Abstract

Introduction

Online dating is widespread among young adults, and particularly young sexual minority men. Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD), also known as “sexual racism,” is frequently reported to occur within these digital spaces and may negatively impact the psychological wellbeing of young sexual minority Black men (YSMBM). However, the association between RSD and psychological wellbeing is not well understood.

Methods

Using data (collected between July 2017–January 2018) from a cross-sectional web-survey of YSMBM (N = 603), six multivariable regression models were estimated to examine the association between five RSD subscales and depressive symptoms and feelings of self-worth. RSD subscales were derived from the first preliminarily validated scale of sexual racism.

Results

Analyses revealed that White superiority (β = .10, p < .01), same-race rejection (β = .16, p < .001), and White physical objectification (β = .14, p < .01) were all significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms, and White physical objectification (β = -.11, p < .01) was significantly associated with lower feelings of self-worth.

Conclusions

This study is among the first to examine the relationship between multiple, distinct manifestations of RSD and depressive symptoms and self-worth using quantitative analyses and provides evidence that RSD is negatively associated with psychological wellbeing.

Policy Implications

Site administrators should institute robust anti-racism policies on their platforms and hold users accountable for discriminatory behavior. Activists may also consider forming coalitions and/or developing campaigns to bring about greater awareness of RSD, in an effort to influence site administrators to enact policy change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies examining the health needs of young Black sexual minority men (YSMBM) have predominantly focused on the disproportionate rates of HIV among this population. This focus comes at the expense of other critical health domains, such as discrimination and psychological wellbeing, as there is a noteworthy deficit of studies focusing on these topics as it pertains to YSMBM (Graham et al., 2011; Wade & Harper, 2017). One potentially relevant area related to the health and functioning of YSMBM is the phenomenon of racialized sexual discrimination (RSD). RSD, often referred to as sexual racism, is a unique and understudied phenomenon in the social science and health literature (Wade & Harper, 2020a). RSD is defined as the sexualized discriminatory treatment that sexual minority men of color experience when seeking partners for an intimate encounter. While RSD may occur in person, this phenomenon is most often discussed in the context of online partner-seeking, which is widespread among young sexual minority men (Badal et al., 2018; Meanley et al., 2020; Paz-Bailey et al., 2017). In one study, researchers reported that sexual minority men used a dating app to meet intimate partners 22 times per week on average (compared to 8 times per week for heterosexual men), and 55% of LGB adults reported having used a website/mobile app for online dating in a recent poll (Grov et al., 2014; Pew Research Center, 2020). Given the pervasiveness of online partner-seeking, the deficit of empirical research on RSD is alarming, as seeking and forming intimate connections is a high priority among young sexual minority men (Bauermeister et al., 2009; Frost et al., 2008; Golub et al., 2012; Slavin, 2009). Researchers have reported that sexualized discriminatory treatment directed toward racial/ethnic minorities on gay apps and websites is widespread, is often perpetuated by White users, and takes a variety of different forms—ranging from exclusion and rejection, to degradation and erotic objectification (Callander et al., 2012, 2015; McKeown et al., 2010; Paul et al., 2010; Robinson, 2015; Wade & Harper, 2020a, b; White et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2009; Winder & Lea, 2019).

Overwhelmingly, researchers point to a dominant theme in the social discourse surrounding RSD—that selecting a partner based on their racial/ethnic features simply represents a “personal preference” and is neither a racist act nor reflective of racist attitudes (Callander et al., 2012, 2015; Robinson, 2015). This sentiment, researchers note, is most often expressed by White men within these spaces. Furthermore, Whiteness appears to be the baseline for sexual attractiveness in US and Eurocentric cultures and is often the standard by which desirability is measured (Campón & Carter, 2015; Jha, 2015; Reece, 2016; Robinson, 2015). This sexualized White superiority is pervasive on gay dating apps and websites and is represented by exclusionary preferences (e.g., a White person indicating that they do not want to be with a Black person), inclusionary preferences (e.g., a White person indicating that they only want to date other White people), degradation (e.g., White people making denigrating comments about racial/ethnic minorities on their dating profiles, and/or during a conversation), and expressions of desire for White-centric physical features (Wade & Harper, 2021). White superiority is even perpetuated by people of color (POC) indicating that they are not interested in someone of their own race and instead expressing inclusionary preferences for White people. While White superiority has been documented in the literature exploring RSD (Wade & Harper, 2020a, 2021), researchers have yet to systematically evaluate the ways in which White superiority affects YSMBM in the context of intimate partner seeking, especially as it relates to their psychological health. YSMBM who regularly use mobile apps and websites to meet sex partners may be at elevated risk for poor psychological health outcomes after repeated exposure to such discriminatory experiences.

Another common form of RSD is experiencing rejection, after attempting to engage with another user online. In these instances, YSMBM may be told explicitly by another user that the user is not interested in meeting them because of their race/ethnicity. Alternatively, the user may simply ignore the message—presumably because of the young man’s race/ethnicity. Many racial/ethnic minority men report being frequently ignored by other users—who are often White—and attribute this lack of response to the fact that they are a person of color (McKeown et al., 2010). However, YSMBM may also be rejected in the same manner by members of their own racial/ethnic group. While there is less research on how RSD may be perpetuated by POC toward other POC, researchers in a recent study reported that POC to POC discrimination not only occurred, but was a particularly salient experience for many participants (Wade & Harper, 2020b). Such cases may be indicative of possible internalized racism on the part of those who perpetuate such discrimination.

There has been considerable discussion in the social science and health literature about internalized racism and appropriated racial oppression—where members of an ethnic group hold negative perceptions of their own race/ethnicity, devalue their own group membership, and favor White/Eurocentric beauty standards (Campón & Carter, 2015; Cokley, 2002; Hughes et al., 2015; Lipsky, 1987; Pyke, 2010; Tappan, 2006). Researchers have also reported that internalized racism has a positive association with depressive symptoms and other markers of psychological distress among Black Americans—and among a sample of Black LGBQ individuals, internalized racism had a negative association with self-esteem (Molina & James, 2016; Mouzon & McLean, 2017; Szymanski & Gupta, 2009). Internalized racism may indeed be reflected in instances where YSMBM ignore or reject other YSMBM, and the researchers note that experiences of same race or of other POC rejection may represent a distinct form of RSD that can also contribute to negative health outcomes. As such, discrimination by POC directed toward other POC should not be overlooked in the context of RSD and should be a focal point for investigators who study this phenomenon.

While White superiority and rejection are among the most commonly reported themes in the literature, they are not the only manifestations of RSD. Many researchers have reported that the eroticization/objectification of YSMBM are also common experiences among this population. In these instances, YSMBM may be objectified for the exoticism of their phenotypic traits (e.g., dark skin color) or stereotypes about their anatomy (e.g., Black men have larger penises) (Plummer, 2007; Wilson et al., 2009). Researchers have reported that men who experience this eroticization consider it to be just as upsetting as being rejected from users, or being subject to White superiority experiences, even though men desiring them for their physical traits may improve their opportunities for a sexual encounter (McKeown et al., 2010; Paul et al., 2010). YSMBM can also be objectified on the basis of their physical traits by members of their own race, which adds an additional layer of complexity to the phenomenon of RSD. POC objectification of POC is perhaps the most limited area of RSD research; thus, accounting for this particular experience of RSD will be important to fully understand the phenomenon.

