Abstract

The challenges behind this research were encountered while drilling into the Ilam, Mauddud, Gurpi, and Mishrif Formations, where severe drilling instability-related issues were observed across the weaker formations above the reservoir intervals. In this paper, geomechanical parameters were carried out to determine optimum mud weight windows and safe drilling deviation trajectories using the geomechanical parameters. We propose a workflow to determine the equivalent mud window (EMW) that resulted in 11.18–12.61 ppg which is suitable for Gurpi formation and 9.36–13.13 ppg for Ilam and Mishrif Formations, respectively. To estimate safe drilling trajectories, the Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, and unconfined compressive strength (UCS) parameters were determined. These parameters illustrate an optimum drilling trajectory angle of 45° (Azimuth 277°) for the Ilam to Mauddud Formations and less than 35° for the Gurpi Formation. Our analysis reveals that maximum horizontal stress and Poisson’s ratio have the most impact on determining the optimum drilling mud weight windows and safe drilling deviation trajectories. On the contrary, vertical stress and Young’s modulus have minimum impact on drilling mud weight windows and safe drilling deviation trajectories. This study can be used as a reference for the optimal mud weight window to overcome drilling instability issues in future wellbore planning in the study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A question that may come into the readers’ mind is: why does the determination of the geomechanical parameters have the most impact on decreasing risks during wellbore operation, and why this study is focused on the Ilam, Mauddud, Gurpi, and Mishrif formations. The answer is that generally, the breakout happens around the wellbore at the same orientation as the minimum principal stress, with a high-stress concentration. Therefore, the borehole enlargement happens when drilling fluid density is less than the strength of the rocks. Thus, shear failure happens at a low drilling fluid density, while the tangential stress is high. On the other hand, the Ilam, Mauddud, Gurpi, and Mishrif formations consist of argillaceous limestone and marl with scattered asphalt, with the salt aquifer. Therefore, the estimation of the geomechanical parameters is necessary to be determined and implemented to reduce the drilling risks during operation. Another question that may come into the readers’ minds is: what is the novelty of this research? The answer is that the novelty of this research refers to the determination of the mud weight window, optimum drilling trajectory, and wellbore stability, including new observations which lead to new results in the study area.

The geomechanical parameter estimation is often used to prevent lost circulation and the determination of optimum drilling trajectory. To determine the safe mud weight window and the best drilling trajectory, it is required to determine the intervals of tensile rock failure and shear rock failure. The pressure of the drilling mud will cause a tensile failure in the wellbore, and drilling mud will be lost into the formation if the mud weight is applied higher than the safe mud window. Shear failure or breakout will occur while this weight is applied lower than the safe mud window (Le and Rasouli 2012; Zhang 2013; Zoback et al. 2003). Tensile rock failure occurs in the upper meters near the surface, while shear rock failure takes place at greater depth, below which, rock failure does not occur. Parameters such as wellbore deviation and principal stress directions play a remarkable role in calculating the mud weight window. Principal stresses directions are important to be quantified for petroleum field development (Radwan 2021a). Geomechanical modeling, wellbore stability analysis, and associated parameters have been examined in many research in recent years. Radwan et al. investigated pore pressure and fracture gradients using a variety of data and methods (Radwan et al. 2019, 2020, 2021). They also carried out reservoir geomechanical modeling in order to analyze in situ stress and its relationship with reservoir properties such as depletion, production, and wellbore stability (Radwan and Sen 2021a, 2021b; Radwan et al. 2021). To improve under-balanced drilling, Abdelghany et al. applied the depth-of-damage method in geomechanical modeling (Abdelghany et al. 2021). Kassem et al. (2021) calculated the geomechanical parameters to investigate the effect of depletion and fluid injection in a sandstone reservoir (Kassem et al. 2021). Shahbazi et al. (2020) investigated the impact of reduced production rates on wellbore stresses by constructing a 2D geomechanical model using log data and drilling information in two Iranian oil fields.

Optimization of mud weight window is the most critical factor to prevent wellbore instability during directional drilling. An optimum mud weight window entails wellbore stability (Li and Zhang 2011) and prevents lost circulation.

Before drilling, the stress on the ground is less than the strength of the rocks and thus the balance of the ground is retained. But both during and after the drilling, part of the rock column is drilled and moved out of the well, and the drilling mud replaces that and puts pressure on the wellbore wall, thus spreading stress around the wellbore, and the balance of stress in the ground is disrupted and the stress generated by the drilling is created. To maintain wellbore stability and regulate these stresses, the well must be drilled with the appropriate mud weight (Darvishpour et al. 2019). Failure to pay attention to this issue causes wellbore instability and problems such as collapse, kick, wash-out, or tighten, increasing drilling costs, stopping production, and eventually might indeed cause well loss (Das and Chatterjee 2017).

To determine wellbore stresses, the rock strength must be known, an appropriate model must be selected, and an appropriate rock failure criterion should be chosen. Rock strength is an essential parameter in wellbore stability because it shows the behavior of the rock when it is under in situ stress conditions (Radwan 2021a, b, c). The rock strength properties can be obtained from well logs data and empirical equations (Peng et al., 2001; Rahimi 2014).

Heller and Zoback (2014) provided 28 relationships by different researchers for estimating the unconfined compressive strength (sandstones or carbonate rocks and shale). In most of these relationships, the main variables are transit time of sonic waves, ultrasonic wave velocity, Young’s modulus, and porosity.

In situ stresses, which are carried out in various methods, have been published by Radwan et al. (2021a, b, and c). The International Society of Rock Mechanics suggests “hydraulic fracturing” as the most reliable approach to determine in situ stress. This technology can increase the production of a well, and the proper use of this method can improve reservoir permeability and consequently improve the production of the wells (Gao et al. 2019a, b, c; Kassem et al. 2021; Radwan et al. 2021d).

In this research, we carried out an optimum mud weight estimation using geomechanical parameters in two steps. Consequently, we propose a drilling deviation survey based on the geomechanical models.

Geological setting

The study area is located in the Persian Gulf. The Persian Gulf Basin is considered the richest region in the world in terms of hydrocarbon resources (Ghazban 2007). The studied reservoir in this oil field is referred to as Sarvak Formation.

