Abstract

Introduction

How we perceive social-sexual behavior, and to what extent we consider such behavior to be sexual harassment, is dependent on several situational factors. Prototypical #MeToo features (male actor and female target, higher status, repeated, private behavior, sexualized physical contact) have previously been shown to increase the degree to which social-sexual behavior is perceived as sexual harassment. The effect of those features needs to be investigated for types of harassment that involve same-gender sexual harassment and harassment of LGBTQ + people. To gain a wider perspective on the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment, this preregistered study aims to examine same-gender interactions and lesbian and gay actors and targets, in addition to replicating earlier findings about #MeToo features in opposite-sex constellations.

Methods

We applied five hypothetical scenarios to a Norwegian online sample of 888 participants between 18 and 60 (58.3% cis women, 40.8% cis men, 0.9% transgender/genderfluid/non-binary). The sampling process took place during the spring term 2020 and aimed at recruiting LGBTQ + people (63.3% of the sample self-identifying as heterosexual, 20% gay/lesbian, 10.7% bisexual, 3.2% pansexual, and 1.9% “other”).

Results

#MeToo features in each scenario clearly increased the degree to which social-sexual behavior was perceived as sexual harassment across gender identity and sexual orientation. The effect of private vs. public behavior was contingent on the type of behavior. Men rated behavior less as sexual harassment than women and people of other gender identities.

Conclusions

The current study shows that there was considerable consensus as to what sexual harassment entails in the five scenarios across gender identity and sexual orientation.

Policy Implications

Organizations should include prototypical #MeToo features in interventions, to illustrate how a situation might be more or less undesired and therefore experienced as harassment under different circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To reduce workplace sexual harassment, there is a need to ascertain what kinds of behaviors are commonly agreed upon as constituting sexual harassment. In other words: what features of social-sexual behaviors result in people perceiving the behavior as sexual harassment. While the term has no universally used definition, sexual harassment is often defined as “unwanted sexual attention” (McMaster et al., 2002; Norwegian Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act, 2017) or “unwelcomed sexual advances” (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1980). As most definitions include the subjective perception of the person targeted, there are no certain behaviors that are defined as sexual harassment while others are not. Therefore, it is important to study whether people have a general idea of what kind of social-sexual behavior (social behavior with a sexual dimension; Rotundo et al., 2001) they would perceive as sexual harassment. Moreover, the perceptions of observers or third parties are essential, as they may influence the work environment and the degree of support targets may receive. Perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment seems to be influenced by both situational features and personality traits (Golden et al., 2001; Kessler et al., 2020; Rotundo et al., 2001). In criminal cases, we often rely on what is called a “reasonable person standard,” meaning that the question of culpability is discussed with reference to how a “reasonable person” would have behaved in similar circumstances (Alicke & Weigel, 2021). How people of different genders or sexual orientation perceive and categorize sexual harassment is therefore not only important in the workplace; it may be important for allegations brought to the judicial system as well.

Sexual harassment has gained worldwide attention due to the #MeToo movement (Ennis & Wolfe, 2018), as thousands of people shared their personal experiences with sexual harassment, assault, and sexism online, using the hashtag #MeToo (CBS, 2017). The #MeToo movement caused a surge of interest in harassment (Caputi et al., 2019) and made sexual harassment and organizational policies more visible (Alvinius & Holmberg, 2019). However, the #MeToo movement has also been criticized. For one, in the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, men in the UK reported to be afraid to mentor women (Sandberg & Pritchard, 2019), and 43% of working men in the USA reported to be afraid of being wrongly accused and were therefore more likely to exclude women from social interactions (Atwater et al., 2021). Thus, there is reason to worry about gender diversity in the workplace. Moreover, the #MeToo movement has been criticized for its focus on white, heterosexual cis women, excluding groups such as women of color and LGBTQ + people (Hemmings, 2018; Onwuachi-Willig, 2018; Zarkov & Davis, 2018). Finally, most famous cases that were reported on and discussed displayed a prototypical type of sexual harassment. An overview over 262 cases of sexual harassment showed that most cases shared several situational features (see Appendix B for full list). These features were male actor and a female target, superior status of the actor, repeated over single case behaviors, personal over public comments, and sexualized physical contact, which have been previously defined as prototypical #MeToo features (Kessler et al., 2020). More prototypical phenomena are more likely to be identified as part of a specific category (Rosch, 1999), and it may be that prototypical #MeToo features would increase the likelihood of an ambiguous social-sexual behavior being perceived as sexual harassment.

Non-prototypical sexual harassment was clearly under covered by the #MeToo movement. This includes same-gender sexual harassment, which has been shown to be highly prevalent among high school students (Bendixen & Kennair, 2017; Fineran, 2002), as well as harassment of men by other men in the workplace (Nielsen et al., 2010). Furthermore, the victimization of LGBTQ + people has received little attention in the #MeToo movement, and more research of sexual harassment perception of these groups is highly warranted. To broaden the current heteronormative view of sexual harassment, this study examines both opposite- and same-gender harassment, including how LGBTQ + behavior and victimization are perceived by heterosexual and LGBTQ + participants.

To our knowledge, there are to date no studies examining the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment that include LGBTQ + people. People may perceive social-sexual behavior more as sexual harassment when the target is identifying as being part of the LGBTQ + community, as this group is generally subjected to sexual harassment and discrimination to a larger degree (Kosciw et al., 2013; Zurbrügg & Miner, 2016). How people might react to scenarios in which LGBTQ + people are targeting others, or both actor and target are part of the LGBTQ + community, remains to be examined.

Moreover, how one’s own sexual orientation influences perception is not clear. Women and men seem to differ in their perception of sexual harassment, as women are more likely to rate social-sexual behaviors as being sexual harassment than men are (Kessler et al., 2020; Rotundo et al., 2001). It is possible that heterosexual and LGBTQ + people also differ in their perception, either due to being more sensitized to same-gender social-sexual behavior or because they are more likely to be subjected to sexual harassment themselves. Including the perspectives of LGBTQ + people will add an important perspective to sexual harassment research.

