Abstract

We relax the common assumption of homogeneous beliefs in principal-agent relationships with adverse selection. Principals are competitors in the product market and write contracts also on the base of an expected aggregate. The model is a version of a cobweb model. In an evolutionary learning set-up, which is imitative, principals can have different beliefs about the distribution of agents’ types in the population. The resulting nonlinear dynamic system is studied. Convergence to a uniform belief depends on the relative size of the bias in beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Usually in mechanism design it is assumed that players have a subjective probability distribution over a set of possible elements or outcomes, which represents information privately known to other players. More specifically, in a principal–agent relationship with adverse selection the principal does not know the type of agent that she is matched with, but the distribution of types is common knowledge. Given a belief about this distribution, principals write court-enforceable contracts and agents self-select. Against this backdrop of the standard model, we introduce a bias on the part of the principals concerning their beliefs.

We model an aggregative game where principals are firms in an competitive market. Each principal is randomly matched with an agent who, in exerting effort, generates an output. Principals offer contracts based on the expected aggregate quantity and their belief over the distribution of types in the economy. Whereas the payoff of the agent depends on his (privately known) cost, the principals’ payoff is affected by the realized aggregate output and their beliefs.

We then study imitation equilibria in this market characterized by adverse selection and heterogeneous beliefs. The overarching question in the set-up then becomes: What are possible long-run equilibria of the beliefs principals hold? To this end, we formulate conditions under which biased beliefs can persist.

The aggregate of all individual firm decisions has an externality effect on all market participants. Building on that notion, we are interested in the way that a bias can affect that externality and, in a feedback effect, how the externality affects the bias. This means that, on the one hand, and this is to be expected, firms acting on biased beliefs influence the aggregate quantity in the market, because their individual output decisions are changed by the bias. On the other hand, however, convergence toward a beliefs equilibrium depends on the market quantity and the realized profits.

There is a long-term effect on market fundamentals, i.e., price, quantity, utilities and labor contracts. We show that the magnitude of the bias is decisive for the long-run outcomes. As intuition suggests, a large bias would be eradicated by market forces, whereas a modest degree of bias can persist. The reason is that for a range of biases the net of all externalities affecting an individual firm is positive.

Imitation in a game-theoretic setting is developed by Björnerstedt and Weibull [5], Vega-Redondo [22] and Schlag [18], where individuals imitate those strategies that offer higher profits. Apesteguia et al. [2] synthesize these approaches and test the theory with an experiment. Selten and Ostmann [20] study an imitation equilibrium in which higher profits also determine who will be imitated. In addition they introduce the notion of the reference group, which comprises all other players any individual would at all consider imitating. The precise definition of reference group is made in each case on the basis of the problem at hand. For example in a spatial sense as in Selten and Apesteguia [19], where firms imitate only neighboring firms. Or, as in Rothschild and Stiglitz [15] and Ania et al. [1], the reference group for principals—while not so named—includes contracts that are similar enough to one’s own contract.

We contribute to this literature on imitation. We assume (and w.l.o.g.) that some of the principals are optimistic about the distribution.Footnote 1 This means that they believe that the distribution of types is more favorable than it actually is.Footnote 2 As a result, the profits are different depending on the belief a principal holds. Hence, we study a polymorphic population characterized by unbiased and optimistic principals. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to introduce a bias for the uninformed market side in an evolutionary set-up.Footnote 3 In our model, learning takes place by imitation of other principals’ beliefs. That is, information about the beliefs is shared by word-of-mouth communication as in Banerjee and Fudenberg [4]. Alternatively, beliefs can be inferred if the menus of contracts are observable as in Ania et al. [1].

In putting the model squarely in the tradition of imitation, we effectively assume that principals are memoryless about past matches. Instead, we could assume that the lifespan is short. Alternatively, if we assumed principals able to revise beliefs as Bayesian updaters, then, with an appeal to the law of large numbers, the answer would be straightforward. As more information accumulates over time, Bayesian updating with perfect memory would ultimately lead to all principals having the same unbiased belief. However, in this scenario, the information requirements are strong, because principals have to live a sufficiently long time to collect enough data points. We imagine a continuum between a perfect Bayesian updater at the one end and imitation only at the other. A Bayesian approach requires that firms potentially live forever and that (in the long run) perfectly recover the underlying distribution of types. In assuming memorylessness, we are at the one end of the spectrum where the evolution of beliefs is not straightforward. Fundamentally, we are interested in studying potential outcomes if economic actors do not or are unable to accumulate enough observations to recover the true distribution. In this context, the assumption of memorylessness is a mathematical convenience.

In our set-up, the probability to change beliefs depends on the matching, the propensity to switch, and the payoff difference between principals. We partially follow Selten and Ostmann’s [20] notion of reference groups. There it is stated that individuals tend to compare with similar others (i.e., membership of the same reference group). In this sense, we introduce a mechanism that describes the willingness of individuals to compare themselves with others. To be concrete, consider a model with two types of agents. There is one group including the principals matched with a high-cost agent and the second with those matched with a low-cost agent. This lets us define a propensity to compare for each principal, which expresses the willingness to compare with a randomly chosen different principal. Hence, we do not restrict the comparison to a given member of a reference group, but rather we conceive of a probability representing the willingness of a given principal to compare herself with others. Whereas this assumption represents an extension of the notion of reference groups in economics, it is a common view in the social comparison theory, which is commonplace in other disciplines. Starting with Festinger [9], psychologists point out that individuals tend to carry out “social comparisons” preferably (but not exclusively) with similar others. The latter point suggests that our principals treat information gained from different reference groups differently. A precursor to our approach in experimental economics is the work by Todt [21]. The subjects in these early experiments tended to be more open to imitation if the situation of the other party was perceived to be more similar to their own.

Principals offer contracts that stipulate the production of a given quantity of a homogeneous good. Aside from a belief about the distribution of types, each principal also forms an expectation about the aggregate quantity produced in the market. We focus our attention on naive adaptive expectations, which implies that each principal writes a contract assuming that the aggregate quantity in a given period is the same as in the period before. The rationale is the following. Principals in our model do not know the salient characteristics of the market, simply because they are not aware that there are different beliefs. Rational expectations about the quantity would run contrary to this view of the role of principals and therefore are not useful in this respect.Footnote 4 Given the assumption about naive expectations, our model is then a version of a cobweb model where, traditionally, fluctuations arise due to a disconnect between the time quantities are chosen and prices are realized.

We focus on just two possible beliefs, but obviously one could imagine a population in which each principal holds her own prior belief about the distribution. Then, the switching process described above should sooner or later lead to a situation in which the polymorphism of the population consists of either two remaining strategies or a stable configuration with more than two beliefs present. Whereas the latter case would require an analysis of the conditions under which a configuration of multiple beliefs can coexist, the former is a study of convergence toward a unique belief. We focus on this case keeping in mind that this is a “reduced” problem, because we start the analysis at a moment in time in which a potentially large number of beliefs has already been eliminated from the population and where the only polymorphism consists of two beliefs.Footnote 5

The paper proceeds as follows: the next section introduces the interaction of the different groups in the model. The resulting dynamic system is studied in Sect. 3. Finally, we offer some concluding remarks in Sect. 4. All proofs are relegated to Appendix.