The Mesozoic stratigraphy of the Persian Gulf basin is characterized by episodic development of intra-shelf basins over the northeastern margin of the Arabian plate (Sharland et al. 2001; Van Buchem et al. 2011). During Aptian and Cenomanian, these basins resulted in deposition of organic-rich sediments which adjoined porous rim carbonates on their margins (Vahrenkamp et al. 2015). The Cenomanian intra-shelf basin was developed following the deposition of the lower parts of the Sarvak Formation, which are regionally continuous and dominated by carbonates (Razin et al. 2010). These carbonates are overlain in the west and east by shallow-marine carbonates of the Mishrif platform rimming an NE-SW trending intra-shelf basin in the central parts of the study area (Vahrenkamp et al. 2015). Recent seismic studies in the Iranian sectors of the prolific Persian Gulf region (OEOC 2014) have resulted in numerous oil and gas discoveries within the Cretaceous Series. The Middle Sarvak Formation (Cenomanian) is considered to be an important source rock within the Cretaceous petroleum system of the eastern Persian Gulf basin (Alipour 2017; Hosseiny et al. 2016). This source rock is suggested to charge the overlying Mishrif and Ilam carbonates in some oilfields of the study area (Alipour et al. 2017; Alizadeh et al. 2017; Hosseiny et al. 2017).

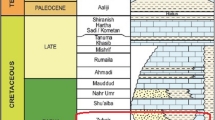

Sarvak formation is part of the Bangestan Group, containing a neritic carbonate consisting of limestone and dolomite, and this formation has shallow and deep facies. The lower part of the Sarvak Formation consists of limestone and pelagic rock. The upper part includes massive limestone containing algae, echinoderms, and rudists (James and Wynd 1965; Ghazban 2007). The Sarvak Formation is derived from Tange Savrak in the mount Bnatsegnan (northwest of Behbahan City) in Khuzestan Province (James and Wynd 1965; Rahimi and Riahi 2020). The Sarvak Formation in stratigraphical terms is equivalent to Khatiyah, Mauddud, Ahmadi, and Mishrif Formations in this area (Ghazban 2007). The Upper Sarvak Formation is equivalent to the Mishrif Formation deposited in the south part of the Persian Gulf. This formation is regarded as a significant hydrocarbon reservoir of this area (Van Buchem et al. 1996; Rahimi and Riahi 2020). The lower part of Mishrif is Khatiyah Formation that consists of organic matter-rich mudstone and wackestone. The Mauddud Formation with Albian–Cenomanian age consists of a shallow-water carbonate with widespread distribution in the Persian Gulf. The Mauddud Formation is a carbonate-dominated succession that emerged from transgression after the Nahr Umr Formation-related clastic-dominated sediments in the Persian Gulf (James and Wynd 1965) Fig. 1.

Cretaceous stratigraphy chart of the Persian Gulf (Rahimi and Riahi 2020)

Petrophysical properties

Petrophysical parameters such as effective and total porosity, water saturation, shale volume, and volume of minerals in this reservoir were calculated using probabilistic analysis. But first, the mineralogy composition was determined. Three lithology cross-plots for the Ilam, Mauddud, Mishrif, and Khatiyah formations, based on neutron vs. density and sonic vs. Vp/Vs logs, were performed. The average shale volume calculated for the studied formations is about 2.6%, which indicates that these formations are composed mostly of limestone and calcite. Since the velocity of sonic waves varies according to the material and lithology of the formation, shale, limestone, and dolomite are easily distinguishable. According to the available sonic log, the lithology of the studied formations is made of calcite and limestone with a few amount of shale.

In the next step, neutron density logs are used as a basis for depth matching of other logs, like compensated gamma ray (CGR), thermal neutron (CNL/TNPHI) porosity, compressional slowness (DTCO), photoelectric factor (PeF), and resistivity from the wellbores (HE-E1 and HE-E2). These logs were employed to perform the petrophysical model. The petrophysical evaluation results (Fig. 2) suggest a carbonate reservoir with limited shale volume (2.6%) and a porosity average of 10%. Figure 2 shows the volume of water saturation in the second track and the volume of minerals in the third track, both from the right side.

In tracks 1 and 2, the amount of water saturation and porosity is observed from the right, respectively. At the depth of 3750 m, low porosity is evident in the shaly interval and an increase in water saturation is observed. In tracks 6 and 7 from the right, according to the PEF log, the presence of limestone can be seen throughout the depths interval of the wellbore. The PeF log shows a value of about 5, representing the presence of limestone but decreases at a depth of 3750 m. The decrement of the PeF value proves the existence of the inter-shaly layer. On the other hand, the electrical resistivity log value increases at a depth of 3750 m. The density and neutron logs (tracks 6 and 7) decrease at a depth of 3750 m, representing the shaly interval. The conventional well logs that were employed in the petrophysical model were displayed in the other column of Fig. 2. It is worth mentioning that the shale volume was calculated using a corrected gamma-ray log (SGR).

Materials and methods

Wireline logs consisting of compressional density, gamma ray, resistivity, FMI log (rose diagram), petrophysical evaluation results, and pore pressure points from MDT tools are the available data in this analysis. Based on the log data coverage in the entire well as well as the availability of direct downhole measurements, we have carefully chosen one well, namely HE-E2 for the geomechanical analysis presented here. Drilling and well reports were studied and used in this work. Applied methods are discussed below.

Wellbore stresses and pore pressure (pp)

Usually, in situ stress is divided into three parts: vertical stress, minimum horizontal stress, and maximum horizontal stress. The formation rocks are in front of the field stresses before drilling, but after drilling these rocks are pushed out in the cutting form and the wellbore must withstand the stresses of the field. These stresses relate to the wellbore trajectory as well as the impact of the field dominant stress on the well-drilling location (Nelson et al. 2006).

Maximum and minimum horizontal stresses

The minimum and maximum horizontal stresses are two of the three major stresses required for each geomechanical study (wellbore stability analysis, sand production, and hydraulic fracture) (Shmin and Shmax). Estimation of horizontal stresses is one of the main steps in geomechanical modeling and contributes to an assessment of the accuracy of the measured geomechanical model (Gholilou et al. 2017). The stresses applied to the rocks underground are almost identical in various directions under isotropic conditions and before well drilling (SV = Shmin = Shmax). However, these values change after drilling and these changes are more noticeable on a significant regional scale in active tectonic areas such as anticlines, fault-adjacent areas, salt domes, and other active tectonic areas. Mechanical failures in the wellbore are induced by adjusting the horizontal stress values. These mechanical failures can be in the maximum horizontal stress direction in the form of tensile failures or breakdown, and shear failures or breakouts are in the minimum horizontal stress direction which both are produced roughly parallel to the wellbore axial. Using acoustic and density logs, as well as reservoir properties like Poisson’s ratio, vertical stress, and pore pressure, the stress profile in the reservoir is determined (Almalikee and Al-Najim 2018). There are many methods to assess the direction and location of these stresses. Image logs are one of the most detailed methods to classify the features of these stresses. Figure 3 shows the location and direction of breakouts created by shear stress observed on the rose diagram.

