Abstract

Using individual data from PIAAC and data on youth unemployment for 18 countries, we test how macroeconomic conditions experienced at age eighteen affect the following decisions in post-secondary and tertiary education: (i) enrollment (ii) dropping-out, (iii) type of degree completed, (iv) area of specialization, and (v) time-to-degree. We also analyze how the effects vary by gender and parental background. Our findings differ across geographies (Anglo-Saxon, Southern European, Western European, and Scandinavian countries), which shows that the impacts of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions depend on context, such as labor markets and education systems. By analyzing various components of higher education together, we are able to obtain a clearer picture of how during economic downturns potential mechanisms interact to determine higher education decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Business cycles impact individuals in profound ways. Among the most widely studied effects of recessions are the ones on educational and labor market outcomes, because economic downturns alter the opportunity costs between education and labor market participation. However, while there exists a sizable literature that has studied the impact of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions for single countries, there is a lack of comparative cross-country studies and in particular regarding multiple higher education decisions which are potentially related.

The current paper tests how macroeconomic conditions experienced at age eighteen affect a variety of decisions in post-secondary and tertiary education. To this end, we merge data for 18 countries from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) on individuals aged 25 to 50 with data on youth unemployment for 1980–2005, the years these individuals turned eighteen. Apart from demographic controls and some variables on family background, PIAAC provides measures for cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. Hence, our estimations compare individuals of similar family backgrounds and abilities, and we test how macroeconomic conditions experienced at age eighteen affect the following higher education decisions: (i) enrollment (ii) dropping-out, (iii) type of degree completed, (iv) area of specialization, and (v) time-to-degree. Given a natural path through high school determined largely by age, this “treatment” can be considered exogenous. Conditional on various detailed controls, our estimates hence provide the causal impact of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions.

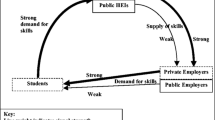

When youth unemployment increases, the opportunity cost of continued schooling falls. Everything else equal this should result in increased enrollment. Likewise, if higher education is a way to signal quality to potential employers, we would expect more individuals to enroll when labor markets are tighter. On the other hand, if individuals believe that high unemployment situations will outlast their time in higher education, they may perceive a lower expected return and choose not to enroll. Additionally, economic downturns can also reduce one’s ability to pay for higher education.

However, ability to pay could not only affect enrollment but also the probability of college completion if poor macroeconomic conditions persist. In addition, if enrollment increases due to poor labor market prospects, then the marginal student who enrolls is most likely less prepared for college. We would therefore observe lower completion rates as more students drop out. On the other hand, if enrollment falls during recessions, the remaining students may be those best prepared, and dropout rates could be lower and degree completion rates higher.

Beyond enrollment and dropout behavior, other higher education decisions could be affected by macroeconomic conditions. For example, college major choice could be altered if students use their specialization to signal employability in a tight labor market. Time-to-degree can also be affected if students are able to remain in college to “wait out the storm.” These decisions may be interconnected should the choice of major also impact time-to-degree.

Our results highlight different mechanisms at work across different geographies. For Anglo-Saxon countries, among those experiencing high youth unemployment at age 18, we estimate lower rates of bachelor’s and master’s degree completion, with neutral-to-positive estimates for the completion of any post-secondary degree (including vocational degrees). This is paired with no impacts on enrollment or dropping out of post-secondary programs. Taken together, during economic downturns, as financial constraints tighten, relatively more students seem to opt for professional rather than more expensive bachelor’s degrees.

In Southern Europe, on the other hand, where tuition fees for higher education tend to be lower, we find results consistent with reduced opportunity costs of studying during recessions. For individuals experiencing higher youth unemployment at age eighteen, we estimate an increase in enrollment with mixed outcomes. We see a higher probability of completing any post-secondary degree (including vocational, bachelor’s and master’s degrees or higher) as well as an increase in dropout rates. We also find an increase in STEM (Science Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) specializations.

Our results for Western Europe are similar to those for Anglo-Saxon countries, and we also find that higher unemployment rates experienced at age 25, i.e., 7 years later, result in longer time-to-degree. This could be indicative of individuals choosing to “wait-out” difficult macroeconomic times by remaining longer in higher education.

Finally, for Scandinavian countries, we observe reduced enrollment, lower degree completion rates, and shorter time-to-degree for those experiencing higher youth unemployment at age 18. This is in line with reduced ability to pay or lower perceived future returns to higher education playing a larger role than reduced opportunity costs. Initially, this finding may seem counterintuitive because universities in Scandinavian countries generally charge no tuition fees, and states tend to provide additional financial aid for those pursuing higher education. However, Scandinavian countries are also characterized by individuals leaving the parental home at very young ages, relatively high costs of living as well as some of the lowest contributions from family toward financing higher education (Orr et al. 2008; Schnitzer and Zempel-Gino 2002; Schnitzer et al. 2005). As a result, in Finland, Norway, and Denmark the share of students who claim that they work to cover living costs and that without their paid job they would not be able to afford their education is well above the European average (see Eurostat 2020; Masevičiūtė et al. 2018).

We also test for the heterogeneity of our findings along gender and parental background. Results differ across geographies. For instance, in Southern Europe, increased enrollment and dropout rates for individuals experiencing higher youth unemployment at age 18 are driven by women, while men are behind the positive effects on STEM specializations. For Southern European, Western European, and Anglo-Saxon countries, we find that in particular individuals from more advantageous family backgrounds are able to “wait-out” poor labor market prospects in graduate programs.

Our different results across the four geographies highlight the importance of analyzing the effects of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions for different education systems and labor markets. In addition, by looking at various components of higher education together, we are able to obtain a clearer picture of how during economic downturns potential mechanisms linked to lower opportunity costs of education and reduced ability to pay interact to determine higher education decisions. Finally, the use of PIAAC data allows us to control for individuals’ abilities, which are important determinants of higher education decisions but are often not included in other datasets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: The next section provides background information on the existing literature as well as on the institutional context of higher education in our four geographies. Section 3 describes our data, and in Sect. 4 we outline our empirical strategy. Section 5 presents and discusses our results including robustness checks and heterogeneity analyses. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Background

2.1 Literature review

While there exists clear evidence that graduating during a recession has negative lasting impacts on wages and employment (e.g., Kahn 2010; Oreopoulos et al. 2012; Oyer 2006; Raaum and Røed 2006), literature on the recession effects on higher education decisions is less conclusive.Footnote 1

Most studies have focused on the impact of macroeconomic conditions on college enrollment in the USA, finding it to be countercyclical [see, for instance, Dellas and Koubi (2003) and Clark (2011)]. Our results for Anglo-Saxon countries show no notable enrollment effects for post-secondary programs, but we find evidence consistent with a shift from bachelor’s and master’s toward professional degrees. This “downgrading” is in line with findings in Long (2015) who estimates that the Great Recession in the USA resulted in overall higher college enrollment, but decreased full-time and increased part-time enrollment, or Betts and McFarland (1995) who found that as unemployment rose in the US during the 1970-80s, enrollment in particular in less expensive community colleges increased.

