Abstract

Experimental work has been conducted to study the influence of gas injection on the phase inversion between oil and water flowing in a vertical pipe. A vertical transparent pipe test section line of 40 mm ID and 50 cm length was used. The test fluids used were synthetic oil and filtered tap water. Measurements were taken for mixture velocity, superficial water velocity, superficial gas velocity, and input superficial oil velocity ranging from 0.4 to 3 m/s, 0.18 to 2 m/s, 0 to 0.9 m/s, and 0 to 1.1 m/s. Most of the experiments were conducted more than two times, and the reproducibility of the experiments was quite good. Special attention was given to the effect of oil and water concentration where phase inversion took place with and without gas injection. The results showed that the phase inversion point was close to water fraction of ~ 30%, for both water friction direction changes (from water to oil or from oil to water) and that the effective viscosity increases once the mixture velocity increases. On the other hand, the results with gas injection showed that gas injection had no effect on the oil or water concentration where phase inversion occurred. Furthermore, the study investigated the effect of gas–oil–water superficial velocity on the total pressure gradient in the vertical pipe. It was found that the total pressure gradient was fast and increased at high superficial gas velocity but was slow at low superficial gas velocity. When the superficial oil velocity increased, the total pressure gradient approached the pressure gradient of an oil–water two-phase flow. The obtained results were compared with few correlations found in the literature, and the comparison showed that the uncertainty of the flow pattern transition peak in this study is very low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nowadays, gas lift optimization is very significant in the petroleum industry. A suitable lift optimization can reduce the operating cost and maximize the oil recovery from the reservoir under different operating conditions. The first stage in the conventional design of a gas lift well is determining the optimum depth of the operating valve, together with finding out the injection point depth, the required injection gas flow rate, and the production liquid flow rate. The gas lift method is normally used during oil production, where the injected gas transfers the fluid to the surface by reducing the fluid load pressure on the reservoir formation by decreasing fluid density. The challenge of accurately predicting pressure drops in either flowing or gas lift wells has increased. Many particular solutions for specific conditions are available but none is generally accepted as a comprehensive solution for any condition. The reason is that the analysis of the two-phase flow is very complex and difficult even for a particular condition due to a large number of variables involved. The difference in velocity and the geometry of the two phases strongly influence pressure drop. Guet et al. (2003) showed that the efficacy of the gas lift increases with decreasing bubble size of the gas injected into the flowing oil well. Currently, because of the water production from an oil well or due to the injection of water into the reservoir for enhancing oil recovery, oil production is often associated with a highly produced water quantity. Consequently, there will be three-phase flow in a vertical pipe once the gas lift method is also applied.

Many gas lift optimization problems have been addressed in different ways in the existing literature. Indeed, many studies related to gas lift process optimization and pressure drop correlations have been conducted and discussed (Khamehchi et al. 2009; Rashidi et al. 2010; Hamedi et al. 2011; Khishvand and Khamehchi 2012). In some other studies, a new function for the gas lift performance curve (GLPC) or new methods for solving the optimization problem have been presented. Mayhill (1974) studied GLPC and analyzed the relation between gas injection rate and oil production rate. Hong (1975) used a cubic spline interpolation method for the estimation of the gas lift performance curves. Camponogara and Nakashima (2006) proposed a solution for the gas lift optimization problem related to constraints on the gas pipelines. Ayatollahi et al. (2004) suggested a typical intermittent gas lift model for pressure-depleted reservoirs where the mean calculation basis of the transient pressure gradient in this model could be formulated and solved mathematically. The study has shown that oil production can be improved by this type of artificial lift. Djikpesse et al. (2010) presented a new method to do such optimization involving non-smooth models. Khamehchi et al. (2009) proposed a nonlinear method for oil field optimization based on gas lift optimization. Gomez (1974) proposed a way to generate a gas lift performance curve and developed a computer program to fit a second-degree polynomial to it, together with a procedure to obtain the optimum gas injection rate. Santos et al. (2001) developed a numerical model to study the behavior of the conventional intermittent gas lift, the intermittent gas lift with a chamber, the intermittent gas lift with the plunger, and the intermittent gas lift with a pig. They ran under various reservoir conditions, at different operation’s limits. The obtained results could be used to find the most adequate intermittent gas lift design for any well. Rodriguez et al. (2003) studied and tested new correlations for pressure drop in core-annular flow in vertical glass pipes (2.84 cm ID) and obtained excellent results which are in agreement with data from the literature. Ho and Li (1994) presented pressure drop measurements in horizontal (15.74 mm ID) and vertical (62 mm ID) pipes using very viscous water-in-oil emulsion as the core and an aqueous solution as the annulus. Bannwart et al. (2004) and Rodriguez et al. (2003) proposed basic correlation for pressure drop in vertical and horizontal core-annular flows, and their results are in very good agreement with data from the literature.