The minimum horizontal stress (Shmin) can be determined directly from the minifrac test, hydraulic fracture, or LOT/XLOT test; however, the maximum horizontal stress (Shmax) cannot be computed directly. Even though both of them can be calculated using indirect methods with acceptable accuracy. The poroelastic stress equation is used in conventional ways to estimate the minimum horizontal stress gradient as a function of vertical depth. The theory of poroelasticity, which explains how a lithified, porous medium-like rock deforms when the pore space is filled with fluid and pressurized, describes the fluctuation of Sh as a function of. Pp (Kumpel 1991). One of the most often used approaches in the industry for determining horizontal stresses under isotropic conditions is the poroelastic method. Changes in elastic stiffness characteristics caused by structural anisotropy are used to predict the minimum and maximum horizontal stresses in this method (Abdelghany et al. 2021; Maleki et al. 2014). As a result, one of the conventional methods for indirectly determining the minimum and maximum horizontal stresses is to employ the poroelastic method (Blanton and Olson 1997) (Eqs. 1, 2):

where \(\upupsilon \) is the Poisson’s ratio, α is Biot coefficient, PP is the pore pressure, E is the static Young’s modulus, and \(\varepsilon \) is the tectonic strain in the x and y directions (Aghajanpour et al. 2017).

Model prediction and calibration with wellbore data (observed breakouts on FMI or caliper logs) were used to identify these tectonic strains. Biot coefficient or effective stress coefficient (α) can be calculated using various parameters such as bulk modulus (Biot 1941), porosity (Krief et al. 1990), and permeability (Klimentos 2003). Theoretically, it is in the range of 0–1 (0 ≤ α ≤ 1). This parameter is normally derived from Eq. 3:

where Kb is the volumetric parameter of the rock total volume and Kg is the volumetric parameter of the rock grains. The Biot coefficient was considered 1 in this analysis. If LOT/XLOT is available, the horizontal stresses are adjusted to determine the actual tectonic strain values (Gholami et al. 2015; Zoback 2010).

Fracture analysis using formation micro-imager (FMI)

Analysis of natural fractures such as determining the direction of extension and slope, morphology (open or closed), density, and opening rate of fractures, especially in Iranian carbonate reservoirs, can be the basis of further studies. Fractures are of great importance in the exploration, development of hydrocarbon fields, and hydraulic failure.

The raw data of the FMI logs are processed, analyzed, and interpreted to identify the types of fractures and also to determine the current stress direction in Santoniane carbonates (Ilam Formation) in southwestern Iran. The tectonic trend of the fractures was determined in the wells, and the results are presented as a rose diagram of slope and the extension of discontinuities:

Figure 3 shows the results obtained from the FMI log, the extension and slope of induced fractures due to drilling operation, and maximum horizontal stress at an angle of 61.2 and 318.2 degrees (right figure). The extension and slope of the breakouts and minimum horizontal stress are in the direction of 134.5 and 44.4 degrees (left figure).

Vertical stress

The pressure exerted by combining the vertical column pressure of various rock layers and the fluids inside themselves at a certain depth is overburden stress, commonly called vertical stress (Almalikee and Al-Najim 2018). Overburden pressure at each point in the subsurface is due to the weight of upper layers and the role of different factors, such as rock type, porosity type, rock density, and the density of fluid filling the pores, diagenetic impact, tectonic factors, etc. This pressure includes lithostatic and hydrostatic pressures. Lithostatic pressure is the weight of the rock column, and hydrostatic pressure is the weight of the fluid column filling the pore spaces. These pressures are a function of the specific gravity of the rocks and fluids within the pores and increase in proportion to the depth. The sum of these two pressures refers to overburden stress. In a homogeneous property, vertical stress can be easily determined from Eq. 4:

But in most situations, to measure the vertical stress, the initial intervals of the drilled well do not have the density information. Consequently, a density can be calculated using a linear equation at the initial intervals from the ground to the target depth (Rana and Chandrashekhar 2015):

where ρEX is the estimated density, ag is the distance drilling floor to ground level, tvd is the true vertical depth, ρML is the surface density which is about 2 (g/cm3), and a and a0 are the calibration parameters in this equation (Eq. 5). The hydrostatic pressure is also determined using Eq. 6, which is the pressure at the depth of the fluid column (Bjørlykke et al. 2015):

where ρf is the fluid density (gm/cm3). As a consequence, with increasing depth, the pressure gradient increases. For the analyzed interval, the amount of overburden stress was measured and the vertical stress gradients at the top and bottom of the formations are presented in Table 1.

One of the vertical stress parameter applications is to use it to estimate the pore pressure. There are two ways to measure pore pressure. The first technique is direct pore pressure measurement using special logging tools such as MDT and RFT. Pore fluid trapped in the formation porosities greatly affects the in situ stress magnitudes. Abnormal formation pressure yields increased complexity in drilling and nonproductive times. Direct downhole measurements provide the best PP estimates; however, these data are usually recorded only in the reservoir intervals (Sen et al., 2019, 2020; Agbasi et al. 2021; Radwan 2021b).

The second approach utilizes the indirect measurement of pore pressure from well log data such as density, resistivity, and acoustic. But experimental equations that use well logs can be used in non-reservoir periods, such as Eaton’s equation (Eaton 1975). Modular Formation Dynamic Tester (MDT) tools information has been made available in this analysis at reservoir intervals. The pore pressure gradient was obtained from MDT pore pressure points in this reservoir.

Sonic log (DT) is sensitive to pressure changes because there is a relationship between porosity, compression, pore pressure, and sonic parameters. An increase in the depth interval of the wellbore increases compaction and in turn decreases porosity. Therefore, the bulk modulus and shear modulus increase and the compressibility decreases. By variation of these parameters, the contact surface of the grains will increase, and as a result, the velocity of the sonic wave will increase. But in the high-pressure zone, the compaction rate will decrease (Fig. 4).

