Abstract

Climate change is expected to cause an increased frequency of extreme events such as heavy floods and major storms. Such stochastic events have an immediate impact on surface water quality, but the long-term effects are largely unknown. In this study, we assess long-term monitoring data from two Swedish headwater catchments affected by extreme weather events. At one site, where nitrogen effects in soil water, groundwater, and stream water were studied after storm-felling and subsequent forest dieback from bark beetle attack, long-term (>5 years) but relatively modest (generally <1 mg L−1) increases in ammonium (NH4-N) and nitrate (NO3-N) concentrations were observed in the various aqueous media. At the other site, where effects on benthic fauna were studied in a stream impacted by extreme geophysical disturbances caused by rainstorm-induced flashflood, only short-term (1 year) effects were revealed both regarding diversity and composition of species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Climate change is predicted to increase air temperature by 2–5 °C and precipitation by 9–17 % in the Baltic region by the end of twenty-first century (BACC 2008). Increased frequencies of extreme events such as heavy floods, long droughts, or major hurricanes are also expected according to IPCC (2012). Such stochastic events may have an immediate effect on the boreal landscape as well as long-lasting cascading impacts coupled with succeeding insect- and fungi-induced tree mortality, affecting biogeophysical and biogeochemical processes both in terrestrial and aquatic environments (Edburg et al. 2012; Mikkelson et al. 2013).

Natural disturbances such as storm felling and bark beetle outbreaks have similarities with tree harvesting. A diminished forest canopy reduces water and nutrient uptakes by the vegetation, creating prerequisites for increased element leakage to streams. However, a typical bark beetle outbreak after massive storm felling lasts for about 3–5 years and mainly affects mature trees (Schroeder and Lindelöw 2002; Grodzki et al. 2006; Långström et al. 2009), while final felling is more or less instantaneous and also includes cutting of young trees. The prolonged and initially scattered canopy removal in bark beetle-infested stands results in less stark changes in the biogeochemistry compared with final felling due to compensatory capacity associated with undisturbed residual vegetation and soils (Tahovská et al. 2010; Griffin et al. 2013; Kaňa et al. 2013; Rhoades et al. 2013). However, bark beetle-induced forest dieback may tangibly affect the surface water concentrations of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and acidity-related elements such as base cations and aluminum (Mikkelson et al. 2013; Oulehle et al. 2013; Vrba et al. 2014).

Following bark beetle attacks, N-limited catchments in North America generally showed small effects on the nitrate (NO3 −) response in both soil and surface waters, while N-rich catchments in Central Europe and Asia exhibited much larger responses (Huber 2005; Mikkelson et al. 2013). Ammonium (NH4 +) concentrations in soil water (SW) showed a more profound, universal increasing trend. Depending on residual vegetation, regrowth, N turnover, hydrologic flow paths, etc., it is possible that the N concentrations in surface waters will remain unaffected by bark beetle outbreaks (Mikkelson et al. 2013).

Besides biogeochemical effects, natural disturbances play a major role in structuring most ecological communities by redistribution of available resources. In lotic systems, hydrologic events such as floods accompanied by streambed and thus substratum movement are pervasive in forming benthic assemblages (e.g., Resh et al. 1988; Poff 1992; Townsend et al. 1997). Hydrologic disturbances can have different impacts on stream biota, depending on their intensity and frequency as well as dynamics (Lake 2000, 2003), timing and duration (Peterson and Stevenson 1992) and are influenced by e.g., structural heterogeneity (e.g., Hart and Finelli 1999; Boix et al. 2010), and channel morphology (Lake 2007). Hydrologic disturbances therefore act as environmental filters forcing a high selection pressure on stream biota (Poff 1997), and species must have certain adaptations supporting their resistance and resilience to persist in frequently disturbed streams. Species possessing these adaptations are likely to dominate communities (Death and Winterbourn 1994), especially in frequently disturbed, unstable, albeit predictable environments rapidly colonizing post-event habitats and recovering to pre-event densities (Fritz and Dodds 2004).

In this study, we have assessed the impacts of stochastic weather events by using long-term monitoring data from two Swedish headwater streams (Fig. 1a) affected by a hurricane and a rainstorm, respectively. Both events occurred at sites with seminatural headwater catchments in protected areas with unmanaged forests.

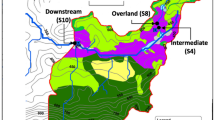

a Map showing the locations of Mount Fulufjäll (Stora Göljån stream) and Aneboda IM. b Generalized map of the Aneboda catchment showing the approximate location of the sampling stations. Red line catchment water divide; blue line stream; orange area or line with circles litterfall; purple area or line with diamonds throughfall; dark green area soil sampling plot; brown area vegetation plot; blue squares or line with squares GW sampling; pink cross or line with cross soil water sampling; green rings circular plots for monitoring tree layer, needle chemistry, algae, and lichen cover on needles; yellow arrow hydrology and water chemistry in catchment outlet. Contours at 2-m intervals. c Generalized map of the Stora Göljån and Lilla Göljån catchments showing the approximate location of the stream water and benthic invertebrate sampling stations. Red line catchment water divide; blue line stream. Contours at 20-m intervals. Background map: © Lantmäteriet, i2012/901

In January 2005, the integrated monitoring (IM) site at Aneboda was hit by the storm Gudrun. Most of the mature Norway spruce trees (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) were either storm felled or killed by the succeeding bark beetle (Ips typographus L.) outbreak. In August 1997, a rainstorm hit Mount Fulufjäll, and the resulting flashflood in the stream Stora Göljån completely changed the streambed geomorphology and uprooted trees and other vegetation along broad riparian strips (Figs. 2, 3). This was followed by attacks of bark- and wood-boring beetles, killing standing trees along the riparian forest edge. At both Aneboda and Stora Göljån, salvage felling did not occur, and the dead vegetation was left at site.

