Abstract

An improved model based on Biot poroelastic theory is presented incorporating the initial seepage flow in the matrix. The proposed model quantifies wave propagation in the oil field development process as VSP, transient well tests, and seismic production technology. Porosity variation, fluid–solid compressibility, and pseudo-threshold pressure gradient in low permeability reservoir are simultaneously considered, resulting in a modified form of continuity and motion equations. Integrating the equations and decomposition for the fluid–solid displacements helps to derive the analytical wave vectors of the fast P, slow P, and S waves in porous media. The sensitivity of affecting factors, such as petrophysical parameter, fluid property, and vibration frequency, on the wave velocity and attenuation is subsequently evaluated. Furthermore, the Biot model can be considered a special situation when the initial flow rate in this model tends to zero. The increase in initial percolating rate, expressed by the ratio of initial flow rate and solid scalar potential, causes an obvious decrease in the fast P wave velocity and an increase in its quality factor. Propagation of the slow P wave and the S wave is scarcely influenced. Low vibration frequency and low permeability also contribute to a large difference between the wave propagation parameters of the improved and Biot models. Cognition of the proportion in the inertia and viscosity effects is helpful in analyzing the complicated multiple mechanisms in wave propagation in the actual developed layer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the development process of low permeability reservoir, acoustic wave or artificial seismic wave inside the wellbore is applied to stimulate fluid percolation and enhance oil recovery in the media saturated with the initial percolating fluid (simplified as seepage media hereafter). This method is called (artificial) seismic production technology or low-frequency vibration oil extraction technology (Cidoncha 2007; Kurawle et al. 2009), which has been tested in many oil fields with certain effects, including increase in injection rate, production rate improvement, and plugging removal. When the technology is used, two processes are involved because of the fluid–solid coupling. One process is wave propagation in the seepage media distinct from that in seismic exploration. The interpretation of wave propagation in seismic exploration is based on general poroelastic theory, with the most classic model proposed by Biot. However, the theory assumes that the media are initially saturated with static fluid. The other process is fluid percolation enhancement by wave-induced solid–fluid relative motion. Research has proven that the wave-induced percolation is relevant in various mechanisms through its influence on the matrix, fluid, and interaction between them.

The latter process has been studied qualitatively or semi-quantitatively with mainly experimental methods. Comprehensive experimental studies on the influence of low-frequency vibration have been conducted by Nikolaevskiy et al. (1996), Dusseault et al. (2000), Ariadji (2005), Wang et al. (2005), Cidoncha (2007), and Liu et al. (2012) in terms of the following factors: whole permeability, O/W relative permeability, capillary force, residual oil saturation, connate water saturation, oil viscosity, porosity, and O/W separation. Nevertheless, fewer studies on dynamic model building and mathematic analysis are conducted than on the experimental method. Luo et al. (1996), Liu et al. (2011), and Shi et al. (2007) analyzed the change in seepage pressure and permeability by incorporating the wave-induced pressure into the motion equation. However, the wave-induced pressure was provided without actual calculation, which made it doubtable or even inaccurate, because the solid–fluid coupling function was not considered. Pan (1999) studied several seepage theory models under wave in his doctoral thesis. In a capillary model, Darcy’s law and Biot theory were combined to analyze the dynamic flow without considering the micro-mechanisms. Huh (2006) reviewed the literature on theoretical modeling with simple immiscible fluid and solid continuity equations, and confirmed that reflecting the complex mechanisms with a simple pore-level model and the well-established capillary number correlation is difficult. Frehner et al. (2007) explained the spectrum separation phenomena, which may have been caused by the difference of source frequency and solid natural frequency with 1D wave mechanical model. Vuong et al. (2015) proposed a numerical approach for modeling incompressible flow through a nearly incompressible elastic matrix under finite deformations and derived a general constitutive law based on thermodynamic principles. Dynamic effects were considered, especially the time- and space-dependent porosity relevant to deformation gradient and pore pressure. In addition, studies analyzing the forces that affect oil droplet adhesion to the pore surface are available to interpret the detachment process in a tube model or plate model (Kostrov and Wooden 2008; Shang et al. 2013). Many micro-mechanisms have yet to be considered because of the high complexity and difference between the influence on the initial percolating fluid and on the initial static fluid. Hence, developing a new seepage model and conducting studies on the changes in seepage behavior or oil redistribution in fluid-saturated media under elastic wave are essential.

