Abstract

Access to early child education services has been proven to be an efficient tool in fighting educational inequalities. However, while wealthier families are likely to use childcare services, disadvantaged children tend to be left out. Research has explained this effect, known as Mathew Effect, and has studied both the constraints in the availability and affordability of childcare services, and the cultural norms surrounding motherhood. This paper aims to highlight other factors that also explain the Mathew Effect from a public policy perspective, beyond the economic barriers that limit access to formal childcare services. Through 34 interviews with mothers who have children between one and three years of age who attend both state and private nurseries in the city of Barcelona, we examine the characteristics of regulated childcare services and the objective factors of those mothers’ everyday lives in order to understand the decision-making processes involved in choosing childcare for the under-threes. The results indicate that sliding-scale pricing has allowed mothers with low incomes to access state nursery schools, while the quality of the services offered has served to attract the middle and upper classes. However, early childhood care services have not been adapted to the needs of working-class mothers who, although not being in a situation of social vulnerability, cannot afford private nurseries because of their high costs.

Résumé

L'accès aux services d'éducation de la petite enfance s'est avéré être un outil efficace pour lutter contre les inégalités scolaires. Cependant, alors que les familles plus riches utilisent les services de garde d'enfants, les enfants des familles plus pauvres auront tendance à être laissés pour compte. La recherche a expliqué cet effet, connu sous le nom d'effet Matthieu, et a étudié les obstacles créés à la fois par la disponibilité et l'abordabilité des services de garde d'enfants et aussi par les normes culturelles entourant la maternité. Ce travail vise à mettre en évidence d'autres facteurs explicatifs de l'effet Matthieu du point de vue des politiques publiques, au-delà des barrières économiques qui limitent l'accès aux services formels de garde d'enfants. À travers 34 entretiens avec des mères qui ont des enfants âgés entre un et trois ans et qui fréquentent des crèches publiques et privées de la ville de Barcelone, nous examinons les caractéristiques des services de garde d'enfants réglementés et les facteurs objectifs quotidiens. de ces mères à comprendre les processus décisionnels qui concourent au choix du mode de garde des enfants de moins de trois ans. Les résultats indiquent que la tarification sociale a permis aux mères à faible revenu d'accéder aux écoles maternelles publiques, tandis que la qualité des services offerts a servi à attirer les classes moyennes et supérieures. Cependant, les services d'accueil de la petite enfance ne sont pas adaptés aux besoins des mères de la classe ouvrière qui, sans être en situation de vulnérabilité sociale, ne peuvent s'offrir des garderies privées en raison de leurs coûts élevés.

Resumen

El acceso a los servicios de educación infantil ha demostrado ser una herramienta eficaz para combatir las desigualdades educativas. Sin embargo, mientras las familias más ricas utilizan los servicios de guardería, los niños de familias más desfavorecidas tienden a quedar al margen. La investigación ha explicado este efecto, conocido como Efecto Mateo, y ha estudiado tanto las barreras generadas por la disponibilidad y asequibilidad de los servicios de cuidado infantil como por las normas culturales que rodean la maternidad. Este trabajo pretende resaltar otros factores explicativos del Efecto Mateo desde una perspectiva de política pública, más allá de las barreras económicas que limitan el acceso a los servicios formales de cuidado infantil. A través de 34 entrevistas a madres que tienen hijos de entre uno y tres años y que asisten a guarderías públicas y privadas de la ciudad de Barcelona, examinamos las características de los servicios de atención infantil regulados y los factores objetivos del día a día de esas madres para comprender los procesos de toma de decisiones que concurren en la elección del cuidado infantil para los menores de tres años. Los resultados indican que la tarifación social ha permitido el acceso de madres con escasos recursos a las escuelas infantiles públicas, mientras que la calidad de los servicios ofrecidos ha servido para atraer a las clases media y alta. Sin embargo, los servicios de atención a la primera infancia no se han adaptado a las necesidades de las madres de clase trabajadora que, sin encontrarse en una situación de vulnerabilidad social, no pueden costear las guarderías privadas por sus elevados costes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As in other educational fields, in preschool education, it is wealthier families that are more likely to use childcare services, while the disadvantaged children who would most benefit from them remain outside the system. Previous research has shown that the use of formal childcare is related to the social position of the family. Families with lower income and educational attainment spend much less on formal childcare services than families with higher educational and economic capital (Van Lancker, 2013). In other words, some early childhood education policies are found to benefit mainly the middle and upper classes (Bonoli & Liechti, 2018), instead of serving the most vulnerable population. Research has tried to explain this effect, known as Mathew Effect, and has studied both the constraints in the availability and affordability of childcare services, and the cultural norms regarding motherhood (Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018). However, we still fail to clearly understand why mothers from more vulnerable backgrounds are less likely to externalise their children’s care, especially when neither their motherhood culture nor any economic barriers explain this decision.

By carrying out an analysis of the practices and discourses around public and private childcare services, our purpose is to understand how families’ circumstances, mainly factors of social class, work status and family support, are related to the Mathew Effect, beyond any economic barriers.

In recent years, local governments in Catalonia (who run most of the state nurseries) have opted for a model based on offering more public places to complement the existing private supply. It is a model of coexistence between the public network and the private one. Education for the under-threes in Catalonia is neither universal nor compulsory, but in recent years there has been a significant increase in the number of children in the 0–3 age group who attend early years education. The schooling rate has increased from 31.1% in 1998 to 39.7% in 2022.