We have used monitoring data to investigate the impacts of (i) storm felling and extensive bark beetle-induced forest dieback on the N concentrations in SW, groundwater (GW), and stream water at Aneboda IM and; and (ii) a flashflood, and subsequently strong geomorphologic disturbance on benthic macroinvertebrates and their recovery patterns in Stora Göljån by tracking the temporal changes in assemblage composition structure and certain metrics (i.e., diversity, abundance, taxa richness) during the years before and after the event at Mount Fulufjäll. We predicted (i) strong and long-term effects on benthic macroinvertebrates in Stora Göljån due to the extreme geophysical disturbance, and (ii) no effects on the N concentrations in the Aneboda IM stream with low pre-event N-concentrations.

Study areas and weather events

Aneboda IM

Aneboda IM is a small (18.9 ha) forested catchment located above the highest marine coastline (210–240 m a.s.l.) in south central Sweden (Fig. 1b) and one of four Swedish IM sites. In Starr (2011), detailed descriptions of the catchments, methods, and results from the IM sites are presented. At Aneboda IM, the average atmospheric deposition of N on open field is around 7.5 kg ha−1 year−1, but as only one third of that averagely is present in throughfall (Table 1), it indicates a N-limited forest ecosystem. Before the catastrophic storm in 2005, nonmanaged, multi-aged Norway spruce covered 73 % of the catchment.

During January 8–9, 2005, southern Sweden was hit by a major storm named Gudrun. Wind speeds peaking at 42 m s−1 were registered on the Swedish west coast (Anonymous 2006). At the inland, a peak wind speed of 33 m s−1 was recorded at the meteorological station at the city of Växjö, located 30 km south of Aneboda IM, where maximum wind speeds >20 m s−1 were recorded over 9 h (unpublished data). Denmark, the Baltic states, and Russia were also affected, but to a much lower extent (Haanpää et al. 2006).

In Sweden, approximately 75 million m3 (stem volume over bark) of trees were felled during this night, corresponding to twice the normal annual cut in the affected area (Valinger and Fridman 2011). About 272 000 ha of forest was severely affected by the storm. The most devastating storm felling occurred in south-central Sweden, where a volume of 65–75 m3 ha−1 was damaged (Anonymous 2006). The highest impact was on mature even-aged Norway spruce stands (Anonymous 2006). In the Aneboda IM catchment, about 15–20 % of the trees were felled by the storm. However, the downed Norway spruce attracted bark beetles (Ips typographus L.), which caused a massive outbreak where the beetles infested a major part of the Norway spruce trees that survived the storm (Fig. 4). The quantitative effects of the storm felling and bark beetle infestation on the tree layer are assessed below.

The intensive vegetation plot no 1 at Aneboda IM viewed from the northwest corner in the middle of August in 2004 (upper left), 2007 (upper right), 2010 (lower left), and 2013 (lower right). The major storm Gudrun hit the area in January 2005, and the bark beetle infestation became visible in 2008. Photo: Ulf Grandin, SLU

Stora Göljån

Mount Fulufjäll, national park since 2002, is located on the border to Norway in the southern part of the Swedish alpine region with a maximum altitude of 1042 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1c). At elevations above 900 m a.s.l., the mountain resembles a plateau covered by dry heaths with lichens and grass heaths. Fairly steep slopes descend to the surrounding land from about 400 to 500 m a.s.l. Mountain birch species (Betula pubescens ssp. czerepanovii (N. I. Orlova) Hämet-Ahti) reach from 800 to 925 m a.s.l., whereas Norway spruce dominates the lower parts of the slopes. The headwater stream Stora Göljån begins on a plateau at ≈1000 m a.s.l. and discharges on the eastern side of Mount Fulufjäll in River Fulan. The catchment area is 21.8 km2 with alpine heath as the dominant land cover (Table 1). An old (>160 years) nonmanaged Norway spruce forest covers the lower parts of the catchment (31 %, Fig. 2) (Snäll 1997).

During August 30–31, 1997, a rainstorm hit Mount Fulufjäll, and a new Swedish precipitation record of 276 mm within 24 h was measured at Lake Rösjön on the plateau. Further south on the eastern side of the mountain, an even higher precipitation of 300–400 mm 24 h−1 was estimated (Vedin et al. 1999). The resulting flashflood increased the total water discharge in Stora Göljån and the neighboring stream Lilla Göljån (total catchment area 35.9 km2) from an annual average discharge of 0.4 to about 300 m3 s−1 at the joint outlet in Fulan (Vedin et al. 1999). The amount is comparable with the annual average discharge of 353 m3 s−1 in the River Dalälven outlet at Bothnian Sea (catchment area 28 919 km2). The flashflood completely changed the streambed geomorphology downstream the plateau and created new flood channels in the coarse alluvium (Borgström et al. 1999). The erosive force was enormous, and the flood transported large boulders (>1 m3) over distances up to 100 m downstream and cleared the vegetation along broad riparian strips (often up to 50 m broad clearings). Damming caused by piles of uprooted trees and other vegetation trapped course and fine sediments, which at some occasions during the flood raised the water level up to 8.5 m from the present level and expanded the stream width in the order of 200–250 m (Borgström et al. 1999). For a detailed description of the meteorological, hydrologic, and geomorphologic effects of this event, see Vedin et al. (1999) and Borgström et al. (1999).

In the 3 years following this event, bark- and wood-boring beetles attacked the uprooted trees, while the mortality of standing trees along the riparian forest edge peaked in the second year after the rainstorm (Figs. 3, 5) (Schroeder and Lindelöw 2003). Compared with the flashflood effects on stream geomorphology and possible impacts on the benthic macroinvertebrate fauna in mind, the bark beetle outbreak was of minor importance.

Materials and methods

Aneboda IM

Tree layer surveys

The forest at Aneboda is monitored every fifth year in permanent circular plots of 314 m2 located in a regular grid (50 × 50 m) over the whole catchment. Recordings were scheduled to be performed in 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2011. However, due to the storm in January 2005, and the subsequent massive bark beetle attack observed in 2008, extra inventories were conducted during early spring and late autumn in 2009. The spring inventory gave information about bark beetle effects between 2006 and 2008. The autumn inventory showed bark beetle effects during the growing season in 2009. The inventories are based on individual trees, and five classes were used for classifying the degree of bark beetle infestation (no signs, to dead trees; see Electronic Supplementary Material for details).

