Abstract

Introduction

There is a growing interest in legislation and policies regarding sex work in the European Union and a debate between two opposite perspectives: prostitution is a form of gender violence or a work lacking legal and social recognition. This review aims to develop an integrative synthesis of literature regarding the impact of prostitution policies on sex workers’ health, safety, and living and working conditions across EU member states.

Methods

A search conducted at the end of 2020 in bibliographic databases for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods peer-reviewed research, and grey literature published between 2000 and 2020 resulted in 1195 initial references eligible for inclusion. After applying the selection criteria, 30 records were included in the review. A basic convergent qualitative meta-integration approach to synthesis and integration was used. The systematic review is registered through PROSPERO (CRD42021236624).

Results

Research shows multiple impacts on the health, safety, and living and working conditions of sex workers across the EU.

Conclusions

Evidence demonstrates that criminalisation and regulation of any form of sex work had negative consequences on sex workers who live in the EU in terms of healthcare, prevalence and risk of contracting HIV and STIs, stigmatisation and discrimination, physical and sexual victimisation, and marginalisation due to marked social inequalities, for both nationals and migrants from outside the EU.

Policy Implications

The evidence available makes a strong case for removing any criminal laws and other forms of sanctioning sex workers, clients, and third parties, which are prevalent in the EU, and for decriminalisation. There is a need for structural changes in policing and legislation that focus on labour and legal rights, social and financial inequities, human rights, and stigma and discrimination to protect cis and transgender sex workers and ethnical minorities in greater commitment to reduce sex workers’ social inequalities, exclusion, and lack of institutional support. These measures could also positively impact reducing and monitoring human trafficking and exploitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent decades, in Europe Union (EU) and worldwide, the discussions about sex work exacerbated, and many countries changed their legislation. However, contrary to what would be expected, these discussions and changes were not based on scientific evidence (Outshoorn, 2018; Wagenaar & Jahnsen, 2018). This meant that policies are often made in the name of moral and ideological stances, with little concern about their impact on sex workers.

Nevertheless, many studies indicate that the legislation has different impacts on the health, safety, and living and working conditions of sex workers. For example, the laws criminalising sex workers have been recognised by scholars as having a huge impact on the health, safety, and human rights of sex workers (e.g. Armstrong, 2017; Deering et al., 2014; Platt et al., 2018; Shannon et al., 2015; Vanwesenbeeck, 2017). The idea that decriminalising sex work can assure safer working conditions and guarantee human rights has also been supported by many agencies, like UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund), UN Women (United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women), UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS), and UNDP (United Nations Development Programme); and relevant human rights and anti-trafficking organisations, such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and La Strada International (Macioti & Geymonat, 2016; Macioti et al., 2022; TAMPEP, 2015).

Another problem is related to the lack of research in some areas. Although there is already an extensive and robust body of research on prostitution internationally, if we focus on investigations on specific aspects and geographies and if we only look at peer-reviewed studies, we find several gaps. More specifically, we have found little research on the legislative models and policies regarding sex work in the EU, particularly their impact on sex workers’ health, safety, and living and working conditions in EU member states.

Regarding prostitution laws, the 27 EU countries are diverse, ranging from countries that almost fully criminalise this activity to countries that regulate it and allow it to be exercised as a profession. Even in the context of countries that regulate the activity, some do so through criminal laws, others through licensing systems. This not only means a lack of consensus but also sheds light on the issue’s complexity. For example, we find many typologies based on different concepts or emphasising different aspects when classifying and grouping the diverse legislative approaches, from the most common typology that divides them into prohibitionist, abolitionist, or regulations to classifications using other concepts as criminalisation, legalisation, and decriminalisation. The expressions are so many (e.g. criminalisation, neo-criminalisation, regulation, legalisation, licensing, decriminalisation, abolitionism, neo-abolitionism) and are defined, combined, and applied in different ways that sometimes it becomes difficult to use them as analytical categories and classification devices (Östergren, 2017). The classification of legislative models related to sex work adopted in the present study involves two broad legislative categories of approaching prostitution: “Criminalisation” and “Regulation”. These categories seem consistent, consider the law’s effects on sex work, and condense what appears to be the legislator’s or policy regime’s goal, providing a valuable tool for examining the various laws (Oliveira et al., 2020). Within the “Criminalisation” category, we include two subcategories considering both partial criminalisation regimes: “Criminalisation and other forms of legal sanctioning of sex workers” and “Criminalisation and other forms of legal sanctioning of third parties and/or clients but not sex workers”. Table 1 describes the categories and subcategories and indicates which countries we included in each. However, we should mention a third legislative category for which we had not found any EU country when conducting this study: “Decriminalisation”. According to this category, sex work is considered a regular profession, and there is an abolition of all criminal laws aimed explicitly at prostitution. However, there may be some regulation according to labour laws. The country which is a reference when it comes to decriminalising sex work is New Zealand. Although the New Zealand case has more recently come to be defined as “partial decriminalisation” (Macioti et al., 2022): The 2003 Prostitution Reform Act that decriminalised sex work for New Zealand citizens and permanent residents excluded migrants from its protection, and migrants can be deported if found working as sex workers (Bennachie et al., 2021). In Belgium, since 2022, prostitution has been decriminalised, becoming the first country in the EU and Europe to do so. Apropos this remark, it is also worth mentioning that legislative changes have occurred in some countries during the time interval defined for this literature review, i.e. between 2000 and 2020. Such are, for example, the cases of France (in 2016, it became criminalised the demand for paid sex), Finland (since 2003, selling or buying sexual services in public places is criminalised, although prostitution is not a crime), or Spain (the general law remained the same, but there were some changes at the Municipalities' level). Thus, depending on the dates of the investigations included in the literature review, this can be reflected in the obtained data.

Systematic literature reviews are relevant for several reasons. Research is guided by different paradigms, methodological options, and objectives which may lead to inconsistent or contradictory results. Furthermore, scientific research sometimes contains methodological inconsistencies, is carried out with non-representative samples, and may incur abusive generalisations, contributing to conclusions without strong empirical support (Wagenaar et al., 2017; Weitzer, 2005). This is the problem with using single studies as they can often be biased, methodologically flawed, highly time context–dependent and the results can be misinterpreted and misrepresented (Wilson & Petticrew, 2008). Whether made by the research authors or third parties, these misinterpretations and misrepresentations may not be immune to the ideological debate on this topic. As Weitzer (2005) defended, in no other domain of social sciences has knowledge been so ideologically contaminated. Thus, it is relevant and urgent to conduct systematic reviews that can inform policies aimed at people involved in the sex trade. Since systematic reviews aim to identify, evaluate, and summarise the findings of all relevant individual studies (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2001), it becomes a very useful tool for informing policymakers.

A preliminary search of databases (JBI Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Google scholar) has been undertaken and found four systematic reviews that studied the relationship between policy and sex workers’ health (Footer et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2017; Platt et al., 2018; Shannon et al., 2015) and one that studied the link between policies and violence towards sex workers (Deering et al., 2014), that covered very few EU countries. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to address the link between EU policies towards sex work and the health, safety, and living and working conditions of sex workers in the EU member countries.

Therefore, the present study was conducted to synthesise the available scientific evidence and grey literature on the subject. Specifically, our research views to answer the following questions: (1) How do prostitution policies in different EU member states impact the health, safety, and living and working conditions of sex workers? and (2) What are the opportunities and constraints posed by these different types of policies on the lives of sex workers?

