Abstract

Introduction

Anti-asexual bias has received limited but growing public and academic attention. Examining prejudice towards asexuals expands the depth of intergroup and intragroup relation research.

Methods

The current study is aimed at clarifying anti-asexuality bias by examining attitudes towards asexual individuals with a multi-item measure in Greek culture. An exploratory cross-sectional study was conducted between April 4 and May 4, 2021, via an online survey. One hundred and eighty-seven undergraduate students participated in the current study. Bivariate correlation was used to explore the associations between variables of interest. Next, hypotheses were examined by performing a bootstrapping analysis for parallel multiple mediation models.

Results

The findings of this study support the role of context-related socio-cultural (religiosity, political positioning) and social-psychological factors (adherence to social norms) in predicting participants’ anti-asexual bias.

Conclusions

This study draws attention to the stigmatization of asexuality. It warns professionals, policymakers, and social agents about the dominant sexually normative socio-cultural context that may negatively affect asexuals’ lives.

Policy Implications

Providing information about the supporting base of outgroup dislike might be a way of promoting social change. Stakeholders and professionals who influence people’s lives (educators, health professionals) should be aware of possible stigmatization to no further stigmatize asexual individuals, ensuring they do not internalize and project these stereotypical assumptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There has been an increase in systematic research on the subject of asexuality along with a shift from a pathological to a more affirming viewpoint (e.g., Bogaert, 2004; Bulmer & Izuma, 2017; Gressgård, 2013; Gupta, 2017; Van Houdenhove et al., 2013; Vu et al., 2021; Yule et al., 2017). Johnson, in 1977, used the term asexuals and defined it as “men and women who, despite their physical or emotional condition, sexual history and relational status, or ideological orientation, chose not to engage in sexual activity” (p.99). The Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), a forum where asexuals discuss their experiences, was founded in 2001 and played a vital role in the renewed scientific interest in asexuality (Brotto et al., 2010). The absence of sexual attraction to other people was the original definition of asexuality given by AVEN. This definition is widespread in the scientific community (Van Houdenhove et al., 2017), the asexual community (Jones et al., 2017), and the public (Vu et al., 2021). This definition, however, does not fully capture the predominant views and inclinations in the asexual community (Carrigan, 2011). Those who identify as demisexuals and experience sexual desire due to an emotional connection with others and those who identify as gray-sexuals, which experience minimal levels of sexual attraction, are examples of this variation (Carrigan, 2011; Decker, 2015).

The fact that asexuals are making themselves more visible (Chasin, 2015) in a primarily sexualized society leads to new and mostly understudied intergroup dynamics between sexual and asexual individuals (Hoffarth, 2015) and specifically anti-asexual prejudice (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). Anti-asexual prejudice probably stems from considering asexuality as a weakness and/or a flaw (a deficiency) since it constitutes a nonnormative and nonheterosexual sexual orientation (Herek, 2010). Anti-asexual prejudice concerns sexual orientation and differs from antipathy towards people not in committed relationships (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). Therefore, anti-asexual prejudice may be considered a subtype of sexual prejudice. Asexuals may be disliked not for doing something but disapproved of for not complying with the prevalent norms. Such biases can inform researchers about the supporting base of outgroup dislike (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). To the researcher’s knowledge, asexuality has received no scientific attention in the Greek context. Also, there are no research data concerning the experience of asexual people in Greece. In addition, this study also promotes research on attitude-based discrimination towards asexuality and examines the impact of context-related socio-cultural factors on stigma formation.

Defining Asexuality

Different theoretical approaches have been used to define asexuality. Initially, asexuality was labeled as category X by Kinsey et al. (1948, p.407), meaning individuals “without socio-sexual contacts or reactions.” Past research considered asexuality to be a lack of sexual activity (Rothblum & Brehony, 1993), a lack of sexual desire (Prause & Graham, 2007), a lack of sexual attraction (Bogaert, 2004), and having little to no sexual attraction while self-identifying as asexual (Chasin, 2011). Regarding experiences, intersecting identities (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, and romantic identities; Kelleher & Murphy, 2022), and expressions, asexuality is widely diverse, like any other sexual orientation. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that several definitions have emerged linked to the asexual experience (Brunning & McKeever, 2020; Zheng & Su, 2018; Vu et al., 2021). Asexuality is characterized as having low to no sexual attraction in the context of human sexuality (Bogaert, 2015; Greaves et al., 2017; Robbins et al., 2016). “An asexual person is a person who does not experience sexual attraction,” states the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN). However, sexual attraction, desire, arousal, and activity change over a person’s life and are influenced by various contextual factors. This suggests that sexual identity can change throughout time and may be affected by the environment, at least in part (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). Asexuality and other sexual identities and behaviors are commonly considered in terms of broad spectrums (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). The spectrum of asexual identities includes grey-asexual and demisexual, which describe limited sexual desire under particular conditions or until specific standards are reached (Dawson et al., 2016).

Asexuality is viewed as a sexual orientation by the majority of asexual organizations (e.g., the Asexual Visibility and Education Network; AVEN, 2021), which also matches the current agreement among scholars (Chasin, 2011; Deutsch, 2018; Van Houdenhove et al., 2017). More specifically, asexuality is a sexual orientation describing individuals who do not experience sexual attraction (AVEN, 2021). According to the relevant scholarly literature, the asexuality concept is equivocal. Asexuality has been described in the literature in a variety of ways, including as a persistent lack of sexual attraction towards others and as a sexual orientation characterized by that lack of attraction (Brotto & Yule, 2011). Some researchers have challenged this definition by asserting that people can move into and out of this category (Hinderliter, 2009).

The question of whether asexuality is genuinely an orientation is complicated and influenced by the fact that the rhetoric surrounding orientation has significant social and political implications. Many asexuals reject the notion that being asexual means lacking a sexual orientation since they find it uncomfortable to be described negatively or in terms of absence. If a sexual identity can be classified as an orientation, obtaining recognition and protection in today’s social environment is also simpler. This may happen because “orientation” evokes a distinct and natural category (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). One important division within the asexual community is between those who experience romantic attraction (romantic asexuals) and those who do not (aromantic asexuals). People in the former category are identified as heteroromantic, biromantic, homoromantic, or polyromantic (Carrigan et al., 2013). Another distinction has to do with how asexual people react to sexual activity. While some asexual people are indifferent to sex, others vehemently oppose it to differing degrees (Carrigan et al., 2013). Asexual people may also experience some sexual desire or pleasure, or they may engage in some sexual acts, whether that is with themselves or with others (Brotto & Yule, 2011; Brotto et al., 2010). In addition, there is variation in the significance of sexual inactivity since, for some asexuals, this is an important aspect of their asexuality, while for others, this may not be essential to their asexuality as they may engage in sex for several reasons (Brotto et al., 2015; Bulmer & Izuma, 2017; Cryle & Moore; Gupta, 2015a). Furthermore, even though most asexuals report a lifelong/primary asexuality (meaning that they have always felt that way), others report various reasons for their asexuality (for more details, see Bulmer and Izuma (2017)). It is also suggested that a way to understand asexuality is as a meta-construct equivalent to sexuality that encompasses constructs of self-identity, self-attraction, desires, fantasies, and behaviors, even though not everyone will relate to these constructs similarly (Chasin, 2011).

