Abstract

Introduction

Although there were initial concerns that the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic would adversely affect glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes, several early continuous glucose monitor (CGM) studies reported an unexpected slight improvement in glucose metrics. Early emerging adulthood (roughly spanning the ages of 18–24 years) is often a vulnerable time in the life of a person with type 1 diabetes. Here, we set out to determine how the care and glucose management of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes changed over a period of approximately 2 years from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of a tertiary referral, multidisciplinary young adult diabetes clinic, spanning before and after the 777-day state of emergency in the City of Toronto.

Results

Of 130 emerging adults with type 1 diabetes (80 male, 50 female; mean age 21.0 ± 2.1 years), baseline pre-pandemic HbA1c values were available for 120 individuals. During 24.9 ± 5.4 months of follow-up before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, HbA1c fell from 8.5 ± 1.7% (69.3 ± 18.8 mmol/mol) to 8.1 ± 1.9% (65.2 ± 20.5 mmol/mol) (P < 0.05), with change in HbA1c from pre-lockdown levels being sustained throughout the second year of the pandemic. Over the same period, CGM use rose from 43% to 83%, primarily through increased uptake of intermittently scanned CGM, which is covered through the Ontario Drug Benefit program. Change in HbA1c was most evident in Dexcom G6 real-time CGM users − 0.7 ± 1.2% (− 9.8 ± 17.1 mmol/mol) (P < 0.01 vs. self-monitoring of blood glucose).

Conclusion

Among emerging adults with type 1 diabetes attending a multidisciplinary clinic in a high-income country, glycated hemoglobin levels are on average 0.4% (4.1 mmol/mol) lower than they were before the pandemic. This reduction in HbA1c is unlikely to be a consequence of early strict lockdowns given the length of time of follow-up. Rather, improved glycemic control coincided with increased utilization of wearable diabetes devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Diabetes care delivery has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there is limited information as to how this has affected emerging adults, an especially vulnerable group. |

This study examined how care and glycemic control of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes have changed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. |

What was learned from the study? |

Over an approximate 2-year period, among a cohort of 130 emerging adults with type 1 diabetes, HbA1c improved on average by 0.4%. |

This glycemic improvement accompanied large increases in diabetes technology use, particularly use of continuous glucose monitors. |

Supporting wider advocacy for broader access, glycemic improvements were most evident among emerging adults with type 1 diabetes using real-time continuous glucose monitors. |

Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic [1]. Since that moment, the delivery of healthcare has transformed at a rate and in ways that had not been foreseen. In the months following the WHO statement, public health lockdowns in jurisdictions throughout the world shifted diabetes care from the traditional in-person visit model to ‘virtual care’, or telemedicine. Even 2 years after the gradual easing of lockdown measures, ongoing COVID-19 infections and risk, system backlogs, and healthcare worker shortages have meant that healthcare delivery has not returned to its pre-pandemic ‘normal’ [2]. For people living with type 1 diabetes, however, the transformation in the way healthcare is accessed has coincided with a technological transformation with improvements in, and improved access to, wearable devices for insulin delivery and glucose monitoring. In the acute aftermath of the public health lockdowns, data from glucose-sensing devices revealed that, contrary to initial expectations, glycemic control did not deteriorate in people with type 1 diabetes following ‘stay-at-home’ orders and, in many cases, there were modest improvements [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Several, explanations have been given for the absence of deterioration and possible improvement of glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes during COVID-19 lockdowns. These include increased time and opportunity at home to engage in self-management, plan meals, count carbohydrates and ‘pre-bolus’; greater opportunity for parental vigilance for children living with type 1 diabetes; increased sleep duration; increased utilization of insulin pumps, continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and hybrid closed loops; and increased use of cloud-based glucose monitoring by healthcare providers [11, 13, 14]. What has been unclear, however, is whether improvements in glycemic control during COVID-19 lockdowns are sustained during the reopening of society.