Methods

This systematic review was designed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) and the Johanna Briggs Institute guidelines for systematic reviews (Aromataris & Munn, 2020). Mixed studies reviews can provide comprehensive, rich, and practical information about complex phenomena capable of informing policies rigorously (Pluye & Hong, 2014; Frantzen & Fetters, 2016). The protocol was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO CRD42018105225) (Lemos & Oliveira, 2021).

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

A systematic search of peer-reviewed research articles and grey literature was conducted. Grey literature (evidence not published in commercial publications, such as academic papers, research reports, or conference papers) can contribute to systematic reviews by reducing publication bias, increasing reviews’ scope, and providing a more comprehensive view of the evidence available (Paez, 2017). Databases such as PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Academic Search Ultimate, and Sociology Search Ultimate were searched for peer-reviewed quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. Sources of unpublished studies and grey literature included Open Grey, Google Scholar, Research for Sex Work, Open Society Foundation, and TAMPEP websites. The search was limited to studies in English, Portuguese, French, and Spanish, published between 2000 and 2020. It used controlled vocabulary combinations to identify articles that included terms from each of these domains: sex work AND policy OR legislation AND health OR safety OR living and working conditions. The words in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles were used to develop a full search, and reference lists of relevant studies were hand-searched for additional published or unpublished work.

The inclusion criteria were determined a priori in terms of PICo (Population, Phenomena of interest, Context). This review considered studies that included adult cis and transgender sex workers and investigated the association between EU member states’ legal frameworks and sex workers’ experiences and perceptions concerning health (which includes access to healthcare, physical health, such as incidence of diseases such as HIV and other sexuality transmitted infections (STIs), and mental health), safety (including multiple forms of violence, social stigma, and police protection), and living and working conditions in the 27 EU member states. We define a sex worker as someone who receives money or goods in exchange for sexual services and participates in the sex trade consciously and voluntarily (Weitzer, 2000). This review considered peer-reviewed studies and grey literature involving quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. Inclusion criteria for quantitative research considered studies that examined the impact or associations of different EU policies on prostitution on the health, safety, and living and working conditions of sex workers, and there were no restrictions on study design, study duration, follow-up period, intervention strategies, and control condition or on who delivered the intervention. Inclusion criteria for qualitative research considered studies that explored sex workers’ perspectives on how the different prostitution policies have shaped their experiences in terms of health, safety, and living and working conditions. Studies published from 2000 to, 2020 were included as this timeframe coincides with the change in policies related to prostitution, namely the implementation, in 1999, of the Swedish Model, which was later adopted in other countries of the EU, and which has sparked growing debate and research (Table 2).

Study Selection and Methodological Quality Assessment

Following the search, all identified citations were loaded into Endnote X9, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers selected the documents in a two-step process. First, titles and abstracts were screened for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full and assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by both reviewers using Rayyan QCRI software.

All studies considered eligible for inclusion were assessed for methodological quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Pluye et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2018), and grey literature was critically appraised using the Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, and Significance checklist (AACODS) (Tyndall, 2010) (Tables 3 and 4). Any disagreements between the reviewers at each stage of the study selection process were resolved through discussion in deliberation sessions.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods documents were then segregated and categorised into Qual and Quan, and data were extracted from studies included in the review by two independent reviewers into two summary tables (Tables 3 and 4), using the JBI mixed methods data extraction form (Lizarondo et al., 2020), to inform researchers of the heterogeneity of the research papers and grey literature. This included specific details about context, legislative model, participants, methodology, methods, the aim of the study, description of significant findings, and any relevant conclusions relating to the review questions.

This review used a basic convergent qualitative meta-integration approach to data synthesis and integration, which involved transforming quantitative data into “qualitised” data, through narrative interpretation of the quantitative results to respond directly to the review questions. According to Munn et al. (2014), this method has been developed to deliver readily usable synthesised findings to inform decision-making at the clinical or policy level.

Both qualitative data and “qualitized” data (Quan = Qual) were subject to thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998) using NVIVO software (1.0), which involved a hybrid deductive inductive approach (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006) through the development of an initial template of three broad categories (Health, Safety, and Living and Working Conditions) based on the research questions and subsequent coding. Within each theme, attention was paid to patterns related to legal frameworks according to the legislative classification adopted. The analysis process and integration of findings were conducted in four stages (through an intra-method analysis and synthesis, informed by comparison of both datasets; subsequent inter-method integration to respond to the research questions; data arrangement; and drawing conclusions). According to Frantzen and Fetters (2016), this iterative process ensures the final synthesis is based on results from all types of studies and grey literature to create new insights and knowledge.

Results

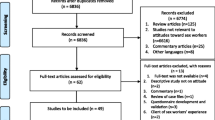

From a total of 1195 records identified, 30 were included in the review. Eighteen studies (n = 18) were included in the synthesis of peer-reviewed literature (seven quantitative, nine qualitative, and two mixed methods studies), and twelve records (n = 12) were included in the synthesis of grey literature (Fig. 1: PRISMA flow chart).

The peer-reviewed articles covered 18 EU countries (Table 3). As for grey literature, the papers covered 23 countries of the EU (Table 4). None of the included literature focused on Ireland or Malta. As for the type of legal frameworks represented in this review, the studies are diverse: 15 peer-reviewed studies represented partial criminalisation (without criminalising sex workers), five studies represented regulation, and another two studies represented almost full criminalisation (including sex workers).Footnote 1

Within the three main theoretical themes, the following core categories were identified: Restricted access to healthcare, Increased physical health risks, and Increased mental health risks (Theme 1, Health); Relationship with police and access to Justice, Increased financial, physical, and sexual violence, Risks and inequalities related to stigma (Theme 2, Safety); and Changes in working conditions and spatial displacement and Social inequalities and isolation (Theme 3, Living and working conditions) (full categories presented in Table 5).

Theme 1: Health

Restricted Access to Healthcare

Research showed that multiple factors restricted sex workers’ access to proper healthcare. Criminalisation and police enforcement interfered with sex workers’ right to health services and information, particularly with preventing, testing, and treating STIs and HIV (Amnesty International, 2016). In countries where sex work is almost fully criminalised, including sex workers, like Lithuania, Croatia, or Romania,Footnote 2 sex workers had minimal access to healthcare and HIV prevention due to a lack of effective strategies to respond to sex work settings becoming more mobile and clandestine, as a result of the criminalisation of clients (TAMPEP, 2007). Lack of comprehensive geographic, temporal, and sex work setting coverage (Bulgaria and the Czech Republic), non-recognition of labour rights, forcing sex workers to obtain health insurance on grounds other than their sex work, lack of information and knowledge about existing health services (TAMPEP, 2007, 2009), and mental health problems (Le Bail et al., 2019) were also barriers to access healthcare in partially criminalised contexts. Evidence showed that two main barriers to access healthcare for nationals in all legal contexts were stigma and discrimination by healthcare providers (Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017). Criminalisation also showed to have a negative impact on HIV prevention efforts, specifically “End demand” policies, due to condom confiscation and citations by police as evidence of sex work offences (Amnesty International, 2016; Global Network of Sex Work Projects [NSWP], 2018), fear of prejudices by authorities, and lack of access to prevention services for the majority of sex workers in Sweden (NSWP, 2018).