Stress and Psychological Wellbeing

Minority stress theory (MST; Meyer, 1995, 2003) and intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1990) are especially useful frameworks for contextualizing the ways in which RSD may negatively impact the psychological wellbeing of YSMBM. MST posits that experiencing stigma and discrimination based on one’s minority identity places minority groups (particularly sexual minorities) at heightened risk for poor psychosocial functioning. Intersectionality posits that a single determinant of identity is insufficient to capture the full breadth of experiences that marginalized people face. Rather, the combination of multiple stigmatized identities results in a complex set of characteristics and experiences that may predispose certain populations to unique health risks. MST and intersectionality have been widely applied in research investigating the associations between stress/discrimination and adverse psychological health outcomes among sexual minority men of color (Balsam et al., 2011; Bowleg, 2013; Cyrus, 2017; Schmitz et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2014). In a recent study, researchers reported that racial discrimination was associated not only with elevated rates of depression, but also suicidal ideation, among a large sample of Black men in the USA (Goodwill et al., 2019). Many researchers have also reported that gay/bisexual Black men have high rates of depressive symptoms, and many appear to be at elevated risk for suicide (Hightow-Weidman et al., 2011; Magnus et al., 2010; Meyer, 2003; O’Donnell et al., 2011; Wohl, et al., 2011). This population is often subject to a disproportionate amount of microaggressions and social stressors in their daily lives, including homophobia, heteronormativity, racism, community stigma/racism, and high rates of HIV infection (Arnold et al., 2014; Harper & Wilson, 2016; Jamil et al., 2009; Loiacano, 1989; O’Donnell et al., 2011; Wilson & Harper, 2013). There is limited research, however, on the experiences of adolescent and young adult gay/bisexual Black men, as it pertains to both discrimination and indicators of psychological health, such as depression (Wade & Harper, 2017). By extension, the specific phenomenon of RSD, and its association with depressive symptomatology among this population, is not well understood. As such, there is a demonstrable need to examine these associations, in order to develop appropriate health interventions for this population.

In addition to outcomes such as depressive symptomatology, positive self-affirmations are an important component of a holistic understanding of mental health (Critcher & Dunning, 2015; Sherman & Cohen, 2006; Steele, 1988). Positive self-affirmations often include outcomes such as self-worth and self-esteem. Researchers have reported that racism may be associated with a reduced sense of self-esteem among racial/ethnic minorities and gay and bisexual men of color and may also be associated with other poor psychological health outcomes (Diaz et al., 2001; Huebner et al., 2004; Schmitt et al., 2014; Verkuyten, 1998). While self-worth and self-esteem have been studied extensively in the health literature, there is limited research on these outcomes among YSMBM (Wade & Harper, 2017). Moreover, research examining the association between RSD and positive self-affirmation outcomes are exceedingly sparse, with only minimally generalizable inferences drawn from qualitative research on the phenomenon (Paul et al., 2010).

Contributing Factors to Psychological Health in Online Partner Seeking

In the context of online partner seeking, it is also necessary to consider factors other than racial discrimination that may be associated with poor psychological health among this population. First and foremost, it is essential to account for the amount of time users spend looking for partners online, given that the more time users spend online, the more opportunities they have to encounter instances of racism. Second, in an atmosphere where rejection (whether RSD-driven or not) is commonplace, it is important to account for individuals’ general sensitivity to rejection. Perceived rejection is associated with greater depressive symptoms and may be especially salient when it occurs in intimate partner contexts (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Nolan et al., 2003). Other basic sociodemographic factors, such as age, educational attainment, and relationship status, may also be important to account for. For relationship status in particular, it is unclear whether or not having a primary partner has any association with RSD. However, researchers have noted that gay men in romantic relationships experience greater psychological wellbeing, and that men in open relationships often discuss their external partner-seeking experiences with their primary partners (Mogilski et al., 2015; Parsons et al., 2013). It is possible, then, that having the security of a primary partner may account for some of the variance in psychological health outcomes in the context of seeking external partners for a sexual encounter.

In addition to the factors listed above, self-perceived sexual attractiveness (SPSA) may also be a critical factor to consider when examining psychological health among YSMBM who seek sexual partners online. SPSA, researchers note, is distinct from general perceptions about one’s physical attractiveness and is therefore a particularly relevant construct when negotiating the possibility of a sexual encounter (Wade, 2000). Among the general population, researchers have reported that positive perceptions of one’s own sexual attractiveness are associated with indicators of psychological wellbeing, such as self-esteem (Amos & McCabe, 2017; Bale & Archer, 2013). Among sexual minority populations, SPSA specifically has been largely under-investigated, but body image and other appearance-related concerns are widely reported and associated with greater depressive symptoms relative to heterosexual populations (Dahlenburg et al., 2020; Ehlinger & Blashill, 2016). There is an even larger deficit of literature on SPSA and body image concerns as it relates to sexual minority men of color. However, researchers in one recent study investigated the complex ways in which sexual minority men of color negotiate racialized body ideals and highlighted how negative perceptions of one’s physical attractiveness may be associated with poor psychosocial functioning outcomes, such as disordered eating and self-esteem (Brennan et al., 2013). Given the centrality of SPSA in social venues where men are looking to find partners for sex, this is yet another important variable to account for when investigating the potential effects of RSD.

The Racialized Sexual Discrimination Scale

In a recent study, researchers tested a comprehensive and multidimensional scale of RSD, and the scale was found to be reliable with sound psychometric properties (Wade & Harper, 2021). This scale aims to capture the complete spectrum of RSD experiences and measures both the effect of an RSD experience and the frequency with which a given RSD experience is encountered. Together, the product of the effect and frequency ratings of a given RSD experience represents the overall impact of that experience. The purpose of the RSD scale is to examine the association between discriminatory experiences online and a variety of behavioral health outcomes, including markers of psychological wellbeing. Only a handful of studies to date have investigated these associations quantitatively. While these studies suggest that RSD is negatively associated with psychological health, the majority have not used validated scales, and existing measures do not capture the unique aspects of RSD that happen exclusively in online settings (Bhambhani et al., 2020; Hidalgo et al., 2020; Thai, 2020).

Given the recent creation of an RSD scale, the current study aims to explore the relationship between RSD and markers of psychological wellbeing among a sample of YSMBM. Specifically, we examined the association between rejection, objectification, and White superiority on two different psychological health outcomes (depressive symptoms and self-worth). Based on a review of the literature, and using minority stress theory, we hypothesized that higher scores on RSD experiences would be associated with an increase in depressive symptoms and a decrease in feelings of self-worth for study participants.

Method

Participants

Eligibility Criteria

In order to be eligible for the study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (1) identify as a man; (2) be assigned male sex at birth; (3) identify primarily as Black, African American, or with any other racial/ethnic identity across the African diaspora (e.g., Afro-Caribbean, African, etc.); (4) be between the ages of 18 and 29 inclusive; (5) identify as gay, bisexual, queer, same-gender-loving, or another non-heterosexual identity, or report having had any sexual contact with a man in the last 3 months; (6) report having used a website or mobile app to find male partners for sexual activity in the last 3 months; and (7) reside in the USA.