Prototypical #MeToo Features

During the #MeToo movement, many sexual harassment cases were made public. A post hoc consideration (see Appendix B) of 262 cases listed by vox.com (North et al., 2020) showed features that were shared by most cases. The most prominent shared feature was the actor holding more power than the target, occurring in 93% of cases. The most prevalent gender constellation was a male actor and a female target, occurring in 90% of cases. Around 84% of the cases showed repeated behavior. Within this list, there was merely a distinction between isolated cases, and a pattern of behavior, independent of whether the actor subjected multiple people or subjected one person repeatedly. Thirty percent of cases showed quid pro quo behavior, which is considerably lower than the other features detected. However, 50% of the ten most reported cases (determined through most google searches) have shown quid pro quo behavior, and it has been depicted in the Harvey Weinstein case, the most notorious and mentioned case. Eighty-seven percent of cases depicted cases of workplace sexual harassment. Situations such as after-work parties or private “auditions” were categorized as workplace situations. Sixty-two percent of cases depicted private behavior, rather than public, though 12% of cases depicted behavior occurring both in private and in public. Finally, 78% percent of cases involved some form of physical harassment. Based on the post hoc consideration of these cases, the following features can be defined as prototypical #MeToo features: male actor and female target, sexualized physical contact, private behavior, repeated behavior, and a higher status actor, all raised the probability of social-sexual behavior to be rated as sexual harassment (Kessler et al., 2020). Before the #MeToo movement gained attention in 2017, it had already been shown that certain situational features increased the likelihood of people perceiving social-sexual behaviors as sexual harassment, for example, a position of power of the actor (Bursik & Gefter, 2011; Gordon et al., 2005; Rotundo et al., 2001).

Gender of Actor and Target

Studies have shown that people are more likely to perceive social-sexual behavior as being sexual harassment when it portrays a male actor and a female target (Bitton & Shaul, 2013; Gutek et al., 1983; Hendrix et al., 1998; McCabe & Hardman, 2005; Runtz & O'Donnell, 2003). This could be due to more women being subjected to sexual violence, assault, or rape, or to the fact that men are, on average, physically stronger than women and may therefore be perceived more as a possible threat than women are (Larsen, 2003; Rudman & Goodwin, 2004). This could also stem from stereotypical beliefs that men are more sexual and therefore would welcome any type of sexual attention, while women are coyer and therefore do not welcome sexual attention to the same degree as men.

In this study, we aim to expand on the different gender constellations.Footnote 1 Men are subjected to some forms of non-physical sexual harassment in the workplace to the same extent as women, such as “unwanted comments about one’s body, clothing, or way of living” (Nielsen et al., 2010). Furthermore, same-gender sexual harassment has shown to be highly prevalent among Norwegian youth, with slut-shaming being highly prevalent among girls, and homonegative comments being highly prevalent among boys (Bendixen & Kennair, 2017). Sexual harassment does not only happen between different genders, but also happen between individuals of the same gender. However, only a few studies have examined same-gender behaviors (e.g., Bendixen & Kennair, 2017; Kennair & Bendixen, 2012). Bitton and Shaul (2013) conducted a study in Israel that found that same-gender behavior among females was least likely to be perceived as harassment by both women and men, and that women were more likely to perceive behavior that targeted males as sexual harassment. There were no gender differences when perceiving male actors and female targets, or female actors and female targets (Bitton & Shaul, 2013). How same- and opposite-gender behavior will influence perception of social-sexual behaviors in a more gender egalitarian nation such as Norway, how members of the LGBTQ + community will perceive these, and how additional, prototypical features influence perceptions remain to be examined.

Workplace Status

When considering workplace sexual harassment specifically, workplace status is an especially important situational factor. Social-sexual behavior from an actor higher in workplace status than the target may lead to negative consequences for the target’s career due to their reactions or lack thereof. How one would react to sexual advances made by someone higher in status could be influenced by hopes of a promotion or better working conditions, or by the fear of termination or a worsening of working conditions. Studies have shown that social-sexual behavior is more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment when the actor is of higher status than the target, even before the #MeToo movement (Bursik & Gefter, 2011; Gordon et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2020; Rotundo et al., 2001).

Repeated Behavior

Many well-known #MeToo cases have involved repeat offenders. Repeated social-sexual behavior is a well-established feature enhancing the probability of rating such behavior as sexual harassment (Ellis et al., 1991; Hurt et al., 1999; Kath et al., 2014; Kessler et al., 2020). However, how repeated behavior is perceived by LGBTQ + participants, or how repeated same-gender social-sexual behavior is perceived, has not been established.

Private over Public Settings

Social-sexual behaviors occurring in private settings of the workplace, for instance, in a private office without colleagues being present, are more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment, than the same behavior being displayed in public (Kessler et al., 2020). It is possible that a private setting is perceived as more threatening or harassing, because of the lack of possible support or interference from colleagues, as well as the absence of witnesses. However, so far only the perception of opposite-gender harassment has been studied, leaving out same-gender harassment. This remains to be examined.

Sexualized Physical Contact

When sexualized physical contact, such as touching of the face, waist, buttocks, chest, or genitals, occurs, social-sexual behavior is more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment, compared to social-sexual behavior including physical contact that is not sexualized, such as patting someone’s shoulder or shaking someone’s hand (Kessler et al., 2020; Lee & Guerrero, 2001; Rotundo et al., 2001).

Current Study: Aims and Hypotheses

The probability of social-sexual behavior to be perceived as sexual harassment is higher when prototypical #MeToo features are present in a situation (Kessler et al., 2020). The aim of this preregistered study is to replicate earlier findings concerning the influence of prototypical #MeToo features on the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment (Kessler et al., 2020). Furthermore, we aim to expand our previous study by examining same-gender sexual harassment scenarios as well as including the perspective of LGBTQ + people and people with gender identities other than cis female and cis male. There are currently no studies examining same-gender sexual harassment perception among that group.

Hypotheses, Predictions, and Explorative Research Questions

The following hypotheses were preregistered at Open Science (https://osf.io/xc873/),Footnote 2 and will be subject to testing:

H1: Women will evaluate social-sexual behaviors more as sexual harassment than men do (Kessler et al., 2020; Rotundo et al., 2001).Footnote 3

H1.1: Men will evaluate social-sexual behaviors less as sexual harassment than women do if the actor is female and the target is male (Kessler et al., 2020).

H2: Social-sexual behavior will be perceived more as sexual harassment if it contains prototypical #MeToo features; male over female actor, superior over subordinate actor, repeated over single case harassment, private over public settings, and sexualized physical contact over non-sexualized physical contact (Kessler et al., 2020).