Sakellaris and Spilimbergo (2000) look at foreign students at US universities and find that those from OECD countries exhibited countercyclical enrollment, fitting the opportunity cost story, whereas students from non-OECD countries exhibited pro-cyclical enrollment, fitting the ability to pay mechanism. While their study motivates the importance of looking at different country contexts, its external validity is limited by the particularly selected set of students who choose to study abroad. Nonetheless, the study clearly highlights the two main theoretical mechanisms through which recessions may impact college enrollment: opportunity costs and ability to pay.

In addition, the impact of macroeconomic conditions on enrollment has been found to vary by race (e.g., Dellas and Sakellaris 2003; Kane 1994), as well as by gender and across degree levels. Bedard and Herman (2008) find graduate school enrollment to be acyclical for women and the effect for men to vary by type of degree. In contrast, Johnson (2013) estimates graduate school enrollment to be countercyclical for women and acyclical for men. For Southern Europe, we also find countercyclical enrollment in post-secondary programs for women and acyclical enrollment for men. Considering family background, Christian (2007) finds that during US recessions college enrollment increases, but that this occurs more so among individuals from families with fewer liquidity constraints whose ability to pay is less affected.Footnote 2

Regarding other higher education decisions such as degree completion, the evidence is even less conclusive. Charles et al. (2015) find lower degree attainment after the Great Recession driven by reductions in enrollment during the previous housing boom. Kahn (2010) on the other hand provides evidence for small increases in college completion rates for US students linked to high unemployment experienced at age 18.Footnote 3 Likewise, Boffy-Ramirez et al. (2013) find degree completion to be countercyclical, with increases driven in particular by students in the 60th to 80th ability quantiles.

For countries other than the USA, Ayllon and Nollenberger (2016) find that during the Great Recession in Europe higher unemployment rates coincided with higher enrollment and small increases in completion rates. While the study by Arellano-Bover (2020) focuses on the effect of macroeconomic conditions on skill acquisition, the author also estimates increases in higher education attainments for those experiencing higher unemployment when young.Footnote 4 Similarly, Sievertsen (2016) also finds for Denmark that post-secondary enrollment and degree completion increase when unemployment rates are high. For Canada, Alessandrini (2014) and King and Sweetman (2002) find results to differ by degree level. The former finds university enrollment to be countercyclical, college enrollment to be pro-cyclical and other non-university post-secondary education to be acyclical, while the latter observe returning to school to be pro-cyclical. In line with most of these findings, our results for Southern Europe also point to countercyclical enrollment and degree completion.

In addition, in many European countries students have some flexibility to adjust their time at university. For instance, Brunello and Winter-Ebmer (2003), in a survey of European countries, and Aina et al. (2011) focusing on students in Italy both find that higher unemployment lengthens time-to-degree, as poor labor market prospects serve as a disincentive to graduate. Such a use of higher education as a “parking lot” is expected to vary by the cost of doing so and to be more likely in the context of low tuition fees [see, e.g., Becker (2006) or Garibaldi et al. (2012)]. For Swiss university students, however, Messer and Wolter (2010) observe that higher unemployment actually shortens time-to-degree by making it harder for students to find part-time jobs, which are commonly used to fund university attendance. This finding is consistent with our results for Scandinavian countries of shorter time-to-degree for those experiencing higher youth unemployment at age 18.

Furthermore, the decision to drop out of higher education might also be affected by macroeconomic conditions. For Italy, Adamopoulou and Tanzi (2017) and Di Pietro (2006) both find dropout rates to be procyclical, consistent with reduced opportunity costs during worse macroeconomic times keeping students in school. In contrast, Bradley and Migali (2019) point to increases in non-completion rates during the Great Recession in the UK. Finally, Blom et al. (2015) show that exposure to higher unemployment rates when young, results in US individuals and in particular women studying college majors with better employment prospects and higher wages, such as STEM fields. While in our data we cannot confirm this finding for Anglo-Saxon countries, we find some of this compensating behavior for men in Southern European countries.

2.2 Institutional context

Our different findings for Anglo-Saxon, Southern European, Western European, and Scandinavian countries show that the impacts of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions depend on context, such as labor markets and education systems. It is therefore useful to briefly consider some of the relevant institutional details for each of these geographies.

The decision to pursue higher education depends both on the costs and the benefits of doing so. Among OECD countries that charge tuition, the average yearly fees for a public institution typically fall between 800 and 1300 USD per year, while in Anglo-Saxon countries fees are over 4500 USD, see OECD (2012) and (2011). However, students in Anglo-Saxon countries also have greater access to substantial financial support in the form of scholarships, grants, or loans resulting in above average university enrollment, see Johnson (2013) and OECD (2011). On the opposite end of the spectrum, tuition in Scandinavian countries is typically free and is paired with generous public subsidies to support non-tuition costs as well. As a result, enrollment in higher education is also quite high. In Southern and Western Europe, tuition rates vary across countries. Some charge no tuition for bachelor degree studies (e.g., Germany and Greece), while others charge yearly fees ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand euros per year [e.g., average tuition for a bachelor’s degree at a public university is roughly 190 euros in France, 1500 euros in Italy and 2000 euros in the Netherlands, see Study in Europe Study in Europe (2021)]. These countries with relatively low tuition but also less developed financial support are characterized by lower levels of enrollment in higher education compared to both Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon countries, see OECD (2012).

Beyond tuition, accommodation and cost of living also matter. In Southern Europe, university students are much more likely to live at home (64–73%) than in either Anglo-Saxon or Western European countries (roughly 20–40%). In Scandinavian countries on the other hand only, 4–10% of university students live with their parents. Not surprisingly, the proportion of students who work while studying is much lower in Southern Europe (25–39%) compared to the other geographies studied in this paper (43–75% across countries) (see Orr et al. 2008; Masevičiūtė et al. 2018).

One can break out the financing of the full costs of attending university, into state (grants and loans), student jobs, and family contributions. While there is quite a range in the proportion of funding provided by family across Anglo-Saxon, Western European, and Southern European countries, family contributions are much lower in Scandinavia. On the other hand, state aid is particularly high (e.g., in Sweden it covers around 69% of costs), and student jobs matter more. As previously noted in Finland, Norway, and Denmark, the share of students who claim that they work to cover living costs and that without their paid job they would not be able to afford their education is well above the European average (see Eurostat 2020; Masevičiūtė et al. 2018).

Finally, returns to higher education are also important. Everything else equal, lower returns might lead to students being more sensitive to changes in the costs of higher education such as those induced by changing macroeconomic conditions. For instance, while the returns to a bachelor’s relative to a high school degree are relatively similar across Western and Southern European countries and a bit higher in Anglo-Saxon countries, they are significantly lower in Scandinavia. Returns to professional or vocational degrees on the other hand tend to be significantly lower than those for a bachelor’s degree in most countries, with the exception of Greece and Germany where these differences are smaller. In Scandinavian countries, characterized by low-income inequality, returns to professional degrees are similar to those for bachelor’s degrees. Lastly, for master’s degrees, returns are higher than either for bachelor’s or professional degrees across all countries studied here (OECD 2019).

3 Data

To test how macroeconomic conditions experienced at age eighteen affect individuals’ decisions regarding post-secondary or tertiary education, we combine PIAAC data on individuals aged 25 to 50 who turned eighteen between 1980 and 2005 with data on youth unemployment and other macroeconomic controls. We consider age 18 to be key for higher education decisions because at that age individuals typically enroll in a vocational or bachelor’s degree program. Even those with intentions to subsequently continue in a master’s or PhD program, typically enroll in a bachelor’s program at this time.