2 Population Interactions

In Sect. 2.1, we describe the interaction between principals and agents in the stage game of the model. Then, in Sect. 2.2, we set up and describe the interaction among principals with different beliefs. This entails defining a mechanism that allows principals to modify their beliefs and therefore change their contract offers in the stage game. Hence, in the next two subsections we derive the nonlinear map which governs the evolution of the population composition and of the quantity.

2.1 Stage Game

There are two large populations of principals and agents of equal size. Each principal wants to delegate a task to an agent in order to produce a quantity q. Agents are heterogeneous with regard to their ability to produce the quantity. They have a linear cost function defined as \(C\left( q,\theta \right) =\theta q\). As is standard, we assume that \(\theta \in \left\{ \underline{\theta },\overline{\theta }\right\} \), where \(\overline{\theta }>\underline{\theta }\) and we denote \(\Delta \theta =\overline{\theta }-\underline{\theta }\). The proportion of agents with marginal cost \(\underline{\theta }\) is \(v\in \left( 0,1\right) \). In the next step, the stage game will be defined.

Principals are heterogeneous in that they hold different beliefs about the distribution of agents’ abilities. In particular, we assume that some principals believe that the proportion of low-cost agents in the population is larger than it really is:

Assumption 1

Each principal has a belief \(\phi \) about the prevalence of low-cost agents, with \(\phi \in \{\rho ,v\}\) where \(\rho >v\). We will sometimes refer to those biased principals as optimistic.

The agent’s production provides a benefit to a principal i, which is measured by a function \(S(q_t^i,\tilde{q}_t)\), where \(q_t^i\) is the quantity produced by the agent working for principal i in period t and \(\tilde{q}_{t}\) is a sufficient statistic of the aggregate quantity in the market. The precise definition of \(\tilde{q}_{t}\) will be given below.

Timing Time is discrete. In a generic period t, the fraction of principals who write contracts on the basis of belief v is denoted by \(\alpha _{t}\).

The timing of the game follows the timing of the cobweb model where there is a lag between output decisions and realizations. In our model, this disconnect is between the contracting stage and the observability of outcomes. This means that the principal designs a contract in t for a quantity that is only observed in \(t+1\). The payment is conditioned on the observed quantity as well, contracted in t, but paid only when the quantity is observed. Technically speaking, the contracting stage takes place in a period t, when principals offer menus of contracts for the next period based on the beliefs as in Assumption 1.

The functional form ([23, 231]) of the benefit that the principal expects to gain in \(t+1\) is:

In t, each principal defines a mechanism \(\left\langle q_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) ,w_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) \right\rangle \) which entails a transfer \(w_{t+1}\) for each observed quantity in \(t+1\). We assume \(\beta \) to be a positive constant and \(\delta \in (-1,0)\) which is a measure of the degree of substitutability between principals’ outputs. \(\mathbb {E}_{t}\left( \tilde{q}_{t+1}\right) \) denotes the expectation a principal forms in t about the value of \(\tilde{q}_{t+1}\) in \(t+1\), when all production is carried out. We make the following assumption about this expectation.

Assumption 2

In each period t, each principal has a naive expectation about the aggregate quantity in the market: \(\mathbb {E}_{t}\left( \tilde{q}_{t+1}\right) =\tilde{q}_{t}\).

Assumption 2 is the simplest way of modeling adaptive expectations compared to the alternative of Bayesian learning.

The timing for the contracting-production stage in a flow period \(t, t+1\) can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

(Period t) Each agent realizes his type.

-

2.

(Period t) Principals write contracts according to their beliefs about the distribution of types and according to naive expectations about the aggregate quantity \(\tilde{q}_{t+1}\).

-

3.

(Period t) Each agent is randomly matched with a principal and the agent decides whether to accept the contract or not.

-

4.

(Period \(t+1\)) Contracts are executed and outcomes are realized and observed: profits and payments to agents are realized.

Contracts In each period t, principals write contracts which entail a rent for each quantity observed in \(t+1\). The quantities contracted in t and observed in \(t+1\) are indicated by \(\underline{q}_{t+1} \triangleq q_{t+1}(\underline{\theta })\) for the low-cost type and \(\overline{q}_{t+1} \triangleq q_{t+1}(\overline{\theta })\) for the high-cost type. We will use either of the two notations where convenient. In addition, a similar notation will hold for the transfers \(w_{t+1}(\theta )\).

We restrict our analysis to direct revelation mechanisms that are truthful. This can be done because the agent’s rent is only a function of his principal’s contract and of the aggregate quantity in the market in the previous period.

The rent is \(U\left( q_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) ,w_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) ,\theta \right) =w_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) -\theta q_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) \). Moreover, we assume that agents are protected in every state of the world by limited liability on the rent. Formally, each principal maximizes expected profits given the usual incentive (IC) and participation constraints (PC):

Recall that principals in this model use the aggregate quantity from the previous period as expectation for the next. That is, with regard to the quantity, the model we present is a cobweb model, because given the timing and the specification of the benefit function it is mathematically equivalent to a model where principals form expectations about the price instead of the quantity with a linear demand function.Footnote 6

Given the standard nature of the maximization problem the following proposition is straightforward.

Proposition 1

Given different beliefs and the same naive expectations about \(\tilde{q}_{t+1}\), the quantities for the low-cost types are equal, or \(\underline{q}_{t+1}^{v}=\underline{q}_{t+1}^{\rho }\), whereas for the high-cost type we have \(\overline{q}_{t+1}^{v}>\overline{q}_{t+1}^{\rho }\). The rent \(U(\cdot ,\overline{\theta })\) for the high-cost type is equal to zero for both types of principals, whereas for the low-cost type the rent \(U(\cdot ,\underline{\theta })\) is higher with a v-principal than a \(\rho \)-principal.

For the low-cost agent both types of principals stipulate the same, first-best quantity. However, the \(\rho \)-principal offers a smaller rent, because she mistakenly believes that there are more low-cost agents than there really are. For the high-cost type both contracts offer the same (zero) rent, but the v-principal stipulates a bigger quantity. This is so because the odds of being matched with a low-cost agent appear too large for the \(\rho \)-principal. Given that the quantity for the high-cost type is decreasing in the odds of being matched with one, the quantity of the optimistic principal is set too low.