In addition, we aim to explore the following research questions:

RQ1: How will both heterosexual and LGBTQ + participants perceive same-gender social-sexual behavior? Same-gender harassment has rarely been studied and it is therefore not clear whether it will be perceived less as sexual harassment, as media has had a more heteronormative perspective (such as a male actor and a female target), or if especially LGBTQ + participants will perceive such behavior more as harassment, as they might be more aware of this type of behavior.

RQ2: How will the sexual orientation of the actor influence the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment? E.g., will LGBTQ + participants differ from straight participants in their perception of same-gender and opposite-gender social-sexual behavior, and particularly so if target and/or actor is part of the LGBTQ + group?

RQ3: To what extent will people perceive the hypothetical scenarios as prevalent and realistic?

RQ4: Will people’s rating of scenarios as realistic and common influence their perception of those scenarios as sexual harassment?

When introducing gender constellations that divert from the stereotypical female target and male actor constellation and adding new populations to the scenarios that have not previously been studied, measuring realism and commonality of the scenarios ensures the relevance and possible familiarity, and may increase the trustworthiness and validity of the findings.

This study is in part a replication of an earlier study (Kessler et al., 2020), aiming to increase validity of earlier findings, while also expanding on gender constellations and new types of social-sexual behavior (scenarios), and including a LGBTQ + perspective.

Methods

Design and Participants

In total, 943 people completed an online questionnaire. Each participant responded to one of four versions of the questionnaire that differed only with regard to the actor-target gender constellation (woman-man, man-woman, woman-woman, and man-man). A randomization procedure allocated each respondent to one of the four questionnaire versions. Those who did not report their age (n = 13) or who reported being younger than 18 (n = 1) were excluded from the analysis for ethical reasons. Because of low representativity, and to be able to replicate earlier findings with the same age range, we also removed respondents older than 60 years (n = 41).Footnote 4 Screening procedures were applied to identify high degree of anomality or monotonous responding, but those did not lead to further exclusions. The final sample eligible for analyses consisted of 888 participants aged between 18 and 60 years (M = 33.48, SD = 12.11). We posed separate questions on sex at birth and gender identity. For 95.2% of the sample, the gender identity matched their sex at birth. Of these, 503 (56.7%) were cis women and 342 were cis men (38.5%). Of the remaining 43 (4.8%) participants, 13 were transgender and nine identified as both woman and man, five as neither woman nor man, and 10 as non-binary (an additional four did not report on their sex at birth, only on their gender identity). Due to low case numbers, these groups were collapsed into one group, referred to as transgender/genderfluid/non-binary throughout the paper.

When asked about their sexual orientation, 63.3% of the sample self-identified as heterosexual, 20.9% as gay/lesbian, 10.7% as bisexual, and 3.2% as pansexual, and 1.9% chose the option “other.” We collapsed the four latter groups into one single group, referred to as LGBP + throughout the paper, due to a priori power analysis and group size demands. Of the sample, 59.4% reported to be currently working, and 82.4% had at least 1 year of working experience.

Procedure

A link to the survey was shared via Facebook and other social platforms and included information on the study. The link was shared by the authors of this paper, as well as a group of Bachelor students who were part of the process of evaluating scenarios, with the instruction to share the link further. Participation was both voluntary and anonymous (no personal identifiers were recorded). We contacted several LGBTQ + interest groups in Norway to increase recruitment specifically from the LGBTQ + community. Among these were Gaysir, a Norwegian online platform for LGBTQ + people. They posted a link to the study on their homepage and their Facebook page for 2 weeks. Participants were encouraged to share the link on social platforms.

Measurements

The novel aspect of this study is the introduction of same-gender interactions in addition to the interactions between women and men as actors and targets. As in our previous data collection, all scenarios take place in a work environment. When responding, each participant considered one of four possible gender constellations: female actor and female target, female actor and male target, male actor and female target, or male actor and male target (i.e., four versions of the questionnaire) using a randomization procedure (random allocation to questionnaire version). Before being presented with the scenarios, participants were given the definition of sexual harassment; “Sexual harassment means any form of unwanted sexual attention that has the purpose or effect of being offensive, intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or bothersome” (Norwegian Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act, 2017).

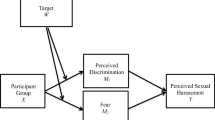

Five hypothetical scenarios were used to measure the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment. Two of these were identical to those applied in a previous study (Kessler et al., 2020). The first scenario describes an invitation to a date (Date); the second describes a hug that “lasts a little too long” between colleagues as a congratulatory gesture (Hug). Three new scenarios were developed to measure perception of sexual harassment: a homonegative comment, a degrading comment on sexual low standards (i.e., regarding sexual partners) (Comment low standards), and an objectifying comment on one’s body. The specific instructions read: “In the following we present five scenarios describing two persons involved in behaviors that may be sexually harassing. First, we ask you to assess these behaviors on a general basis, and second, provide new assessments when additional information is provided about the involved parties and their behaviors.” For each scenario, the participants rated their perception of to what degree the social-sexual behavior was sexual harassment on a 6-point Likert scale with anchors ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 6 (Absolutely!). After the initial rating (baseline rating), participants were asked how realistic they perceive this scenario to be, and how common they feel the depicted situation is on a scale with anchors 1 (Not at all) and 6 (Absolutely!). Following each scenario and their initial response, participants were subsequently asked to provide new ratings of their perception of to what degree the social-sexual behavior was sexual harassment given additional situational features. These additional features included differences in workplace status between actor and target, repeated vs. single case behavior, behavior in a public vs. private setting, inclusion of sexualized physical contact vs. non-sexualized physical contact, and finally, what if the actor, target, or both were described as gay or lesbian. However, sexualized physical contact or that both the actor and target were described as gay or lesbian was only added to those scenarios where it seemed appropriate, as it did not feel realistic to add, e.g., physical contact to a shaming comment. See Appendix A for details on wording and additional information provided for each scenario.

Analysis

For measuring perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment, we applied a 3 (gender of actor: woman vs. man vs. transgender/genderfluid/non-binary) by 2 (gender constellation: same-gender vs. opposite-gender) factorial design.