Many of the failure criteria have been proposed: Mohr–Coulomb (Coulomb 1973), Mogi–Coulomb (Mogi1971), Hoek–Brown (Brown and Hoek 1980), and single-parameter parabolic failure criteria (Li et al. 2005). It should be noted that the most common cases in the normal breakout and breakdown stress regime are Sθ > Sz > Sr and Sr > Sz > Sθ (Al-Ajmi 2012; Gholami et al. 2014). Several researchers have identified some problems related to the estimated values of rock strength or lack of adequate knowledge of stress levels in the estimated stress values for failure criteria (Song and Haimson 1997; Vernik and Zoback 1992). The Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion is one of the failure criteria that is commonly used in the oil industry due to better efficiency in terms of time and its linear consistency (Gholami et al. 2017, 2014, 2015). Of course, by ignoring the impact of intermediate stress and using the minimum and maximum stress values, this failure criterion is used only to measure the maximum mud pressure for wellbore stability. This criterion’s mathematical relationship focused on the main stresses is as follows (Mohr 1900) (Eqs. 7, 8):

The Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion’s linearity is presented as follows (Tan et al. 2019):

where S1 and S3 are the main maximum and minimum stresses and SC is the unconfined compressive strength (Eq. 9). Equation 10 describes the relationship between normal and shear stress when two adhesion coefficients and internal friction angle factors are used in this criterion:

where τ is the shear stress, \(\mathrm{\varphi }\) is the internal friction angle, Sn is the normal stress, and C is the adhesion coefficient. Table 2 presents the calculation of mechanical failure stresses (breakout and breakdown) using the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion in various modes of induced stresses.

Two internal friction angles and adhesion coefficient are significant parameters defined by the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. It is used to determine these two parameters in the laboratory through three-axis testing on drilling core samples. But there are also empirical relationships in which it is possible to quantify these parameters. The following equations are provided to quantify these two parameters:

where \(\mathrm{\varphi }\) is the internal friction angle, NPHI is the neutron porosity, Vshale is the shale volume (usually calculated from the gamma-ray log), UCS is the uniaxial stress, and C represents the adhesion coefficient (Eqs. 11,12).

In the shale segment, the internal friction angle and Young’s coefficient are decreasing; on the contrary, these related subjects increase in thick limestone segments such as Ilam and Mishrif. Also, the Poisson’s ratio in all formations decreases relatively with an increase in shale volume (Table3).

Figure 5 shows the results of dynamic parameters, which include the following from left to right, respectively:

The first track includes logs of drill bit size (BS), well diameter (CAL), and amount of radioactivity (SGR) which are considered in agreement with dynamic parameters. The second track represents Young’s modulus, which is lower in the shaly interval than in the limestone interval. The third and fourth tracks show the Poisson’s ratio and rigidity, which increases as a bulk modulus in track five in limestone and decreases in shaly formations. The sixth and seventh tracks, which include the compressional shear wave velocity and the Poisson ratio, respectively, show a good agreement with lithology as well as other dynamic parameters.

The obtained results of UCS, the Poisson’s ratios, the Young coefficient, and the safe drilling deviation angle are shown in Table 4. These results in the reservoir segment all comprise Ilam and Mauddud formations with more than 150 MPa unconfined compressive strength (UCS). The Poisson’s ratio is less than 0.25 psi, and the Young’s coefficient is between 80 and 64 GPa. Considering the calculated results, the optimum wellbore deviation angle for the reservoir segment is more than 45° (277° azimuth). These calculations for shale and flysch Gurpi segments are variable, so the amount of UCS has a range of changes from 30 to 150 MPa, Poisson’s ratio from 0.25 psi to 0.3 psi, and Young’s coefficient included some changes from 32 to 64GPa.

The calculated issues in different Gurpi formation segments and safe drilling trajectories indicated 30° to 45° deviation.

In Table 5, formations depth and their intervals are provided with lithology type.

The effect of wellbore’s azimuth and diversion on mud weight window and safe mud weight window estimation

To calculate the geomechanical parameters, raw data and information of drilling wells in the Ilam, Mauddud, Mishrif and Khatiyah formations are collected. Petrophysical and geomechanical evaluation of the mentioned formations is investigated and performed (Fig. 6). Figure 6 illustrates the acoustic, density, shear, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio logs.

In Fig. 6, the first track from the left represents the density log, which shows the lithological changes with respect to depth. In the second and third tracks, the sonic logs show the changes in sonic slowness at different depths, which increase with decreasing density and vice versa. The fourth track is Young’s modulus, which increases in magnitude and velocity with increasing density which shows a smaller value in clay content, and its low value indicates a decrease in the amount of bulk and shear modulus. The fifth track shows the Poisson’s ratio increasing in carbonate formations compared to shaly formations, which indicate more stability in the carbonate formations.

To calculate the dynamic and static geomechanical parameters, it is necessary to calculate the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) and the equivalent mud weight (EMW) which is the mud weight needed to balance formation fluid pressure. In Figs. 7 and 8, Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio window are used to calculate the UCS and EMW. In this section, shale volume log is also used to validate these calculations.

In Figs. 7 and 8, the first track from the left, a gamma-ray log is displayed, which shows the shale volume. In the second track, the UCS log shows that the uniaxial compressive strength has drastic changes in the studied formations and that the highest compressive strength is observed in limestone and calcite thick layers. In this track, both static and dynamic values are depicted side by side, which validates the results obtained from the dynamic log. In the third and fourth tracks, Young’s modulus and the equivalent mud weight (EMW) logs are shown. These logs indicate that the drilling mud weight increases in areas of shale where Young’s modulus decreases. Also, the calculated drilling mud weight indicates that in the intervals where the amount of uniaxial compressive strength decreases, the amount of mud weight increases to increase wellbore stability (Fig. 7).

Estimation of mud weight window

Optimum mud weight estimation comprises an allowable range of drilling mud weight. Mechanical earth modeling (MEM) analyzes wellbore stability based on failure criteria. Failure criterion is a mathematical equation that models the behavior of a rock at the moment of failure. Coulomb (1776) introduced the simplest yet most important failure criterion. According to this criterion, rock failure will occur when shear stress in a plane overcomes the force of friction and rock cohesion in that plane. According to Mohr’s theory, friction in a plane is opposite to the direction of motion, and its value is directly proportional to the tension that compresses the two planes. Therefore, this criterion can be written as follows (Colmenares and Zoback 2002):

\({\sigma }_{n}\) influences perpendicular to the fracture plane and plays a positive role in rock stability. In the above equation, \(\tau \) is the coefficient of internal friction and C is the cohesion (Eq. 13). The main disadvantage of the MC criterion is to ignore the effect of intermediate stress. In this failure criterion, the intermediate stress does not affect the normal and shear stresses. Moreover, it is assumed that intermediate stress does not affect the occurrence of rock failure. MC failure criterion can be expressed by maximum (\(\sigma \) 1) and minimum (\(\sigma \) 3) principal stresses. The maximum and minimum principal stresses can be easily calculated from Mohr’s circle (Gholami et al. 2014):

In the above equations, \(\uptheta \) is the angle between normal to the plane and maximum principal stress direction (Eq. 14, 15).

In the above equation, \(\varphi \) (angle of internal friction) is the refraction angle that can theoretically change from 0 \(^\circ \) to 90 \(^\circ \). However, the practical range of changes in this angle is smaller and ranges from 0 \(^\circ \) to 30 \(^\circ \), so, according to the above equation, it is obvious that X can vary between 45 \(^\circ \) and 90 \(^\circ \) (Eq. 16).