Quantities We denote the expected quantity over the different types for a principal with belief \(\phi \) by \(\mathbb {E}_{\theta }\left[ q_{t+1}^{\phi }\left( \theta \right) \right] = v \underline{q}_{t+1}^{\phi } + (1-v) \overline{q}_{t+1}^{\phi }\) and with \(\tilde{q_t}=\int _{i} q_{t,i}\, di\) the aggregate quantity in the market, where i is an indicator of the principals in the population. Given the different proportions of principals with different beliefs, an informal appeal to the law of large numbers allows us to write the aggregate quantity as:

Profits For contracts stipulated in t, the realized profits in \(t+1\) for each \(\theta \) and for a given belief are functions \(\underline{\pi }_{t+1}\left( \tilde{q}_{t+1},\tilde{q}_{t},\phi , \underline{\theta }\right) \) and \(\overline{\pi }_{t+1}\left( \tilde{q}_{t+1},\tilde{q}_{t},\phi , \overline{\theta }\right) \). The expected profits are \(\mathbb {E}_{\theta }\left[ \pi _{t+1}\left( \tilde{q}_{t+1}, \tilde{q}_{t},\phi ,v\right) \right] \). The presence of \(\tilde{q}_{t}\) comes from the fact that each contracted quantity \(q_{t+1}\left( \theta \right) \) is a function of \(\tilde{q}_{t}\) (Assumption 2).

Proposition 2

Given different beliefs and the same naive expectations about the total quantity, for any realization \(\theta \in \left\{ \underline{\theta },\overline{\theta }\right\} \), the realized profits \(\pi _{t+1}^{\phi }\left( \cdot ,\theta \right) \) are such that:

\(\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }>\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}\) with

\(\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}\lesseqqgtr \overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }\) with

Parts of the results in Proposition 2 are a direct result from Proposition 1. Due to the fact the unbiased v-principal pays a higher rent for the low-cost agent, but produces the same quantity as the biased \(\rho \)-principal, profits must be smaller. This can be seen from Eq. (2). Further, as can be seen in Eq. (3), the difference in profits for the high-cost agent depends on the change of the quantity \(\tilde{q}\) from one period to the next. The v-principal makes a larger profit than the \(\rho \)-principal if the quantity decreases or is constant from one period to the next. The reverse is true if the change is positive and large enough.

To summarize, the basic stage game defines an aggregative game in which the profit of principals in a particular period depends on the belief about the distribution of types, the specific match and the behavior of all other principals, which affects the aggregate quantity in the market.

2.2 Evolutionary Learning by Imitation

We use a proportional imitation rule to model the replica equation ([18]). For that purpose we define the conditional switch rate, which is the probability that at the end of a period a principal changes beliefs. To do that, we periodically allow some principals at the end of a period to observe the profit of a second principal. For each principal two scenarios are possible. Either she meets a principal from the same reference group, who got matched with the same type of agent, or from a different reference group, i.e., a principal who got matched with a different type of agent.

The propensity to compare is a measure of how open a principal is toward comparing her situation to a different principal. In what follows we use the following assumption.

Assumption 3

The propensity to compare is equal to zero if the principals come from different reference groups.

Assumption 3 immensely simplifies the following exposition and analysis, and the intuitions are not hidden behind the algebra. We shall relax this assumption in Sect. 3.4.

Given the proportion of low-cost types v and the proportion \(\alpha _{t}\) of principals using v, \(P(\phi \rightsquigarrow \lnot \phi )=\alpha _{t}\left( 1-\alpha _{t}\right) \) is the probability that a principal with a belief \(\phi \) meets a principal with the different belief. Since we assume that matching between principals and different types of agents is type-independent, the probability that two principals were matched with a low-cost agent is simply \((v)^2\) and the probability that both were matched with a high-cost agent is given by \((1-v)^2\). Hence, we have the probabilities that two principals with different beliefs and in the same reference group meet:

In words, \(\gamma _{t}^{v\rho }\) is the probability that a v-principal would consider switching to belief \(\rho \), with a similar interpretation of \(\gamma _{t}^{\rho v}\). The probability of switching to the other strategy is linearly dependent on the payoff difference. Formally, it is the product \(\Omega \cdot \left[ \pi _{t+1}^{\phi }-\pi _{t+1}^{\lnot \phi }\right] \), where \(\Omega >0\) is chosen to scale the payoff difference in such a way that it can be used as a probability.

We find three mechanisms to justify why principals infer whether or not they come from the same reference group. Either because of a mechanism based on word-of-mouth communication as in Banerjee and Fudenberg [4], or because the contracts and profits are observed as in Ania et al. [1], or simply because the contracting quantities are observed, because principals with low-cost agents obtain equal quantities.

We assume that principals are memoryless about past plays or past switches and that learning takes place by imitation of other principals’ beliefs. This assumption is based on the following considerations. Information about the beliefs is shared by word-of-mouth communication (see above). Alternatively, beliefs can be inferred if the menus of contracts are observable.

Putting the pieces together, the dynamic over time is described by the following equation:

The equation should be read as follows. The fraction of v-principals in a period is equal to the fraction in the previous period plus all \(\rho \)-principals who switch to v minus all v-principals who switch to \(\rho \). From Proposition 2 we know that the term \(\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}-\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }\) can be positive or negative depending on the magnitudes and direction of fluctuations of the quantity in the market. If the term is negative the direction of proportional imitation is reversed, which means that the v-principal switches to \(\rho \) with the given probability. The resulting equation is equivalent.Footnote 7 Substituting the specific switch rates defined above, we arrive at the discrete change of \(\alpha \) from one period to the next:

2.3 Overview

To recap, the model aims at combining insights from cobweb models and the problem of asymmetric information, in particular, adverse selection outcomes. The three main assumptions we make reflect this basic goal.

Certainly, one could imagine alternatives to Assumption 1. If one assumes that all principals have the same belief (effectively, \(\rho =v\)), then Eq. (4) simply disappears and the model reverts back to a basic cobweb. If, instead of optimism, one assumed pessimism (\(\rho <v\)), all of the results presented below would be symmetrically reversed.

Assumption 2 is integral to the cobweb model reflecting a version of adaptive expectations. As discussed, rational expectations would go against the spirit of boundedly rational principals. We use naive expectations, which are the simplest version of adaptive expectations taking only one preceding period into account. For an overview of the role of expectations see Evans and Honkapohja [8].

Lastly, Assumption 3 governs the set of possible subjects for comparison for a principal. This assumption comes mainly from Selten and Ostmann [20], Selten and Apesteguia [19], whose ideas are based on behavioral studies from psychology [9] and early experimental economics Todt [21]. For the moment the propensity to compare has been set rather narrowly by allowing a principal to compare only with another principal of a different belief if they were matched with the same type of agent.

We shall return to the last two points in the discussion section.