Other scholars have provided more political definitions of asexuality to accommodate the concept’s complexity. Cerankowski and Milks (2010) suggest a “feminist mode of asexuality” which “… might consider as asexual someone who is not intrinsically/biologically asexual (i.e., lacking a sexual drive) but who is sexually inactive, whether short-term or long-term, not through a religious or spiritual vow of celibacy but through feminist agency” (p. 659). According to Chasin (2011), those who identify as asexual are formed by the asexual community’s languages and practices, which impact how asexual people perceive and experience their asexuality. Furthermore, Przybylo (2011) challenges both conventional definitions of asexuality, such as the absence of desire, and the essentialist definitions of asexuality. Instead of focusing on what asexuality does not do, this author suggests conceptualizing it in terms of what it does (such as reconfiguring relational networks). Asexuality can be understood as “queer” in the sense that it responds to the ableist ideas that bind compulsory sexuality with normality, or the idea that to be “healthy” and “normal” means to have and desire sex (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). This directly challenges some of the more restrictive notions of asexuality, such as Bogaert’s (2012) claim that asexuality must be a lifelong orientation to qualify as an orientation or the DSM-5’s statement that for women to qualify as “asexual” and avoid the label of female sexual interest/arousal disorder, they must have never felt sexual attraction. In this way, feminism and queer theories of asexuality challenge a dominant medical paradigm that tends to pathologize a lack of sexual desire (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). Definitions of asexuality, emerging from the asexual, or “ace” community, challenge compulsory sexuality, or the idea that sex and sexuality are inherent aspects of being human, suggesting that sexual attraction is not an innate feature of intimate or interpersonal life (Brunning & McKeever, 2020; Zheng & Su, 2018).

To summarize, research data show that asexuals constitute a highly heterogeneous group (Brotto et al., 2010), presenting significant fluctuation as regards relational status, sexual experiences, and sexual identity. While feminist and queer researchers have investigated the political, intersectional, and resistance-based possibilities of asexuality, challenging limiting definitions of asexuality and requesting for asexuality to be considered alongside desexualization scientific research have alternated between pathologizing asexuality and legitimizing it as a sexual orientation (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). Therefore, it is significant to broaden and pluralize the definitions of asexuality to accommodate sexual fluidity or the idea that asexuality can evolve throughout an individual’s lifetime (Brunning & McKeever, 2020). The development of asexual identities and the expansion of online asexual communities provide several empirical and theoretical issues for researchers in psychology and allied disciplines that are only now beginning to be addressed (Carrigan et al., 2013).

Opposition to Sex Normativity

Currently, asexuality has become a topic of local and global activism to abolish the stigma, break the taboo around it, and highlight how it has been stigmatized in settings that uphold compulsory sexuality. Compulsory sexuality is defined as “the ingrained cultural presumption that some form of sexual attraction defines everyone” (Emens, 2014; Gupta, 2015a, b). That is, “the assumption that all people are sexual as well as the social norms and practices that both marginalize various forms of nonsexuality, such as a lack of sexual desire or behavior, and compel people to experience themselves as desiring subjects, take on sexual identities, and engage in sexual activity” (Gupta, 2015a, p. 132). This societal presumption that everyone should desire sexual activity or intimacy negatively influences the asexual population (Deutsch, 2018; Kelleher et al., 2023). Asexuality challenges the widely held belief that sexual behavior is necessary for humans (Gupta, 2017). The term “compulsory sexuality” is used by Gupta (2015a) to refer to these presumptions that marginalize the lives of asexual people.

Asexuality blurs the distinction between “sexual” and “nonsexual” interactions and undermines the value placed on them by society. Scherrer’s (2008) arguments have been echoed by other academics, who contend that asexuality may put our “sex-normative culture,” “sexual normativity,” and society’s “sexual assumption” under scrutiny (Carrigan, 2011). Kim (2010) challenges the widely held belief that engaging in sexual activity is necessary for a “healthy lifestyle.” Przybylo (2011) contends that many asexual activists fall short of upending what she calls “sexusociety” by pushing for public acceptance of asexuality as an innate sexual preference. According to the Ace community, asexuality is an orientation that crosses all other sexual identities. However, even though asexual identity could be viewed as a part of queer and LGBTQ2A + (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, questioning/queer, two-spirited, allied/asexual/aromantic/agender, and others) organizing, numerous asexual people claim to be ostracized from LGBTQ2 + and queer spaces (Ginoza et al., 2014). Finally, according to Przybylo (2011, p.452) “in its current reactive, binarized state, asexuality functions to anchor sexuality, not alter its logic.” Thus, some scholars argue that the current asexual activism does not challenge contemporary sexual norms.

Attitudes Towards Asexuality

Asexuals are stigmatized as the target of prejudice, discrimination, and reduced contact intentions (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). Researchers from a variety of disciplines have offered proof of “asexphobia” or “anti-asexual bias/prejudice,” according to which asexuals are perceived as “deficient,” “less human,” and despised (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012, p.740). It is crucial to be aware of views towards asexual people, given the adverse effects that normative assumptions have on asexual people. “Self-identification [as asexual] places the individual in a threatening situation that has to be managed” (MacNeela & Murphy, 2014, p. 800). For an asexual person, dealing with threats like denial narratives and microaggressions frequently necessitates highly restricted disclosure, even among close friends and immediate family (Vu et al., 2021).

Research data report that asexuals are the targets of heteronormative discrimination (Chasin, 2011; MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). Specifically, asexuals may face denial or disbelief of their asexual self-identification (MacNeela & Murphy, 2014), difficulties in relationships (Carrigan, 2011), and pathologization (Gupta, 2017; Robbins et al., 2015). In addition, asexuals may engage in sexual behavior with romantic partners due to the pressure to please (Carrigan, 2011), to show love (Van Houdenhove et al., 2015), or due to peer pressure and desire to be normal (Dawson et al., 2016). Furthermore, the negative influence of current sexual norms and beliefs on the lives of asexual individuals is underlined in studies reporting that asexuals face higher instances of anxiety disorders and interpersonal problems than the sexually “active” population does (Yule et al., 2013). As MacInnis and Hodson (2012) argue, heterosexuals see asexuals as “less human” than other sexual minorities. Thus, for all the reasons mentioned above, asexuals may be discouraged from coming out, even to their closest friends or romantic partners.