3.1 PIAAC

The PIAAC survey was carried out by the OECD in 2011/2012 in 24 high-income countries and in 2014/2015 in another 9 high-income and middle-income countries. For our analysis, we focus on a subset of eighteen countries which we group into the following four geographies: Anglo-Saxon countries (Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, UK, US,) Southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Spain, Turkey), Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands) and Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden).Footnote 5 PIAAC can be described as the adult version of the OECD’s better-known “Programme for the International Assessment of Students” (PISA). While PISA assesses students’ cognitive skills, PIAAC does so for a country’s population aged 16–65. Apart from cognitive as well as non-cognitive ability scores, PIAAC provides information about individuals’ schooling, continuous education, labor market variables as well as some limited information on parental background.

Given that our analysis focuses on the impacts of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions, we limit our sample to high school graduates, eliminating high school dropouts, for whom there is no higher education decision to be made. We also exclude individuals who migrated to their current country of residence after age eighteen, given that they experienced different macroeconomic conditions at age eighteen. Finally, we limit our sample to those older than 25 because we want to ensure that individuals are old enough to have finished higher education. Individuals in our sample are hence between 25 and 50 years old (25–53 in countries from the second PIAAC wave).

For our study, we focus on the following key variables: First, we have information on individuals’ highest educational degree (ISCED: 0 to 6) as well as their age at graduation.Footnote 6 PIAAC also provides information on uncompleted education and the age at which individuals dropped out of a higher education program. Furthermore, the survey also asks individuals for the area of study, emphasis or major of their highest level of qualification.

We construct our outcome variables in the following way. First, we construct three indicator variables for educational attainment: obtaining any post-secondary or tertiary degree, obtaining a bachelor’s degree or higher, and obtaining a master’s degree or higher. The indicator for graduating with at least a post-secondary degree is recorded as 1 for a person having a vocational, bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate degree. As our sample is limited to high school graduates, the indicator takes on value 0 for individuals who have a high school degree recorded as their highest level of education. On the other hand, our indicator for bachelor’s degree or higher includes those with a bachelor’s, master’s or doctorate degree relative to those with only a high school or a lower post-secondary degree. When defining our indicator for holding a master’s degree or higher, we have to exclude the UK from our sample of Anglo-Saxon countries because PIAAC data for the UK do not differentiate between individuals with a bachelor’s or master’s degree.

For enrollment, we define an indicator variable that takes on value 1 for those whose highest education is recorded as any post-secondary or tertiary degree, as they clearly would have enrolled, but we also include individuals with a high school degree who report to have attempted any type of higher education but who have not completed it. Together, this set of individuals comprises the group that at some point enrolled in higher education compared to high school graduates who never did. Degree non-completion or dropout is defined as a dummy variable that takes on value 1 for individuals who have attempted any higher degrees but have not finished them. This results in a combined measure of non-completion at all levels, from attempted but not completed vocational, bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate degrees. The variable therefore does not indicate whether individuals have ever obtained any post-secondary or tertiary degree at all, nor whether they dropped out of a more or less advanced program compared to their highest level of education.Footnote 7 Note that the variable does not pick up high-school dropouts, as our sample is entirely comprised of high school graduates.

We also analyze the effect of macroeconomic conditions at age eighteen on area of specialization and time-to-degree.Footnote 8 For area of specialization, we focus on so-called STEM fields. We define our dependent variable such that individuals who report to have acquired a specialization in their highest level of education in the following two fields: “science, mathematics, and computing” or “engineering, manufacturing and construction,” are assigned a value of 1, while everybody else is assigned value 0. Regarding the outcome variable “time-to-degree,” PIAAC does not provide this information, but we know at what age individuals finished their highest degree. Assuming that most individuals start post-secondary or tertiary degrees at age eighteen, we hence proxy time-to-degree by taking the difference between age at graduation and age 18. While we refer to this measure as time-to-degree, it strictly measures time-to-degree from the “normal” starting time, at age eighteen. The variable therefore picks up any non-conventional timing track, including those who started at age eighteen and took longer than most to finish, and—observationally equivalent—those who took the normal amount of time to complete their highest degree but for some reason delayed starting their higher education. Note that for the USA, Germany, Austria, Canada, and New Zealand age at graduation is only available in 5-year intervals, and we hence proxy time-to-degree by randomly assigning individuals to years of graduation within each interval.

3.2 Macroeconomic conditions

As our main variable for macroeconomic conditions, we use the national youth unemployment rate from the OECD or the World Bank, which we assign to each individual for the year they turned eighteen. As an example, individuals of age 30 in our sample are assigned values for youth unemployment for the year 2000 (or 2003 for countries from the second wave). We construct two additional macroeconomic controls for the year that individuals turn eighteen. First, to capture differences and changes in labor market institutions we use the percentage of workers who are trade union members among the total number of workers in the economy from the OECD.Footnote 9 Second, we include data from the World Bank on government expenditure to GDP to reflect changes in public employment opportunities. Some higher education decisions like completion of a bachelor’s degree or dropping out are typically made some years after enrollment. Hence, to control for macroeconomic conditions at a later point in time we also include the national unemployment rate which we assign to each individual the year they turned 25. This lag of seven years corresponds with the average time to drop out in our data across all degree levels.Footnote 10 Data on national unemployment also come from the OECD, the World Bank, or the St. Louis Federal Reserve in the case of New Zealand. For most countries in our sample, the data series starts in 1980. However, due to data limitations on youth unemployment rates, for Greece our series starts in 1981, for Austria in 1982, for Belgium, Denmark, and the UK in 1983, for New Zealand in 1986, and for Turkey in 1988.

To provide an idea of the macroeconomic conditions used in our identification, Figs. 3 and 4 in “Appendix” overlay the youth unemployment rate (at age 18) with the evolution of the total unemployment rate measured 7 years later (at age 25) for each country. With very few exceptions, youth unemployment tends to always be higher than national unemployment. One can also see that there is variation both across and within countries regarding periods of lower (booms) and higher youth unemployment (recessions). Also note that given our sample restriction of individuals age 25 or older, our data on macroeconomic conditions observed when individuals are 18 years old end in 2005 (or 2008 for countries in the second wave), and hence, our sample does not include the Great Recession. While youth unemployment and total unemployment tend to move together, this is much less the case when considering a time difference of seven years. Depending on the country, we see that for some, when youth unemployment at age 18 was low, total unemployment at age 25 was relatively high.