Soil water, GW, and stream water

During spring, summer, and autumn, SW from Aneboda IM was collected in lysimeters (P80 ceramic cups, 0.3 bar underpressure) in the middle of the B-horizon and at 30–50 cm below the soil surface in organic soils. The lysimeters are located in recharge areas, intermediate zones, and discharge areas (described in Löfgren et al. 2011). Adjacent to the lysimeters, GW was collected in plastic tubes with a diameter of 32 mm, sealed at the bottom and with holes being drilled into the lower 0.5 m in the recharge area (4.2 m), intermediate zone (2.1 m), and discharge area (1.0 m) (Löfgren et al. 2011). Filtered GW samples (<0.45 µm) were collected in winter, spring, summer, and autumn. Stream water was sampled biweekly at the outlet, where daily water discharge was registered. The water was collected in rinsed polyethylene bottles and sent to the laboratory at the Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, SLU for chemical analyses, which were initiated within 1 day after sampling. For further details on methodology and locations of the sampling device, see Löfgren et al. (2011). Annual mass transport of physiochemical compounds was estimated from daily discharge at the stream outlet and linearly interpolated daily concentrations.

The analytic methods are accredited by the Swedish Board for Accreditation and Conformity Assessment (www.swedac.se) and follow Swedish standard methods (see Supplementary material).

Stora Göljån

Benthic macroinvertebrates

Macroinvertebrates were sampled in Stora Göljån in 1992, 1996, and each year between 1997 and 2012. In 1992, 1996, and 2006, only spring sampling occurred, and for 2009, only autumn samples are available. In the other years, macroinvertebrates were sampled both during spring and autumn. After the flashflood, Stora Göljån was plugged approximately 50 m upstream of the original sampling site, and a new stream channel was formed joining Lilla Göljån approximately 250 m downstream of the sampling site. From autumn 1997 and onwards, the benthic macroinvertebrate samples were taken in Stora Göljån approximately 100 m upstream from the original location with similar water discharge and mineral substratum (stones and boulders).

Macroinvertebrates were sampled using a Surber sampler with 0.04 m2 sampling surface according to Swedish standard (SS/EN 28 265). In the field, invertebrate samples were preserved in 70 % ethanol. In the laboratory, samples were sorted, and invertebrates identified and counted using dissecting and light microscopes. Organisms were identified to the lowest taxonomic unit possible, generally to species level.

The organic material, also obtained from the Surber sampling, was sorted and determined into different components (algae, detritus, other substrate) and then quantified as ash-free dry weight (AFDW). AFDW (= M 105 °C − M 500 °C) was quantified as the difference in sample weights after oven drying for 24 h at 105 °C (M 105 °C) and after combustion for 4 h at 500 °C (M 500 °C). Before weighing, the samples were allowed to be cooled in exciccator. Throughout the investigation, the same person (Per Mossberg, Grönbo konsult HB) conducted sampling, sample preparation, identification of taxa, and organic material analyses.

Stream water

At Stora Göljån, stream water was sampled on a monthly basis. Before the flashflood, the samples were collected from a bridge just downstream the benthic macroinvertebrate sampling site. After the flashflood, this stream channel was clogged, and the samples were taken from shore just downstream the new benthic fauna sampling site. The water was collected in rinsed polyethylene bottles and before 2009, sent for chemical analysis to the SWEDAC accredited MEANA laboratory in Uppsala. From January 2009 and onwards, the samples were sent to the laboratory at the Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, SLU for chemical analysis. Except for PO4 3− and TP, the two laboratories used the same analytic methods, and SO4 2− and Cl− were in fact analyzed at SLU (2014) throughout the monitoring period. At MEANA, PO4-P and TP were manually analyzed in a 5-cm quartz cuvette.

Statistical analyses

The Aneboda IM SW, GW, and stream water N concentration time series were separated into Reference (before January 8, 2005), Storm-felling (January 8, 2005–December 31, 2007) and Bark beetle periods (after January 1, 2008). Differences in N concentrations between periods were tested by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a post hoc comparison for each pair using Bonferroni-corrected Wilcoxon test (JMP version 10.0.2d1). Due to the restricted number of observations on TN during the storm-felling period for SW (n = 3–15 per season and soil stratum) and GW (n = 3 per season and sampling site for all N compounds), we have not tested for seasonality.

In total, eight metrics describing the macroinvertebrate assemblage structure for each sampling occasion (spring and autumn) and year were calculated, and due to statistical differences in macroinvertebrate metrics between seasons, further analysis was separated by season. However, due to the lack of autumn samples and the limited number of spring samples prior to the catastrophic event, we were not able to perform any statistical tests on differences between metrics before and after the storm.

The eight biological metrics were used to analyze possible changes in diversity and composition of macroinvertebrate assemblages. Taxon richness was selected as a qualitative measure of changes in assemblage diversity. In addition, assemblage diversity was calculated as Shannon (Shannon and Weaver 1949) and Simpson (Simpson 1949) diversity as well taxon distinctness. The latter is a diversity measure based on the relatedness of the species within a sample (Warwick and Clarke 2001). Further, a detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was performed to show temporal changes in taxonomic composition. DCA is an unconstrained ordination technique, which finds the main factors/gradients in large, species-rich, but usually sparse data matrices (ecological community data).

Simple linear regression analyses with metrics versus time were performed to display possible changes in metrics over time, especially focused on the time after the event.

To evaluate the relationships between macroinvertebrate assemblages and environmental factors and to assess which factors that can explain changes in the species assemblage of benthic macroinvertebrates over time, a canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was performed with physicochemical data, including organic substrate parameters expressed as AFDW (Table 2).

Metrics have been calculated using Asterics version 3.3.1 (http://www.fliessgewaesserbewertung.de); DCA and CCA have been performed using CANOCO 4.5 (ter Braak and Smilauer 1997–2002); and regressions have been made using JMP 10 (SAS 2013).