Considering asexuality negatively is reflected in beliefs entrenched in the assumption that sexuality is superior to asexuality, acknowledging asexuality more as a problem rather than an established sexual orientation (Chasin, 2015). As Przybylo (2011) argues, the sexual/nonasexual society is very likely to suppress asexual individuals since nonsexual relationships are underestimated in a nonasexual context, and not wanting sex may be understood as a possible mental disorder. Moreover, as asexuals fail to be involved in the heteronormative sexual desire (e.g., flirt and/or dress to be hetero-sexy), the dominant heterosexual societal structure may consider asexual people as “others” who resist the (hetero)sexual model of masculinity/femininity (Chasin, 2015). Furthermore, as asexuals do not engage in sexual activities in a heteronormative way, they may be considered to be violating traditional gender norms (Chasin, 2015). In this light, the absence of sexual attraction and sexual activities among asexuals may be considered transgressing both female and male norms (Hoffarth et al., 2015). Thus, because asexuality could threaten society’s sexual normativity (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012), anti-asexual prejudice is conceptually unparalleled with more commonly studied prejudices such as racism (Hoffarth et al., 2015).

The “differences as deficit model” (Herek, p. 210) provides a theoretical explanation for this stigmatization: those who deviate from normal or typical orientations find themselves the targets of prejudice since they oppose deeply held beliefs about sexuality and relationship formation (Chasin, 2013). According to several scholars, Western society continually favors sexual desires, sexual activities, and sexual identifications while at the same time excluding distinct forms of nonsexuality (Chasin, 2013; Emens, 2014). It seems that the asexual community formation poses a threat to the existing contemporary Western sexual norms and the society-wide system of “compulsory sexuality” and sexual attraction as a universal motivating force or as an essential component of adult identity (Bulmer & Izuma, 2017; Cryle & Moore; Gupta, 2015a, b). The pathologization, microaggressions, and denial narratives that asexual persons encounter prove the harmful effects of compulsory sexuality (Hoffarth et al., 2016).

MacInnis and Hodson’s study (2012) showed that, compared to heterosexual, bisexual, and gay groups, asexual people were rated less favorably on a thermometer scale. When asked about their intentions to contact asexual people in the future, heterosexual participants expressed more significant discomfort. In addition, there was a direct association between anti-asexual attitudes and higher levels of religious fundamentalism (MacInnis & Hodson, 2012). The work of Hoffarth et al. (2016), who developed the attitudes towards asexuals (ATA) measure, and Vu et al. (2021) repeated the initial findings of MacInnis and Hodson (2012). Hoffarth et al. (2016) also showed that lower anti-asexual bias was associated with increased knowledge, awareness, and intergroup contact with asexual people. According to the study on the anti-asexual bias that has been summarized above, many asexual people are likely to endure substantial marginalization, which may affect their mental health (Deutsch, 2018).

Scholars who have studied asexuality have claimed that, in certain ways, the development of asexuality as a sexual identity challenges prevalent conceptions of sexuality and interpersonal interactions. Asexuality, for instance, challenges the ingrained social presumption that “all humans experience sexual desire” (Scherrer, 2008, p. 621). In Gupta’s (2017) study, asexual-identified participants discussed their resistance to making sexuality the center of their existence and their fight to make asexuality more visible. Overall, asexual individuals live in a culture that prioritizes sex and romantic relationships. Although they may not appear to be sexualized at first look, educational, occupational, community, and religious situations are (Rothblum et al., 2018). Thus, how asexuality is frequently reacted to should consider this social context.

Religiosity and Attitudes Towards Sexual and Gender Minorities

Church and religious attendance are strongly associated with attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities (Jäckle & Wenzelburger, 2015; Whitehead & Perry, 2016). Legerski and Harker (2018) argue that religiosity (i.e., the degree to which one is involved with religion) significantly predicts negative attitudes towards sexual minorities and their rights. According to MacInnis and Hodson’s (2012) and Vu et al.’s (2021) research, anti-asexual attitudes were notably linked to higher degrees of religious fundamentalism. Research findings also report a positive relationship between macro-level religiosity and individual-level attitudes. On average, people oppose sexual and gender minorities’ rights more in countries with higher levels of religiosity (Dotti Sani & Quaranta, 2021). Furthermore, it is not uncommon for spiritual leaders to express their views against stigmatized groups (for example, sexual and gender minorities; Dotti Sani & Quaranta, 2021). The Greek Orthodox Church is a significant institution profoundly affecting moral issues and family values (Grigoropoulos et al., 2023, 2022a, b), while at the same time, it promotes traditional gender and family roles (Grigoropoulos, 2021a, b).

Overall, since the heteronormative model continues to be considered “core” to Greek society, attitudes towards asexual individuals offer significant insight into social stigmatization. Given that religion provides believers with a strict moral framework that involves specific attitudes towards certain social groups, attitudes towards asexuality might reflect religious proscriptions. On the other hand, opposition to asexual individuals may also be driven by conservative tendencies to maintain the status quo. To the researcher’s knowledge, there is limited research concerning the hypothesis that religious opposition to asexuality, at least in part, is driven by conservativism (i.e., tendencies to maintain the status quo by justifying it). Hence, this study is aimed at examining the effect of religiosity on attitudes towards asexual individuals and whether conservative political ideology and social norms help explain this effect.

Conservative Political Ideology

Scholars tend to define “conservatives” as those who fall between the “center” and “right” placements of the ideological scale (Araújo & Gatto, 2022). Political ideology is linked to sexual prejudice as conservatives report more opposition to sexual and gender minority individuals’ rights than liberals (Haslam & Levy, 2006; Pacilli et al., 2011). Political ideology encloses both the belief systems and the attributional processes that can actively support the justification of stigma. Thus, conservatives are more likely than liberals to accept inequality and consent to the existing social and economic inequalities (Jost & Hunyady, 2005; Jost et al., 2009). We consider these ideological variables interchangeable in this study based on previous research data reporting a significant association between political conservatism and system justification (Jost, 2017). Resistance to change is a fundamental feature of conservative political ideology (Jost et al., 2003). In addition, the association between religiosity and resistance to change is apparent since religions support traditionalism and the maintenance of the social status quo (i.e., system justification; Jost et al., 2014). Thus, taking into account that ideological self-placement on a single left–right dimension is associated with prejudice towards ostracized groups such as sexual and gender minorities (e.g., Luguri et al., 2012), this study was aimed at examining whether the endorsement of conservative ideology would mediate the effect of religiosity on attitudes towards asexual individuals.