Since 2017, a sliding scale has been applied to public nursery school fees in Barcelona and many other Catalan cities, with the aim of breaking down financial barriers to accessing them. However, families from all social backgrounds still do not access public ECEC services as much as other groups. The literature has clearly identified availability and affordability as the two principal factors preventing low-income families from accessing early years education, but the evidence observed in Catalonia makes it necessary to look for other factors.

We begin our article by collecting evidence of the positive impact made by nursery education, both as a policy to allow parents to work and also as an instrument for reducing educational inequalities. Second, we address the factors that affect decisions regarding childcare and that condition women leaving or staying in the labour market after the birth of their first child. The subsequent section provides information about the context in which the research took place and methodology used. Then, we present the results obtained on the justifications offered by mothers with children under three years of age for putting them in childcare, and the conditions that shape their choice of state or private nurseries. The final section examines our findings and discusses some of their political implications.

Theoretical Framework

Early Years Education as a Public Policy Instrument

The research that has been carried out in the field identifies three important axes of relevance for ECEC services: first, 0–3 education as a work-life balance policy; secondly, 0–3 education as an educational policy; and, finally, 0–3 education as a policy for redressing educational inequalities.

Early Years Education for the Under-Threes as a Work-Life Balance Policy

Women joining the labour market, together with a lack of co-responsibility in the distribution of domestic and family work, means that children have to be cared for outside the home, generating a demand for effective work-life balance policies and, consequently, a progressive increase in the coverage of childcare services (Sánchez & Villena, 2018). In this sense, childcare services favour a greater incorporation of mothers into the labour market, thus increasing the economic income of the families using these services. (Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018).

Several different studies show that, in the first few years after the birth of a child, the availability of care services for children from zero to three years of age is one of the relevant factors in families’ decisions to return to work, especially in the case of mothers (Baizán & González, 2007; Carta & Rizzica, 2018; Musatti & Picchio, 2010; Nollenberger & Rodríguez-Planas, 2015). The national and international assessments available show positive results for labour market participation when options for early years education exist (Gelbach, 2002; Berlinski & Galiani, 2007, Nollenberger & Rodríguez-Planas, 2011; Schlosser, 2011; Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018). It should be noted, however, that in recent years the provision of nursery places seems to have a less pronounced effect on the participation of mothers in the labour market, probably because the pool of mothers who might react to this incentive is shrinking (Blasco, 2019).

Early Years Education as a Key Educational Stage

The goal of nursery schools is to stimulate children’s development, including both socialisation processes and the acquisition of knowledge, with the aim of increasing their chances of academic success in later educational stages. Although some studies have also identified certain negative effects (Sarasa, 2012; Waldfogel, 2006, Magnuson et al., 2004), most existing assessments of the impact of early childhood education agree that it has a positive impact on children’s development (language, literacy, mathematics, social and emotional development etc.) (Cebolla-Boado et al, 2014; EEF, 2018; Hansen & Hawkes, 2009, Heckman et al., 2012; Schutz et al. 2008; Shutz, 2009, Yoshikawa et al., 2013). This is especially important in the case of children from more disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, since attending preschool education can compensate for initial educational inequalities (Bassok, 2010; Esping-Andersen et al., 2002; Felfe & Lalive, 2012; Ghosh, 2019; McCartney et al., 2007; Tedesco, 2006). At the other end, ECEC is especially valued by middle-class families as a tool to guarantee a progressive transition from the home into compulsory education (Alam, 2020).

Decision-Making Processes Within the Family

An important part of the research on early years education has focused on understanding the decision-making processes that lead some families to use formal care services, while others opt for one of the parents (usually the mother) leaving the workplace, or delegate care of the child to other family members, mainly grandparents (Dowswell & Hewison, 1992; Wheelock & Jones, 2002). These decisions, which in many cases are determined by work-life balance constraints, have been addressed in a generic way through consumption models, in which families look for childcare services on the market according to their preferences and limitations (Alam, 2020; Chaudry et al, 2010). Thus, household income and price of services act as budgetary constraints, analysed in conjunction with the economic gains derived from the mothers working. The cost of care services acts as a weighting factor in decision-making, one that is especially relevant in terms of the mother staying in the labour market or leaving it (Blau & Robins, 1988; Connely, 1992; Ribar, 1995; Del Boca & Vuri, 2007; Tekin, 2007; Van Gameren & Ooms, 2009; Borra, 2010). In terms of the services offered, some of the research has highlighted how the quality of the care services available is also a determining factor in the decision to outsource care or not (Alam, 2020). Factors such as group sizes, educator/child ratios or provider experience are elements that families consider carefully before making a decision (Blau & Hagi, 1998). Third, the research has also identified the existence of a nursery close to the home as an element that favours early years education (Baizán & González, 2007; Borra, 2010; Borra & Palma, 2009; McLean et al, 2017; Suárez, 2013,). Fourth, the educational level of mothers has an observable impact, with families with higher levels of education being more willing to choose formal services (Del Boca & Vuri, 2007; Ghosh, 2019; Mamolo et al, 2011).

Finally, there are important cultural aspects to consider. The entire notion of how children should be brought up, as well as ideas behind what makes a good mother, are often at the root of not using early years education (McLean et al, 2017). Certain social groups (ethnic minorities such as Roma communities or immigrant groups with strong family cultures such as Arabic or Latin American groups) identify the family and the community as the main educational agents for a child, often expressing a certain distrust of schools as childcare services. They highlight the protection and affection of the family, contrasting it with school experiences that are seen as cold and rather impersonal (Botella Gallego, 2015; Crespo et al, 2004; Pastor, 2009).