Results

Tree layer effects at Aneboda IM

Before the storm, the fraction of dead Norway spruce trees [standing and downed, >5-cm diameter at breast height (dbh)] in respect of the monitored plots was about 22 % (Fig. 5). The year after the storm, this fraction increased to 32 %. In the following years, the number of dead Norway spruce trees annually increased by ≈5 % mainly as an effect of bark beetles. During the scheduled inventory in 2011, several of the most affected plots were not monitored, as it was considered too dangerous to enter the maze of fallen logs.

The two extra inventories of bark beetle infestation in 2009 showed that bark beetles affected basically all spruces >5 cm dbh. Only 0.7–2 % of the trees were unaffected (total number of investigated trees, n = 1053). Half of the trees had minor damages (class 2). Most of these trees did not change class between the two surveys. Between 2006 and 2008, 17 % of the Norway spruce trees died. During the summer 2009, another 8 % of the trees died. In 2011, we recorded that yet another 11 % of the Norway spruce trees had died. However, this percentage should be actually higher as several plots with numerous dead and downed trees were excluded from the 2011 inventory due to safety reasons.

The highest impact by the bark beetles was on larger trees. For Norway spruce trees with diameters <20 cm, the fraction of dead trees per plot was about the same in all the four inventories. For larger trees, the fraction of dead trees increased drastically in the 2011 inventory (Fig. 6).

Nitrogen effects at Aneboda IM

There were no indications that the storm felling in January 2005 caused any increased N concentrations in SW in the peaty riparian soils (Fig. 7; Table 3). In the B-horizon, however, the NO3-N concentration was significantly higher after the bark beetle attack (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7; Table 3). This affected the TN concentrations as well with significantly higher TN concentrations in the order: Reference < Storm felling < Bark beetle period (Table 3). Except for at 3.2-m soil depth in the intermediate zone, showing significantly lower NH4-N concentrations during the storm-felling period, no differences between periods were found for N in GW in the recharge areas and intermediate zones. In the discharge area, however, significantly higher NH4-N and TN concentrations were found during the bark beetle period both at 1.0-m and 2.0-m soil depths, while excess NO3-N concentrations only were found at 1.0-m depth (Fig. 8; Table 3). The period after storm felling also showed significantly higher NH4-N, NO3-N, and TN concentrations in GW at 1-m soil depth (Table 3). Thus, the higher NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations in stream water after storm-felling and bark beetle outbreak (Fig. 9; Table 3) were in agreement with relationships between stream water and GW concentrations in the riparian soils as shown earlier (Löfgren et al. 2011). In stream water, the TN concentrations were in the order Storm-felling < Bark beetle < Reference period, implying higher Org-N concentrations before the storm event (Fig. 9).

Time series for the period 1996–2012 (Box-plots, quantiles) of soil water NO3-N, NH4-N, and TN concentrations in B-horizon in recharge and intermediate zones (data from eight lysimeters), and in peat in discharge areas (data from four lysimeters) at Aneboda IM. Horizontal lines at 1000 µg L−1, vertical dotted line in January 2005 (storm felling), and vertical line in January 2008 (bark beetle attack)

Time series for the period 1996–2012 on GW NO3-N, NH4-N, and TN concentrations in recharge areas (red large dots = 4.2-m soil depth), intermediate zones (blue large dots = 2.1-m soil depth, small dots = 3.2-m soil depth), and discharge areas (orange large dots = 1.0-m soil depth, small dots = 2.0-m soil depth) at Aneboda IM: horizontal lines at 1000 µg L−1, vertical dotted line in January 2005 (storm felling), and vertical line in January 2008 (bark beetle attack)

Except for a few lysimeters in the B-horizon after the bark beetle attack and some GW piezometers throughout the period, the NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations rarely exceeded 1 mg L−1 (Figs. 7, 8). However, after 2010, there were three lysimeters in the B-horizon and one piezometer at 3.2-m soil depth in the intermediate zone showing >5 mg NO3-N L−1. In the latter, NO3-N concentrations up to 9 mg L−1 were registered after the bark beetle outbreak. In stream water, the NO3-N concentrations rarely exceeded 500 µg L−1 and the NH4-N concentrations were generally below 100 µg L−1 during this period (Fig. 9). The TN concentrations varied between 500 and 1500 µg L−1 (Fig. 9). There were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test) between the periods in annual stream export of NH4-N, NO3-N, and TN at Aneboda IM. The average annual exports were 0.23, 0.06, and 1.93 kg N ha−1 year−1, respectively (Table 5).

Macroinvertebrate effects at Stora Göljån

The structure and the diversity of the macroinvertebrate assemblage of Stora Göljån were relatively stable and did not vary much through time or between seasons except for the first year after the flashflood (Table 4; Figs. 10a, 11). The number of taxa in autumn ranged from 7 in 1997 (immediately after the flooding) to 35 taxa found in 2008. Number of taxa in spring ranged from 4 taxa found in 1998 (first spring after the event) to 34 taxa recorded in spring 1996. The event in August 1997 clearly caused a severe decrease in species richness in autumn 1997 and spring 1998, but thereafter, species richness increased steadily to pre-event conditions (Fig. 10a).

After the event, the abundance of macroinvertebrates showed high interannual variability, with some peaks like in autumn 2002, when the highest abundance (9000 individuals m−2) was found (Fig. 10b). In contrast to the number of taxa, grand mean abundances were different between seasons (4484 in autumn vs. 2639 individuals m−2 in spring, p = 0.02) (Table 4). In autumn 1997, directly after the flooding, the lowest abundance (62.5 individuals m−2) was recorded. Spring abundance was generally lower, and records ranged from 565 individuals m−2 in 1999 (i.e., 1.5 years after the event) to over 5700 individuals m−2 found in 2004. However, after 2004, both spring and autumn abundances showed a slight decreasing trend reaching somewhat lower numbers at the beginning of the actual decade.