Early emerging adulthood (roughly spanning the ages of 18–24 years [16]) is an especially challenging period in the life of a person with type 1 diabetes [17,18,19,20]. Early emerging adults (henceforward termed emerging adults) have the highest HbA1c levels and the lowest use of insulin pumps and CGMs out of any age group with type 1 diabetes [21]. In an effort to smooth the transition during the emerging adult years, many centres including our own provide dedicated, multidisciplinary young adult or ‘transition’ clinics for those with diabetes transitioning from pediatric care [22]. Whereas some previous reports of glycemic control in type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic have included emerging adults within their analyses [5, 10, 12], there is a dearth of literature as to how this at-risk group fared in particular.

On 13 March 2020, in response to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, the universities of Toronto announced the cancellation of in-person classes and a shift to online learning [23]. A state of emergency was declared by the province of Ontario on 17 March 2020 [24] and by the City of Toronto on 23 March 2020 [25]. The City of Toronto state of emergency lasted a total of 777 days before it was finally lifted on 9 May 2022 [26], making it one of the longest running COVID-19 state of emergencies in the world. During this period, public health restrictions tightened and eased according to COVID-19 infection rates and hospital pressures. At St. Michael’s Hospital in downtown Toronto, virtual care was made available to all patients throughout the state of emergency, with in-person visits initially limited but later encouraged with the waning of the COVID-19 Alpha, Delta and Omicron variant waves. Given the length of the Toronto public health restrictions and our established multidisciplinary young adult diabetes service, we set out to answer the question: How were the care and glucose management of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes affected during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

Clinic Structure and Adjustment to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The Young Adult Diabetes Clinic at St. Michael’s Hospital was established in 2011 to provide care for emerging adults with diabetes aged 18–24 years. It is a multidisciplinary clinic supported by an endocrinologist, a registered nurse and certified diabetes educator (CDE), a registered dietician and CDE, and a social worker. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the clinic ran on three afternoons each month. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the last in-person clinic was held on 12 March 2020. After that, some clinic staff were redeployed to the hospital’s COVID Assessment Centre. Care at the Young Adult Diabetes Clinic continued virtually, which largely involved scheduled phone call appointments and ad hoc email check-ins. Video conferencing occurred very occasionally between patients and the allied health team, but not with the physician. During the following 2 years, in-person care gradually resumed although phone call appointments were still made available for patients who requested them up to the time of censure.

Changes in the Landscape of Diabetes Technologies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The costs of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) products (insulin pumps) for people with type 1 diabetes are covered by the province of Ontario’s assisted device program (ADP). In September 2019, before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Freestyle Libre flash CGM, or intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitor (isCGM), was covered by the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) program. Thus, isCGM is available at no cost to emerging adults living with type 1 diabetes (who do not have private insurance) through the Ontario Health Insurance Plan plus (OHIP+) program. Reimbursement through ODB for the Freestyle Libre 2 system became effective in November 2021. In March 2022, the province’s ADP program approved coverage for real-time continuous glucose monitoring (rtCGM) systems. However, access to rtCGM coverage through the ADP program is restricted to those with recent debilitating severe hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness and it is limited in its scope. In terms of hybrid closed loop technologies, the Medtronic 670G insulin pump with Auto Mode was approved by Health Canada in October 2018; the Tandem t:slim X2 insulin pump with Basal-IQ predictive low-glucose suspend received approval in November 2019 and the Control-IQ hybrid closed loop system received Health Canada approval in November 2020. Thus, paralleling major changes in the delivery of healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic, over the same period emerging adults living with type 1 diabetes in Ontario gained increasing access to advanced insulin delivery systems and, in particular, glucose-sensing technologies.

Review of the Care of Emerging Adults with Type 1 Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic

To determine how the care and glucose management of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes were affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to virtual care, and the concurrent rapid emergence of diabetes technologies, we reviewed the charts of attendees at the St. Michael’s Hospital Young Adult Diabetes Clinic. The period of review extended from the last physician visit in the year prior to lockdown (i.e. last clinic visit between 12 March 2019 and 12 March 2020 (inclusive), ‘pre-lockdown assessment’) up to the most recent physician visit prior to censure (25 May 2022; ‘last assessment’). Inclusion criteria were individual attendees at the Young Adult Diabetes Clinic aged 18–24 years with a clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Data were obtained from patients’ medical records, de-identified and stored in a password-protected file on the hospital network. Information collected included age, duration of diabetes, sex, method of insulin administration, method of glucose measurement, laboratory HbA1c, number and nature of visits with the diabetes care team and CGM metrics where available. The study was approved by the Unity Health Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB# 22-123), and it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent for the retrospective review was waived.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Fisher least significant difference post-test or paired or unpaired two-tailed Student t test as appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 for macOS (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics of the Emerging Adult Population