A priori power analysis: Prior studies (Kessler et al., 2020; Rotundo et al., 2001) have reported small-to-medium gender effect sizes for perception of social-sexual behavior (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.30). Given alpha probability of error of 0.05 and power of 0.95, the estimated total number of participants needed for identifying an effect of this magnitude is n = 934 with a three-group factorial design (participant gender, 4 gender constellations, 3 sexual orientation groups). This suggests a minimum of 40 participants for each of the 24 groups.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Results

Baseline and Gender Differences

To test the first hypotheses concerning gender differences and prototypical #MeToo features, we performed a mixed model ANOVA with the five scenarios as the within-subject factor, and participant gender (cis women vs. cis men vs. transgender/genderfluid/non-binary), actor gender (female vs. male), gender constellation (same-gender vs. opposite-gender), and participant sexual orientation (hetero vs. LGBP +) as between-subject factors. Effects with observed power under 0.80 are omitted. For all within main effects and interactions with within effects, we reported Wilk’s lambda. Estimated marginal means (MM) are reported.

We found a significant gender difference in baseline perception across the five scenarios (F(2,842) = 20.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.047, power = 1) (see Fig. 1). A Bonferroni post hoc test showed women (MM = 2.67) did not differ from other gender identities (MM = 2.79) in their overall ratings (p = 0.650), while both women (p < 0.001) and other gender identities (p = 0.001) rated the five behaviors significantly more as harassment than men did (MM = 2.23).

The extent to which the five scenarios were perceived as sexual harassment differed markedly (F(4,839) = 83.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.286, power = 1). When comparing all five scenarios, and as shown in Fig. 1, invitation to a date was rated least as sexual harassment (M = 1.56), while the objectifying comment was perceived most as sexual harassment (M = 3.51).

Sexual orientation did neither have an effect on levels of perception (F(1,842) = 1.73, p = 0.188) nor have an effect on the profile of scenarios (F(4,839) = 0.63, p = 0.641). Gender of actor did show a small but significant effect (F(1,842) = 7.44, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.009) (higher ratings for male actors). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between gender of actor and scenarios (F(4,839) = 8.86, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.041, power = 0.999). Finally, we found a significant effect for gender constellation. Opposite-gender behavior was rated more as sexual harassment than same-gender behavior (F(1,842) = 13.39, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.016, power = 0.955). Furthermore, gender constellation interacted significantly with scenarios (F(4,839) = 6.70, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.031, power = 0.993).

The more specific Hypothesis H1.1 predicted that men would evaluate social-sexual behavior less as sexual harassment than women do if the actor is female and the target is male. To test this, we repeated the above analysis for the subsample of men and women reporting perception of opposite-gender constellations and female actors only (n = 224). Overall, controlling for sexual orientation, men perceived the scenarios moderately less as sexual harassment than women (F(1,220) = 18.49, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.078).

Prototypical #MeToo Features

In analyzing the situational features and their influence on the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment, we calculated difference scores for all additional features (i.e., additional feature score − baseline score).Footnote 5 A positive score denotes that behavior including this feature is perceived more as sexual harassment relative to baseline. We then performed a mixed model ANOVA with the situational feature as the within-subject factor, and, as above, participant gender (cis woman vs. cis man vs. transgender/genderfluid/non-binary), harasser gender (female vs. male), gender constellation (same-gender vs. opposite-gender), and participant sexual orientation (hetero vs. LGBP +) as between-subject factors. We included all scenarios in the analysis to test the situational features for the scenarios as a whole (as will be seen in several figures). For significant feature × scenario interaction effects, we also analyzed each scenario individually. We report Wilk’s lambda F-values, eta squared, power, and estimated marginal means (MM) throughout.

Private vs. Public

We did find a significant effect for behavior happening in a private vs. in public places (F(1,806) = 10.75, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.013, power = 0.906). This main effect was significantly different for the five scenarios (F(4,803) = 36.98, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.156, power = 1). As seen in Fig. 2, scenario 2 (Hug) was the only scenario that was more likely to be perceived as harassment when it took place in a private setting than in public, whereas all other scenarios were more likely to be perceived as harassment when taking place in public. The individual analysis of each scenario showed that the effect of setting was small, but significant for the Date (ηp2 = 0.009) and the Objectifying comment (ηp2 = 0.008) scenarios. For Homonegative comments (ηp2 = 0.062) and Comments on low standards (ηp2 = 0.043), the setting effect was medium in the direction of being perceived more as sexual harassment when the setting was public. In contrast, the Hug scenario was perceived moderately more as sexual harassment when it took place in a private setting as opposed to a hug in public (ηp2 = 0.078).

Workplace Status Differentials

We found a significant and large effect of actor status on the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment (F(2,822) = 177.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.302, power = 1) (see Fig. 3). Behavior of an actor with higher status than the target was perceived markedly more as sexual harassment than behavior of an actor of equal or lower status. The effect of actor status was moderated by participant gender (F(4,1646) = 2.92, p = 0.020, ηp2 = 0.007) and by type of scenario (F(8,816) = 12.96, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.113, power = 1).

Further examination of the effect of actor status for each scenario in separate analyses showed that the effect was strongest for scenarios 1 and 5 (both large effects: ηp2 = 0.131), followed by scenario 2 (ηp2 = 0.128), scenario 3 (ηp2 = 0.094), and scenario 4 (ηp2 = 0.081). Hence, the effect of the actor having a higher status was stronger for scenarios describing a date, a hug, and an objectifying comment.

Repeated Behavior

Overall, participants viewed social-sexual behavior more as sexual harassment when the behavior was repeated in contrast to being a one-time occurrence (F(1,829) = 484.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.369, power = 1) (see Fig. 4). There was no significant interaction effect for sexual orientation, same- and opposite-gender harassment, or harasser gender; however, we did find a significant interaction for both gender (F(2,829) = 8.01, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.019, power = 0.956) and scenario( F(4,826) = 67.22, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.246, power = 1). Additional analyses of the effect of repeated behavior for each scenario showed that this effect was very large or large for scenario 1 (ηp2 = 0.383), scenario 3 (ηp2 = 0.204), and scenario 5 (ηp2 = 0.127), and medium for scenario 2 (ηp2 = 0.065) and scenario 4 (ηp2 = 0.085). Hence, the effect of repeated behavior was stronger for scenarios describing a date, homonegative comments, and objectifying comments.