3 Equilibria, Stability and Dynamics

The economy in our model is governed by Eqs. (1) and (4). They can be rearranged using the functional forms of the quantities and profits. The algebraic derivation can be found in Appendix “Derivation of the Nonlinear Map”.

where \(a=\Delta \theta \frac{\rho -v}{\left( 1-\rho \right) \left( 1-v\right) }\), \(b=\frac{1}{2}\Delta \theta \left( \frac{v}{1-v}+\frac{\rho }{1-\rho }\right) \) and \(c=\Delta \theta \frac{\rho -v}{1-\rho }\) are used to simplify the expressions.Footnote 8 The dynamic system described by equations (5) and (6) is a map \(X_{t+1}=\Gamma (X_t)\) where \(X_t=(\alpha _t,\tilde{q}_t)\).

3.1 Fixed Points

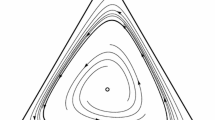

The nullclines, i.e., the loci of points where a variable does not vary from one period to the next, are plotted in Fig. 1. The dashed line gives the combination of points where \(\tilde{q}_{t+1}=\tilde{q}_t\) from Eq. (6) and all solid lines (including both vertical lines) gives the locus of points where \(\alpha _{t+1}=\alpha _t\) from Eq. (5).

Two phase diagrams with \(\alpha \) on the horizontal and \(\tilde{q}\) on the vertical axis. The dashed line shows the locus of points where \(\tilde{q}_{t+1} = \tilde{q}_t\), all solid lines show the locus of points where \(\alpha _{t+1}=\alpha _t\). Panel (a) (b) shows the case where \(k<0\) (\(k>0\)) as defined in the text. \(\tilde{q}_{high}\) (\(\tilde{q}_{low}\)) is the fixed point-quantity associated with \(\alpha =1\) (\(\alpha =0\))

To better describe the fixed points and their dependence on the beliefs, we define \(k \triangleq \left( 1-v\right) ^{2}b-v^{2}\Delta \theta \). This k determines the relative location of the nullclines. It will play a crucial role in determining the stability of the steady state. As will become clear, for \(k\ne 0\), any steady state is hyperbolic meaning that the associated eigenvalues are different from unity. For \(k<0\) (\(>0\)) the nullcline giving the steady states for the quantity \(\tilde{q}\) is below (above) the one for \(\alpha \) (see Fig. 1). The third case (not shown) is \(k=0\), when the two diagonal nullclines overlap. From Fig. 1, it is clear that the system admits two or infinitely many fixed points, where the latter occurs only when \(k=0\). Focusing on the two non-degenerate cases (where the nullclines do not overlap) we can claim:

Lemma 1

Whenever \(k=\left( 1-v\right) ^{2}b-v^{2}\Delta \theta \ne 0\), the nonlinear system admits two hyperbolic steady states \(X^{0}=\left( 0,\tilde{q}_{low}\right) \), \(X^{1}=\left( 1,\tilde{q}_{high}\right) \) with

The quantities \(\tilde{q}_{low}\) and \(\tilde{q}_{high}\) are simply the intersections of the nullcline associated with the quantity (the dashed line in Fig. 1) with the vertical parts of the nullclines for \(\alpha \). Either of the two steady states represents a population in which all principals hold the same belief. The presence of two steady states is due to the principals’ inability to update their priors in a Bayesian fashion, but rely on imitation. Therefore, in a steady state in which all principals have a given belief about the distribution, there is no learning. The aggregate quantities reflect the earlier finding in Proposition 1. There we show that being a \(\rho \)-principal means to ask a lower quantity from the high-cost type, whereas for the low-cost type both principals produce the same quantity, i.e., the commonly known result that there is no distortion “at the top” is preserved. Therefore, the aggregate quantity in the steady state \(X^0\) is lower than in \(X^1\). This leads to higher prices, which can be dubbed a “cartel of the ignorant”, because the collusion is not the result of a coordinated action, but the spillover effects of the imitative learning of its members.

Next, in order to study the stability, the Jacobians are evaluated at the steady states:

Using the usual definitions related to local bifurcations, from the Jacobians the following proposition immediately follows:

Proposition 3

Given beliefs v and \(\rho \) the following holds for the system defined in (5) and (6).

-

1.

The system has always either

-

(a)

a stable and an unstable fixed point, which are both hyperbolic (for \(k\ne 0\)), or

-

(b)

two non-hyperbolic fixed points and infinitely many fixed points (for \(k=0\)).

-

(a)

-

2.

The system has a local fold bifurcation for both fixed points if \(k=0\).

-

3.

The system undergoes a transcritical bifurcation. For \(k<0\) \(X^0\) is the stable and \(X^1\) is the unstable fixed point. It is the other way around for \(k>0\).

The local stability comes from the design of the imitation protocol involving realized payoffs. More clearly, the evolutionary pressure is not based on the mere difference in expected payoff, which is larger for the unbiased principal in the steady state, but the difference in realized payoffs has to be taken into consideration. Proposition 3 lays bare the mechanics of the exchange of stability synthesized in k. Before we get to the economic interpretation, the following subsection discusses the robustness of this finding.

3.2 Two Qualitative Remarks

First, a remark is needed concerning a possible shutdown policy of principals, which in the literature of mechanism design refers to a situation in which principals choose to write contracts only for the low-cost type (e.g., Laffont and Martimort [14], chapter 2). We make clear that a linear demand and supply function in the standard cobweb model with naive expectations lead necessarily to fluctuations in the quantity (and therefore in the price) such that negative values are unavoidable unless more restrictive assumptions are imposed. Therefore, it appears clear that high values of the quantity \(\tilde{q}_t\) in a preceding period could lead principals (who solve the maximization problem with naive expectations about \(\tilde{q}_t\)) to adopt a shutdown policy for the high-cost type. In our dynamic context, a shutdown policy would apply whenever the gain from a negotiation with this type is, in expectation, negative. We assume that in our model \(\beta \) is large enough so that this never happens.Footnote 9

Second, in the previous section we defined \(\Omega \) as a parameter needed to bound the difference in payoffs to unity such that the whole expression could be considered a probability. The following lemma shows that for a qualitative analysis this is unproblematic.

Lemma 2

For every two different \(\Omega \) and \(\Omega '\) there exists \(\Delta \theta '=\overline{\theta }'-\underline{\theta }'\) such that the system with \(\Omega \) and \(\Delta \theta \) is topologically equivalent near the steady state to the system with \(\Omega '\) and \(\Delta \theta '\).

The result in Lemma 2 implies that the normalization by the parameter \(\Omega \) is not problematic for a local qualitative analysis of the dynamic system given a rescaling of \(\Delta \theta \).

3.3 Global Behavior

Having identified the local stability of the steady state, we move from a local analysis to a global analysis of the dynamic system. Given the phase diagram of our map made of a possible saddle-sink connection, the study of convergence should be only related to the identification of the sink acting as an attractor and a saddle, with an invariant unstable manifold, acting as a repeller. As seen, this can be done easily observing that the condition \(k \triangleq \left( 1-v\right) ^{2}b-v^{2}\Delta \theta \ne 0\) implies the magnitude of the eigenvalues and therefore the topological structure of the fixed points. Therefore, any preliminary analysis should start from the relationship between the different beliefs described by k.