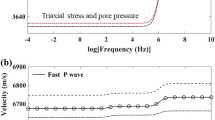

However, related literature on the first process is limited. Most studies about wave propagation have been on applications of civil engineering, mining engineering, marine engineering, seismic exploration, and rock mechanics with the initial static fluid saturation (Fig. 1b). The Biot (1956) model illustrated the rock consolidation under elastic wave and was one of the representative models. Since then, substantial efforts have been exerted (e.g., Dvorkin and Nur 1993; Grant 1994; Cai et al. 2006; Gan et al. 2007; Kumar and Saini 2012; Reine et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2012) to develop a detailed theoretical model or correlation expression around wave velocity, attenuation, rock type, fluid content, and anisotropy. Although the general Darcy law is shown in the motion equation, the way which Darcy equation is incorporated in the models above is substantially different from that in seismic production technology. The former flow or filtration is induced by changes in the stress field and pore pressure caused by the seismic loading. By contrast, the latter is applied in seismic recovery or field tests (Fig. 1a) assisted with fluctuations in the bottom pressure or wellbore stress, thus, assuming that the initial fluid displacement is not zero. Another difference is that the percolation in former models follows Darcy’s law with a fluid acceleration term, whereas the latter may be non-Darcy flow accompanied with a pseudo-pressure gradient (Wang et al. 2016a, b, 2018). Certainly, the equations of the Biot model can still be referenced for the same coexistence of the fluid–solid coupling effect. The initial and wave-induced percolations lead to a more complicated flowing mechanism, and the percolating style in seismic production technology is kept diverse.

Thereby, an insight into the effect of the initial percolating fluid on the wave velocity and its attenuation is required, which is the key work of this study. The elastic wave vector in seepage media can be derived by improving the motion equation and the continuity equation, as well as considering the initial seepage potential. In this study, porosity change and fluid–solid compressibility are not neglected in the derivation process. Comparisons about magnitudes between wave velocities can be an evaluative indicator of accuracy and reliability for the improved model.

Assumption and equations

Assumptions

Most assumptions in the model are the same as in Biot’s theory. The media are saturated with a single-phase fluid. Given the high fluctuation power directly in the seepage formation because of seismic production technology, several assumptions are added. First, the matrix is assumed to be purely elastic with a constant constitutive relation owing to the small vibration force of seismic production technology. Then, the single-phase saturating fluid is assumed to be viscous, Newtonian, and compressible. The media are homogeneous, without any particle suspension or fractures, and only consider the porosity change caused by the compressions of fluid and rock skeleton.

Balance equation of motion

For the existence of initial seepage pressure in low permeability layer, the balance equation of motion for the saturated seepage media under vibration can be rewritten as follows (Zienkiewicz et al. 1980; Zhu et al. 2001; Cui et al. 2010):

where u and \( w \) are the solid displacement and relative fluid displacement respectively; \( \mu \) is the Lame coefficient and equals the shear modulus; \( \lambda \) is another Lame coefficient; \( \alpha \) is the Biot coefficient; \( M \) is a modulus coefficient connected with the matrix modulus; ρ is the average density of porous media; ρf is the fluid density; Pf is the total pore pressure; \( g \) is the gravity acceleration; η is the fluid dynamic viscous; ϕ is the porosity; k is the porous permeability; ω is the vibration frequency; \( \lambda_{0} \) is the quasi-threshold pressure gradient; and \( i_{\text{l}} \) is the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient.

The equation denotes the stress–strain relation of seepage media under the action of elastic wave. However, the seepage is influenced by the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient in the low permeability reservoir, which appears in numerous experimental studies. The physical properties, such as modulus of matrix, pseudo-threshold pressure gradient, and fluid viscosity, are influenced by the variables permeability, porosity, and pressure gradient. In addition, in many other studies on the Biot consolidation problem in civil engineering and ocean engineering, viscosity is substituted by specific gravity. Thus, viscosity should be distinguished in the study on formation seepage.