Sexualized Physical Contact

Overall, there was a very strong effect for sexualized and non-sexualized physical contact (F(1,833) = 992.23, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.544, power = 1) (see Fig. 5). There was no significant interaction for sexual orientation, constellation, or gender of actor, but we did find a significant interaction for contact and gender (F(2,833) = 4.38, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.010, power = 0.757). We also found a significant interaction between contact and scenarios (F(2,832) = 169.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.290, power = 1), suggesting that the effect of sexual contact was not equal across the scenarios. The effect was particularly large for scenario 2 (ηp2 = 0.558), but any manifest sexualized touching in the Date scenario (ηp2 = 0.214) and Objectifying comment scenario (ηp2 = 0.267) clearly increased the rating of this behavior as sexual harassment.

Sexual Orientation of the Target and/or Actor

Finally, we examined Research Question 2 with a mixed model ANOVA how sexual orientation of either actor, target, or actor and target influenced perception of social-sexual behavior. For this analyzsis, we included only women and men, and contrasted the scores of the additional information of sexual orientation of the actor and/or target with the baseline rating for each scenario.Footnote 6 See Fig. 6 for an overview over all scenarios.

For the first scenario, asking a colleague out on a date, the additional information added was the target being a lesbian or gay. Here, we found a significant effect for sexual orientation of the target (F(1,817) = 567.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.410, power = 1), which shows participants rating this behavior more as sexual harassment when the target was a lesbian or gay. There were no significant effects for gender of participant, gender of harasser, or sexual orientation of participant. However, we did find a significant effect for gender constellation (F(1,817) = 293.63, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.264, power = 1), suggesting that the participants rated behavior more as sexual harassment when it took place between opposite-gender actor-target constellations compared to same-gender constellations.

The second scenario, a congratulating hug between colleagues, was tested with the additional features the target, the actor, or both target and actor being lesbian or gay. This analysis included only same-gender constellations. Again, we found a significant effect for sexual orientation (F(3,379) = 5.63, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.039, power = 0.933). As we can see from Fig. 6, being lesbian or gay identifying led to a higher perception of sexual harassment, when the target or the actor alone was a lesbian or gay, while when both target and actor were a lesbian or gay, at least for men, the perception was closer to the baseline again. We did not find any significant effects for gender or sexual orientation of participant, or gender of actor.

For the third scenario, the homonegative comment, additional features were the same as in the second scenario. We found a significant effect for sexual orientation (F(3,799) = 100.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.274, power = 1). In this scenario, those additional features led to less perception as sexual harassment (see Fig. 6). We did not find a significant moderating effect for gender of participant or sexual orientation; however, we did find significant moderating effects for gender of actor (F(3,799) = 15.55, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.055, power = 1), and gender constellation (F(3,799) = 9.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.035, power = 0.997). The behavior toward a lesbian or gay target was more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment when the actor was a male relative to female. For both female and male actors, the behavior was rated as least harassing when both actor and target were lesbian or gay. Same-gender behavior was more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment when displayed toward a lesbian or gay target, while opposite-gender behavior was perceived less as harassment in that case.

For the fourth scenario, the comment on low standards one has for their potential sexual partners, only the additional feature of target being lesbian or gay was collected. For this scenario, we did not find any effect of the target being lesbian or gay, nor any moderating effect for gender of participant, gender of actor, sexual orientation, or constellation.

For scenario 5, the objectifying comment on someone’s body, we found a significant effect of sexual orientation (F(3,397) = 15.37, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.104, power = 1). As we can see from Fig. 6, the perception of this behavior as sexual harassment was higher if the target or the actor was lesbian or gay, but not if both actor and target were lesbian or gay. We did not find a significant moderating effect for gender of participant or sexual orientation, but the gender of the actor affected the effect of being lesbian or gay (F(3,397) = 5.40, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.038, power = 0.930). Relative to the perception of behavior of male actors, the behavior of female actors was more likely to be perceived as harassment when the target was lesbian or gay.

Finally, for examining Research Question 3, we first analyzed how realistic and common participant found these scenarios to be across the four gender constellations.

With few exceptions, all scenarios were rated on average as realistic, with mean scores above 3.5 (see left panel of Table 1). The scenarios also differed with regard to how common they were perceived, and also differences across the gender constellations. For example, the scenarios describing a man asking a woman colleague for a date and a man giving homonegative comments to another man were both perceived as the most realistic and common scenarios, while a man giving body comments to another man was neither perceived very realistic nor common. Hence, objectifying comments (comments on someone’s body) were perceived as more realistic and more common when targeting women. Despite common stereotypes, comments on low standards were not perceived as more realistic or common when targeting women. If anything, the participants perceived these comments to be more common targeting men. However, the ratings of how realistic and common the scenarios were had no bearing on the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment when we added these ratings in the above analyses.

Discussion

In this preregistered study, we set out to create a more inclusive and wider perspective on sexual harassment perception. We therefore aimed to replicate earlier findings (Kessler et al., 2020), and to expand this research to include both same-gender social-sexual behavior and the perspective of LGBTQ + people (as participants, actors, and targets). These additions are central for providing a comprehensive understanding of sexual harassment to develop inclusive workplace interventions and ultimately reduce sexual harassment in the workplace.

In support of Hypothesis 1, women were more likely than men to perceive social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment. This is in line with previous findings (Kessler et al., 2020; Rotundo et al., 2001) and the effect size in this study was comparable to the prior findings. Furthermore, as part of the first hypothesis and in line with previous findings, we found that men perceive social-sexual behavior toward other men by women as less harassing, although the effect was somewhat smaller than in previous research (Kessler et al., 2020). As some of the scenarios are new, this might mean that the original finding is robust; however, the effect may be dependent to some degree on context. Cis women and transgender/genderfluid/non-binary people made less of a difference between female and male actors than cis men did, meaning that while women and transgender/genderfluid/non-binary people perceived the social-sexual behavior regardless of the gender of the target, while men made a difference between female and male targets. This could be because men, on average, hold more sexist attitudes than women (Kessler et al., 2021), and view the targeted genders differently. However, further research would be needed to confirm this. Participants of other gender identities rated social-sexual behavior more like cis women. Across gender, there was strong agreement to what degree the presented scenarios were rated as sexual harassment. In general, between colleagues, asking for a date after having been rejected once already, and giving a congratulatory hug, was not perceived clearly as harassment. Making comments regarding sexual orientation or low standards for one’s potential sexual partners, and particularly objectifying comments, was more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment. However, when specific prototypical #MeToo features, such as workplace status or repeated behavior, were introduced to the depicted situations, people’s perceptions changed as they tended to rate scenarios more as harassment when prototypical #MeTo features were introduced.