As is well known, a standard cobweb model generates oscillating time series, and can present a limit two cycle whenever the ratio between the slopes of the demand and supply functions are equal to \(-1\). The analogy of our set-up with the standard “stable” cobweb model is helpful in this regards (see footnote 6). The mere observation that our map describes a standard linear cobweb model with a shifting supply curve suggests a possible presence of similar patterns. Hence, the analysis should account for the existence of cycles also when the ratio between functions is not (necessarily) \(-1\).

3.3.1 Convergence to a Monomorphic State

This section analyzes the global convergence to a monomorphic state where all the principals have the same beliefs. We start with the inspection of the condition \(k \triangleq \left( 1-v\right) ^{2}b-v^{2}\Delta \theta \gtreqless 0\). If \(k=0\), it defines a critical value \(\rho ^{c}\) as a function of the true distribution \((v,1-v)\) of agents’ type in the economy. Hence, we refer to \(\rho ^{c}\) as an indicator of the degree of optimism and to overoptimistic principals, who have a belief higher than \(\rho ^{c}\). It holds that if \(\rho >\rho ^{c}\) (\(\rho <\rho ^{c}\)), then \(k>0\) (\(k<0\)). Given that the sign of k determines the magnitude of the two eigenvalues, it is sufficient to analyze how it depends on the relationship between v and \(\rho \). With this aim, we observe:

Theorem 1

Whenever some principals are optimistic, and the map \(\Gamma (X_t)\) only has the two steady states \(X^0\) and \(X^1\), the following holds:

-

1.

Whenever the proportion of low-cost agents is greater than half of the population (\(v>\frac{1}{2}\)), for all \(\rho <\rho ^{c}\) the population will converge to a state where all principals are optimistic (\(X^0\)). Conversely, for a high degree of optimism (\(\rho >\rho ^{c}\)), the population will converge to a state where all principals are unbiased (\(X^1\)).

-

2.

For \(v \leqslant \frac{1}{2}\), any \(\rho >v\) is such that \(\rho >\rho ^c\). Hence, for every \(\rho \) the population will converge to a state where all principals are unbiased (\(X^1\)).

To grasp intuition, consider (for example) the two effects of being a \(\rho \)-principal. On the one hand, a \(\rho \)-principal pays a lower informational rent. On the other hand, she reduces the quantity of the high-cost agent more. In addition, given the switching protocol, based on the reference group, the comparison between principals is undoubtedly successful for a \(\rho \)-principal matched with a low-cost agent. If \(\rho \) is not too large, the lower informational rent represents the marginal benefit, whereas the lower quantity is the marginal cost. A too high \(\rho \) (\(>\rho ^c\)) implies a too high cost. In fact, in this case, the steady state becomes unstable. An identical rationale explains the (in)stability of a steady state \(X^1\) where all principals have the unbiased belief.

If the proportion of low-cost type is small (i.e., \(v \leqslant \tfrac{1}{2}\)), then the convergence is necessarily to an unbiased case. The cost of being a \(\rho \)-principal is higher than the benefit. Moreover, as seen, \(\rho \)-principals realize a higher profit with low-cost agents. Intuitively, for v small, matches are more likely to be with a high-cost type and, therefore, \(\rho \)-principals lose their advantage.

3.3.2 A Limit-Two Cycle

In the basic cobweb model a cyclical behavior comes from the fact that demand and supply have identical (in absolute value) slopes and that suppliers have naive expectations about the next period’s aggregate quantity. In our variant of the cobweb model, this can be induced despite the fact that the underlying cobweb model is stable, because shifting the supply function can induce a cyclical pattern.Footnote 10 Given two states \(X^{\prime }=(\alpha ^{\prime },\tilde{q}^{\prime })\) and \(X^{\prime \prime }=(\alpha ^{\prime \prime },\tilde{q}^{\prime \prime })\) in two different generic time periods, a limit two cycle is defined as:

The following theorem gives conditions under which this can occur.

Theorem 2

All else equal, a necessary condition for the existence of limit-two cycles for the map \(\Gamma \left( X\right) \) is that \(\delta \) is sufficiently small or \(\Delta \theta \) is sufficiently large.

In the standard cobweb model, fluctuations are present and come from the expectation about the aggregate. The evolutionary learning in our model adds an additional factor which influences the supply curve. More precisely, the polymorphic configuration synthesized in \(\alpha \) implies a shift of the supply. If \(\delta \) increases, the demand function becomes flatter making the cobweb stable. Nevertheless, a large enough difference in abilities (measured as the difference in the agents’ marginal costs \(\Delta \theta \)) implies larger shifts in the supply over time, which can then again create cyclical patterns. Depending on the interplay between the two parameters \(\delta \) and \(\Delta \theta \), our model can generate more than one limit-two cycle without assuming equal slopes.

3.4 Discussion

Before we conclude, we would like to return to some of the assumptions made in the model and discuss their implications.

First, the assumption of optimism (Assumption 1) can be reversed. If one assumes pessimism, all findings presented so far will be symmetrically reversed, as well. This implies, for example, for one of the main results in Theorem 1 that there exists a level of pessimism below which (overly pessimistic principals) the population converges to an unbiased equilibrium. The opposite holds when this threshold is not passed.

Second, Assumption 3 about the reference groups for comparison can be relaxed. So far, we have only considered the reference group including all the principals who were matched with the same type. However, it is readily possible to assume that also a reference group with other principals can play a role in the imitation. In this case, the general formalization of the model includes a probability, \(\xi \), representing the propensity to compare. This implies that principals are not precluded from comparing themselves with any other principals independent of the match. Technically, this would change the value of the composite parameter k to a new value \(\tilde{k}\).Footnote 11 In our model so far the propensity to compare with a different type-matching principal is set equal to zero. If this is not the case, the result of our main theorem would slightly change. This can be summarized in the following.

Corollary 1

Whenever an optimistic or pessimistic bias is present and the propensities to compare are different, there is a critical value \(\tilde{k}\) such that for \(\tilde{k}<0\), the population converges to a monomorphic biased state.

As we have seen, in the absence of a cycle, the economy converges to one of the two steady states according to the degree of optimism: a high degree leads to the unbiased equilibrium. Enlarging the set of possible references, i.e., increasing \(\xi \), leaves the structure of the results intact. Whenever the propensity to compare with different matches increases the over-optimism threshold decreases.