3.3 Sample

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for our four samples. The samples include 21,780 individuals in Anglo-Saxon countries, 7106 in Southern Europe, 13,195 in Western Europe, and 8058 individuals in Scandinavian countries. Note that all our observations are weighted using personal weights supplied by PIAAC that have been adjusted such that individual weights are not influenced by a country’s population size. Table 11 in “Appendix” shows the weight of each country in each of the samples. Countries are fairly equally represented. However, two factors explain some of the differences. First, as previously mentioned, some data series start later. For instance, for Turkey we have data staring only in 1988 which explains in part why Turkey has the lowest weight among Southern European countries. But in addition, in Turkey there is a smaller proportion of the population with at least a high school degree and hence among those surveyed in PIAAC fewer end up in our sample.Footnote 11

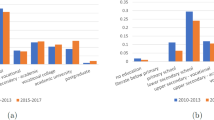

Between 26% (Western Europe) and 38% (Anglo-Saxon countries) of individuals in our samples obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher, with 10–17% even obtaining at least a master’s degree. Between 47–69% obtained some post-secondary degree, including vocational degrees. Among those who completed a high school degree, 57–79% were ever enrolled in some form of post-secondary education (vocational, bachelor’s, master’s or PhD programs). However, 10–17% of individuals in our sample dropped out before obtaining an attempted degree. Around 14–20% specialized in STEM fields. On average and starting at age 18, individuals take between 3 to 5 years to finish their highest degree, including zero time for those who only obtained a high school degree.

Considering macroeconomic conditions, youth unemployment rates experienced at age 18 are lowest in Western Europe and Scandinavia at around 12%, somewhat higher in Anglo-Saxon countries at 14% and much higher in Southern Europe with 27%. While rates are on average much lower at 6–12%, this ranking is similar when considering total unemployment measured at age 25. As expected, union membership as well as government spending is highest in Scandinavian countries, followed by Western Europe, Anglo-Saxon countries, and Southern Europe.

Regarding individual characteristics, between 48–51% of individuals are male. Around 4% of individuals in Scandinavian and Southern European countries are foreign born compared to 9% in Western Europe and 19% in Anglo-Saxon countries. The shares of individuals whose parents have tertiary education are highest in Scandinavia and Anglo-Saxon countries (35–36%), slightly lower in Western Europe (29%) and lowest in Southern Europe (15%). As a proxy for individuals’ socioeconomic status, PIAAC provides information on the number of books that individuals recall to have had in the household when they were children.

For non-cognitive skills, we use “readiness to learn” categories which are intended to capture both motivation and learning strategies. For cognitive skills, we use proficiency levels in numeracy as defined by PIAAC. It is worth noting that both cognitive and non-cognitive skills are measured in 2012 (or 2015 in case of countries from the second wave). However, we expect both measures to be relatively stable over time, and therefore, we treat them as non-time-varying controls that are relevant to past educational choices. We make this assumption in part because cognitive skill categories are quite broad, and hence, even with potential for improvements along the continuous measures due to higher education, we do not expect large changes across these categories beyond high school completion. Similarly, the non-cognitive skill measure of “readiness to learn” may evolve at young ages, but is likely to be fairly set after high school completion. The questions that go into the construction of this index bear some similarity to the Openness category of the Big Five personality traits, which are commonly treated as relatively stable and latent. Ample evidence shows that non-cognitive skills of this type can predict educational and labor market outcomes beyond what is measured by cognitive skills (Almlund et al. 2011).

4 Methodology

To estimate the effects of macroeconomic conditions on individuals’ higher education decisions, we run variants of the following regression

where \(y_{i,j,d_18,y_18}\) indicates the higher education decision (enrollment, dropping out, completion, specialization, or time-to-degree) of individual i in country j who was of age 18 in decade \(d_{18}\) and year \(y_{18}\). Our main coefficient of interest is \(\beta _1\) on the variable \(YU(y_{18,j})\), the national youth unemployment rate at age 18. We also include \(U(y_{25,j})\), the national unemployment rate at age 25. The coefficient \(\beta _2\) hence informs how later macroeconomic conditions impact any continued updating of choices.

In our regression, we also control for individual characteristics \(X_i\), including gender, migrant status, parental background as well as cognitive and non-cognitive ability measures. \(Z(y_{18,j})\) includes other macroeconomic variables such as the share of union members among workers and government spending relative to GDP, measured when individuals were 18 years old. Finally, we also control for decade fixed effects \(D(d_{18}),\) and country dummies \(D_j\). \(\epsilon _{i,j,d_{18}}\) is the residual which we cluster at the country-year-age-18 level. With the exception of time-to-degree, all other outcome variables—enrollment, dropping out, graduating, and specialization choice—are binary variables, and hence, we estimate linear probability models such that values of estimated coefficients indicate the probability that the particular outcome occurs, everything else equal.

Considering our data—a PIAAC cross-section of working-age adults that has been merged with outside data—we obtain our identifying variation from the different years in which individuals turned 18. We then compare similar individuals, some of whom happen to turn 18 during times of high youth unemployment (economic downturns) and others who turned 18 during better macroeconomic times. Given a natural educational path through high school determined largely by age, this “treatment” can be considered exogenous. Hence, conditional on our other controls, \(\beta _1\), provides the causal impact of macroeconomic conditions on various higher education decisions.

One concern when using various measures of macroeconomic conditions in the same regression (youth unemployment, national unemployment measured seven years later, government spending, and share of union members) could be multicollinearity. Table 12 in “Appendix” shows the variance inflation factors for the four variables for all countries in our sample. Most are below 4 and none is larger than 8, indicating that multicollinearity among the four measures is not an important concern.

5 Results

5.1 Graduating with a post-secondary or tertiary degree

Table 2 displays the results for the effects of macroeconomic conditions on graduating with at least a bachelor’s degree. Regarding our main coefficient of interest, for Anglo-Saxon, Western European, and Scandinavian countries, individuals who experienced high youth unemployment at age 18 are less likely to graduate with at least a bachelor’s degree compared to individuals of similar characteristics who experienced lower youth unemployment. For Southern Europe, we find the opposite. Higher youth unemployment experienced at age 18 leads to an increase in the probability to graduate with at least a bachelor’s degree. Regarding macroeconomic conditions measured at a later point in time, for Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian countries we also estimate a negative relationship of graduating with at least a bachelor’s degree with the national unemployment rate measured at age 25.

In terms of magnitudes, a one-percentage-point increase in the youth unemployment rate at age 18 leads to a 0.6%, 0.5%, and 0.4% decrease in the probability of obtaining at least a bachelor’s degree in Scandinavian, Anglo-Saxon, and Western European countries, respectively. Taking into account standard deviations of 4-6% in youth unemployment for these geographies, implies reductions of between 2–3.6% in the probability of obtaining a bachelor’s degree for a one-standard-deviation increase in youth unemployment. On the other hand, in Southern Europe a one-percentage-point (one standard deviation) increase in the youth unemployment rate at age 18 leads to a 0.3% (2.2%) increase in the probability of obtaining at least a bachelor’s degree.

With respect to individual characteristics, results are as expected. Across all four geographies, male students are less likely to graduate with at least a bachelor’s degree, while individuals whose parents have secondary or tertiary education are more likely to graduate compared to those whose parents have lower educational attainment. Coefficients on indicator variables for the number of books at home when growing up indicate that those from more advantageous family backgrounds are more likely to graduate with at least a bachelor’s degree. Higher non-cognitive ability and a higher proficiency in numeracy are also associated with a higher probability to graduate. Finally, regarding other macroeconomic controls, in Scandinavian countries higher government spending and higher union concentration at age 18 are related to a higher probability of graduating from university.