Figure 9 specifies the low level of drilling mud weight in black color. If the weight of drilling fluid reaches lower than the black line, borehole collapse pressure would occur and might bring up wellbore collapse in shale formations and make the diameter bigger or smaller. In the lower level of the least mud weight, the shear failure can occur, called collapse pressure.

Tensile failure occurs in the upper meters near the surface, while shear failure takes place at greater depth, below which, failure does not occur. The tensile failure region shown in red color is related to the failure pressure of the formation or high drilling mud weight level. It implies that if the weight of drilling fluid inside the wellbore is more than the red line, it might bring up a tensile failure. It increases the probability of entrance of drilling fluid to the formations, namely lost circulation.

A higher amount leads to the tensile failure range called fracture pressure (Gao et al. 2019a, b, c). Shearing strength is often defined by the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion and two parameters: failure envelope cohesion and internal friction angle.

Regarding the results, whatever observed in Gurpi formation shows a distinct value in the weight of drilling fluid and other geophysical parameters such as maximum horizontal stress, formation pore pressure (Gao et al., 2019a; Radwan 2021; Baouche et al. 2021), the safe mud window range between minimum horizontal stress and minimum mud weight for wellbore collapse, shear failure, and tensile failure. Consequently, these changes indicate the shale segment in the depth of 3800 m. Therefore, to preserve wellbore stability, it is vital to increment the weight of drilling fluid. In the Ilam and Khatiyah formations, the weight of the drilling fluid window is increased, whereas some changes occurred in other parameters, which are presented below: Albeit the weight of drilling fluid in the reservoir area in the Ilam is decreased, the maximum horizontal stress is increased. In this area, the formation pressure indicates changes in the shear failure region from the least level of mud weight to the least level of formation fluid pressure.

In Khatiyah formation, the maximum horizontal stress is decreased. By contrast, the high level of mud weight increases, reducing the tensile failure boundary (Fig. 9).

Figures 10, 11, and 12 depict safe zones in terms of mud weight and drilling direction, indicating certain stable and unstable depths along the investigated well. The blue color in Stereonets denotes the safe locations for drilling orientation without any breakout or breakdown (stable orientation), whereas the red color denotes the unstable orientation. The mud weight employed at that depth is shown by the point marked on these figs. The optimal deviation, azimuth, and mud weight are provided to prevent shear and tensile failures. Figures 10, 11, and 12 are the typical polar plots in STABview. The geomechanical analysis indicates that the direction of minimum horizontal stress (σh) and maximum horizontal stress) σH (in Gurpi is NW–SE and NE–SW. Drilling more than 50° deviations in Gurpi formation might bring up various problems such as wellbore breakdown. Therefore, the safe mud weight window in Gurpi formation is from 11.18 to 12.61 ppg, with 35° drilling inclination and 277° azimuth (Fig. 10). It should be noted that 1 pound per gallon (ppg) is equivalent to 7.48 pounds per cubic foot (pcf).

The direction of minimum horizontal stress (σh) and maximum horizontal stress (σH) in the Mishrif and Ilam formations is NE–SW and NW–SE, respectively. Drilling more than 60° inclination in the Mishrif and Ilam formations might bring up different problems such as wellbore breakout. Therefore, the equivalent mud weight window for the Ilam and Mishrif formations is 9.36 to 13.13 ppg, with 45° drilling inclination and 277° azimuth.

Discussion

The geomechanical modeling approach presented here is used to provide a more appropriate representation of a stable mud weight window by applying a geomechanical analysis incorporated with UCS, the Poisson’s ratios, and Young’s modulus. Haider Qasim et al. 2017 worked on wellbore instability problems. They conducted that a variety of factors play a significant role in controlling the instability hassles and in determining an optimum mud weight to avoid sticking and borehole collapse pressure, which might bring up wellbore collapse in shale formations and make the diameter bigger or smaller.

Haider Qasim et al. (2017) determined the in situ stress and induced stresses using numerous field and laboratory data from the study area. It is carried out by analyzing wellbore failure, core analyses, and field tests such as the triaxial test and minifrac which are vital to improving geomechanical modeling (Abdelghany et al. 2021). In contrast, in this study, no core samples nor the core data were available to be used; therefore, using a compressional wave velocity log, reservoir geomechanical parameters are calculated. The sonic log measures shear wave and compressional wave velocities with medium density.

Moreover, with a proper format in Techlog, we yielded dynamic parameter estimations such as the Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, bulk modulus, and other geomechanical parameters of the numerical data process.

Bagheriet al. (2021) used conventional well logs, DSI log, FMI log, petrophysical evaluation results (mineral and porosity), and pore pressure points from MDT tools. In this work, we have compared our data with Bagheri et al. (2021) to figure out how our findings in one of the Iranian hydrocarbon reservoirs are far or similar. From our point of review, in Sarvak formation, we have simply divided geomechanical properties based on three different formations (Ilam, Sarvak, Gurpi), and to get the values for each formation, we extracted them to six categories (Gurpi Flysch, Gurpi shale, Ilam, Mishrif, Khatiyah, Mauddud) and then divided the result by 6 to define the boundaries of the proposed six formations. As far as the reservoir section consists of Ilam and Sarvak formations, we subtracted them to one section to calculate UCS and Phi. The Middle Sarvak Formation (Cenomanian) is believed to be an important source rock within the Cretaceous petroleum system of the eastern Persian Gulf basin (Alipour 2017; Hosseiny et al. 2016), and as far as Baghery et al. (2021) worked on the same reservoir system (Middle Cretaceous (Albian–Thoronian)), we carried out our findings that are similar to them, whereas, by using a simple approach, we separated different formations to make it more sensible. Equivalent mud weight values in Gurpi formation range from 11.18 to 12.61 ppg and in Ilam and Mishrif formations (reservoir section) fluctuated from 9.36 to 13.13 ppg. Similarly, Baghery et al. (2021) concluded that the equivalent mud weight for the reservoir section is from 10 to 16.8 ppg.

Sensitivity analysis determines how different values of an independent variable affect a particular dependent variable under a given set of assumptions. In other words, sensitivity analyses study how various sources of uncertainty in a mathematical model contribute to the model’s overall uncertainty. Tornado charts are commonly used for sensitivity analysis, by facilitating the comparison of the effects of one variable (or uncertainty) on the output (value) of an independent variable. Sensitivity analysis is performed using tornado plot. Sensitivity analysis reveals the sensitivity of the model to the input parameter variations. The tornado plot is pivotal to understanding some parameters that need to be more accurately counted as practical and useful parameters placed in the plot. Some parameters with maximum variations are placed at the top of the chart. On the contrary, the parameters with minimum variations are placed lower (Fig. 13). The most useful parameter on equivalent mud weight is the maximum horizontal stress gradient. On the other hand, the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio are the least important (Fig. 13).