Social Norms

In attitude-behavior models in social psychology, social norms are context-dependent, externally derived expectations of acceptable, obligatory, and appropriate behaviors shared by others in the same context or society (Bell & Cox, 2015; Cislaghi & Heise, 2018; McDonald & Crandall, 2015). Cialdini and Trost (1998, p.152) defined social norms as “rules and standards that members of a group understand and that guide or constrain social behaviors without the force of law.” In other words, what someone perceives that other people in the referent group think one should do. According to Ajzen (1991), they represent the social pressure to become involved/participate or not participate in certain behaviors. This means that social norms represent the pressure and the approval of others important to the individual (Ajzen, 1988). Specifically, descriptive and injunctive social norms highlight the relevance of significant others’ guiding behaviors. Even though they are supplementary, they represent different types of social influence guided by different psychological processes. Injunctive norms refer to the perceived attitudes or approval by others and motivate conformity by social sanctions (when deviating from the prevailing group standards) or rewards (Cialdini & Trost, 1998; Conner & Sparks, 2005). To conform to this type of influence, one does not have to agree with the opinion of others as valid. In addition, what others are perceived to do (not what others are perceived to approve of) and what is regarded as proper and foreseen in a group context is referred to as the descriptive norm (Cialdini et al., 1990). Hence, as regards the descriptive norm, the informational component might play a significant role (McDonald & Crandall, 2015).

The Current Study

With asexuality and asexual individuals becoming more visible, empirical research is necessary to address stereotypes and the prejudice and discrimination aimed at asexuals because of their opposition to society’s sexual assumption. According to Chasin (2015), the nonasexual social context considers asexual people inferior and, therefore, acts as if they do not exist. Evaluating anti-asexual prejudice positively impacts asexuals since they have frequently been overlooked in social and academic discourse (Hoffarth et al., 2015), and sexual normative arguments still declare that being sexual or nonasexual is better than being asexual (Chasin, 2015).

The current study contributes to this research by examining anti-asexuality bias in the Greek socio-cultural context that supports sexual normativity (Grigoropoulos, 2022a). More specifically, the Orthodox religion in Greece strongly affects societal attitudes and beliefs, while Greek cultural values overemphasize the importance of heteronormativity and heterosexual marriage (Voultsos et al., 2019). Most importantly, this study focuses on the Greek asexual community that has received no prior scientific attention by shedding light on an issue that is exemplary of the functions of minority pressure. The current invisibility of asexuality in academia and society emphasizes Western society’s privileging of sexual relationships over nonsexual relationships (Bulmer & Izuma, 2017; Cryle & Moore; Gupta, 2015a). However, asexuality should interest scholars in sexuality as asexual identities differ from other sexual identities and communities. The current study brings asexuality into the cultural conversation by examining context-related socio-cultural factors and norms that influence attitudes towards asexual individuals.

As Hogg and Vaughan (2005, p.150) argue, “attitudes are made of beliefs, feelings and behavioral tendencies” towards significant topics in someone’s life or community’s life. Attitudes towards asexual individuals could provide a more detailed understanding of the societal challenges asexuals may face, promote research on attitudes-based discrimination, offer ways to counteract society’s negative beliefs that may influence asexuals’ lives in different ways, and provide a better comprehension of dominant stereotypes which inform the public on specific topics. Research data illustrating the existence or inexistence of specific attitudes are necessary to accomplish the aims mentioned above.

Considering the negative consequences related to the stigmatization of asexual individuals, this study seeks to understand the perceptions and attitudes towards asexuality and to identify factors that predict an individual’s attitudes towards asexuality. Understanding predictors of asexuals’ stigmatization can disclose how sex normativity functions as a social system and lead to new strategies to avoid it. Therefore, this study examines attitudes towards asexuality, using socio-cultural (religiosity, political conservatism) and social psychological (social norms) variables as predictors.

Based on data from different cultural contexts, we expected that participants with more traditional socio-cultural traits (such as political conservatism and religiosity) would exhibit less favorable attitudes towards asexuality since it confronts sex normativity and conventional sexual and social norms (Hoffarth et al., 2015; Webb et al., 2017). Considering that anti-asexual bias signifies a subtype of sexual prejudice, similarities between anti-asexual bias and other types of sexual prejudice were expected (see MacInnis and Hodson (2012)). Thus, based on the above reasoning, this study examined the following hypothesis (H1): Political positioning and adherence to social norms will mediate the relationship between participants’ religiosity and attitudes towards asexual individuals.

As Herek (2010) argued, because nonheteronormative sexual orientations are nonnormative, they are considered imperfect and inferior. In this light, with reference to both international and Greek research data concerning sexual minorities, we hypothesized that highly religious and politically conservative individuals (Grigoropoulos, 2019, 2022b; Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015; Hoffarth et al., 2015; Grigoropoulos, 2021a, b, 2020; Iraklis et al., 2015; Pistella et al., 2017; Webb et al., 2017) would exhibit less favorable attitudes towards asexual individuals. This study also examines the relationship between participants’ attitudes towards asexual individuals and social norms concerning asexuality. Specifically, we predicted that participants’ attitudes would align with what others are perceived to do (descriptive norms) and what others are perceived to approve of (injunctive norms). This study provides insight into how a specific culture perceives asexual individuals and a better understanding of general attitudes towards asexuals. At the same time, this may help policymakers understand society’s attitudes better, adjust their practice, and educate the community on these topics. This, in turn, could reduce stigma and any possible act of discrimination.

Method

Procedure and Participants

An exploratory cross-sectional study was conducted between April 4 and May 4, 2021, via an online survey. This study is part of a larger study concerning sexual and gender minority individuals and their rights. Convenience sampling with a snowball-like technique was utilized as the URL of the questionnaire was publicized on social media accounts (e.g., LinkedIn) and posts on different social networks and also on the researcher’s university networks and forums. Participants were asked to email the study link to other possible respondents. The online survey was completely anonymous, and participants indicated their agreement to participate by selecting the consent checkbox. The inclusion criteria were (a) being at least 18 years old and (b) agreeing to participate. The survey included Johnson’s (1977, p. 99) description of asexuality to minimize the effect of disinformation gaps. The process lasted approximately 10–15 min. This study followed all principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and all the ethical instructions and directions of the institution to which the researcher belongs.

One hundred and eighty-seven participants were recruited for this study. The mean age was 20.04 (SD = 0.98). All the participants were currently undergraduate students. Participants scored low on religiosity (M = 2.86, SD = 1.22) and support to the center and center-left party (M = 2.76, SD = 0.73). No participants were excluded from the study. For detailed demographic characteristics, see Table 1.

Measures

Explanatory Variables

Socio-demographic and Attitudinal Variables

In the demographic section of the questionnaire, participants gave background information about their age (reported by participants in a numerical entry box), gender (male, female, transgender, and other-with specification required), sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, and other-with specification required), level of education (below high school, high school diploma, undergraduate student, university degree, postgraduate student, and postgraduate degree), political positioning (left party, center-left party, center party, center-right party, and right party), and religiosity (frequency of religious services attendance and frequency of praying; 1 = never to 5 = always; a single value was computed based on the average of the two items).