As for migrant sex workers from outside the EU, a considerable part of the total number of sex workers in the EU, policies concerning sex work and migration, and sex workers’ immigration status are key predictors of their vulnerability, according to several studies (TAMPEP, 2007, 2009; Tokar et al., 2020; NSWP, 2018; Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017). These studies show that this population faced even more hardships in accessing health services in all legal contexts: many were not aware of existing health services due to language barriers, had negative experiences in their countries of origin related to healthcare providers, and feared providing information about their activities, keeping away from official records to avoid arrest or deportation. HIV treatment and healthcare for non-health insured and undocumented sex workers were unavailable in multiple EU countries (e.g. Sweden, Romania, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Germany, The Netherlands, Denmark, and Finland) (TAMPEP, 2007). In The Netherlands, a regulation context, according to Tokar et al. (2020), government organisations and municipal prostitution policies used a combination of providing healthcare and several control measures, which limited the accessibility of health services for migrant sex workers. Also, the same study states that focusing on regular check-ups and “supervision” of licensed sex work spaces resulted in unlicensed spaces and Internet-based sex workers falling below the radar since they could not be included in the legal framework. Spatial segregation and stigma, such as discriminatory treatment or viewing migrant workers as trafficking victims, and self-stigmatisation were also factors that discouraged migrant workers from resorting to healthcare services (Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017; Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; NSWP, 2018; Tokar et al., 2020) across contexts. As for factors that facilitated migrant workers’ access to health in The Netherlands, evidence shows that having a family, working in a venue, and trust in social services were protective factors (Tokar et al., 2020). In countries like Bulgaria and Portugal, reports showed that universal access to healthcare, part of government healthcare policies, was also a facilitator for these sex workers (INDOORS, 2014). France provided an example of the most comprehensive range of HIV prevention, counselling, testing, and treatment services for undocumented migrants from any country in Europe (TAMPEP, 2007).

Increased Physical Health Risks

Evidence showed that the effectiveness and fairness of enforcement partially moderated the relationship between sex work policy and HIV among sex workers. Reeves et al. (2017) found that in countries where sex work was regulated, HIV prevalence was lower than in countries where sex work was criminalised. These authors demonstrated that where selling sex was legal, but brothels were not, there was less HIV than in countries where sex work was criminalised, and this association was stronger in countries that legalised profiting from all forms of sex work (including brothels)—for example, HIV prevalence was lower in Germany (where procurement was legalised) than in Sweden (where the so-called Swedish Model was in force). Another study, consisting of a theoretical economic model, pointed out that prohibition could effectively reduce the number of infected individuals in the market, but not the best policy to reduce harm (Immordino & Russo, 2015). Economic pressure, social exclusion, self-care practices, and less ability to negotiate with clients also increased risks of HIV and STIs for national and migrant workers in countries where sex work was partially criminalised but not sex workers, like France, Spain, or Bulgaria (INDOORS, 2014; Le Bail et al., 2019; Oso, 2016; Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017). In Sweden, HIV risk increased due to a lack of harm reduction and effective condom distribution strategies (Levy, 2013; Levy & Jakobsson, 2014; NSWP, 2018). Research also showed that police violence increased exposure to HIV and STIs risks in countries where sex work was criminalised through sex workers’ marginalisation and fear of arrest and prosecution (Sex Workers’ Rights Advocacy Network [SWAN], 2009; INDOORS, 2014; Reeves et al., 2017). In partially criminalised (criminalisation of third parties and/or clients but not sex workers) and regulatory contexts, where there was a strict licensing system for HIV screening, more severe screenings of sex workers implied more infected individuals in the illegal market and fewer in the legal market (Immordino & Russo, 2015).

Increased Mental Health Risks

Studies showed context was central to sex workers’ mental health in criminalisation and regulation frameworks. Stigma and stigma-related experiences were the most critical factors contributing to stress, burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, depersonalisation, feelings of guilt, and low self-esteem in sex workers in countries where sex work was criminalised or regulated (Pajnik & Radacic, 2020; Vanwesenbeeck, 2005; Villacampa & Tones, 2013). In Croatia, where sex work was fully criminalised (including sex workers), public perceptions of prostitution that involved violence and exploitation were projected onto sex workers and had a negative impact on their mental health, causing feelings of self-contempt and guilt (Pajnik & Radacic, 2020).

In The Netherlands, having experienced violence was associated with greater PTSD, burnout, feelings of intrusion (Krumrei-Mancuso, 2017; Vanwesenbeeck, 2005), and fear of police and authorities.

Regarding the impact of working conditions on mental health, another factor contributing to increased burnout in sex workers appears to be the lack of a worker-supportive organisational context rather than the work itself, as Vanwesenbeeck (2005) showed. Additionally, this author argued that depersonalisation was explained by not working by choice and lack of control in client interaction.

Workplaces also impacted sex workers’ mental health. Evidence suggested engaging in street prostitution was associated with PTSD (Vanwesenbeeck, 2005) and higher levels of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal than those experienced by people who worked in brothels, from home, or in a combination of settings that did not include working outdoors (Krumrei-Mancuso, 2017).

Lack of clients and consequent increase in working time due to financial pressure in the context of clients’ criminalisation led to stress and extreme fatigue in France (Le Bail et al., 2019).

In Spain, migrant workers’ mental health was negatively influenced by a lack of social support, fear of contracting STIs, and financial pressure to provide to families abroad due to municipal bans on street prostitution and stigma (Rios-Marin, 2016; Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017; Villacampa & Tones, 2013).

Finally, female indoor sex workers in The Netherlands, a regulation context, did not exhibit a higher level of work-related emotional exhaustion or a lower level of work-related personal competence than a comparison group of female healthcare workers, according to Krumrei-Mancuso (2017). This study found that not only their experience at work threatened sex workers’ health, but the acceptance of their professional choice in their private lives also appeared particularly important. Having a sense of fair treatment from others and self-acceptance were both associated with better mental health and less PTSD (Vanwesenbeeck, 2005).

Theme 2: Safety

Relationship with Police and Access to Justice

Research showed that the relationship with the police and the Justice system was marked by distrust, fear, violence, and lack of protection in countries where sex work was criminalised (Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; Tokar et al., 2020; Oso, 2016; Levy & Jakobsson, 2014; Villacampa & Tones, 2013; Rios-Marin, 2016; Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women [GAATW], 2018). The main reasons for police distrust, evidenced by reviewed studies, were fear of being sanctioned under city ordinances in Spain, where, according to sex workers, fines were mainly aimed at women working on the street and not so at clients (Villacampa & Tones, 2013); and fear of being evicted in Sweden, due to third-party regulations, leading sex workers not to report violent crimes, such as rapes, robberies, or beatings (Vuolajärvi, 2019). In Spain, most participants linked municipal ordinances to a change in the role of the police, from protection to control agents, since they were in charge of imposing the fines provided by the civic ordinances (Villacampa & Tones, 2013). Raids to arrest undocumented migrants from outside the EU, particularly in brothels, created insecurity among sex workers. Furthermore, none of the women interviewed by Villacampa and Tones (2013) received counselling by police officers about the possibility of being directed to social services so that they could be informed of the resources available.

Studies also showed that harassment, beatings, and threats by the police were common in criminalised contexts (e.g. Slovakia) (SWAN, 2009; INDOORS, 2014; Amnesty International, 2016).

Threats of deportation of third-country nationals in Sweden were common, which justified migrant sex workers’ fears of reporting crimes to the police since policies towards prostitution and immigration laws were intertwined in practice (Vuolajärvi, 2019). In Sweden, the police actively enforced the Sex Purchase ActFootnote 3 by checking the papers of those who worked on the street, something that sex workers perceived as a form of control and intimidation (Levy & Jakobsson, 2014). According to sex workers, Swedish police officers visited them at their homes, threatening and forcing them to leave or accusing the owner of committing a crime under third-party laws (Levy & Jakobsson, 2014; Vuolajärvi, 2019). In Finland, the law that partially criminalises the buying of sexual services does not seem to have had such negative consequences in the lives of people who sold sex since buying was only criminalised if from a person who was trafficked or pimped, so the police mainly enforced the law through pimping and trafficking investigations and convictions (Vuolajärvi, 2019). Research also showed that sex workers restricted access to Justice was strongly linked to the absence of legal recognition of commercial sex activities by the state (Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017).