Mass balance of fluid and solid

Under vibration, the time derivative of real flow rate in the rock with percolating fluid-saturated equals the mass variation per unit time. The mass balance of fluid or solid is obtained as follows:

where \( U \) is the actual fluid displacement, \( U = U_{\text{ff}} + U_{\text{fs}} \); Uff and Ufs are the fluid displacement in original seepage field and additional fluid displacement by fluctuations, respectively; \( \rho_{\text{s}} \) is the solid density; \( q_{0} \) indicates the volumetric inflow or producing rate in the source and sink term.

State equations

The correlation between porosity change, strain, and pore pressure refers to Biot’s model (Biot 1956). Certainly, pore deformation is affected by the effective mobile radius and the proportion of effective flowing pore, as noted in numerous theoretical and experimental studies (Ariadji 2005; Shang et al. 2013; Li 2010; Bedrikovetsky et al. 2011). Therefore, further study on the detailed porosity variation is required. To simplify the calculation, porosity variation can be expressed as a weighted porosity change, \( {\text{d}}\phi^{\prime} = {\text{d}}\phi \cdot \xi \). The porosity variation induced by low-frequency vibration is ignored for simple calculation hereafter and \( \xi \) equals 1.0. Fluid density is expressed as a function of pressure difference and fluid compressibility or modulus in the mechanics of the seepage flow:

where e is the bulk strain of rock; Kf is the bulk modulus of fluid; \( Q_{\text{c}} \) is a coefficient representing the coupling relationship between volume changes of fluid and solid; \( \xi \) is the ratio of the porosity change of porous media caused by low-frequency vibration to the porosity change due to only matrix deformation by the traditional solid–fluid coupling effect.

Modified motion equation and continuity equation considering porosity change and compressibility

In the indoor experimental studies, the changes in physical properties, such as porosity and fluid viscosity, under low-frequency vibrations are sometimes non-ignorable compared with the original media without seismic loading. By contrast, the fluid motion Eq. (1b) and the general continuity equation are derived by Eqs. (2)–(5) with the porosity change and fluid–solid compressibility disregarded. Therefore, the variables in the sum of expansions in Eqs. (2)–(3) can be substituted with those in Eqs. (4)–(5) when porosity change and compressibility are considered. The following equation can then be derived as follows:

Equation (6) is a new whole continuity equation of fluid and solid. The fourth term is the additive volume change that considers porosity change, compressibility, and initial pressure gradient. The total in situ stress is conserved in the inner layer with the application of seismic production technology.

With the gradient of Eq. (4) and the divergence of the right side of Eq. (1b), the Laplacian operator of porous pressure exists in both formulas. The Laplacian operator of porous pressure is deleted, the integration of the formulas with respect to time is performed, and the second-order derivative of fluid swelling–shrinking rate is ignored. A new fluid motion that considers porosity change and fluid–solid compressibility is derived as Eq. (7). The third term on the left side of the equal sign is the additive from Eq. (1b):

Change in the wave vector

Incorporation of the initial seepage potential

Through Helmholtz decomposition (Biot 1956), the displacements of solid and fluid can be written as follows. The original flow field is described as a gradient of fluid potential, considering curlψff = 0:

where the subscript index \( P \) and \( S \) represent the components due to longitudinal wave and transverse wave, respectively; the subscript index \( {\text{s}} \) and \( {\text{f}} \) represent solid and fluid, respectively; the subscript index \( {\text{ff}} \) and \( {\text{fs}} \) are the displacement in original seepage field and additional displacement by fluctuations, respectively; \( \varphi \) and \( \psi \) are the scalar potential in irrotational displacement field and constant-volume displacement field, respectively; the relative displacement of fluid \( w \) is also the sum of \( w_{\text{ff}} \) and \( w_{\text{fs}} \).

According to the relative displacement relation, the scalar potentials of fluid are expressed as follows:

When the pressure gradient is smaller than the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient, the fluid does not flow at the initial state. The wave propagating will be the same as in the Biot model. Consequently, only the situation where the pressure gradient is larger than the pseudo-threshold pressure gradient below is considered.