Both Simpson and Shannon diversities also showed great interannual variability with the spring diversity being somewhat, but not significantly, higher than the diversity at autumn (Fig. 10c, d). The grand mean diversity values were different between seasons for both Simpson (0.46 vs. 0.65; p = 0.006) and Shannon diversities (1.19 vs. 1.55, p = 0.03), but not for taxonomic distinctness (4.14 vs. 3.58) (Table 4). In autumn, minimum Simpson and Shannon diversities (0.16 and 0.48, respectively) were recorded in 2001, while maximum Simpson and Shannon diversities (0.83 and 2.29, respectively) were recorded in 2004. In spring 1998, a few months after the event, the lowest Simpson (0.06) and Shannon (0.16) diversities were recorded. Both indices peaked many years later (2005 and 2010, respectively). Maximum Simpson diversity coincided with the highest taxonomic distinctness obtained in spring 2005, i.e., 4.19 (Fig. 10e). Taxonomic distinctness was slightly higher in autumn, but not significantly different from the spring. Autumn taxonomic distinctness values ranged from 3.46 (2008) to 4.93 (2000) and from 2.94 (2011) to 4.19 (2005) in spring, but the slightly higher distinctness in autumn was not significantly different from that in spring. DCA of individual years and seasons showed distinct grouping in macroinvertebrate assemblage’s composition in Stora Göljån (Fig. 11).

The first DCA axis explained 28 % (eigenvalue = 0.72) of the total inertia, i.e., the total variance explained (eigenvalue = 2.56) in assemblage’s composition and clearly separating seasons (t test of axis 1 DCA scores, p < 0.001). The second axis accounted for another 9.7 % of the variability, and was more related to within-season interannual variability. Basically, there are two groups showing distinct assemblage’s compositions for autumn and spring, respectively and some samples separated from these groups having deviating macroinvertebrate assemblage’s structures (G99S, G02S, G03S, G11S, G98A, and G98S, Fig. 11). However, there was also an overlap, where the invertebrate composition in autumn (G97A and G08A) was more similar to the spring macroinvertebrate composition and vice versa, while the composition in spring 2012 (G12S) was more similar to that of the samples obtained in autumn.

CCA with water chemistry and organic substrate as explanatory variables and macroinvertebrate assemblages (species compositions) of spring and autumn samples as independent variables showed that mosses, water color (absorbance at 420 nm), and pH were the most important determinants of assemblage structure (Fig. 12). The first two CCA axes explained 55.8 % of the variation in invertebrate composition (axis 1 explained 28.8 %, and the second axis accounted for another 27 % of the variability). As already shown in the DCA of Fig. 11, spring and autumn samples were clearly separated, where pH was associated with autumn samples, and water color was associated with spring samples. The absence of Fontinalis sp. and Sphagnum sp. in spring, especially in the years 1997, 2000, 2003, 2005, and 2006, was positively correlated to spring assemblage structure.

CCA triplot showing samples and species assemblage’s compositions for different years and seasons in the stream of Stora Göljån as well as the four explanatory factors significantly explaining assemblage structure variability. Samples are indicated as G Göljån; sampling year, and season as A autumn, S spring. Species are represented as numbers, see taxa list

Discussion

Evaluating stochastic climatic events: A methodological challenge

Evaluating the effects of stochastic weather events is a challenge. Before an event, you do not know where or when it occurs. Hence, it is impossible to use scientific methods based on reference periods and “control” and “treatment” sites for such studies. By chance, two Swedish monitoring sites were hit by extreme weather events, contributing with pre- and post-event data. The assessments are restricted to the types of data collected, and the Stora Göljån macroinvertebrate study suffers from poor descriptions of streambed characteristics at the two sampling sites. However, an earlier study on geomorphologic effects in Stora Göljån (Borgström et al. 1999) showed that similar weather events have occurred historically and that the sediments in the lower parts consist of the locally produced and the recently deposited stones and boulders of varying but similar sizes (Figs. 2, 3). Hence, from a minerogenic and texture point of view, the pre- and post-event sampling sites are rather similar. Besides the enormous translocation of minerogenic matter, the largest difference in Stora Göljån was the vegetation cover (cf. Fig. 5), which was completely removed by the intense erosion during the flashflood. Accumulation of the newly formed large woody debris (LWD) along the shores (Fig. 3) was another difference. LWD was also present before the event, but in much lower quantities and probably of another substrate quality compared with the post-event conditions (cf. Fig. 5). Hence, the shift in macroinvertebrate sampling site between pre- and post-event periods must have had marginal impact on the results compared with the flashflood-created substrate changes.

Nitrogen effects at Aneboda IM

The storm Gudrun had a relatively low impact on the tree layer at Aneboda IM. The storm-felling event increased the fraction of standing and downed (>5 cm dbh) Norway spruce trees from 22 to 32 %, while the following bark beetle infestation had a much larger effect with an annual 5 % increase of dead trees. Especially larger Norway spruce trees (>30 cm dbh) were killed, and 65–100 % of them were dead in 2011 (Fig. 6). The destruction of the mature spruce canopy together with the large disturbances of the soil by uprooted trees theoretically favors reduced evapotranspiration, increased mineralization of organic matter, and thereby increased losses of N to surface waters. However, these changes in combination with changes in light regime will most likely have stimulating effects on the ground- and field-layer vegetations having the potential to compensate for the excess N availability in the soil system (Mikkelson et al. 2013). Unpublished results from the inventories in summer 2013 confirm that the drastic perturbation of the abiotic environment have resulted in abrupt changes in the field layer. For example, the wavy hair-grass (Deschampsia flexuosa L.) has changed from a mean cover of about 1 % before 2010 to >50 % in several monitoring plots. Another major change is the appearance of raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) in high densities. Both these species are nitrophilic and commonly associated with clear-cuts. At Aneboda IM, the large increase in density of these species is probably an effect of the change in the light regime from a relatively dark understory to fully exposed ground (Fig. 4) and good availability of inorganic N in the soils.

In this study, increased concentrations of NO3-N were only found in SW in the B-horizon and in shallow GW (1 m) in the discharge areas. The riparian soils also exhibited excess NH4-N concentrations related to the death of Norway spruce trees (Table 3). The leakage of inorganic nitrogen to the stream, however, was relatively moderate, and the NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations rarely exceeded 100 and 1000 µg N L−1, respectively. This increase was to a large extent balanced by lower Org-N concentrations (Fig. 9). In fact, it was not possible to observe any statistically significant effects on the stream N export coupled to the storm-felling or bark beetle outbreak periods (Table 5). These relatively few and modest effects on the N dynamics are in agreement with other studies performed in less N-enriched environments in North America, but clearly deviate from the results found in “N-saturated” systems in Central Europe (see Mikkelson et al. 2013 and references therein).