A total of 130 emerging adults with type 1 diabetes (80 male, 50 female; mean age 21.0 ± 2.1 years) were included in the assessment (Table 1). Of these, 103 were seen both prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and during the follow-up period; 15 (11.5%) were lost to follow-up [baseline HbA1c of those lost to follow-up, 8.8 ± 1.2% (73.1 ± 13.3 mmol/mol)]; there were 6 new patients (4.6%; 5 of whom were referred from a pediatric service) and 6 (4.6%) patients returned to the clinic having not been seen in the prior year (Table 1). The mean interval between pre-lockdown assessment and last assessment was 24.9 ± 5.4 months, during which time the patients had contact with a healthcare provider on average on around 10 occasions, with approximately 80% virtual visits (phone calls) (Table 1). Patterns of interactions (virtual or in-person) with different diabetes care team members (physician, registered nurse, registered dietician, and social worker) are shown in Table 1.

Glycemic Control as Determined by Laboratory HbA1c

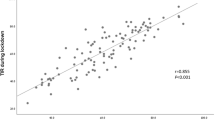

Laboratory HbA1c values were available for 120 patients at their visit in the year prior to the introduction of virtual care and 109 patients on follow-up (Fig. 1). The median time from pre-lockdown assessment to start of lockdown was 3 months (range 0–11 months). Mean HbA1c was 8.5 ± 1.7% (69.3 ± 18.8 mmol/mol) on pre-lockdown assessment and 8.1 ± 1.9% (65.2 ± 20.5 mmol/mol) on follow-up (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1a). Change in HbA1c from pre-lockdown levels was sustained throughout the second year of the pandemic (Fig. 1b). Of the 29 patients who had HbA1c values available both pre-pandemic and after 24 months, 15 patients had serial HbA1c measurements indicating contact with the clinic during the pandemic, whereas for 14 patients no interval HbA1c measurements were available, suggesting the return of patients after a period of absence. Among these 29 patients, change in HbA1c tended to be lower in those who had had contact with the clinic between assessments (change in HbA1c for serial assessments (n = 15) − 0.4 ± 1.4% (− 4.9 ± 15.0 mmol/mol) and for returning patients (n = 14) 0.5 ± 1.2% (5.0 ± 12.8 mmol/mol); P = 0.0522 by Mann–Whitney test).

Improvement in HbA1c in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. a Laboratory HbA1c values for emerging adults with type 1 diabetes at their most recent visits prior to and including 12 March 2020 (pre-lockdown assessment, n = 120) and 25 May 2022 (last assessment, n = 109). b Change in HbA1c over the course of the follow-up period from 13 March 2020 to 25 May 2022. *P < 0.05 by two-tailed paired Student t test

Methods of Insulin Administration and Glucose Measurement

During the assessment period, there were notable shifts in the use of insulin pumps and CGMs among emerging adults with type 1 diabetes. At first assessment, 59/130 (45%) of patients were recorded as wearing an insulin pump (Table 2). At last assessment, this had risen modestly to 67 patients (52%) (Table 2). Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) was recorded as being used by more than half of patients at first assessment (69/130, 53%) (Table 2), with 43% of patients using isCGM or real-time CGM (rtCGM) (Table 2). By final assessment, only 19 patients (15%) were noted to be using SMBG, with data not available for 16 patients (12%). The largest change was in the use of the Freestyle Libre flash glucose monitor, which rose from 29 patients (22%) at pre-lockdown assessment to 54 patients (42%) at last assessment. Those using the Dexcom G6 rtCGM rose from 21 (16%) at pre-lockdown assessment to 34 (26%) at last assessment (Table 2). In total, of the 114 patients for whom data were available at follow-up, 95 (83%) were using some form of glucose-sensing technology.