Increased Financial, Physical, and Sexual Violence

Evidence showed that sex workers were subjected to multiple forms of violence in all legal contexts, but this was particularly true in criminalised contexts, where restriction of measures concerning sex work brought important changes with a negative impact on the type and intensity of violence towards sex workers (INDOORS, 2014; Le Bail et al., 2019). Although sex workers experienced at least one form of violence from different perpetrators (Vanwesenbeeck, 2005), and clients were the main perpetrators of physical and sexual violence in all contexts, including regulation contexts such as Germany or The Netherlands (Aidsfonds, 2018), studies indicated that the policies adopted in criminalisation contexts had contributed to an increase in client violence towards cis and transgender sex workers (Villacampa & Tones, 2013; INDOORS, 2014; Levy, 2013; Levy et al., 2014; Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; Aidsfonds, 2018; NSWP, 2018; GAATW, 2018; Le Bail et al., 2019; Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019; Vuolajärvi, 2019; Pajnik & Radacic, 2020).

As for financial violence (e.g. being robbed, not getting paid, being financially coerced and excluded, like not being able to open a bank account or being denied labour or housing opportunities), reports showed that sex workers faced financial inequalities and exclusion in regulated and criminalised contexts, being this the most common type of violence in Finland (INDOORS, 2014). In The Netherlands, a regulated context, the main perpetrators of this type of violence were clients, banks, bosses, employers, and operators (Aidsfonds, 2018). Financial pressure would undermine sex workers’ safety at work, as sex workers, out of necessity, feel coerced to take more risks when accepting clients (Aidsfonds, 2018).

In contexts where sex workers were criminalised, like Croatia, impunity for crimes committed against sex workers has been observed since they were discouraged from reporting them (Pajnik & Radacic, 2020). Evidence showed penalising policies, such as “End demand” policies in France or The Sex Purchase Act in Sweden, increased violence risks, limiting the time sex workers had to negotiate terms of sexual transactions and choose clients (NSWP, 2018; Le Bail et al., 2019; Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019). The “End demand” law may also have given rise to more risk-seeking clients, which should affect the extent of violence against sex workers and health risks caused by unsafe practices (Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019).

Sex workers from Spain reported feeling safer in flats (Villacampa & Tones, 2013). A study found that working in clubs, window brothels, and street areas in The Netherlands offered significant protective results (Aidsfonds, 2018).

Migrant workers were even more vulnerable to violence in EU member states than national sex workers due to lack of legal status, as perpetrators often assumed that they were less likely to report crimes of violence or robbery to the police (TAMPEP, 2009).

As for the role of EU policies towards sex work in trafficking and sexual exploitation, evidence suggested that criminalisation increased the risk of sex workers being trafficked and exploited by third parties (Amnesty International, 2016; Constantinou, 2016; INDOORS, 2014; Le Bail et al., 2019; Oso, 2016; Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019; Vuolajärvi, 2019), what may constitute a situation of sexual slavery. In France, exploitation did not decrease under the criminalisation of clients (Le Bail et al., 2019). In Bulgaria, dependence on third parties caused by policing made sex workers more vulnerable to abusive situations (INDOORS, 2014). In Cyprus, a study analysing police records showed that laws aiming to end sex trafficking and prostitution led to an increase in sexual exploitation in houses and apartments and a decrease in sexual exploitation in cabarets and pubs (Constantinou, 2016). Studies also showed possible negative impacts of the Swedish Sex Purchase Act on sexual exploitation and trafficking. A drop in prices caused by the decline in demand led to decreasing in voluntary sex work, which was replaced by forced sex workers; in Sweden, the immigration and third-party regulations weakened trafficking victims’ safety: there was no way for victims of trafficking to regularise themselves, which prevented them from seeking help from officials in exploitative situations (Vuolajärvi, 2019). Regarding violence in the trafficking market, the TRANSCRIME (2005) report showed this did not seem to be strictly dependent on the legislative model on prostitution since other factors seemed to play a role, like poverty and rate of unemployment, level of welfare between countries of origin and destination, strict migration policies, level of anti-trafficking measures of the country, the entrance of new states in the EU, or cultural and linguistic similarities. According to the same report, the exploitation of victims of trafficking was equally violent outdoors and indoors, and, in some countries, like Austria or Spain, the level of indoor violence was greater.

Some violence risk reduction strategies used by cis and transgender sex workers in criminalised and regulation contexts were pretending to work with others, avoiding getting into cars or avoiding working at home (Pajnik & Radacic, 2020), avoiding leaving the city centre, hiding money, hiding occupation, always working at the same place (Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017), or using online communication to report cases of abuse or violence (NSWP, 2018).

Risks and Inequalities Related to Stigma

According to research, criminalisation reinforced stigma through discriminatory practices by institutions and the media, perpetuating and legitimising inequalities and fostering violence. Research by Jonsson and Jakobsson (2017) showed that citizens living in countries where the purchase of sex was criminalised, such as Sweden, were less tolerant towards buying sex compared to citizens living in countries where the purchase of sex was not criminalised. Also, the same study suggests that citizens living in countries where both buying sex and running a brothel were legal, like Germany and The Netherlands, were more favourable towards buying sex than citizens living in a country running a brothel was illegal, like Spain, Denmark or France.

Sex workers were the victims of institutional violence from social services, healthcare, and the Justice system, in cases like Portugal or Sweden, where being a sex worker had a strong influence, for example, in child custody decisions (Levy & Jakobsson, 2014; Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; NSWP, 2018). In contexts that criminalised sex workers, like Croatia, interviewees in the study by Pajnik and Radacic (2020) reported that stigmatised views of sex work by some assistance programs, views of sex work as violence against women, even when they experienced victimisation, or views of sex work as immoral contributed to further marginalisation and stigmatisation of their personal lives as well to being afraid to speak in public. Despite criticising moral double standards towards prostitution in Slovenia, Slovenian participants in the same study seemed less affected by stigma and keener to define their work as legitimate.

Stigmatisation also facilitated abuse against sex workers. Particularly in illegal environments, sex workers may refrain from reporting crimes committed against them due to stigma, illegality, and a climate of impunity on the clients, since often it is the sex workers themselves who end up being prosecuted (Pajnik & Radacic, 2020). In The Netherlands, where sex work was regulated, most sex workers experienced stigma (Vanwesenbeeck, 2005), and migrant sex workers from outside the EU associated greater stigma with the dominant media discourse that most sex workers were trafficking victims (Tokar et al., 2020). In Italy, reports showed that the media released news systematically stigmatising sex workers, printed reports on laws and regulations against sex work, and publicised police raids against sex workers (INDOORS, 2014).

The stigma sex workers experienced fostered self-stigmatisation and feelings of shame (Villacampa & Tones, 2013), which led them to hide their occupation from others, institutions, and their families as a protection strategy (Villacampa & Tones, 2013; Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017; AidsFonds, 2018; GAATW, 2018; Pajnik & Radacic, 2020).

Theme 3: Living and Working Conditions

Changes in Working Conditions and Spatial Displacement

Evidence showed that changes to more restrictive policies across all contexts had negative repercussions on work conditions and work displacement (Güven-Lisaniler et al., 2005; TAMPEP, 2009; Villacampa & Tones, 2013; Levy & Jakobsson, 2014; Oso, 2016; Rios-Marin, 2016; Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017; GAATW, 2018; Le Bail et al., 2019; Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019; Pajnik & Radacic, 2020; Tokar et al., 2020).