Substituting above scalar potential into the balance equation of motion Eqs. (1a) and (7), another expression of the Lame motion equation is yielded. The scalar potentials in trigonometric functions are expressed, which are assumed to be Eq. (10) in one-dimensional (1-D) percolation. The potential representing original seepage φff is proportional to the original percolating rate \( q \) and the flow distance \( x \) in 1-D space:

where \( A_{i} \) and \( B_{i} \) are the corresponding amplitudes of potentials in longitudinal wave and shear wave; lp and ls are the wave vectors of longitudinal wave and rotating wave, respectively; \( x \) is the propagating distance of wave; \( q \) is the original percolating rate of unit production layer thickness \( q = Q_{\text{f}} /H \), and when the inertia flow is neglected,\( \frac{{{\text{d}}\varphi_{\text{ff}} }}{{{\text{d}}t}} = - \frac{k}{\eta }\left( {{\text{d}}P_{\text{ff}} - \lambda_{0} x} \right) \),\( \frac{\text{d}}{{{\text{d}}x}}\dot{\varphi }_{\text{ff}} = q \); \( Q_{f} \) is the percolating rate; and \( H \) is the formation thickness.

According to the relation in scalar potentials Eq. (9), the following is obtained:

Derivative of the wave vector

Same with Biot’s theory for wave vector solution, the dispersion equation of P wave or S wave is an equation group related with the coefficients of potential, as [Cij]2×2·[A]2×1=[Y]2×1 and [Clk]2×2·[B]2×1=0, after replacing the displacements with the solutions of scalar potential. The wave vectors of P and S wave, \( l_{\text{p}} \) and \( l_{\text{S}} \), are derived as shown below. When the compressibility term \( \frac{M\eta \omega }{{kK_{\text{f}} }} \) is neglected, the vector of shear wave is equal to that of Biot’s model. When the initial flow rate is neglected, \( q = 0 \), the vector of longitudinal wave is equal to that of Biot’s model:

where

When the flow velocity \( qx \), which can be measured indoor, and the rock vibration amplitude \( u_{\text{S}} \), is known, the concrete wave velocity and wave attenuation (Bai 2006) can be calculated. The rock vibration amplitude \( u_{\text{S}} \) is proportional to the vector of longitudinal wave and amplitude of solid scalar potential, \( u_{\text{S}} = \left| {l_{\text{p}} A_{1} } \right| \). Thus, the value of \( qx/A_{1} \) can be estimated. In the calculation, the vector of longitudinal wave is solved first and substituted into Eq. (10), and then, the vector of shear wave is solved. The vector of shear wave \( l_{\text{S}} \) is derived from several imaginary solutions, a fact that is inconsistent with the previous findings. Therefore, the favorable value (maybe, an average value) of \( l_{\text{S}} \) should be selected to follow the relation \( v_{\text{p}} > v_{\text{S}} > 0 \) and \( Q_{\text{S}} > Q_{\text{p}} > 0 \). \( v_{i} \) and \( Q_{i} (i = P,S) \) are the wave velocity and quality factor of \( i \) wave, respectively. The wave propagation time \( t \) is also assumed to be equal to the wave period to compare the initial fluid displacement and the vibration-induced fluid displacement, of which the ratio is proportional to \( qx/A_{1} \).

Numerical analyses

The wave vector can derive the velocity and attenuation of elastic wave through the seepage media. Further sensitivity analysis under different parameters as petrophysical parameters, fluid property, and vibration frequency is illustrated with numerical simulation. The petrophysical parameters include porosity and permeability, which are affected by vibration frequency. Fluid property mainly refers to viscosity and fluid density. Comparison is made in contrast with the Biot model through the single-variable method. In addition, the relations of modulus and porosity in Ma’s results [Eq. (14)], fit function of pseudo-threshold pressure gradient versus permeability [Eq. (15)], and fit function of viscosity versus vibration frequency [Eq. (16)] are based on the indoor measurement of Ordos natural rocks (Liu et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2011; Zheng et al. 2007):

where KS is the bulk modulus of solid particles; \( K_{\text{b}} \) is the bulk modulus of matrix; \( G \) is the shear modulus; \( \eta_{0} \) is the initial fluid dynamic viscosity; \( C \) is the viscosity reduction coefficient; and \( u_{\text{S}} \) is the given rock vibration amplitude.

Numerical results

The initial specific data of sandstone are shown in Table 1, referring to the parameters of Monterey sand and Ordos sandstone (Kumar and Saini 2012; Li 2010). Attenuation in the seepage media in the figures below is labeled as PER attenuation for the initial pressure gradient, and attenuation in Biot’s model is labeled as Biot attenuation.