Change in HbA1c According to Method of Insulin Administration and Glucose Monitoring

Given the statistically significant drop in HbA1c values during more than 2 years of follow-up and the increase in the use of wearable devices for insulin administration and especially glucose-sensing over this period, we set out to determine whether the decline in HbA1c in the entire cohort was related to use of technologies. Table 3 shows the most recent laboratory HbA1c and change in HbA1c for emerging adults with type 1 diabetes according to method of insulin administration and glucose monitoring. As expected, HbA1c was lower in those using CSII than those using multiple daily injections of insulin (MDI), whereas change in HbA1c during the pandemic was not significantly different according to method of insulin administration. At the end of the follow-up period, there was no overall difference in HbA1c between those using SMBG and isCGM, whereas HbA1c levels were significantly lower among users of Dexcom G6 than the Freestyle Libre; change in HbA1c was most apparent in Dexcom G6 users (Table 3).

CGM Metrics

Recognizing the increase in use of glucose-sensing technologies, we lastly examined documented CGM metrics in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes before the COVID-19 pandemic and at their last assessment. At their last pre-pandemic visit, CGM metrics were available for 24 patients. At the last visit before censure on 25 May 2022, CGM metrics were available for 56 patients (Table 4). As expected, and aligned with laboratory HbA1c data, estimated HbA1c (which includes estimated A1c and glucose management indicator, GMI) was significantly lower at last assessment than pre-lockdown assessment (Table 4). Among those for whom CGM metrics were available at the end of the study period (Table 4), time in range (TIR; sensor glucose 3.9–10.0 mmol/L) was higher and time below range (TBR; sensor glucose < 3.9 mmol/L) was lower in emerging adults using rtCGM in comparison to those using isCGM: TIR (%), rtCGM 67.3 ± 13.8, isCGM 48.1 ± 16.6, P < 0.0001; TBR (%), rtCGM 1.6 ± 1.5, isCGM 5.9 ± 5.8, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student t test.

