Abstract

The present investigation observed the effect of current density (j), electrocoagulation (EC) time, inter electrode distance, electrode area, initial pH and settling time on the removal of nitrate (NO3 −) and sulphate (SO4 2−) from biologically treated municipal wastewater (BTMW), and optimization of the operating conditions of the EC process. A glass chamber of two-liter volume was used for the experiments with DC power supply using two electrode plates of aluminum (Al–Al). The maximum removal of NO3 − (63.21 %) and SO4 2− (79.98 %) of BTMW was found with the optimum operating conditions: current density: 2.65 A/m2, EC time: 40 min, inter electrode distance: 0.5 cm, electrode area: 160 cm2, initial pH: 7.5 and settling time: 60 min. The EC brought down the concentration of NO3 − within desirable limit of the Bureau of Indian Standard (BIS)/WHO for drinking water. Under optimal operating conditions, the operating cost was found to be 1.01$/m3 of water in terms of the electrode consumption (23.71 × 10−5 kg Al/m3) and energy consumption (101.76 kWh/m3).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to increased water demand, water shortage is going to get worse in the forthcoming years. Water scarcity is already a fact of life in arid and semi-arid regions where agricultural, domestic and industrial water demands compete for this limited resource. Continuous population growth, rising living standards, rapid industrialization and urbanization have limited the freshwater sources available for agricultural practices (Katz and Dosoretz 2008). Conventionally biologically treated sewage water may not meet the requirements for the discharge and permissible limit of wastewater for its reuse. These processes are, therefore, being ruled out due to requirement of large space, long residence time and skilled technicians. However, even after treatment, secondary treated sewage (STS) effluent contains organic matter and nutrients which cause eutrophication and increase the oxygen demand of the surface water (Sharma 2013).

Sewage treatment deserves ample documentation due to the environmental impact caused by such wastewater if directly discharged into water bodies. In addition, due to an increase in the scarcity of clean water (Aiyuk et al. 2006) there is an urgent need for proper management of available water resources. Some of the goals of environmental protection and resource conservation concepts are the use of treated wastewater, residues emanating therefrom and other treatment by-products (Lettinga et al. 2001; Yi 2001).Conventional treatment methods often induce chemical reactions with the use of coagulants, flocculants and other additives that aid in the removal or sedimentation of inorganic and organic contaminants present in wastewater. It has been reported in the literature that nitrates can be removed from wastewater through their adsorption onto the surfaces of hydroxide precipitates, which are generated from metals and released by the electrodes (Hua et al. 2003; Huanga et al. 2009).

In the electrolytic process of the treatment of biologically treated municipal wastewater (BTMW), Al electrodes are dissolved during electrocoagulation (EC) to produce hydroxides and poly hydroxides of aluminum as coagulants which combine and subvert the organic and inorganic impurities in BTMW.

The electrochemical dissolution has been reported to have stronger affinity to capture the pollutants in the wastewater, causing more coagulation than that from conventional Al coagulants. Additionally, the gas bubbles that evolve due to the water electrolysis can cause flotation of the pollutants and the coagulated materials. Therefore, electro-flotation may also play an important part in an electrolytic cell. Although the Al(OH)3 produced by the anodic Al dissolution is more effective in coagulating the pollutants in wastewater, the passivation of Al anodes and impermeable film formed on cathodes may and does interfere with the performance of electro-coagulation and electro-flotation (Holt et al. 2005). The present study has been focused to find out the treatability of BTMW in terms of NO3 −and SO4 2− removal by EC under various operating conditions using Al electrodes and also to assess the economics of electrode and energy consumption during the EC.

Materials and methods

Collection of BTMW samples

The samples of BTMW were collected from the outlet of activated sludge process (ASP) of the sewage treatment plant (STP), Jagjeetpur, Haridwar (Uttarakhand), India, and brought to the laboratory and then used for EC using Al–Al electrode combination. The pH of BTMW was adjusted before the electrochemical process and was maintained by adding the required amount of H2SO4 (1 M) or NaOH (1 M).The characteristics of BTMW are given in Table 1.