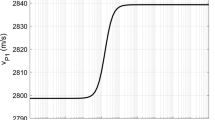

Ratio of initial flow rate and solid scalar potential and vibration frequency The ratio of initial flow rate and solid scalar potential \( qx/A_{1} \) represents the relative size of initial flow and wave-induced flow. It can illustrate the influence of wave-induced fluid–solid relative motion on the whole percolation. As shown in Fig. 2, when the low permeability porous media are saturated with percolating fluid, three waves as the fast and slow P waves and the S wave exist. The responses at \( qx/A_{1} = 0 \) represent predictions from Biot theory. The initial percolation reduces the P wave propagation with a decrease in velocity and an increase in quality factor (Gardner et al. 1964; Jones and Nur 1983). The fast P wave has the largest change owing to the identical orientation of initial percolation and wave-induced forward motion of the fluid and solid (Lo et al. 2009), while the propagations of slow P wave and S wave are scarcely influenced and no longer analyzed. Although the difference is small, the effect by the initial seepage is non-ignorable, especially in circumstances for micro mechanism explanation. Furthermore, a large variation is found with a low vibration frequency. A high frequency accompanies large wave dispersion for the violent relative displacement of fluid–solid and the kinetic energy transformation. The decline in share of the initial percolating energy to the whole energy at high frequency has been the reason for the minor change of P wave velocity from Biot’s result.

The model matches the experimental result for the variation tendency of nonlinear coefficient in Stroisz and Fjær (2011). The non-linear coefficient of elastic wave propagating in drainage porous media is obviously smaller than that in non-drainage media. The drainage and non-drainage media resemble the developed reservoir and the stable undeveloped reservoir, respectively.

Sensitivity of petrophysical parameters The effect of porosity and permeability on wave propagation in seepage media is analyzed in Fig. 3. Both velocity and quality factor in the modified model increase with the permeability, whereas the velocity of Biot’s model barely changes and the attenuation is double logarithmic related with the permeability. The velocity of fast P wave under different permeabilities is obviously lower than that of Biot’s model, and the quality factor is larger than that of Biot’s model. The difference is larger under a lower permeability, because the initial percolation increases the relative displacement velocity. However, the initial percolation under the different porosity in Fig. 4 has only a slight impact on wave propagation. The modulus changes with porosity, causing a different variation trend of velocity versus porosity from the general result. As porosity increases, the modulus of matrix sharply decreases, which is equivalent to an increased effective stress under a constant total stress leading to a closer compaction of solids. Thereby, velocity increases and quality factor decreases with porosity.

Sensitivity of fluid property According to the simplest wave equation, the velocity of P wave is connected with the shear modulus, lame coefficient, and average density. When the solid density and porosity are constant, the fluid density determines the wave propagation. The relation of fluid density versus fast P wave propagation parameter is presented in Fig. 5. The velocity in Biot’s model is slightly larger than that of the modified model with an ignorable variation, whereas the quality factor in two models is of large difference and the same variation tendency. Figure 6 shows viscosity has an apparent effect on wave propagation. Some values of PER attenuation in Fig. 6b are not shown, because the calculated imaginary part of fast P wave vector in the modified model is sometimes positive. A smooth change in wave propagation exists at a small viscosity, whereas the wave velocity and attenuation decrease sharply at a high viscosity as heavy oil. Meanwhile, the initial percolation has a little influence on the relation of viscosity versus propagation parameters.

In summary, a significant difference exists in the dispersion of fast longitudinal wave between the modified model and the Biot model in the initial flow rate, low vibration frequency, and permeability. Fluid viscosity and porosity have weak influence.

Theoretical analysis

The introduction of initial percolation changes the velocity and dispersion of seismic wave during the propagation process. The inertial motion of fluid in particular is strengthened because of the existence of the fluid acceleration term at the right side of Eq. (7). Then, the wave velocity is clearly reduced by the relatively decrease in inertial motion of the solid and the increase in viscosity effect of the fluid. The higher the flow rate, the stronger the inertia effect of fluid compared with the solid. Biot’s model can be considered a special situation when the initial flow rate in the modified model tends to zero. Certainly, the low values of the porosity and permeability lead to a minor difference between wave velocities in two models, which are shown above.