Although these general limitations have been well documented in the academic policy literature, little attention has been paid to the micro challenges faced by families in accessing childcare places (McLean, Naumann & Koslowski, 2017). And even when these challenges have been addressed (McLean et al., 2017; Skinner, 2005, Jain et al. 2011), the social characteristics of families have not been included in these analyses.

By understanding the practices and discourses around public childcare services, we aim to identify the impact of early education policies on the early childhood opportunities of different types of families. Our efforts focus on observing the degree of congruence between public early childhood care policies (mainly structured around the supply of state nursery school places) and the barriers to accessing these formal care services.

Moreover, all these elements have mainly been analysed in studies that try to understand the decisions made by mothers about staying in the labour market or not. In our study, however, we address the weight of these conditioning factors on the decisions made about what type of formal care service to use, as well as other factors that have been addressed less frequently in the literature.

Research Questions and Research Design

Study Context

At the end of the 1990s, in response to public demand, early childhood education for the under-threes became a political priority, with the Catalan Government pledging the creation of 30,000 state nursery school places. However, it was not until 2004 that a renewed commitment to create these places was announced and a framework for doing so was set up. The ECEC model implemented in Catalonia emulates the primary educational system, designed for students from 3 to 12 years old. Although not being a universal educational stage, access to state nurseries is regulated by the same prioritisation criteria than primary schools. Moreover, state nurseries follow the same opening hours and calendars (Christmas, Easter and summer holidays) established for compulsory education.

Although the law aimed to make educational opportunities more equitable, the distribution of places did not actually prioritise socially disadvantaged areas. To promote low-income families enrolling their children in early childhood education, Barcelona and many other cities in Catalonia have moved from a fixed-fee system to one with sliding-scale fees, with state nurseries fees based on family income information (Blasco, 2018).

Research Questions

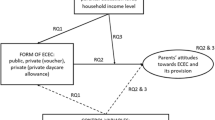

This research seeks to analyse the arguments used by mothers with children between one and three years of age to justify early years education in a state or private nursery school, to identify the factors that condition their choices according to their social positions (level of studies), work status (employment and flexibility) and families (support networks).

The questions that guide this research are:

-

1.

How do families with different social and working status perceive public and private childcare services?

-

2.

How do these families justify their decisions to use public or private childcare services?

-

3.

What characteristics of public childcare services act as barriers for early schooling among vulnerable families?

Method

Information was collected through thirty-four in-depth interviews (Quivy & Campenhoudt, 1993) with mothersFootnote 1 who have children between one and three years of age enrolled in state nursery schools and private nurseries in the city of Barcelona. To the extent that the perspective is a qualitative one, the sample selection does not follow any statistically significant criteria, but reflects a theoretical sampling (Ruiz Olabuénaga, 1996), with the aim of including various sociological profiles. They have been selected to form a heterogeneous sample according to their levels of studies, work status and social class.Footnote 2 Mothers were selected through state and private nurseries located in three different socioeconomic neighbourhoods. Nursery staff were told about the sample stratification in order to find these diverse profiles. As for ethics considerations, participants were informed about the purposes of the research study, and they confirmed that they wanted to be part of it.Footnote 3

Table displaying the work and education status of the sample

Type of service | Work status | Social class | Level of studies |

|---|---|---|---|

State nursery school | Shortened workday | Middle class | Higher vocational studies |

Higher education | |||

In full-time work | Middle class | Vocational studies | |

Working class | Higher education | ||

In part-time work | Lower working class | Primary education | |

Higher education | |||

Out of work | Lower working class | Primary education | |

Lower middle class | Higher education | ||

Private nursery school | Shortened workday | Middle class | Higher vocational studies |

Higher education | |||

In full-time work | Middle class | Higher education | |

Lower middle class | Higher education | ||

Vocational studies |

Following the methodological proposal of Raymond Quivy and Luc Van Campenhoudt (1993), this qualitative approach was complemented by nine exploratory and contextual interviews that make it possible to understand the different organisational structures of the services on offer and the educational approaches and social profiles of the families using this regulated childcare model. The experts interviewed in this exploratory phase are managers of the network of state nursery schools in Barcelona, representatives of private nursery schools’ sector, stakeholders responsible for developing and implementing the legal framework of the public nursery school network in Catalonia and principals of public and private nursery schools. The analysis combines both thematic and structural approaches. The analysis carried out was aimed at making sense of the information gathered during the fieldwork. Content analysis involves compiling the most relevant concepts and thematic areas raised in our conceptual framework, locating certain contents and discourses, and correlating them with the social positions of the individuals analysed.

Results: A Decision Taken in a Two-Step Process

We were intrigued to know the reasons for mothers from different social backgrounds opting for private and state childhood care services or not. Our results show that the decision is taken through a two-step process: first, families decide between taking care of a child at home or outsourcing this care and, second, they choose between different ECEC services.