Electrolytic experimental set up

A rectangular Reactor with external dimensions of height = 30 cm, width = 7 cm, length = 11 cm and wall thickness = 10 mm was constructed with glass. The experimental set up consisted of a glass chamber as a Reactor with a capacity of 2.0 L sample. Each time, the BTMW sample of 2.0 L was collected and placed in an electrolytic cell (Chopra and Sharma 2012). Al–Al electrode combination was connected to their respective anode and cathode leading to the D.C Power supply (LMC electronics, India 0–500 V and 0–2 A) and energized for a required duration of time at different voltages and currents. All the experiments were performed at room temperature (30 ± 2 °C) and at a constant stirring speed (100 rpm) to maintain the uniform mixing of BTMW sample during the EC. Before conducting the experiment, the electrodes were washed with water, dipped into diluted HCl (5 % v/v) for 5 min, thoroughly washed with water and then finally rinsed twice with distilled water. Electrodes were dipped into BTMW samples with different electrode areas (80, 120 and 160 cm2) and different inter electrode distances (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5). The different voltages (5–40 V) were applied for different operating times (10–80 min). After applying the particular voltage for a particular time period, i.e., after each batch experiment, the treated samples were allowed to settle for different times (30, 60 and 90 min).

Analytical methods

NO3 −and SO4 2−of BTMW were analyzed before and after EC following the Standard methods (APHA 2005). The calculation of NO3 −and SO4 2− removal efficiency after EC was carried out using the following formula:

where C 0 and C are concentrations of wastewater before and after electrolysis.

Calculation of operating cost

The cost of energy and electrode material was taken into account for the calculation of the operating cost (US $/m3) of EC using the following formula described by Ghosh et al. (2008):

where C energy (kWh/m3) and C electrode (kg Al/m3) are the consumption quantities for the NO3 − and SO4 2− removal. “a” electrical energy price 0.01 US$/kWh, “b” electrode material price 3.5 US$/kg for Al electrode cost due to electrical energy (kWh/m3) was calculated as:

Cost for electrode (kg Al/m3) was calculated using the following equation:

where U is cell voltage (V), I is current (A), t EC is time of electrolysis (s) and v the volume (m3) of BTMW water, M W the molecular mass of aluminum (26.98 g/mol), z the no of electrons transferred (z = 3 for Al) and F is Faraday’s constant (96,487 C/mol).

Results and discussion

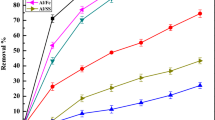

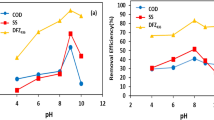

The results on NO3 −and SO4 2− removal efficiency of BTMW by EC at different operating conditions like voltage/current density, EC time, inter electrode distance, electrode area, pH and settling time are shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Effect of current density

Current density was found to be one of the most important parameter of electrolytic process that could drastically affect the removal efficiency of nitrate and sulphate from BTMW. It not only determines the coagulant dose but also the bubble size generation and floc formation which can influence the treatment efficiency of electrolytic technology. As the rate of bubble-generation increases, the bubble size decreases with increase in current density and both of these trends are beneficial in terms of high pollutant removal efficiency by H2 flotation (Can et al. 2003; Kobya et al. 2006; Tezcan Un et al. 2009; Song et al. 2008).With high current, the coagulant dosage rate increased resulting in a greater amount of precipitate in the stable stage. Likewise, the bubble density increases resulting in a greater upward momentum flux and thus there is faster removal of pollutant and coagulant by flotation (Holt et al. 2001). The higher production rate of hydrogen allowed by higher current favored the flotation of the flocculated matter (Khemis et al. 2006).