As the fundamental parameters affecting the micro-scale of pore size, \( l^{2} = k/\phi \), change in the porosity or permeability inevitably causes the variation of fast P wave velocity (Muller and Sahay 2010; Feng et al. 2013). Decrease in porosity and increase in permeability result in an increased micro-scale of pore size. The interleaved amplitude of relative fluid–solid motion is augmented. Moreover, the changes in permeability, porosity, and vibration frequency have a simultaneous effect on other parameters. Multiple factors, including micro-scale of pore size, effective stress, pseudo-threshold pressure gradient, and adhesion force, have to be considered to explain the concrete variation tendency. Hence, the mechanisms of wave propagation in an actual layer saturated with initial percolating fluid are more complicated than in Biot theory. Cognition of the changing proportion in the viscosity effect and inertia effect of fluid–solid is also especially helpful for the sensitivity analysis of viscosity and vibration frequency. A high drag force owing to the increased viscosity decreases the relative motions of fluid–solid regardless of the forward or conjugate motions. High frequency leads to a sharply increased inertia motion of solid, regardless of its ability to decrease the fluid viscosity to some extent.

Conclusions

The propagation model of elastic waves in porous media with the initial percolation is established for application of seismic production technology in a low permeability reservoir. Modifying the continuity equation and motion equation and adding the scalar potential of initial flow help to derive the analytical wave vectors of the P- and S waves. The Biot model is be considered a special situation when the initial flow rate in this model tends to zero.

Owing to the coupling of the initial seepage and elastic wave fields, the velocity and quality factor of fast wave are affected by different parameters, such as petrophysical parameters, fluid property, and vibration frequency, wherein the high initial percolating rate, low vibration frequency, and low permeability contribute to a large difference between the modified and Biot’s models.

References

Ariadji T (2005) Effect of vibration on rock and fluid properties: on seeking the vibroseismic technology mechanisms. In: SPE93112

Bai H (2006) Field trial of fluctuating oil extraction technology in low permeability oil field Chang-Heng Periphery in Daqing. Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu

Bedrikovetsky P, Siqueira FD, Furtado CA et al (2011) Modified particle detachment model for colloidal transport in porous media. Transp Porous Med 86:353–383

Biot MA (1956) Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid-saturated porous solid, I. low-frequency range. J Acoust Soc Am 28(2):168–178

Cai YQ, Li BZ, Xu CJ (2006) Analysis of elastic wave propagation in sandstone saturated by two immiscible fluids. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 25(10):2009–2016

Cidoncha JG (2007) Application of acoustic waves for reservoir stimulation. In: SPE108643

Cui ZW, Liu JX, Wang CX et al (2010) Elastic waves in Maxwell fluid-saturated porous media with the squirt flow mechanism. Acta Phys Sin 59(12):8655–8661

Dusseault M, Davidson B, Spanos T (2000) Pressure pulsing: the ups and downs of starting a new technology. JCPT 39(4):13–17

Dvorkin J, Nur A (1993) Dynamic poroelasticity: a unified model with the squirt flow and the Biot mechanism. Geophysics 58:524–533

Feng Q, Wang S, Zhang W et al (2013) Characterization of high-permeability streak in mature waterflooding reservoirs using pressure transient analysis. J Pet Sci Eng 110:55–65

Frehner M, Schmalholz SM, Podladchikov Y (2007) Interaction of seismic background noise with oscillating pore fluids causes spectral modifications of passive seismic measurements at low frequencies. SEG/San Antonio 2007 Annual Meeting, 2007, pp 1307–1311

Gan LD, Yao FC, Du WH et al (2007) 4D seismic technology for water flooding reservoirs. Pet Explor Dev 34(4):437–444

Gardner GHF, Wylue MRJ, Droschak DM (1964) Effects of pressure and fluid saturation on the attenuation of- elastic waves in sands. J Pet Technol 16(2):189–198

Grant AG (1994) Fluid effects on velocity and attenuation in sandtones. J Acoust Soc Am 96(2):1158–1173

Huh C (2006) Improved oil recovery by seismic vibration: a preliminary assessment of possible mechanisms. In: SPE103870

Jones T, Nur A (1983) Effect of temperature, pore fluids, and pressure on seismic wave velocity and attenuation in rock. In: SEG-1983-0583

Kostrov S, Wooden W (2008) Possible mechanisms and case studies for enhancement of oil recovery and production using in situ seismic stimulation. In: SPE 114025