The First Decision: Outsourcing Childcare, When the Work-Life Balance Logic Meets the Socialising Logic

The discourses of mothers who opt to outsource childcare to state or private nursery schools include the dual objectives of the care of children under three: both as an instrument for improving the work-life balance and a tool for providing educational value. The mothers interviewed had a wide variety of reasons for opting to send their children to nurseries. The need to both work and look after their children appears to be the most important justification given by working mothers for opting for early years education. Our content analysis determined that this work dimension encompasses two main justifications: the need to hold down a job to ensure an adequate family income and/or wanting to keep the same job in order not to lose ground regarding their career paths.

Going back to work. Well, I could have taken leave of absence or whatever, but it’s a matter of how much money we have coming in... both of us need to go out to work.

State nursery / Middle Class / Higher vocational training / Shortened working day

Financially speaking, we can't afford to take leave of absence. At home, I'm the main breadwinner. And my partner has had long spells without work and his job is far less stable. Private nursery / Higher education / Full time.

This justification based on the work-life balance logic was also given by mothers who work sporadically and by unemployed mothers. For these women, early years education responds to the need to have time to look for work or ensures that childcare will be available upon their possible future return to the labour market.

We decided to send him to nursery school for economic reasons. If my husband earned more or if the rents here were lower, I would still be at home with my child, I wouldn't have put him into a nursery. But, of course, if you do the maths, it's just not enough to live on. The idea of putting him into nursery school is so that I can look for a job.

State nursery / Higher education / Out of work

In the case of foreign mothers, leaving the world of work also causes risks for renewing residence permits. In addition to fulfilling their financial needs, these mothers need to be in employment as a requirement for legal residence, which is experienced as an added pressure.

I need time to look for work. My permit is at the 5-year limit. I need a contract to get my documents back in order (…) Everything is very expensive. I don't want to steal or anything. I want to work. When I leave the children at the nursery, I can work until 5pm.

State nursery / Migrant mother / Basic studies / Out of work

In some cases, in outsourcing care to nurseries, the interviewees have foregone their initial preferences. Although they have put their children in nurseries, these mothers would prefer a more autonomous and hands-on parenting model if their personal and family situations were compatible with it. The variables of the mothers who identify with this discourse show us that they are mainly middle-class mothers who have finished higher education, with mid to low incomes or little job flexibility.

I'd already taken leave and we really couldn't afford it. I wish I could be there more time. I'd love to be on leave now, but I can't.

State Nursery / Higher education / Shortened workday

The second major reason for mothers opting for regulated childcare is based on the socialising potential of early education. In this case, given the need to go to work and find childcare, the reasoning behind the choice of a nursery school is based on the educational and socialising value of regulated early years education. Part of what the interviewees say is based on the faith they place in how well-trained are the professional educators who work in the nurseries; they consider them more skilled at teaching the children the acquisition of positive habits and routines than non-professionals. Mothers of two-year-olds who already have the transition to school in mind mention this aspect particularly often in the interviews.

I had already decided that the children needed to go to nursery when they were two. I wanted him to pick up good habits, eating routines, sleeping routines... I was sure about that.

State Nursery / Higher education / Shortened workday

I was sure that whether I worked or not, I wanted her to go to nursery. Why? Because I don't have the same ability, the same patience, the same teaching ability as teachers have. I don't have the same training.

State Nursery / Basic studies / Out of work

To a lesser extent, we can observe an incipient discourse emerging that vindicates personal autonomy. These mothers show a desire to send their children to school—in some cases part-time—so that they can enjoy their own personal space and have more time for themselves. These mothers, who are mainly middle-class and have shortened working hours or are on leave, complement autonomous or family parenting with the part-time use of regulated childcare in order to be able to spend time in training or self-care activities that they do not want to give up.

In short, outsourcing childcare for children under three years of age responds mainly to the need to go out to work, either to do a job that the mother already holds, or in anticipation of going back into the world of work in the immediate future. The educational and socialising role of the 0–3 stage gains more importance when the child is two to three years old, as a preparation for the transition to preschool. Here, the interviewees prioritise a child’s acquisition of everyday habits and knowledge and have faith in the skills of early years educators. Finally, in a few cases, early years education responds to the desire of mothers to gain some personal time, in addition to the reasons regarding work-life balance and socialisation which have already been discussed.

Our results show that the mothers who opt to outsource care to state nursery schools and those who use private nursery schools give very similar justifications for their choices, with the exception of two types of justifications, mainly voiced by users of the public network. These are, on the one hand, unemployed mothers who opt for early years education in preparation for their possible future entry into the labour market. And on the other hand, mothers who state that they use nurseries to have more time and personal space for themselves. These are two markedly different profiles. Among the first are mothers with low education levels and unstable working statuses, for whom only the low sliding-scale rates in public schools are affordable, and who could not even contemplate paying for early years education in the private network. The latter are mainly mothers with university degrees and job flexibility who make subsidiary use of state nursery schools. For this profile, it is also the sliding-scale pricing that allows them to choose an affordable option that fits with their economic situation while they are not working; at the same time, this justification is complemented with a commitment to the quality that the nursery school offers compared to other options such as babysitters or the family network.

The Second Decision: Outsourcing, But Where?

Early years education practices vary significantly depending on the characteristics of the different services offered by the public and private sectors and how these fit the needs of different families. Understanding the existing logics behind these approaches allows us to recognise the limits and potential of these two early years care options.