We observed that the removal percentage of NO3 −and SO4 2−increased progressively with an increase in the current density from 0.16 to 1.68 A/m2 corresponding to its constant voltages (5–40 V), and it was indicated that the maximum removal of NO3 −(46.7 %) and SO4 2− (59.9 %) of BTMW effluent was with the operating conditions of EC time: 30 min, inter electrode distance: 1.0 cm, electrode area: 80 cm2, pH: 7.5 and settling time: 30 min (Fig. 1). This was due to the fact that as the current increased, more Al(OH)3 was produced, which contributed to greater removal of NO3 − and SO4 2− from BTMW by precipitation and flotation. Thus, the higher values of current electrolysed the higher mass of Al during EC, thereby indicating that applied current density to the EC was directly related to the electrocoagulation. (This was in accordance with Faraday’s Law of Electrolysis). It was observed that applied voltage varying from 10 to 25 V, the maximum percent removal of NO3 from drinking water was 84 % at 25 V (Kumar and Sudha 2010). The increase in NO3 removal efficiency has been reported with an increase of the electrical potential from 10 to 40 V for aqueous solution (Malakootian et al. 2011). The cell voltage increases gradually with the increase in current densities as can be expected from the rate of metal oxidation resulting in a greater amount of precipitate being formed during the electrolytic treatment that increases the removal of pollutants from wastewater. There was a slight increase in the temperature with the increase in current densities because of poor conductivity of the solution as also reported by us (Chopra and Sharma 2015) and others (Asaithambi and Matheswaran 2011).

Effect of EC time

It has been observed that as the EC time increases, the concentration of metal ions and their hydroxide flocs increase (Daneshvar et al. 2006; Zaroual et al. 2006; Daneshvar et al. 2007). More bubbles are generated at higher currents that improve the degree of mixing of Al(OH)3 and phenol which enhance floatation ability of the cell with a consequent increase in the phenol removal efficiency (Golder et al. 2007).

The EC time influenced the treatment efficiency of EC. With an increase in EC time, the anodic electrode dissolution led to release of metal ions and the cathode released OH−, which formed their hydroxides into BTMW. The removal of NO3 − and SO4 2− increased progressively with an increase in the EC time from 5 to 40 min with the operating conditions of current density: 1.68 A/m2, inter electrode distance: 1.0 cm, electrode area: 80 cm2, pH: 7.5 and settling time: 30 min. The maximum removal of NO3 − (53.95 %) and SO4 2− (69.15 %) was observed at optimum EC time of 40 min, beyond which there was no significant removal in NO3 − and SO4 2− (Fig. 2).

Effect of inter electrode distance

It has been reported that increasing the distance between electrodes increases electric resistance against the current flowing between anode and cathode (Andrzejm 1980; Dima et al. 2003 ). As the electrode gap becomes less, there is a low mixing of the fluid between electrodes and that remains not sufficient to increase in concentration-polarization layer on electrode surface. With the result, these effects can increase electric potential or resistance of electrodes, thereby diminishing the NO3 − removal efficiency subsequently (Tsai et al. 1997; Lee et al. 2006).

During the present study, inter electrode distance was an effective factor in the EC of BTMW. The percentage removal of NO3 − and SO4 2− increased progressively with decrease in inter electrode distance from 2.5 to 0.5 cm, whereby it exhibited the maximum removal of NO3 − (53.50 %) and SO4 2− (70.29 %) with a distance of 0.5 cm between the electrodes, each having an electrode area of 80 cm2 with the operating conditions of current density: 1.68 A/m2, EC time: 40 min, electrode area: 80 cm2, pH: 7.5 and settling time: 30 min. After that the removal efficiency of NO3 − and SO4 2− was almost constant as the inter electrode distance increased from 0.5 to 1.5 cm (Fig. 3). Similar observations have also been reported by Li et al. (2008) for the removal of COD which decreases with the decrease in distance between electrodes of the same composition. This is because that the shorter distance speeds up the anion discharge on the anode and improves the oxidation. It also reduces resistance, electricity consumption and the cost of the wastewater treatment. Ghosh et al. (2008) have observed that with the increase of inter electrode distance, the percentage removal of dye products from wastewater decreased. At a lower inter electrode distance, the resistance encountered by the current flowing in the solution medium decreased, thereby, facilitated the electrolytic process resulting in enhanced dye removal. Nandi and Patel (2013) also observed that with weak inter electrode distance of 1 cm, there was maximum dye removal of 99.59, 89.98 and 76.14 % for three different current densities of 41.4, 27.8 and 13.9 A/m2, respectively.