However, not much investigation has been carried out about the effect of gas injection on pressure gradient in an oil–water vertical flow (Descamps et al. 2006, 2007). The experiment of Descamps et al. (2006) was on the three-phase flow in a vertical pipe. Their results have shown that with air injection, the pressure gradient of three-phase flow was all the time smaller than for the case of oil–water flow, but at the point of phase inversion, the pressure gradient might be higher than for oil–water flow. To improve the understanding of the effect of gas injection on the flow of liquids, the present study carried out an experimental investigation of oil, gas, and water flow in a vertical pipe. The focus was on the influence of gas injection on the pressure gradient. The experiments measured the pressure gradient at cases without and with gas injection. The total pressure gradient was measured for different mixture velocities as a function of the water fraction. The obtained results were compared with those measured in the oil and water two-phase flow found in the literature.

Statement of the problem

In typical gas lift well when a liquid or gas flows along a pipe, either naturally or artificially, friction between the pipe wall and the liquid or gas causes pressure or head loss (Fig. 1). This loss affects the production performance of the gas lift wells. Pressure drop and flow rate are dependent on one another. The greater is the pressure drop, the higher will the flow rate be and vice versa. In order to have flow in a pipe system, a pressure difference is needed, as fluids flow from a high-pressure point to a low-pressure point. One can identify three components that define this pressure difference, hydrostatic pressure loss, frictional pressure loss, and kinetic pressure loss.

For most applications, kinetic losses are minimal and can be ignored. Thus, the equation that describes the overall pressure losses can be expressed as the sum of two terms:

The total loss in pressure within the vertical pipe is as follows:

where hydrostatic head equation is:

The Darcy–Weisbach equation (Glenn 2002) is used to determine the frictional loss in pressure within the pipe:

The Blasius (1913) empirical correlation for turbulent pipe friction factors is derived from first principles and extended to non-Newtonian power-law fluids. The friction loss factor, f, is determined from the Blasius equation, utilizing the Reynolds number (Re) and roughness inside the pipe:

For laminar (smooth) flows, it is a consequence of Poiseuille’s law (which stems from an exact classical solution for the fluid flow):

The Reynolds number (Re) is given by:

The principle of gas lift is that the gas injected into the tubing mixes with the produced fluids, decreases the density of the column of fluid in the tubing, and helps to displace the fluid to the surface leading to a lower flowing bottom-hole pressure. Unfortunately, there are barriers to having an efficient gas lift system. When producing fluid, some degree of friction loss and inefficiency is inevitable. Friction loss essentially refers to resistance caused by fluid flowing through pipes and fitting. That resistance results in decreased flow pressure and decreased fluid velocity. Energy loss due to friction is dependent on a variety of factors, such as friction between fluid and piping walls, friction between the fluids (higher viscosity fluids have higher losses), turbulence created when redirecting fluid via a sharp turn in the pipe or a restriction, flow rate (high flow rates translate to high losses), and pipe length (longer pipes and small diameter pipes have higher losses). However, the presence of multiple phases greatly complicates pressure drop calculation.

Therefore, the current conventional gas lift method still needs to be improved to decrease the pressure losses along the tubing where the properties of each fluid present must be taken into account. Also, the interaction between each phase and friction losses due to the interaction of the fluid with the pipe wall must be considered. Mixture properties must be used, and therefore, the gas and liquid in situ volume fractions throughout the pipe need to be determined.

Experiments

Experimental setup

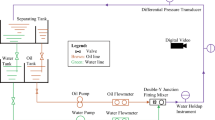

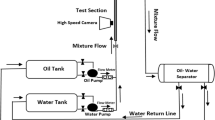

The experiments were performed in the multiphase pilot flow facility shown in the schematic diagram (Fig. 2). The test section was kept vertical during all experiments. The tube has a length of 6 m and 40 mm ID. The pipe material is stainless steel connected by a U-turn. For flow visualization, acrylic test section pipe, 50 cm length and 40 mm ID, is placed at the end of the first 6-m section. After the test section, the mixture gas–oil–water flows from the test section to the multiphase separator where the separated phases are then reverted to their corresponding storage tanks.