However, some of our 5-year long time series from SW and GW after the bark beetle infestation indicate that the net-loss of NH4-N and NO3-N may not have reached a maximum in certain areas of the catchment (Figs. 7, 8) and that the prolonged leakage may be expected to the stream showing the highest NO3-N concentrations in the autumn of 2011 (Fig. 9). Clow et al. (2011) did not find increased NO3-N concentrations in Colorado streams within 9 years from mountain pine beetle-induced tree mortality, but the TN concentrations increased. Vrba et al. (2014) documented excess NO3-N concentrations during the 6 years in lakes in the German part of Bohemia, and Oulehle et al. (2013) found similar results in lakes on the Czech side. Both the latter studies represent N enriched environments. While the N deposition in throughfall in Bohemia (14 kg N ha−1 year−1) exceeded N in bulk deposition by 30–40 % (Oulehle et al. 2013), the N in throughfall (2.4 kg N ha−1 year−1) was significantly lower compared with bulk deposition (7.5 kg N ha−1 year−1) at Aneboda IM (Table 1). This strongly indicates N-limited forest ecosystems at Aneboda IM.

Besides a major change in the field vegetation (unpublished data) and modest atmospheric N deposition, the remaining living trees (cf. Fig. 4) may have a profound impact on the N dynamics, explaining the N-concentration heterogeneity in SW and GW. Another factor not to overlook is the tremendous amount of LWD that has been accumulated within the catchment. It is well known that LWD with high C/N ratios may act as N sinks during decomposition (Hyvönen et al. 2000; Brais et al. 2006; Palviainen et al. 2010). Especially the stumps seem to accumulate N, and during the first 5 years after harvesting, a study from southern Finland showed about twofold increases in stump N content, corresponding to 2.2–2.8 and 1.4–1.8 kg N ha−1 year−1 in Scots pine and Norway spruce stands, respectively (Palviainen et al. 2010). Adding boles and large branches, the N uptake by LWD may constitute a significant factor for explaining why Aneboda IM still exhibits a fairly closed N budget with limited excess leakage of N to the stream.

We have to reject our first prediction of no impact by storm felling and bark beetle outbreak on the N concentrations in the Aneboda IM stream. The SW and GW data indicate that excess NO3-N leakage to the stream may continue for still some more years to come. However, the NO3-N concentrations will probably maintain at relatively low levels not tangibly increasing the export of N from the catchment compared to those levels expected to find if it was covered with a vital Norway spruce forest (Table 5).

Macroinvertebrate effects at Stora Göljån

The extreme rain event at Mount Fulufjäll in 1997 generated a tremendous flashflood in Stora Göljån, which severely altered the streambed geomorphology, uprooted trees, and other vegetation along broad riparian strips. Total macroinvertebrate density and taxa richness decreased dramatically shortly after the event in autumn 1997 and remained low also at the first post-event investigation in spring 1998 (Table 4). However, benthic fauna recovered quite rapidly reaching almost pre-event densities, richness, and diversity within the first post-event year (Table 4). This quick recovery to pre-event numbers of taxa and also diversity was somewhat unexpected at a first glance. However, flow peaks annually affect the Stora Göljån stream during snowmelt, although their intensities are not at all comparable with the enormous forces created by the 1997 flashflood. This annually recurring disturbance pattern may have contributed to the adaptations that the macroinvertebrate assemblage has evolved to show resilience to discharge events (e.g., Lytle and Poff 2004).

Further, the assemblage structure did not change after the flashflood. This is also unexpected because of the severe damage to the riparian zone vegetation and the substrate. One would expect a change of the proportion of certain functional feeding groups within the assemblage. For instance, due to the reduced or loss of shading caused by the damage to the riparian forest, the proportion of grazers is expected to increase due to the expected increase of periphytic biomass, whereas shredders should decrease due to the reduced input of allochthonous organic material. However, in our study, neither the algal biomass increased nor the proportion of either grazers or shredders changed significantly after the flashflood. This finding is in contrast to other studies, where flashfloods altered the streambed and also the riparian zone in similar ways as at Stora Göljån, but where stream macroinvertebrate community composition changed tremendously, and the recovery of taxon richness and density was highly delayed (e.g., Minshall et al. 1997; Vieira et al. 2004). However, the recovery might be rapid even after large, single floods due to traits allowing for fast recolonization. For instance, no significant difference has been found between pre- and post-flood benthic assemblages within a 2-month-period of a single flood within a 100-year period in River Isar, Germany (Hering et al. 2004).

In our study, the recovery occurred within the first post-event year. The quick recovery might be explained not just by a high resilience of the assemblage, but more because a new stream channel was formed by the flashflood offering new habitats with resources relatively quickly available and thus facilitating recolonization from water sources nearby. Indeed, sampling post-flood was performed in this new stream channel, not far away from the confluence of the Stora Göljån stream with river Fulan, from which colonists, especially insects, may disperse. The river may act as an excellent source, and the more or less open land due to the cutting of a large amount of forest within the Fulan catchment may have contributed to easier and quicker dispersal of flying insect species to the new habitats. Drifting from upstream not so seriously damaged tributaries on the plateau may also have acted as refuges, facilitating the recolonization.

Hence, we have to reject also our second prediction of strong and long-term impact on benthic macroinvertebrates in Stora Göljån due to the geophysical disturbances by the flashflood. However, more subtle impacts may have had longer duration, but this cannot be evaluated due to pre-event data constraints.

Conclusions

Long-term monitoring data from Aneboda IM and Stora Göljån make it possible to assess the effects of two extreme weather events. The results indicate long-term (>5 years) increased NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations in aqueous media at Aneboda IM primarily induced by the bark beetle infestation following the storm. The enhanced N concentrations were, however, relatively modest (generally <1 mg L−1) probably as a result of low N deposition, a remaining cover of N-limited young trees, and compensatory factors such as rapidly evolving field vegetation and N retention by LWD with a high C/N ratio. The extreme flashflood at Stora Göljån, completely changing the morphology of the stream channel, induced only short-term (1 year) effects on the benthic fauna diversity and composition. The quick biological recovery may be explained by the creation of new habitats with resources relatively quickly available and recolonization from water sources nearby.