The state-run network of nursery schools in Barcelona follows strict codes in terms of the quality of services and facilities on offer. The network demonstrates a clear commitment to quality education and innovative teaching. This has shaped the development of facilities with large, open and welcoming spaces with considerable investment in educational equipment. While the educator/child ratios are the same as in private nurseries, it is more common to find support or complementary staff in state nurseries, which does in fact mean a difference in human resources between the types of nurseries. However, as stated above, the morphology of the state nurseries emulates primary schools’ organisation and presents a school calendar and timetable that is difficult to fit into the family logistics of many families. In the private network, on the other hand, the prioritisation of the work-life balance function translates into longer opening times every day and more days open per year. Fees are on a sliding scale in the case of the public network while in the case of private nurseries they are fixed. The public network implies a markedly lower cost for households in the lower-income brackets, while the differences are lessened for middle and high incomes.

There are significant differences between early years education in state nurseries and in private ones. So, what are the factors that lead families to choose one over the other? Families who opt for state nursery schools do so based on one (or more) of these three factors: the quality of the services provided, affordability and their commitment to state education. State nursery schools are widely considered as being a high-quality option. This good reputation earned by state nursery schools is an important factor in making them attractive.

State nursery projects are very similar wherever you go. I generally like them a lot more than the private ones. Usually, the space itself is beautiful, with many different areas, with a Montessori-based philosophy... I hadn't heard good things about the private ones in the neighbourhood. They were the last resort if we didn’t find something else. State nursery / Higher education / Shortened workday.

Second, the act of opting for a state nursery is often presented in terms of ideological commitment, especially in the case of families that have greater cultural and economic capital. These types of families want to make a firm commitment to state education even at this early stage where degrees of coverage or implications in terms of public policy or ideological tensions are not comparable to primary education. I want to stand up for the state system (...) Yes, I want my child to go to a state primary school, if possible, and secondary as well. State nursery / Higher education / Shortened workday.

In contrast, families with lower incomes mention the higher prices of private nurseries more often. This makes them less attractive than the more affordable state nursery schools under the current model of sliding-scale pricing. Thus, families with lower incomes point to the low fees as a key factor in opting for 0–3 early years education. The new state nursery pricing system based on sliding-scale pricing has fostered early years education for children from lower-income families, which has led to a progressive change in the make-up of the families that use the state network of nursery schools, which had traditionally been occupied by the middle classes. This new pricing model has meant that lower-income families, who in many cases could not afford to access state or private nursery school services, now have the option of breaking down the economic barriers that were preventing them from accessing 0–3 early years education.

Of the mothers interviewed who opt for private nurseries, some raise the difficulties of accessing the state nursery school system due to a lack of places available. They give this as an explanation for choosing early years education in a private nursery.

In fact, we applied to the state nursery that is closest to us, but the woman there told us that we should look for another nursery because we had very few chances.

Private nursery / Vocational education / Full time.

Of the families whose children attend private nurseries, there is also a group that did not contemplate early years education in the state network at all. These are families where both parents work full time and need a service which provides longer daily school hours and a more flexible yearly schedule, especially during the Christmas and Easter holidays. These families do not even consider state nurseries for their children, despite them having a reputation for higher quality, better facilities or lower fees, because the type of service offered does not match their needs. These families have mothers with higher workloads who cannot afford a reduction in working hours or cannot opt for flexible working hours. They require full-time early years education and, in many cases, the use of before-school clubs or after-school services which are offered more commonly by the private system.

First problem, what do we do in July? Because the holidays are longer in state nurseries and schools. Here they don't close for the Christmas holidays. We work. That was already a handicap. What do we do with the child?

Private nursery / Higher education / Full time

I already have a very busy schedule, very condensed so I can pick them up if one day for whatever reason I can't come, I know that it's fine, here I have an hour and a half extra just in case (...)

Private nursery / Higher education / Full time

It should be noted that formal early years education often needs to be used in conjunction with other care strategies. The complementary services offered by both state and private nurseries—before-school clubs and/or after-school services—offer more flexibility to families and can be adapted to their logistical and work needs. In state nursery schools, mothers that work full time refer more frequently to the existence of a certain degree of work flexibility, which is especially necessary for cases in which the child is ill since the regulations about children not attending when they are ill are applied more rigidly by the state nurseries than by the private nurseries. In other cases, the limited time available to parents is complemented by a family network, especially grandparents (both maternal and paternal). This network is especially important when faced with the public system’s more limited hours and many days closed for holidays. Finally, some families combine the use of a state nursery school with hiring a babysitter to look after the children when they cannot be cared for by their parents.

So, my parents used to come to our house at around 7:20-7:30 in the morning (...) I don't know what I would have done without my parents. I used to leave for work at 7:30. My husband leaves at the same time as me. I arrive a bit after 5 PM. He arrives later. Then, once I arrived, they stopped being babysitters, and became grandparents.

Private nursery / Vocational education / Shortened workday

In short, price appears as a factor in the choice of care only in the case of families with lower incomes and less need for longer hours who see state nursery schools as an affordable option for early childhood care. In the case of families with longer working hours, it is only having flexible jobs or a family support network that allows them to be able to choose state nurseries. For families with long working hours and with no possibility of opting for flexible working hours and/or family support, the choice is limited to the only service that covers their working needs: private nurseries. Thus, it is each family unit’s objective situation, especially that of the mothers in each family, that allows us to understand and explain this heterogeneity in work and parenting practices.

Discussion

Based on our qualitative interviews, we are able to identify three groups of mothers who are located on different points of the social status spectrum and facing different combinations of working conditions and available family support. All of them manage to find 0–3 early years education care solutions, but early childhood policies have not answered the challenges of one of these groups.