Concluding remarks

It was found that the wellbore trajectory and drilling fluid density in operation have a significant impact on the wellbore stability in the study area. Core measurements are very important to deliver reliable results, whereas, in our study, no core samples nor the core data were available to be used. Yet, we have used other datasets utilizing well log data, drilling, and geological data to create a wellbore stability model applicable in the study area. The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) value in the reservoir zone, including Ilam to Mauddud formations, shows that the safe inclination angle is more than 45° (277° azimuth); alternatively, drilling more than 60° might bring up different problems such as collapse, kick, increasing drilling costs, and stopping production and eventually might indeed cause well loss. Consequently, the safe inclination angle for Gurpi formation is 35°, and drilling more than 50° might bring up various problems such as wellbore breakout, wash-out, or tightening.

Geomechanical analysis based on geomechanical parameters illustrates that the direction of minimum horizontal stress and maximum horizontal stress in Gurpi formation is NW–SE and NE–SW, and for Mishrif and Ilam formations is NE-SW and NW–SE, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis shows that the most significant parameter in the mud weight window is maximum horizontal stress; by contrast, Poisson’s ratios and Young’s modulus are the least important.

Abbreviations

- E :

-

Young’s modulus, GPa (Mpsi)

- G :

-

Shear modulus, GPa (Mpsi)

- K :

-

Bulk modulus, GPa (Mpsi)

- S Hmax :

-

Maximum horizontal stress, MPa (psi)

- S hmin :

-

Minimum horizontal stress, MPa (psi)

- V p :

-

Compressional wave velocity, m/sec (ft/sec)

- μ :

-

Shear modulus

- λ :

-

Lame’s coefficient

- V s :

-

Shear wave velocity, m/sec (ft/sec)

- ΔP :

-

Difference between wellbore pressure and pore pressure, MPa (psi)

- ρ :

-

Bulk density, g/cm3 (kg/m3)

- ρ w :

-

Water density, g/cm3 (kg/m3)

- σ :

-

Stress, MPa (psi)

- σ 1 :

-

Maximum principle stress, MPa (psi)

- σ 2 :

-

Intermediate principle stress, MPa (psi)

- σ 3 :

-

Minimum principle stress, MPa (psi)

- σ r :

-

Radial stress at the wellbore, MPa (psi)

- σ y :

-

Stress in y-axis in Cartesian coordinate system, MPa (psi)

- σ z :

-

Axial stress at the wellbore, MPa (psi)

- σ zz :

-

Stress in z-axis in Cartesian coordinate system, MPa (psi)

- \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{zz}}\) ε zz :

-

Axial tensile strain εxx

- \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{\alpha \alpha }}\) :

-

Bulk strain

- \({\sigma }_{0}\) :

-

Or ΔP is the hydrostatic stress

- \(v\) :

-

Poisson’s ratio, dimensionless;

- \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{c}}\) :

-

Uniaxial rock strength

- \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{t}}\) :

-

Tangential stress, MPa;

- \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{h}}\) :

-

Minimum horizontal stress, MPa;

- \(\alpha \) :

-

Biot coefficient;

- \(V\) :

-

Poisson’s coefficient

- \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{V}}\) :

-

Total (volumetric) mean stress

- \({P}_{\mathrm{f}}\) :

-

Drilling fluid pressure

- E :

-

Elasticity modulus (Gpa)

- \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{H}}\) :

-

Tectonic strains in maximum horizontal stresses

- \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{h}}\) :

-

Tectonic strains in minimum horizontal stresses

- \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{H}}\) :

-

Maximum horizontal stress, MPa;

- E :

-

Elasticity modulus

- ε ax :

-

Strain in axial direction x

- σ x :

-

Axial strain in axial direction x

- υ :

-

Poisson's coefficient

- σ θ ’ :

-

Hoop stress alteration due to the introduction of osmotic pressure, MPa (psi)

- τ :

-

Shear stress, MPa (psi)

- υ :

-

Poisson’s ratio, unitless

- Ф :

-

Internal friction angle, degrees

- φ :

-

Wellbore azimuth, degrees

- Ø :

-

Formation porosity, fraction

- DTC and DTs:

-

Compressional slowness and shear slowness (sonic log)

- FMI:

-

Formation micro-imager

- DSI:

-

Dipole shear sonic imager

- MDT:

-

Modular formation dynamics tester

- ρ and ρb and RHOB:

-

Density

- D and Z and dz:

-

Depth

- g :

-

Gravity

- tvd:

-

True vertical depth

- Ph:

-

Hydrostatic pressure

- PP:

-

Pore pressure

- Edyn and Esta:

-

Young’s dynamic modulus and Young’s static modulus

- ν dyn and ν sta :

-

Dynamic Poisson’s ratio and static Poisson’s ratio

- UCS:

-

Uniaxial compressive strength

- α and BIOT:

-

Biot coefficient

- C1 and C2:

-

Caliper 1 and caliper 2

- LOT/XLOT:

-

Lake off test and extended leak off test

- ε :

-

Tectonic strain

- FIT:

-

Formation integrity test

- Sθ and Sz and Sr:

-

Tangential stress and axial stress and radial stress

- C :

-

Adhesion coefficient

- φ :

-

Internal friction angle

- NPHI:

-

Neutron porosity

- Vshale:

-

Shale volume

- CMW_KICK:

-

Kick pressure

- CMW_LOSS:

-

Mud loss

- CMW_MAX_MTS:

-

Breakdown pressure

- CMW_MIN_MC:

-

Shear failure minimum pressure

- MW:

-

Mud weight

- KICK-BREAKOUT:

-

Difference between shear failure and kick

- LOSS-BREAKDOWN:

-

Difference between loss and tensile failure

- AIc:

-

Compressional acoustic impedance

- AIs:

-

Shear impedance

- RCc:

-

Compressional reflection coefficient

- RCs:

-

Shear reflection coefficient

- Sv and Sn:

-

Vertical stress and normal stress

- PHIE:

-

Effective porosity

References

Abdelghany WK, Radwan AE, Elkhawaga MA, Wood D, Sen S, Kassem AA (2021) Geomechanical modeling using the depth-of-damage approach to achieve successful underbalanced drilling in the gulf of suez rift basin. J Petrol Sci Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.108311