Aside from public and private settings, all presented prototypical #MeToo features increased the probability of social-sexual behavior to be perceived as sexual harassment, replicating findings from a previous study (Kessler et al., 2020), and studies prior to the #MeToo movement (Bursik & Gefter, 2011; Gordon et al., 2005; Lee & Guerrero, 2001; Rotundo et al., 2001). Those features are those that were present in almost all famously discussed #MeToo cases (see Appendix B for list over 262 sexual harassment cases). As such, the #MeToo movement and the media coverage of it may have influenced the perception of social-sexual behavior to some degree. However, as this study only examines those features post #MeToo, we cannot make any causal inferences. The effect of higher workplace status of the actor was strong, but not equally strong across the five scenarios; asking for a date, hugging someone, and making objectifying comments showed especially strong effects of the actor having a higher status. Similarly, repeating one’s behavior was considered especially problematic when asking for a date, as well as homonegative and objectifying comments. These situations in the workplace may seem difficult to escape from, and may influence one’s workplace environment, possibly over an extended period. This may be why those behaviors were especially perceived as harassment. However, we cannot say with certainty why prototypical #MeToo features affected certain scenarios more than others.

The public and private settings warrant further scrutiny. The only scenario that was more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment when happening in private was the congratulatory hug, while both the homonegative comment and the comment on someone’s low standards were clearly more likely to be seen as harassment when the comments were made in public. It is possible that behaviors such as a congratulatory hug are more likely to be perceived as harassment in private spaces because of the physical intimidation or threat, while nobody else is present. Being in a public place, one can seek help in others to end the hug, whereas in a private setting such aid from peers is not possible. Behaviors such as comments on one’s low standards are more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment in public because of social shaming. Others hear the comment and the reputation of the target of such comments might be more affected than in a private setting.

Generally, and with few exceptions, the scenarios were rated as realistic, and the behavior described as common. However, the degree to which participants perceived scenarios as realistic and common did not have an influence on general perception. Perhaps, less common behaviors show more variation in whether they are perceived as sexual harassment, but it seems that our scenarios are not new to the participants. This supports the ecological validity of the scenarios. More extreme (and hence unrealistic) scenarios also might have less validity in the everyday workplace environment. Less common scenarios could be perceived as more sexually harassing but would in our opinion not be as relevant for the general population and hence provide little value to the research questions.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the perspective of LGBTQ + people on sexual harassment perception. How people perceive sexual harassment does not seem to be contingent upon their sexual orientation. We did not find any differences in any of the scenarios between LGBTQ + people and heterosexual participants. Another of the current study’s important expansions was the addition of sexual orientation as a feature of actors and targets in the scenarios. We examined whether social-sexual behavior in the workplace would be perceived more or less as sexual harassment when the target, the actor, or both were lesbian or gay. The findings were not entirely consistent. When a gay/lesbian identifying person was targeted in scenarios involving asking for a date, congratulating hug, or an objectifying comment, participants were more likely to rate this as sexual harassment. The two other scenarios either resulted in no change in ratings relative to the baseline (low standards for sexual partners) or rating the behavior less as sexual harassment (homonegative comments). In the latter scenario, the behavior was least perceived as sexual harassment when both actor and target were gay or lesbian identifying. This might be explained by in-group behavior, which often legitimizes behavior as long as it takes place among members of the same group (O’Dea & Saucier, 2020). The same has been found for racial slurs, which can be deemed acceptable to use as long as only people of color use them for each other, but as unacceptable when used by people outside of that group (Croom, 2013). It is possible that these findings may show a similar phenomenon, as homonegative slurs may only be acceptable as long as they are used by and for gay or lesbian identifying people. However, even though such behavior might be more accepted in in-groups, homonegative comments are more likely to be perceived as sexual harassment compared to asking for a date and giving a congratulatory hug. These perceptions of homonegative comments may reflect the general perception of LGBTQ + people as a vulnerable group and that such comments discriminate against LGBTQ + people directly or indirectly.

Social and Public Implications

This study provides some practical implications to the field of workplace sexual harassment. Even before, but especially after the #MeToo movement, organizations have aimed to reduce sexual harassment in the workplace using anti-harassment policies and trainings as well as an easier system to report sexual harassment. While a meta study has shown anti-harassment trainings to have some effects, such as a higher rate of filing sexual harassment claims, and more success defending these claims, as well as an increase in knowledge (Roehling & Huang, 2018), there is little to no evidence that the frequency of sexual harassment incidences has actually decreased (Dobbin & Kalev, 2017; Grossmann, 2019; Roehling & Huang, 2018). Interventions and policies should include the feedback and wishes of all parties to be effective (Firestone & Harris, 2003). This of course should include all gender identities and sexual orientations. The fact that different types of sexual harassment are perceived differently shows that interventions should not talk about sexual harassment in general, but specifically focus on different types of specific behaviors in specific contexts and constellations of gender and sexual orientation. Moreover, men rated social-sexual behaviors less as harassment than other genders, especially when the actor was female, showing that more education on actor and target dynamics may be warranted. Organizations should also include prototypical #MeToo features in interventions, to illustrate how a situation might be more or less undesired and therefore experienced as harassment under different circumstances. Finally, moral panicking should be addressed in interventions. This study shows that overall, people across gender and sexual orientation agree on what behavior should be categorized as sexual harassment. Flirting in the workplace, such as asking someone out on a date, is generally not seen as sexual harassment. The same goes for homonegative comments; while there is evidence for associations with negative mental health outcomes for those subjected to homonegativity (DeLay et al., 2017), a single comment will most likely not be perceived as harassment. This is important, as it shows that there are no reasons not to advance a diverse workplace. Research has shown that sexual harassment is more likely to happen in male-dominated organizations (Schultz, 2003), and that diverse workspaces therefore may be part of the solution to reduce sexual harassment (Dobbin & Kalev, 2017). One might infer from the current findings that there is no justification for moral panicking.