Effect of electrode area

An increase in the electrode area causes corresponding increase of coagulants. The entire effectiveness of the coagulation process depended on the appropriate amount of coagulant (Daneshava et al. 2005). Logistical relationship between electrode geometric area (AG) and copper removal efficiency indicated that an increase in copper removal was related to an increase in AG, reaching to an optimal value of 35 cm2 with an asymptotic value of ≈80 % (Escobara et al. 2006). The removal efficiency of TD, BOD and COD has been attributed to a greater EA that produced larger amount of anions and cations from the anode and cathode. The greater the EA, the greater the rate of flock formation, which in turn influenced the removal efficiency of ET (Chopra and Sharma 2013). Similarly, in the present study it was observed that with an increase in electrode area from 80 to 160 cm2, the current density increased from 1.68 to 2.65 A/m2 with a corresponding constant voltage of 40 V which resulted in an increase in the removal % of NO3 − and SO4 2−. The maximum removal of NO3 − (61.14 %) and SO4 2− (77.94 %) was achieved with maximum electrode area of 160 cm2 with the following operating conditions of current density: 1.68 A/m2, EC time: 40 min, inter electrode distance: 0.5 cm, initial pH: 7.5 and settling time: 30 min (Fig. 4).

Effect of pH

pH is an important operating factor influencing the electro-coagulation process (Lin and Chen 1997; Chen et al. 2000; Gurses et al. 2002; Kobya et al. 2003). It is the removal efficiency of colloidal particles in the pH range of 4–7 that leads to the formation of amorphous hydroxide precipitates and other aluminum hydroxo complexes with hydroxide ions and polymeric species (Bayramoglu et al. 2004). It has been shown that pH is an important factor in EC and its variation is usually caused by the solubility of metal hydroxides. The pH of the effluent increases for acidic influent after electro-coagulation and decreases for alkaline influent. The hydroxy radicals which may be produced as a result of dissociation of water under certain electrochemical reactions are known to be one of the most reactive aqueous radical species and these radicals have the ability to oxidize almost all of the organic compounds because of their high affinity value of 136 kcal (Chen and Hung 2007). In fact, hydroxyl radical is an extremely potent oxidizing agent with a short half-life, and is able to oxidize organic compound by hydrogen abstraction reaction, by redox reaction and/or by electrophilic addition to pi systems resulting in a cascade of free radical reactions leading to oxidative degradation of pollutants (Oturan 2000). However, electrolysis using Al electrodes leads to the formation of ionic complexes, and formation of hydroxyl radical, to the best of our knowledge, has not been demonstrated. The Al3 + ions on hydrolysis generated the aqueous complex Al (H2O) 3+6 , which was predominant at pH < 4. Between pH 5 and 6; the predominant hydrolysis products were Al(OH) +2 and Al(OH) +2 between pH 5.2 and 8.8, the solid Al(OH)3 was more prevalent and above pH 9, the soluble species Al(OH)4 were the predominant and were the only species present above the pH 10 (Gomes et al. 2007).