We check the robustness of our results along three dimensions. First, even though our four variables for macroeconomic conditions passed multicollinearity tests, we observe that in many countries government spending correlates closely with youth unemployment.Footnote 12 We hence re-run our estimations excluding this control (see panel A of Table 13). Results for the effect of youth unemployment at age 18 are robust though somewhat weaker, while the effects of national unemployment at age 25 disappear. Second, given significant increases in educational attainment over the time period considered (1980–2005), there might be a concern that our estimates could be driven by the coincidence of increased educational attainment along with falling or increasing youth unemployment.Footnote 13 To address this concern, we re-run our estimations including time trends of up to order four, see panel A of Table 14. Our main results on the effects of youth unemployment at age 18 hardly change but again the effects of national unemployment at age 25 disappear. Finally, one might be worried that in our Southern European sample, results could be driven by Turkey which, different from all other high-income countries in our sample, is classified as an upper middle-income country by the World Bank. We hence repeat our estimations for Southern Europe excluding Turkey. Results in column (1) of Table 15 show that coefficients for the outcome of graduating with at least a bachelor’s degree remain of the same sign and similar magnitude but due to the smaller sample size significance is lost.

As previously discussed, less favorable macroeconomic conditions could induce individuals to pursue higher education or could deter them from it, depending on the mechanisms at play. Given different labor market contexts and education systems across countries, the workings of such mechanisms could differ. For instance, in countries like Germany post-secondary non-tertiary degrees are more important compared to countries like Spain. In the USA, obtaining a post-secondary degree at a community college is a more accessible option for higher education compared to a bachelor’s degree. If in some countries lower post-secondary degrees provide a better alternative during more challenging macroeconomic times, then we might observe an increase in individuals graduating from these degrees rather than from bachelor’s degrees. Furthermore, master’s degrees have had a much longer tradition in Anglo-Saxon countries compared to most European countries, and hence , to “wait out recessions” pursuing a master’s degree might be more common in Anglo-Saxon countries. To check whether we observe such movements toward other degrees for those experiencing high youth unemployment at age 18, we run our regression for the following outcome variables: (i) graduating with any post-secondary degree or (ii) completing a master’s degree or higher.

Table 3 displays the results for the effect of macroeconomic conditions on graduating with any post-secondary degree. We find evidence in support of the hypothesis stated before. In Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries, while we observed higher youth unemployment experienced at age 18 to result in lower bachelor’s degree attainment, we find no significant effects for obtaining any post-secondary degree. For Southern Europe and Scandinavian countries, on the other hand our estimated impacts on degree attainment are nearly unchanged by the addition of professional degrees to the outcome variable.Footnote 14

Table 4 displays the results for the effects of youth unemployment at age 18 on the probability to graduate with at least a master’s degree. Results are similar to the ones for bachelor’ degree completion. In particular, higher youth unemployment rates at age 18 lead to a lower probability of obtaining at least a master’s degree in Scandinavian, Western European, and Anglo-Saxon countries and a higher probability of doing so in Southern European countries. Again we test for the robustness of our results excluding government spending, including time trends and excluding Turkey from our sample of Southern European countries. Panels B and C of Tables 13 and 14 show the results for the first two robustness checks. Estimates for Anglo-Saxon, Western, and Southern European countries are all robust. However, estimates for Scandinavian countries, although similar in magnitude, lose significance when time trends are included. Columns (2) and (3) of Table 15 show that our coefficients for Southern Europe for graduating with at least a master’s degree or from any post-secondary program do not change when excluding Turkey.

Taken together, for Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries, higher youth unemployment at age 18 leads to lower bachelor’s or master’s degrees completion rates, but has no effect when professional degrees are included. This could be due to shifts across degrees within higher education or due to differential enrollment or dropout rates. For Southern European and Scandinavian countries, while youth unemployment at age 18 has opposite effects for degree attainment, estimates are nearly unchanged regardless of whether we consider graduating from any post-secondary, bachelor’s, or master’s degree as our outcome variable. This suggests shifts in or out of higher education (i.e., changes in enrollment or non-completion) rather than shifts across degrees.

To better understand what might be driving these different results across geographies, we estimate how macroeconomic conditions at age eighteen affect enrollment and degree non-completion.

5.2 Enrollment and non-completion

Table 5 displays the results for the effects of macroeconomic conditions on enrollment in any post-secondary program. In Southern Europe, when youth unemployment at age 18 is high, individuals are more likely to enroll in post-secondary programs, while in Scandinavian countries they are less likely. For Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries, we find no significant effects of youth unemployment at age 18 on post-secondary enrollment nor on non-completion rates (see Table 6). The latter also holds for Scandinavian countries. For Southern Europe, on the other hand we see that higher youth unemployment at age 18 leads to higher dropout rates. Our results are robust to excluding government spending as a control variable (see panels D and E of Table 13). However, when including time trends, the negative effect of youth unemployment at age 18 on enrollment for Scandinavian countries loses significance (see panels D and E of Table 14). When excluding Turkey from our sample of Southern European countries, results continue to be the same but regarding non-completion of any post-secondary program, the coefficient of youth unemployment loses significance (see columns (4) and (5) of Table 15).

Given that we do not find any effects on enrollment or dropout rates for Anglo-Saxon or Western European countries, the negative effect of youth unemployment at age 18 on bachelor’s and master’s degree attainment must hence be due to shifts across degrees within higher education. This is confirmed when we re-run our estimations for the limited sample of those ever enrolled in higher education, see panels A to C of Table 7. For Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries, the estimates remain negative and significant for completion of a bachelor’s or master’s degree. Estimates for any post-secondary degree remain insignificant for Western Europe, while they become positive and significant for Anglo-Saxon countries. Under financial constraints during economic downturns, while the same number of students enroll in and complete higher education in Anglo-Saxon countries, a higher proportion seems to opt for a professional rather than a more expensive bachelor’s degree.Footnote 15 We also find supportive evidence when looking at the correlation across cohorts between youth unemployment at age 18 and the share of professional degrees over bachelor degrees or higher among individuals enrolled in higher education. Considering all countries in our sample, this correlation is relatively low (0.13), while for Anglo-Saxon countries it is 0.72, 0.61, 0.32, 0.2, and 0.07 in Ireland, the UK, the USA, Canada, and New Zealand, respectively.Footnote 16

Similar to the case for Anglo-Saxon countries, the evidence previously discussed for Western Europe points toward students shifting between degree levels rather than movements on the extensive margin of higher education. In addition, in Table 5 we see a significant positive impact of the unemployment rate at age 25 on enrollment, which could imply that for Western Europe there may also be a movement across timing of degrees, such as returning to school after having worked.

For Southern Europe, we observe a positive enrollment response in higher education with an increase in dropout rates as a reaction to higher youth unemployment at age 18. However, the first effect seems to dominate, given that we also estimate higher completion rates across all degree levels.

Lastly, for Scandinavian countries we observe how worse macroeconomic conditions at age 18 decrease enrollment in higher education and reduce overall levels of degree attainment, without any effect on non-completion. This suggests that the primary effect of poor macroeconomic conditions operates through a drop in enrollment. We check this conjecture by considering our regressions conditional on enrollment (see Table 7). We still observe lower bachelor’s and master’s degree attainment but no significant effect for professional degrees. In addition, while we saw no overall impact on dropout rates related to youth unemployment at age 18, we find an increase in dropout rates when conditioning on enrollment. In Scandinavian countries, for individuals experiencing higher youth unemployment at age 18, lower enrollment appears to be the key driver behind lower professional degree attainment while a combination of lower enrollment and higher dropout rates are behind lower bachelor’s and master’s degree attainment. This stands in contrast to the case for Southern Europe, where higher post-secondary degree attainment and degree non-completion are direct artifacts of increased enrollment.