Recruitment

A non-probability convenience sample of YSMBM was recruited using best practices for online survey sampling (Bauermeister et al., 2012; Fricker, 2008), between July 2017 and January 2018. Participants were recruited from various online venues to participate in the “ProfileD Study.” The first and primary recruitment venue was Facebook™, one of the most popular and widely used social media websites on the internet. The second recruitment venue was Scruff™, a mobile app for gay and bisexual men to meet one another for sex or dating. The vast majority of participants were recruited through these two venues (Facebook = 89.6%; Scruff = 7.9%; Other = 2.5%). A small number of participants who had participated in a past study conducted by external research associates opted to participate in this study. Colleagues at Emory University Rollins School of Public Health PRISM Health research center, which run the American Men’s Internet Survey (AMIS; Zlotorzynska et al., 2019), had a small list of participants who wished to be contacted again for future studies. This Emory-based research center sent out email invites to eligible past participants of their AMIS study who requested to be contacted about future research opportunities and provided them with a link to the screening questionnaire for the ProfileD Study.

Prospective participants viewed advertisements for the study in each respective venue and clicked on a study link embedded in the advertisement that directed them to the study webpage. The advertisements on Facebook were only made viewable to men in the targeted age range who lived in the USA. Facebook ads were further tailored to target individuals who (1) indicated that they were “interested in” men, or who omitted information on the gender in which they were interested; (2) indicated interest in various LGBTQ-related pages on Facebook; (3) matched Facebook’s behavior algorithms for US African American Multicultural Affinity; or (4) indicated interest in various pages related to popular Black culture.

Screening and Consent

Once participants clicked on the link in the study advertisement, they were directed to the study webpage, which was a survey hosted on Qualtrics. Participants then completed a set of screening questions to determine their eligibility. Prospective participants responded to a series of yes or no questions about their gender, age, racial/ethnic identity, sexual orientation/sexual behavior, mobile app or website use, and residence. Prospective participants who met the eligibility criteria and completed the screening form were brought to a consent page, which contained detailed study information (i.e., purpose of the research, description of participant involvement, risk/discomforts; benefits; confidentiality etc.). Those consenting to participate proceeded to the full survey.

Procedure

Those consenting to participate in the study completed a survey on Qualtrics lasting 30 to 45 min. Participants were not compensated for taking the survey. While completing the survey, participants were permitted to save their answers and return to the survey at a later time if they were not able to complete it in a single sitting. Study data were kept in an encrypted and firewall-protected server, and the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan approved all study procedures.

Measures

Outcome Variables

The two dependent variables used in this study include Depressive Symptoms and Feelings of Self-Worth.

Depressive Symptoms

Data was collected on participants’ self-reported depressive symptoms in the past week to create a depressive symptoms score. The score was created using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, where the mean of 20 items was computed to generate an overall CES-D score, ranging from 1 to 4 (Radloff, 1977; Roberts, 1980). Participants were presented with a series of statements and were asked to indicate how often they have experienced each one. Participants responded to such statements as: “I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends” and “I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing.” Each item was measured using a 4-point Likert scale containing the following values: 1 = “rarely (less than 1 day),” 2 = “some (1–2 days),” 3 = “occasionally (3–4 days),” 4 = “most (5–7 days).” Four items on the scale were reverse-coded so that all responses were in directional alignment; higher scores indicate higher self-reported levels of depressive symptoms in the past week. The Cronbach’s alpha value for depressive symptoms demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.920).

Feelings of Self-Worth

Data was collected on participants’ self-reported feelings of self-worth to create a Self-Worth score. The score was created using the Feelings of Self-Worth Measure, where the mean of 14 items was computed to generate a self-worth mean index, ranging from 1 to 9 (Critcher & Dunning, 2015). Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they agree with a series of statements, such as, “Overall, I feel positively towards myself right now,” “I feel very much like a person of worth,” “I feel inferior at this moment.” Each item was measured using a 9-point Likert scale containing the following anchor values: 1 = “Not at all” and 9 = “Extremely.” Seven items on the scale were reverse-coded so that all responses were in directional alignment; higher scores indicate higher self-reported feelings of self-worth. The Cronbach’s alpha value for depressive symptoms demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.952).

Control Variables

The control variables in this study include self-perceived sexual attractiveness, perceived rejection, and four sociodemographic variables (age, relationship status, mobile app/website use for partner seeking, and educational attainment). Sexual orientation is reported for descriptive purposes only.

Self-Perceived Sexual Attractiveness

Data was collected on the degree to which participants feel that they are sexually attractive to create a self-perceived sexual attractiveness score. The score was created using the Self-Perceived Sexual Attractiveness Scale (SPSA), where the mean of 6 items was computed to generate an SPSA mean index, ranging from 1 to 7 (Amos & McCabe, 2015). Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed with a series of statements, such as, “I believe I can attract sexual partners,” “I feel I am sexy,” “I feel that others may perceive that a sexual relationship with me would be sexually fulfilling.” Each item was measured using a 7-point Likert scale containing the following anchor values: 1 = “Strongly disagree” and 7 = “Strongly agree.” Higher scores indicate higher self-reported levels of SPSA. The Cronbach’s alpha value for SPSA demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.952).

Perceived Rejection

Data was collected on the degree to which participants feel that they are rejected by others to create a perceived rejection score. The score was created using the Perceived Rejection Scale, where the mean of 4 items was computed to generate a mean perceived rejection index, ranging from 0 to 4 (Berenson et al., 2011). Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which a series of statements was true at the immediate moment. The statements were as follows: “I am accepted by others,” “I am abandoned,” “I am rejected by others,” “My needs are being met.” Each item was measured using a 5-point Likert scale containing the following values: 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “a little,” 2 = “moderately,” 3 = “quite a bit,” 4 = “extremely.” Two items on the scale were reverse-coded so that all responses were in directional alignment; higher scores indicate higher self-reported levels of perceived rejection. The Cronbach’s alpha value for perceived rejection demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = 0.768).

Internalized Racism

Data were collected on participants’ self-reported internalized racism to create an internalized racism score. The score was created using the Appropriated Racial Oppression Scale (AROS), where the mean of 24 items was computed to generate an AROS mean index, ranging from 1 to 7 (Campón & Carter, 2015). Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed with a series of statements, such as, “Sometimes I have a negative feeling about being a member of my race,” “I find persons with lighter skin-tones to be more attractive,” “People of my race shouldn’t be so sensitive about race/racial matters.” Each item was measured using a 7-point Likert scale containing the following anchor values: 1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree. Higher scores indicate higher self-reported levels of internalized racism. The Cronbach’s alpha value for internalized racism demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.911).