Limitations

Although the five scenarios were generally rated as realistic and common, supporting the validity of the measurement, we are not suggesting that they reflect the entire spectrum of social-sexual behaviors that may occur in a work environment. Furthermore, we do not know how well each scenario reflects the perception of real-life experiences when it comes to sexual harassment in the workplace. We also acknowledge that the wording for the scenario covering homonegative comments toward a man or a woman needed adjustment to cover the differential stereotypical beliefs people may hold against people identifying as gay or lesbian. Still, we believe the differential wording does reflect the same underlying behavior. Furthermore, while we did aim to oversample LGBTQ + people, and had a considerable group, we did have to merge those identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, or another sexual orientation into one group. People of different sexual orientations may however differ on several aspects related to their work life, and by merging them, some details may have been lost. However, this study did not find any effects of sexual orientation overall, and the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment may not depend strongly on the sexual orientation of the participant.

We chose to apply a mixed design with the five scenarios as within-subject factor. Although this maintains power at lower numbers of participants compared to a between design, such a design may introduce the problem of order and anchoring effects. We did not counterbalance the order of the five scenarios nor the additional features withing each scenario. However, the participants were clearly instructed to first rate each behavior on a general basis, followed by new assessments when additional information was provided. We believe these instructions may have reduced the type of anchoring resulting in reduced variance in subsequent items observed in blocking of items with similar content (Gehlbach & Barge, 2012). Although the five scenarios described highly diverse socio-sexual behaviors, possible order effects due to the fixed presentation of the scenarios remain unknown.

The use of difference scores is discussed thoroughly in the statistical literature (e.g., Edwards, 2001) and their use is somewhat controversial. However, when researchers want to study how different experimental conditions affect responses to a measure, such as in this study of additional features, a difference score is the natural measure and easily interpretable.

Finally, the representativeness of the sample is not known as the link to the survey was distributed through social media using snowballing and procedures that do not secure representativeness. The study was shared by university students and shared by Facebook contacts. Furthermore, the study was posted using the words terms #MeToo and sexual harassment, which may have led some people to answer or avoid answering the survey. On the other hand, this sample included a relatively high number of participants from the LGBTQ + community, across a wide age range, and with work experience. Despite this, some of the analyses lack power, particularly those involving non-cis gender. Future research should aim to replicate these findings in other cultural backgrounds, with representative samples, and include more detailed grouping and analysis of specific LGBTQ + people.

Conclusion

This is the first study to examine the perception of same-gender social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment. It is also the first study to include various sexual orientations and gender identities. Transgender/genderfluid/non-binary participants generally agreed with the ratings from cis women, while cis men perceived social-sexual behavior less as harassment. However, the current study shows that there was considerable consensus as to what sexual harassment entails in the five scenarios across gender identity and sexual orientation. This was also true for the effect of prototypical #MeToo features, which led to higher perception of sexual harassment for all groups. The current study, using similar methodology, largely replicates findings from earlier research suggesting that people in general have a common understanding of what sexual harassment consists of (Kessler et al., 2020).

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code

IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used for data analyses.

Notes

Gender constellations describe the different genders of both actor and targets in which sexual harassment may happen, meaning the following four constellations: female actor-female target, female actor-male target, male actor-female target, and male actor-male target.

The project was outlined with specific hypotheses and research questions prior to data collection. Neither hypotheses nor research questions can be changed after data collection.

While we cannot change the preregistered hypothesis, we will also analyze all people outside of the gender dichotomy.

The exclusion of those older than 60 did not affect the findings.

This is the natural measure when one is interested in the difference between two conditions as in this case (Edwards, 2001). The advantage of using difference scores is the ease of interpretation as they contrast one condition with another.

Power issues emerged when persons in the gender category other (n = 42) were included in the analyses.

References

Alicke, M. D., & Weigel, S. H. (2021). The reasonabe person standard: Psychological and Legal Perspectives. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 17. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-111620-020400

Alvinius, A., & Holmberg, A. (2019). Silence-breaking butterfly effect: Resistance towards the military within #MeToo. Gender Work Organization, 26, 1255–1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12349

Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., Taylor, S. N., & Tringale, A. (2021). The era of #MeToo and what managers should do about it. Business horizons, 64, 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.12.006

Bendixen, M., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2017). Advances in the understanding of same-sex and opposite-sex sexual harassment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38, 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/2017.01.001

Bitton, M. S., & Shaul, D. B. (2013). Perceptions and attitudes to sexual harassment: An examination of sex differences and the sex composition of the harasser–target dyad. Journal of applied social psychology, 43, 2136–2145. https://doi.org/10.1111/12166

Bursik, K., & Gefter, J. (2011). Still stable after all these years: Perceptions of sexual harassment in academic contexts. Journal of Social Psychology, 151, 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224541003628081

Caputi, T. L., Nobles, A. L., & Ayers, J. W. (2019). Internet Searches for Sexual Harassment and Assault, Reporting, and Training Since the #MeToo Movement. JAMA internal medicine, 179, 258–259. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5094

CBS. (2017). More than 12 million “Me too” facebook posts, comments, reactions in 24 hours. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/metoo-more-than-12-million-facebook-posts-comments-reactions-24-hours/

Croom, A. (2013). How to do things with slurs: Studies in the way of derogatory words. Language and Communication, 33, 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2013.03.008

DeLay, D., Hanish, L. D., Zhang, L., & Martin, C. L. (2017). Assessing the impact of homophobic name calling on early adolescent mental health: A longitudinal social network analysis of competing peer influence effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 955–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0598-8

Dobbin, F., & Kalev, A. (2017). Training programs and reporting systems won’t end sexual harassment. Promoting more women will. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2017/11/training-programsand-reporting-systems-wont-end-sexual-harassment-promoting-more-women-will

Edwards, J. R. (2001). Ten difference score myths. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 264–286.

Ennis, E., & Wolfe, L. (2018). Media and #MeToo: How a movement affected press coverage of sexual assault. Women’s media center. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from http://www.womensmediacenter.com/assets/site/reports/media-and-metoo-how-a-movement-affected-press-coverage-of-sexual-assault/Media_and_MeToo_Womens_Media_Center_report.pdf

Ellis, S., Barak, A., & Pinto, A. (1991). Moderating effects of personal cognitions on experienced and perceived sexual harassment of women at the workplace. Journal of applied social psychology, 21, 1320–1337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1991.tb00473.x

Fineran, S. (2002). Sexual harassment between same-sex peers: Intersection of mental health, homophobia, and sexual violence in schools. Social Work, 47, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/47.1.65

Firestone, J. M., & Harris, R. J. (2003). Perceptions of Effectiveness of Responses to Sexual Harassment in the US Military, 1988 and 1995. Gender, Work & Organization, 10, 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00003

Gehlbach, H., & Barge, S. (2012). Anchoring and Adjusting in Questionnaire Responses. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34, 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.711691

Golden, J. H., Johnson, C. A., & Lopez, R. A. (2001). Sexual harassment in the workplace: Exploring the effects of attractiveness on perception of harassment. Sex Roles, 45, 767–784. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015688303023

Gordon, A. K., Cohen, M. A., Grauer, E., & Rogelberg, S. (2005). Innocent flirting or sexual harassment? Perceptions of ambiguous work-place situations. Represent of Research on Social Work Practice, 28, 47–58.