Injunctive and Descriptive Norms

Participants were asked to indicate on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1 = strongly disapprove to 7 = strongly approve) “What your best friends would think if you had little or no sexual attraction or desire for other people” (injunctive norms) and “If any of your friends and acquaintances have told you that has little or no sexual attraction or desire for other people” (1 = none of my friends to 7 = all of my friends; descriptive norms). Similar questions (regarding descriptive and injunctive norms) were used in Buunk and Bakker’s study (1995) concerning willingness to engage in extradyadic sexual behavior. A single value was computed based on the average of the items. Lower scores indicated greater adherence to social norms.

Outcome Measure

Attitudes Towards Asexuals (ATA)

The scale used was that by Hoffarth et al. (2015; Attitudes Towards Asexuals Scale), whose translation accuracy for the Greek context has been verified through back-translation (e.g., asexuality is a problem or defect, there is nothing wrong with not having sexual attraction, and a lot of asexual people are probably homosexual and in the closet). Participants completed 16 items on a 9-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” A single value was computed based on the average of the scales’ items. Higher scores signified more significant anti-asexual bias. Hoffarth et al. (2015) report that the ATA Scale has strong internal consistency (α = 0.94) and convergent validity with other related measures. The ATA was used based on our interest in associating religiosity and political conservatism with anti-asexual attitudes since the scale was developed to assess anti-asexual attitudes associated with religiosity and political conservatism.

Factorial Structure of the Attitudes Towards Asexual (ATA) Scale

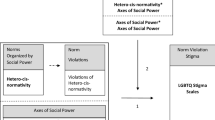

In the initial data analysis stage, the validity of the newly translated ATA scale was examined by utilizing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS-21. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted on the sixteen items of the ATA to test the measurement model. Using AMOS software, the CFA was conducted using the maximum likelihood method. Sample size recommendations of a minimum of 100 to 200 participants for CFA were met (Kline, 2005). The model-fit measures were used to assess the model’s overall goodness of fit (CMIN/df, GFI, CFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA). Initially, CFA did not demonstrate a satisfactory fit to the data: CMIN/df = 6.401, GFI = 0.669, CFI = 0.667, TLI = 0.616, SRMR = 0.173, and RMSEA = 0.0969. Inspection of the model showed that item 13 (i.e., “Υou can’t truly be in love with someone without feeling sexually attracted to them”) had a low standardized loading (< 0.30). Thus, the aforementioned item was excluded. Notably, this was the one item that did not specifically mention asexual people or even asexuality. Maybe it did not load as the other items because of the sexual inactivity-based definition of asexuality the participants were given, which might have influenced all items except for this one. Also, the Modification Indices suggested that an improved model fit could be achieved by including additional covariance paths (Fig. 1). A new CFA was computed to test the measurement model, and all values were within their respective common acceptance levels (Bentler, 1990; Hu & Bentler, 1998; Ullman, 2001). The specified one-factor model yielded a good fit (Fig. 1) for the data: CMIN/df = 2.179, GFI = 0.905, CFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.922, SRMR = 0.081, and RMSEA = 0.0569 (Table 2). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the Attitudes towards Asexuals scale was α = 0.90 (95% CI: 0.88, 0.92).

Design and Statistical Analysis

A between-subject, correlational design was employed. IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 and IBM AMOS 20 were used to analyze the data. Data screening techniques were used before the main statistical analysis. The Mahalanobis distances were used to examine outliers in the data. Six cases were deleted as outliers (see Hair et al. (1998)). The normal range for skewness and kurtosis is between + 2 and − 2 for normal distribution according to the criteria by George and Mallery (2010). That assumption was satisfied as no outliers were detected. Bivariate correlation was generated to explore the associations between variables of interest. Next, we examined our hypotheses by performing a bootstrapping analysis for parallel multiple mediation models (Hayes, 2013; Model 4). Bootstrapping bypasses power concerns in samples less than 200 (Hoyle & Kenny, 1999). Alpha level was set at 0.05.

Results

Descriptive Results

Pearson’ correlation analysis was performed between all variables of interest after the statistical assumptions were checked to examine the relationship between the research variables. The results are presented in Table 3. ATA was positively associated with political positioning (r = 0.394, p < 0.01) and religiosity (r = 0.522, p < 0.01) and negatively associated with adherence to social norms (r = − 0.453, p < 0.01). Religiosity was positively associated with political positioning (r = 0.390, p < 0.01) and negatively associated (r = − 0.247, p < 0.01) with adherence to social norms. Overall, it seems that support for right parties, higher levels of religiosity, and adherence to social norms are related to high anti-asexual bias.

Mediation Analysis

Based on our hypotheses and the pattern of bivariate correlations, we assessed the mediating role of political position and adherence to social norms on the relationship between religiosity and attitudes towards asexuals (ATA). The results revealed a significant indirect effect of religiosity on attitudes towards asexuals through political positioning, as confidence intervals did not include zero. In particular, more religious participants supported right-wing politics (α1 = 0.235) and endorsed more anti-asexual bias (b1 = 0.306). The confidence interval for the indirect effect (α1b1 = 0.072) was above 0 [0.016, 0.137]. The study also found a significant indirect effect of religiosity on attitudes towards asexuals through adherence to social norms. In particular, less religious participants were less supportive of social norms (α2 = − 0.156) and endorsed less anti-asexual bias (b2 = − 0.558). The confidence interval for the indirect effect (α2b2 = 0.078) was above 0 [0.035, 0.150], supporting this study’s hypothesis. Furthermore, the direct effect of religiosity on attitudes towards asexuals in the presence of the mediators was also significant (c′ = 0.420, p < 0.001). Hence, both political position and adherence to social norms partially mediated the relationship between religiosity and attitudes towards asexuals. Mediation summary is presented in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Research data document that asexual individuals have been subject to bias, stigmatization, and pathologization as the heteronormative societal ideal of sexual and romantic relationships maintains the highest societal status framing relationship practices and discourses on sexuality and intimacy (Aicken et al., 2013; Klesse, 2017; Ritchie & Barker, 2006). Therefore, it is most important to examine this social tabooisation and identify context-related socio-cultural and socio-psychological predictors of negative attitudes towards asexual individuals. Hence, this study examined attitudes towards asexuality in a cultural context (Greece) with limited tolerance for nonnormative sexual relationships and sexual minorities (Grigoropoulos, 2020, 2021a, b, 2022a). In particular, this study examined whether the effect of religiosity on attitudes towards asexuality would be mediated by political positioning and adherence to social norms.