The model presented is very much in the tradition of approaches modeling boundedly rational individuals’ imitation (see Schlag [18] and references therein). Put simply, in all of these approaches, individuals use a version of comparing realized profits. This is true also for our model whenever \(\xi <1\). For completeness’ sake, if all principals are potential objects for comparison independent of the match (\(\xi = 1\)), the threshold disappears, and the steady state \(X^0\) (all biased) loses stability. The rationale for this finding is based on the characterization of the resulting protocol in this extreme case. Mathematically, the proportional expected protocol is linear in payoff differences. Consequently, if principals are open to comparing their expected (hypothetical) profit with a randomly matched principal, this would de facto lead to a situation where each principal linearly compares her (expected) profit to the average profit in the markets. Under this scenario, every steady state with a biased belief is unstable with respect to a perturbation with some principals using the true belief. Moreover, the naive expectation assumption (Assumption 2) also gives rise to a linear nullcline describing the evolution of the quantity. The last two points and the absence of stochastic perturbations lead to a case where the nullclines in our phase diagram do not present interior intersections and, therefore, no interior steady states. Whereas our paper aims to provide a simple intuition on how the imitative dynamic affects results under adverse selection, it appears interesting for future research to include more sophisticated learning procedures and alternative imitative protocols (see, e.g., Schlag [18] and Sandholm [16] for discussions about imitative protocols, Evans and Honkapohja [8] for the role of expectation and, Schlag [18] and Hommes [12] for alternative expectation modeling with bounded and behavioral rationality).

In addition, we assume that there are just two types of agents, whereas the mechanism design literature allows also for a continuity of types. From a formal point of view, it is possible to include continuity of abilities. Then, the belief of the biased principal is represented by a cumulative distribution function, which is first-order-stochastic dominated by the true one. In order to allow a comparison between principals one should define a norm for each matched ability level. This would clearly add complexity to the algebra of the model, but would not add anything of substance to our results.

4 Conclusion

Our paper introduces an evolutionary learning model with beliefs into a market characterized by an adverse selection problem. We relax the common assumption of homogeneous beliefs: principals have one of two possible beliefs about the distribution of the ability of agents in the sense that some overestimate the true fraction of low-cost agents. In our model, the evolutionary learning takes place in the form of a non-Bayesian updating characterized by imitation. The higher the fraction of principals with a particular belief and the higher the payoff difference between two randomly chosen principals, the higher the probability to switch to this belief. We study convergence toward different compositions of the population showing how heterogeneity drives the economy toward possibly different equilibria.

We show that if the bias is relatively moderate, the learning process leads to a uniformly biased population. The reverse is true for large biases. The model hones in on the externality of a learning process as the decision to update one’s beliefs impacts other market participants. The interplay between quantity decisions based on beliefs, on the one hand, and the effect biased beliefs have on aggregate market outcomes, on the other hand, raises new questions to study in competitive markets.

Notes

The analysis is carried out with the assumption of an optimistic bias. A pessimistic bias would lead to a specular model with specular results.

This is different from Arifovic and Karaivanov [3], who start from an adverse selection model evolving over time assuming that principals are unable to solve the correct maximization problem.

There is a complementary behavioral approach to our set-up in Esponda [7] and Frick et al. [10]. They go in the direction of aggregation under misperception where actors would attempt to estimate an aggregate (footnote 4 continued) ignoring the effect of biased choices. In our behavioral approach, evolution is not driven by an incomplete estimation but by imitation.

Including the belief which turns out to be the true one (and not assuming a situation characterized by two biases) is less restrictive and comes from the aim of showing convergence toward a biased belief, and a possible coexistence of beliefs. A situation with two biases would mean, therefore, assuming that such convergence has already happened. However, a model with only biased beliefs would not substantially change the dynamic.

This equivalent model can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Each principal maximizes:

$$\begin{aligned} \underset{\{\underline{q}_{t+1},\underline{w}_{t+1},\overline{q}_{t+1}, \overline{w}_{t+1}\}}{\max }\phi \left\{ \mathbb {E}_{t}\left[ P_{t+1}\right] \underline{q}_{t+1}-\tfrac{\underline{q}^2_{t+1} }{2}-\underline{w}_{t+1}\right\} +\left( 1-\phi \right) \left\{ \mathbb {E}_{t}\left[ P_{t+1}\right] \overline{q}_{t+1}-\tfrac{\overline{q}^2_{t+1}}{2} -\overline{w}_{t+1}\right\} \end{aligned}$$under (ICs) and (PCs), and therefore a linear supply function is obtained.

-

2.

Principals have naive expectations about the price: \(\mathbb {E}_{t}\left[ P_{t+1}\right] =P_{t}\).

-

3.

The demand is linear: \(Q_{t+1}=A-BP_{t+1}\).

-

4.

Market clears: the prices are computed on the demand function.

The connection to our model is established for \(\beta =\frac{A}{B}\) and \(\delta =-\frac{1}{B}\). Our choice of the interval for \(\delta \in (-1,0)\) defines a standard stable cobweb model (in the absence of any kind of heterogeneity of expectations about any variable). See Hommes [12] for an overview and a recent reapprecitation of the cobweb model.

-

1.

To see this, write the dynamic for \(\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}<\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }\) as \(\alpha _{t+1}=\alpha _{t}-\gamma _{t}^{\rho v}\{ \Omega [\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }-\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}]\}-\gamma _{t}^{v\rho } \{\Omega [\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }-\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}]\}\), which is equivalent.

To ensure that \(\alpha \) never leaves the unit interval the long form of Eq. (5) should be written as: \(\alpha _{t+1}=\min \{ 1,\max \{ \alpha _{t}+\alpha _{t}\left( 1-\alpha _{t}\right) a\Omega \{ \left( 1-v\right) ^{2} \{ \delta \left[ \beta -\overline{\theta }+(\delta -1)\tilde{q}_{t}- \left( 1-\alpha _{t}\right) c\right] +b \} -v^{2}\Delta \theta \} ,0 \} \}.\)

Alternatively this could be dealt with by assuming that in some periods (given some wide fluctuation of the quantity) only contracts for low-cost types are offered. This would imply possible lag periods, in which only principals who got matched with a low-cost agent consider switching. The results would be essentially the same only complicating the calculus.

In our model \(\delta \) is the ratio between the slope of the demand and supply function, where we normalize the slope of the latter to 1. Therefore, if \(\left| \delta \right| =1\), we would have the standard limit-two cycle for the aggregate quantity. See also footnote 6.

The change in the reference group would change Eq. (4) in the following way. With \(\xi \) as the propensity to compare with principals with a different match: \(\alpha _{t+1}=\alpha _{t}+\alpha _{t}(1-\alpha _{t}) \Omega ((1-v)^{2}[\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}-\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }]-v^{2}[\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }-\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}] + \xi \{v(1-v)[\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}-\overline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho }]-v(1-v) [\underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{\rho } - \underline{\pi }_{t+1}^{v}]\}) \). The critical k then changes to \(\tilde{k} = k+\xi v(1-v)(b-\Delta \theta )\).