In contexts that criminalised third parties or clients, studies showed that the absence of legal recognition led to poor working conditions: although not illegal, sex work was neither recognised nor regulated as a profession (Boels, 2015; Oliveira & Fernandes, 2017; Oso, 2016).

Sex work laws worked closely with migration laws, devastatingly impacting the working conditions of migrant sex workers from outside the EU (Oso, 2016; Rios-Marin, 2016; Villacampa & Tones, 2013). Although many had legal residence permits in the countries where they work, the fact that sex work is not recognised as a formal occupation made most sex workers not eligible to apply for a legal work permit (TAMPEP, 2009). The municipal ban in Spain and the consequent absence of legal protection led migrant women from outside the EU to rely for protection on those who viewed them as a source of profit, and brothel owners and managers often threatened to report the women to the authorities. Undocumented women had no rights as citizens or workers in the EU, which increased social inequalities and decreased control over work environments across all contexts (INDOORS, 2014; Oso, 2016; Rios-Marin, 2016; TAMPEP, 2009; Villacampa & Tones, 2013). Studies also evidenced the role of the Swedish Sex Purchase Act as seemingly being used as a tool to displace public sex work (Levy & Jakobsson, 2014). In Cyprus, under the legal framework introduced in 2000, konsomatrices,Footnote 4 who initially started to work voluntarily, ended up working in conditions of servitude (Güven-Lisaniler et al., 2005).

As for most fully criminalised contexts like Lithuania or Romania, increased repression of sex work settings led to the closing of brothels, clubs, and saunas, making more women choose to work independently or shift to indoor settings to avoid police harassment, was demonstrated by the report by TAMPEP (2010). However, according to the same report, migrant women’s work conditions, mainly in illegal brothels, were also worsening. Legal norms influenced perceptions of work, and criminalisation frameworks forced sex workers to reorganise. While in Slovenia, the policy still allowed sex workers to associate with each other as a business strategy, in Croatia and Italy, any form of organising was criminalised, which led to social isolation and increased violence risks (INDOORS, 2014; Pajnik & Radacic, 2020). According to Pajnik and Radacic (2020), the criminalisation of prostitution in Croatia seriously affected street sex workers, who were targets of law enforcement agents, particularly in Zagreb. These authors have found that sex workers were often arrested and punished simply for standing in the street, while in Split, police action was undercover and targeted flats. Therefore, they argue, sex workers in both criminalisation contexts were forced to find self-organisation strategies, such as different strategies for advertising or alternative channels and ways to attract clients. In Belgium, evidence showed the lack of effectiveness of regulation and enforcement on informal activities and sex workers’ choices: given the restrictions regarding the regulation of prostitution, “back doors” were used to control the sector (Boels, 2015).

Evidence showed that policies towards sex work also influenced changes in prices across all contexts. Studies showed that in the last decade, in partial criminalisation contexts that do not criminalise sex workers, street sex workers reported a significant drop in prices due to a decline in demand, an increase in the number of sex workers, and competition (Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019; Villacampa & Tones, 2013). Conversely, in Sweden, although street sex work has suffered a drop in prices caused by the decline in demand (Levy, 2013), the price of indoor sex work increased, attracting more sex workers to the country (Levy & Jakobsson, 2014).

Finally, criminalisation policies had a detrimental effect on the relationship with clients, characterised by a shift in power relations, leaving sex workers less margin to negotiate and choose clients (Le Bail et al., 2019). In France and Sweden, sex workers’ reliance on third parties was exacerbated by legal barriers and discrimination, especially against migrant women sex workers, in renting workplaces, hotels, and apartments (NSWP, 2018).

Social Inequalities and Isolation

Research shows that the criminalisation of sex work and immigration policies increased the social inequalities that affected all sex workers in the EU, significantly impacting the lives of migrant sex workers from outside de EU (Sonnabend & Stadtmann, 2019; Villacampa & Tones, 2013). These studies conducted in partially criminalised contexts where sex workers are not criminalised showed that difficulties negotiating with clients, drop in the number of clients, and drop in prices and fines imposed by police enforcement of policies led to violence risks, economic insecurity, and financial pressure.

Third-party laws in Sweden and France had a direct and negative impact on housing, with reports of forced dislocation and evictions due to denouncements by police, often threatening landlords (Levy & Jakobsson, 2014), or being forced to ask clients to accommodate them to avoid sleeping in the streets (Le Bail et al., 2019). In practice, sex workers were pushed out of hotels and official apartment rentals, where they often felt safer, into more informal housing arrangements that could be exploitative (Vuolajärvi, 2019).

Migrant workers from outside the EU faced disproportionate inequalities and discrimination in the EU due to their precarious legal status, which caused considerable disruption in their living conditions (Boels, 2015; Güven-Lisaniler et al., 2005; Oso, 2016; Rios-Marin, 2016) and social isolation (Oso, 2016; Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017), aggravated by language barriers and lack of professional translators (Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017; TAMPEP, 2007; Tokar et al., 2020; Villacampa & Tones, 2013), risk of being reported to authorities (Oso, 2016), and spatial segregation (Rios-Marin & Torrico, 2017). In criminalised contexts, there was a general lack of comprehensive and targeted support and services for ethnic minorities, like Roma sex workers, who experienced multiple intersectional forms of discrimination (TAMPEP, 2007, 2009). The undocumented, documented, or partly legal status of migrant workers in Europe (like residence but not work permits, tourist visas but not residential permits) put them at increased risk of abuse and multiple forms of discrimination and prevented them from accessing vital services (TAMPEP, 2009). Therefore, studies showed that migrant sex workers from outside the EU living in EU countries had limited access to social welfare (Vuolajärvi, 2019) and lacked institutional support in case of victimisation and trafficking (Rios-Marin, 2016; Vuolajärvi, 2019). Lastly, studies pointed to migrant sex workers being targets of punitive regulations that were executed through immigration and third-party laws under the so-called Swedish Model and were prioritised in policing in Sweden and Finland, particularly Nigerians and other third-country nationals, which could be deported or be denied entry to the country (Vuolajärvi, 2019). In Cyprus, migrant sex workers were taken directly from the airport to a hospital to be tested for STIs, including HIV/AIDS, syphilis, and gonorrhoea. Having a positive result led to immediate deportation, and if the tests were negative, it was granted a work permit (Güven-Lisaniler et al., 2005). The legal framework (immigration law) was one of the leading causes of the vulnerability of migrant sex workers from outside the EU across all contexts (TAMPEP, 2010; Vuolajärvi, 2019).

Finally, according to the research, sex workers used multiple strategies to face inequalities and social isolation, like connecting with family, friends, and colleagues (INDOORS, 2014). NGOs had a positive impact on the living conditions of sex workers in multiple legal contexts, providing confidential psychosocial and legal support, information in the native language of migrant workers, harm reduction strategies, counselling, and protection in case of trafficking (Germany) as well as training to recognise human trafficking situations (GAATW, 2018).

Discussion

This review aimed to synthesise the evidence available and grey literature that studied associations between EU policies towards sex work and the health, safety, and living and working conditions of sex workers in EU countries.

The evidence demonstrated that criminalisation and regulation of any form of sex work had vast consequences on the lives of sex workers who live in the twenty-five EU member states included in this review, in terms of healthcare, prevalence and risk of contracting HIV and STIs, stigmatisation and discrimination, financial, physical, and sexual victimisation due to marked social inequalities, for both nationals and migrants from outside the EU. Furthermore, evidence showed a “domino effect”, by which the harm caused by policies in each one of the analysed dimensions (health, safety, and living and working conditions) influences all of them, emphasising the need to create comprehensive policies to protect and better respond to the contextual factors shaping sex workers’ marginalisation, in accordance to the goals and values of the European Union of human dignity, respect for individual freedom, equality, the rule of law, and human rights (Treaty of Lisbon, 2007).