The findings of this study support the role of context-related socio-cultural and social-psychological factors in determining participants’ attitudes towards asexuality. Specifically, political positioning and adherence to social norms partially mediated the association between religiosity and attitudes towards asexuality. In addition, religiosity directly influenced attitudes towards asexuality. In the present study, socio-cultural (religiosity, political positioning) and social-psychological factors (adherence to social norms) predicted participants’ anti-asexual bias. Thus, although the legitimacy of bias against asexual individuals has come under more scrutiny recently, it is still pervasive in some institutions (such as religious institutions) and ideological systems. In addition, this study’s results coincide with previous studies in this field, suggesting that attitudes towards asexuals may be negatively affected by the society-wide system of “compulsory sexuality” and the universal motivational force of sexual attraction (Conley et al., 2012; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014). Specifically, in the Western context, sexual desires, sexual activities, and sexual identifications are considered the main accepted way to love and make commitments (Conley et al., 2012). However, this perspective reinforces the stigmatization of people engaging in relationships out of “normativity’s” bounds (e.g., asexual romantic relationships). This study’s findings demonstrate that dominant conservative socio-cultural traits relate to higher anti-asexual bias. Similarities between anti-asexual bias and other types of sexual prejudice were found as expected (see MacInnis and Hodson (2012)). Thus, in this study, highly religious, politically conservative individuals conforming to society’s perceived social norms tend to report higher levels of anti-asexual bias. In this way, dominant conservative socio-cultural traits operating as a hegemonic social system devalue any nontypical, nonconventional, asexual individual. Any violation of the sexual-normativity model frames the nonconforming individual as deviant (Hoffarth et al., 2015; Webb et al., 2017). Hence, in the specific socio-cultural context of Greece, asexuals may be regarded as a threat to the dominating sexually normative culture and the conventional sexual social norms by those who come along with a narrow understanding of nontypical sexual identities.

The present study also found religiosity to be associated with more significant anti-asexual bias, echoing the findings of MacInnis and Hodson (2012) and Vu et al. (2021). In particular, religiosity is an important factor that profoundly impacts anti-asexual bias. The opposition of the Greek Orthodox Church to sexual minorities (Voultsos et al., 2019) may have significantly influenced the attitudes of highly religious participants towards sexual minority individuals. Heterosexual marriage and parenthood are strongly interrelated in Greece, and this potentially interprets the limited socio-cultural tolerance of sexual minorities (Grigoropoulos, 2022b). Unquestionably, the Greek Orthodox Church significantly affects sexuality and sexual relationship issues (Grigoropoulos, 2019; Iraklis & Kordoutis, 2015; Voultsos et al., 2021). Thus, societal recommendations of a highly religious heteronormative procreative context may also be considered as significant factors of anti-asexual bias (Grigoropoulos, 2022a, Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015). Furthermore, Greece’s highly conventional socio-cultural context emphasizes sexual and gender roles (Grigoropoulos, 2020, 2021b).

This study’s results also align with previous research underlining higher levels of political conservatism as a significant predictor of negative attitudes towards sexual minorities (Webb et al., 2017). In addition, according to this study’s results, there is a significant relationship between conforming to society’s social norms and anti-asexual bias. Thus, what participants perceived that significant people in their referent group think about asexuals significantly influenced their own attitudes towards asexuality. According to this study’s findings, the perceived negative social beliefs of participants’ referent groups about asexuals also predicted higher anti-asexual bias.

In all, participants reporting greater compliance to conventional socio-cultural norms tend to conform more to sexual normativity ideals and to oppose distinct forms of nonsexuality leading to an outgroup (people who may present stigma)-ingroup (those we identify with) status (social identity theory; Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

This study’s results identified attitude-based discrimination topics worth informing people about, such as the impact of religiosity, adherence to social norms, and political conservatism on opposition to asexuality. Providing information about the supporting base of outgroup dislike, in this case, asexual individuals, and the rationale used to oppose asexuality might be a way of promoting social change. In addition, these topics could be addressed in different types of interventions aimed at promoting insight into how a specific culture perceives asexual individuals while at the same time helping inform policymakers to understand society’s attitudes better and accordingly adjust their practice. Universities and schools are significant settings where different interventions could take place. This, in turn, could reduce stigma and any possible act of discrimination. The belief system of humanitarianism and egalitarianism, which supports the equal worth and value of all people, may also be suggested to promote beliefs and ideologies that counteract the stigma-justifying mechanisms associated with religiosity, conservative political ideology, and adherence to social norms (Crandall, 2000). Overall, understanding predictors of asexuals’ stigmatization can disclose the way sex normativity functions as a dominant social system, allowing asexual activism to challenge contemporary sexual norms and consequently lead to new strategies to avoid asexual prejudice.

Research concerning public attitudes towards asexuals is significant for challenging the controversial and taboo issue of asexuality. It would be most fruitful for future studies to examine the child-rearing practices of asexual families. This kind of research may also support adequate provision for nontypical care relationships from the law and policy perspective. This study adds to the field by assessing the possible predictors of attitudes towards asexual individuals in a cultural context (Greece) with limited tolerance for nonnormative relationships (Grigoropoulos, 2020, 2021a, 2022b). Significantly, this study also contributes to the literature in the field by providing a cross-cultural adaptation of the ATA instrument for use in another country, culture, and language. All in all, this study contributes to the literature and research in this field by reporting the transformative potential of context-related socio-cultural and socio-psychological factors that affect commonly shared attitudes towards asexuals.

Limitations

This study is not without limits. There may be a sampling bias as participants more interested in sexuality issues may have participated. This use of participants limits the general applicability of the results. Furthermore, research on the internet limits the participation of some social groups. Hence, another limitation is the homogeneity of the participants’ group, who are mostly young undergraduate women. Future studies could emphasize collecting data from a more diverse and larger sample. In addition, the scale’s single-factor structure raises the question of whether it accurately captures all attitudes towards asexuals or merely a particular subset. Also, it is unclear how Johnson’s (1977) sexual inactivity-based definition of asexuality speaks to participants’ attitudes since the ATA scale was developed with an attraction-based definition.

Conclusions

This study draws attention to the stigmatization of asexuality and also provides useful insights to understand attitudes towards asexuality in the Greek socio-cultural context. In addition, it increases the awareness of stigma towards asexual individuals. In this regard, it also warns clinical professionals, policymakers, and social agents about the current dominant sexually normative Greek socio-cultural context that may negatively affect asexuals’ lives, their relationship choices, and their families’ well-being. Stakeholders and professionals who influence people’s lives (educators, health professionals) should be aware of possible stigmatization, not further stigmatize asexual individuals making sure that they themselves do not internalize and project these stereotypical assumptions.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aicken, C. R. H., Mercer, C. H., & Cassell, J. A. (2013). Who reports absence of sexual attraction in Britain? Evidence from national probability surveys. Psychology and Sexuality, 4, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774161

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Dorsey Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Araújo, V., & Gatto, M. A. C. (2022). Can conservatism make women more vulnerable to violence? Comparative Political Studies, 55(1), 122–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140211024313

Aven. (2021). About asexuality [Online]. [Accessed on 5–2–2021]. Available at: https://www.asexuality.org/?q=overview.html

Bell, D. C., & Cox, M. L. (2015). Social norms: Do we love norms too much? Journal of family theory & review, 7(1), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12059

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bogaert, A. F. (2004). Asexuality: Prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample. Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552235

Bogaert, A. F. (2012). Understanding asexuality. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefiel.

