Abstract

Background

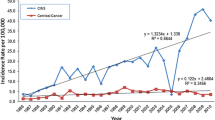

An Operational Framework document for population-wide screening of common cancers in India was launched in 2016. The target age for screening is 30–65 years for cervical, breast and oral cancers. This study was designed to review the frequency and distribution of cervical lesions among women aged 21–29, 30–65 and > 65 years.

Study Design

A retrospective review of all satisfactory cervical smears (n = 79,896) received over a ten-year period (2010–2019) was conducted. Three age bands were defined: 21–29 years, 30–65 years and > 65 years. The frequency and distribution of the various epithelial cell abnormalities (ECAs) across the three age bands were calculated. Cytohistologic correlation was performed wherever available.

Results

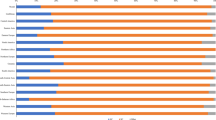

Of the 1357 ECAs (1.7% of all smears), about 16.9% were seen in the age band 21–29 years, while 4.5% presented in > 65 years of age. About 80% of the ECAs seen in younger women were low-grade squamous lesions, while 75% of lesions in women > 65 years were high-grade squamous abnormalities. Among the total 512 significant high-grade and malignant (squamous and glandular) lesions, 5.6% presented in women 21–29 years, while 10.1% were seen in > 65 years of age.

Conclusion

Majority of the significant cervical lesions would be detected if the screening focuses on the 30–65 years age group. However, about 19% of high-grade squamous preneoplastic lesions (ASC-H/ HSIL) and 13% of preneoplastic glandular lesions (AGC-N) are likely to be missed if women 21–29 years and > 65 years are excluded. The cost of screening incurred by including these age groups has to be weighed against the benefits derived, especially in low-resource settings. In the absence of universal implementation of HPV immunization, there is a felt need to enhance cervical cancer awareness and encourage screening, more so in high-risk category and symptomatic females beyond the selected age group.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN). Estimated number of cancer cases in 2020, India. Lyon: IARC; 2020 (https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/356-india-fact-sheets.pdf). Accessed Mar 04 2021.

Operational Framework. Management of Common Cancers. Available from http://cancerindia.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Operational_Framework_Management_of_Common_Cancers.pdf. Accessed Oct 27 2020.

Patel A, Galaal K, Burnley C, et al. Cervical cancer incidence in young women: a historical and geographic controlled UK regional population study. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1753–9.

Lau HY, Juang CM, Chen YJ, et al. Aggressive characteristics of cervical cancer in young women in Taiwan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107:220–3.

Spanos WJ Jr, King A, Keeney E, et al. Age as a prognostic factor in carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:66–8.

Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–9.

Nayar R, Wilbur DC, editors. The bethesda system for reporting cervical cytology: definitions, criteria, and explanatory notes. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2015.

Kurman RI, Norris HL, Wilkinson EL. Tumors of the Cervix, Vagina and Vulva. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1992. p. 48–51.

Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version. www.OpenEpi.com, accessed Oct 27 2020.

ASCCP Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. Available at: https://www.asccp.org/screening-guidelines Accessed Oct 27 2020.

WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94830/9789241548694_eng.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed Oct 27 2020.

ISCCP Cancer Screening. Available at: https://isccp.in/a-guide-to-cervical-cancer-screenings-at-every-age/ Accessed Oct 27 2020.

FOGSI GCPR on Screening & Management of Cervical Precancerous Lesions. Available at: https://www.fogsi.org/fogsi-gcpr-on-screening-mangement-of-cervical-precancerous-lesions/ Accessed Oct 27 2020.

Gupta R, Gupta S, Mehrotra R, Sodhani P. Cervical cancer screening in resource-constrained countries: current status and future directions. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:1461–7.

Bekos C, Schwameis R, Heinze G, et al. Influence of age on histologic outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during observational management: results from large cohort, systematic review, meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6383.

Benard VB, Watson M, Castle PE, et al. Cervical carcinoma rates among young females in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1117–23.

Kong Y, Zong L, Yang J, et al. Cervical cancer in women aged 25 years or younger: a retrospective study. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:2051–8.

Akinfolarin AC, Olusegun AK, Omoladun O, et al. Age and pattern of Pap smear abnormalities: implications for cervical cancer control in a developing country. J Cytol. 2017;34:208–11.

Gumpeny N, Nirmala DA. Pattern of cervical lesions, with emphasis on precancer and cancer in a tertiary care hospital of southern India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2015;3:1122–4.

Health Nutrition and Population Statistics by Wealth Quintile: Median age at first birth (women ages 25–49 years). Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=312&series=SH.FPL.FBRT.Q1.ZS. Accessed Oct 27 2020.

Díaz Del Arco C, Jiménez Ayala B, García D, et al. Distribution of cervical lesions in young and older women. Diagn Cytopathol. 2019;47:659–64.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Sanjay Gupta is a Scientist G & Coordinator in Division of Cytopathology, ICMR-National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, R., Sharda, A., Kumar, D. et al. Cervical Cancer Screening: Is the Age Group 30–65 Years Optimum for Screening in Low-Resource Settings?. J Obstet Gynecol India 71, 530–536 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-021-01479-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-021-01479-w