Both these case studies illustrate that Swedish freshwater systems can have a remarkable resilience and fast recovery, even after massive disturbances. The results are partly in contrast to extreme weather event studies elsewhere showing much more dramatic effects on water chemistry and benthic invertebrates.

References

Anonymous. 2006. Stormen 2005 – en skoglig analys. Report 1:2006. Jönköping: Skogsstyrelsen. 199 pp. (in Swedish, English summary).

BACC. 2008. Assessment of climate change for the Baltic Sea basin. In Regional climate studies, vol XII, 474 pp. Berlin: Springer.

Boix, D., E. García-Berthou, S. Gascón, L. Benejam, E. Tornés, J. Sala, J. Benito, C. Munné, et al. 2010. Response of community structure to sustained drought in Mediterranean rivers. Journal of Hydrology 383: 135–146.

Borgström, I., S.A.O. Cousins, A.C. Dahlberg, and L.O. Westerberg. 1999. The 1997 Flashflood at Mount Fulufjället, West Central Sweden: Geomorphic and vegetational investigations of Stora Göljån Valley. Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography 81: 369–382. doi:10.1111/1468-0459.00066.

Brais, S., D. Paré, and C. Lierman. 2006. Tree bole mineralization rates of four species of the Canadian eastern boreal forest: Implications for nutrient dynamics following stand-replacing disturbances. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 2331–2340. doi:10.1139/x06-136.

Clow, D.W., C. Rhoades, J. Briggs, M. Caldwell, and W.M. Lewis. 2011. Responses of soil and water chemistry to mountain pine beetle induced tree mortality in Grand County, Colorado, USA. Applied Geochemistry 26: 174–178. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2011.03.096.

Death, R.G., and M.J. Winterbourn. 1994. Environmental stability and community persistence: A multivariate perspective. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 13: 125–139.

Edburg, S.L., J.A. Hicke, P.D. Brooks, E.G. Pendall, B.E. Ewers, U. Norton, D. Gochis, E.D. Gutmann, et al. 2012. Cascading impacts of bark beetle-caused tree mortality on coupled biogeophysical and biogeochemical processes. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10: 416–424. doi:10.1890/110173.

Fritz, K.M., and W.K. Dodds. 2004. Resistance and resilience of macroinvertebrate assemblages to drying and flood in a tallgrass prairie stream system. Hydrobiologia 527: 99–112.

Griffin, J.M., M. Simard, and M.G. Turner. 2013. Salvage harvest effects on advance tree regeneration, soil nitrogen, and fuels following mountain pine beetle outbreak in lodgepole pine. Forest Ecology and Management 291: 228–239. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.11.029.

Grodzki, W., R. Jakuš, E. Lajzová, Z. Sitková, T. Maczka, and J. Škvarenina. 2006. Effects of intensive versus no management strategies during an outbreak of the bark beetle Ips typographus (L.) (Col.: Curculionidae, Scolytinae) in the Tatra Mts. in Poland and Slovakia. Annals of Forest Science 63: 55–61. doi:10.1051/forest:2005097.

Haanpää, S., S. Lehtonen, L. Peltonen, and E. Talockaite. 2006. Impacts of winter storm Gudrun of 7th–9th January 2005 and measures taken in Baltic Sea Region. Report. The Astra Project. Assessed October 2013, from http://www.astra-project.org/sites/download/ASTRA_WSS_report_final.pdf.

Hart, D.D., and C.M. Finelli. 1999. Physical–biological coupling in streams: The pervasive effects of flow on benthic organisms. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30: 363–395.

Hering, D., M. Gerhard, R. Manderbach, and M. Reich. 2004. Impact of a 100-year flood on vegetation, benthic invertebrates, riparian fauna and large woody debris standing stock in an alpine floodplain. River Research and Applications 20: 445–457.

Huber, C. 2005. Long lasting nitrate leaching after bark beetle attack in the highlands of the Bavarian Forest National Park Bayerisches Staatsministerium ELF with the projects V50B and V58. Journal of Environmental Quality 34: 1772–1779. doi:10.2134/jeq2004.0210.

Hyvönen, R., B.A. Olsson, H. Lundkvist, and H. Staaf. 2000. Decomposition and nutrient release from Picea abies (L.) Karst. and Pinus sylvestris L. logging residues. Forest Ecology and Management 126(2): 97–112. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00092-4.

IPCC. 2012. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. In A special report of working groups I and II of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, ed. C.B. Field, V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, et al., 582 pp. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaňa, J., K. Tahovská, and J. Kopáček. 2013. Response of soil chemistry to forest dieback after bark beetle infestation. Biogeochemistry 113: 369–383. doi:10.1007/s10533-012-9765-5.

Lake, P.S. 2000. Disturbance, patchiness, and diversity in streams. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 19: 573–592.

Lake, P.S. 2003. Ecological effects of perturbation by drought in flowing waters. Freshwater Biology 48: 1161–1172.

Lake, P.S. 2007. Flow-generated disturbances and ecological responses: Floods and droughts. In Hydroecology and ecohydrology: Past, present, and future, ed. P.J. Wood, D.M. Hannah, and J.P. Sadler, 75–88. Chichester: Wiley.

Lytle, D.A., and N.L. Poff. 2004. Adaptation to natural flow regimes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19: 94–100.

Långström, B., Å. Lindelöw, M. Schroeder, N. Björklund, and P. Öhrn. 2009. The spruce bark beetle outbreak in Sweden following the January-storms in 2005 and 2007. IUFRO Forest Insect and Disease Survey in Central Europe, Conference Paper, 15–19 September 2008, Štrbské Pleso, Slovakia, 8 pp.

Löfgren, S., M. Aastrup, L. Bringmark, H. Hultberg, L. Lewin-Pihlblad, L. Lundin, G. Karlsson, and B. Thunholm. 2011. Recovery of soil water, groundwater, and streamwater from acidification at the Swedish Integrated Monitoring Catchments. AMBIO 40: 836–856. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0207-8.