Agbasi S, Sen N, Joseph Inyang S, Etuk E (2021) Assessment of pore pressure, wellbore failure and reservoir stability in the Gabo field Niger Delta, Nigeria. Implic Drill Reserv Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2020.104038

Aghajanpour A, Fallahzadeh SH, Khatibi S, Hossain MM, Kadkhodaie A (2017) Full waveform acoustic data as an aid in reducing uncertainty of mud window design in the absence of leak-off test. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 45:786–796

Al-Ajmi AM (2012) Mechanical stability of horizontal wellbore implementing Mogi-coulomb law. Adv Pet Explor Dev 4(2):28–36

Al-Ajmi AM, Zimmerman RW (2006) Stability analysis of vertical boreholes using the Mogi-Coulomb failure criterion. Int J Rock Mech Mining Sci 43(8):1200–1211

Alipour, Alizadeh B, Chehrazi A (2017) A thermal maturity analysis of the effective cretaceous petroleum system in the southern persian gulf basin may 2017 oil & gas science and technology, Revue de l IFP doi: https://doi.org/10.22050/IJOGST.2017.53898

Alizadeh M, Alipour A, Chehrazi (2017) Chemometric classification and geochemistry of oils in the Iranian sector of the southern Persian Gulf Basin. Org Geochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.05.006

Almalikee HSA, Al-Najim FMS (2018) Overburden stress and pore pressure prediction for the North Rumaila oilfield. Iraq Model Earth Syst Environ 4(3):1181–1188

Bagheri H, Tanha AA, Doulati Ardejani F, Heydari-Tajareh M, Larki E (2021) Geomechanical model and wellbore stability analysis utilizing acoustic impedance and reflection coefficient in a carbonate reservoir. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 11:3935–3961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-021-01291-2

Baouche R, Sen S, Chaouchi R, Ganguli SS (2021) Modeling in-situ tectonic stress state and maximum horizontal stress azimuth in the Central Algerian Sahara - a geomechanical study from EL Agreb, EL Gassi and Hassi Messaoud fields. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 88:103831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2021.103831

Biot MA (1941) General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J Appl Phys 12(2):155–164

Bjørlykke K, Høeg K, Mondol NH (2015) Introduction to Geomechanics: stress and strain in sedimentary basins. Petroleum geoscience. Springer, Berlin, pp 301–318

Blanton T, Olson JE (1997) Stress magnitudes from logs: effects of tectonic strains and temperature. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition. Society of petroleum engineers

Brown E, Hoek E (1980) Underground excavations in rock. CRC Press, London

Colmenares and Zoback (2002) A statistical evaluation of intact rock failure criteria constrained by polyaxial test data for five different rocks. Int J Rock Mech Mining Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(02)00048-5

Coulomb CA (1973) Essai sur une application des regles de maximis et minimis a quelques problemes de statique relatifs a l'architecture (essay on maximums and minimums of rules to some static problems relating to architecture)

Darvishpour A, Seifabad MC, Wood DA, Ghorbani H (2019) wellbore stability analysis to determine the safe mud weight window for sandstone layers. Pet Explor Dev 46(5):1031–1038

Das B, Chatterjee R (2017) Wellbore stability analysis and prediction of minimum mud weight for few wells in Krishna-Godavari Basin, India. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 93:30–37

Eaton BA (1975) The equation for geopressure prediction from well logs. In: Fall meeting of the society of petroleum engineers of AIME. Society of petroleum engineers

Gao Q, Cheng Y, Han S, Yan C, Jiang L (2019) Numerical modeling of hydraulic fracture propagation behaviors influenced by pre-existing injection and production wells. J Pet Sci Eng 172:976–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.09.005

Gao Q, Han S, Cheng Y, Yan C, Sun Y, Han Z (2019) Effects of non-uniform pore pressure field on hydraulic fracture propagation behaviors. Eng Fracture Mech. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.106682

Gao Q, Cheng Y, Han S, Yan C, Jiang L, Han Z, Zhang J (2019) Exploration of non-planar hydraulic fracture propagation behaviors influenced by pre-existing fractured and unfractured wells. Eng Fracture Mech. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.04.037

Ghazban F (2007) Petroleum geology of the Persian Gulf, Tehran University and National Iranian Oil Company press

Gholami R, Moradzadeh A, Rasouli V, Hanachi J (2014) Practical application of failure criteria in determining safe mud weight windows in drilling operations. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng 6(1):13–25

Gholami R, Rasouli V, Aadnoy B, Mohammadi R (2015) Application of in situ stress estimation methods in wellbore stability analysis under isotropic and anisotropic conditions. J Geophys Eng 12(4):657–673

Gholami R, Aadnoy B, Foon LY, Elochukwu H (2017) A methodology for wellbore stability analysis in anisotropic formations: a case study from the Canning Basin, Western Australia. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 37:341–360

Gholilou P, Behnoudfar S, Vialle M, Madadi, (2017) Determination of safe mud window considering time-dependent variations of temperature and pore pressure analytical and numerical approaches. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2017.02.002

Heller R, Zoback M (2014) Adsorption of methane and carbon dioxide on gas shale and pure mineral samples. J Unconv Oil Gas Resour 8:14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juogr.2014.06.001

Hosseiny A, Rabbani Reza, Seyed A, Moallemi, (2016) Source rock characterization of the Cretaceous Sarvak Formation in the eastern part of the Iranian sector of Persian Gulf. Org Geochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.06.005

James GA, Wynd JG (1965) Stratigraphic nomenclature of Iranian Oil Consortium Agreement Area Am. Assoc Petrol Geol Bull 49:2182–2245

Kassem AA, Sen S, Radwan AE, Abdelghany WK, Abioui M (2021) Effect of depletion and fluid injection in the mesozoic and paleozoic sandstone reservoirs of the october oil field central gulf of suez basin implications on drilling production and reservoir stability. Nat Resource Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-021-09830-8

Klimentos T (2003) NMR applications in petroleum related rock mechanics: sand control, hydraulic fracturing, wellbore stability. In: SPWLA 44th annual logging symposium. OnePetro

Kumpel HJ (1991) Poroelasticity: parameters reviewed. Geophys J Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.1991.tb00813.x

Le K, Rasouli V (2012) Determination of safe mud weight windows for drilling deviated wellbores: a case study in the North Perth Basin. WIT Trans Eng Sci 30(81):83–95

Li C-G, Zheng H, Ge X-R, Wang S-L (2005) Research on two-parameter parabolic Mohr strength criterion and its damage regularity Yanshilixue Yu Gongcheng Xuebao/chin. J RockMech Eng 24(24):4428–4433

Li S and Zhang J (2011) Wellbore stability modeling and real-time surveillance for deepwater drilling to weak bedding planes and depleted reservoirs. SPE/IADC 139708 presented at the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference and Exhibition held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Maleki S et al (2014) Comparison of different failure criteria in prediction of safe mud weigh window in drilling practice. Earth Sci Rev 136:36–58

Mogi K (1971) Fracture and flow of rocks under high triaxial compression. J Geophys Res 76(5):1255–1269

Mohr O (1900) Welche umstande bedingen die elastizitatsgrenze und den bruch eines materials. Z Ver Dtsch Ing 46(1524–1530):1572–1577

Nelson E, Hillis R, Mildren S (2006) Stress partitioning and wellbore failure in the West Tuna Area. Gippsland Basin Explor Geophys 37(3):215–222

OEOC (2014) PC2000 Marine seismic operation. http:// www. oeoc. ir/marine-operations. html. Accessed on 2014.