The removal of NO3 − and SO4 2− from BTMW effluent with its different initial concentrations of pH 5–8.5, operating conditions of current density: 2.65 A/m2, EC time: 40 min, inter electrode distance: 0.5 cm, electrode area: 160 cm2 and settling time: 30 min indicated that the removal of NO3 − increased from 57.66 to 63.14 % with an increase in the pH from 5 to 7.0, while the removal of SO4 2− increased from 71.78 to 78.49 % with an increase in pH from 5 to 7.5. However, the increase in pH of BTMW to more than 7.0 decreased the % removal of NO3 −, whereas the removal % of SO4 2− decreased with the increase in pH more than 7.5 (Fig. 5).

Effect of settling time

The effect of settling time on removal efficiency after EC has not been given due consideration so far. There appears to be little work with regard to the settling time on the BTMW treatment during electrolysis. During the present study, it was interesting to note that the removal efficiency with the constant operating conditions of current density: 2.65 A/m2, EC time: 40 min, electrode area: 160 cm2 and pH: 7.5 improved with an increase of settling time from 30 to 90 min of BTMW. The maximum removal of NO3 − (63.21 %) and SO4 2− (79.98 %) was found to be at the settling time of 60 min. Beyond which there was almost no more significant removal (Fig. 6). However, our earlier study has also reported the maximum removal of COD (92.35 %) at the settling time of 60 min and that of BOD (84.88 %) at the settling time of 30 min (Sharma and Chopra 2013). It was also interesting to note that the EC of BTMW brought down the concentration of NO3 − from 123.45 to 36.47 mg/l to the desirable limit (45 mg/l) of BIS (1991) standard of drinking water. Though the concentration of SO4 2− of BTMW was already within permissible limit of BIS, EC further brought down the removal of SO4 2− from 142.34 to 28.92 mg/l.

Economic evaluation

Electrical energy and electrode consumption are the important parameters in the economic evaluation of EC process. In EC process, the operating cost mainly included the cost of electrodes and electrical energy as well as labor, maintenance, sludge dewatering and their disposal. The removal of NO3 − and SO4 2− during EC, energy consumption increased from 64.32 to 101.76 kWh/m3 with an increase in electrode area (80–160 cm2) and current density (1.68–2.65 A/m2) that resulted in increase of the electrode consumption from 14.985 × 10−5 to 23.71 × 10−5 kg/m3. The cost was found to be 1.01 $ on the basis of energy and electrode consumption with the optimum operating conditions (Table 2).

Conclusion

The removal of NO3 −and SO4 2− from BTMW using Al electrodes was found to depend on voltage/current density, EC time, inter electrode distance, electrode area and initial pH during the EC. The maximum removal of NO3 − (63.21 %) and SO4 2− (79.98 %) was with the optimal operating conditions of current density: 2.65 A/m2, EC time: 40 min, electrode area: 160 cm2 and pH: 7.5. The higher values of current electrolysed the higher mass of Al during EC, thereby indicating that applied current density to the EC was directly related to the electrolysis. The EC removed the concentration of NO3 − from the BTMW below to the desirable limit of the BIS/WHO standards of drinking water. The operating cost was 1.01 US $/m3 in terms of energy and electrode consumption. There was no need of pH adjustment of the BTMW during EC as the optimal removal of NO3 − and SO4 2− was close to the neutral pH of 7.0

References

Aiyuk S, Forrez I, Kempeneer DL, Haandel A, Verstraete W (2006) Anaerobic and complementary treatment of domestic sewage in regions with hot climates—A review. Bioresour Technol 97:2225–2241

Andrzejm B (1980) Electrocoagulation of biologically treated sewage. In: 35th Industrial waste conference proceeding, p 541

APHA (2005) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 21st edn. American Public Health Association, Washington

Asaithambi P, Matheswaran M (2011) Electrochemical treatment of simulated sugar industrial effluent: optimization and modeling using a response surface methodology. Arab J Chem. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2011.10.004

Bayramoglu M, Kobya M, Can OT, Sozbir M (2004) Operating costs analysis of electrocoagulation of textile dye wastewater. Sep Purif Technol 37:117–125