Sociodemographics

The age, relationship status, frequency of mobile app/website use for partner seeking, educational attainment, HIV status, and sexual orientation of each participant were based on self-report. Participants were instructed to provide their numerical age; no data on date of birth was collected. Participants were asked to indicate whether or not they were in a relationship by responding to the question, “are you single?” with a yes or no response. Participants were asked to indicate how often they use a mobile app or website in a typical month to seek partners for casual sex. Frequency of mobile app/website use to find partners was measured using a 6-point Likert scale containing the following values: 1 = “Once a month or less,” 2 = “2–3 times a month,” 3 = “About once a week,” 4 = “2–6 times a week,” 5 = “About once a day,” 6 = “More than once a day.” Higher scores indicated higher self-reported frequency of mobile app/website-based partner seeking for casual sex. Educational attainment was measured using a 5-point Likert scale containing the following values: 1 = “Less than high school,” 2 = “High school graduate,” 3 = “Some college,” 4 = “College graduate,” 5 = “Post College.” Higher scores indicated higher self-reported levels of educational attainment. Participants were asked to indicate their HIV status by responding to the questions, “have you ever tested positive for HIV?” with a yes or no response. Finally, participants were asked to indicate their sexual orientation. Participants were permitted to select one of 11 sexual orientation categories: 1 = “Gay,” 2 = “Bisexual,” 3 = “Same Gender Loving,” 4 = “Queer,” 5 = “Straight,” 6 = “Trade,” 7 = “DL (Down Low),” 8 = “Homothug,” 9 = “Questioning,” 10 = “Other,” 11 = “Unsure.”

Independent Variables

Data were collected on participants’ self-reported experiences of racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) using a researcher-developed RSD scale (Wade & Harper, 2021). The RSD scale consists of 60 individual items that capture 30 unique experiences. Each unique experience has two corresponding items: one that captures the effect (i.e., to what degree the experience has a negative effect on the participant) and the frequency (i.e., how often a participant encounters the experience). Experiences may also occur in one of two contexts: partner browsing (i.e., viewing user profiles on mobile apps/websites) and partner negotiation (i.e., written communication between users on mobile apps/websites). All items within the partner browsing context were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, for both the effect (0 = Strongly disagree, 1 = “Disagree,” 2 = “Neutral,” 3 = “Agree,” 4 = Strongly agree) and the frequency (0 = “Never,” 1 = “Some of the time,” 2 = “Half of the time,” 3 = “Most of the time,” 4 = “All of the time”) items. All items within the partner negotiation context were measured on a 6-point Likert scale, for both the effect (0 = “I have not contacted this group,” 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree) and the frequency (0 = “I have not contacted this group,” 1 = Never, 2 = Some of the time, 3 = Half of the time, 4 = Most of the time, 5 = All of the time) items.

The effect and frequency scores for all items within the partner browsing context were multiplied to develop an impact score, ranging from 0 to 16. This impact score was divided by 16 and multiplied by 100 to result in a final impact score for all partner browsing items (N = 20), ranging from 0 to 100. Likewise, the effect and frequency scores for all items within the partner negotiation context were multiplied to develop an impact score, ranging from 0 to 25. For ease of interpretation, this impact score was divided by 25 and multiplied by 100 to result in a final impact score for partner negotiation items (N = 10), ranging from 0 to 100. Subsequently, all partner browsing and partner negotiation impact scores ranged from 0 to 100, resulting in 30 multiplicative terms that represented the complete RSD scale.

White Superiority

The mean of 8 impact items was computed to generate a White superiority score, ranging from 0 to 100. Participants responded to such items as, “How often do you see profiles from White people clearly state that they want to meet other White people?” and “When I see a profile from White people clearly state that they do NOT want to meet people of my race/ethnicity I have a negative reaction.” The Cronbach’s alpha value for White superiority demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.832).

White Rejection

The mean of 2 impact items was computed to generate a White rejection score, ranging from 0 to 100. Participants responded to such items as, “How often are your messages rejected by White people?” and “When my messages are ignored by White people I have a negative reaction.” The Cronbach’s alpha value for White rejection demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.898).

Same-Race Rejection

The mean of 2 impact items was computed to generate a same-race rejection score, ranging from 0 to 100. Participants responded to such items as, “How often are your messages ignored by people of your own race/ethnicity?” and “When my messages are rejected by people of my own race/ethnicity I have a negative reaction.” The Cronbach’s alpha value for same-race rejection demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.865).

White Physical Objectification

The mean of 2 impact items was computed to generate a white physical objectification score, ranging from 0 to 100. Participants responded to such items as, “When White people express a desire for a specific physical trait related to my race/ethnicity, I have a negative reaction” and “How often do White people express a desire for a specific physical trait related to your race/ethnicity?” The Cronbach’s alpha value for White physical objectification demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.830).

Same-Race Physical Objectification

The mean of 2 impact items was computed to generate a same-race physical objectification score, ranging from 0 to 100. Participants responded to such items as, “How often do you see profiles from people of your race/ethnicity expressing a desire for a specific physical trait related to other people of your race/ethnicity?” and “When people of my race/ethnicity express a desire for a specific physical trait related to my race/ethnicity I have a negative reaction.” The Cronbach’s alpha value for same-race physical objectification demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = 0.731).

Data Collection and Cleaning

Best practices for online data collection were employed, which involve the identification of valid/invalid, fraudulent, and suspicious data (Bauermeister et al., 2012). Such practices include detecting suspicious response patterns to survey items (e.g., selecting the same response for every question throughout the survey) and/or completing the survey in an unrealistically short amount of time. Best practices also include determining whether multiple surveys were submitted from the same IP address. However, because surveys are administered anonymously, no IP address information was collected from study participants. Given that no incentive was offered as a part of this study, we have little reason to suspect that an individual would complete the survey multiple times.

Data Analytic Strategy

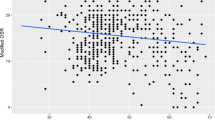

Descriptive statistics were computed for the study sample, including mean scores, frequency counts, and percentages for demographic characteristics and study variables. The rejection, objectification, and White superiority subscales were examined in multivariable linear regression models using depressive symptoms and feelings of self-worth as the dependent variable. These three categories of RSD were examined in three separate models due to their being conceptually distinct from one another, as demonstrated in the literature and our prior scale development work on RSD (Wade & Harper, 2021). In total, six regression models were estimated (three for depression and three for self-worth). Each model also included theoretically informed control variables (age, education, HIV-status, frequency of mobile app/website use for partner seeking, relationship status, perceived rejection, internalized racism, and self-perceived sexual attractiveness). Due to the use of a newly developed RSD scale, we sought to establish more stringent cut-off values to reduce the risk of encountering a type I error. Thus, a significance value of p < 0.01 was selected as the minimum value to establish statistical significance.

Results

Sample Description

Data were collected on a total of 603 participants. The median survey completion time was 34 min. The mean age of the sample was 24.46 years (SD = 3.17), and most study participants (87%) were single. The majority of participants identified as gay (71.1%) or bisexual (16.2%), and a sizable number of participants (14.9%) reported being HIV-positive. The sample was fairly well-educated, as nearly half (46.6%) of participants had completed a college degree and/or received a post-graduate education. The other half had mostly received some college education (41.8%), and only two participants (0.3%) had not completed high school. Participants varied on their app use, with approximately a quarter of participants (25.7%) reporting a minimum of once-a-day usage, and nearly half of participants (46.7%) reporting less than once-a-week usage. Participants reported moderate levels of self-worth (M = 6.07) and depressive symptoms (M = 1.85). Participants also reported moderate perceived rejection (M = 1.92), moderate to high self-perceived sexual attractiveness (M = 5.07), and low to moderate internalized racism (M = 2.83) (see Table 1).