Peng S, Wang X, Xiao J, Wang L, Du M (2001) Seismic detection of rockmass damage and failure zone in tunnel. J China Univ Min Tech 30(1):23–26 ((in Chinese))

Radwan AE (2021) Modeling pore pressure and fracture pressure using integrated well logging, drilling based interpretations and reservoir data in the Giant El Morgan oil Field, Gulf of Suez Egypt. J African Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2021.104165

Radwan A, Sen S (2020) Stress path analysis for characterization of in situ stress state and effect of reservoir depletion on present-day stress magnitudes: reservoir geomechanical modeling in the Gulf of Suez Rift Basin. Egypt Nat Resource Res 30:463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-020-09731-2

Radwan AE, Sen S (2021) Characterization of in-situ stresses and its implications for production and reservoir stability in the depleted El Morgan hydrocarbon field Gulf of Suez Rift Basin Egypt. J Struct Geol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2019.103743

Radwan A, Abudeif A, Attia M, Mohammed M (2019) Pore and fracture pressure modeling using direct and indirect methods in Badri Field, Gulf of Suez. Egypt J Afr Earth Sci 156:133–143

Radwan AE, Abudeif AM, Attia MM, Elkhawaga MA, Abdelghany WK, Kasem AA (2020) Geopressure evaluation using integrated basin modelling, well-logging and reservoir data analysis in the northern part of the Badri oil field, Gulf of Suez Egypt. J African Earth Sci 162:103743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2019.103743

Radwan AE, Abdelghany WK, Abdelghany WK (2021) Present-day in-situ stresses in Southern Gulf of Suez, Egypt: Insights for stress rotation in an extensional rift basin. J Struct Geol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2021.104334

Rahimi M, Riahi MA (2020) Static reservoir modeling using geostatistics method: a case study of the Sarvak Formation in an offshore oilfield. Carbonates Evaporites 35:62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13146-020-00598-1

Rahimi R (2014) The effect of using different rock failure criteria in wellbore stability analysis, MS Thesis, Missouri University of Science and Technology

Rana R, Chandrashekhar C (2015) Pore pressure prediction a case study in Cambay basin. Geohorizons 20(1):38–47

Razin FT, van Buchem, (2010) Sequence stratigraphy of Cenomanian-Turonian carbonate platform margins (Sarvak Formation) in the High Zagros, SW Iran: An outcrop reference model for the Arabian Plate pril 2010. Geol Soc London Special Pub 329(1):187–218. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP329.9

Sen S, Kundan A, Kalpande V, Kumar M (2019) The present-day state of tectonic stress in the offshore Kutch-Saurashtra Basin, India. Mar Pet Geol 102:751–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.01.018

Sen S, Kundan A, Kumar M (2020) Modeling pore pressure, fracture pressure and collapse pressure gradients in offshore Panna, Western India, implications for drilling and wellbore stability. Nat Resour Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-019-09610-5

Sen S, Ganguli SS (2019) Estimation of pore pressure and fracture gradient in Volve Field, Norwegian North Sea. In SPE oil and gas India conference and exhibition, Mumbai, India, April 9–11. SPE-194578-MS. https://doi.org/10.2118/194578-ms.

Shahbazi K, Zarei AH, Shahbazi A, Tanha AA (2020) Investigation of production depletion rate effect on the near-wellbore stresses in the two Iranian southwest oilfields. Petr Res 5(4):347–361

Sharland R, Brett Davies A, Peter Heward A, Horbury D (2001) Arabian plate sequence stratigraphy. GeoArabia https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279778628

Song I, Haimson BC (1997) Polyaxial strength criteria and their use in estimating in situ stress magnitudes from borehole breakout dimensions. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 34(3–4):116.e1-116.e16

Tan T, Zhang H, Li J, Wang H, Cai Z, Yu Q, Yang M, Chen Y, Liu K, Deng Q, (2019) Analysis on collapse pressure and fracture pressure of a borehole in natural gas hydrate formation. In: The 53rd U.S. Rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, New York City, New York

Vahrenkamp VC, Laer PV, Franco B, and Celentano MA, (2015) IPTC-18470-MS Late jurassic to cretaceous source rock prone intra-shelf basins of the Eastern Arabian Plate – Interplay between tectonism, global anoxic events and carbonate platform dynamics

Van Buchem F, Razin P, Homewood P, Philip J, Eberli G, Platel J, Roger J, Eschard R, Desaubliaux G, Boisseau TM (1996) High-resolution sequence stratigraphy of the Natih Formation (Cenomanian/Turonian) in Northern Oman distribution of source rocks and reservoir facies. GeoArabia. https://doi.org/10.2113/geoarabia010165

Van Buchem MD, Simmons H, Droste R, Davies Brett (2011) Late aptian to turonian stratigraphy of the eastern Arabian plate - depositional sequences and lithostratigraphic nomenclature. Pet Geosci. https://doi.org/10.1144/1354-079310-061

Vernik L, Zoback MD (1992) Estimation of maximum horizontal principal stress magnitude from stress-induced well bore breakouts in the Cajon Pass scientific research borehole. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 97(B4):5109–5119

Zhang J (2013) Borehole stability analysis accounting for anisotropies in drilling to weak bedding planes. Int J Rock Mech Mining Sci 60:160–170

Zoback MD (2010) Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Zoback MD (2010) Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Zoback MD, Barton CA, Brudy M, Castillo D (2003) Determination of stress orientation and magnitude in deep wells. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 40(7/8):1049–1076

Acknowledgements

Thanks are given to anonymous domain experts for their input and insight, without which this research would not have been possible. The second author would like to acknowledge the Research Council of the University of Tehran.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoseinpour, M., Riahi, M.A. Determination of the mud weight window, optimum drilling trajectory, and wellbore stability using geomechanical parameters in one of the Iranian hydrocarbon reservoirs. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 12, 63–82 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-021-01399-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-021-01399-5