Abstract

Introduction

Despite the availability of sophisticated devices and suitable recommendations on how to best perform insulin injections, lipohypertrophy (LH) and bruising (BR) frequently occur as a consequence of improper injection technique.

Aim

The purpose of this nationwide survey was to check literature-reported LH risk factors or consequences for any association with BR

Method

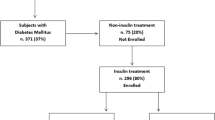

This was a cross-sectional, observational, multicenter study based on the identification of skin lesions at all patient-reported insulin injection sites in 790 subjects with diabetes. General and injection habit-related elements were investigated as possible BR risk factors.

Results

While confirming the close relationship existing between LH and a full series of factors including missed injection site rotation, needle reuse, long-standing insulin treatment, frequent hypoglycemic events (hypos), and great glycemic variability (GV), the observed data could find no such association with BR, which anyhow came with high HbA1c levels, missed injection site rotation, and long-standing insulin treatment.

Conclusion

BR most likely depends on the patient’s habit of pressing the injection pen hard onto the skin. Despite being worrisome and affecting quality of life, BR seems to represent a preliminary stage of LH but does not affect the rate of hypos and GV.

Trial Registration

207/19.09.2017

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bruising (BR) is a poorly investigated skin complication of improper insulin injection habits |

BR is often associated with lipohypertrophy (LH) at the injection sites, but can also occur separately |

BR does not correlate with factors associated with LH and does not modify the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of insulin; therefore, BR is not associated with the rate of hypoglycemic events and the extent of glycemic variability |

BR most likely depends on a hard pen pressure onto the skin, a habit commonly observed in people made insecure by unconscious injection fear |

BR is the consequence of an injection technique error and may represent an early stage of LH, thus requiring a more effective prevention through sustained structured education |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and video abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13721731

Introduction

Since the first patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) were provided with a syringe specifically designed for insulin treatment in 1924, subcutaneous insulin delivery options have changed from glass to disposable plastic syringes through to insulin pens and pen needles (PNs), and insulin pumps. Pens are now available for several insulin preparations owing to the ease, convenience, and accuracy of drug delivery [1, 2]. For the last decade or so, thanks to technological advances, have pens become more and more accurate and user-friendly while progressively shorter and sharper needles have made injections easier and better accepted by patients [3].

However, despite the availability of sophisticated devices and suitable recommendations on proper injection techniques [4, 5], current literature reports a high rate of injection errors responsible for lipodystrophy (LD) [6] and consequent metabolic disorders [7, 8] by referring to different care settings and most often providing little information on lipohypertrophy (LH) identification methods [9,10,11].

All Italian citizens, irrespective of social class or income, are assisted by a general practitioner (GP) participating in the National Health System (NHS). As an estimate, over 3 million citizens have known diabetes in Italy [12]. They are assisted by a public network consisting of about 700 diabetes clinics, ensuring diagnosis confirmation, treatment, prevention, and early complication detection thanks to a strict, free, follow-up program performed by diabetes care teams (DCTs) at regular intervals. Most patients are referred to such care units by their GPs [13, 14], who, in the case of persistent hyperglycemia or fast-progressing chronic complications [15], preferentially ask DCTs to start patients on insulin and educate them on appropriate injection techniques [6]. Despite such a complex three-level care organization and the opportunities offered by technological advances, LD still frequently occurs because of improper insulin injection technique.

The purpose of this survey was to check literature-reported LH-related factors or consequences for any association with bruising. To do so, for the first time, we chose a single care setting, i.e., the diabetes care unit (DCU), and focused only on pen-using insulin-treated adults on multiple daily injections (MDI) in order to prevent any treatment inhomogeneity-related biases.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, observational, multicenter study based on the identification of skin lesions at all patient-reported insulin injection sites. Sixteen certified DCUs adhering to the continuous Association of Clinical Diabetologists (AMD) quality-of-care improvement program [13] participated in the study after declaring their willingness and ability to select at least 20 patients. The average number of consecutive recruited people with diabetes was 60 ± 27 per center (median value 42; maximum 167), summing up to 780 outpatients, whose main features are reported in Table 1.

Inclusion Criteria

The study included any pen-using patients with DM at least 18 years of age consecutively referring to the DCUs having been on at least two insulin injections per day for 1 year. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant agent utilization was no reason for exclusion.