As confirmed by previous research in other countries (Shannon et al., 2015; Platt et al., 2018; Reynish et al., 2021), the included literature strongly suggested that the removal of criminal laws and enforcement against sex workers and clients may bring the most significant benefit to sex workers and society in general, allowing them to enter the formal economy and benefit from social insurance, protection from law enforcement and access to Justice system, fostering empowerment, better mental and physical health, and reducing HIV prevalence, vulnerability to stigma, and physical and sexual exploitation.

Evidence showed that inequities in accessing healthcare within the EU persisted among sex workers, pointing out that stigma and discrimination as the most prominent barriers that prevented or discouraged sex workers from accessing and seeking health services as a direct consequence of discrimination by health professionals and institutions. In addition, stigma, including internalised stigma, contributed to sex workers avoiding seeking healthcare services, sometimes resorting to self-care practices. These results are in line with previous studies that showed social stigmatisation of sex work has a negative impact on healthcare provision and that stigma attached to sex work is prevalent in healthcare settings (Bowen & Bungay, 2016; Ma et al., 2017; Platt et al., 2018; Reynish et al., 2021). Moreover, sex workers experience almost triple the barriers the general population encounters in accessing healthcare (Benoit et al., 2018).

Evidence also confirmed that restrictive measures towards sex work in the EU, even in regulatory contexts, played an essential role in the physical health of sex workers, also reflected in a greater prevalence of HIV and STIs, whether through increased exposure to violence by police and clients, lack of health insurance, economic pressure and occupational risks, or ineffective and selective harm reduction strategies, like forced testing, as in other parts of the globe (Erausquin et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2017; Platt et al., 2018; Shannon et al., 2015). Self-determination and control have been shown to have a positive impact on HIV prevalence and risk, as well as on general health, emotional health, and well-being, something that is missing under repressive regimes (Platt et al., 2018; Vanwesenbeeck, 2001).

The included studies that focused on sex workers’ mental health (Krumrei-Mancuso, 2017; Vanwesenbeeck, 2005) found that poor mental health was related to structural and social factors like violence, labour vulnerabilities, social inequalities, and stigma, in line with previous literature (Corrigan, 2004; Macioti et al., 2017),Footnote 5 contradicting the idea that sex work is intrinsically harmful, as characterised by previous research. Such research has been criticised methodologically for selecting vulnerable samples and ignoring data that did not comply with its authors’ views and assumptions (Weitzer, 2005).

In turn, according to our research, criminalisation of sex work also reinforces stigma, either through fostering citizen’s stigmatised views of sex workers through the media as victims or villains, legitimising inequalities through institutions, from social services to the Justice system, which, having the responsibility to enforce restrictive laws, end up acting accordingly, as in the case with child custody decisions, as supported by previous evidence (Bowen & Bungay, 2016; Platt et al., 2018).

The included literature evidenced that sex workers were subject to multiple forms of violence in all legal contexts, including financial, sexual, and physical violence, assuming significant proportions in the context of criminalisation. Studies have shown that the criminalisation of sex work and stigma interacted in ways that generated and increased physical and sexual violence in these workers due to abuses committed by the police and by their clients, who took advantage of fear, economic pressure, less time to negotiate, and the fact that there may not be denouncements or resistance, fostering a climate of impunity (Deering et al., 2014; Platt et al., 2018). Although street settings were considered riskier, our synthesis concluded that in indoor contexts, multiple nuances have to be considered, like the possibility of exploitation by operators (Pitcher & Wijers, 2014). Previous research on a decriminalised context has revealed that, although violence has not decreased significantly, sex workers know they will be protected because it is their legal right (Abel et al., 2010).

Research in all 25 EU countries included in this review revealed that policy and legislative changes on all levels had negative consequences for migrants from outside the EU and national sex workers, despite the improvements in this matter for migrant sex workers from the more recent EU countries. Even in partially criminalised (excluding the criminalisation of sex workers) and regulatory contexts, like Spain and The Netherlands, the increasingly restrictive measures at a municipal level seemed to complement central government policies, with evident practical consequences in the lives of sex workers, including spatial displacement and increased violence risks, leading to a de facto criminalisation that revealed states’ double standards and ineffectiveness. That said, studies showed the need for a new progressive legal framework regarding sex work, which integrates national and municipal or provincial laws and focuses on the complete protection of sex workers in all analysed dimensions.

In all contexts, the conflation between sex work policies and immigration policies led to a double standard that affected mainly migrants coming from outside the EU, and this is particularly harmful since a large portion of sex workers are in this situation, leaving them outside the scope of the legal system, and with few alternatives other than hiding from the authorities and submitting to situations of exploitation that they will not be able to later denounce, given the real possibility of being arrested and deported. Policies on migration and sex work in Spain, for example, have led to an increase in undocumented female migrants from outside the EU and considerable deterioration of their working and living conditions.

A growing number of EU member states are now turning to criminalise the purchase of sex, adopting the so-called Swedish Model, based on the idea that “ending demand” will ultimately abolish sex work and is, therefore, an abolitionist in nature (Vanwesenbeeck, 2017). Evidence showed that the Swedish Model, although applied inconsistently in Sweden, Finland, France, and Ireland, replicated inequalities in the regulation of commercial sex through prostitution and immigration legislation, leading to destructive consequences in the safety and integrity of sex workers, which have been overlooked. According to the included literature, this “dual regulation” led to a double standard, visible in service provision, that excluded migrants without permanent residence permits (Vuolajärvi, 2019). This legislation, introduced to eradicate prostitution, viewed as a form of gender and sexual violence, successfully increased the stigma towards sex work, which has been proven by research to have negative impacts on the mental and physical health of sex workers and detrimental effects on their living and working conditions and safety (Vanwesenbeeck, 2017). Furthermore, no evidence was found demonstrating that the Swedish Sex Purchase Act has succeeded in decreasing levels of prostitution (Jordan, 2012; Levy & Jakobsson, 2014), but there was evidence that showed that it caused spatial displacement, social problems, and changes in the type of relationships with clients with increased risks for sex workers, without putting in practice effective strategies of harm reduction and condom distribution (Jordan, 2012; Vanwesenbeeck, 2017). Evidence also showed that the criminalisation of buying sexual services increased sexual slavery under certain conditions and recommended avoiding regulatory measures that trigger a fall in prices. Finally, findings showed that the “Swedish Model” and its anti-trafficking measures have also displaced commercial sex acts. Despite the release of campaigns around human sex trafficking in Sweden, research showed that migrant trafficking victims were not given appropriate social support, something that kept them from reporting crimes related to trafficking out of, once again, justifiable fears of being deported.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This review aimed to synthesise the evidence available regarding sex workers’ health, safety, and living and working conditions across EU member states, which is critical to informing evidence-based policymaking and practice.

The findings evinced that removing any criminal laws and enforcement against sex workers, clients, and third parties could significantly improve sex workers’ physical and mental health, safety, and living and working conditions across the 25 member states included in this review. The removal of these laws and sanctions may bring the most significant benefit to sex workers and society in general, allowing them to enter the formal economy and benefit from social insurance, protection from law enforcement and access to the Justice system, fostering empowerment, better mental and physical health, and reducing vulnerability to stigma, HIV prevalence, and physical and sexual exploitation.