Thus far, we have explored the extensive margins of higher education decisions (enrollment, degree completion, and dropout behavior). However, there are other intensive margins that students can use to adapt to unfavorable macroeconomic conditions, for instance specialization choice and time-to-degree.

5.3 Specialization choice and time-to-degree

If as suggested by Blom et al. (2015) macroeconomic conditions alter individuals’ specialization choices and then changes in these decisions could also in part be driving our results. To test whether this is the case we estimate the effect of macroeconomic conditions on completing a degree in a STEM field. Table 8 displays the results. For Southern Europe, we find a positive and significant effect of youth unemployment at age 18 on STEM specializations, consistent with compensating behavior intended to signal student quality during economic downturns. On the other hand, we find a negative effect of unemployment at age 25 for Anglo-Saxon countries. If STEM degrees are typically longer, this result could be driven by individuals switching their specialization later during their studies when faced with continued poor economics prospects. Our results are robust to excluding government spending as a control variable (see panel F of Table 13), and the result for Southern Europe is also robust to the exclusion of Turkey (see column (6) of Table 15).

As mentioned before, students have varying degrees of flexibility in adjusting their time spent in higher education. A changing pool of students entering higher education (as in Southern Europe or Scandinavian countries) or a changing distribution of students across higher education programs (as in Anglo-Saxon or Western European countries) during economic downturns could hence also affect average time to finish one’s highest degree. Changing fields of study could also have an effect.

Table 9 displays the results for the impact of macroeconomic conditions on time-to-degree. For Western Europe, we observe longer time-to-degree for individuals experiencing higher unemployment at age 25. This could reflect a “parking” effect, where students wait out worse macroeconomic times in higher education, or it could reflect a non-standard path for those who enroll later. On the other hand, for Scandinavian countries, we estimate shorter time-to-degree both for those experiencing higher youth unemployment rates at age 18 and those experiencing higher unemployment at age 25.Footnote 17 Hence, Scandinavian students do not seem to be using “parking” as a strategy during difficult macroeconomic times. Recall that while Scandinavian countries generally have no tuition costs for higher education, individuals are more likely to live independently and receive relatively little financial support from family and hence are often more dependent on having a job as a student to afford being able to attend university. As previously mentioned, this result is consistent with the literature for Swiss university students, for whom recessions make it harder to find part-time jobs, commonly used to fund university attendance, thereby shortening time-to-degree (Messer and Wolter 2010).

Again we check the robustness of our results. When excluding government spending as a control variable, effects for Scandinavian countries are robust while we observe a positive effect of youth unemployment at age 18 on time-to-degree for Western Europe instead of unemployment at age 25 (see panel G of Table 13). Results for Southern Europe do not change when excluding Turkey (see column (7) of Table 15).Footnote 18 Finally, we also check the robustness of our results excluding those countries where time-to-degree might be measured poorly, given that age at graduation is only available in five-year intervals (USA, Canada, New Zealand, Germany, and Austria). Our results remain robust, see Table 16.

5.4 Heterogeneity

To further explore our findings, we test for heterogeneity by gender and parental background. Previous literature finds differential effects for men and women when analyzing the impact of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions. Our results for heterogeneity by gender are displayed in Table 17 in “Appendix”.

For Anglo-Saxon countries, for many outcomes we estimate no gender differences regarding the impact of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions. However, the negative effects of youth unemployment at age 18 on the completion of at least a master’s degree and the negative effects of unemployment at age 25 on the completion of at least a bachelor’s degree and on completing a degree in a STEM field seem to be driven primarily by women.Footnote 19 Women in Anglo-Saxon countries hence seem to make additional adjustments in their higher education decisions in response to macroeconomic conditions. For Western Europe on the contrary, the negative effect of youth unemployment at age 18 on the completion of at least a bachelor’s degree seems to be driven primarily by men. We also find the negative effects of higher youth unemployment on the completion of any post-secondary degree as well as on completing a STEM degree to be significant for men only. However, women seem to be the ones waiting out recessions in higher education as we only estimate positive and significant effects for them of higher unemployment at age 25 or age 18, respectively, on enrollment and on time-to-degree.

In Southern Europe, most effects of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions are primarily driven by women, in particular the positive effects on enrollment and dropout behavior, but also on graduating with any post-secondary degree, or graduating with at least a bachelor’s degree. On the other hand, the higher probability of graduating with a STEM specialization when having experienced higher youth unemployment at age 18 is driven by men mainly.Footnote 20 Finally, for Scandinavian countries we find no clear gender differences in the impacts of macroeconomic conditions at age 18 on higher education decisions.

We also analyze how our results depend on individuals’ parental background. In particular, we differentiate between individuals with parents who have tertiary education and those whose parents have secondary education or lower educational attainment, see Table 18 in “Appendix”.

First, note that the direct impacts of parental background are quite large, with individuals with higher parental education being much more likely to enroll in post-secondary education and to graduate with a degree. Regarding the responsiveness to macroeconomic conditions according to parental education, for Anglo-Saxon countries we see that the drop in bachelor’s and master’s degree completion in response to high youth unemployment at age 18 is driven by those whose parents have lower education. This indicates that the “downgrading” of degree type is primarily due to individuals from less advantageous parental backgrounds. Similarly for Western Europe, we see decreased degree attainment driven by those whose parents do not have tertiary education. On the contrary, it is individuals from more advantageous backgrounds in Western Europe that drive higher completion rates of any post-secondary degree or master’s degrees as well as longer time-to-degree when having experiencing high unemployment at age 25. These individuals are probably in a better position to exhibit “parking” behavior in higher education and to wait out poor macroeconomic prospects.

In Southern Europe, the positive effects of higher youth unemployment at age 18 on enrollment, and completion of STEM degrees as well as on non-completion are mainly driven by individuals with lower parental education. It is worth noting that despite no response to macroeconomic conditions along these metrics, those from more advantageous family backgrounds start with higher baseline levels of enrollment and are also overall more likely to specialize in STEM fields.Footnote 21 Furthermore, in particular those with higher educated parents adjust their time-to-degree in response to macroeconomic conditions both at age 18 and at 25, and they also have a lower probability of obtaining a professional degree when the unemployment rate is high at age 25. Considered jointly with increased completion of bachelor’s and master’s degrees, this likely reflects the ability of those from more advantageous family backgrounds to continue studying a higher level degree and to “wait out the storm.” Finally, for Scandinavian countries we observe overall fewer differences in the impact of macroeconomic conditions on higher education decisions by parental background. The only two exceptions are the negative effect of higher youth unemployment at age 18 on the completion of a master’s degree and the positive effect of unemployment at age 25 on degree non-completion, which are both driven by individuals with lower parental education.