Multivariable Analyses

White Superiority

In the model examining the relationship between depressive symptoms and White superiority (F(9, 602) = 27.51, p < 0.001; R2 = 29.1%), depressive symptoms had a significant association with White superiority, where higher scores on White superiority were associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms (β = 0.11, p < 0.01). Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with perceived sexual attractiveness (β = −0.18, p < 0.001), where higher scores on perceived sexual attractiveness were associated with lower rates of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were also significantly associated with internalized racism (β = 0.16, p < 0.001) and perceived rejection (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), where higher scores on these variables were associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms.

In the model examining the relationship between feelings of self-worth and White superiority (F(9, 602) = 34.70, p < 0.001; R2 = 34.2%), feelings of self-worth had no significant association with White superiority. Feelings of self-worth were significantly associated with perceived sexual attractiveness (β = 0.39, p < 0.001), where higher scores on perceived sexual attractiveness were associated with higher feelings of self-worth. Feelings of self-worth were also significantly associated with perceived rejection (β = −0.22, p < 0.001), where higher scores on perceived rejection were associated with lower feelings of self-worth (see Table 2).

Rejection

In the model examining the relationship between depressive symptoms and rejection (F(9, 602) = 25.98, p < 0.001; R2 = 30.2%), depressive symptoms had no significant association with White rejection. Depressive symptoms were, however, significantly associated with same-race rejection, where higher scores on same-race rejection (β = −0.16, p < 0.001) were associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with age (β = −0.11, p < 0.01) and perceived sexual attractiveness (β = −0.19, p < 0.001), where higher scores on these variables were associated with lower rates of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were also significantly associated with internalized racism (β = 0.16, p < 0.001) and perceived rejection (β = 0.29, p < 0.001), where higher scores on these variables were associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms.

In the model examining the relationship between feelings of self-worth and rejection (F(10, 601) = 30.99, p < 0.001; R2 = 34%), feelings of self-worth had no significant association with White rejection nor same-race rejection. Feelings of self-worth were significantly associated with perceived attractiveness (β = 0.40, p < 0.001), where higher scores on perceived sexual attractiveness were associated with higher feelings of self-worth. Feelings of self-worth was also significantly associated with perceived rejection (β = −0.23, p < 0.001), where higher scores on perceived rejection were associated with lower feelings of self-worth (see Table 3).

Objectification

In the model examining the relationship between depressive symptoms and physical objectification (F(10, 601) = 26.06, p < 0.001; R2 = 30.2%), depressive symptoms had no significant association with same-race physical objectification. Depressive symptoms were, however, significantly associated with White physical objectification, where higher scores on White physical objectification were associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms (β = 0.14, p < 0.001). Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with age (β = −0.10, p < 0.01) and perceived sexual attractiveness (β = −0.20, p < 0.001), where higher scores on these variables were associated with lower rates of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were also significantly associated with internalized racism (β = 0.18, p < 0.001) and perceived rejection (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), where higher scores on these variables were associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms.

In the model examining the relationship between feelings of self-worth and physical objectification (F(10, 601) = 32.48, p < 0.001; R2 = 35.1%), feelings of self-worth had no significant association with same-race physical objectification. Feelings of self-worth were, however, significantly associated with White physical objectification, where higher scores on White physical objectification (β = −0.11, p < 0.01) were associated with lower feelings of self-worth. Feelings of self-worth were significantly associated with perceived sexual attractiveness (β = 0.40, p < 0.001), where higher scores on perceived attractiveness were associated with higher feelings of self-worth. Feelings of self-worth were also significantly associated with perceived rejection (β = −0.21, p < 0.001) and internalized racism (β = −0.10, p < 0.01), where higher scores these variables were associated with lower feelings of self-worth (see Table 4).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the relationship between racialized sexual discrimination and markers of psychological wellbeing, among a sample of YSMBM who use the internet to meet partners for sexual encounters. Researchers have suggested that RSD may have an adverse effect on psychological wellbeing among gay and bisexual men of color, but there is minimal research examining this association using quantitative methods (Paul et al., 2010). This study aimed to contribute to the evidence base surrounding RSD and its relationship to psychological wellbeing among YSMBM. We used a novel, preliminarily validated scale of RSD for this investigation (Wade & Harper, 2021). We examined the association between five RSD subscales (White superiority, White rejection, same-race rejection, White physical objectification, same-race physical objectification) on two psychological health outcomes (depressive symptoms and feelings of self-worth), by estimating six multivariable regression models. We found that the White superiority, same-race rejection, and White physical objectification subscales were all significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms—and that the White physical objectification subscale was significantly associated with lower feelings of self-worth. The results of this study provide supporting evidence that RSD is associated with negative psychological health outcomes, particularly as it pertains to depressive symptoms.

RSD Subscales and Psychological Wellbeing

The White superiority, same-race rejection, and White physical objectification subscales were all significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms among YSMBM. In all cases, higher scores on these variables were associated with higher self-reported depressive symptoms. Overall, these findings support researchers’ speculations that RSD may have an adverse effect on psychological wellbeing of YSMBM (Paul et al., 2010). Contrary to our hypothesis, the White rejection subscale failed to achieve statistical significance in both the depressive and self-esteem models. This is noteworthy in light of the significant results found for both the White superiority subscale, and the same-race rejection subscale.

First, this finding suggests that YSMBM may be especially harmed by the experience of being discriminated against by members of their own racial ethnic group, more so that being discriminated against by other White people. The experiences of being rejected by one’s own racial/ethnic group have received minimal attention in the literature, but this topic did arise in focus groups that preceded the current study (Wade & Harper, 2020b). Participants in the focus groups expressed strong negative emotions about the experience of being rejected by members of their own racial/ethnic group, or by other POC. These reports complement the findings noted in this study. Researchers may thus want to pay particular attention to the experiences of YSMBM being discriminated against by other YSMBM in future research on RSD.

Second, this finding may suggest that YSMBM have developed a strong enough coping capacity to deal with rejection from White men at a one-on-one interpersonal level, but still experience psychological harm from witnessing the elevation of Whiteness as superior in the broader social landscape of online dating. Parallels may be drawn between the sociocultural embeddedness of racism in broader society, juxtaposed with the interpersonal discrimination that men of color may experience on a day to day basis. Researchers have noted that the former may have an overall greater impact on the health and wellbeing of racial/ethnic minorities, and also creates a social context that gives rise to individual-level discrimination (Bailey et al., 2017; Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Gee & Ford, 2011; Winder & Lea, 2019). In the case of RSD, YSMBM may be able to develop strategies to mitigate the microaggressions that they encounter directly, but they are generally powerless to alter a social environment that holds Whiteness in greater esteem and considers people of color to be of lesser value. Researchers may want to devote attention to role of White superiority in dating mobile apps/websites frequented by gay men and continue to examine its association with psychological wellbeing among YSMBM.