Kumar M, Saini R (2012) Reflection and refraction of attenuated waves at the boundary of an elastic solid with a porous solid saturated with two immiscible viscous fluids. Appl Math Mech 33(6):797–816

Kurawle I, Kaul M, Mahalle N et al (2009) Seismic EOR: the optimization of aging waterflood reservoirs. In: SPE123304

Li W (2010) Wave surface of boundary layer. Exp Ther Fluid Sci 34(7):838–844

Liu J, Pu CS, Liu T et al (2011) Study on the seepage law of formation fluid under the effect of pulse wave. J Xi’an Shiyou Univ (Nat Sci Ed) 26(4):46–49

Liu J, Pu C, Zheng L et al (2012) Experiment research on effects of low frequency vibration wave for crude oil viscosity. Sci Technol Eng 27:7061–7063, 7067

Lo WC, Sposito G, Majer E (2009) Analytical decoupling of poroelasticity equations for acoustic-wave propagation and attenuation in a porous medium containing two immiscible fluids. J Eng Math 64:219–235

Luo Y, Davidson B, Dusseault M (1996) Measurements in ultra-low permeability media with time-varying properties. In: EUROCK-1996-157

Ma Z, Zhou F, Zhao Q (2011) Elastic properties of tight sands in the lower Shihezi formation of Ordos basin. Acta Pet Sin 32(6):1001–1006

Muller TM, Sahay PN (2010) Acoustic signatures of wave-induced vorticity diffusion in porous media. In: SEG Denver 2010 Annual Meeting, pp 2622–2627

Nikolaevskiy VN, Lopukhov GP, Liao Y (1996) Residual oil reservoir recovery with seismic vibrations. In: SPE29155

Pan Y (1999) Reservoir analysis using intermediate frequency excitation[D]. Stanford University, California

Reine C, Clark R, van der Baan M (2012) Robust prestack Q-determination using surface seismic data: part 1—method and synthetic examples. Geophysics 77(1):45–56

Shang X, Pu C, Yu G et al (2013) Study on micro-dynamic mechanism of droplet motion under vibration. Sci Technol Eng 13(8):2166–2169

Shi Y, Pu C, Zhang R (2007) Study on the model of seepage flow in reservoir under low frequency oscillation. J Xi’an Shiyou Univ (Nat Sci Ed) 22(s1):94–96

Stroisz AM, Fjær E (2011) Nonlinear elastic wave propagation in Castlegate sandstone. In: ARMA 11-339

Vuong AT, Yoshihara L, Wall WA (2015) A general approach for modeling interacting flow through porous media under finite deformations. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 28:1240–1259

Wang P, Pu C, Meng D et al (2005) Study of vibration stimulation technology. Oil Field Equip 34(5):28–30

Wang HY, Sun ZD, Charpman M (2012) Velocity dispersion and attenuation of seismic wave propagation in rocks. Acta Pet Sin 33(2):332–342

Wang S, Javadpour F, Feng Q (2016a) Molecular dynamics simulations of oil transport through inorganic nanopores in shale. Fuel 171:74–86

Wang S, Javadpour F, Feng Q (2016b) Fast mass transport of oil and supercritical carbon dioxide through organic nanopores in shale. Fuel 181:741–758

Wang S, Feng Q, Zha M et al (2018) Supercritical methane diffusion in shale nanopores: effects of pressure, mineral types, and moisture content. Energy Fuels 32(1):169–180

Zheng Z, Qin W, Xiao Z et al (2007) Experiment research on the seepage flow and water drive characteristics in low permeability reservoir. J Xi’an Shiyou Univ (Nat Sci Ed) 22(s1):77–79

Zhu JW, He QD, Tian ZY (2001) BISQ-based seismic wave equation in oil-and-water-bearing porous media. Geophs Prospect Pet 40(4):8–13

Zienkiewicz OC, Chang CT, Bettess P (1980) Drained, undrained, consolidating and dynamic behaviour assumptions in soils. Géotechnique 30(4):385–395

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, X., Zheng, L., Chen, C. et al. Velocity and attenuation of elastic wave in a developed layer with the initial inner percolation in the pores. J Petrol Explor Prod Technol 8, 1079–1088 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0468-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-018-0468-x