Firstly, we have a group of mothers with high social status: they have high levels of education, job stability, economic resources, solid social networks, etc. They have stable work situations and have a certain flexibility in their work and/or have family support networks. They use state nursery schools mainly for socialisation and learning reasons, although using them also plays an important part in them being able to go out to work easily. These are mostly women with either mid-level (vocational training), or high-level educational status (university studies), and some degree of economic stability and job flexibility (they often work part-time) or family support networks. The enhanced work-life balance derived from these last two elements makes the role of education in their choice relatively more important: they see early years education as a strategy for enhancing the skills and sociability of their children. Many of these mothers have very stable jobs, e.g. in the public administration, or in in public or multinational companies, which all have very family-friendly regulations. If they have been able to shorten their working hours, these mothers either have their children spend less time at nursery, or take advantage of those hours for household chores, training or self-care. A quest for personal autonomy is also something sought by some of the mothers in this group, which includes women with high educational profiles and who have chosen to leave the labour market to raise their children at home. They use low-intensity early years education in the public network to have some personal time.

The second group is made up of mothers who, for economic reasons or for their working conditions (a risk of losing their jobs outright or losing their current positions and thus hindering their career paths), work full time with little or no flexibility and who opt for private nurseries, a choice justified mainly by the demands of their jobs. Here, mothers with high educational profiles are grouped together with working-class families which have very different working conditions. Despite the wide diversity of nurseries that exist in the city, in terms of spaces, educational projects and prices, all the families in this second group have opted for private nurseries that have longer hours and shorter holidays, since they often have no family support.

Finally, there is third group, which is made up of mothers who have low educational capital and greater social vulnerability and who use state nursery schools. These women are mostly migrants and have little social capital. They have diverse work situations: some work in the underground economy (domestic service, hospitality…), others are unemployed and busy seeking work. Most of these women have been referred to the state nurseries from social services, either so that their children can have the possibility of socialising and getting ready for preschool, or to allow the mothers to juggle their very precarious jobs and/or acquire skills in training courses. In these cases, it is the sliding-scale pricing of the state nurseries that allows them to access a service that would be inaccessible at market prices.

Studying mothers’ positional characteristics (education levels and income) has helped improve our understanding behind their decision-making about staying in the labour market, which has been seen in previous research ((Del Boca & Vuri, 2007; Ghosh, 2019; Mamolo et al, 2011). Our research shows that these decisions are not just affected by these positional conditions but also by the interaction between these positional characteristics, labour conditions and the supply-side structure in childcare provision.

Making more places available in state nurseries has led to more families being able to access early years education, especially families who have traditionally been excluded from the private market. However, our results point out that supply-side structure cannot be reduced to the number of places (as literature has traditionally done, see Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018) but also the service morphology affects the attraction of different family profiles to ECEC services. Our analysis points out three important limitations to public ECEC policy in Catalonia, that can be applicable to other contexts where public nurseries have become the key policy for the under-threes.

First, public ECEC services have emulated the design and coverage (in terms of opening hours, holidays and access criteria) of state primary schools, making them less flexible and, thus, less useful as work–family balance tools. The private network, on the other hand, offers greater time flexibility and a wider-reaching service, making it the only feasible option for certain families. In this sense, the current ECEC policy does not answer the needs expressed by those families with long working days or less flexible labour conditions. For these families, the private services become the only option for formal care but it must be taken into consideration that families with fewer resources are neither able to opt for state schools because of the lack of flexibility nor the private ones because of the cost. This situation can be understood as a lack of availability, what force these families to relegate care to family networks or, in the most extreme cases, causing them to leave the labour market, as Baizán and González (2007), Carta and Rizzica, (2018), Musatti and Picchio (2010) or Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas (2015) have previously identified for other contexts.

Secondly, sliding-scale pricing in Barcelona has led to a reduction in economic barriers for accessing 0–3 early years education. However, this has not been matched by establishing access criteria that prioritise helping lower-income mothers solve their work-life balance needs and compensate for their children’s educational disadvantages (beyond referrals from social services). Thus, the lack of public places and the lack of prioritisation criteria have led to the nurseries being used by many different profiles of families and offer limited options for mothers who cannot afford places in private nurseries. Data published by the Barcelona Institute of Regional and Metropolitan Studies indicate a slight change in the social profile of families in states nurseries since the introduction of these progressive schooling fees. Between the 2017 and the 2020, the percentage of families from the lowest social decile has only increased by 3%. Remaining economic barriers and cultural factors, identified by previous research, can explain the limitations observed in increasing preschool enrolment among vulnerable families.

Thirdly, the use of public nurseries is in most cases conditioned by the availability of informal support or flexible working conditions to complement it. Having access to a public nursery is not enough to answer childcare needs, and in these cases, using the private sector supply or leaving labour markets altogether appear to be the most common options. In line with previous qualitative research (Larsen, 2004; Skinner, 2005), we have found that a combination of formal and informal care tends to be the most common strategy adopted by families in different countries. Some mothers opt for regulated early years education combined with a reduction in working hours. Other work in companies where work-life balance is facilitated through flexible working hours. And in other cases, mothers are forced to plan family logistics painstakingly and combine multiple resources in order to balance their workday with childcare. Our research adds value to these findings, highlighting the limitations of public childcare policy.