The experimental facility was built to simulate the flow environments in a vertical pipe and be able to measure the pressure gradient. The effects of temperature on the oil viscosity were characterized using rheometer. The fluids used in the tests were synthetic oil and filtered tap water having the physical properties shown in Table 1.

The oil and water were pumped at the same time from their storage tanks through two flow meters and were combined at the beginning of the test section through a modified T-junction. The oil system consisted of an oil tank, pump, pipe viscometer, and metering unit. The oil tank volume was approximately 30 bbl. The pipe viscometer section was equipped with temperature transmitters at both ends and differential pressure transducers measuring the pressure drop across the pipe section. The temperature was automatically regulated to 40 °C, within a range of ± 0.3 °C. The oil flow rate was controlled by the automatic control valves located downstream of the mass flow meters. The water process consisted of a water tank, pump, pipe viscometer, metering unit, and oil–water separator. The water was pumped from the water tank through the pipe viscometer into a metering section and then to the mixing point. The water tank volume was also approximately 30 bbl.

Measurement procedure

There were four sets of data. The first set consisted of oil and water data without gas injection at different mixture velocities and different oil and water concentrations. The experiments were focused more on the critical concentration where phase inversion occurs. In the second set, gas injection took place through a nozzle injector, and again, care was given to its impact on the critical concentration and on pressure drop along the pipe. Each measurement point needed 5-min recording at constant flow conditions.

The study was conducted at several mixture velocities as a function of water fraction with and without gas injection. The selected mixture velocity rates of 0.4 m/s, 0.8 m/s, 1 m/s, 2 m/s, 1.6 m/s, and 3 m/s were tested with and without gas injection at different gas volume fractions (GVFs) of 0.52%, 1.04%, 2.05%, 2.56, 3.79, 7.28, and 9.52%. Further investigation was carried out to measure the pressure gradient in the vertical pipe by keeping either the superficial water velocity constant or superficial gas velocity constant and increasing the superficial oil velocity for both cases. Measurements were taken for input superficial water velocity from 0.18 to 2 m/s, input superficial oil velocity from 0 to 1.1 m/s and input superficial gas velocity from 0 to 0.9 m/s. Most of the experiments were conducted more than two times, and the reproducibility of the experiments was quite good.

Results and discussion

Oil–water flows without gas injection

The first aim of the study was to measure the total pressure gradient in the vertical pipe, with and without gas injection. The study was conducted with different mixture velocities (0.4 m/s, 0.8 m/s, 1 m/s, 2 m/s, 1.6 m/s, and 3 m/s) as function of the water fraction.

The results of the pressure gradient records with respect to the different mixture velocity without gas injection are presented in Fig. 3. The pressure gradient increases with the increase in mixture velocity. It can be observed that the gradual increase in the dispersed phase (water), by increasing the input water fraction at each constant mixture velocity, leads to a gradual increase in pressure gradient (i.e., between 10 and 90% water fraction) for mixture velocity of 0.4 m/s, 0.8 m/s, and 1 m/s. Therefore, the results showed that at any mixture velocity below 1.6 m/s, the pressure gradient trend linearly increased from pure oil to pure water pressure gradient. However, at mixture velocity 1.6 m/s and above, the trend showed a peak in the pressure gradient due to friction factor (pressure gradient has a sudden drop), in particular at the depth where the flow pattern occurred (water fraction ~ 30%). It can also be seen that at the high mixture velocity of 3 m/s, the peak was more pronounced because of higher shear stress at the pipe wall. This pressure peak could have happened due to the fact that the effective viscosity increased significantly during phase inversion. Indeed, it can be noticed that the effective viscosity increased once the mixture velocity increased. Therefore, the pressure gradient reached a maximum at the phase inversion point (i.e., 30%). Beyond this point, the continuous water phase would gradually increase while the oil phase decreased. This phenomenon correlated well with that observed from different experimental studies in the literature (Nunez et al. 1996).