Exclusion Criteria

The study excluded patients with neoplastic disease, liver or kidney advanced disease, steroid-based treatment, and pregnancy.

Study Protocol

The protocol was designed according to the original Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments, and approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Coordinator Centre, “Vanvitelli” University Hospital of Naples, Italy (protocol number 207/19.09.2017, and by the institutional review board (IRB Min No. 8726 dated 09.11.2017).

All patients provided informed consent for the use of personal data for study purposes. Each patient completed a questionnaire previously utilized by several groups [6, 16, 17], including ours [18], which also let specifically trained nurses know individual injection sites, where skin lesions were then looked for, according to a structured protocol.

The following data were recorded: demographics, diabetes duration, insulin type, and therapeutic scheme daily dose, number of injections per day, type of needle (length and gauge), needle reuse, injection site rotation, ice-cold insulin injections [6], distance between injection sites (centimeters), intra-LH injections, rate of unexplained hypoglycemia (hypo), blood glucose variability (GV).

Hypo was defined as the occurrence of one or more symptoms of hypoglycemia (such as palpitations, tiredness, sweating, hunger, dizziness, and tremor) and a confirmed blood glucose meter reading of 60 mg/dL or less, as previously described several times [9,10,11, 18]. Frequent unexplained hypo was defined as having one or more hypos a week in the absence of any changes in medication, diet, or physical activity [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In the absence of any universally accepted definition, in our study, GV was classified as unpredictable and unexplained self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG)-based glucose oscillations ranging from less than 60 to more than 250 mg/dL at least three times a week for at least 6 months [18,19,20].

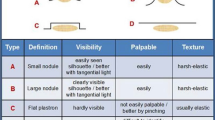

Identification of Skin Area of Interest Training Protocol

The validated LH identification method was described previously [9, 11, 18]. It consisted of inspecting each area of interest through direct and tangential light against a dark background and a thorough palpation technique implying slow circular and vertical fingertip movements followed by repeated horizontal attempts on the same spot. Healthcare professionals had to touch the skin gently initially and progressively increase finger pressure. They also confirmed the clinical diagnosis through a pinching maneuver to distinguish contiguous areas by thickness and hardness. When needed, smaller and flatter lesions were further identified by ultrasound (US) scanning, as previously described [18]. Expert team physicians identified bruising during the systematic injection site inspection.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and discrete variables as the absolute frequency with percentage. Data entered a mixed logistic regression model with DCUs fitted as random to rule out any possible differences across centers among the rest while including outcome-associated variables showing a p < 0.10 at univariate analysis. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Analyses were performed using STATA software, version 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas); p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

As shown in Table 1, 780 patients (49.6% male) were enrolled, 224 of which had type 1 DM (T1DM) and the others had type 2 DM (T2DM), with the following features: age 62 ± 15 years, BMI 29 ± 6 kg/m2, disease duration 18 ± 11 years, daily insulin dose 46 ± 26 IU, and daily insulin injections 3.7 ± 2.6. Overall 86.0% subjects used basal insulin analogues, 93.5% fast-acting analogues, 7.3% premixed insulins, 0.9% regular human insulin, and 0.6% NPH; 92.1% of patients self-injected insulin, 22.8% repeatedly reused (2.4 ± 0.8 times), 34.7% failed to rotate injection sites, and 14.7% injected ice-cold insulin.

As seen in Table 1, 73.4% of patients had been using pens for 1–9 years, 10.6% patients for less than 1 year and 16% for over 9 years. They mostly used 5- and 4-mm needles (30.6% and 28.5%, respectively), with 20.0% using the 6-mm needles and 20.6% using 8-mm ones; only eight subjects used 12.7-mm needles (Fig. 1a). Over 50% of patients used 31G needles, 31.4% used 32G needles, and the rest, i.e., very few, different gauges (Fig. 1b).

Overall 46.2% subjects had LH lesions with a 4.8 ± 3.1 cm mean. Lipoatrophic (LA) skin lesions were quite uncommon (3.2%), while bruising (BR) occurred in 33.2% cases, either associated with LH lesions (n = 178; 53.9%) or without LH (n = 156; 46.6%). Forty-nine out of 156 BR-affected patients were on antiplatelet agents; none were taking anticoagulants. All patients declared that BRs had been present for a long time at injection sites and they preferred those sites despite BRs, due to the following reasons: (i) injection into those areas was painless (53%); (ii) they had seen other patients doing the same (21%); (iii) they went on like this by habit or because of laziness (26%). Bruising was not present in skin areas other than those used for insulin injection.