6 Conclusions

Macroeconomic conditions experienced at age 18 influence individuals’ decisions in higher education. Taken together, our findings point to individuals switching to shorter and less expensive professional degrees when faced with high youth unemployment at age 18 in Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries. For Southern Europe where we find higher enrollment, dropout, and degree completion rates among individuals who faced high youth unemployment at age 18, our results highlight the importance of opportunity cost considerations. Maybe surprising at first, for Scandinavian countries where tuition in higher education is generally free, financial constraints seem to play a more important role, as among those experiencing high youth unemployment at age 18 fewer individuals enroll and graduate. However, high rates of students living independently of their parents, low levels of family financial support, dependency on student jobs, and lower relative returns to higher education imply that in the face of worse macroeconomic conditions financial considerations in these countries do matter.

During the last three decades, the net costs of education to students have risen in many countries. Even in Europe, students have witnessed higher tuition fees, with particularly large increases in Anglo-Saxon countries like the UK or USA.Footnote 22 Furthermore, living expenses in major cities have also been on the rise (see, e.g.,Gyourko et al. 2013). We consider that analyzing the joint impact of macroeconomic conditions and changes in net costs on higher education decisions could be an interesting avenue for future research. While samples in PIAAC are not large enough for our results to speak to individual countries, our findings also motivate further in-depth research for different countries that simultaneously considers the many components of higher education decisions and the influence of business cycles, potentially taking into account local economic conditions as well.

Notes

For a summary of related literature broken out by the various higher education decisions studied in this paper, see Table 10.

When considering heterogeneity in findings in the literature, it is unclear to what degree results may also be impacted by the way in which macroeconomic conditions are measured. For example, some studies have relied on national unemployment rates (e.g., Betts and McFarland 1995), while others make use of state-level unemployment (e.g., Kane 1994; Long 2015). Studies looking at multiple countries as we do tend to rely on national unemployment rates (e.g., Ayllon and Nollenberger 2016; Arellano-Bover (2020).

Bound et al. (2010) study trends of decreasing college completion rates for the USA and find that while enrollment has increased, this is not matched in completion rates. One-third of lower completion is driven by lower ability of the marginal student and two-thirds are driven by a combination of tightened university budgets paired with the type of schools that marginal students attend (specifically, less selective universities and community colleges). While the authors do not consider business cycle impacts specifically, the suggested mechanism is consistent with the “downgrading” of higher education degrees which we find for Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries.

While this study is very related to ours as it also uses PIAAC data, results are not directly comparable because different from our study the author does not control for ability in his estimations considers only employed and experienced workers aged 36–59 and focuses on a different sample of 19 countries which includes among others Israel, Chile, Japan, and Korea. He shows that labor market conditions at time of transition from education to work have long-term impacts on skill formation.

We exclude all Eastern European ex-communist countries as well as Cyprus because there are no data available before 1990. Turkey, Greece, and New Zealand are the countries included from the second PIAAC wave where data collection happened in 2014/2015 instead of 2011/2012.

ISCED stands for International Standard Classification of Education designed by the United Nations to be comparable across countries. For details, see http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-standard-classification-of-education.aspx.

For example, an individual can drop out of a post-secondary program either before or after completing their highest degree. He or she could enroll in a professional degree, drop out, and enroll in a bachelor’s degree and complete it, thus being recorded as having achieved a bachelor’s degree and having dropped out of a post-secondary program. Likewise, an individual with a bachelor’s degree who pursues a master’s degree but drops out is also being recorded as having a bachelor’s degree and having dropped out of a post-secondary program.

For these two outcomes, there is no relevant information for those who only obtain a high school degree, and we hence set both variables equal to zero for these individuals for comparability with the other estimates and to avoid endogenous sample selection. However, we then also re-run our estimations conditional on enrollment in a post-secondary program.

While the OECD also publishes specific indicators to capture differences in labor market institutions, we cannot use those as none of them are available from 1980 onward.

While we know the exact timing of dropping out for those who enroll and then drop out, this information is clearly missing for those who never dropped out. We therefore use the average time from age 18 to dropping out measured among those who do dropout to determine a time frame that can be applied to all individuals. Notably, this is roughly 7 years across degree types (recall that dropping out of a program can happen either before or after graduating from one’s highest degree attained). We view this as a logical “later” time period for re-evaluation that could influence dropping out, level of degree obtained, and time-to-degree.

According to data from Barro and Lee (2013), in 2010, 28% of individuals in Turkey age 25 and above had at least a high school degree, compared to more than 45% in Italy, the country with the second-lowest share of high-school graduates in our sample.

Among the countries in our sample, this correlation ranges from 0.89 in France, to -0.3 in Germany with most countries showing correlations between 0.5 and 0.7.

Note that PIAAC data are a representative cross-section in 2012 (or 2015) and thus are not representative for each of these retrospective time periods in our data, which contributes to why there is no clear trend in enrollment or degree completion in our data over time. Furthermore, our sample only includes high school graduates, and hence, while there is an increase in educational attainment of the population this is somewhat muted when considering the population of high school graduates.

Recall that the bachelor’s or higher indicator variable includes those who obtained a bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate degree, while the post-secondary degree indicator variable includes professional, bachelor’s, masters’, or doctorate degrees.

When we run regressions using subsamples split by highest degree obtained, we estimate a negative coefficient for youth unemployment on dropout behavior for those who eventually obtain a bachelor’s degree in both Anglo-Saxon and Western European countries. Given that for these countries we see a reduction in bachelor’s degrees obtained when youth unemployment is high at age 18, this seems to suggest that the “downgrading” from expensive bachelor’s degrees to more affordable professional degrees is done at the time of degree selection, rather than individuals trying out a bachelor’s degree and then dropping out to enroll in a professional program. For Western Europe, we also observe a positive estimate for youth unemployment on degree non-completion for the subsample of those who only ever earn a high school degree, indicating that the average zero effect on dropout may also mask some unsuccessful attempts at higher education during poor economic times.

Additional support is also provided by the negative and significant estimate for the unemployment rate at age 25 on bachelor’s degree attainment (see Table 2). Given that we estimate no impacts on degree non-completion or enrollment in post-secondary education overall, this negative coefficient could reflect that those on the margin of continuing to an expensive bachelor’s degree after a typically more affordable professional degree choose not to in the face of poor macroeconomic conditions. However, this estimate loses significance in various of our robustness checks.

From estimations run on subsamples defined by final degree obtained, we see evidence consistent with reduced time-to-degree being driven by those obtaining a bachelor’s degree or a master’s degree or higher rather than a professional degree. In particular, coefficients for unemployment at age 25 are negative and significant among those obtaining these higher level degrees, consistent with a story of reduced “parking” behavior.

While no average impact is found on time-to-degree for Southern European countries overall, when estimation is repeated on subsamples based on highest degree obtained, we see that the average effect varies across degree type obtained, which likely reflects selection of individuals into each subsample based on economic conditions. Recall that Southern European countries during economic downturns see increased enrollment, dropout, and degree attainment, each potentially altering the potential student composition achieving different degree levels.

Note that the full effects for males are calculated as the linear combinations of the coefficient on unemployment and its interactions with male. They are reported in each table.

Increased enrollment and non-completion on the part of women could indicate a change in the quality of the marginal female student when youth unemployment is high. In line with this, while the average correlation conditional on enrollment in our sample between a cohort’s youth unemployment rate at age 18 and non- cognitive skills is \(-\) 0.03 (\(-\) 0.01) for women (for men), we estimate correlations of \(-\) 0.28 (0.06) for Spain, \(-\) 0.23 (0.006) for Italy, \(-\) 0.11 (\(-\) 0.005) for Greece and 0.19 (0.33) for Turkey.