Oil–water flows with gas injection

The second aim of this study was to investigate the effect of gas (air) injection on phase inversion in a dispersed oil–water flow through a vertical tube. From the first aim of the study, it was clear that the influence of high mixture velocity on the pressure gradient over the pipe during phase inversion was considerable. For simplicity, the experimental results for low and high mixture velocities separately at different gas volume fractions (GVFs) of 0%, 0.52%, 1.04%, 2.05%, 2.56, 3.79, 7.28, and 9.52% will be discussed. Figure 4 shows the pressure gradient as function of water fraction at different mixture velocities (0.4 m/s, 0.8 m/s, 1.6 m/s, 2 m/s, and 3 m/s) and GVFs injected in the tubing. The results show that at ± 30% water fraction, the flow pattern occurred either with or without gas injection. Indeed, most of the figures demonstrate that the pressure drop peak at higher mixture velocities is significantly evident than at lower mixture velocities.

The results also show that the value of the pressure drop peak is not exactly dependent on the amount of the GVF. Even at the lowest GVF of 0.52% at mixture velocity of 2 m/s, the pressure drop peak can even cross the pressure gradient line at the case of low mixture velocity without gas injection around the flow pattern point. Changes were noticed when varying the water fraction at small mixture velocities due to the flow pattern transitions between liquid and gas in vertical flow, but the gradual flow pattern transition is more obvious at higher mixture velocities either with or without gas injection.

The effect of liquid and gas superficial velocity on the total pressure gradient

This experiment was conducted to investigate the effect of gas–oil–water superficial velocity on the total pressure gradient in the vertical pipe. The first experiment was conducted at different gas superficial velocities (0.0 m/s 0.045 m/s, 0.25 m/s, 0.49 m/s, and 0.9 m/s at constant superficial water velocity of 0.4 m/s), by increasing the input superficial oil velocity. The second experiment was conducted at different water superficial velocities (0.18 m/s 0.4 m/s, 0.9 m/s, and 2 m/s at a constant superficial gas velocity of 0.3 m/s), by increasing the input superficial oil velocity. Figure 5 displays the influence of gas–oil–water superficial velocity on the total pressure gradient. The results show that the total pressure gradient exhibited an increase at high superficial gas velocity while this behavior was less evident at low superficial gas velocity. By the increase in superficial oil velocity, the total pressure gradient approaches the pressure gradient of an oil–water two-phase flow.

Furthermore, at a high superficial gas and water velocities, the increase in superficial oil velocity shows minor impact on the pressure gradient because the density of oil phase is getting closer to that of water, as shown in Fig. 6.

Validation and verification of results

There are many mechanisms that could trigger flow pattern transition in the vertical flow. The pressure drop peak obtained in this study, at water friction of ~ 30%, was compared against few correlations available in the literature as stated in Table 2. The comparison showed that all the obtained water fraction values from this study, at the flow pattern point, are very close to the water friction values obtained by other empirical correlations (i.e., ~ 30%). Therefore, the comparison shows that the uncertainty of the flow pattern transition peak (pressure drop peak) in this study is very low.

Conclusion

An experimental study of gas injection in oil–water flow through a vertical pipe has been conducted. The investigation was focused on the effect of gas injection on the phase inversion process between the two liquids in the vertical flow. The investigation started with the flow of oil and water without gas injection, as a reference, to distinguish the influence of gas injection experiments. During the experiments, the phase inversion point and the pressure drop peak were close to a water fraction of ~ 30%, for both water friction direction changes (from water to oil or from oil to water). This pressure peak could have happened due to the significant increase in the effective viscosity during phase inversion. Indeed, the results showed that the effective viscosity increased once the mixture velocity increased. Further investigation is needed to support this explanation.

On the other hand, the results with gas injection showed that gas injection has no effect on the oil or water concentration where phase inversion occurs though gas injection significantly enhanced the pressure drop peak at phase inversion point. Indeed, at mixture velocity of 2 m/s and GVF of 0.52%, the pressure drop peak can even cross the peak point of the oil–water flow without gas injection line.

Further study was conducted to investigate the effect of gas–oil–water superficial velocity on the total pressure gradient in the vertical pipe. The results showed that the total pressure gradient highly increased at high superficial gas velocity and then came to be slow at low superficial gas velocity. By the increase in superficial oil velocity, the total pressure gradient approached the pressure gradient of an oil–water two-phase flow.