There is a need for structural changes in policing and legislation that focus on labour and legal rights, social and financial inequities, human rights, and stigma and discrimination to protect cis, transgender sex workers and ethnical minorities in greater commitment to reduce sex workers’ social inequalities, exclusion, and lack of institutional support. These measures could also positively impact reducing and monitoring human trafficking and exploitation.

The evidence makes a strong case for fully decriminalising adult consensual sex work. Decriminalisation has been considered the best model, including for protecting the health and well-being of sex workers (Macioti et al., 2022), enhancing their access to services and justice (Platt et al., 2018), making the industry safer, and improving human rights of sex workers within all sectors of the sex industry (Abel, 2014). Belgium has adopted it recently, becoming the first country in Europe to do so, and all sound evidence in other countries proves significant improvements since decriminalisation (Abel, 2014; Macioti et al., 2022).

More qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research that focuses specifically on how EU policies affect sex workers at municipal and national levels and what factors contribute to increasing trafficking and exploitation concerning these policies is needed. This research should consider the diversity and intersectionality among sex workers to inform evidence-based and inclusive policies since ideological research will only perpetuate moral politics (Lakoff, 2002). Legal reforms need to be strictly evidence-based, not driven by unsubstantiated, exaggerated, or sensationalised claims or fears (Paez, 2017) because otherwise, policies about sex work can best be understood as an instance of morality politics (Hong et al., 2018).

Finally, it is crucial that relevant stakeholders, like sex workers, clients, or proprietors, participate in the implementation and design of new and more comprehensive policy measures (Wagenaar & Altink, 2012). Destigmatisation is only possible with the participation of those with lived experiences of stigma in developing progressive laws, policies, and practices (Benoit et al., 2018; Vanwesenbeeck, 2017).

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

As can be seen in Table 3, some studies included more than one country with different legal frameworks.

Prostitution in Romania was removed from the Criminal Code in 2014 (Reinschmidt, 2016; Romania Criminal Code, 2014). Since then, sex workers can be sanctioned with vagrancy and other public order laws (Institute of Development Studies, n.d.), and prostitution has been regarded as an administrative offence, being subjected to a fine (Reinschmidt, 2016). If the fine is not paid, sex workers must fulfil community service or an alternative term of imprisonment (Romania Criminal Code, 2014). Also, it is illegal to facilitate prostitution or obtain economic benefits from it (Romania Criminal Code, 2014). The legal text distinguishes between prostitution as a means of main subsistence and satisfaction of basic needs and a practice aimed at increasing income (Danet, 2018). In the first case, prostitution is not criminalised but fined (Danet, 2018). The second situation is excluded from the legal category of prostitution, is not referenced in the Criminal Code, and is neither fined nor criminalised (Barbu, 2013).

The Sex Purchase Act is a law implemented in Sweden in 1999 criminalising the purchase of sexual services. Under this law, it is illegal to buy sex but not to sell it.

According to Güven-Lisaniler et al. (2005), in legal terms, konsomatrices are women paid to eat and drink with clients at a nightclub and are not allowed to practice prostitution. However, the authors add, they regularly engage in sex acts in exchange for money on the nightclub premises and outside. In the same article, Güven-Lisaniler et al. also clearly explain the characteristics of this servitude, which they call indentured servitude.

Although it was not included in this research because it was published only in 2021, the study by Macioti et al. (2021) on access to mental health services for people who sell sex in Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the UK refers to the years 2016 to 2018, which is within the scope of this review. Thus, it is worth mentioning that the results of this study are in line with the results of the present research, including that working in criminalised conditions is highly detrimental to sex workers’ mental health and that there is a positive relationship between experiences of isolation, stigma, lack of access to quality mental health support and peer networks, and the criminalisation of sex work or sex work-related activities.

References

Abel, G. M. (2014). A decade of decriminalisation: Sex work ‘down under’ but not underground. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 14(5), 580–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895814523024

Abel, G., Fitzgerald, L., Healy, C., & Taylor, A. (Eds.) (2010). Taking the crime out of sex work: New Zealand sex workers’ fight for decriminalisation. Policy Press.

AidsFonds. (2018). Sex work, stigma and violence in the Netherlands. https://www.nswp.org/resource/sex-work-stigma-and-violence-the-netherlands

Amnesty International. (2016). Amnesty International Policy on state obligations to respect, protect and fulfill the human rights of sex workers. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol30/4062/2016/en/

Armstrong, L. (2017). From law enforcement to protection? Interactions between sex workers and Police in a decriminalized street-based sex industry. The British Journal of Criminology, 57(3), 570–588. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw019

Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds). (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

Bennachie, C., Pickering, A., Lee, J., Macioti, P., Mai, N., Fehrenbacher, A., Giametta, C., Hoefinger, H., & Musto, J. (2021). Unfinished decriminalisation: The impact of section 19 of the Prostitution Reform Act 2003 on migrant sex workers’ rights and lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Sciences, 10(5), 179.https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050179

Benoit, C., Jansson, M., Smith, M., & Flagg, J. (2018). Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4/5), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652

Boels, D. (2015). The challenges of Belgian prostitution markets as legal informal economies: An empirical look behind the scenes at the oldest profession in the world. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 21(4), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-014-9260-8

Bowen, R., & Bungay, V. (2016). Taint: An examination of the lived experiences of stigma and its lingering effects for eight sex industry experts. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(2), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1072875

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications.

Barbu, I. A. (2013). Main consideration about the physical element (Actus Reus) in what regards the act of prostitution. Public Security Studies, 2(1), 67–71.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2001). Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews (Report n. º 4). https://www.york.ac.uk/crd/guidance/s

Constantinou, A. (2016). Is crime displacement inevitable? Lessons from the enforcement of laws against prostitution-related human trafficking in Cyprus. European Journal of Criminology, 13(2), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370815617190

Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

Danet, A. (2018). Romania. In H. Wagenaar & S. Jahnsen (Eds.), Assessing prostitution policies in Europe (pp. 258–271). Routledge Press.

Deering, K., Amin, A., Shoveller, J., Nesbitt, A., Garcia-Moreno, C., Duff, P., Argento, E., & Shannon,. (2014). A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. American Journal of Public Health, 104(5), e42–e54. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301909

Erausquin, J., Reed, E., & Blankenship, K. (2011). Police-related experiences and HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh. India. the Journal of Infectious Diseases, 204(5), S1223–S1228. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir539

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

Footer, K. H., Silberzahn, B. E., Tormohlen, K. N., & Sherman, S. G. (2016). Policing practices as a structural determinant for HIV among sex workers: A systematic review of empirical findings. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 19(4 Suppl 3), 20883. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.19.4.20883

Frantzen, K., & Fetters, M. D. (2016). Meta-integration for synthesizing data in a systematic mixed studies review: Insights from research on autism spectrum disorder. Quality and Quantity, 50(5), 2251–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0261-6

Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women. (2018). Sex workers organising for change: Self-representation, community mobilisation, and working conditions: Spain. https://gaatw.org/publications/SWorganising/Spain-web.pdf

Global Network of Sex Work Projects. (2018). The impact of ‘end demand’ legislation on women sex workers. https://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/pb_impact_of_end_demand_on_women_sws_nswp_-_2018.pdf

Güven-Lisaniler, F., Rodríguez, L., & Uğural, S. (2005). Migrant sex workers and state regulation in North Cyprus. Women’s Studies International Forum, 28(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2005.02.006

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

Immordino, G., & Russo, F. (2015). Regulating prostitution: A health risk approach. Journal of Public Economics, 121, 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.11.001

INDOORS. (2014). Outreach in indoor sex work settings 2013–2014: A report based on the mapping of the indoor sex work sector in nine European cities. https://apdes.pt/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Outreach-in-Indoor-Sex-Work-Settings-Report.pdf