These three limitations show how important it is to reformulate the role of state nursery schools, both as an educational policy and also as a mechanism aimed at guaranteeing equality and employment inclusion for all women. In an attempt to solve the Mathew Effect, Catalan education policy has focused on reducing economic barriers and increasing the number of places for the under-threes. Sliding-scale pricing has allowed low-income families to access state nursery schools, and the quality of services has served to attract the middle and upper classes. However, one topic that has not yet being addressed is the adaptation of early childhood care services to respond to the needs of working-class mothers who, although not being in a situation of extreme social vulnerability, cannot afford either private nurseries—which are those that provide the most extensive services—or use public ECEC services—which do not fit their needs.

Conclusions

Our results show a certain polarisation of the public present in state nurseries. On the one hand, children from the most vulnerable families, mostly derived from social services, are observed. On the other hand, children from middle-class families, who have more resources and enjoy more flexible working conditions, are observed. Mathew Effect is now visible in those family profiles that are located in the gap between these two extremes.

This situation limits the redistributive impact of ECEC policies in Catalonia. Paradoxically, the debate now is not about engaging absent publics, but about reducing even more the economic barriers to access. Our conclusion predicts the failure of this policy to reduce the Mathew Effect, as long as our evidence identifies new reasons for this effect beyond price barriers. It is essential to consider reformulating the state nursery schools model, offering more flexible and extensive services in order to answer to a plethora of highly diverse situations. Otherwise, working-class families will not feel that state nurseries are also for them.

Notes

Decisions on childcare are frequently taken by all members of the family together. However, this study focuses on what mothers say, because data shows that main changes in work trajectories after childbirth affect them more. In Spain, 4.3% of women between 20 and 45 years old cut down their working hours to take care of their children, while only 0.17% of men do the same (EPA 20222 T).

The classification in each social class obeys the structure of the capitals owned by the individuals. The combination of education level, employment status, income level and place of birth makes it possible to locate the different individuals studied within the coordinates of the social structure. This combination allows us to make the social positions of the interviewees much more detailed. For this reason, our typological sample categorizes individuals with higher education, but with a fragile or precarious labour and economic position —part-time work, informal work or unemployment—as lower working class.

The interview outline was supervised and accepted by the Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

References

Alam, M. J. (2020). Who chooses school? Understanding parental aspirations for child transition from home to early childhood education (ECE) Institutions in Bangladesh. In: Tatalović Vorkapić, S., & LoCasale-Crouch, J. (Eds.), Supporting Children's Well-Being During Early Childhood Transition to School (pp. 85–107). IGI Global. ISBN13: 9781799844358.

Baizán, P. & González, M.J. (2007). ¿Las escuelas infantiles son la solución? El efecto de la disponibilidad de escuelas infantiles (0–3 años) en el comportamiento laboral femenino. In: V. Navarro (ed.) Situación Social de España, Vol. II, Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

Bassok, D. (2010). Do Black and Hispanic children benefit more from preschool? Understanding differences in preschool effects across racial groups. Child Development, 81(6), 1828–1845.

Berlinski, S., & Galiani, S. (2007). The effect of a large expansion of pre-primary school facilities on preschool attendance and maternal employment. Labour Economics, 14(3), 665–680.

Blasco, J. (2018). De l’escola bressol a les polítiques de primera infància: l’educació i cura de la primera infància a Catalunya. Col·lecció Informes Breus, Núm. 66. Barcelona: Fundació Jaume Bofill.

Blasco, J. (2019). "Dimensió social de l’educació en cura en la primera infància", Barcelona: IGOP (Projecte Recercaixa "Edu 0–3").

Blau, D. M., & Hagy, A. P. (1998). The demand for quality in childcare. Journal of Political Economy, 106(1), 104–146.

Blau, D. M., & Robins, P. K. (1988). Childcare costs and family labor supply. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(3), 374–381.

Bonoli, G., & Liechti, F. (2018). Good intentions and Matthew effects: Access biases in participation in active labour market policies. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1401105

Borra, C. (2010). Childcare costs and Spanish mothers’ labour force participation. Hacienda Pública Española/revista De Economía Pública, 194(3), 9–40.

Borra, C., & Palma, L. (2009). Childcare choices in Spain. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 323–338.

Botella Gallego, N. (2015). Mujeres marroquíes: alimentación, identidades y migración. PhD Thesis.

Carta, F., & Rizzica, L. (2018). Early kindergarten, maternal labor supply and children’s outcomes: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Public Economics, 158, 79–102.

Cebolla-Boado, H., Radl, J. i Salazar, L. (2014). Aprenentatge i cicle vital. La desigualtat d’oportunitats des de l’educació preescolar fins a l’edat adulta. Barcelona: Obra Social «La Caixa».

Chaudry, A.; Henly, J. & Meyers, M. (2010). Conceptual frameworks for childcare decision making. White Paper.

Crespo, I.; Lalueza, J.; Portell, M. & Sánchez-Busques, S. (2004). Aprendizaje Interinstitucional, Intercultural e Intergeneracional en una Comunidad Gitana. http://www.5d.org/postnuke/index.php

Del Boca, D., & Vuri, D. (2007). The mismatch between employment and childcare in Italy: The impact of rationing. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 805–832.

Dowswell, T., & Hewison, J. (1992). Mother’s employment and child health care. Journal of Social Policy, 21(3), 375–393.

EEF (2018) The Educational Endowment Foundation Toolkit. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit/early-years-intervention/

Esping-Andersen, G., Gallie, D., Hemerijck, A., & Myles, J. (2002). Why We Need a New Welfare State. Oxford University Press.