We check whether shifts in STEM specialization might reflect a story of student selection into enrollment by considering how non-cognitive abilities of individuals from less advantageous family backgrounds who are enrolled in post-secondary programs change with macroeconomic conditions, but we find no pattern.

According to a report by the College Board (2017) in the USA between 1987–1988 and 2017–2018, tuition fees in real terms increased by 125%, 129%, and 213% at public two-year institutions, private non-profit four years institutions, and public four-year institutions, respectively.

References

Adamopoulou E, Tanzi GM (2017) Academic drop-out and the great recession. J Hum Cap 11(1):35–71

Aina C, Baici E, Casalone G (2011) Time to degree: students’ abilities, university characteristics or something else? Evidence from Italy. Educ Econ 19(3):311–325

Alessandrini D (2014) On the cyclicality of schooling decisions: evidence from Canadian data. Working Paper 16-14, Rimini Centre for Economic Analysis

Almlund M, Duckworth AL, Heckman JJ, Kautz TD (2011) Personality psychology and economics. In: Hanushek E, Machin S, Woessman L (eds) Handbook of the economics of education. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Arellano-Bover J (2020) The effect of labor market conditions at entry on workers’ long-term skills. Review of Economics and Statistics 12:1–45

Ayllon S, Nollenberger N (2016) Are recessions good for human capital accumulation. NEGOTIATE Working Paper No. 5.1

Barro RJ, Lee J-W (2013) A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. J Dev Econ 104:184–198

Becker SO (2006) Introducing time-to-educate in a job-search model. Bull Econ Res 58(1):61–72

Bedard K, Herman DA (2008) Who goes to graduate/professional school? The importance of economic fluctuations, undergraduate field, and ability. Econ Educ Rev 27(2):197–210

Betts JR, McFarland LL (1995) Safe port in a storm: the impact of labor market conditions on community college enrollments. J Human Resources 741–765

Blom E, Cadena BC, Keys BJ (2015) Investment over the business cycle: insights from college major choice. IZA Discussion Paper No. 9167

Boffy-Ramirez E, Hansen B, Mansour H (2013) The effect of business cycles on educational attainment. mimeo

Bound J, Lovenheim MF, Sarah T (2010) Why have college completion rates declined? An analysis of changing student preparation and collegiate resource. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2(3):129–57

Bradley S, Migali G (2019) The effects of the 2006 tuition fee reform and the Great Recession on university student dropout behaviour in the UK. J Econ Behav Organ 164:331–356

Brunello G, Winter-Ebmer R (2003) Why do students expect to stay longer in college? Evidence from Europe. Econ Lett 80(2):247–253

Charles KK, Hurst E, Notowidigdo MJ (2015) Housing booms and busts, labor market opportunities, and college attendance. NBER Working Paper No. 21587

Christian MS (2007) Liquidity constraints and the cyclicality of college enrollment in the United States. Oxford Econ Paper 59(1):141–169

Clark D (2011) Do recessions keep students in school? The impact of youth unemployment on enrolment in post-compulsory education in England. Economica 78:523–545

College Board (2017) Trends in college pricing 2017. Trends in Higher Education Series, The College Board

Dellas H, Koubi V (2003) Business cycles and schooling. Eur J Polit Econ 19(4):843–859

Dellas H, Sakellaris P (2003) On the cyclicality of schooling: theory and evidence. Oxf Econ Pap 55(1):148–172

Di Pietro G (2006) Regional labour market conditions and university dropout rates: evidence from Italy. Reg Stud 40(6):617–630

Eurostat (2020) Age of young people leaving their parental household. Eurostat, Statistics Explained

Garibaldi P, Giavazzi F, Ichino A, Rettore E (2012) College cost and time to get a degree: evidence from tuition discontinuities. Rev Econ Stat 94(3):699–711

Gyourko J, Mayer C, Sinai T (2013) Superstar cities. Am Econ J Econ Pol 5(4):167–199

Johnson MT (2013) The impact of business cycle fluctuations on graduate school enrollment. Econ Educ Rev 34:122–134

Kahn LB (2010) The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Econ 17(2):303–316

Kane TJ (1994) College entry by blacks since 1970: the role of college costs, family background, and the returns to education. J Polit Econ 102(5):878–911

King I, Sweetman A (2002) Procyclical skill retooling and equilibrium search. Rev Econ Dyn 5(3):704–717

Long BT (2015) The financial crisis and declining college affordability: how have students and their families responded? In: Brown J, Hoxby C (eds) How the great recession affected higher education. University of Chicago Press, NBER Conference Report

Masevičiūtė K, Šaukeckienė V, Ozolinčiūtė E (2018) Combining studies and paid jobs—Thematic review. UAB “Araneum”

Messer D, Wolter S (2010) Time-to-degree and the business cycle. Educ Econ 18(1):111–123

OECD (2011) Education at a Glance. Chapter B: Financial and human resources invested in education. How much do tertiary students pay and what public subsidies do they receive? Indicator B5. OECD Publishing, Paris, OECD Indicators

OECD (2012) How are countries around the world supporting students in higher education?. Education Indicators in Focus, 2012/02 (February) OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2019) What are the earnings advantages from education? In: Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris

Oreopoulos P, von Wachter T, Heisz A (2012) The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(1):1–29

Orr D, Schnitzer K, Frackmann E (2008) Social and economic conditions of student life in Europe: Synopsis of indicators-Final Report-Eurostudent III 2005–2008. Hannover, Hochschul-Informations-System (HIC)

Oyer P (2006) Initial labor market conditions and long-term outcomes for economists. J Econ Perspect 20(3):143–160

Raaum O, Røed K (2006) Do business cycle conditions at the time of labor market entry affect future employment prospects? Rev Econ Stat 88(2):193–210

Sakellaris P, Spilimbergo A (2000) Business cycles and investment in human capital: international evidence on higher education. In: Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy, Vol. 52 North-Holland, pp 221–256

Schnitzer K, Zempel-Gino M (2002) Social and economic conditions of student life in Europe 2000. Hannover, Hochschul-Informations-System (HIC), 2000

Schnitzer K, Kuster E, Middendorff E (2005) Eurostudent Report 2005-Social and Economic Conditions of Student life in Europe 2005. Hannover, Hochschul-Informations-System (HIC), 2005

Sievertsen HH (2016) Local unemployment and the timing of post-secondary schooling. Econ Educ Rev 50:17–28

Study in Europe (2021) Compare tuition fees. https://www.studyineurope.eu/tuition-fees

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Both authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Both authors acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Grants: ECO2017-82882-R and PID2020-112739GA-I00). Jennifer Graves also acknowledges funding from Comunidad de Madrid and UAM through the “Proyectos I+D para Jóvenes investigadores” (Grant: SI1-PJI-2019-00326). Some of the ideas contained in this paper have been previously included in a publication in 2020 entitled “Impacto de los cíclos económicos sobre las decisiones de los estudiantes de educación superior,” in: monografia sobre educación by Fundación Ramón Areces and Fundación Europea Sociedad y Educación.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and Tables 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Graves, J., Kuehn, Z. Higher education decisions and macroeconomic conditions at age eighteen. SERIEs 13, 171–241 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-021-00252-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-021-00252-6