Overall 32.2% of subjects had LH at only one site, and 65.8% of patients had LH at several site levels, primarily the abdomen (52.4%), followed by thighs (23.2%), arms (19.9%), and other unusual areas (4.5%), including the thigh area located immediately distal to the crural region, the areas immediately above the knee, and the proximal arm region (34.2%); 69.2% of those with LH systematically injected insulin into the nodules.

Table 2 shows the univariate analysis of all parameters under investigation on the basis of LH presence. LH was associated with T2DM (about a third only having T1DM), higher HbA1c levels, longer disease or insulin treatment duration, and higher daily insulin doses. Other factors associated with LH lesions were basal analogue utilization, high hypo rate, large GV, needle reuse, missed injection site rotation, and longer (6, 8, and 12.7 mm) and larger-gauge (31G) needles.

Multivariate analysis (Table 3) confirmed the following parameters to be significantly associated with LH: high hypo rate, large GV, failure to rotate injection sites, and an over-9-year insulin treatment duration.

To investigate BR’s relationship with the LH-associated parameters in the absence of confounding factors, we separately analyzed subjects having BR only or LH only (Table 4), thus showing a significant association between BR and high HbA1c levels, missed injection site rotation, and long-standing insulin treatment.

Patients with BR were mainly female, older people with T2DM, and with a higher BMI; their HbA1c levels were equal to those from LH-affected ones (7.9 ± 1.3%) but higher than those from people with healthy skin (7.9 ± 1.3 vs. 7.6 ± 0.9%; p < 0.05).

Surprisingly, BR-affected patients had a lower hypo rate and a less prominent GV than those with LH. They were quite similar to people with LH, instead, in terms of missing site rotation, self-injection, needle reuse, and basal analogue utilization, yet significantly fewer of them had a longer than 9-year treatment duration. Interestingly, only one-third of subjects with BR was on salicylate or other antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants (of 156 subjects, 48 used salicylate and 1 anticoagulant agents).

Discussion

LD is a common complication of subcutaneous insulin injection and may present as either LH or LA. Although the exact etiology of LH is unclear, various local injection-related factors appear to be at play, such as insulin itself with its strong growth-promoting properties, repeated trauma to the same site when patients fail to rotate injections, and needle reuse [3, 6, 18, 21].

In contrast, LA is a scarring lesion due to subcutaneous fatty tissue atrophy, likely because of an immune reaction. Indeed, LA is more frequent in patients with T1DM, presents mast cells and eosinophils at biopsy, and displays positive responses to mast-cell inhibiting treatment [6, 22]. A lipolytic reaction occurs, probably depending on impurities or other insulin preparation components, in LA lesions, which, indeed, have become less prevalent as products are more refined and now affect only 1–2% of insulin-treated patients [6, 22].

LH detection requires both inspection and palpation of injecting sites according to a structured procedure [18, 21], as some lesions can be more easily felt than seen [9, 11, 23]. Both pen and syringe devices (and all needle lengths and gauges) have been associated with them, as insulin pump cannulae repeatedly inserted into the same skin area also have [2, 7, 24,25,26].

Many literature reports describe a variable rate of LD, under different settings, like adult outpatients treated by primary care physicians and others referring to diabetes centers or even children. Most of them provide little information on identification methods [9,10,11].

Ours is the first investigation on LDs performed in a homogeneous series of adult outpatients using the same injection system randomly enrolled in a unique care setting represented by 16 specialized units for diabetes. In a previous paper, some differences were found by comparing generalist- to specialist-related observations [6], but, different from that, by multivariate analysis, our data confirmed only the strong relationship between LH and poor metabolic control, high hypo rates, large GV, missing site rotation, and insulin treatment duration. The real surprise was the lack of previously reported (Blanco) association between needle reuse and LH presence. Nevertheless, such a result might depend on needle-reusing subjects representing only 22.8% of the entire series and that the frequency of needle reuse was low anyhow (2.4 ± 0.8 times). Also, the minimal number of LA lesions is most likely due to a limited use of old (regular or human NPH) insulins.