Discussion

When the COVID-19 pandemic first prompted the delivery of healthcare to transition from its historical in-person model to telemedicine, there were initial concerns that restriction in access to care may have deleterious consequences for people living with diabetes. In the short term, CGM-based studies assuaged these concerns, reporting no deterioration and oftentimes a modest improvement in metrics of glycemic control during strict COVID-19 lockdowns [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, as lockdowns were lifted it was unclear whether these initial gains would be sustained or replaced. Here, we report that after approximately 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic, in a cohort of 130 emerging adults with type 1 diabetes, mean laboratory HbA1c was approximately 0.4% (4.1 mmol/mol) lower than it was before the pandemic. This improvement in HbA1c coincided with shifts in the use of diabetes technologies, most notably in an increase in the uptake of isCGM and rtCGM.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, early reports suggested that people with diabetes were at increased risk of severe infection [27,28,29], with larger epidemiological data subsequently confirming an approximately 3.5-fold increase in risk of COVID-19-related death among individuals living with type 1 diabetes [30]. It has been proposed that awareness of this increase in risk and resultant greater attention paid to self-management behaviours may have contributed to improvements in TIR reported among CGM users with type 1 diabetes during the initial strict COVID-19 lockdowns that started in March 2020 [3, 14, 31]. However, emerging adulthood is often a time of risk-taking [32], COVID-19 vaccines are now widely available throughout Canada and were mandated by higher education establishments [33], and the City of Toronto has a COVID-19 vaccination rate of approximately 90% [34]. Thus, it seems unlikely that sustained fear of severe COVID-19 outcomes was responsible for the reduction in HbA1c in our emerging adult population 2 years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas most [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] but not all [35, 36] studies have shown no change or modest improvements in CGM metrics acutely during the initial strict COVID-19 lockdowns, few studies have examined longer-term trends, and none to our knowledge out to 2 years. That being said, one study from the Netherlands reported HbA1c levels and CGM metrics in 437 individuals with type 1 diabetes pre-pandemic and 1-year after lockdown, reporting a 0.4% reduction in HbA1c [from 7.9% (62.8 mmol/mol) to 7.5% (58.5 mmol/mol)], with an associated increase in TIR and decrease in TBR [37]. In that study, participants with type 1 diabetes were older (average age approx. 48 years), with lower HbA1c levels [mean HbA1c approx. 7.9% (62.8 mmol/mol)] and with approximately 83.5% of the study participants already using isCGM or rtCGM. In the present study, we similarly observed a 0.4% (4.1 mmol/mol) reduction in HbA1c in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes, whose baseline HbA1c was higher (8.5 ± 1.7%; 69.3 ± 18.8 mmol/mol) and with lower use of diabetes technologies before the pandemic. Furthermore, when we explored the change in laboratory HbA1c from pre-pandemic levels, we observed that this was most apparent in the second year after the pandemic was declared; and that reduction in HbA1c occurred primarily in patients who had had sustained contact with the clinic compared to those who reconnected for the first time after a period of absence. We have previously reported on the glycemic control of the emerging adults attending the Young Adult Diabetes Clinic at St. Michael’s Hospital [22], where, during the period 2011–2016, the mean HbA1c remained unchanged at 8.9% (73.8 mmol/mol) [22]. The pre-pandemic HbA1c of 8.5% (69.3 mmol/mol) in this clinic population herein reported indicates that glycated hemoglobin levels were already falling from their historical average prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In our review of the management of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes, we also observed notable changes in the use of diabetes technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic. In January 2018, the province of Ontario introduced its OHIP+ program which covers the costs of drugs and some devices for those up to and including the age of 24 years and, in September 2019, use of the Freestyle Libre was covered under this plan. With widespread availability of isCGM at no cost to the user, and with the later coverage of the Freestyle Libre 2 with its high- and low-glucose alerts, there was a shift in glucose monitoring methodology used by emerging adults from predominantly SMBG to isCGM. Together with cloud-based glucose monitoring, this has allowed healthcare providers remote access to multiple indicators of glucose control quality through the ambulatory glucose profile (AGP). Although isCGM and remote monitoring enhance glucose insights, in this cohort of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes the transition from predominant SMBG use to predominant isCGM use was not associated with an overall improvement in glycated hemoglobin among isCGM users. In previous qualitative interviews with patients at the Young Adult Diabetes Clinic at St. Michael’s Hospital approximately 57% of participants provided narratives that were characterized by being burdened by diabetes or making efforts to minimize the impact of diabetes on their daily lives [19]. In the present study, at the end of the follow-up period, 83% of emerging adults for whom data were available were wearing a glucose-sensing device. Indeed, even among those with an HbA1c ≥ 10% (86 mmol/mol), suggestive of challenges with diabetes self-management, 9 of 11 (82%) emerging adults were using a CGM at the end of the study (8 (73%) isCGM, 1 (9%) rtCGM). Thus, despite the challenges this population may face in achieving their self-management goals, when financial barriers to access are removed, there is widespread uptake of glucose-sensing technology.

Although there was a shift in glucose monitoring methodology from SMBG to CGM in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic, the improvement in HbA1c that was observed in this cohort was primarily seen in those using rtCGM. Several factors may account for this. Firstly, in November 2020, Control-IQ hybrid closed loop technology, which adjusts basal insulin delivery according to CGM and delivered insulin data, received regulatory approval by Health Canada. Control-IQ runs on the Tandem t:slim X2 insulin pump and Dexcom G6 rtCGM. At the end of the review period, 17 patients were using both the Tandem t:slim X2 pump and Dexcom G6 rtCGM, providing them access to automated insulin delivery. Secondly, however, unlike isCGM, rtCGM is not covered by Ontario’s OHIP+ plan. ADP reimbursement for rtCGM in Ontario was introduced in March 2022, but it is extremely restrictive in its coverage. We are not aware of any evidence to indicate that the timing of decisions on device approvals was influenced by the challenges faced by people with diabetes during the pandemic. Thus, in Ontario rtCGM is primarily used by emerging adults with type 1 diabetes who have private health insurance or else the financial means to pay for the device independently. This illustrates a recurring theme that has emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, that those of higher socioeconomic status achieved better outcomes [8, 38].