The White physical objectification subscale describes the objectification of YSMBM on the basis of their physical traits and was associated with higher self-reported depressive symptoms among the study sample. This finding suggests that objectification may be psychologically harmful for Black YSMBM. Objectification is one of the more unique RSD experiences, being the only type of experience that may provide men with sexual opportunities, whereas all other manifestations of RSD typically deny men sexual opportunities. Although successful sexual encounters may ultimately be the goal for men who seek partners online, this finding suggests that certain sexual encounters—those that are driven by the promotion of racial/ethnic stereotypes, or the eroticization or racial/ethnic features—may come at a cost to the psychological health of YSMBM. McKeown et al. (2010) spoke to this complex phenomenon, noting that YSMBM in their studies felt as though they had little value beyond servicing a racialized sexual need when negotiating or having a sexual encounter with White men. The White physical objectification subscale was also the only RSD subscale to achieve statistical significance in the self-worth models, where higher scores on this variable was associated with lower feelings of self-worth. As such, the phenomenon of White men objectifying Black men for their physical characteristics was the only manifestation of RSD to be significantly, and negatively, associated with both markers of psychological wellbeing. Therefore, this study provides preliminary evidence that this particular manifestation of RSD may be among the most impactful for YSMBM. Researchers may thus want to consider this potentially key variable in future research exploring the phenomenon of RSD.

Control Variables and Psychological Wellbeing

In the rejection and objectification depression models, being older was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms. This finding may reflect epidemiological trends in depression rates by age, where individuals between the age of 18 to 25 have higher rates of depressive symptoms than those between 25 and 49 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2020). In the context of RSD, it is also possible that men develop better coping capacities to deal with rejection and objectification after repeated exposure over time. However, we are not able to draw definitive conclusions about any temporal factors that affect the association between RSD and psychological wellbeing.

As suspected, perceived rejection and self-perceived sexual attractiveness were highly significant across all six models, where higher scores on perceived rejection were associated with worse psychological wellbeing, and higher scores on self-perceived sexual attractiveness were associated with better psychological wellbeing. These results are consistent with the literature examining the association between self-perceived sexual attractiveness and self-perceived rejection on psychological health outcomes (Amos & McCabe, 2017; Bale & Archer, 2013; Downey & Feldman, 1996; Nolan et al., 2003). Moreover, these two variables had the largest effect sizes of any variable across all six models, suggesting that they are two essential factors to account for in the context of RSD. Participants reported moderate to high scores on SPSA overall, which may be reflective of resilient characteristics among the study sample. Given that scoring higher on SPSA was associated with higher psychological wellbeing, future research may examine whether perceived attractiveness or positive body image perceptions may be protective in the context of online dating and RSD.

Finally, higher scores on internalized racism were significantly associated with greater depressive symptoms and had a reasonably high effect size relative to other variables in the model. These findings complement research identifying a positive association between internalized racism and depressive outcomes (Molina & James, 2016; Mouzon & McLean, 2017), and add to a relatively small literature examining the association between internalized racism and psychological wellbeing. Given such findings, it will be important for researchers to continue examining the role of internalized racism in the context of RSD.

Strengths and Limitations

Given that this study used cross-sectional data, it is not possible to draw conclusions about causal relationships between the variables observed. This study is also limited by the use of a new measure that has not been subject to extensive psychometric testing with replicable results. Moreover, this new scale has not been subject to confirmatory factor analyses, and thus, further refinement and construct validity assessments of the scale is needed. In addition, the RSD scale only accounts for racialized experiences that are encountered online. The scale does not account for RSD experiences during an in-person sexual encounter, though it is possible that racialized discriminatory treatment that is experienced in-person may also contribute significantly to poor psychological health outcomes.

This study also focuses exclusively on the experiences of Black men, and the scale only accounts for racialized dynamics that exists between White men and a single racial/ethnic minority group (i.e., the race/ethnicity of the respondent—in this case, Black-identified men), or between members of the same racial/ethnic group. As such, the results of this study cannot be generalized to racial/ethnic minorities other than Black men, nor does it account for the discriminatory experiences that Black men may experience from other racial/ethnic minority groups. Moreover, this study does not account for variations in the demographics and/or sociocultural norms between different websites/mobile apps that YSMBM use (i.e., some venues may be predominantly White, while others may be more affirming/inclusive for people of color). Moving forward, it will be important to investigate the ways in which RSD may manifest differentially based on venue, to better capture some of the cultural nuances of virtual spaces.

The exclusion of trans-identified men is another limitation of this study, though we concluded that it would be best to limit the current study to cisgender men for several reasons. First, we sought to limit the heterogeneity of the sample, as obtaining a more homogenous sample would also allow us to speak more accurately to the experiences of the specific population of focus, and to the phenomenon itself. Second, the limited time-frame of the project did not enable us to gather enough data on trans-identified individuals to make meaningful inferences about this population. In order to speak to a broader population of YSMBM, future research on this phenomenon should aim to be inclusive of trans-identified individuals.

This study, however, does present a number of strengths. First, the study benefits from a relatively large sample size of YSMBM, enhancing its generalizability to this population. Second, the RSD scale is an innovative approach to investigating discrimination experienced by YSMBM. It provides a largely under-examined perspective on instances of racialized experiences that are commonly reported among this population in online partner-seeking venues. Third, the use of this measure provides an opportunity to determine the extent to which such experiences contribute negatively to psychological wellbeing. Given the pervasiveness of online partner-seeking among YSMBM, using the RSD scale in studies on discrimination and health may yield results that are significant in scope. Moreover, it provides an opportunity to contribute to a limited knowledge base on important health outcomes among YSMBM that have received less attention in the health literature.

Implications

This work has implications for policy and practice across multiple levels. First, our findings may be relevant for clinicians and other practitioners who work with YSMBM. Professionals may benefit from continuing education, workshops, and other training modules that incorporate RSD into the curriculum, so that they may be better equipped to attend to those who may be regularly experiencing RSD. Such modules are especially pertinent for practitioners who address the complex social, sexual, and romantic lives of YSMBM at a developmental stage when forming intimate connections is at their most salient and in an era where virtual networking is at an all-time high. Practitioners’ familiarity with RSD will become even more important as the literature on this phenomenon becomes more robust, and as research in this area begins to focus on individual-level interventions.

At the community level, researchers may also consider developing robust awareness initiatives within LGBT communities to convey the scope and impact of RSD on racial/ethnic minorities. Such initiatives may help mobilize the community to develop health promotion campaigns to discourage RSD. Allies and members of the LGBT community have already pursued initiatives around the subject of LGBT suicide and bullying, such as the Trevor Project and the “It Gets Better” campaign, to widespread recognition and varying degrees of success (Hendricks et al., 2012; Lister et al., 2013; Muller, 2012; Wiederhold, 2014). Awareness around RSD has already begun to follow suit, with blogs and smaller media outlets reporting on the subject, but has yet to breach the threshold of broader community and/or national recognition. The success of these previous campaigns suggests that concerted efforts to raise awareness around RSD could have a far-reaching and meaningful impact.

Finally, researchers may consider engaging the administrators of mobile apps and websites that cater to sexual minority men. Site administrators have broad authority and oversight to institute anti-racism policies on their platforms and could potentially hold users accountable for what they write on their profiles. Many of these apps and websites already have pop-up and banner ads for a wide assortment of products, campaigns, and events—including those that promote community health. This represents yet another opportunity to address RSD and highlight its potentially harmful effects, as well as discourage users from behaving in a discriminatory manner toward other users of color.

Conclusion and Directions for Future Research

Racialized sexual discrimination appears to have a significant association with psychological health outcomes among YSMBM. However, because this is the first study to examine psychological health using a newly developed scale of RSD, additional studies with replicated results are needed to advance the scientific understanding of this phenomenon. Moving forward, it will be important for the current iteration of the RSD scale to continue to be revised and tested using confirmatory analyses. This will enhance the validity of the scale, which will make it more useful in future studies examining its association with health among sexual minority men of color.