Gutek, B. A., Morasch, B., & Cohen, A. G. (1983). Interpreting social-sexual behavior in a work setting. Journal of vocational behavior, 22, 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(83)90004-0

Grossman, J. L. (2019). Small steps forward: New York legislature increases protections for sexual harassment victims. Justia Verdict. Retrieved August 24, 2021, from https://verdict.justia.com/2019/07/16/small-steps-forward-new-york-legislature-increases-protections-for-sexual-harassment-victims

Hemmings, C. (2018). Resisting popular feminisms: Gender, sexuality and the lure of the modern. Gender, Place & Culture, 25, 963–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1433639

Hendrix, W. H., Rueb, J. D., & Steel, R. P. (1998). Sexual harassment and gender differences. Journal of Social Behavior, 13, 235–252.

Hurt, L. E., Wiener, R. L., Russell, B. L., & Mannen, R. K. (1999). Gender differences in evaluating social-sexual conduct in the workplace. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 17, 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0798(199910/12)17:4<413::AID-BSL364>3.0.CO;2-B

Kath, L. M., Bulger, C. A., Holzworth, R. J., & Galleta, J. A. (2014). Judgments of sexual harassment court case summaries. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9355-8

Kennair, L. E. O., & Bendixen, M. (2012). Sociosexuality as predictor of sexual harassment and coercion in female and male high school students. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33, 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.01.001

Kessler, A. M., Kennair, L. E. O., Grøntvedt, T. V., Bjørkheim, I., Drejer, I., & Bendixen, M. (2020). The effect of prototypical #MeToo features on the perception of social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment. Sexuality & Culture, 24(5), 1271–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09675-7

Kessler, A. M., Kennair, L. E. O., Grøntvedt, T. V., Bjørkheim, I., Drejer, I., & Bendixen, M. (2021). Perception of workplace social-sexual behavior as sexual harassment post #MeToo in Scandinavia. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12763

Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., Kull, R. M., & Greytak, E. A. (2013). The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of in-school supports. Journal of School Violence, 12, 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.732546

Larsen, C. S. (2003). Equality for the sexes in human evolution? Early hominid sexual dimorphism and implications for mating systems and social behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 9103–9104. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1633678100

Lee, J. W., & Guerrero, L. K. (2001). Types of touch in cross-sex relationships between coworkers: Perceptions of relational and emotional messages, inappropriateness, and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 29, 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880128110

McCabe, M. P., & Hardman, L. (2005). Attitudes and perceptions of workers to sexual harassment. Journal of Social Psychology, 145, 719–740. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.145.6.719-740

McMaster, L. E., Connolly, J., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. M. (2002). Peer to peer sexual harassment in early adolescence: A developmental perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579402001050

Nielsen, M. B., Bjørkelo, B., Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. (2010). Sexual harassment: Prevalence, outcomes, and gender differences assessed by three different estimation methods. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19, 252–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771003705056

North, A., Grady, C., McGann, L., & Romano, A. (2020). 262 celebrities, polititians, CEOs, and others who have been accused of sexual misconduct since April 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2022, from https://www.vox.com/a/sexual-harassment-assault-allegations-list

Norwegian Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act. (2017). Act relating to equality and a prohibition against discrimination (LOV-2017-06-16-51). Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/2017-06-16-51

O’Dea, C. J., & Saucier, D. A. (2020). Perceptions of racial slurs used by black individuals toward white individuals: Derogation or affiliation? Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39, 678–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X20904983

Onwuachi-Willig, A. (2018). What about #UsToo: The invisibility of race in the #MeToo movement. Yale LJF, 128, 105.

Roehling, M. V., & Huang, J. (2018). Sexual harassment training effectiveness: An interdisciplinary review and call for research. Journal of Organization Behavior, 39, 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/JOB.2257

Rosch, E. (1999). Principles of categorization. In E. Margolis & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core readings 189–206). London: The MIT Press.

Rotundo, M., Nguyen, D. H., & Sackett, P. R. (2001). A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 914–922. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.914

Rudman, L. A., & Goodwin, S. A. (2004). Gender differences in automatic in-group bias: Why do women like women more than men like men? Journal of personality and social psychology, 87, 494–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.494

Runtz, M. G., & O’Donnell, C. W. (2003). Students’ perceptions of sexual harassment: Is it harassment only if the offender is a man and the victim is a woman? Journal of applied social psychology, 33, 963–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01934.x

Sandberg, S., & Pritchard, M. (2019). The number of men who are uncomfortable mentoring women is growing. Fortune. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://fortune.com/2019/05/17/sheryl-sandberg-lean-in-me-too/

Schultz, V. (2003). The sanitized workplace. Yale Law J., 112, 2061–2193.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (1980). EEOC compliance manual. [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1000674188

Zarkov, D., & Davis, K. (2018). Ambiguities and dilemmas around #MeToo: #ForHow Long and #WhereTo? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506817749436

Zurbrügg, L., & Miner, K. N. (2016). Gender, sexual orientation, and workplace incivility: Who is most targeted and who is most harmed? Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00565

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Andrea Melanie Kessler: conceptualization, data collection, data analyses, writing. Leif Edward Ottesen Kennair: conceptualization, writing. Trond Viggo Grøntvedt: conceptualization, writing. Mons Bendixen: conceptualization, data analyses, writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

As the study was completely anonymous, the study did not have to be approved by any national committee (following those committees guidelines).

Informed Consent

The participation was both voluntary and anonymous. Participants gave their informed consent electronically by approving their responses at the final page of the questionnaire.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kessler, A.M., Kennair, L.E.O., Grøntvedt, T.V. et al. The Influence of Prototypical #MeToo Features on the Perception of Workplace Sexual Harassment Across Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation (LGBTQ +). Sex Res Soc Policy (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00850-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00850-y