References

Ania AB, Tröger T, Wambach A (2002) An evolutionary analysis of insurance markets with adverse selection. Games Econ Behav 40(2):153–184

Apesteguia J, Huck S, Oechssler J (2007) Imitation-theory and experimental evidence. J Econ Theory 136(1):217–235

Arifovic J, Karaivanov A (2010) Social learning in a model of adverse selection. In: Industrial organization, trade and social interaction: essays in Honour of B. Curtis Eaton. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Banerjee A, Fudenberg D (2004) Word-of-mouth learning. Games Econ Behav 46(1):1–22

Björnerstedt J, Weibull JW (1996) Nash equilibrium and evolution by imitation. In: Arrow KJ, Colombatto E, Perlman M, Schmidt C (eds) The rational foundations of economic behavior. Macmillan, Houndmills, pp 155–171

de la Rosa LE (2011) Overconfidence and moral hazard. Games Econ Behav 73(2):429–451

Esponda I (2008) Behavioral equilibrium in economies with adverse selection. Am Econ Rev 98(4):1269–91

Evans GW, Honkapohja S (2001) Learning and expectations in macroeconomics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 7(2):117–140

Frick M, Iijima R, Ishii Y (2020) Stability and robustness in misspecified learning models. Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper, 2235

Gervais S, Goldstein I (2007) The positive effects of biased self-perceptions in firms. Rev Finance 11(3):453–496

Hommes CM (2013) Behavioral rationality and heterogeneous expectations in complex economic systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kuznetsov YA (1998) Elements of applied bifurcation theory. Springer, New York

Laffont J-J, Martimort D (2002) The theory of incentives: the principal-agent model. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Rothschild M, Stiglitz JE (1976) Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information. Q J Econ 90(4):629–649

Sandholm WH (2011) Population games and evolutionary dynamics. MIT Press, Cambridge

Santos-Pinto L (2008) Positive self-image and incentives in organisations. Econ J 118(531):1315–1332

Schlag KH (1998) Why imitate, and if so, how? J Econ Theory 78(1):130–156

Selten R, Apesteguia J (2005) Experimentally observed imitation and cooperation in price competition on the circle. Games Econ Behav 51(1):171–192

Selten R, Ostmann A (2001) Imitation equilibrium. Homo oeconomicus 18(1):111–149

Todt H (1972) Pragmatic decisions on an experimental market. In: Sauermann H (ed) Contributions to experimental economics, pp 608–634

Vega-Redondo F (1997) The evolution of Walrasian behavior. Econometrica 65(2):375–384

Vives X (2001) Oligopoly pricing: old ideas and new tools. MIT Press, Cambridge

Wang J, Zhuang X, Yang J, Sheng J (2014) The effects of optimism bias in teams. Appl Econ 46(32):3980–3994

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful to seminar participants at the University of Tartu, the University of Marburg, EBS Business School, and the EARIE conference in Munich with a previous version. We thank an associate editor and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments and remarks, which helped us greatly improve the exposition of the paper.

A Appendix

A Appendix

1.1 A.1 Proof of Proposition 1

As is standard (see, e.g., Laffont and Martimort [14]), the participation constraint of the low-cost type is implied by PC(\(\overline{\theta }\)) and IC(\(\underline{\theta }\)). The incentive constraint of the high-cost type is slack at the optimum. Moreover, the other two are binding constraints. Then, using the binding constraints to substitute wages in the objective function, the maximization problem reads as follows:

The quantities at the optimum are defined implicitly by: \(S_{\underline{q}}^{\prime }(\cdot )=\underline{\theta }\), \(S_{\overline{q}}^{\prime }(\cdot )=\overline{\theta }+\frac{\phi }{1-\phi }\Delta \theta \). Substituting for \(\mathbb {E}_{t}(\tilde{q}_{t+1})=\tilde{q}_{t}\) and using the specific functional form for \(S(\cdot )\), we obtain that in any generic time the quantities set by principal are:

From \(\rho >v\), follows: \(\underline{q}_{t+1}^{v}=\underline{q}_{t+1}^{\rho }>\overline{q}_{t+1}^{v}>\overline{q}_{t+1}^{\rho }\).

The binding PC\((\overline{\theta })\) clarifies that the high-cost types realize a zero rent independently from the principal they are matched with. Conversely, from the binding IC\((\underline{\theta })\), we have that the rent of the low-cost types \((\text {rent}^\phi _{t+1}(\underline{\theta }))\) differs according to the principals’ belief. It holds:

and therefore \(\text {rent}^v_{t+1}(\underline{\theta })>\text {rent}^\rho _{t+1}(\underline{\theta })\).

1.2 A.2 Proof of Proposition 2

Recall that principals design contracts based on the belief \(\mathbb {E}_{t}(\tilde{q}_{t+1})=\tilde{q}_{t}\); meaning that in a generic time t contracts are defined on the basis of quantities as in (A.2) and (A.3). Hence, their choices about quantities in a time \(t+1\) are based on the belief about the aggregate quantity, which in our set-up equals the quantity one period before \(\tilde{q}_{t}\). However, in \(t+1\) the payoff is affected by the realization of the aggregate quantity \(\tilde{q}_{t+1}\) which is described by (1).

To compute the differences in payoffs, it is useful computing the difference in quantities for the high-cost type. From Eq. (A.3) we obtain: \(\overline{q}_{t+1}^{v}-\overline{q}_{t+1}^{\rho }=\Delta \theta \left[ \frac{\rho }{1-\rho }-\frac{v}{1-v}\right] \). We have that for a match with a low-cost type the quantity for both principals is equal. Hence, the surpluses are equal and the only difference is in the paid informational rent. It follows:

which is Eq. (2) in the paper.

Conversely, for a match with a high-cost type

which is Eq. (3) in the text.

1.3 A.3 Derivation of the Nonlinear Map

We start by computing the equation describing the evolution of the aggregate quantity over time. From (1), we know:

Using (A.2) and (A.3), we compute \(\mathbb {E}_{\theta }[q_{t+1}^{v}(\theta )]\) and \(\mathbb {E}_{\theta }[q_{t+1}^{\rho }(\theta )]\), where the expectation is w.r.t. the true realization of the variable \(\theta \) (i.e., the distribution for which it holds \(Pr(\theta =\underline{\theta })=v\)).

and

with \(c=\Delta \theta \frac{\rho -v}{1-\rho }\) as defined in the text.

Using (A.8) and (A.9) in (A.7), it is immediate to obtain:

which is Eq. (6) in the paper. Subtracting \(\tilde{q}_{t}\) to both sides of this equation, we obtain:

Substituting (A.11) in Eq. (A.6) to eliminate its dependence on \(\tilde{q}_{t+1}\) gives the difference in realized payoffs:

Then, using both differences in realized payoffs (A.5 and A.12) in the replica equation (4), we obtain (5).