BIS (1991) Specifications for Drinking Water, IS: 10500. Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi

Can OT, Bayramoglu M, Kobya M (2003) Decolorization of reactive dye solutions byelectrocoagulation using aluminum electrodes. Ind Eng Chem Res 42:3391–3396

Chen G, Hung YT (2007) Electrochemical wastewater treatment processes, in handbook of environmental engineering, volume 5: advanced physicochemical treatment technologies, L.K. Wang, Y-T. Hung, and N.K. Shammas, The Humana Press Inc., Totowa, pp 57–105

Chen X, Chen G, Yue PL (2000) Separation of pollutants from restaurant waste water by electrocoagulation. Sep Purif Tech 19:65–76

Chopra AK, Sharma AK (2012) Efficiency of turbidity and BOD removal from secondarily treated sewage by electrochemical treatment. J Appl Nat Sci 4(2):304–309

Chopra AK, Sharma AK (2013) Removal of turbidity, COD and BOD from secondarily treated sewage water by electrolytic treatment. Appl Water Sci 3(1):125–132

Chopra AK, Sharma AK (2015) Effect of electrochemical treatment on the COD removal from biologically treated municipal wastewater. Desalin Water Treat 53(1):41–47

Daneshava N, Oladegaragoze A, Djafarzadeh N (2005) Decolorization of basic dye solutions by electrocoagulation: an investigation of the effect of operational parameters. J Hazard Mater 129:116–122

Daneshvar N, Oladegaragoze A, Djafarzadeh N (2006) Decolorization of basic dye solutions by electro coagulation: an investigation of the effect of operational parameters. J Hazard Mater B 129:116–122

Daneshvar N, Khataee AR, Amani Ghadim AR, Rasoulifard MH (2007) Decolorization of C.I. acid yellow 23 solution by electrocoagulation process: investigation of operational parameters and evaluation of specific electrical energy consumption (SEEC). J Hazard Mater 148:566–572

Dima GE, de Vooys ACA, Koper MTM (2003) Electro catalytic in acid solutions. J Electro anal Chem 15:554–555

Escobara C, Cesar SS, Toral M (2006) Optimization of the electrocoagulation process for the removal of copper, lead and cadmium in natural waters and simulated wastewater. J Environ Manag 81(4):384–391

Ghosh D, Medhi CR, Solanki H, Purkait MK (2008) Decolorization of crystal violet solution by electro coagulation. J environ prot sci 2:25–35

Golder AK, Samanta AN, Ray S (2007) Removal of trivalent chromium by electrocoagulation. Sep Purif Technol 53:33–41

Gomes JAG, Daida P, Kesmez M, Weir M, Moreno H, Parga JR, Irwin G, Mc Whinney H, GradyT Peterson E, Cocke DL (2007) Arsenic removal by electrocoagulation using combined Al-Fe electrode system and characterization of products. J Hazard Mater 139(2):220–231

Gurses A, Yalcin M, Dogar C (2002) Electro coagulation of some reactive dyes: a statistical investigation of some electrical variables. Waste Manag 22:491–499

Holt PK, Barton G W, Mitchell C A (2001) The role of current in determining pollutant removalin a batch electrocoagulation reactor. In: 6th World congress of chemical engineering, conference media CD, Melbourne, Australia

Holt PK, Barton GW, Mitchell CA (2005) The future for: electrocoagulation as a localized water treatment technology. Chemosphere 59:355–367

Hua CY, Loa SL, Kuan WH (2003) Effects of co-existing anions on fluoride removal in electrocoagulation (EC) process using aluminum electrodes. Water Res 37:4513–4523

Huanga CH, Chen L, Yang CL (2009) Effect of anions on electrochemical coagulation for cadmium removal. Sep Purif Technol 65:137–146

Katz I, Dosoretz CG (2008) Desalination of domestic wastewater effluents: phosphate removal as pretreatment. Desalination 222:230–242