Aside from changes in glycemic control and device usage, the present study also looked at clinic attendance patterns and healthcare provider interactions. Although there was initial concern that the abrupt change away from traditional in-person clinic visits would impact access to care, this is not borne out by attendance data. Over a follow-up period that averaged a little over 2 years, emerging adult patients had on average approximately 10 interactions with the diabetes care team, 80% of which were virtual. It is noteworthy, however, that because of the multidisciplinary nature of the clinic, more than one contact with a healthcare provider may have occurred on the same day and thus these contacts were not necessarily distributed evenly over the follow-up period. Nonetheless, loss to follow-up was relatively low (11.5%) which compares with a loss to follow-up rate we previously reported for this population of 21% between 2011 and 2016 [22]. That being said, fewer new patients were seen (in-person or virtually) during the COVID-19 pandemic (6 new patients and 6 returning from previous loss to follow-up) than had been seen in the prior year (21 patients). The causes of this reduction in new patient visits are multifactorial, including decisions not to transition patients from pediatric care early in the pandemic because of concerns about loss to follow-up risk and barriers to transitioning older emerging adults from the clinic exacerbated by healthcare worker shortages [2].

The strengths of the study include the prolonged duration of follow-up, the focus on the provision of care to emerging adults with type 1 diabetes during the pandemic, and the previous characterization of this clinic population [19, 20, 22]. Limitations include its retrospective, single-centre nature. Furthermore, because data were extracted from patient’s medical records, information is not available on insulin dosage, socioeconomic status, family support and lifestyle changes (physical activity, meal planning, sleep duration, remote work) during the pandemic. Likewise, because a body of literature already existed regarding CGM metric changes during lockdown, the study’s focus was on patterns of care, self-management and clinic attendance. Accordingly, we did not access cloud-based platforms and thus CGM data, which were derived from the patient’s medical record, are incomplete. Lastly, there are several emergency departments in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). For privacy reasons, we did not seek access to data on emergency room visits in the GTA and thus no information is available on rates of acute diabetes complications before and during the pandemic. Similarly, actual COVID-19 vaccination rates for this particular cohort were unavailable.

Conclusion

The findings of the present report are aligned with shorter-term predominantly CGM-based studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], now reporting that HbA1c levels have declined in an emerging adult population with type 1 diabetes 2 years into the COVID-19 pandemic, associated with increased use of wearable diabetes devices. Despite these ostensibly encouraging findings, caution should be exercised in that the findings may reflect benefits primarily seen in socioeconomically advantaged individuals and those who already had access to multidisciplinary care within a tertiary referral centre before the pandemic. Data are needed on longer-term glycemic control measurements for emerging adults with type 1 diabetes in lower- and middle-income countries. The findings of the present study do, however, support advocacy for wider access to rtCGM and the continued use of telemedicine as the pandemic (hopefully) continues to subside.

References

https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

https://www.cma.ca/news-releases-and-statements/canadas-health-system-life-support-health-workers-call-urgent. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

O’Mahoney LL, Highton PJ, Kudlek L, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on glycaemic control in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:1850–60.

Garofolo M, Aragona M, Rodia C, et al. Glycaemic control during the lockdown for COVID-19 in adults with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;180: 109066.

Di Dalmazi G, Maltoni G, Bongiorno C, et al. Comparison of the effects of lockdown due to COVID-19 on glucose patterns among children, adolescents, and adults with type 1 diabetes: CGM study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8: e001664.

Hakonen E, Varimo T, Tuomaala AK, Miettinen PJ, Pulkkinen MA. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on the glycemic control of children with type 1 diabetes. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:48.

Wu X, Luo S, Zheng X, et al. Glycemic control in children and teenagers with type 1 diabetes around lockdown for COVID-19: a continuous glucose monitoring-based observational study. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12:1708–17.

van der Linden J, Welsh JB, Hirsch IB, Garg SK. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and its impact on time in range. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23:S1–7.

Brener A, Mazor-Aronovitch K, Rachmiel M, et al. Lessons learned from the continuous glucose monitoring metrics in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes under COVID-19 lockdown. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57:1511–7.

Abdulhussein FS, Chesser H, Boscardin WJ, Gitelman SE, Wong JC. Youth with type 1 diabetes had improvement in continuous glucose monitoring metrics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23:684–91.

Nwosu BU, Al-Halbouni L, Parajuli S, Jasmin G, Zitek-Morrison E, Barton BA. COVID-19 pandemic and pediatric type 1 diabetes: no significant change in glycemic control during the pandemic lockdown of 2020. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 703905.

