S0304–3940(12)00581–2 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2012.04.047.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Dr. Wanhong Zuo for the single-cell collection and acknowledge Ms. Jamie Bono for the assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants (R01NS094664, R01NS094224, and R01DA033390) for YXT, the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81471352) for MC, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2682016CX103) for GW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X.T. and M.C. conceived the project and supervised all experiments. Q.W., G.W., F.J., S.J., and Y.X.T. designed the project. Q.W., F.J., X.G., X.M., and S.J. performed the animal model, conducted behavioral experiments, and carried out microinjection and DRG culture. G.W., X.G., L.H., and F.J. carried out Western blot, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and PCR experiments. Z.P., Y.Y., and Q.M. helped with Western blot and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. S.W. constructed HSV-TET1 and carried out PCR. Q.W., S.J., M.C., and Y.X.T. analyzed the data. Q.W., M.C., and Y.X.T. wrote the manuscript. All of the authors read and discussed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

All procedures used were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School (Newark, New Jersey).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Q., Wei, G., Ji, F. et al. TET1 Overexpression Mitigates Neuropathic Pain Through Rescuing the Expression of μ-Opioid Receptor and Kv1.2 in the Primary Sensory Neurons. Neurotherapeutics 16, 491–504 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-00689-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-00689-x