Khemis M, Leclerc JP, Tanguy G, Valentin G, Lapicque F (2006) Treatment of industrial liquid wastes by electro-coagulation: experimental investigations and an overall interpretation model. Chem Eng Sci 61:3602–3609

Kobya M, Can OT, Bayramoglu M (2003) Treatment of textile waste waters by electrocoagulation using iron and aluminum electrodes. J hazard Mat B 100:163–178

Kobya M, Demirbas E, Can OT, Bayramoglu M (2006) Treatment of levafix orange textile dye solution by electrocoagulation. J Hazard Mat 132:183–188

Kumar NS, Sudha Goel (2010) Factors influencing arsenic and nitrate removal from drinking water in a continuous flow electro coagulation (EC) process. J Hazard Mat 173:528–533

Lee SM, Maken S, Jang JH, Park KN, Park JW (2006) Development of physico chemical nitrogen removal process for high strength industrial waste water. Water Res 40:975–980

Lettinga G, Lier Van, Van JB, Buuren JCL, Zeeman G (2001) Sustainable development inpollution control and the role of anaerobic treatment. Water Sci Technol 44:181–188

Li Xu, Wei Wang, Mingyu Wang, Yongyi Cai (2008) Electrochemical degradation of tridecanedicarboxylic acid wastewater with tantalum-based diamond film electrode. Desalination 222:388–393

Lin SH, Chen ML (1997) Treatment of textile wastewater by electrochemical methods for reuse. Water Res 31:868–876

Malakootian M, Yousefi N, Fatehizadeh A (2011) Survey efficiency of electrocoagulation on nitrate removal from aqueous solution. Int J Environ Sci Tech 8:107–114

Nandi BK, Patel S (2013) Effects of operational parameters on the removal of brilliant green dye from aqueous solutions by electrocoagulation. Arab J Chem. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.11.032

Oturan MA (2000) An ecologically e€ective water treatment technique using electrochemically generated hydroxyl radicals for in situ destruction of organic pollutants: application to herbicide 2,4-D. J Appl Electrochem 30:475–482

Sharma AK (2013) A study on electrolytic technology for purification of secondarily treated sewage-waste effluents. Ph.D. Thesis, Gurukula Kangri University, Haridwar

Sharma AK, Chopra AK (2013) Removal of COD and BOD from biologically treated municipal wastewater by electrochemical treatment. J Appl Nat Sci 5(2):475–481

Song S, Yao J, He Z, Qiu J, Chen J (2008) Effect of operational parameters on thedecolorization of C.I. Reactive blue 19 in aqueous solution by ozone-enhanced electrocoagulation. J Hazard Mater 152:204–210

Tezcan Un U, Koparal AS, Bakir Ogutveren U (2009) Electrocoagulation of vegetable oil refinery wastewater using aluminum electrodes. J Environ Manage 90:428–433

Tsai CT, Lin ST, Shue YC, Su PL (1997) Electrolysis of soluble organic matter in leachate from landfills. Water Res 31(12):3073–3081

Yi Q (2001) A sustainable technology for developing country anaerobic digestion. In: Proc. 9th World Congress on anaerobic digestion––anaerobic conversion for sustainability (Part 1), Antwerp, Belgium, pp 23–30

Zaroual Z, Azzi M, Saib N (2006) Contribution to the study of electrocoagulation mechanism inbasic textile effluent. J Hazard Mat 131(1–3):73–78

Acknowledgments

The University Grants Commission, New Delhi, India, is acknowledged for providing the financial support in the form of UGC Research Fellowship (F.4-1/2006 (BSR) 7-70/2007 BSR) to Mr. Arun Kumar Sharma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, A.K., Chopra, A.K. Removal of nitrate and sulphate from biologically treated municipal wastewater by electrocoagulation. Appl Water Sci 7, 1239–1246 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-015-0320-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-015-0320-0