Another original aspect of this paper was the first clinical evaluation made of skin bruising at the injection sites (Figs. 2 and 3).

Bruising is mentioned in several studies [27, 28]. It is a rather disturbing insulin injection side effect due to the resulting blemishes, for which no solutions have been identified as yet. Unfortunately, in terms of both patient and healthcare provider perspectives, injection-related problems negatively affect the overall number of shots that patients with diabetes are willing to take, so that in some studies half of the patients reported mentioning such problems to their healthcare providers without getting any solution against the associated pain and bruising [6, 16, 17]. Concerning that, site-related adverse events, including pain, redness, bleeding, and, especially, bruising, are significant barriers to patient adherence to multiple daily injection regimens. This is particularly important when physicians and/or healthcare providers have insufficient experience or knowledge about specific assistance [6, 10], or when the doctor–patient relationship is unsatisfactory [6, 10].

To fill this gap, during the last few years, an interesting exchange of experiences started among patients through various networks, including the American Diabetes Association Community first [29]. Such forums enabled patients to propose several attractive solutions themselves, including a sufficiently long injection time, thin and short needles, and a careful injection site rotation protocol. However, specific investigations are still warranted to assess the reasons behind the aforementioned injection complications and to identify scientifically sound solutions aimed to improve patient adherence to insulin therapy.

In our study, BR was associated with poor metabolic control as was LH, but not GV and hypo risk. The interpretation of this data is difficult and does not seem to be influenced by antiplatelet or anticoagulant agent utilization, which involved only a minority of patients (12% in patients with bruising and 14% in patients without bruising) or appear to be related to coagulation-affecting diseases, like cirrhosis and severe kidney disease, which had been excluded.

Interestingly, we noticed that many patients do not handle pens correctly while injecting insulin, by often using both hands or failing to complete the injection fully. They most often press the pen onto the skin too hard so that the needle-cone injuries the site (Fig. 4). This occurred primarily in our older patients having hand joint problems or feeling insecure for fear of the injection. Such anecdotal observations need verification, through dedicated studies.

The association between BR and high HbA1c levels, missed injection site rotation, and long-standing insulin treatment likely reflects inadequate patient education. The significantly lower number of patients with BR than with LH who reported insulin treatment longer than 9 years could depend on the fact that the injury behind BR, despite being caused by repeated micro-traumas like LH, may be an early step of LH formation which does not cause tissue hypertrophy and so does not cause insulin pharmacokinetic alterations. Such a hypothesis deserves extensive investigation.

Limitations

A major limitation of our study is that clinical explanations for BR are largely hypothetical. However, the newest and most relevant finding is that BR does not influence hypo rate and GV significantly, opposite to what is seen with LH.

Conclusion

This study was conducted in a specialized setting and using strict methodology to confirm that missing site rotation and needle reuse are significant risk factors for LH. The close relationship between LH and poor metabolic control could suggest that all patients with clear-cut difficulties in achieving optimal control should be checked systematically for LH presence at all insulin injection sites. The same applies to those who experience frequent unexplained hypos or large GV.

References

Stocki K, Ory C, Vanderplas A, et al. An evaluation of patient preference for an alternative insulin delivery system compared to standard vial and syringe. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:133–46.

Rosak C, Burkard G, Hoffmann JA, et al. Metabolic effect and acceptance of an insulin pen treatment in 20,262 diabetic patients. Diab Nutr Metab. 1993;6:139–45.

Hansen B, Matytsina I. Insulin administration: selecting the appropriate needle and individualizing the injection technique. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8(10):1395–406.

Frid AH, Hirsch LJ, Menchior AR, Morel DR, Strauss KW. Worldwide injection technique questionnaire study: injecting complications and the role of the professional. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1224–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.012.

Gentile S, Grassi G, Armentano V, et al. AMD-OSDI consensus on injection techniques for people with diabetes mellitus. Med Clin Rev. 2016;2:3. http://medical-clinical-reviews.imedpub.com/archive.php. Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Blanco M, Hernández MT, Strauss KW, Amaya M. Prevalence and risk factors of lipohypertrophy in insulin-injecting patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(5):445–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2013.05.006.

Saltiel-Berzin R, Cypress M, Gibney M. Translating the research in insulin injection technique: implications for practice. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(5):635–43.