References

Arirachakaran S, Oglesby K, Malinowsky M, Shoham O, Brill J (1984) An analysis of oil/water flow phenomena in horizontal pipes. In: SPE production and operations symposium. Oklahoma, US

Ayatollahi S, Narimani M, Moshfeghian M (2004) Intermittent gas lift in Aghajari oil 488 field, a mathematical study. J Pet Sci Eng 42:245–255

Bannwart AC, Rodriguez OMH, de Carvalho CHM, Wang IS, Vara RMO (2004) Flow patterns in heavy crude oil-water flow. ASME J Energy Resour Technol 126:184–189

Blasius, H., 1913. Das Ähnlichkeitsgesetz bei Reibungsvorgängen in Flüssigkeiten, Forschungs-Arbeit des Ingenieur-Wesens 131

Brauner N, Ullmann A (2002) Modeling of phase inversion phenomenon in two-phase pipe flows. Int J Multiph Flow 28:1177–1204

Camponogara E, Nakashima HRP (2006) Solving a gas lift optimization problem by dynamic programming. Eur J Oper Res 2006(174):1220–1246

Descamps M, Oliemans R, Ooms G, Mudde R, Kusters R (2006) Influence of gas injection on phase inversion in an oil–water flow through a vertical tube. Int J Multiph Flow 32:311–322

Descamps M, Oliemans R, Ooms G, Mudde R (2007) Experimental investigation of three-phase flow in a vertical pipe: local characteristics of the gas phase for gas-lift conditions. Int J Multiph Flow 33:1205–1221

Djikpesse HA, Couet B, Wilkinson D (2010) Gas lift optimization under facilities constraints. In: SPE 136977, 34th annual SPE international conference and exhibition, Tinapa, Calabar, Nigeria, 31 July − 7 August, 2010

Glenn OB (2002) The history of the Darcy–Weisbach equation for pipe flow resistance. In: Fredrich A, Rogers J (eds) Proceedings of the 150th anniversary conference of ASCE, Washington, DC. American Society of Civil Engineers, pp 34–43

Gomez V (1974) Optimization of continuous flow gas lift systems. M.S. Thesis. U. of Tulsa: Tulsa, Oklahama, USA

Guet S, Ooms G, Oliemans R, Mudde R (2003) Bubble injector effect on the gas lift efficiency. AIChE J 49(9):2242–2252

Hamedi H, Rashidi F, Khamehchi E (2011) A novel approach to the gas-lift allocation optimization problem. Pet Sci Technol 29(4):418–427

Ho WS, Li NN (1994) Core-annular flow of liquid membrane emulsion. AIChE J 40(12):1961–1968

Hong HT (1975) Effect of the variables on optimization of continuous gas lift system. M.S. Thesis, U. of Tulsa: Tulsa, Oklahama, USA

Khamehchi E, Rashidi F, Karimi B (2009) Nonlinear approach for oil field optimization based on gas lift optimization. Oil Gas Eur Mag 35(4):181–186

Khishvand M, Khamehchi E (2012) Nonlinear risk optimization approach to gas lift allocation optimization. Ind Eng Chem Res 51(6):2637–2643

Mayhill TD (1974) Simplified method for gas lift well problem identification and diagnosis. In: SPE 5151, SPE 49th annual fall meeting, Houston, Texas, USA, October 6 − 9, 1974

Nunez G, Briceno M, Mata C, Rivas H, Joseph D (1996) Flow characteristics of concentrated emulsions of very viscous oil in water. J Rheol 40(3):405–423

Rashidi F, Khamehchi E, Rasouli H (2010) Oil field optimization based on gas lift optimization. In: ESCAPE20, vol 6

Rodriguez OMH, Bannwart AC, de Carvalho CHM (2003) Pressure drop in upward vertical core-annular flow: modelling and experimental investigation. In: 11th international conference on multiphase 2003, extending the boundaries of flow assurance. San Remo, Italy, June 11–13, pp 373–389

Santos O, Bordalo SN, Alhanati FJS (2001) Study of the dynamics, optimization and selection of intermittent gas lift methods—a comprehensive model. J Pet Sci Eng 32:231–248

Yeh G, Haynie F, Moses R (1964) Phase–volume relationship at the point of phase inversion in liquid dispersions. AIChE J 10:260–265

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the LPI, Libya, for supporting this research project. Special thanks to the production technology team of Waha Oil Company, and Mr. Mohamed Own from Harouge Oil Company for their generous assistance and for providing technical support, collaboration and words of encouragement on the success of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author confirms on behalf of all authors that there have been no involvements that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or in the conclusions, or implications.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ganat, T., Hrairi, M. & Regassa, S. Experimental investigation of gas–oil–water phase flow in vertical pipes: influence of gas injection on the total pressure gradient. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 9, 3071–3078 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-019-0703-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-019-0703-0