Future studies should also examine the RSD experiences of racial/ethnic groups other than YSMBM. Researchers have reported that nearly all racial/ethnic minority groups may be the target of RSD, but RSD may manifest differently for different racial/ethnic groups. For example, the ways in which sexual minority men of color are eroticized differ based on the sexual scripts and stereotypes that are ascribed to a particular racial/ethnic group (McKeown, et al., 2010; Paul et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2009). Some racial/ethnic groups may also experience RSD more frequently than others, and there may be some groups for whom RSD may have a stronger effect. It will therefore be useful for researchers to perform comparative analyses across different racial/ethnic groups to determine which groups may be at less, or greater, risk for adverse psychological health outcomes. Finally, it will be important to account for complex developmental and lifespan factors as it relates to sexual minority men’s experiences of, and responses to, RSD—as well as the ways in which men engage with and navigate virtual venues to meet intimate partners. Overall, RSD remains a potentially important yet critically understudied phenomenon, and there is ample room for researchers to continue exploring its association with health outcomes among young sexual minority men of color.

References

Amos, N., & McCabe, M. P. (2015). Conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of sexual attractiveness: Are there differences across gender and sexual orientation? Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.057

Amos, N., & McCabe, M. (2017). The importance of feeling sexually attractive: Can it predict an individual’s experience of their sexuality and sexual relationships across gender and sexual orientation? International Journal of Psychology, 52(5), 354–363.

Arnold, E. A., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2014). ‘Triply cursed’: Racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(6), 710–722.

Badal, H. J., Stryker, J. E., DeLuca, N., & Purcell, D. W. (2018). Swipe right: Dating website and app use among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 22(4), 1265–1272.

Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463.

Bale, C., & Archer, J. (2013). Self-perceived attractiveness, romantic desirability and self-esteem: A mating sociometer perspective. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(1), 147470491301100100.

Balsam, K. F., Molina, Y., Beadnell, B., Simoni, J., & Walters, K. (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023244

Bauermeister, J. A., Carballo-Diéguez, A., Ventuneac, A., & Dolezal, C. (2009). Assessing motivations to engage in intentional condomless anal intercourse in HIV risk contexts (“bareback sex”) among men who have sex with men. AIDS Education & Prevention, 21(2), 156–168.

Bauermeister, J. A., Pingel, E., Zimmerman, M., Couper, M., Carballo-Diéguez, A., & Strecher, V. J. (2012). Data quality in web-based HIV/AIDS research: Handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods, 24(3), 272–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X12443097

Bhambhani, Y., Flynn, M. K., Kellum, K. K., & Wilson, K. G. (2020). The role of psychological flexibility as a mediator between experienced sexual racism and psychological distress among men of color who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1269-5

Berenson, K. R., Downey, G., Rafaeli, E., Coifman, K. G., & Paquin, N. L. (2011). The rejection–rage contingency in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(3), 681–690.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62(3), 465–480.

Bowleg, L. (2013). “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 754–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0152-4

Brennan, D. J., Asakura, K., George, C., Newman, P. A., Giwa, S., Hart, T. A., ... & Betancourt, G. (2013). “Never reflected anywhere”: Body image among ethnoracialized gay and bisexual men. Body Image, 10(3), 389–398.

Callander, D., Holt, M., & Newman, C. E. (2012). Just a preference: Racialised language in the sex-seeking profiles of gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(9), 1049–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.714799

Callander, D., Newman, C. E., & Holt, M. (2015). Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes towards sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 13(4), 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6

Campón, R. R., & Carter, R. T. (2015). The Appropriated Racial Oppression Scale: Development and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000037

Cokley, K. O. (2002). Testing Cross’s revised racial identity model: An examination of the relationship between racial identity and internalized racialism. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(4), 476–483.

Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Critcher, C. R., & Dunning, D. (2015). Self-affirmations provide a broader perspective on self-threat. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214554956

Cyrus, K. (2017). Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(3), 194–202.

Diaz, R. M., Ayala, G., Bein, E., Henne, J., & Marin, B. V. (2001). The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 927–932.

Dahlenburg, S. C., Gleaves, D. H., Hutchinson, A. D., & Coro, D. G. (2020). Body image disturbance and sexual orientation: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image, 35, 126–141.

Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1327–1343.

Ehlinger, P. P., & Blashill, A. J. (2016). Self-perceived vs. actual physical attractiveness: Associations with depression as a function of sexual orientation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 189(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.071

Fricker, R. D. (2008). Sampling methods for web and e-mail surveys. In N. Fielding, R. M. Lee, & G. Blank (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of online research methods (pp. 195–216). Sage.

Frost, D. M., Stirratt, M. J., & Ouellette, S. C. (2008). Understanding why gay men seek HIV-seroconcordant partners: Intimacy and risk reduction motivations. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 10(5), 513–527.

Gee, G. C., & Ford, C. L. (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 115–132.

Golub, S. A., Starks, T. J., Payton, G., & Parsons, J. T. (2012). The critical role of intimacy in the sexual risk behaviors of gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 16(3), 626–632.

Goodwill, J. R., Taylor, R. J., & Watkins, D. C. (2019). Everyday discrimination, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation among African American men. Archives of Suicide Research, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1660287

Graham, L. F., Aronson, R. E., Nichols, T., Stephens, C. F., & Rhodes, S. D. (2011). Factors influencing depression and anxiety among black sexual minority men. Depression Research and Treatment, 587984. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/587984 (E-pub)

Grov, C., Breslow, A. S., Newcomb, M. E., Rosenberger, J. G., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2014). Gay and bisexual men’s use of the Internet: Research from the 1990s through 2013. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(4), 390–409.

Harper, G. W., & Wilson, B. D. M. (2016). Situating sexual orientation and gender identity diversity in context and communities. In M. A. Bond, C. B. Keys, & I. Serrano-Garcia (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Hendricks, L., Lumadue, R., & Waller, L. R. (2012). The evolution of bullying to cyber bullying: An overview of the best methods for implementing a cyber bullying preventive program. National Forum Journal of Counseling and Addiction, 1(1), 1–9.

Hidalgo, M. A., Layland, E., Kubicek, K., & Kipke, M. (2020). Sexual racism, psychological symptoms, and mindfulness among ethnically/racially diverse young men who have sex with men: A moderation analysis. Mindfulness, 11(2), 452–461.

Hightow-Weidman, L. B., Hurt, C. B., Phillips 2nd, G., Jones, K., Magnus, M., Giordano, T. P., … & The YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group. (2011). Transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance among young men of color who have sex with men: A multicenter cohort analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(1), 94–99.

Huebner, D. M., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2004). Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health, 94(7), 1200–1203.

Hughes, M., Kiecolt, K. J., Keith, V. M., & Demo, D. H. (2015). Racial identity and well-being among African Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly, 78(1), 25–48.

Jamil, O. B., Harper, G. W., & Fernandez, M. I. (2009). Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay-bisexual-questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(3), 203–214.

Jha, M. (2015). The global beauty industry: Colorism, racism, and the national body. Routledge.

Lipsky, S. (1987). Internalized racism. Rational Island Publishers.