Mikkelson, K., L. Bearup, R. Maxwell, J. Stednick, J. McCray, and J. Sharp. 2013. Bark beetle infestation impacts on nutrient cycling, water quality and interdependent hydrological effects. Biogeochemistry 115: 1–21. doi:10.1007/s10533-013-9875-8.

Minshall, G.W., C.T. Robinson, and D.E. Lawrence. 1997. Postfire responses of lotic ecosystems in Yellowstone National Park, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 54: 2509–2525.

Oulehle, F., T. Chuman, V. Majer, and J. Hruška. 2013. Chemical recovery of acidified Bohemian lakes between 1984 and 2012: The role of acid deposition and bark beetle induced forest disturbance. Biogeochemistry 116: 83–101. doi:10.1007/s10533-013-9865-x.

Palviainen, M., L. Finér, R. Laiho, E. Shorohova, E. Kapitsa, and I. Vanha-Majamaa. 2010. Carbon and nitrogen release from decomposing Scots pine, Norway spruce and silver birch stumps. Forest Ecology and Management 259(3): 390–398. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.10.034.

Peterson, C.G., and R.J. Stevenson. 1992. Resistance and resilience of lotic algal communities: Importance of disturbance timing and current. Ecology 73: 1445–1461.

Poff, N.L. 1992. Why disturbances can be predictable: A perspective on the definition of disturbance in streams. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 11: 86–92.

Poff, N.L. 1997. Landscape filters and species traits: Towards mechanistic understanding and prediction in stream ecology. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 16: 391–409.

Resh, V.H., A.V. Brown, A.P. Covich, M.E. Gurtz, H.W. Li, G.W. Minshall, S.R. Reice, A.L. Sheldon, et al. 1988. The role of disturbance in stream ecology. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 7: 433–455.

Rhoades, C.C., J.H. McCutchan, L.A. Cooper, D. Clow, T.M. Detmer, J.S. Briggs, J. D. Stednick, T.T. Veblen, et al. 2013. Biogeochemistry of beetle-killed forests: Explaining a weak nitrate response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221029110.

SAS. 2013. JMP—Statistics Made visual. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Schroeder, L.M., and Å. Lindelöw. 2002. Attacks on living spruce trees by the bark beetle Ips typographus (Col. Scolytidae) following a storm-felling: A comparison between stands with and without removal of wind-felled trees. Agricultural and Forest Entomology 4: 47–56.

Schroeder, L.M., and Å. Lindelöw. 2003. Response of Ips typographus (Scolytidae: Coleoptera) and other bark- and wood-boring beetles to a flash-flood event. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 18: 218–224. doi:10.1080/02827581.2003.9728292.

Shannon, C.E., and W. Weaver. 1949. The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Simpson, E.H. 1949. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163: 688.

SLU, 2014. Water chemical and physical analyses. Accessed September 9, 2014, from http://www.slu.se/en/departments/aquatic-sciences-assessment/laboratories/geochemical-laboratory/water-chemical-analyses.

Snäll, T. 1997. Regional monitoring of forested areas in Dalarna Länsstyrelsen Dalarna Miljövårdsenheten, vol. SDTY/W/MVE-97/0002, Falun, 37 pp (in Swedish).

Starr, M. 2011. Integrated monitoring in Sweden: Editorial. AMBIO 40: 833. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0198-5.

Tahovská, K., J. Kopáče, and H. Šantrůčková, 2010. Nitrogen availability in Norway spruce forest floor—the effect of forest defoliation induced by bark beetle infestation. Boreal Environmental Reasearch 15(6): 553–564.

ter Braak, C.J.F., and P. Smilauer. 1997–2002. Canoco for Windows. Wageningen: Plant Research International.

Townsend, C.R., S. Dolédec, and M.R. Scarsbrook. 1997. Species traits in relation to temporal and spatial heterogeneity in streams: A test of habitat templet theory. Freshwater Biology 37: 367–387.

Valinger, E., and J. Fridman. 2011. Factors affecting the probability of windthrow at stand level as a result of Gudrun winter storm in southern Sweden. Forest Ecology and Management 262(3): 398–403. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2011.04.004.

Vedin, H., A. Eklund, and H. Alexandersson. 1999. The rainstorm and flashflood at Mount Fulufjallet in August 1997: The meteorological and hydrological situation. Geografiska Annaler, Series A: Physical Geography 81: 361–368. doi:10.1111/1468-0459.00065.

Vieira, N.K.M., W.H. Clements, L.S. Guevara, and B.F. Jacobs. 2004. Resistance and resilience of stream insect communities to repeated hydrologic disturbances after a wildfire. Freshwater Biology 49: 1243–1259.

Vrba, J., J. Kopáček, J. Fott, and L. Nedbalová. 2014. Forest die-back modified plankton recovery from acidic stress. AMBIO 43: 207–217. doi:10.1007/s13280-013-0415-5.

Warwick, R.M., and K.R. Clarke. 2001. Practical measures of marine biodiversity based on relatedness of species. Oceanography and Marine Biology – An Annual Review 39: 207–231.

Acknowledgments

The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency financed the national monitoring at Aneboda IM and the regional monitoring at Stora Göljån, performed by the Department of Water Sciences and Assessment, SLU and the County Administration Board of Dalarna, respectively. The authors would like to thank the field and laboratory staff for their excellent work with sampling and chemical analyses. Special thanks are offered to Hans Olofsson, setting up the Stora Göljån monitoring program; Gunder Eriksson, Mörkret and Per Mossberg, Grönbo vattenkonsult, HB—both working at Stora Göljån; and Kjell Rosén, Asa field station and Tommy Pettersson, Vingåker both working at Aneboda IM, for their fearless but responsible work in the damaged forests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Löfgren, S., Grandin, U. & Stendera, S. Long-term effects on nitrogen and benthic fauna of extreme weather events: Examples from two Swedish headwater streams. AMBIO 43 (Suppl 1), 58–76 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0562-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0562-3