Choudhary P, Kao K, Dunn TC, Brandner L, Rayman G, Wilmot EG. Glycaemic measures for 8914 adult FreeStyle Libre users during routine care, segmented by age group and observed changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:1976–82.

Capaldo B, Annuzzi G, Creanza A, et al. Blood glucose control during lockdown for COVID-19: CGM metrics in Italian adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e88–9.

Prabhu Navis J, Leelarathna L, Mubita W, et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on flash and real-time glucose sensor users with type 1 diabetes in England. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58:231–7.

Longo M, Caruso P, Petrizzo M, et al. Glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes using a hybrid closed loop system and followed by telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;169: 108440.

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–80.

Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:971–8.

Peters A, Laffel L, American Diabetes Association Transitions Working Group. Diabetes care for emerging adults: recommendations for transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care systems: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, with representation by the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Osteopathic Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Children with Diabetes, The Endocrine Society, the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, the National Diabetes Education Program, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society (formerly Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society). Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2477–85.

Markowitz B, Pritlove C, Mukerji G, Lavery JV, Parsons JA, Advani A. The 3i conceptual framework for recognizing patient perspectives of type 1 diabetes during emerging adulthood. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2: e196944.

Pritlove C, Markowitz B, Mukerji G, Advani A, Parsons JA. Experiences and perspectives of the parents of emerging adults living with type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8: e001125.

Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21:66–72.

Markowitz B, Parsons JA, Advani A. Diabetes in emerging adulthood: transitions lost in translation. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41:1–5.

https://globalnews.ca/news/6672149/toronto-university-classes-coronavirus-covid-19/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

https://globalnews.ca/news/6688074/ontario-doug-ford-coronavirus-covid-19-march-17/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

https://www.toronto.ca/news/mayor-tory-declares-a-state-of-emergency-in-the-city-of-toronto/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/we-are-on-the-right-track-toronto-formally-ends-municipal-state-of-emergency-after-777-days-1.5894846. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109:531–8.

Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan. China JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:934–43.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62.

Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:813–22.

Andrikopoulos S, Johnson G. The Australian response to the COVID-19 pandemic and diabetes—lessons learned. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;165: 108246.

Ravert RD, Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Kim SY, Weisskirch RS, Bersamin M. Sensation seeking and danger invulnerability: paths to college student risk-taking. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47:763–8.

https://www.utoronto.ca/utogether/covid-19-planning-update. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

https://www.toronto.ca/news/toronto-is-a-global-leader-in-covid-19-vaccination-coverage/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

Verma A, Rajput R, Verma S, Balania VKB, Jangra B. Impact of lockdown in COVID 19 on glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:1213–6.

Hosomi Y, Munekawa C, Hashimoto Y, et al. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyle and glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetol Int. 2022;13:85–90.

Ali N, El Hamdaoui S, Nefs G, Tack CJ, De Galan BE. Improved glucometrics in people with type 1 diabetes 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2022;1010: e002789.

Im JHB, Escudero C, Zhang K, et al. Perceptions and correlates of distress due to the COVID-19 pandemic and stress management strategies among adults with diabetes: a mixed-methods study. Can J Diabetes. 2022;46:253–61.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the excellent care provided to the patients of the Young Adult Diabetes Clinic at St. Michael’s Hospital by Jane Mason, Megan Skinner, Nicole Pacheco and Victoria Lane, as well as the clinic administrative and clerical staff and the patients themselves.

Funding

These studies were funded by the RDV Foundation including the study and rapid service fee. A.A. holds the Keenan Chair in Medicine from St. Michael’s Hospital and University of Toronto.

Author Contributions

H.S. performed the primary extraction and collation of the data. A.A. conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Disclosures

Harshpreet Swaich and Andrew Advani have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the Unity Health Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB# 22-123), and it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent for the retrospective review was waived.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the nature of the study is such that participants were not asked to consent for patient level data to be shared publicly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swaich, H., Advani, A. Sustained Improvement in Glycemic Control in Emerging Adults with Type 1 Diabetes 2 Years After the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Diabetes Ther 14, 153–165 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-022-01346-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-022-01346-5