Felfe, C. & Lalive, R. (2012). Early Childcare and Child Development: For Whom it Works and Why. In IZA Discussion Paper 7100.

Gelbach, J. B. (2002). Public schooling for young children and maternal labor supply. American Economic Review, 92(1), 307–322.

Ghosh, S. (2019). Inequalities in demand and access to early childhood education in India. IJEC, 51, 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00241-8

Hansen, K., & Hawkes, D. (2009). Early Childcare and Child Development. Journal of Social Policy, 38(2), 211–239.

Heckman, JJ., Pinto, R, Savelyev, P. (2012). Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w18581

Larsen, T. P. (2004). Work and care strategies of european families: Similarities or national differences? Social Policy and Administration, 38(6), 654–677.

Le Bihan, B., & Martin, C. (2004). Atypical working hours: Consequences for childcare arrangements. Social Policy and Administration, 38(6), 565–590.

McCartney, E., Boyle, J., Forbes, J., & O’Hare, A. (2007). «An RCT and economic evaluation of direct versus indirect and individual versus group modes of speech and language therapy for children with primary language impairment. Health Technology Assessment., 11(11), 1–139.

McLean, C, Naumann, I & Koslowski, A .(2017). Access to Childcare in Europe: Parent’s Logistical Challenges in Cross-national Perspective. Social Policy and Administration 51(7), 1367–1385

Mamolo, M., Coppola, L., & Di Cesare, M. (2011). Formal childcare use and household socio-economic profile in France, Italy, Spain and UK. Population Review, 50(1), 170–194.

Musatti, T., & Picchio, M. (2010). Early education in Italy: Research and practice. IJEC, 42, 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-010-0011-9

Nollenberger, N., & Rodriguez-Planas, N. (2011). Childcare, Maternal Employment and Persistence: A Natural Experiment from Spain. IZA Discussion Paper, 4069

Nollenberger, N., & Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2015). Full-time universal childcare in a context of low maternal employment: Quasi-experimental evidence from Spain. Labour Economics, 36, 124–136.

Pardo, M., & Wordroow, C. (2014). Improving the quality of early childhood education in Chile: Tensions between public policy and teacher discourses over the schoolarisation of early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood, 46, 101–115.

Pastor, B. G. (2009). Ser gitano fuera y dentro de la escuela: una etnografía sobre la educación de la infancia gitana en la ciudad de Valencia. CSIC Press.

Pavolini, E., & Van Lancker, W. (2018). The Matthew effect in childcare use: A matter of policies or preferences? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1401108

Quivy, R., & Van Campenhoudt, P. (1993). Manuel de recherche en sciences sociales. Bordas Editions.

Ribar, D. (1992). Childcare and the labor supply of married women: Reduced form evidence. Journal of Human Resources, 27(1), 134–165.

Sánchez, C., & Villena, N. (2018). Conciliació i corresponsabilitat Una perspectiva feminista. Fundació Josep Irla.

Sarasa S. (2012). Efectes de l’escola bressol en el desenvolupament dels adolescent. In Gómez- Granell C. & Marí-Klose P. (Dir), IV Informe sobre la situació de la Infància, l’Adolescència i la Família a Catalunya i Barcelona, CIIMU.

Schlosser, A. (2011). Public preschool and the labor supply of Arab mothers: Evidence from a natural experiment. Working Paper. Tel Aviv University.

Skinner, C. (2005). Coordination points: A hidden factor in reconciling work and family life. Journal of Social Policy, 34, 99–119.

Suárez, M. J. (2013). Working mothers’ decisions on childcare: The case of Spain. Review of Economics of the Household, 11(4), 545–561.

Tedesco, J.C. (2006). Igualtat d’oportunitats i política educativa. In Bonal, X., Essomba, M.A., & Ferrer, F. (Coord.) Política educativa i igualtat d’oportunitats. Editorial Mediterrània.

Tekin, E. (2007). Childcare subsidies, wages, and employment of single mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 42, 453–487.

Yoshikawa H., Weiland C., Brooks-Gunn J,. Burchinal MR., Espinosa LM., Gormley WT, Ludwig J., Magnuson KA., Phillips D. & Zaslow MJ. (2013), Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base on Preschool Education. Foundation for Child Development

Van Gameren, E., & Ooms, I. (2009). Childcare and labor force participation in the Netherlands: The importance of attitudes and opinions. Review of Economics of the Household, 7, 395.

Van Lancker, W. (2013). Putting the child-centred investment strategy to the test: Evidence for the EU27. European Journal of Social Security, 15(1), 4–27.

Waldfogel, J. (2006). What do children need? Public Policy Research, 13, 26–34.

West, A., Blome, A., & Lewis, J. (2020). What characteristics of funding, provision and regulation are associated with effective social investment in ECEC in England, France and Germany? Journal of Social Policy, 49(4), 681–704.

Wheelock, J., & Jones, K. (2002). Grandparents are the next best thing: Informal Childcare for working parents in urban Britain. Journal of Social Policy, 31(3), 441–463.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported by the Recercaixa Programme (2017 edition).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. This material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

González-Motos, S., Saurí Saula, E. State Nurseries are Not for Us: The Limitations of Early Childhood Policies Beyond Price Barriers in Barcelona. IJEC 55, 295–312 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-022-00343-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-022-00343-w