Young RJ, Hannan WJ, Frier BM, Steel JM, Duncan LJ. Diabetic lipohypertrophy delays insulin absorption. Diabetes Care. 1984;7:479–80.

Gentile S, Guarino G, Giancaterini A, Guida P, Strollo F, AMD-OSDI Italian Injection Technique Study Group. A suitable palpation technique allows to identify skin lipohypertrophic lesions in insulin-treated people with diabetes. Springerplus. 2016;5:563. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1978-y.

Gentile S, Strollo F, Guarino G. Why are so huge differences reported in the occurrence rate of skin lipohypertrophy? Does it depend on method defects or on lack of interest? Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(1):682–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.11.042.

Gentile S, Strollo F, Guarino G, et al. Factors hindering correct identification of unapparent lipohypertrophy. J Diabetes Metab Disord Control. 2016;3(2):42–7. https://doi.org/10.15406/jdmdc.2016.03.00065.

Il Diabete in Italia Anni 2000–2011. Istat 2012 http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/71090. Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Nicolucci A, Rossi MC, Arcangeli A, et al. Four-year impact of a continuous quality improvement effort implemented by a network of diabetes outpatient clinics: the AMD-Annals initiative. Diabet Med. 2010;27:1041–8.

Nicolucci A, Rossi MC, Arcangeli A, et al. Four-year impact of a continuous quality improvement effort implemented by a network of diabetes outpatient clinics: the AMD-Annals initiative. Diab Med. 2010;27(9):1041–8.

Strollo F, Guarino G, Marino G, Paolisso G, Gentile S. Different prevalence of metabolic control and chronic complication rate according to the time of referral to a diabetes care unit in the elederly. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51(3):447–53.

Strauss K, Gols D, Hannet I, Partanen M, Frid A. A pan-European epidemiologic study of insulin injection technique in patients with diabetes. Pract Diab Int. 2002;19(3):71–6.

De Coninck C, Frid A, Gaspar R, et al. Results and analysis of the 2008–2009 Insulin Injection Technique Questionnaire survey. J Diabetes. 2010;2(3):168–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00077.x.

Gentile S, Guarino G, Corte TD, et al. Insulin-induced skin lipohypertrophy in type 2 diabetes: a multicenter regional survey in Southern Italy. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(9):2001–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00876-0.

Ampudia-Blasco FJ. Postprandial hyperglycaemia and glycemic variability: new targets in diabetes management. Av Diabetol. 2010;26:S29-34.

Hirsch IB, Bode BW, Childs BP, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) in insulin- and non-insulin-using adults with diabetes: consensus recommendations for improving SMBG accuracy, utilization, and research. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008;10:419–39.

Gentile S, Guarino G, Della Corte T. Lipohypertrophy in elderly insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12(1):107–19.

Bohannon NJV, Ohannesian JP, Burdan AL, et al. Patient and physician satisfaction with the Humulin/Humalog pen, a new 3.0-mL prefilled pen devicefor insulin delivery. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1049–67.

Tandon N, Kalra S, Balhara YP, et al. Forum for Injection Technique (FIT), India: the Indian recommendations 2.0, for best practice in Insulin Injection Technique, 2015. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(3):317–31. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.152762.

Chowdhury TA, Escudier V. Poor glycaemic control caused by insulin induced lipohypertrophy. Br Med J. 2003;327:383–4.

Famulla S, Hövelmann U, Fischer A, et al. Insulin injection into lipohypertrophic tissue: blunted and more variable insulin absorption and action and impaired postprandial glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(9):1486–92. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0610.

Partanen T, Rissanen A. Insulin injection practices. Pract Diab Int. 2000;17:252–4.

Gentile S, Strollo F, Ceriello A, AMD-OSDI Injection Technique Study Group. Lipodystrophy in insulin-treated subjects and other injection-site skin reactions: are we sure everything is clear? Diabetes Ther. 2016;7(3):401–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-016-0187-6.

McNally P, Jowet N, Kurinczuk J, Peck R, Hearnshaw J. Lipohypertrophy and lipoatrophy complicating treatment with highly purified bovine and porcine insulin. Postgrad Med. 1988;64:850–3.

ADA Community. Adults living with type 2. http://community.diabetes.org/t5/Adults-Living-with-Type-2/Bruising-at-Injection-Sites/td-p/226433. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to Paola Murano from Nefrocenter Research Network, for her complimentary editorial assistance, and to Members of the AMD-OSDI Study Group on Injection Technique for critical reading and approval of the manuscript. We also feel deeply indebted to all patients for contributing to the study by giving informed consent to their data and pictures' anonymized utilization.