Bogaert, A. F. (2015). Asexuality: What it is and why it matters. Journal of Sex Research, 52(4), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1015713

Brotto, L. A., Knudson, G., Inskip, J., Rhodes, K., & Erskine, Y. (2010). Asexuality: A mixed-methods approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x

Brotto, L. A., & Yule, M. A. (2011). Physiological and subjective sexual arousal in self-identified asexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(4), 699–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9671-7

Brotto, L. A., Yule, M. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). Asexuality: An extreme variant of sexual desire disorder? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 646–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12806

Brunning, L., & McKeever, N. (2020). Asexuality. Journal of Applied Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12472

Bulmer, M., & Izuma, K. (2017). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward sex and romance in asexuals. The Journal of Sex Research, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1303438

Buunk, B. P., & Bakker, A. B. (1995). Extradyadic sex: The role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Journal of Sex Research, 32(4), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499509551804

Carrigan, M. (2011). There’s more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community. Sexualities, 14, 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711406462

Carrigan, M., Gupta, K., & Morrison, T. G. (2013). Asexuality special theme issue editorial. Psychology and Sexuality, 4(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774160

Cerankowski, K. J., & Milks, M. (2010). New orientations: Asexuality and its implications for theory and practice. Feminist Studies, 36(3), 650–665.

Chasin, C. D. (2011). Theoretical issues in the study of asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9757-x

Chasin, C. D. (2013). Reconsidering asexuality and its radical potential. Feminist Studies, 39(2), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2013.0054

Chasin, C. D. (2015). Making sense in and of the asexual community: Navigating relationships and identities in a context of resistance. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2203

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026.

Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2018). Four avenues of normative influence: A research agenda for health promotion in low and mid-income countries. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 37(6), 562–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000618

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Valentine, B. (2012). A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868312467087

Conner, M., & Sparks, P. (2005). The theory of planned behavior and health behaviors, in M. Conner and P. Norman (eds) Predicting health behavior (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Crandall, C. S. (2000). Ideology and lay theories of stigma: The justification of stigmatization. In T. F. Heatherton (Ed.), The social psychology of stigma (pp. 126–150). Guilford Press.

Dawson, M., McDonnell, L., & Scott, S. (2016). Negotiating the boundaries of intimacy: The personal lives of asexual people. Sociological Review, 64, 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12362

Decker, J. S. (2015). The invisible orientation: An introduction to asexuality. Skyhorse.

Deutsch, T. (2018). Asexual people’s experience with microaggressions. John Jay College of Criminal Justice: Student Theses, Retrieved from: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1050&context=jj_etds

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Quaranta, M. (2021). Mapping changes in attitudes towards gays and lesbians in Europe: An application of diffusion theory. European Sociological Review, 38(1), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab032

Emens, E. F. (2014). Compulsory sexuality. Stanford Law Review, 66, 303.

George, D. & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference 17.0 Update. 10th Edition, Pearson, Boston.

Ginoza, M. K., Miller, T., and AVEN, Survey Team (2014). The 2014 AVEN Community Census: Preliminary Findings (pp. 1–19).

Greaves, L. M., Barlow, F. K., Huang, Y., Stronge, S., Fraser, G., & Sibley, C. G. (2017). Asexual identity in a New Zealand national sample: Demographics, well-being and health. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 46, 2417–2427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0977-6

Gressgård, R. (2013). Asexuality: From pathology to identity and beyond. Psychology and Sexuality, 4(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774166

Grigoropoulos, I. (2019). Attitudes toward same‑sex marriage in a Greek sample. Sexuality &Culture, 23, 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9565-8

Grigoropoulos, I. (2020). Subtle forms of prejudice in Greek day-care centres. Early childhood educators’ attitudes towards same-sex marriage and children’s adjustment in same-sex families. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(5), 711–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1835636

Grigoropoulos, I. (2021a). Lesbian motherhood desires and challenges due to minority stress. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02376-1

Grigoropoulos, I. (2021b). Lesbian mothers’ perceptions and experiences of their school involvement. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2537

Grigoropoulos, I. (2022a). Towards a greater integration of ‘spicier’ sexuality into mainstream society? Social-psychological and socio-cultural predictors of attitudes towards BDSM. Sexuality & Culture. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-09996-0

Grigoropoulos, I. (2022b). Greek high school teachers’ homonegative attitudes towards same-sex parent families. Sexuality & Culture. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09935-5

Grigoropoulos, I., Daoultzis, K. C., & Kordoutis, P. (2023). Identifying context-related socio-cultural predictors of negative attitudes toward polyamory. Sexuality & Culture, 27, 1264–1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10062-6

Grigoropoulos, I., & Kordoutis, P. (2015). Social factors affecting antitransgender sentiment in a sample of Greek undergraduate students. International Journal of Sexual Health, 27(3), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2014.974792

Gupta, K. (2015a). What does asexuality teach us about sexual disinterest? Recommendations for health professionals based on a qualitative study with asexually identified people. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1113593

Gupta, K. (2015b). Compulsory sexuality: Evaluating an emerging concept. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 41(1), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1086/681774

Gupta, K. (2017). “And now I’m just different, but there’s nothing actually wrong with me”: Asexual marginalization and resistance. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(8), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1236590

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R. and Black, W. (1998) Multivariate data analysis. 5th Edition, Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (Seven ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ Prentice Hall: Pearson.