Institute of Development Studies (n.d.). Sex work law. Sexuality, poverty and law programme. http://spl.ids.ac.uk/sexworklaw

Jonsson, S., & Jakobsson, N. (2017). Is buying sex morally wrong? Comparing attitudes toward prostitution using individual-level data across eight Western European countries. Womens Studies International Forum, 61, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2016.12.007

Jordan, A. (2012). The Swedish law to criminalize clients: A failed experiment in social engineering. Issue 4. Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Law. American University – Washington College of Law. https://rb.gy/wqsoj4

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J. (2017). Sex work and mental health: A study of women in the Netherlands. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1843–1856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0785-4

Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral politics: How liberals and conservatives think (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

Le Bail, H., Giametta, C., & Rassouw, N. (2019). What do sex workers think about the French Prostitution Act? A study on the impact of the law. Médecins du Monde, 96 pp. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02115877

Lemos, A. & Oliveira, A. (2021). Understanding the impact of UE prostitution policies on sex workers: A mixed study systematic review. PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021236624. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021236624

Levy, J. (2013). Swedish abolitionism as violence against women. Sex Worker Open University, Sex Workers’ Rights Festival Glasgow. https://www.swarmcollective.org/briefing-documents-publications

Levy, J., & Jakobsson, P. (2014). Sweden’s abolitionist discourse and law: Effects on the dynamics of Swedish sex work and on the lives of Sweden’s sex workers. Criminology & Criminal Justice: An International Journal, 14(5), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895814528926

Lizarondo, L., Stern, C., Carrier, J., Godfrey, C., Rieger, K., Salmond, S., & Loveday, H. (2020). Mixed methods systematic reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI, 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-09

Ma, P., Chan, Z., & Loke, A. (2017). The socio-ecological model approach to understanding barriers and facilitators to the accessing of health services by sex workers: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 21(8), 2412–2438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1818-2

Macioti, P. G. & Geymonat, G. G. (2016). Sex workers speak. Who listens? Open Democracy.

Macioti, P. G., Geymonat, G. G., & Mai, N. (2021). Sex work and mental health. Access to mental health services for people who sell sex in Germany, Italy, Sweden and UK. https://doi.org/10.26181/612eef8a702b8

Macioti, P. G., Grenfell, P., & Platt, L. (2017). Sex work and mental health. University of Leicester.

Macioti, P. G., Power, J., & Bourne, A. (2022). The health and well-being of sex workers in decriminalised contexts: A scoping review. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00779-8

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Guidelines and Guidance Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: THe PRISMA Statement. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., & Aromataris, E. (2014). Data extraction and synthesis: The steps following study selection in a systematic review. American Journal of Nursing, 114(7), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000451683.66447.89

Oliveira, A. & Fernandes, L. (2017). Sex workers and public health: Intersections, vulnerabilities and resistance. Salud Colectiva, 13(2), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.18294/sc.2017.1205

Oliveira, A., Lemos, A., Mota, M., & Pinto, R. (2020). Less equal than others: The laws affecting sex work, and advocacy in the European Union. University of Porto/The Left (Group of the European Parliament).

Oso, L. (2016). Transnational social mobility strategies and quality of work among Latin-American women sex workers in Spain. Sociological Research Online, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.4129

Östergren, P. (2017). From zero-tolerance to full integration: Rethinking prostitution policies. DemandAT Working Paper No. 10. https://www.demandat.eu/publications/zero-tolerance-full-integration-rethinking-prostitution-policies

Outshoorn, J. (2018). European union and prostitution policy. In H. Wagenaar & S. Jahnsen (Eds.), Assessing prostitution policies in Europe (pp. 363–375). Routledge.

Paez, A. (2017). Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 10(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12266

Pajnik, M. & Radacic, I. (2020). Organisational patterns of sex work and the effects of the policy framework. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, (1868–9884). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00482-6

Pitcher, J., & Wijers, M. (2014). The impact of different regulatory models on the labour conditions, safety and welfare of indoor-based sex workers. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 14(5), 549–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895814531967

Platt, L., Grenfell, P., Meiksin, R., Elmes, J., Sherman, S. G., Sanders, T., & Crago, A. -L. (2018) Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Med, 15(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002680

Pluye, P., & Hong, Q. N. (2014). Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440

Pluye, P., Robert, E., Cargo, M., Bartlett, G., O’Cathain, A., Griffiths, F., Boardman, F., Gagnon, M. P., & Rousseau, M. C. (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Retrieved from http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com

Reeves, A., Steele, S., Stuckler, D., McKee, M., Amato-Gauci, A., & Semenza, J. C. (2017). National sex work policy and HIV prevalence among sex workers: An ecological regression analysis of 27 European countries. Lancet Hiv, 4(3), E134–E140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30217-X

Reinschmidt, L. (2016). Regulation of prostitution in Bulgaria, Romania and the Czech Republic. Observatory for Sociopolitical Developments in Europe. https://beobachtungsstelle-gesellschaftspolitik.de/f/958037694b.pdf

Reynish, T., Hoang, H., Bridgman, H., & Easpaig, B. N. G. (2021). Barriers and enablers to sex workers’ uptake of mental healthcare: A systematic literature review. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 18, 184–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00448-8

Rios-Marin, A. (2016). Working in the sex industry: A survival strategy against the crisis? Revista Internacional de Estudios Migratorios, 6(2), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.25115/riem.v6i2.424

Rios-Marin, A. & Torrico, M. G. -C. (2017). Sex work and social inequalities in the health of foreign migrant women in Almeria, Spain. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 58, 54–67. http://hdl.handle.net/10396/15958

Romania Criminal Code (2014). https://www.legislationline.org/download/id/8291/file/Romania_Penal%20Code_am2017_en.pdf

Sex Workers’ Rights Advocacy Network. (2009). Arrest the violence: Human rights abuses against sex workers in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/arrest-violence-human-rights-violations-against-sex-workers-11-countries-central-and-eastern

Shannon, K., Strathdee, S., Goldenberg, S., Duff, P., Mwangi, P., Rusakova, … & Boily, M-C. (2015). Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. The Lancet, 385(9962), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4

Sonnabend, H., & Stadtmann, G. (2019). Good intentions and unintended evil? Adverse effects of criminalizing clients in paid sex markets. Feminist Economics, 25(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1644454

TAMPEP. (2007). Gap analysis of service provision to sex workers in Europe 2. https://tampep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Gap-Analysis-of-Service-Provision-to-Sex-Workers.pdf

TAMPEP. (2009). Sex work in Europe: A mapping of the prostitution scene in 25 European countries. https://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/TAMPEP%202009%20European%20Mapping%20Report.pd

TAMPEP. (2010). National mapping reports. https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/chafea_pdb/assets/files/pdb/2006344/2006344_d4_deliverable_t8_annex_10_d_national_reports_mapping.pdf

TAMPEP. (2015). TAMPEP on the situation of national and migrant sex workers in Europe today. https://tampep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/TAMPEP-paper-2015_08.pdf

Tokar, A., Osborne, J., Hengeveld, R., Lazarus, J. V., & Broerse, J. E. W. (2020). ‘I don’t want anyone to know’: Experiences of obtaining access to HIV testing by Eastern European, non-European Union sex workers in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0234551. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234551

TRANSCRIME. (2005). Study on national legislation on prostitution and the trafficking in women and children. https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/publications/study-national-legislation-prostitution-and-trafficking-women-and-children_en

Treaty of Lisbon. (2007). Treaty of Lisbon, amending the treaty on European Union and the treaty establishing the European community, 13 December 2007, 2007/C 306/01. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:12016ME/TXT&from=EN