Lister, C. E., Brutsch, E., Johnson, A., Boyer, C., Hall, P. C., & West, J. H. (2013). It gets better: A content analysis of health behavior theory in anti-bullying YouTube videos. International Journal of Health, 1(2), 17–24.

Loiacano, D. K. (1989). Gay identity issues among Black Americans: Racism, homophobia, and the need for validation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 68(1), 21–25.

Magnus, M., Jones, K., Philips, 2nd G., Binson, D., Hightow-Weidman, L. B., Richards-Clarke, C., … & The YMSM of Color Special Projects of National Significance Initiative Study Group. (2010). Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: Results from the outreach, care, and prevention to engage HIV-seropositive young MSM of color special project of national significance initiative. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 53(4), 529–536.

McKeown, E., Nelson, S., Anderson, J., Low, N., & Elford, J. (2010). Disclosure, discrimination and desire: Experiences of Black and South Asian gay men in Britain. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(7), 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2010.499963

Meanley, S., Bruce, O., Hidalgo, M. A., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2020). When young adult men who have sex with men seek partners online: Online discrimination and implications for mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(4), 418–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000388

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Mogilski, J. K., Memering, S. L., Welling, L. L., & Shackelford, T. K. (2015). Monogamy versus consensual non-monogamy: Alternative approaches to pursuing a strategically pluralistic mating strategy. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0658-2

Molina, K. M., & James, D. (2016). Discrimination, internalized racism, and depression: A comparative study of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(4), 439–461.

Mouzon, D. M., & McLean, J. S. (2017). Internalized racism and mental health among African-Americans, US-born Caribbean Blacks, and foreign-born Caribbean Blacks. Ethnicity & Health, 22(1), 36–48.

Muller, A. (2012). Virtual communities and translation into physical reality in the ‘It Gets Better Project.’ Journal of Media Practice, 12(3), 269–277.

Nolan, S. A., Flynn, C., & Garber, J. (2003). Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 745–755.

O’Donnell, S., Meyer, I. H., & Schwartz, S. (2011). Increased risk of suicide attempts among Black and Latino lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Public Health, 101(6), 1055–1059. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300032

Parsons, J. T., Starks, T. J., DuBois, S., Grov, C., & Golub, S. A. (2013). Alternatives to monogamy among gay male couples in a community survey: Implications for mental health and sexual risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(2), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9885-3

Paul, J. P., Ayala, G., & Choi, K. (2010). Internet sex ads for MSM and partner selection criteria: The potency of race/ethnicity online. Journal of Sex Research, 47(6), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903244575

Paz-Bailey, G., Hoots, B. E., Xia, M., Finlayson, T., Prejean, J., Purcell, D. W., NHBS Study Group. (2017). Trends in internet use among men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 75(Suppl 3), S288–S295.

Pew Research Center. (2020, February 6). The virtues and downsides of online dating [Report]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/06/the-virtues-and-downsides-of-online-dating/

Plummer, M. D. (2007). Sexual racism in gay communities: Negotiating the ethnosexual marketplace (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from University of Washington ResearchWorks Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/1773/9181

Pyke, K. D. (2010). What is internalized racial oppression and why don’t we study it? Acknowledging Racism’s Hidden Injuries. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 551–572.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Reece, R. L. (2016). What are you mixed with: The effect of multiracial identification on perceived attractiveness. The Review of Black Political Economy, 43(2), 139–147.

Roberts, R. E. (1980). Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research, 126(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4

Robinson, B. A. (2015). “Personal preference” as the new racism: Gay desire and racial cleansing in cyberspace. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(2), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214546870

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921–928.

Schmitz, R. M., Robinson, B. A., Tabler, J., Welch, B., & Rafaqut, S. (2020). LGBTQ+ Latino/a young people’s interpretations of stigma and mental health: An intersectional minority stress perspective. Society and Mental Health, 10(2), 163–179.

Sherman, D. K., & Cohen, G. L. (2006). The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 183–242.

Slavin, S. (2009). ‘Instinctively, I’m not just a sexual beast’: The complexity of intimacy among Australian gay men. Sexualities, 12(1), 79–96.

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 261–302.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20–07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Szymanski, D. M., & Gupta, A. (2009). Examining the relationship between multiple internalized oppressions and African American lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning persons’ self-esteem and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 110–118.

Tappan, M. B. (2006). Reframing internalized oppression and internalized domination: From the psychological to the sociocultural. Teachers College Record, 108(10), 2115–2144.

Thai, M. (2020). Sexual racism is associated with lower self-esteem and life satisfaction in men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(1), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1456-z

Verkuyten, M. (1998). Perceived discrimination and self-esteem among ethnic minority adolescents. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(4), 479–493.

Wade, R. M., & Harper, G. W. (2017). Young black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men: A review and content analysis of health-focused research between 1988 and 2013. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1388–1405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315606962

Wade, R. M., & Harper, G. W. (2020a). Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) in the age of online sexual networking: Are gay/bisexual men of color at elevated risk for adverse psychological health? American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3–4), 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12401

Wade, R. M., & Harper, G. W. (2020b). Toward a multidimensional construct of racialized sexual discrimination (RSD): Implications for scale development. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000443

Wade, R. M., & Harper, G. W. (2021). Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) in online sexual networking: Moving from discourse to measurement. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(6), 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1808945

Wade, T. J. (2000). Evolutionary theory and self-perception: Sex differences in body esteem predictors of self-perceived physical and sexual attractiveness and self-esteem. International Journal of Psychology, 35(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075900399501

White, J. M., Reisner, S. L., Dunham, E., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2014). Race-based sexual preferences in a sample of online profiles of urban men seeking sex with men. Journal of Urban Health, 91(4), 768–775.

Wiederhold, B. K. (2014). Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A deadly combination. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Network, 17(9), 569–570.

Wilson, B. D. M., & Harper, G. (2013). Race and ethnicity in lesbian, gay and bisexual communities. In C. J. Patterson & A. R. D’Augelli (Eds.), Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation (pp. 281–296). Oxford University Press.

Wilson, P. A., Val Wilson, P. A., Valera, P., Ventuneac, A., Balan, I., Rowe, M., & Carballo-Diéguez, A. (2009). Race-based sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering among men who use the internet to identify other men for bareback sex. The Journal of Sex Research, 46(5), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902846479

Winder, T. J., & Lea, C. H. (2019). “Blocking” and “Filtering”: A commentary on mobile technology, racism, and the sexual networks of young black MSM (YBMSM). Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6(2), 231–236.

Wohl, A. R., Garland, W. H., Wu, J., Chi-Wai, A., Boger, A., Dierst-Davies, R., ... & Jordan, W. (2011). A youth-focused case management intervention to engage and retain young gay men of color in HIV care. AIDS Care, 28(5), 988–997.

Wong, C. F., Schrager, S. M., Holloway, I. W., Meyer, I. H., & Kipke, M. D. (2014). Minority stress experiences and psychological well-being: The impact of support from and connection to social networks within the Los Angeles house and ball communities. Prevention Science, 15(1), 44–55.

Zlotorzynska, M., Sullivan, P., & Sanchez, T. (2019). The annual American men’s internet survey of behaviors of men who have sex with men in the United States: 2016 key indicators report. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(1), e11313.

Funding

This work was supported by a small dissertation grant awarded by the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies at the University of Michigan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.