Haslam, N., & Levy, S. R. (2006). Essentialist beliefs about homosexuality: Structure and implications for prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(4), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205276516

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Bellatorre, A., Lee, Y., Finch, B. K., Muennig, P., & Fiscella, K. (2014). Structural stigma and all-cause mortality in sexual minority populations. Social Science & Medicine, 1982(103), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.005

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Herek, G. M. (2010). Sexual orientation differences as deficits: Science and stigma in the history of American psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 693–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610388770

Hinderliter, A. C. (2009). Methodological issues for studying asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(5), 619–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9502-x

Hoffarth, M. R., Drolet, C. E., Hodson, G., & Hafer, C. L. (2015). Development and validation of the attitudes towards asexuals (ATA) scale. Psychology & Sexuality, 7(2), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2015.1050446

Hogg, M., & Vaughan, G. (2005). Social Psychology (4th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Hoyle, R. H., & Kenny, D. A. (1999). Statistical power and tests of mediation. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Statistical strategies for small sample research. Newbury Park: Sage

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Iraklis, G., & Kordoutis, P. (2015). Reliability and validity of the Greek translation of the same-sex marriage scale. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12(4), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428x.2015.108013

Jäckle, S., & Wenzelburger, G. (2015). Religion, religiosity, and the attitudes toward homosexuality—a multilevel analysis of 79 countries. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(2), 207–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.969071

Johnson, M. T. (1977). Asexual and auto-erotic women: Two invisible groups. In H. L. Gochros & J. S. Gochros (Eds.), The sexually oppressed (pp. 96–109). Associated Press.

Jones, C., Hayter, M., & Jomeen, J. (2017). Understanding asexual identity as a means to facilitate culturally competent care: A systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 3811–3831. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13862

Jost, J. T. (2017). Ideological asymmetries and the essence of political psychology. Political Psychology, 38, 167–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12407

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

Jost, J. T., Hawkins, C. B., Nosek, B. A., Hennes, E. P., Stern, C., Gosling, S. D., & Graham, J. (2014). Belief in a just God (and a just society): A system justification perspective on religious ideology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 34(1), 56–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033220

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of system-justifying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(5), 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00377.x

Jost, J. T., Krochik, M., Gaucher, D., & Hennes, E. P. (2009). Can a psychological theory of ideological differences explain contextual variability in the contents of political attitudes? Psychological Inquiry, 20(2–3), 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400903088908

Kelleher, S., & Murphy, M. (2022). Asexual identity development and internalisation: a thematic analysis. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2022.2091127

Kelleher, S., Murphy, M., & Su, X. (2023). Asexual identity development and internalisation: A scoping review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychology & Sexuality, 14(1), 45–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2022.2057867

Kim, E. (2010). How much sex is healthy? The pleasures of asexuality. In J. Metzl & A. Kirkland (Eds.), Against health: How health became the new morality (pp. 157–169). New York University Press.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Saunders.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Klesse, C. (2017). Theorizing multi-partner relationships and sexualities – Recent work on non-monogamy and polyamory. Sexualities, 21(7), 1109–1124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717701691

Legerski, E., & Harker, A. (2018). The intersection of gender, sexuality, and religion in Mormon mixed-sexuality marriages. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 78(7–8), 482–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0817-0

Luguri, J. B., Napier, J. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2012). Reconstruing intolerance: Abstract thinking reduces conservatives’ prejudice against nonnormative groups. Psychological Science, 23(7), 756–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611433877

MacInnis, C. C., & Hodson, G. (2012). Intergroup bias toward “Group X”: Evidence of prejudice, dehumanization, avoidance, and discrimination against asexuals. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15, 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212442419

MacNeela, P., & Murphy, A. (2014). Freedom, invisibility, and community: A qualitative study of self-identification with asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0458-0

McDonald, R. I., & Crandall, C. S. (2015). Social norms and social influence. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.04.006

Pacilli, M. G., Taurino, A., Jost, J. T., & van der Toorn, J. (2011). System justification, right-wing conservatism, and internalized homophobia: Gay and lesbian attitudes toward same-sex parenting in Italy. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 65(7–8), 580–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9969-5

Pistella, J., Tanzilli, A., Ioverno, S., Lingiardi, V., & Baiocco, R. (2017). Sexism and attitudes toward same-sex parenting in a sample of heterosexual and sexual minorities: The mediation effect of sexual stigma. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0284-y

Prause, N., & Graham, C. A. (2007). Asexuality: Classification and characterization. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9142-3

Przybylo, E. (2011). Crisis and safety: The asexual in sexusociety. Sexualities, 14(4), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711406461

Ritchie, A., & Barker, M. (2006). ‘There aren’t words for what we do or how we feel so we have to make them up’: Constructing polyamorous languages in a culture of compulsory monogamy. Sexualities, 9, 584–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460706069987

Robbins, N. K., Low, K. G., & Query, A. N. (2015, September 3). A qualitative exploration of the “coming out” process for asexual individuals. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 45(3), 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0561-x

Rothblum, E. D., & Brehony, K. A. (1993). Boston marriages: Romantic but asexual relationships among contemporary lesbians. University of Massachusetts Press.

Rothblum, E. D., Heimann, K., & Carpenter, K. (2018). The lives of asexual individuals outside of sexual and romantic relationships: Education, occupation, religion and community. Psychology & Sexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1552186

Scherrer, K. S. (2008). Coming to an asexual identity: Negotiating identity, negotiating desire. Sexualities, 11(5), 621–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460708094269

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

Ullman, J. B. (2001). Structural equation modeling. In: B. G. Tabachnick, & L. S. Fidell (Eds.), Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Van Houdenhove, E., Enzlin, P., & Gijs, L. (2017). A positive approach toward asexuality: Some first steps, but still a long way to go. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 46, 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0921-1

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T’Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2013). Asexuality: Few facts, many questions. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(3), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2012.751073

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T'Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2015). Asexuality: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Sex Research, 52(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.898015

Voultsos, P., Zymvragou, C. E., Raikos, N., & Spiliopoulou, C. C. (2019). Lesbians’ experiences and attitudes towards parenthood in Greece. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1442021

Voultsos, P., Zymvragou, C. E., Karakasi, M. V., & Pavlidis, P. (2021, February 18). A qualitative study examining transgender people’s attitudes towards having a child to whom they are genetically related and pursuing fertility treatments in Greece. BMC Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10422-7

Vu, K., Riggs, D. W., & Due, C. (2021). Exploring anti-asexual bias in a sample of Australian undergraduate psychology students. Psychology & Sexuality, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1956574

Webb, S. N., Chonody, J. M., & Kavanagh, P. S. (2017). Attitudes toward same-sex parenting: An effect of gender. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(11), 1583–1595. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1247540

Whitehead, A. L., & Perry, S. L. (2016). Religion and support for adoption by same-sex couples: The relative effects of religious tradition, practices, and beliefs. Journal of Family Issues, 37(6), 789–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14536564

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2013). Mental health and interpersonal functioning in self-identified asexual men and women. Psychology and Sexuality, 4, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774162

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2017). Human asexuality: What do we know about a lack of sexual attraction? Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0100-y

Zheng, L., & Su, Y. (2018). Patterns of asexuality in China: Sexual activity, sexual and romantic attraction, and sexual desire. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1265–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1158-y

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. The authors have no funding to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iraklis, G. Examining the Social Tabooisation of Asexuality: The Underpinnings of Anti-Asexual Bias. Sex Res Soc Policy (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00884-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00884-2