1.4 A.4 Proof of Proposition 3

The proof involves a simple inspection of the eigenvalues of the Jacobians. The two eigenvalues are \(\delta \) and \(1\pm a\Omega k\). Then, for \(k=0\) one eigenvalue crosses the unit circle for both points (fold bifurcation). Moreover, for k changing sign one point has both eigenvalues smaller than one, whereas the other becomes a saddle point exchanging stability (transcritical bifurcation). This implies that for \(k<0\) the point \(X^0\) is a stable hyperbolic steady state, which corresponds to the situation depicted in Fig. 1a. Accordingly, the reverse case of \(k>0\) is shown in Fig. 1b, in which \(X^1\) is stable.

1.5 A.5 Proof of Lemma 2

The following proof works on the basis of the center manifold theorem. The theorem claims that whenever the system is close enough to a steady state, the stable and unstable manifolds are tangent to the respective stable and unstable eigenvectors of the linearized system (see, e.g., Kuznetsov [13] page 157). Given the theorem, the proof can be formulated as follows. Given the Jacobians in the steady state, the two eigenvalues are \(\delta \) and \(1\pm a\Omega k\). Since \(\left| \delta \right| <1\), the corresponding eigenvectors are the stable ones, they are invariant and correspond to the vertical line in \(\alpha =0\) and \(\alpha =1\). Then, for an \(\Omega '\) it is sufficient to define a rescaling of \(\Delta \theta \) such that \(a\Omega k=a'\Omega 'k'\). The rest follows from the center manifold theorem.

1.6 A.6 Proof of Theorem 1

The proof is based on the results of Proposition 3, and therefore, it requires to identify the stable and unstable fixed points. As seen, the stability of the steady states depends on the sign of k. Whenever the proportion of low-cost agents is greater than half of the population (\(v>\frac{1}{2}\)), k can be greater than, smaller than or equal to zero. Recall that \(k=0\) is satisfied for \(\rho =\rho ^{c}\) and that the sign of k depends on the relation between \(\rho \) and \(\rho ^c\). If \(\rho >\rho ^{c}\) then \(k>0\) and, therefore, from Proposition 3 the fixed point \(X^{1}\) is a sink and \(X^{0}\) is a saddle node; the opposite is true for \(\rho <\rho ^{c}\), which implies that \(k<0\). Hence, given that there are only two fixed points, one stable and the other unstable, for any initial state the population converges to the stable one.

It remains to prove that for \(v \leqslant \tfrac{1}{2}\) for every \(\rho >v\) it follows \(\rho >\rho ^c\) and, therefore, that \(X^{1}\) is the sink. In fact, solving \(k=0\) to obtain \(\rho ^c\), we have:

The function \(\rho ^c(v)\) in the interval \(v\in [0,\tfrac{1}{2}]\) has a unique minimum, and therefore, it is U-shaped. Moreover, it holds \(\rho ^c(v=0)=\rho ^c(v=\tfrac{1}{3})=0\). Hence, for \(v\in [0,\tfrac{1}{3})\) it holds that \(\rho ^c<0\) and therefore every \(\rho>0>\rho ^c\). Conversely, for \(v\in (\tfrac{1}{3}, \tfrac{1}{2}]\) it holds that \(\rho ^c(v)\) is increasing, but \(\rho ^c(v=\tfrac{1}{2})=\tfrac{1}{2}\). Hence, the function \(\rho ^c(v)\) is always below the straight line v and therefore every \(\rho >v\) it also such that \(\rho >\rho ^c\).

1.7 A.7 Proof of Theorem 2

The aim is to show that there can exist a limit-two cycle. Hence, we will proceed in computing the second iterate for the equations describing the evolution of the aggregate quantity and the fraction \(\alpha \). Then, we will show that the conditions (\(\delta \) relatively small or \(\Delta \theta \) relatively large) as in the theorem ensure the existence of the limit-two cycle.

To simplify the algebra, let \(R\equiv a\Omega \left( 1-v\right) ^{2}\frac{\delta }{1+\delta }c\) and \(S\equiv a\Omega k\). From Eq. (6), recursively, we compute the second iterate, i.e., \(\tilde{q}_{t+2}\) as only dependent on \(\tilde{q}_t\). With \(q^{\left( 2\right) } \) we denote the solution imposing \(\tilde{q}_{t+2}=\tilde{q}_{t}\) which is equal to:

Inserting (A.13) in (5), and simplifying using the expressions for R and S, we can write:

The same relationship holds for \(\alpha _{t+1}\), \(\alpha _{t+2}\):

To simplify the algebra (and, more importantly, the subsequent analysis) even further, we will use the following substitution:

With this last equation, it is helpful to rewrite (A.14) as:

To reduce the amount of computations, we will write:

Substituting (A.16) in (A.15):

We denote with \(\alpha ^{(2)}\) the steady state of the second iterate, i.e., \(\alpha ^{(2)} \equiv \alpha _{t+2}=\alpha _{t}\). Hence, dividing the previous equation by \(\alpha ^{(2)}\), we can write:

Adding and subtracting in the last bracket L/H and collecting common factors:

This last expression can be simplified, obtaining:

Using the expression for L and simplifying:

Factoring and recalling the expression for H, we write:

Equations (A.17) and (A.18) determine \(\alpha ^{\left( 2\right) }\), (A.14) determines \(\alpha _{t+1}\) and (A.13) determines \(q^{\left( 2\right) }\).

Equation (A.13) has an unique solution for \(q^{(2)}\). The solutions for \(\alpha ^{\left( 2\right) }\) are not easily obtainable, and they can be in the set of complex numbers. Hence, in what follows, we discuss the conditions leading to real solutions. Equations (A.17) and (A.18) define a polynomial of degree 6 for \(\alpha ^{(2)}\). Observe that \(\delta \rightarrow -1\) implies \(R \rightarrow -\infty \). It follows that (independently of \(\Delta \theta \)) H from (A.18) can be sufficiently negative to allow for the LHS of (A.17) to be negative and therefore potentially ensure real solutions for \(\alpha ^{(2)}\). Conversely, suppose \(\delta \) is sufficiently large; we show that also \(\Delta \theta \) sufficiently large ensures the existence of a solution. Equations (A.17) and (A.18) describe a function of \(\alpha ^{(2)}\), say, \(f(\alpha ^{(2)})\). We have to prove that \(f(\alpha ^{(2)})=0\) is possible. With this aim, observe that \(\lim _{\alpha ^{(2)} \rightarrow 0}f(\alpha ^{(2)})=2+S\) and \(\lim _{\alpha ^{(2)} \rightarrow 1}f(\alpha ^{(2)})=2-S\), implying that there is at least one solution whenever \(\vert S \vert >2\). Notice that the sign of k does not depend on \(\Delta \theta \), and it is straightforward to see that \(S\equiv a\Omega k \propto (\Delta \theta )^2 \). It follows that the value of \(\Delta \theta \) can be chosen large enough to ensure \(\vert S \vert >2\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buchen, C., Palermo, A. Adverse Selection, Heterogeneous Beliefs, and Evolutionary Learning. Dyn Games Appl 12, 343–362 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13235-021-00396-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13235-021-00396-x