AMD-OSDI Study Group on injection technique: Advisory board: Sandro Gentile, Felice Strollo, Giuseppina Guarino. Scientific Committee: Vincenzo Armentano, Lia Cucco, Nicoletta De-Rosa, Luigi Gentile, Sandro Gentile, Annalisa Giancaterini, Giorgio Grassi, Carlo Lalli, Giovanni Lo-Grasso, Maurizio Sudano, Patrizio Tatti.

Researchers (Doctors and Nurses: Angioni A, Armentano V, Ballauri C, Botta A, Bova A, Calzolari G, Canu L, Capuano G, Caraffa F, Cavani R, Cavuto L, Cimitan F, Ciotola M, Clemente G, Colarusso S, Corsini R, Cristofanelli L, Cucco L, Del Buono A, De Rosa N, Di Blasi V, Di Levrano G, Di Loreto C, Felace G, Fiorentino R, Focardi M, Gaeta I, Gaiofatto R, Garrapa G, Gentile L, Guarino G, Guida D, Lai M, Lalli C, Landini C, Lucia E, Maino S, Manfrini S, Marcone ATM, Marino C, Marino G, Mazzocchi L, Merlini A, Miranda C, Moscatelli C, Musto B, Oliva D, Oliviero B, Pasquero A, Piastrella L, Pisanu P, Pollace M, Raffaele A, Ravera M, Russo E, Scarpitta A, Speese K, Strollo F, Sudano M, Tommasi E, Tonutti L, Turco S, Uberti M, Viberti P, Vinci C, Zambroni M, Zamparo F, Zenoni L, Zoffoli M. Nefrocenter Research & Nyx Start-up Study Group on diabetes:

Diabetologists: Sandro Gentile, Giuseppina Guarino, Felice Strollo, Gerardo Corigliano, Marco Corigliano, Maria Rosaria Improta, Carmine Martino, Antonio Fasolino, Antonio Vetrano, Agostino Vecchiato, Domenica Oliva, Clelia Lamberti, Domenico Cozzolino, Clementina Brancario, Luca Franco. The complete list of Nefrocenter Research & Nyx Start-up Study Group is available on https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12555584.

Funding

The paper was supported by a non-conditioning special grant of Nefrocenter Research Network and NYX Start-up, Naples, Italy. None of the authors or co-workers received funding for the publication of this study and the Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published: Sandro Gentile, Giuseppina Guarino, Teresa Della Corte, Giamiero Marino, Ersilia Satta, Carmine Romano, Carmelo Alfarone, Clelia lamberti and Felice Strollo.

Authorship Contributions

Sandro Gentile and and Felice Strollo prepared and wrote the paper. Teresa Della Corte and Giuseppina Guarino critically read and approved the paper. All complied with data collection, critically assessed the results, and approved the final text. In addition to contributing to the collection of data like the other members of the Nefrocenter Study Group, CL has been irreplaceable in the work of reviewing the paper and in the responses to reviewers. All Researchers and Collaborators critically read and approved the final text.

Disclosures

Sandro Gentile, Giuseppina Guarino, Teresa Della Corte, Giamiero Marino, Ersilia Satta, Carmine Romano, Carmelo Alfarone, Clelia Lamberti and Felice Strollo have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in conformance with good clinical practice standards. The study was led in accordance with the original Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Vanvitelli University, Naples, Italy (Trial registration no. 207/19.09.2017), approved by the Scientific and Ethics Committee of Campania University “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Naples, Italy, and by the institutional review board (IRB Min No. 8726 dated 09.11.2017), which served as the central reference ethics committee for all involved diabetes centers, the latter being an integral part of the same private consortium associated to the aforementioned university. Before enrollment, all involved patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study and have their data and pictures anonymously used for publication.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The members of the AMD-OSDI Study Group are mentioned in the Acknowledgments section.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gentile, S., Guarino, G., Della Corte, T. et al. Bruising: A Neglected, Though Patient-Relevant Complication of Insulin Injections Coming to Light from a Real-Life Nationwide Survey. Diabetes Ther 12, 1143–1157 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-021-01026-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-021-01026-w